Home | Category: Culture, Science, Animals and Nature / Death and Mummies

EGYPTIAN BOOK OF THE DEAD

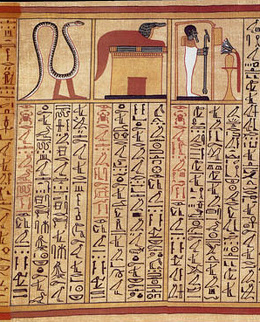

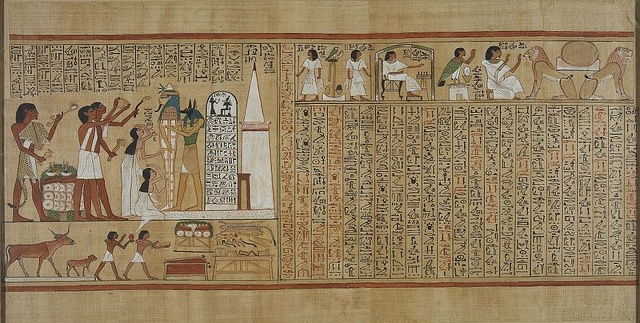

The "Egyptian Book of the Dead" is a modern-day name given to a variety of texts that served a number of purposes, including helping the dead navigate the underworld. Much of the “Book of the Dead” is a compilation of rituals, incantations and spells designed to assist the dead in their journey to the netherworld. Hieroglyphics from this book were usually written all over the walls inside tombs. Egyptian Book of the Dead” did not provide information on what death was like give advise on how to make mummies and prepare tombs.

The Egyptian name of the “Egyptian Book of the Dead” was “Per Em Hru” , which literally translated means “Book of Coming Forth by Day” or “Journey of the Light.” It was created around 1500 B.C., when papyrus became widely used and people could more easily afford to be buried with papyrus rolls rather pay out for expensive tomb paintings or wooden coffins. Many copies of the “ Egyptian Book of the Dead” have been excavated from tombs. Many spells are accompanied by illustrations with scenes of the afterlife.

The “Egyptian Book of the Dead” was never a real book but rather a collection of spells from various sources. In ancient Egyptian times the spells often varied from text to text. Many of the spells originated in the “Pyramid Texts” and the “Amduat”.

See Separate Article: BOOK OF THE DEAD AND OTHER ANCIENT EGYPTIAN RELIGIOUS TEXTS africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Egyptian Book of the Dead (Penguin Classics) by Wallace Budge and John Romer (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day” The Complete Papyrus of Ani Featuring Integrated Text and Full-Color Images, Illustrated, by Dr. Raymond Faulkner (Translator), Ogden Goelet (Translator), Carol Andrews (Preface) (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Egyptian Book of the Dead” by Rita Lucarelli and Martin Andreas Stadler (2023) Amazon.com;

“Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2015) Amazon.com

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

Journey Described in the Egyptians Book of the Dead

The Book of the Dead guided Ancient Egyptians through death and on to the afterlife. John Taylor, the British Museum's expert in these ancient last rites, told The Guardian the best way to think of The Book of the Dead is as a reassuring map to the afterlife. "It is a kind of a combination of a spell, a talisman and a passport, with some travel insurance thrown in too." [Source: Vanessa Thorpe, The Observer, October 24, 2010]

