Home | Category: Jewish Holidays / Jewish Holidays

JEWISH HOLIDAYS

Omer Calendar used to count The Omer, the seven-week period between the Jewish holidays of Passover and Shavuot

Most Jewish holidays are movable feasts, whose dates are defined by the Jewish lunar calendar and thus, like Easter, are on different dates every year. Work is forbidden on some Jewish holidays as it is on the Sabbath. The Jewish day begins at sunset, which means that all Jewish holidays begin the evening before their western date. Holidays begin at sunset, often with a service after sundown.

Mitzvot (Jewish Laws) Related to Festivals

P 42 — The New Moon Additional Offering

P 44 — The Meal Offering of the Omer

P 52 — The three annual pilgrimages

P 53 — Appearing before the L-rd during the Festivals

P 54 — Rejoicing on the Festivals

P153 — Determining the New Moon

P161 — Counting the Omer

Jewish holidays can last for different lengths of time, depending on the tradition from which a particular Jew or Jewish family or congregation comes. The Jewish liturgical calendar has five major biblically-ordained special days and two principal minor festivals established by the Talmudic sages. While on the Sabbath all work is forbidden, on the major holidays the preparation of food is permitted. The major holidays are Rosh Hashanah; Yom Kippur, which is regarded as the Sabbath, with all work whatsoever forbidden; Sukkoth; Passover; and Shabuoth. In biblical times the latter three were celebrated by pilgrimages to the Temple in Jerusalem. The two principal minor festivals introduced by the rabbis are Hanukkah and Purim, which do not carry the prohibition against working or engaging in mundane activities. Similar rules apply to other minor festivals and fast days. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

According to the BBC: “Outside Israel, Jewish festivals sometimes last one day longer. This has an historical basis in the difficulties faced accurately determining the Jewish calendar based on the lunar cycle. Jews living outside Israel being unsure of a festival's exact date would celebrate for an extra day. Although dates can be calculated accurately now, many non-Israeli Jews still follow this practice.” [Source: September 13, 2012, BBC]

According to the book of Deuteronomy in the Bible, Jews are to celebrate three pilgrimage festivals a year: “Three times a year all your males shall appear before the Lord your God at the place which he will choose at the Feast of the Unleavened Bread, at the Feast of Weeks, and at the Feast of Booths.”

Rosh Hashana (New Year) and Yom Kippur ( Day of Atonement) are periods of fasting, forgiveness, reflection and penitence. Hanukkah and Purim commemorate the saving of Jews from desperate situations. The Feast of the Unleavened Bread is Passover (the liberation of the Jews from Egypt). The Feast of Weeks is Shavuot. The Feast of Booths is Sukkoth. During ancient times these were the great festivals in which Jews were obligated to make visits to the Temple and make sacrifices.

See Separate Articles: PASSOVER: STORIES, CUSTOMS AND THE HAGGADAH africame.factsanddetails.com ; PASSOVER FOODS africame.factsanddetails.com ; PURIM: ESTHER, PASTRIES AND CELEBRATIONS africame.factsanddetails.com ; HANUKKAH: HISTORY, CELEBRATING IT AND JELLY DONUTS africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Encyclopædia Britannica, britannica.com/topic/Judaism; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Jewish Museum London jewishmuseum.org.uk ; Jewish History: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Aish.com aish.com ; Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Jewish Holidays” by Michael Strassfeld Amazon.com ;

“Your Guide to the Jewish Holidays: From Shofar to Seder” by Cantor Matt Axelrod Amazon.com ;

“The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays” by Irving Greenberg Amazon.com ;

“My Jewish Year: 18 Holidays, One Wondering Jew” by Abigail Pogrebin and A.J. Jacobs Amazon.com ;

“The Jewish Holiday Table: A World of Recipes, Traditions & Stories to Celebrate All Year Long” by Naama Shefi. Devra Ferst Amazon.com ;

“The Passover Haggadah: An Ancient Story for Modern Times” by Alana Newhouse and Tablet Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Guide for the Perplexed” by Moses Maimonides, Andrea Giordani, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Jewish Calendar

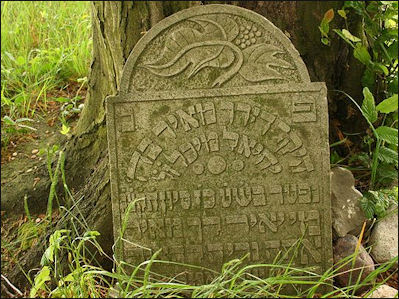

Died in 1833, 5593 on the Jewish calendar The Jewish calendar begins at 3760 B.C., identified as the moment creation began. The date differs from the 4004 B.C. date determined by Archbishop Usher for the Christians but was attained using similar methodology. The year 2000 on the modern calendar was 5760 on the Jewish calendar. It ran from late September 1999 to late September 2000. Talmudic traditions divides history into three periods of 2,000 years each: an age of confusion (from Creation to Abraham); the age of Torah (from Abraham afterwards); and the age of redemption (the period before the coming of the Messiah).

