Home | Category: Jewish Holidays / Jewish Holidays

HANUKKAH

Hanukkah in the U.S. Hanukkah (“Dedication," or “Festival of Lights”) commemorates an event during the Maccabean revolt when the candelabrum in the Jerusalem Temple miraculously burned for eight days despite only having enough oil for one. The holiday lasts for eight days and begins on the 25th day of Kislev, the ninth Jewish month (usually in December, but sometimes in November), the second month after Tishri. It commemorates the victory of Maccabees — a clan of Jewish warriors also known as the Hasmoneans — over the tyrannical Greek-Syrian Seleucid King Antiochus IV, who had looted and desecrated the Temple of Jerusalem and persecuted the Jews, in 168 B.C. , and prevented them from worshiping at the Temple.

The Maccabees had captured Jerusalem after the three-year war. When they rededicated the temple, they discovered a single cruse of oil with the seal of the High Priest still intact. When they came to light the eight-branched temple candelabrum, the menorah. The menorah miraculously staying lit for eight days became known as the miracle of the oil. During the eight days of Hanukkah, Jews light one extra candle on a special nine-branched menorah, called chanukkiya, each night. They say prayers and eat fried foods to remind them of the oil. Some gifts are exchanged, including chocolate money and special spinning tops called dreidels.

According to the BBC: “Hanukkah dates back to two centuries before the beginning of Christianity. The word Hanukkah means rededication and commemorates the Jews' struggle for religious freedom. The exchange of gifts or gelt is another old and cherished Hanukkah custom that dates back to at least the Middle Ages, possibly earlier. Gelt is the Yiddish term for money. Modern day gelt includes saving bonds, cheques and chocolate coins wrapped in gold foil. [Source: BBC, July 9, 2009 |::|]

Hanukkah (also spelled Chanukah) usually falls around the time of Christmas or before it which is one reason why a big deal is made about in the U.S and Europe. In Israel its not that big of a deal. Families have traditionally lit candles on the “menorah” (a candelabra) each of eight nights. The menorah is an ancient Jewish symbol derived from the candlestick that originally stood in the Temple built by Solomon.

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Encyclopædia Britannica, britannica.com/topic/Judaism; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Jewish Museum London jewishmuseum.org.uk ; Jewish History: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Aish.com aish.com ; Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Jewish Holidays” by Michael Strassfeld Amazon.com ;

“Your Guide to the Jewish Holidays: From Shofar to Seder” by Cantor Matt Axelrod Amazon.com ;

“Hasmonean Realities behind Ezra, Nehemiah, and Chronicles” by Israel Finkelstein Amazon.com ;

“Books of the Maccabees” by King James Bible and Douay Rheims Amazon.com ;

“The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays” by Irving Greenberg Amazon.com ;

“My Jewish Year: 18 Holidays, One Wondering Jew” by Abigail Pogrebin and A.J. Jacobs Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Jewish Holiday Table: A World of Recipes, Traditions & Stories to Celebrate All Year Long” by Naama Shefi. Devra Ferst Amazon.com ;

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Celebrating Hanukkah

Hanukkah is a time for gift giving, although typically only children are given gifts. The chief religious observance is the lighting of the menorah, a nine-branched candelabrum, beginning with one candle on the first night and adding a candle each successive night. Because of the role of oil in the rededication of the Temple, it is traditional for the season to feature fried foods, especially potato pancakes, or latkes.

Also common during Hanukkah is playing with a dreidel, a square top. During the reign of Antiochus, reading the Torah was illegal, but gambling games were not. Jews of the time who had gathered to read the Torah often played with the dreidel to hide what they were actually doing. Dreidels is played using cylindrical four or six-sided dice with handles.

Dreidel is a popular way of helping children to remember the great miracle. A dreidel is a spinning top with a different Hebrew letter inscribed on each of its four sides. The four letters form an acronym that means: 'A great miracle happened here.' The stakes are usually chocolate coins but sometimes pennies, peanuts or raisins are also used. Each player puts a coin in the pot and takes it in turns to spin the dreidel. The letter on which the dreidel stops determines each player's score. Other games include trying to knock other players' dreidels down and trying to spin as many dreidels as possible at any one time. |::|

Lighting the Candles and Religious Practices During Hanukkah

During Hanukkah the candles are lit from right to left during Hanukkah. On day one, the first candle is lit; on the second night Jews light two candles, and the pattern continues. By the eighth night, all eight candles are alight. They are lit from a separate candle, the Shamash or servant candle.