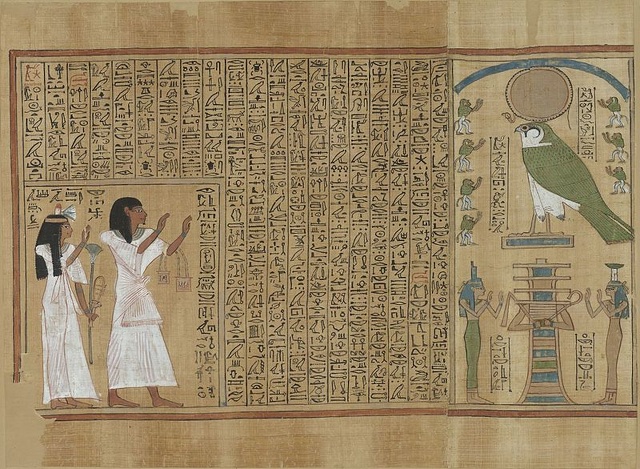

In 2011, the Reading Room at the British Museum showcased, for the first time, the entire length of the Greenfield Papyrus, which, at 37 metres, lays out each detailed stage of the ancient Egyptians journey to the afterlife. Also on display were a succession of paintings taken from the papyri of Hunefer and of Ani, probably the two most famous works to depict the many episodes, or trials, that together constitute The Book of the Dead. The papyri, which were made for well-to-do customers between 1500BC and 100BC (the Hunefer and Ani ones date from 1280-1270BC), each function like an A-to-Z of the netherworld: full of symbols and landmarks that orient and guide the dead soul through a projected ghostly landscape.

Vanessa Thorpe wrote in The Observer, “The script of a papyrus is read from one side across to the other, depending on which way round the depicted animal heads are facing. The spells and incantations appear alongside the images they evoke and they commonly deal with the sort of problems faced in life, such as the warding off of an illness. They are usually rather straightforward: prose rather than poetry. "Get back, you snake!" reads one for protection against poisonous serpents. For the ancient Egyptians, the act of simply writing something down formally, or painting it, was a way of making it true. As a result, there are no images or passages in The Book of the Dead that describe anything unpleasant happening. Setting it down would have made it part of the plan. There was, however, always a heavy emphasis on dropping the names of relevant gods at key points along the journey.[Source: Vanessa Thorpe, The Observer, October 24, 2010]

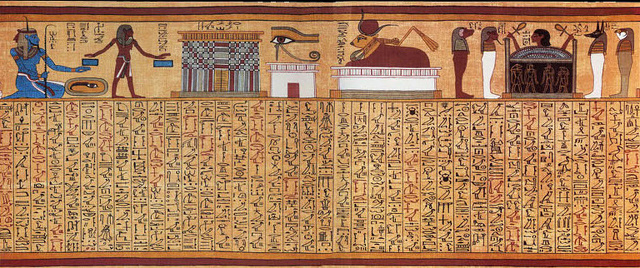

The best-known stage in this journey through the afterlife is the weighing of the heart. Scales watched over by Anubis are used to balance the heart of the dead soul against a feather, which represents truth. If the heart passes the test, then the way forward is clear. If not, the unseen threat is that the Devourer who hovers below will snap up the organ in its crocodile jaws...When it comes to scary monsters, the ancient Egyptian Devourer is always going to be hard to top. With the head of a crocodile, the body of a lion and the hindquarters of a hippo, it is certainly more exotic than the average Halloween outfit. And, though it sounds risible now, for centuries in Egypt the grim fear of meeting this evil, "cut'n'shut" beast on the other side of death helped to shore up an entire system of belief, a system shared by pharaohs and artisans.

Other stages of the journey are just as fascinating, if less perilous. A board game called Senet, which looks a little like a cross between chess and backgammon, is an allegory of the journey to paradise. Depicted elsewhere is the ritual of the opening of the mouth, which involves a series of macabre tools that were often buried inside a tomb with the dead body. At a pivotal moment, the dead soul also has to satisfy the demands of 42 separate judges, saying each one of their names out loud to please them. It makes The X Factor look easy. And this is where the papyrus crib sheet came in. It carefully listed each god in the correct order for the recently deceased client.

Book of the Dead

If all else failed, at the final hurdle there was a handy spell designed to conceal all sins and mistakes from the gods by making them invisible. And then, when a dead soul finally completed the journey, there waiting for them at the end, so the papyri all promised, would be an ancient Egyptian version of Heaven: full of reeds and water and looking very much like the Nile Valley in the year of a good harvest, replete with grain and food and drink.

Spells from the Egyptian Book of the Dead

“ Egyptian Book of the Dead” contained 200 spells and incantations that covered all different aspects of death and the afterlife. Many were designed to thwart specific demons and obstacles on the journey in the afterlife. There were spells for transferring “ ka” (the life force) into statues and ones for restoring limbs and sensory organs snatched by monsters. One spell repels a gruesome crooked-legged scarab. Another transforms the corpse into a crocodile, snake or bird to get past a ram-headed deity. Yet another prevents one from having to consume urine or feces. Some images show the dead turned upside down, throwing the digestive system into reverse so they ate their feces and defecated food. Each spell began with Osiris and the name of the deceased. Osiris’s name was sort of title for the dead.

