Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut) / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples

ANCIENT EGYPT AND THE BIBLE

Some scholars believe the concept of monotheism dates to Moses time rather than Abraham’s time. Monotheism appeared in Egypt under the pharaoh Akhenaten (1388 B.C. to 1336 B.C.), who lived rough 50 years before the time that Moses is thought to have been alive. Akhenaten attempted to introduce a form of monotheism to ancient Egypt. After his death there was a period of chaos and instability and for a while Egypt was ruled by high priests.

According to the Bible, Joseph and the Israelites were welcomed into Egypt by a pharaoh around the 16th century B.C. after their homeland in Canaan was stricken by drought and famine. Between 1630 and 1521 B.C., Egypt was ruled by the Hyksos, a Semitic people from western Asia. Some scholars have suggested the Hyksos may have included Israelites. Egyptian chronicles later refer to a people called the “Apiru,” which some scholars believe may have included the Hebrews and Israelites.

In Egypt, the Israelites were enslaved, a fate which they endured more than 300 years. The Egyptians "made life bitter for them with harsh labor at mortar and bricks." When the pharaoh viewed the Israelites as a threat he ordered that all male children be killed at birth by throwing them in the Nile. Cuneiform tablets refer ancient nomads for the Near Eat that were put to work building places and temples. Archaeologists believe that the Israelites were include in these nomadic groups.

The 19th Egyptian dynasty was founded in 1335 B.C. at a time when the Egyptian empire was breaking up as result of pressure from the Hittite Empire to the north. Some scholars have suggested that the Israelites may have been enslaved during this period by the Egyptians because they may have presented a threat.

According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: There are close to six dozen agreed upon Egyptian loan words in the Bible, not including personal names and toponyms (place names); some of these words are Hebraized, whereas others are used in forms that are close to their Egyptian form. Understandably, there is a remarkable clustering of these loan words in the biblical accounts relating to Egypt. We have come to expect Egyptian words used to describe the natural environment of Egypt, so the biblical words for "reeds" (Ex. 13:18, 15:4, 22, 23:31; passim), "Nile" (Gen. 41:1–3; passim), "papyrus" (Ex. 2:3; Isa. 18:2, 35:7; Job 8:11), and "marsh grass" (Gen. 41:2, 18; Job 8:11) all are Egyptian loans. The same goes for specifically Egyptian offices like the hartumim typically translated as "magicians" (Gen. 41:8, 24; Ex. 7:11, 22, 8:3, 14–15, 9:11; Dan. 1:20, 2:2, 10, 27, 4:4, 6, 5:11). Pharaoh is a royal title (literally "big house" / "palace") used in the Bible both as a royal title with a specific royal name following (Pharaoh rn – ii Kings 23:29, 33–35; Jer. 46:2), or alone as a virtual royal name or specific appellative (this usage is consistent in the Torah text). Attempts have been made to date biblical passages according to the usage of the word "Pharaoh," but such arguments are speculative at best, and ignore the literary aspects of the text. [Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica, Thomson Gale, 2007]

See Separate Article: HISTORY OF ANCIENT EGYPT AND CANAAN (PALESTINE AND ISRAEL) africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Bible Unearthed” by I. Finkelstein and N. Asher Silberman Amazon.com ;

“Archaeology of the Bible: The Greatest Discoveries From Genesis to the Roman Era”

by Jean-Pierre Isbouts Amazon.com ;

“Where God Came Down” by Joel P. Kramer Amazon.com ;

“Unearthing the Bible: 101 Archaeological Discoveries That Bring the Bible to Life” Amazon.com ;

“Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology: A Book by Book Guide to Archaeological Discoveries Related to the Bible” by J. Randall Price and H. Wayne House Amazon.com ;

“NIV, Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible (Context Changes Everything) by Zondervan, Craig S. Keener Amazon.com ;

“Oxford Companion to the Bible” by Bruce M. Metzger and Michael David Coogan Amazon.com ;

“Historical Atlas of the Holy Lands” by K. Farrington Amazon.com ;

“The Story of the Jews” Volume One: Finding the Words 1000 BC-1492 AD by Simon Schama (Author) Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com ;

“Exodus” by Richard Elliott Friedman Amazon.com ;

"Exodus and Numbers: The Exodus from Egypt" (MacArthur Bible Studies)

by John F. MacArthur Amazon.com ;

"Ramesses II, Egypt's Ultimate Pharaoh" by Peter Brand Amazon.com;

“Pharaoh Triumphant. The Life and Times of Ramesses II” by Kenneth Kitchen (1990) Amazon.com;