The first night the center candle — which is used for lighting the other candles — is lit. The second night other candles are lit, and so on until all nine candles are lit on the last night. Jews also display a special lamp in the window of their homes;

During Hanukkah Jews follow simple religious rituals in addition to their regular daily prayers from the Siddur, the Jewish prayer book. They recite three blessings during the eight-day festival. On the first night, they recite three and on subsequent nights they say the first two. The blessings are said before the candles are lit. After the candles are lit, they recite the Hanerot Halalu prayer and then sing a hymn.” |::|

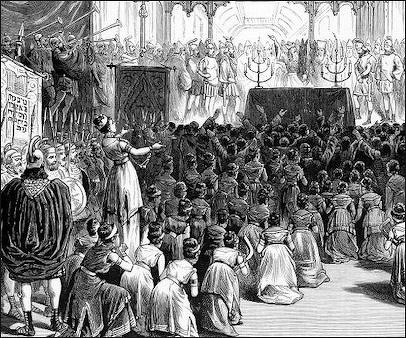

Hanukkah and the Maccabees

Maccabees

Hanukkah celebrated the Maccabees and the restoration of the Jewish — Hasmonean — kingdom in present-day Israel. The Maccabees had captured Jerusalem during a revolt against Antiochus IV. Upon reclaiming the temple, the Jews lit a lamp to rededicate the Temple. Although there was only oil for one day it miraculously lasted for eight days. The story of the I Maccabees is recalled in I Maccabees in The Old Testament.

In 168 B.C., the Hasmoneans (Maccabees) carried a successful revolt against Antiochus Epiphanes of Syria, a tyrannical Greek King who led the Seleucid kingdom and attempted to destroy the Jewish religion and force the Jews to worship pagan idols. Many young Jewish men died as martyrs. The Hasmoneans led by the elderly Mattahias and his five sons captured Jerusalem and rededicated the Temple. The revolt is remembered through the holiday period of Hanukkah. See Hanukkah

The Hasmoneans were a clan of pious and noble Jewish warriors that emerged from the area around Modiin near the border of Samaria and Judea (present-day Israel and the West Bank) . They established a Jewish kingdom that lasted from 168 to 63 B.C. During their brief rule they encouraged everyone to convert to Judaism. There was a long period of chaos, social upheaval and expectations of a Messiah. The Greeks decided to move out. In the mid 1990s a Hasmonean ossuary was found near Modiin. It was the first archaeological proof that the Hasmoneans actually lived in the Modiin area.

See Separate Article: JEWISH INDEPENDENCE AND THE HASMONEAN DYNASTY (MACCABEES) africame.factsanddetails.com

Was Hanukkah Influenced by the Roman Festival Saturnalia

Research into the origins of Hanukkah shows that evolved alongside non-Jewish light-based festivals like Saturnalia, one of the biggest celebration among Romans. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: In the Books of the Maccabees, which describe the first celebration of Hanukkah, there is no reference to lights of the menorah or the miracle of the oil that lasted eight days. Instead, they concentrate on the military victory of the Maccabees over the Greeks and see the festival as a commemoration of the rededication of the Temple (which had been desecrated by the Greeks). Oddly, the first-century Jewish historian Josephus, who first refers to a holiday called the “Festival of Lights,” never calls it Hanukkah or explains why it is associated with light. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 29, 2019]

In 2019, Dr. Catherine Bonesho, an assistant professor in Early Judaism at UCLA, presented a paper on religious competition in the ancient world. In her research, Bonesho examined ancient traditions about Hanukkah preserved in the writings of rabbinic authors in order to see what ancient Jews thought the holiday was about. Bonesho told The Daily Beast that our traditions about Hanukkah started much later than most people know. After Josephus, “the ritual of lighting lamps does not appear in textual form until the Mishnah (200 CE), nor does the tradition of the miracle of oil appear until the Babylonian Talmud (edited between 5th-7th centuries CE),” Bonesho said.

