Home | Category: Jewish Holidays / Jewish Holidays / Jewish Food

PASSOVER FOOD

Passover Seder foods Passover (Pesach 15-21 Nissan) is arguably the most important Jewish festival. It begins on the fifteenth day of first Jewish month (in March or April) and lasts seven or eight days depending on the practices of individual denominations. The first two days and nights of Passover are the most important. The first two nights are celebrated with a traditional feast ("seder"), in which many of the foods have symbolic meaning. The holiday coincides with Biblical barley harvest and spring festivals. The service opens with the announcement: “All who are hungry...let them come in and eat...All who are needy...let them come on and celebrate the Passover.” At ancient Jewish feasts, food was given out freely to rich and poor alike.

During Passover, Jews remember the story of the Israelites fleeing in Egypt and God unleashed ten plagues on the Egyptians, culminating in the death of every family's eldest son. God told the Israelites to sacrifice lambs and mark their doors with the blood to escape this fate. They ate the lambs with bitter herbs and unleavened bread (unrisen bread without yeast). These form three of the components of the seder There are blessings, songs and other ingredients to symbolise parts of the story. During the meal the adults explain the symbolism to the children. [Source: September 13, 2012, BBC]

Foods with symbolic meaning include: 1) matzo (unleavened, flat bread), representing the haste in which the Israelites left Egypt (they left so quickly their bread did not have time to rise); 2) salt water and hard-boiled eggs dipped in salt, symbolizing the tears shed by their ancestors when they were slaves of the Egyptians; and 3) “maror” (bitter herbs) eaten with a reddish horseradish sauce called “harosth”, representing the bitterness associated with slavery. All these dishes are eaten at stated times.

A roasted lamb eaten at Passover represents the sacrificial lamb ritually slaughtered at the Temple, which in turn represents the lamb killed by the Israelites which supplied the blood they smeared on their doorposts so the Angel of Death would pass over their homes during the Tenth Plague. The lamb is supposed to be unblemished at the prime of its life. Roasting is regarded as symbol of God’s judgement. The feasting at Passover is tinged with the cautionary tale that some were spared but many were not.

Other traditional Passover foods include green herbs (associated with spring), eggs (commemorating festival sacrifice), and “charoset” , a mixture of chopped apples, dates, figs, almonds, wine and cinnamon (recalling the mortar that Jews were required to mix in Egypt). Maror is sometimes dipped in charoset.

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Encyclopædia Britannica, britannica.com/topic/Judaism; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Jewish Museum London jewishmuseum.org.uk ; Jewish History: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Aish.com aish.com ; Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Jewish Holiday Table: A World of Recipes, Traditions & Stories to Celebrate All Year Long” by Naama Shefi. Devra Ferst Amazon.com ;

“The Passover Haggadah: An Ancient Story for Modern Times” by Alana Newhouse and Tablet Amazon.com ;

“The Jewish Holidays” by Michael Strassfeld Amazon.com ;

“Your Guide to the Jewish Holidays: From Shofar to Seder” by Cantor Matt Axelrod Amazon.com ;

“The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays” by Irving Greenberg Amazon.com ;

“My Jewish Year: 18 Holidays, One Wondering Jew” by Abigail Pogrebin and A.J. Jacobs Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Guide for the Perplexed” by Moses Maimonides, Andrea Giordani, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Seder– the Passover Meal

A typical seder meal includes lettuce, lamb bone, charoset, horseradish paste, celery, beetroot paste, and roast egg. Charoset paste is made with walnuts, wine, cinnamon, honey and apples Dark red paste is served with romaine lettuce and horseradish root. To fulfill the three types of herbs requirement: horseradish, whole horseradish root or beetroot paste and lettuce is eaten.

According to the BBC: “The highlight of Passover observance takes place on the first two nights, when friends and family gather together for ritual seder meals. Seder means 'order' in Hebrew and the ceremonies are arranged in a specific order. Special plates and cutlery are used which are kept exclusively for Passover. |[Source: BBC, July 9, 2009 |::|]

During the seder “Four Questions” are asked. “The Four Questions are: 1) Why do we eat unleavened bread? Unleavened bread or matzo is eaten to remember the Exodus when the Israelites fled Egypt with their dough to which they had not yet added yeast. 2) Why do we eat bitter herbs? Bitter herbs, usually horseradish, are included in the meal to represent the bitterness of slavery. 3) Why do we dip our food in liquid? At the beginning of the meal a piece of potato is dipped in salt water to recall the tears the Jews shed as slaves. “4) Why do we eat in a reclining position? In ancient times, people who were free reclined on sofas while they ate. Today cushions are placed on chairs to symbolise freedom and relaxation, in contrast to slavery. Usually the youngest person present will ask the questions and the father will respond. The paradox of this is that these four questions should be asked spontaneously, but celebrations cannot happen unless they are asked! |::|