The Jewish calendar is a lunar calendar in which each month begins with the appearance of a new moon and consists of twelve 29 or 30 day. Because these months add up to 354 days a year an extra month is added approximately every leap year so it is in synch with the solar year, and sometimes days are moved around to make sure that the Sabbath does not coincide with certain festivals.Traditionally Jews outside of Israel celebrated festivals one day longer to make sure the messenger that left from Jerusalem to announce the new moon arrived in time. Today, only Orthodox Jews continue the practice.

Jewish months: Nissan (March-April); Iyar (April-May); Sivan (May-June); Tammuz (June-July); Av (July-August); Elul (August-September); Tishri (September-October); Cheshvan (October-November); Kislev (November-December); Tevet (December-January); Shevat (January-February); Adar I, leap years only (February-March); Adar, called Adar Beit in leap years (February-March). [Source: BBC]

Jewish Annual Holiday Cycle

Jewish holidays and festivals are ordered according to the ancient Jewish lunar calendar, made up of lunar months and occasional adjustments to keep the seasons in synch with the solar year. Paul Mendes-Flohr wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: The Jewish New Year, or Rosh Hashanah, falls on the lst of the month of Tishri, which generally corresponds to a day in September. Literally "head of the year," the holiday is also known as the Day of Judgment (Yom Ha-Din), on which a person stands before God, who judges his or her personal repentance. God's judgment is dispensed 10 days later, on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Purim celebration

Rosh Hashanah is a festive celebration of divine creation and, at the same time, a solemn reckoning of one's sins. The period between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur is known as the Days of Awe and is devoted to penitential prayer, which culminates with the fasting and intense expression of contrition and atonement that mark Yom Kippur. On this, the holiest day of the Jewish year, on which God's judgement is cast, Jews pray to be pardoned for their sins and for reconciliation with God.

Five days after Yom Kippur, on the 15th of Tishri, the autumn festival of Sukkoth (Tabernacles) takes place. Lasting a week, the festival is marked by the construction of provisional booths, or sukkahs (from the Hebrew sukkoth), as a reminder of the structures in which the Israelites dwelt during their 40 years' journey in the wilderness (Lev. 23:42). The roof of the sukkah, in which a person is to eat and, if possible, sleep for the duration of the festival, is to be made from things that grow from the ground, a symbol of God's care for the earth and its inhabitants. On the last day of the festival, called Hoshanah Rabbah (Great Hosannah), hymns are sung appealing to God for deliverance from hunger. Sukkoth is followed immediately by Shemini Atzeret, the "eighth day of assembly," on which God is entreated to bestow rain to ensure a good harvest, and the next day is Simhat Torah (Rejoicing of the Torah). On this day the annual cycle of the reading of the Torah is completed, hence the rejoicing. In the Land of Israel, Shemini Atzeret and Simhat Torah are observed on the same day.

Rosh Hashanah

Rosh Hashanah (Rosh ha-Shanah) is the Jewish New Year. Usually falling in September, it is a two day festive occasion that begins with the blowing of a ram's horn in the synagogue during a service that is held after sundown on the eve of the holiday. Numbers 29:1 reads: ‘On the first day of the seventh month hold a sacred assembly and do no regular work. It is a day for you to sound the trumpets.’It has traditionally been a time when families gathered together, attended synagogue services, sent cards and ate honeycakes and apples dipped in honey to symbolize an upcoming sweet year.

Rosh Hashanah is also known as the Day of Judgment, , “Head of the Year” or "Feast of Trumpets". It takes place on the first and second days of the Jewish month of Tishri. Tishri is the seventh month of the Jewish calendar. Nissan is the first month, but Tishri marks the "new year" because that is when the number indicating the year is increased by one. Rosh Hashanah is supposed to be a time for reflection and making resolutions for the new year. Work is not permitted. Observant Jews spend most of the day in a synagogue. The blowing of the shofar, the ram's horn trumpet serves as a call to repentance. "Casting off" is when Jews walk to a body of flowing water and empty their pockets into it, suggesting a casting off of sins. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

During Biblical times “Rosh ha-Shanah” apparently was not associated with the new year but rather it was a "memorial proclaimed with the blast of horns" commemorating Abraham's sacrifice of a ram instead of his son Isaac (Muslims celebrate the same event but say it was Abraham's other son Ishmael who was not sacrificed and celebrate it on a different day).