The group known as the rabbis who would eventually write and edit the Babylonian Talmud emerged in Roman Palestine after the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 A.D. They were largely located in Palestine and Sasanian Babylon and “imagined themselves as the leaders of Judaism.” Their influence grew and their writings remain foundational for many Jewish communities to this day. It’s these later traditions found in the Babylonian Talmud that provide the basis for modern celebrations of Hanukkah. But these later discussions of the purpose of Hanukkah didn’t emerge in a vacuum. As the festival of Hanukkah grew and the ritual of candle-lighting moved to the center of its celebration, it did so alongside other religious traditions that also celebrated light and fire.

Hanukkah celebrations in New York in 1880

One important influence, which is often noted in conversations about the origins of Christmas, was the popular ancient Roman festival of Saturnalia. Saturnalia emphasizes the importance of light during the winter solstice. One scholar, Moshe Benovitz, has argued that in the first century B.C. King Herod turned Hanukkah into a kind of solstice festival by associating it with other popular festivals of light. He even claims that in the Roman period the lighting of candles originally marked the solstice, not the oil miracle. For the authors of the Babylonian Talmud, the local Sasanian rituals of Zoroastrianism were another important influence. Drawing upon the work of Michael Shenkar, Bonesho notes how important the worship of fire was to the ancient Zoroastrian cult.

In their work, the authors of the Babylonian Talmud collected together some of the traditions about Hanukkah and “reinvented” it as a festival about light and control of light and fire. According to Bonesho, they linked Hanukkah not just to the miracle during the Maccabean revolt, but also to the book of Genesis and the original creation of light. In particular, they connect Hanukkah to a story about the biblical Adam. In a story found in the Babylonian Talmud, Adam grows afraid of the growing darkness that takes place before the solstice. Understandably, Adam is afraid that the light might never return. As the days grow longer after the solstice and the sun returns, he grows increasingly joyful.

Hanukkah Foods

The key ingredient in traditional Hanukkah foods is oil (like the oil used in the lamps). Food made with oil include “latkes” (potato pancakes, often topped with sour cream, cheese, apple sauce or chutney) eaten by Americans and northern and eastern Europeans; “loukamades” (fried cakes dipped in honey and covered in powdered sugar) eaten by Greek Jews; “zelebi” (deep fried spirals of dough and syrup) eaten by Iranian Jews; and “sufganiyot” (jelly donuts) eaten by Israeli Jews.

According to the BBC: “Potato pancakes (latke) and deep-fried doughnuts (sufganiot) are traditional Hanukkah treats. Latke can easily be made at home. A perfectly filled and fried sufganiot is much more difficult. “ Fried food in particular reminds Jews of the miracle of the oil and the candles that burned for eight days after the Maccabees won back the temple in Jerusalem. Dairy products are often eaten during Hanukkah. The tradition has its roots in the story of Judith (Yehudit) who saved her village from the Syrians by making an offering of cheese and wine to the governor of the enemy troops. Judith encouraged the governor to get drunk. After he collapsed on the floor, she beheaded him with his own sword and took his head back to the village in a basket. When the Syrian troops discovered their governor had been beheaded, they fled. [Source: BBC, July 9, 2009 |::|]

Sufganiot—Hanukkah's Donuts

Sufganiot (also spelled sufganiyah, the singular of sufganiyot) is a staple of annual Hanukkah celebrations. Stacey Freed wrote in the Washington Post, “In Israel they're called sufganiot (soof-gan-EE-oat), doughnuts to Americans. But they are more than doughnuts. "The difference is the dough," says Arie "Popi" Eloul, owner of The Kosher Pastry Oven in Wheaton. "The dough we make is like Danish [pastry] dough." Eloul uses cream and rum to create his fried confections — he'll make nearly 10,000 during the week of Hanukkah. Sufganiot are a true Israeli creation. "On the one hand it's one of the oldest 'sweets' known to man, stemming from the Greek loukomades, which are fried and then rolled in honey," says Joan Nathan, author of many books on Jewish cooking. "On the other, it came to Israel with the pioneers from Central and Eastern Europe, who ate their pfannkuchen — doughnuts — filled with apricot and sometimes strawberry jam." [Source: Stacey Freed, Washington Post, December 17, 2003 ||||]