Passover seder “Each of the components of the Passover meal is symbolic. The food is eaten in ritual order and its meaning and symbolism is discussed. 1) Matzo (unleavened bread) which is eaten symbolically three times during the meal. 2) A bone of a lamb to represent paschal sacrifice. When the Temple at Jerusalem was the centre of Jewish life, Jews would go there at Pilgrim Festivals to sacrifice a lamb or goat. 3) An egg, also to represent sacrifice, but which also has another symbolism. Food usually becomes soft and digestible when cooked, but eggs become harder. So the egg symbolises the Jews' determination not to abandon their beliefs under oppression by the Egyptians. 4) Greenery (usually lettuce) to represent new life.

Salt water to represent a slave's tears. 5) Four cups of wine to recall the four times God promised freedom to the Israelites, and to symbolise liberty and joy. 6) Charoset (a paste made of apples, nuts, cinnamon and wine) to represent the mortar used by the Israelites to build the palaces of Egypt. 7) An extra cup of wine is placed on the table and the door is left open for Elijah. Jews believe that the prophet Elijah will reappear to announce the coming of the Messiah and will do so at Pesach. The concluding words of the Haggadah look forward to this: "Next year in Jerusalem!" |::|

Jonathan Safran Foer wrote in the New York Times: “The most legendary of all Seders — which is, in a postmodern twist, recounted in the Haggadah itself — took place around the beginning of the second century in Bnei Brak, among the greatest scholars of Jewish antiquity. It ended prematurely when students barged in to announce that it was time for the morning prayers. Even if they read the Haggadah from beginning to end, fulfilling every ritual and singing every verse of every song, they must have been spending most of their time doing something else: extrapolating, dissecting, discussing. The story of the Exodus is not meant to be merely recited, but wrestled with.” [Source: Jonathan Safran Foer, New York Times, April 11, 2012 =]

Kitniyot: Rules on Foods Prohibited During Passover

On Passover, Jews are prohibited from eating chametz, a category of foods made from various grains that have been leavened. But for hundreds of years Ashkenazi Jews adopted a custom that takes this prohibition one step further, excluding things like rice and beans, or kitniyot in Hebrew, from a Passover diet, even though they’re not explicitly banned under Jewish law. Their peers from Spain, the Middle East, North Africa and other places, known as Sephardic Jews, didn’t observe the same custom. [Source: Jillian Berman, Market Watch, April 17, 2016]

Dara Lind of Vox wrote: “The actual rules for keeping kosher for Passover aren't about leavening (yeast). They restrict any use of the "five grains" — wheat, spelt (whatever spelt is), barley, oats and rye — that start to "rise" (i.e., ferment) on their own when put in contact with water. The chemistry, and logic, are beside the point. For Ashkenazi Jews — the Jews of Eastern Europe, the heritage of my family and that of many American Jews — the rules have historically gone further. Ashkenazi Jews have traditionally had to avoid corn, rice, peas, beans, peanuts, soybeans, chickpeas — all categorized under the catchall term of kitniyot. [Source: Dara Lind, Vox, April 22, 2016 |=|]

kosher for Passover

“But the rules of kitniyot are falling out of fashion. Toward the end of last year, the Conservative Movement — the institution regulating the second-most-observant of Judaism's three main branches — issued a ruling to conservative Jews saying they could eat kitniyot during Passover if they wanted to. This Passover, many of them will — not to mention less-observant Ashkenazi Jews who didn't need a group of conservative rabbis to tell them not to follow rules that didn't make sense to them.|=|

“Kitniyot is one of these diasporic improvisations. It's a catchall term for other foods that are prohibited during Passover according to Ashkenazi custom. This includes grains that hadn't been native to the Jews of Egypt or their descendants, like corn and rice (though quinoa, a more recent discovery, may or may not count), and any products derived from those. It also includes legumes — beans, peas, soy, peanuts, chickpeas — and the products made from those as well. (The inappropriateness of eating either peanut butter or hummus on matzah is one of the classic gripes of Passover, and is almost a reason to eat matzah the rest of the year — but not quite.) |=|

“There are, in theory, reasons for this. Maybe the rabbis worried that forbidden grains would be mixed into sacks of peas or corn without anyone noticing. Maybe they were confused by the fact that beans swell when water is added to them, even though they're not fermenting. But fundamentally, trying to justify kitniyot is a fool's errand. It makes sense only as a diaspora kludge. |=|