Celebrating Rosh Hashanah

Rosh Hashanah (1-2 Tishri) commemorates the creation of the world and lasts for two days. is the Jewish New Year, when Jews believe God decides what will happen in the year ahead. According to the BBC: "The synagogue services for this festival emphasise God's kingship and reflect on God's time for judgement. Jews believe God balances a person's good deeds over the last year against their bad deeds and decides their fate accordingly. God records the judgement in the Book of Life, where he sets out who is going to live, who is going to die, who will have a good time and who will have a bad time during the next year. The book and the judgement are finally sealed on Yom Kippur. That's why another traditional Rosh Hashanah greeting is "Be inscribed and sealed for a good year" . [Source: BBC, September 23, 2011; September 13, 2012]

Gefilte fish balls for Rosh Hashanah

“A lot of time is spent in the synagogue on Rosh Hashanah, when there are special services that emphasise God's kingship. The traditional greeting between Jews is "L'shanah tovah" ... "for a good New Year". The blowing of the Shofar is done a hundred times in a special rhythm. Mitzvot (Jewish Laws) Related to Rosh Hashana

P 47 — The Rosh Hashana Additional Offering

P163 — Resting on Rosh Hashana

P170 — Hearing a Shofar on Rosh Hashana

N326 — Not to work on Rosh Hashana

“New Year isn't only celebrated in the synagogue, but at home too. A special meal is served, with the emphasis on sweetness. Apples are dipped in honey, as a symbol of the sweet New Year that each Jew hopes lies ahead. A sweet carrot stew called a tzimmes is often served. And at New Year the Jewish Hallah (or Challah) bread served comes as a round loaf, rather than the plaited loaf served on the Sabbath, so as to symbolise a circle of life and of the year. There's often a pomegranate on the table because of a tradition that pomegranates have 613 seeds, one for each of the commandments that a Jew is obliged to keep.” |::|

Ten Days of Awe (Days of Repentance)

The 10 days beginning with Rosh Hashanah are known as the Ten Days of Awe (“Yamin Noraim”, Days of Repentance) during which Jews are expected to find all the people they have hurt during the previous year and apologise to them. They have until Yom Kippur to do this. Yom Kippur marks the end of the 10 period, also called the High Holy Days of Judaism.

The “Ten Days of Awe” commences at the beginning of the seventh Jewish month in September or October. According to the BBC: “The judgements made at Rosh Hashanah and the plans that God has in mind for a person’s next year are only provisional. God is merciful and offers people a chance to sort out all the things they’ve done wrong. That’s fortunate, as most people are likely to have quite a lot of bad deeds around. So during the 10 days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur everyone gets a chance to repent (teshuvah). [Source: BBC, July 9, 2009 |::|]

“This involves a person admitting that they’ve done wrong and making a firm commitment not to do that wrong again. But there’s more to it — Judaism does not accept forgiveness on behalf of other people, and God can only forgive a person for sins they committed against God. So Jews are expected to find all the people they have hurt during the previous year and apologise to them. And it must be a sincere and an effective apology. As you can imagine, a lot of making-up for hurts and insults goes on in the Jewish world during this period. It is very healing time for both individual and community. |::|

“Jews can also make up for the wrongs of the past year by doing good deeds — so this is a time for charitable acts (tzedakah). Jews will also spend much time in prayer (tefilah), seeking to put themselves into a good relationship with God. There’s a ceremony in which Jews symbolically cast away their sins. It’s called tashlich. A Jewish person goes to a river or a stream and, with appropriate prayers, throws some bread into the water. Nobody believes that they’re actually getting rid of their sins in this way, but they are acknowledging their desire to rid themselves of their sins. “|::|

Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur poster Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) is the most sacred and solemn Jewish holiday. On this day Jews believe God makes the final decision on who will live, die, prosper and fail during the next year, and seals his judgement in the Book of Life. It is a day of fasting and worship. The later includes the confession of sins and asking for forgiveness, which is done aloud by the entire congregation at a synagogue. [Source: September 13, 2012, BBC]

Yom Kippur is a day set aside for Jews to atone for their sins against God. One who has sinned against another person is to seek forgiveness from and reconciliation with that person before Yom Kippur. Usually falling in October, during the tenth day of Tishri, Yom Kippur it is a day of fasting, which lasts for 25 hours, beginning an hour before sundown on the previous day and continuing until sundown on Yom Kippur. During the fasting period Jews not only abstain from all food and drink, even water, they also avoid "anointing" themselves (wearing cosmetics or deodorant), washing and bathing, wearing leather shoes (canvas sneakers are often worn by Orthodox Jews), and having sexual relations. Young children, the elderly, and women who are giving or have just given birth to a child, however, are not permitted to fast for health reasons. Older children are allowed to break their fast if it becomes necessary.

Observant Jews treat Yom Kippur like the Sabbath. No work is done. Yom Kippur has traditionally been viewed as the quietest day of the year. Many Jews observe the fast by completely abstaining from food, drink, sex, smoking, washing, using soap or toothpaste and animal products.Time is spent quietly praying, reading the Torah, meditating and confessing one’s sins.