Sufganiot at the Jerusalem central bus station

“The new pioneers, a group that would also include Jews from southern Europe and the Arab world, wanted their own Israeli dish for Hanukkah. "My guess," says Nathan, "is that people like Eliezer Ben Yehuda [credited with the revival of the Hebrew language] looked at this word 'soofgan,' which means 'sponge' in Greek, and gave the name to these fritters." On this side of the Atlantic, sufganiot are traditionally filled with jelly or preserves. But in Israel, where during Hanukkah they are fried and sold on street corners and from mall kiosks, they also come filled with buttercream, chocolate or caramel. Families often make them together at home and eat them after lighting the candles on the menorah each night of the holiday. Eloul, originally a Jerusalemite by way of Morocco, laughs when he says sufganiot are a challenge to make at home and even in the bakery: "It's hard work. Take the oil, the dough, put it here, put it there. I'd rather make a couple of wedding cakes and be happy." ||||

“On the day before Hanukkah, Eloul starts at 3 a.m. mixing the ingredients in a large machine. (This year will be slightly different since Hanukkah begins at sundown on Dec. 19, a Friday, which is the Jewish Sabbath. Eloul will have to make the dough a day in advance.) For each batch he makes about 41/2 pounds of dough, enough for 36 doughnuts. Another machine rolls the dough into "tennis balls." He then puts them in a "proof," a steam box that helps the dough rise, for about 15 minutes. He heats vegetable oil to about 325 to 350 degrees and fries them one side at a time until they have a golden color. A machine injects raspberry jam into the fried dough, and then the doughnuts are powdered with sugar. "You have to eat them the same day," he says. They can be addictive; warm and — although they're fried — soft on the outside and sweet and moist on the inside. "Every year, people are excited. The line we have here. They're yelling at each other. But I just eat the first one to make sure," says Eloul who, like many of us, worries about health and weight. "Otherwise, I don't touch them." ||||

Making Sufganiot

Stacey Freed wrote in the Washington Post: 1) In a small bowl, combine the yeast and 1 tablespoon of the sugar in the warm water. Set aside until foamy, about 10 minutes. 2) In the bowl of a food processor equipped with a steel blade, process the yeast mixture with the flour, milk, whole egg and egg yolk, salt, lemon zest and the remaining 2 tablespoons sugar until blended. Add the butter and process until the dough becomes sticky yet elastic. 3) Shape the dough into a ball, cover and let rise in a warm place until about double in size, at least 1 hour. (If you want to prepare it ahead, loosely cover the dough and refrigerate it overnight, then let it warm to room temperature before rolling and cutting.)

4) Lightly dust the work surface with flour. Roll the dough out to a thickness of 1/2 inch. Using a 2-inch cookie or biscuit cutter or the top of a glass, cut the dough into rounds and roll each round into a ball. Cover and set aside to rise for 30 minutes. 5) Pour enough oil into a heavy pot to reach a depth of at least 2 inches. Heat the oil to 375 degrees. Have ready a plate or baking sheet lined with paper towels. 6) Carefully drop the doughnuts in the oil, 4 or 5 at a time, being careful not to crowd the pan. Fry the doughnuts, turning once, until lightly browned, about 3 minutes per side. Transfer the doughnuts to the lined plate to drain. 7) Using an injector, insert about 1 teaspoon jam into each doughnut. (If using a turkey baster, it will be necessary to first process the jam in a food processor to finely chop any large pieces of fruit. Then insert a thin knife halfway into the doughnut to cut a slit, remove the knife and insert the tip of the turkey baster.) 8) Spread the sugar on a large plate or baking sheet and carefully roll the warm, jelly-filled sufganiot in the sugar. Serve immediately.

Per soufganiot: 173 calories, 3 gm protein, 30 gm carbohydrates, 5 gm fat, 23 mg cholesterol, 2 gm saturated fat, 27 mg sodium, 1 gm dietary fiber. In the beginning, a sufganiot consisted of two rounds of dough sandwiching some jam, but the jam leaked out during the frying. Today, with new injectors on the market, balls of dough can be deep-fried until puffy and then injected with jam.

classic Hanukkah sufganiyot

Sufganiot recipe from The Kosher Pastry Kitchen in Wheaton, Maryland (Makes 18 to 24 doughnuts):

1 package (21/4 teaspoons) active dry yeast

3 tablespoons sugar

1/4 cup lukewarm water

About 3 to 31/2 cups unbleached all-purpose flour, plus additional for rolling

1/2 cup lukewarm milk

1 large egg

1 large egg yolk

Pinch of salt

Grated zest of 1 lemon

31/2 tablespoons butter, at room temperature

Mild vegetable oil, such as canola, for frying

Apricot, strawberry or raspberry preserves for filling

Confectioners' or granulated sugar for rolling

Injector (available at specialty stores) or turkey baster

How Jelly Doughnuts Became a Fixture of Hanukkah in the U.S.