Spell 148 went: “Book of Secertes for him who is in the netherworld, (for) initiating the blessed [deceased] into the Mind of Re...(it contains) secrets of the Nether World, mysteries [such as] (how) to cleave mountains and penetrate valleys...secrets wholly unknown; (how to preserve the heart of the blessed one: widen his steps, give him his (powers of ) locomotion, do away his deafness, and reveal his face and (that of) the God...This roll is very secret. No one else is ever to know (it); (it is) not to be told (to) anybody. No one is see nor ear to hear (it) except the soul and its teacher.” [Source: Thomas Allen, The “ Book of the Dead” , Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago]

By around 1000 B.C. most of the spells were standardized. But even then they were differences between spells regarded as the same. The wording from text to text was sometimes slightly different. People sometimes changed the wording to meet their individual needs.

Opening of the Mouth

Rituals for the day of burial such as the "Opening of the Mouth" form a prominent part of the Book of the Dead. This rite usually involved a priest touching the face mask of a mummy with a series of implements as he uttered mystical incantations. Rachel Campbell-Johnston wrote in the Times of London,” Like a midwife clearing the orifices of a newborn baby, he symbolically reopened the ears, nose and mouth of the corpse. Several manuscripts depict this re-animating moment. A few also show a gruesome accompanying ritual in which the foreleg is severed from a still living calf and presented still pulsating , along with its freshly excised heart, to the human corpse. In the papyrus of Hunefar the mother cow is shown watching. The spectator can almost hear the wailing echo of her flat-tongued bawl. A symbolic lamentation for a passing soul. “

Thorpe wrote: “1) To perform it on a mummy — Hunefer's, in this case — a priest would touch the face mask with a series of implements, symbolically unstopping the mouths, eyes, ears and nostrils so the corpse regains its faculties. 2) Two women mourning for the dead Hunefer. The standing one is named as his wife, Nasha. 3) The mummy of Hunefer, adorned with a mask. It is held up by a jackal-headed figure representing the god Anubis, protector and embalmer of the dead. This may represent the god himself or a priest wearing a mask to impersonate him. 4) An inscribed tablet, which would have been set up outside Hunefer's tomb. At the top, a scene shows Hunefer worshipping Osiris. 5) A stylised depiction of Hunefer's tomb. [Source: Vanessa Thorpe, The Observer, October 24, 2010]

Book of the Dead Spell 125: the Judgement Procedure

Martin Stadler of Würzburg University wrote: “The vignette of the judgment after death, attested from the mid-18th Dynasty onward, gives us an idea of the actual trial procedures. Although its association with Book of the Dead spell 125 is well known, the vignette is also found in accompaniment to other BD spells associated with the judgment. After the New Kingdom, the representation is found in a variety of contexts—coffins, shabti chests, mummy bandages, shrouds, and in one instance, a relief in the small Ptolemaic temple of Deir el-Medina. Although the set of figures displayed in the judgment scene changes over time, a typical representation comprises the introduction of the deceased to the judgment hall by a deity (Anubis, Thoth, Maat, or the Goddess of the West); a scale on which the deceased’s heart is weighed against a feather (the symbol of maat: cosmic order and justice); a devourer (a beast that is part lion, part crocodile, and part hippopotamus), who stands by, ready to eat the heart of—and thereby annihilate—the sinful deceased; Thoth, who records the result in writing; and the enthroned Osiris, presiding as chief judge. All or some of a group of 42 judges are also shown. Abbreviated versions of the vignette exist, as well as more elaborate depictions. [Source: Martin Stadler, Würzburg University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“According to its title, BD spell 125 is to be recited by the deceased when entering the judgment hall. It is intended to ensure that the individual will pass through the judgment phase and be found ethically worthy to enter the realm of Osiris. To this end, the deceased claims to know the names of the judges and asserts his purity. As the knowledge he displays reveals familiarity with cults, rituals, and cult topography, it presents him as one who is versed in religious matters. In the spell’s main section, the deceased addresses each of the 42 judges by his name and cult center. Each address is followed by the deceased’s denial of having committed a specific sin, hence the term “negative confession.” The 42 negative confessions confirm the speaker’s equanimity—that is, they confirm that his behavior did not undermine or disturb the societal peace (for example, through theft, adultery, murder, or adding to the balance) and that he acted according to the cultic prescriptions, such as that of respecting the cultic chastity. Together with Egyptian instructions that parallel BD spell 125, and autobiographical texts that commemorate the achievements of individuals of the Egyptian elite, the negative confession is a major source of ancient Egyptian ethical standards. A life lived in accordance with these standards was a life lived according to maat. Over the more than 1500 years of the spell’s tradition, the set of negative confessions remained remarkably stable, varying from (BD) manuscript to manuscript only in sequence. Variations are particularly noticeable between the redactions of the New Kingdom, Third Intermediate Period, and Late Period, where it is apparent, at least in some cases, that scribes had re- or misinterpreted words or phrases when copying.