Biblical Basis of Yom Kippur

The scriptural basis for Yom Kippur can be found in Leviticus 16, which describes a series of religious rituals and animal sacrifices that had to be performed in the Jerusalem Temple in order to keep the Temple clean. On Yom Kippur, The Book of Life is closed and sealed, and those who have properly repented for their sins will be granted a happy New Year. According to Leviticus 23:26-28: ‘The Lord said to Moses, "The tenth day of this seventh month is the Day of Atonement. Hold a sacred assembly and deny yourselves, and present an offering made to the LORD by fire. Do no work on that day, because it is the Day of Atonement, when atonement is made for you before the LORD your God."’

Candida Moss wrote: Ritual sacrifices were offered year round so it’s strange that a special day was required, but Yom Kippur was something like a religious deep clean. Professor Liane Feldman, who teaches in the department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies at NYU, explained that “anything that slipped through the cracks or hasn’t been cleaned up yet or can’t be cleaned up by regular [sacrificial] offerings is taken care of by a series of five sacrifices offered on this day.” The reason behind the obsession with ritual cleanliness is that the Temple was the home of God. As Feldman puts it. “the Israelite God cannot live in an impure place.” If the Temple gets too dirty then there’s the risk that God might leave (which is a thing that God actually does in Ezekiel). [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, October 8, 2019]

The most intriguing part of the religious rituals is the mention of a goat over which the high priest confesses the sins of the Israelites and transfers the sins from the Temple to the goat. These sins are the most serious kind: they are intentional sins (sins you deliberately and brazenly commit). “The contamination caused by intentional sins can’t be cleaned up, it can only be moved from one place to another,” said Feldman. After the transfer of sins to the goat, to which was attached a red yarn collar, the goat was dispatched into the wilderness to “Azazel.” Writing sometime later, the rabbis — who were understandably concerned that the goat might trot back with its burden — weren’t content to just send the goat into the wilderness and, thus, insisted that the goat be pushed off a cliff and died. Feldman mentioned one rabbinic tradition in which a piece of red yarn is also tied to the Temple door. When the goat gets outside the community the yarn is supposed to turn white. The ritual is the origins of the modern term “scapegoat.”

Mitzvot (Jewish Laws) Related to Yom Kippur

P 48 — The Yom Kippur Additional Offering

P 49 — The Service of Yom Kippur

P164 — Fasting on Yom Kippur

P165 — Resting on Yom Kippur

N329 — Not to work on Yom Kippur

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “ How Christianity Co-Opted Yom Kippur to Explain Jesus’ Death” by Candida Moss in the Daily Beast thedailybeast.com

Yom Kippur Service

Much of Yom Kippur is spent in the synagogue. Services typically last from midmorning to midafternoon, then resume in the evening. The liturgy (religious practice) that is followed is much more complex than that followed on other occasions and requires a special prayer book, the machzor. During the services Jews confess their sins (in the plural, emphasizing communal responsibility for sin) and make vows for the future.

At the services The Book of Jonah is read and rabbi is asked to atone the entire community, a ritual that dates back to biblical times. The purpose is similar to Catholic confession. The evening Yom Kippur services are brought to end with blowing of the ceremonial ram's horn.

According to the BBC: "The most important part of Yom Kippur is the time spent in the synagogue. Even Jews who are not particularly religious will want to attend synagogue on Yom Kippur, the only day of the year with five services. The first service, in the evening, begins with the Kol Nidre prayer. Kol Nidre's words and music have a transforming effect on every Jew—it's probably the most powerful single item in the Jewish liturgy. The actual words of the prayer are very pedestrian when written down — it's like something a lawyer might have drafted asking God to render null and void any promises that a person might make and then break in the year to come — but when sung by a cantor it shakes the soul. [Source: BBC, October 6, 2011 |::|]

“To emphasise the special nature of the service the men in the synagogue will put on their prayer shawls, which are not normally used in an evening service. Another element in the liturgy for Yom Kippur is the confession of sins (vidui). Sins are confessed aloud by the congregation and in the plural. The fifth service is "Neilah", and brings the day to a close as God's judgement is finally sealed. The service beseeches God to hear the prayers of the community. For this service the whole congregation stands throughout, as the doors of the Ark are open. At the end of the service the shofar is blown for the final time.” |::|

Israel Shun Yom Kippur Clock Change

Yom Kippur War in 1973

In 2010, Yom Kippur coincided with the clock change for daylight savings time, when darkness comes an hour earlier. Joel Greenberg wrote in the Washington Post, “In Tel Aviv, Gil Leibowitz was heading down to the beach on a recent evening to "clear his head," as he put it, with a walk, a run and a sunset swim — the software engineer's after-work summer ritual. It was about 6:30 p.m., in the last hour of light before the sun dropped into the Mediterranean. On Sunday, Leibowitz's routine, and those of many Israelis, will be disrupted when Israel abruptly goes off daylight saving time well before summer weather ends, bringing darkness before 6 p.m. even as temperatures linger in the 80s. "This is going to kill off my fun," Leibowitz said. "There's no point in coming here in the dark." [Source: Joel Greenberg, Washington Post, September 7, 2010 ]

“The earlier plunge into darkness this year is linked to the early onset of the Jewish High Holidays and the approach of the Yom Kippur fast next week. According to a five-year-old law negotiated with the ultra-Orthodox Shas party, Israelis must turn back their clocks one hour on the Sunday before Yom Kippur. That way, the 25-hour fast, from sundown to sundown, ends shortly before 6 p.m. instead of 7 p.m., creating the impression of an earlier end to a trying day.