Emelyn Rude wrote in Time: “There’s an Israeli folktale that goes this way: after Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden, God tried to cheer up by giving them jelly doughnuts. Pretty much all scholars agree that the tale has zero basis in the scripture, but the idea that doughnuts bring joy is a standard one across cultures....It’s said that the fried treats are a good fit for a holiday focused on oil, commemorating the miracle of one night of oil lasting for eight. The most stereotypical sufganiyot, after all, are fried balls of yeast dough filled with strawberry jelly and dusted heavily with powdered sugar. But jelly doughnuts weren’t a part of a typical diet at the time the Hanukkah story would have taken place, and the miraculous oil isn’t the whole story behind why they’re eaten on the holiday. [Source: Emelyn Rude, Time, December 8, 2015. Rude is a food historian and the author of “Tastes Like Chicken” (2016) +++]

“The word sufganiyot can be traced back to the Greek word sufan, meaning “spongy” or “fried,” as can the Arabic word for a smaller, deep-fried doughnut named sfenj. This could perhaps be where these treats got their name; similar fried balls of dough have been eaten to commemorate Hanukkah for centuries by Jews in North Africa. But these Moroccan and Algerian treats didn’t have the modern sufganiyot’s characteristic jelly filling, which is where migrants from Central Europe came in. The first fried pastries in European history typically contained savory fillings, like meat or mushrooms. But the establishment of colonies in the Caribbean in the 16th century brought cheap, slave-produced sugar to the continent and led to a renaissance in fruit preserves and from that a renaissance in sweet stuffed pastries. The first known recipe for a jelly doughnut, according to historian Gil Marks, can be found in the 1532 German cookbook Kuchenmeisterei, which translates to “Mastery of the Kitchen” and is remembered by history for being one of the first cookbooks run off of Gutenberg’s famed printing press. The treat was made by packing jam between two round slices of bread and deep-frying the whole thing in lard. +++

“From its Germanic origins, the dessert quickly conquered most of Europe. It became krapfen to the Austrians, the famous Berliners to the Germans and paczki to the Polish. Substituting schmaltz or goose fat for the decidedly un-Kosher lard in their fryers, the Jewish peoples of these regions also enjoyed the dessert, particularly Polish Jews, who called them ponchiks and began eating them regularly on Hanukkah. When these groups migrated to Israel in the early twentieth century, fleeing the harsh anti-Semitism of Europe, they brought their delicious jelly-filled doughnuts with them, where they mingled with the North African fried-dough tradition. +++

coin issued by Mattathias Antigonus

“But it would take more than just the mingling of Jewish cultures to make the sufganiyot the powerful symbol of Israeli Hannukah it is today. Credit must be given to the Israeli Histradut. Founded in 1920 in what was then British-mandated Palestine, the national labor group’s aim was to organize the economic activities of the Jewish workers in the region. Founded on Russian socialist principles, full employment was amongst its aims, as was the integration of the new Jewish immigrants making their ways to the country’s shores. +++

“A perfectly filled and fried sufganiyot is much more difficult. Even some of the most talented at-home cooks will agree that the treat tastes better when left up to the professionals. Which is exactly what the Histadrut wanted: a Hanukkah treat that involved professionals. As many important Jewish holidays are concentrated in autumn, the end of that season often brought a lull in work in Jewish quarters. By pushing the sufganiyot as a symbol of the Festival of Lights, as opposed to the DIY-friendly latke, the Histradut could encourage the creation of more jobs for Jewish workers. +++

“By all accounts, the Histadrut’s efforts to promote the jelly doughnut worked. In modern Israel, over 18 million sufganiyot are consumed in the weeks around the holiday, which averages out to over three doughnuts per citizen. More people enjoy the fried treat than fast on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, and the Israeli Defense Forces purchase more than 50,000 of the doughnuts each day of the eight-day holiday to boost the morale of its troops. Sufganiyot can now be found throughout the United States as well during Hanukkah, produced by Jewish and non-Jewish bakeries alike. After all, as people all over the world have been discovering for centuries, no one can say no to a truly delicious jelly doughnut.” +++

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, Library of Congress, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024