“Some scholars have suggested that BD spell 125 is an adaptation of the oaths of purity sworn by priests during their initiations. This suggestion is prompted by the texts of two priestly oaths whose structure and content are reminiscent of the negative confession of BD 125. The oaths, however, are written in Greek on papyri of Roman date. It has been argued that the recent discovery that the oaths are in fact translations from Egyptian constitutes further support for the suggestion. The oaths’ Egyptian version is contained in the so-called Book of the Temple, a manual on the ideal Egyptian temple. However, there are no known manuscripts of The Book of the Temple that predate the Roman Period. Therefore, the text might be much younger than the first witnesses of BD spell 125, although a Middle Kingdom date for the Egyptian priestly oaths has been advocated on the basis of The Book of the Temple’s Middle Egyptian grammar. This dating method has not been unanimously accepted by Egyptologists; thus it cannot be definitely excluded that there is a reverse dependence, i.e., that the priestly oaths are, in fact, adaptations of BD spell 125. The known and available Egyptian sources do not presently allow a decisive conclusion, but it can be stated that there is a relationship between ritual texts pertaining to the temple context and texts that were used for funerary rituals, or as mortuary compositions.”

Ideas About Death in the Egyptian Book of the Dead

The point of the whole experience for the moribund traveller was a vital reunion with their dead ancestors. "The family unit was crucial," Taylor told the Observer. "You cared for your dead family because they were still there, on the other side. They could communicate with you and had power over you. So people wrote letters to the dead asking things like, 'Why are you still punishing me?'" Death, he said, was a familiar part of daily life and ancient Egyptians felt closely connected to it, if not quite comfortable with it. Most people died before they were 40 and so mapping out a plan for the afterlife was a way to handle this unpalatable probability. [Source: Vanessa Thorpe, The Observer, October 24, 2010]

Vanessa Thorpe wrote in The Observer, “Intriguingly, evidence reveals that there were some sceptics who were prepared to question the likelihood of a paradisal "field of reeds" waiting for everyone on the other side of death. Taylor confirms that documents have been found in which these sceptics, the Richard Dawkins of their day, seem to query the point of The Book of the Dead. Most, however, seem to have decided that buying a papyrus was a useful insurance policy in case it all turned out to be true.

Among all the varied ideas contained in The Book of the Dead manuscripts there is no sense anywhere that the scribes were setting down history for posterity. Neither is there, Taylor says, any striving for objectivity in the way sentiments are expressed. Instead, the papyri are a practical piece of political and spiritual spinning, a means to an end delivered at an agreed price.

And yet because these papyri deal with fear and death and hope, they cannot help but provide an immensely absorbing window into the minds and emotions of an ancient society. Their images and hieroglyphs, known to every schoolchild, have now become the emblem of all that is mysterious to us about this remote culture. Yet the study of the complex transformation the ancient Egyptians hoped they would undergo in death is oddly humanising. In their imaginative scheme to defeat mortality and to be reunited with lost members of their family, they are somehow almost recognisable.