“Setting back the national clock to accommodate the faithful on the holiest day of the Jewish calendar has generated controversy in the past, but this year the argument is raging with greater intensity because of the early date of the shift, weeks ahead of Europe and the United States. Nearly 200,000 Israelis have signed an online petition urging people to resist the change and not turn back their clocks. The debate has drawn battle lines in the ongoing struggle in Israel over the role of religion in public life, highlighting the power of ultra-Orthodox parties in Israel's governing coalitions.

“Critics of the early time shift argue that because of the demands of a religious minority, Israelis will rise when the sun is higher and hotter, come home from work in the dark, and spend more time with their lights turned on, costing the national economy millions of dollars. According to the Manufacturers Association of Israel, the 170 days of daylight saving time this year saved more than 26 million dollars.

The early time shift in Israel has a parallel only in the West Bank areas controlled by the Palestinian Authority and in the Hamas-ruled Gaza Strip, where the clock was turned back last month to help people fasting from dawn to sundown during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. "At the height of summer, winter will begin here," Nehemia Shtrasler, economic editor of the liberal Israeli daily Haaretz, lamented in his annual screed against the time change. "It won't happen in any other state in the world, not even Iran. Only here has the religious, ultra-Orthodox minority succeeded in imposing its will on the majority."

Sukkot

“Sukkot” (Feast of Booths) is a nine day festival (emphasis on first two days) that begins four days after Yom Kippur on the 15th day of the seventh Jewish lunar month (in October). It commemorates the Israelites wandering in the desert with the building of a small roofless shelters called a “sukkahs” . The last day is celebrated with a procession of the scrolls and a reading of “Genesis “ and “Deuteronomy” .

Sukkot (15-21 Tishri) is also spelled or written Succot, Sukkos or Sukkoth. According to the BBC: “Sukkot commemorates the years that the Jews spent in the desert on their way to the Promised Land, and celebrates the way in which God protected them under difficult desert conditions.

Sukkot at the Western Wall in Jerusalem Sukkot is also known as the Feast of Tabernacles, or the Feast of Booths. Leviticus 23:42 reads: ‘You shall dwell in sukkot seven days...in order that future generations may know that I made the Israelite people live in sukkot when I brought them out of the land of Egypt, I the Lord your God.’ [Source: BBC, October 12, 2011 |::|]

Mitzvot (Jewish Laws) Related to Sukkos

P 50 — The Sukkos Offering

P 51 — The Shemini Atzeret Additional Offering

P166 — Resting on the first day of Sukkos

P168 — Dwelling in a Sukkah for seven days

P169 — Taking a Lulav on Sukkos

N327 — Not to work on the first day of Sukkos

Celebrating Sukkot

Sukkot commemorates the years spent wandering the desert during The Exodus when Jews lived in makeshift dwellings. For the duration of the festival Jewish families live in temporary huts called sukkot (singular: sukkah) that recall the makeshift huts of the desert and are built out of branches and leaves. Each day they hold celebrations with four types of plant: branches of palm, myrtle and willow and a citrus fruit called an etrog. Sukkot is intended to be a joyful festival that lets Jews live close to nature and know that God is taking care of them. [Source: September 13, 2012, BBC]

Sukkot also commemorates the bringing of the first fruits to the Temple in Jerusalem. Some families hang fruits on their sukkahs and eat rolled cabbage, which stays warm while it is transferred from a house to a booth. Other foods associated with Sukkot include figs and pomegranates and etrogs.

Etrogs are a kind of citron. They are eaten by Jews who follow the command to recite prayers over “the fruit of goodly trees.” Thought to have been one of the fruits in the Garden of Eden, etrogs have thick skins, look like large lemons and taste like bitter lemons. According to Jewish law, the fruit has to be peeled or not have any scars or it cannot be used. Sometimes magnifying glasses are used to find fruits that are unblemished. During a special Sukkoth blessing etrogs are held in the left hand and a date palm branch entwined with myrtle and a willow branch is held in the right hand and carried through a synagogue to symbolize the presence of God throughout the world.