“Moses: A Life” by Jonathan Kirsh Amazon.com ;

“Great Lives: Moses: A Man of Selfless Dedication” by Charles R. Swindoll, Maurice England, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Moses: In the Footsteps of the Reluctant Prophet” by Adam Hamilton Amazon.com ;

“Moses and Monotheism” by Sigmund Freud Amazon.com ;

“Gregory of Nyssa: The Life of Moses” (HarperCollins Spiritual Classics Amazon.com ; “Ten Commandments” (film, DVD by

Cecil B. DeMille, with Charleston Heston) Amazon.com ;

“Prince of Egypt” (Dreamworks animation with the voice of Moses supplied by Val Kilmer and his friend Ramses by Ralph Fiennes) Amazon.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

Jews in Egypt

Grace Glueck wrote in the New York Times, “Led by Moses, the Jews fled en masse from Egypt around 1250 B.C., after centuries of bondage. So says the Bible's book of Exodus. But later books — II Kings and Jeremiah — report that 800 years later, during the fifth century B.C., Jews were once again living and worshiping there. The later biblical account was confirmed by the 1893 discovery of hundreds of papyrus scrolls from a settlement on Elephantine Island in the Nile. These scrolls were the centerpiece of a show held at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 2002 called ''Jewish Life in Ancient Egypt: A Family Archive From the Nile Valley.'' [Source: Grace Glueck, New York Times, March 15, 2002]

The scrolls, written in Aramaic, the daily language of Egyptian Jews and Persians, include a marriage contract, a deed of release from slavery, real estate transactions and a loan agreement, but no other objects associated with the family exist. The documents are important in that not only do they confirm the return of Jews to Egypt but also because it points up the good relationships among the various ethnic groups who inhabited the small island. Under the religiously tolerant Persians who ruled Egypt at the time, members of these groups were serving on Elephantine as mercenary forces guarding the country's southern frontier.

Joseph interpreting Pharaoh's dream

Not Ananiah, the scrolls' original owner, however. For 47 years (from 449 to 402 B.C.) he was a member of the Jewish priesthood attached to the Temple of Yahou (Jehovah), where animal sacrifices took place. And what were Jews doing back in Egypt? They were descendants of those who had fled from the Babylonians, who had conquered Jerusalem in 586 B.C. and consigned the Jewish elite to exile in Babylonia. Those who made it to Egypt were the soldiers and common people, who practiced a more rudimentary form of Judaism that still involved the worship of more than one god.

Joseph interpreting Pharaoh's dream Ananiah first comes to notice in a marriage document dated Aug. 9, 449 by the Aramaic calendar, that legalized his union with Tamut, an Egyptian woman whose father had sold her to Meshullam, a not uncommon practice in payment of debts. By the time they got around to wedlock, the couple already had a 6-year-old son, not an unusual circumstance for that time and place. The contract freed their son, Palti, from slavery, but not Tamut.

Written by Aramaic scribes in proper legalese, all the contracts were signed by witnesses, who seemed to have some literacy. Ananiah's wedding contract provided a small dowry from Tamut, including a wool garment worth seven shekels, a mirror, a pair of sandals and six handfuls of castor oil. This civilized document also declared that if Ananiah wanted a divorce, he had to pay Tamut, or vice versa, and that on the death of one, the other inherited their joint property.

Another important scroll, 427 B.C. and signed by Meshullam, releases Tamut and the couple's daughter, Yehoishema, from their bondage to him. ''You are freed to God,'' says the declaration, on the condition that Tamut and her daughter look to the welfare of Meshullam and his son Zakkur for life. In 437 B.C., 12 years after his marriage, Ananiah bought a house from Bagazust, a Persian soldier, and his wife. The rather decrepit property was in a town called Khnum, named for an Egyptian god, right across the street from the temple. The sale is recorded in a third papyrus scroll, assuring clear title to the house, which is described as having a court, standing walls and windows, but no beams.

Four more scrolls are concerned with gifts of various parts of the house to Tamut and Yehoishema by Ananiah, and then the sale of the house, in 402 B.C., to Yehoishema's husband, also named Ananiah. (By this time the house had beams and two doors.) The last of the scrolls, dated 402 B.C., is a receipt for the borrowing of two months' rations of grain by the son-in-law — at no interest, but with a penalty for failure to repay on time — from Pakhnum, an Aramaean. Despite the expulsion of the Persians two years earlier, good business relations apparently continued between Jews and other ethnic groups.

Art with a Jewish connection from ancient Egypt include a quirky sarcophagus lid (664-332 B.C.) topped by an expressive relief face said to be from a Jewish cemetery at Tura, Egypt.