Much of the ancient Egyptian art that has made it to us today was oriented towards death, the dead and the quest for the afterlife. The Egyptians believed that artistic renderings of images placed in tombs would become real and accompany the deceased to the afterlife. Some scholars say the Egyptian belief in the afterlife is what helped ancient Egypt survive even after the empire had died.

Book of the Dead Field of Reeds

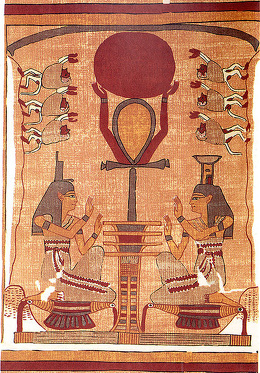

Hymn to Ra from the Book of the Dead

This hymn to Ra, from the Egyptian Book of the Dead, offers a glimpse at the Egyptian reverence for their gods. It goes: NEKHT, THE CAPTAIN OF SOLDIERS, THE ROYAL SCRIBE, SINGETH A HYMN OF PRAISE TO RA, and saith: Homage to thee, O thou glorious Being, thou who art dowered [with all sovereignty]. O Tem-Heru-Khuti (Tem-Harmakhis), when thou risest in the horizon of heaven a cry of joy goeth forth to thee from all people. O thou beautiful Being, thou dost renew thyself in thy season in the form of the Disk, within thy mother Hathor. Therefore in every place every heart swelleth with joy at thy rising for ever. The regions of the South and the North come to thee with homage, and send forth acclamations at thy rising on the horizon of heaven, and thou illuminest the Two Lands with rays of turquoise-[coloured] light. O Ra, who art Heru-Khuti, the divine man-child, the heir of eternity, self-begotten and self-born, king of the earth, prince of the Tuat (the Other World), governor of Aukert, thou didst come from the Water-god, thou didst spring from the Sky-god Nu, who doth cherish thee and order thy members. O thou god of life, thou lord of love, all men live when thou shinest; thou art crowned king of the gods. The goddess Nut embraceth thee, and the goddess Mut enfoldeth thee at all seasons. Those who are in thy following sing unto thee with joy, and they bow down their foreheads to the earth when they meet thee, the lord of heaven, the lord of the earth, the King of Truth, the lord of eternity, the prince of everlastingness, thou sovereign of all the gods, thou god of life, thou creator of eternity, thou maker of heaven wherin thou art firmly established. [Source: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt, Fordham University]

“The Company of the Gods rejoice at thy rising, the earth is glad when it beholdeth thy rays; the people who have been long dead come forth with cries of joy to behold thy beauties every day. Thou goest forth each day over heaven and earth, and thou art made strong each day be thy mother Nut. Thou passest over the heights of heaven, thy heart swelleth with joy; and the Lake of Testes (the Great Oasis) is content thereat. The Serpent-fiend hath fallen, his arms are hewn off, the Knife hath severed his joints. Ra liveth by Maat (Law), the beautiful! The Sektet Boat advanceth and cometh into port. The South and the North, and the West and East, turn to praise thee. O thou First, Great God (PAUTA), who didst come into being of thine own accord, Isis and Nephthys salute thee, they sing unto thee songs of joy at thy rising in the boat, they stretch out their hands unto thee. The Souls of the East follow thee, and the Souls of the West praise thee. Thou art the Ruler of all the gods. Thou in thy shrine hast joy, for the Serpent-fiend Nak hath been judged by the fire, and thy heart shall rejoice for ever. Thy mother Nut is esteemed by thy father Nu.

“ HYMN TO OSIRIS UN-NEFER: A Hymn of Praise to Osiris Un-Nefer, the great god who dwelleth in Abtu, the king of eternity, the lord of everlastingness, who traverseth millions of years in his existence. Thou art the eldest son of the womb of Nut. Thou was begotten by Keb, the Erpat. Thou art the lord of the Urrt Crown. Thou art he whose White Crown is lofty. Thou art the King (Ati) of gods [and] men. Thou hast gained possession of the sceptre of rule, and the whip, and the rank and dignity of thy divine fathers. Thy heart is expanded with joy, O thou who art in the kingdom of the dead. Thy son Horus is firmly placed on thy throne. Thou hast ascended thy throne as the Lord of Tetu, and as the Heq who dwelleth in Abydos. Thou makest the Two Lands to flourish through Truth-speaking, in the presence of him who is the Lord to the Uttermost Limit. Thou drawest on that which hath not yet come into being in thy name of "Ta-her-sta-nef." Thou governest the Two Lands by Maat in thy name of "Seker." Thy power is wide-spread, thou art he of whom the fear is great in thy name of "Usar" (or "Asar"). Thy existence endureth for an infinite number of double henti periods in thy name of "Un-Nefer."