Shemini Atzeret is an extra day after the end of Sukkot. According to the BBC: Jews spend some time in their sukkah, but not as much, and without some of the rituals. Simchat Torah (22 Tishri; outside Israel Simchat Torah is 23 Tishri) means "Rejoicing in the Torah". Synagogues read from the Torah every week, completing one read-through each year. They reach the end on Simchat Torah and this holiday marks the completion of the cycle, to begin again the next week with Genesis. [Source: September 13, 2012, BBC]

Sukkot Sukkahs

The sukkahs represents the Israelites sleeping under the stars. They are usually cobbled together from scraps of plywood and have only loose branches for a roof. The are set up in backyards, balconies, gardens, hotels and restaurants.

sukkah in Tel Aviv

According to the BBC: “The word sukkot means huts (some translations of the bible use the word booths), and building a hut is the most obvious way in which Jews celebrate the festival.’ Every Jewish family will build an open air structure in which to live during the holiday. The essential thing about the hut is that it should have a roof of branches and leaves, through which those inside can see the sky, and that it should be a temporary and flimsy thing. The Sukkot ritual is to take four types of plant material: an etrog (a citron fruit), a palm branch, a myrtle branch, and a willow branch, and rejoice with them. (Leviticus 23: 39-40.) People rejoice with them by waving them or shaking them about. |::| [Source: BBC, October 12, 2011 |::|]

“Most people nowadays live in houses or apartments with strong walls and a decent roof. Spending time in a fragile hut in the garden, or under a roof of leaves rigged up on a balcony gives them the experience of living exposed to the world, without a nice comfy shell around them. It reminds them that there is only one real source of security and protection, and that is God. Similarly, the holes in the roof reveal the sky, and metaphorically, God's heaven, the only source of security. Another meaning goes along with this: a Jew can be in God's presence anywhere. The idea here is that the person, having abandoned all the non-natural protections from the elements has only God to protect them — and since God does protect them this shows that God is there. A sukkah must also have at least two walls and part of a third wall. The roof must be made of plant materials (but they must have been cut from the plant, so you can't use a tree as the roof). |::|

“Jews don't live in these huts too completely; it depends on the climate where they live. People in cold countries can satisfy the obligation by simply taking their meals in the huts, but in warmer countries, Jewish people will often sleep out in their huts. What Jewish law requires is that the hut should be a person's principal residence. The festival is set down in the Hebrew Bible book of Leviticus: ‘You shall dwell in booths seven days, that your generation shall know I made the children of Israel to dwell in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt.’” |::|

Sukkot Message from a Rabbi

On Sukkot, Chief Rabbi Dr Jonathan Sacks told the BBC: “It's a simple festival. We take a palm branch, a citron, and some leaves of myrtle and willow, to remind ourselves of nature's powers of survival during the coming dark days of winter. And we sit in a sukkah, the tabernacle itself, which is just a shed, a shack, open to the sky, with just a covering of leaves for a roof. It's our annual reminder of how vulnerable life is, how exposed to the elements. [Source: Chief Rabbi Dr Jonathan Sacks, BBC |::|

sukkah in Jerusalem

“And yet we call Sukkot our festival of joy, because sitting there in the cold and the wind, we remember that above us and around us are the sheltering arms of the divine presence. If I were to summarise the message of Sukkot I'd say it's a tutorial in how to live with insecurity and still celebrate life. And living with insecurity is where we're at right now. In these uncertain days, people have been cancelling flights, delaying holidays, deciding not to go to theatres and public places. The physical damage of September 11th may be over; but the emotional damage will continue for months, maybe years, to come. |::|

“Yesterday a newspaper columnist wrote that looking back, future historians will call ours "the age of anxiety." How do you live with the fear terror creates? For our family, it's brought back memories of just over ten years ago. We'd gone to live in Israel for a while before I became Chief Rabbi, to breathe in the inspiration of the holy land and find peace. Instead we found ourselves in the middle of the Gulf War. Thirty-nine times we had to put on our gas masks and take shelter in a sealed room as SCUD missiles rained down. And as the sirens sounded we never knew whether the next missile would contain chemical or biological warheads or whether it would hit us. |::|

“It should have been a terrifying time, and it was. But my goodness, it taught me something. I never knew before just how much I loved my wife, and our children. I stopped living for the future and started thanking God for each day. And that's when I learned the meaning of Tabernacles and its message for our time. Life can be full of risk and yet still be a blessing. Faith doesn't mean living with certainty. Faith is the courage to live with uncertainty, knowing that God is with us on that tough but necessary journey to a world that honours life and treasures peace.” |::|

Shavuot

Shavuot" ("Weeks”) is a two day festival that takes place in late May or early June, six weeks after Passover ends. It celebrates the offering of the first fruits and the revealing of the Ten Commandments to Moses. Most of the foods eaten in this day are cheese products. Most businesses are closed.