“There's a point in the Passover legend where the escaped slaves, wandering in the desert, start kvetching about the food: They miss the "fish and cucumbers" they were fed in Egypt. The story kind of straw-mans the Hebrew slaves, but it's also a joke for present-day Jews: Slavery sucked, but it's nothing compared to eating nothing but matzah...The point of matzah isn't that eating it makes you feel free. It's asceticism and privation. It's virtue-feeling and forced humility. It's a pain in the ass; it's also a profoundly spiritual experience.” |=|

Matzo, Wine and Christianity

Sometimes during Passover three pieces of unleavened bread are placed in a pile. The upper and lower portions represent the double portion of manna, the food that God gave the Israelites during the Exodus. The middle piece symbolizes the “bread of affliction.” Unleavened bread is believed to be the source of the use of bread in Christian Eucharist (communion). Leaven itself is often associated in the Bible with sin.

During the seder the middle pieces of unleavened bread are plucked out and broken in half. One part is returned to the stack. The part called the “aphikomen” is covered with a napkin and hidden. Often a children’s game is made of finding the hidden piece with a reward of some sort is given the person who finds it. When the hidden piece is returned it is broken, distributed and eaten in quiet refection much like Eucharist bread.

Seders have traditionally featured the drinking of four cups of wine. The third cup is called the Cup of Redemption. It symbolizes the blood from the sacrificed lamb. It is regarded as the source of the cup of wine in Eucharist. During the reading of the Haggadah it is customary to flick drops of wine with the recitation of the list of plagues.

Passover Food Customs

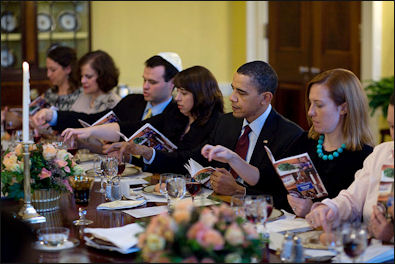

Passover Seder Dinner

at the White House in 2010 One of the most important customs of Passover is the removal of “chametz” (foods made with leaven) from the house. On the night before Passover, it is customary to search the house with a candle looking for the any chametz or chametz crumbs. If some are found they are symbolically swept up with a feather.

Chametz include grain, bread, yeast, cakes, biscuits, crackers, cereals, wheat, barley, rice, dried peas, dried beans, any liquid with grain alcohol, baking soda (because it contains corn starch), and even crumbs. In some cases cooks insist on using milk products that come only from fields supervised by rabbis, , matzo cooked no longer than 18 minutes, and soft drinks made with sugar not corn syrup. Some scholars say that this custom may have its basis in removing grain to keep plague-infested rats from entering the house.

Preparations for Passover include scrubbing the kitchen, removing all forbidden foods, purchasing kosher foods and getting special dishes out of storage. A great effort is made to make sure all “chametz “ are removed. In some cases cooking utensils and dishes are placed in boiling water, and ovens and grills are burned with blow torches to make sure every last particle of chametz is removed. Sometimes the dishes used on Passover are stored away the rest of the year under lock and key. One reason such a fuss is made is that Torah states that God will punish anyone who eats chametz with death.

Often there is some debate about what is allowed and what isn’t. Questions are raised, for example, about whether corn or rice is okay, Things like milk, which don’t need a kosher designation during the rest of the year, need a “kosher for Passover” labeled to be consumed with a clear conscience.” In many cases there are as many interpretations of the rules and the questions 5raised about them are even more confusing.

“Though it means “the telling,” the Haggadah does not merely tell a story: it is our book of living memory. It is not enough to retell the story: we must make the most radical leap of empathy into it. “In every generation a person is obligated to view himself as if he were the one who went out of Egypt,” the Haggadah tells us. This leap has always been a daunting challenge, but is fraught for my generation in a way that it wasn’t for the desperate assimilators of earlier generations — for now, in addition to a lack of education and knowledge of Jewish learning, there is the also the taint of collective complacency. =

“The integration of Jews and Jewish themes into our pop culture is so prevalent that we have become intoxicated by the ersatz images of ourselves. I, too, love “Seinfeld,” but is there not a problem when the show is cited as a referent for one’s Jewish identity? For many of us, being Jewish has become, above all things, funny. All that’s left in the void of fluency and profundity is laughter.” =

Price Gouging During Passover

Jillian Berman wrote in Market Watch: “Passover foods require a special designation, certifying that they live up to typical Jewish dietary restrictions, as well as the added ones for the holiday. Grocery stores and manufacturers have been known to take advantage of this captive audience of Jews that require these special foods. [Source: Jillian Berman, Market Watch, April 17, 2016 /+/]