“Homage to thee, King of Kings, and Lord of Lords, and Prince of Princes. Thou hast ruled the Two Lands from the womb of the goddess Nut. Thou hast governed the Lands of Akert. Thy members are of silver-gold, thy head is of lapis-lazuli, and the crown of thy head is of turquoise. Thou art An of millions of years. Thy body is all pervading, O Beautiful Face in Ta-tchesert. Grant thou to me glory in heaven, and power upon earth, and truth-speaking in the Divine Underworld, and [the power to] sail down the river to Tetu in the form of a living Ba-soul, and [the power to] sail up the river to Abydos in the form of a Benu bird, and [the power to] pass in through and to pass out from, without obstruction, the doors of the lords of the Tuat. Let there be given unto me bread-cakes in the House of Refreshing, and sepulchral offerings of cakes and ale, and propitiatory offerings in Anu, and a permanent homestead in Sekhet-Aaru, with wheat and barley therein-to the Double of the Osiris, the scribe Ani.”

Different Interpretation of Texts in the Book of the Dead

One section of the Book of the Dead text mentioned a “great god, who created himself, created his name, the lord of the circle of gods, to whom not one amongst the gods was equal "; these remarks are couched in terms too general to understand which god was in the poet's thoughts. At all events however he was certainly thinking of one god, not, as the commentators insist, of three different gods. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The learned of the New Kingdom explained the passage in the following manner:

I am the great god, who created hi in self.

Explain it: The great god who created himself is the water; that is the heavenly ocean, the father of the gods.

Another says: it is Ra.

Who created his name, the lord of the circle of gods.

Explain it: That is Ra who created his names for his limbs, and created those gods who attend him.

To whom not one is equal amongst the gods.

Explain it: That is Atum in his sun's disk. Another says: that is Ra, who rises in the eastern horizon of heaven. "

From the variants we have quoted, we see that though some scholars liked to interpret the passage as applying to the one god. Ra, official opinion was certain that the three gods mentioned in the first passage, namely Nun, Ra, and Atum, were here intended. The interpretation of the next passage: “I was yesterday, and I know the morrow," was still more involved. When the deceased thus boasted about himself he only meant that like the other gods he was removed from the limits of time, and that the past and the future were both alike to him. Yet the commentators of the Middle Kingdom were minded to see here a reference to one particular god; according to them the god who was yesterday and knows the morrow was Osiris. This was no doubt an error.

We see that however simple a passage might be, and however little doubt there ought to have been concerning its meaning, so much the more trouble did these expositors take to evolve something wonderful out of it. They sought a hidden meaning in everything, for should not the deepest, most secret wisdom dwell in a sacred book? From the passage: “I am the god Min at his coming forth, whose double feathers I placed on my head," every child would conclude that reference was made to the god Min, who was always represented with two tall feathers on his head; yet this was too commonplace and straightforward for it to be the possible meaning of the text. Evidently something quite different was intended; by Min we must not understand the well-known god of Coptos, but Horus. It was true that Horus did not usually wear feathers on his head; yet for this they found a reason. Either his two eyes were to be understood by the two feathers, or they might have some reference to the two snakes, which not he but the god Atum wore on his head. Both these interpretations of the feathers, especially the latter, were rather too far-fetched to be reasonable, and therefore a welcome was accorded to the ingenious discovery of a scholar of the time of the 19th dynasty, who succeeded in proving from the mythology that there was something like feathers on the head of Horus. His gloss ran thus: "With regard to his double feathers, Isis together with Nephthys went once and placed themselves on his head in the form of two birds — behold that then remained on his head. "

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024