Shavuot (6 Sivan) is also spelled and written Shavuos or Shabuoth . Priginally a harvest festival, its is now observed in commemoration of the giving of the Torah to the Israelites at Mt.Sinai. Historically, at this time of year the first fruits of the harvest were brought to the temples. Shavuot is marked by prayers of thanks for the Holy Book and study of its scriptures. Customs include decorating synagogues with flowers and eating dairy foods. Mitzvot (Jewish Laws) Related to Shavuos

P 45 — The Shavuos Additional Offering

P 46 — Bring Two Loaves on Shavuos

P162 — Resting on Shavuos

Shavuot

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: Shabuoth falls on the 6th (in the Diaspora on the 6th and 7th) of Sivan, the ninth month after Tishri. It takes place 50 days after the Omer (sheaf of barley) was taken to the Temple on the second day of Passover. (Hence, it is called Pentecost [Greek for "50"] in Christian sources.) In biblical times Shabuoth was a harvest holiday, and it is celebrated as such by many secular Israelis today. The rabbis, however, understood its principal significance to be a commemoration of the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai. The portion of the Torah read on the first day of Shabuoth is from Exodus (19:1–20:26). On the second day, in the Diaspora, a parallel passage from Deuteronomy 16:1–17 is read. It is also customary to read the Book of Ruth on Shabuoth, for of her own volition Ruth the Moabite entered into the covenant of Abraham. She is, therefore, the paradigm both of pure faith and of a genuine convert to Judaism. According to Jewish tradition, Ruth's grandson, King David, died on Shabuoth. Although there are no special rituals to mark Shabuoth, many customs have evolved over the centuries. The eating of dairy dishes, some especially prepared for the day, is a particularly popular custom. The Kabbalist custom of devoting the entire night of Shabuoth to Torah study was later adopted by other Jewish communities.[Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Shavuot is one of the Jewish harvest festivals (The other two Jewish agricultural festivals are Passover and Sukkot) and takes place seven weeks (fifty days) after Passover. According to the BBC: “This time of year marks the start of the wheat harvest and the end of the barley harvest. Shavuot also marks the time that the Jews were given the Torah on Mount Sinai. It is considered a highly important historical event. Shavuot is sometimes called the Jewish Pentecost. The word Pentecost here refers to the count of fifty days after Passover. The Christian festival of Pentecost also has its origins in Shavuot. [Source: BBC May 18, 2010 |::|]|

“Prayers are said on Shavuot (especially at dawn) to thank God for the five books of Moses (collectively known as the Torah) and for his law. Some people also spend the first night of Shavuot studying the Torah. Synagogues are decorated with flowers and plants on this joyous occasion to remember the flowers of Mount Sinai. Dairy products are eaten during Shavuot. There are many interpretations about why this custom is observed. It is believed that once the rules about the preparation of meat were revealed in the Torah, the people of Sinai were reluctant to eat meat until they fully understood the rules.” |::|

Tisha B'av (Ninth of Av)

Tisha B'Av (9 Av) is a day of commemoration for a series of tragedies that have befallen the Jewish people, some of which coincidentally happened on this day, for example the destruction of the first and second temples in ancient Jerusalem. Other tragedies are commemorated on this day, such as the beginning of World War I and the Holocaust. Tisha B’Av falls in July or August on the 9th day of the Hebrew month of Av. [Source: September 13, 2012, BBC]

Tisha B'av in Ahmedabad, India

As Tisha B'Av is a day of mourning Jews observe a strict fast and avoid laughing, joking and chatting. Synagogues are dimly lit and undecorated and the Torah draped in black cloth.” According to the BBC: “ The days of tragedy include the destruction of the first temple in Jerusalem in 586 BCE by Nebuchadnezzar when 100,000 Jews were believed to have perished, and the destruction of the second temple by the Romans in 70 CE. Tisha B'av is observed with prayers and fasting. Shaving and the wearing of cosmetics and leather are banned, and people are also expected to refrain from smiles, laughter and idle conversation. All ornaments are removed from synagogues and lights are dimmed. The ark (where the Torah is kept) is draped in black. The Book of Lamentations, written by the prophet Jeremiah after the destruction of the First Temple, is read at evening services. [Source: BBC, July 13, 2011 |::|]

Shmuel Herzfeld wrote in the New York Times, “The month of Av, a period of increasingly intense mourning that culminates with a total fast on the Ninth of Av... One of the customary practices in these nine days is the avoidance of meat: it’s the way we commemorate the destruction of the Temple, where daily animal sacrifices were once brought. Refraining from food is symbolic, of course. The idea is not just to avoid meat but to limit ourselves so that we can better focus on the spiritual.” [Source: Shmuel Herzfeld, New York Times, August 5, 2008]

In Israel it is customary for mourners to congregate at the Western Wall — the last ruins of the Second Temple — to recite kinot or laments for the dead.” Other fast days on the Jewish calendar include the Fast of the 9th Day of Ac in late July or early July; the Fast of Gedalya in September; Shmini Atzeret in late September or early October; and the Fast of the 10th of Tevet in Late December to early January.