“When Mark Green was the New York City consumer affairs commissioner in the early 1990s, he tried to curb Passover price gouging through transparency. Green’s agency conducted a price survey of kosher foods ahead of the holiday. In 1990, the price of kosher chicken jumped 4 percent during the three-month survey period and the cost of whitefish, which is often used to make gefilte fish, rose 9 percent, the New York Times reported at the time. /+/

“Green and his commission handed out cards to consumers with the high and low prices of various products in each borough so they could shop around, he recalled in a recent interview. They also placed stores that they decided “measurably overcharge and exploit a religious necessity,” into a so-called Hall of Shanda, a Yiddish term loosely meaning an embarrassment for the community. “While some of it was fun and tongue-and-cheeky, the purpose was serious, which was to save large Orthodox families largely literally hundreds of dollars,” Green said in the interview. He later became New York’s first public advocate and is the author of the forthcoming book, “Bright, Infinite Future: Generational Memoir on Progressive Rise.” /+/

“Passover pricing isn’t as egregious as it used to be, thanks in part to the city’s efforts, according to Menachem Lubinsky, the editor in chief of Kosher Today, a kosher food industry trade publication. “I’ve probably visited 25 stores in the past four or five weeks, I really don’t see it,” he said. These days, there are also more opportunities for Passover observers to shop around, he said. Independent kosher grocers are popping up nationwide and bulk sellers, like Costco have increased their Passover offerings in recent years.” /+/

To Fight Price Gouging Rabbis Say Eating Rice and Beans Okay for the Passover

In late 2015, the Rabbinical Assembly, an international association of Conservative rabbis, issued a ruling, or a teshuvah in Hebrew, expanding the Passover menu for Jewish of Eastern European origin, known as Ashkenazi Jews, to include legumes, rice and corn. Jillian Berman wrote in Market Watch: “The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, the body of the Rabbinical Assembly that issues these types of rulings, decided to clarify its position on kitniyot for a variety of reasons, said Amy Levin, one of the Rabbis who drafted the teshuvah. But one factor they considered was the cost of celebrating the holiday, she said. “There’s a tradition of feeling a certain responsibility to protect the financial resources of the people, not to burden the people in terms of what they need to spend to survive,” she said. [Source: Jillian Berman, Market Watch, April 17, 2016 /+/]

Shmura matzo

“Kosher food, particularly meat, can be expensive, in part because of the extra supervision that’s required to make sure producers accurately follow religious guidelines. “If you go down the aisles of the kosher market and you look at what a brisket costs or a turkey or something else, it’s a lot of money and there are people who are on limited budgets,” Levin said. Without legumes, Ashkenazi families are forced to rely on a relatively expensive source of protein — kosher meat — during the holiday. There’s also a history of price gouging on the Passover, which the teshuvah notes./+/

“The hope is that the new ruling will help increase competition among kosher food producers and sellers and provide Jews with more affordable and healthful options for the holiday, notes Susan Grossman, another rabbi on the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards. Goods bought by the night before Passover that are made exclusively of one item permitted on the holiday — such as raw nuts or a bag of rice — can be used during the holiday as long you say a special blessing, that “annuls” any unexpected trace elements of prohibited items, Grossman said. With the new ruling, Ashkenazi Jews can avoid any inflated Passover prices by buying a bag of rice, or beans, as long as there are no additives, in advance. (Any food purchased during the holiday must be designated as Kosher for Passover, she said.) /+/

“Grossman notes that ancient Rabbis took other steps in the past to make the holiday more affordable, such as allowing Jews to sell their chametz to non-Jews during the duration of the holiday. That way, Jewish grocers or families with large reserves of bread and other banned foods, wouldn’t have to put themselves at financial risk to observe the holiday, which requires that Jews don’t benefit from chametz during Passover. /+/

“Of course some Askhenazi Jews may be cheering the expanded menu for reasons other than price. The rise of vegetarian and vegan diets influenced the rabbis’ decision, Levin noted. Jewish tradition encourages followers to celebrate holidays with joy, something that’s hard to do as a vegetarian on Passover if rice, beans and corn are also banned. For that group and for followers with other health concerns, the ruling “removes any sense of worry or guilt, it just allows for healthier eating choices for them on Passover,” Grossman said.” /+/

“Still, reaction to the decision has been mixed, Levin said. She’s had some Ashkenazi Jews who already ate kitniyot on Passover tell her they’re happy to finally have confirmation it’s allowed. Others say they understand intellectually there’s no provision in Jewish law banning kitniyot on Passover, but years and years of tradition will make it difficult for them to abandon their customs and suddenly start eating burrito bowls during the holiday. The back-and-forth isn’t surprising, given that Jewish tradition is known for its tendency toward robust debate, as the adage goes, “two Jews, three opinions” illustrates. “It’s Jews, so you know there’s going to be lots of different reactions,” Levin quipped.” /+/