Tu B'Shevat (Tu Bishvat)

Tu B'Shevat (15 Shevat) is the Jewish New Year for Trees. The Torah forbids Jews to eat the fruit of new trees for three years after they are planted. The fourth year's fruit was to be tithed to the Temple. Tu B'Shevat was counted as the birthday for all trees for tithing purposes, like the beginning of a fiscal year. On Tu B'Shevat Jews often eat fruits associated with the Holy Land, especially the seven plants mentioned in the Torah: wheat, barley, grapes, figs, pomegranates, olives and dates. Planting trees is another tradition. [Source: September 13, 2012, BBC]

According to the BBC: “Tu B'Shevat is the Jewish 'New Year for Trees'. It is one of the four Jewish new years (Rosh Hashanahs). Deuteronomy 8:7-8 reads: ‘For the LORD thy God bringeth thee into a good land, a land of brooks of water, of fountains and depths, springing forth in valleys and hills; a land of wheat and barley, and vines and fig-trees and pomegranates; a land of olive-trees and honey’ On Tu B'Shevat Jews often eat fruits associated with the Holy Land, especially the ones mentioned in the Torah. [Source: BBC, July 15, 2009 |::|]

Tu B'Shevat

“Tu B'Shevat is a transliteration of 'the fifteenth of Shevat', the Hebrew date specified as the new year for trees. The Torah forbids Jews to eat the fruit of new trees for three years after they are planted. The fourth year's fruit was to be tithed to the Temple. According to Leviticus 19:23-25: ‘And when ye shall come into the land, and shall have planted all manner of trees for food, then ye shall count the fruit thereof as forbidden; three years shall it be as forbidden unto you; it shall not be eaten. And in the fourth year all the fruit thereof shall be holy, for giving praise unto the LORD. But in the fifth year may ye eat of the fruit thereof...’ Tu B'Shevat was counted as the birthday for all trees for tithing purposes: like the beginning of a fiscal year. It gradually gained religious significance, with a Kabbalistic fruit-eating ceremony (like the Passover seder) being introduced during the 1600s. |::|

“Jews eat plenty of fruit on Tu B'Shevat, particularly the kinds associated with Israel. The Torah praises seven 'fruits' in particular: wheat, barley, grapes, figs, pomegranates, olives and dates. A short blessing is recited after eating any fruit. A special, longer blessing is recited for the fruits mentioned in the Torah. Jews also try to eat a new fruit, which can be any seasonal fruit that they have not tasted this year, followed by another blessing. Hassidic Jews may also pray for a perfect etrog, a type of citrus fruit, to use for Sukkot. Some Jews plant trees on this day, or collect money towards planting trees in Israel.” |::|

Yom HaShoah

Yom HaShoah(Holocaust Memorial Day), on the 27th of Nisan, commemorates the killing of 6 million Jews by the Nazis during World War II. It was on this date in 1943 that the Nazis suppressed the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, and thus heroic resistance of Jewish partisans is also remembered on this day. Many Jewish congregations and communities throughout the Diaspora have incorporated Yom Ha-Shoah into their liturgical and communal calendars. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s,

The name “Yom Hashoah" name comes from the Hebrew word 'shoah', which means 'whirlwind'. Established in Israel in 1959 by law, it is celebrated with the lighting of candles for Holocaust victims, and listening to the stories of survivors. Religious ceremonies include prayers such as Kaddish for the dead and the El Maleh Rahamim, a memorial prayer. [Source: BBC, April 27, 2011 |::|]

According to the BBC: “In Israel Yom Hashoah is one of the most solemn days of the year. It begins at sunset on 26th Nissan and ends, like all traditional Jewish special days, the following evening. During Yom Hashoah memorial events are held throughout the country, with national ceremonies being held at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. (Yad Vashem is the Jewish people’s memorial to the murdered Six Million.) On the morning of Yom Hashoah a siren is sounded for two minutes throughout Israel and all work and other activity stops while people remember those killed in the Holocaust.” |::|

Other Jewish Holidays

Yom HaShoah is one of two holidays of the State of Israel that are also observed throughout the Diaspora. The other is Yom Ha-Atzamaut (Israeli Independence Day), on the 5th of Iyyar, the eighth month of the Jewish calendar, which marks the proclamation of the State of Israel on 14 May 1948. Although it is an Israeli civil holiday, Yom Ha-Atzamaut is celebrated in most Jewish congregations with special prayers of thanksgiving. Encyclopedia.com]

“Lag B’Omer” (“33rd day of the Counting of the Omer”) in late May or early June is the one-day lifting of a seven week period of semi morning. It is traditionally a time when bonfires are set and people get married and eat roast potatoes. Children run and around shoot bows and arrows, as their ancestors did, when they were supposed to be studying. Most businesses remain open.

Sephardic Jews celebrate Mainmuna, a festive post-Passover holiday honoring Maimon Ben Joseph, the father of the great 12th century Jewish philosopher Moses Mainmonides. Some American Jews celebrate Christmas. This is considered somewhat sacrilegious by many Jews.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, Library of Congress, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024