Kosher-for-Passover Coke

Paul Lukas wrote in the New Republic: During Passover, Jews are forbidden to eat a category of grains known as kitniot, which includes corn. The Ashkenazi rabbis who came up with this stricture many centuries ago probably didn't foresee how their edict would collide with the invention of high fructose corn syrup (or maybe they did — they were pretty smart dudes). But the end result today is that there are all sorts of HFCS-sweetened products that are kosher for most of the year but are not kosher during Passover. In some cases, special Passover editions of these products — sweetened with cane sugar, which is Passover-sanctioned, instead of HFCS — appear on the market in the weeks leading up to the holiday. And chief among these products is Coca-Cola. [Source: Paul Lukas, New Republic, March 25, 2013]

Coke, of course, used to be made with cane sugar. But as with most American sodas and countless other processed foods, the sugar was replaced by HFCS after the latter's rise to prominence in the late 1970s. So Passover is when Coke gets back to its sucrose roots, so to speak. The sugar-sweetened version, which is distributed in areas with significant Jewish populations, is easy to spot: Just look for the yellow caps.

The thing is, many of the people buying Passover Coke aren't Jews. They're goyim food geeks who prefer sugar over HFCS and snap up the Passover Coke as soon as it hits the stores each spring. (Mexican Coke, which is still made with sugar, can sometimes be found in America, albeit at a significant markup. It enjoys a similarly rarefied status in the foodie-verse.) One reason for this is that HFCS has become a sort of all-purpose bogeyman for the Michael Pollan wing of the foodie set, handily symbolizing a host of societal ills including obesity, corporate chicanery, synthetic foodstuffs, misguided farm subsidy policies, and so on.

The other reason for Passover Coke's popularity among the gastronomic elite is much more straightforward: People think it tastes better. But does it really? This seems like one of those food-fetishisms that sound good on a blog but might fall flat in the real world. And besides, the Coke folks have always claimed that there's no flavor difference.

In an admittedly unscientific attempt to settle the matter, two bottles of Coca-Cola were recently purchased and refrigerated — a standard, HFCS-sweetened bottle and a sugar-sweetened, yellow-capped Passover bottle. A small but expert tasting panel was convened, consisting of this columnist and one of his acquaintances, who we'll call the Cokehead (in part because she likes Coca-Cola but mainly because it's fun to call her that). Soda from each bottle was decanted into identical glasses, each of which had been stocked with a single ice cube. Each member of the tasting panel then administered a blind taste to the other.

The Cokehead sampled both glasses and offered the following stream of commentary: "Oh! This one's stickier. Like, I can feel it on my teeth! It's richer. ... This other one is less substantial. It has a thinner quality to it. I think the first one, the richer one, that's the one with the sugar, right?" The Cokehead was, in fact, correct. The other member of the tasting panel also correctly identified the sugar-sweetened sample (although the purity of his response may have been corrupted by his exposure to the Cokehead's feedback).

Passover Coke Not Allowed in California

Passover matzot

In 2012, Coca-Cola was taken off the menu in California by state laws on toxic chemicals. Associated Press reported: “Coke directed its suppliers last year to change the way they manufacture caramel to reduce levels of the chemical 4-methylimidazole, or 4-MEI, which California has listed as a carcinogen. Although the manufacturing changes didn’t affect the formula or the taste, the resulting product doesn’t meet Jewish dietary laws for Passover, the company said. As a result, the company announced that it will not offer “kosher for Passover” products in California until 2013. [Source: Associated Press, April 6, 2012 /^]

“Passover feasts are better known for ritual wine-drinking, but sodas can be included, although many observant Jews will not use products made with corn during Passover. Although most Coca-Cola uses corn syrup sweetener, the Passover version is made with sugar. A Cokeless Passover is disappointing, said Jason Moss, executive director of the Jewish Federation of the Greater San Gabriel and Pomona Valleys. “I think it would be wonderful for the community to be able to drink a Coke and have a smile,” he told the Pasadena Star-News. /^\

“For those who can’t do without a dose of bubbly brown sweetness, there may be hope. Some kosher stores have stocked Passover Coke from other states. And there’s always Pepsi. As usual, the company is offering its sugar-based Pepsi Throwback, which uses real sugar and is acceptable for Passover, spokeswoman Andrea Canabal said.” /^\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Coke from Coca Cola

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, Library of Congress, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024