Moses, Exodus and Ancient Egypt

Neither Moses or the Exodus are described in ancient Egyptian records, which are fairly extensive. There are references to “Asiatic” slaves in Egypt that may have been a reference to the Israelites. An Egyptian stele found in 1990 and dated to 1207 B.C., recounting the military victory of Pharaoh Merneptah, says, "Israel is laid waste." But other than that there is little evidence of even the Israelites existing in Moses’s time. No evidence comes from the Israelites themselves because they were a nomadic people with no material culture for archaeologists to dig up In any case the exodus from Egypt was a central event of the Bible. It is referred to not only in the Pentateuch but also in Prophets and the Psalms. Many historians feel that it marked the consolidation of the Hebrew tribes into a single nation and people.

The Exodus — if it happened — is believed to have occurred around 1290 B.C., which roughly corresponds with the era of the Trojan War and the rule of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II. The Exodus was written along with many other parts of the Old Testament in the 7th century B.C. during the reign of King Josiah of Judah.

Was Ramses the Biblical Pharaoh Confronted by Moses

Many scholars believe Ramses the Great (Ramses II, ruled 1279 to 1213 B.C.) was one of the pharaohs described in the story of Moses — either the Pharaoh of the Oppression, who enslaved the Israelites, or the Pharaoh of the Exodus, who pursued them into the sea after the Ten Plagues. In the historical record there is no mention of Israel until the reign of Ramses son and successor Mernetah (ruled 1213–1204). By then Israel was a nation, not a group of displaced people.

Ramses the Great, also known as Ramses II, was perhaps the greatest of all the Egyptian pharaohs. He became Pharaoh in 1279 B.C. when he was in his twenties and the pyramids were already 1,300 years old. He ruled ancient Egypt for 67 years during the golden age of the civilization. He raised more temples, obelisks and colossal monuments that any other Pharaoh and ruled an empire that stretched from present-day Libya and Sudan to Iraq and Turkey. The Bible refers to him simply as "Pharaoh." [Source: Rick Gore, National Geographic, April 1991 [♣]

Some scholars suggest that Ramses II was the builder of the cities of Phithom (Pithom), mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, and Rameses (Pi-Ramesses), but Egyptian sources cannot support this. It is interesting, however, that the only Egyptian reference to Israel occurs in a stele inscription of Ramses II's successor,Merneptah . This stele demonstrates that a people called Israel lived in Palestine at that time, and it was set up to commemorate Merneptah's military victory over Libyans and Sea Peoples (a migratory group from the Near East) in the Delta. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

See Separate Article: RAMSES THE GREAT (RULED 1279 TO 1213 B.C.): HIS FAMILY, ACHIEVEMENTS AND LEADERSHIP africame.factsanddetails.com

Moses's Early Life

Pharaoh's Daughter Receives the Mother of Moses

Pharaoh's Daughter Receives the Mother of Moses According to the Bible and the Torah, Moses was born in Egypt to immigrant parents of the servant: Abraham and Jochebed from the Hebrew Levi tribe. After being hidden for three months, Moses was placed by his mother and sister in "an ark of bulrushes, and dabbed it with slime and pitch" and set afloat on the Nile after the Pharaoh issued an edict declaring all male infants born to Israeli slaves had to be killed.”

Christians and Jews believe Moses was discovered in the bulrushes by the Pharaoh's daughter. Muslims say he was found by the Pharaoh wife. According to the Judeo-Christian story, after being rescued Moses was adopted by the Pharaoh's daughter and was brought up as a prince in the Egyptian royal court where most likely, if the story is based in fact, he would have learned to read hieroglyphics and ride a chariot just as Ramses the Great at King Tutankhamun had. The Bible provides few details. When Moses was a young man he was informed of his true identity by his sister Miriam.

The tale of Moses’ youth resembles old folk stories from ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia and the Middle East. According to an ancient Assyrian narrative about the Mesopotamian king Akkad, who lived a thousand years before Moses, "My priestly mother conceived me, in secret she bore me. She set me in a basket of rushes, with bitumen sealed my lid." In the Egyptian tale of the God Horas his mother Isis hid him from his wicked uncle Seth.

When Moses was three, one episode of his story goes, he snatched the crown off the Pharaoh's head. Dumbfounded, the Pharaoh decided to devise a test to see if Moses realized what he had done. Two plates were placed before the child: one with gold and one with red-hot coals. If he chose the gold one he was to be put to death. If he chose the one with coals he would be spared as "one without knowledge of his acts." Fortunately for him he grabbed the hot one, but unfortunately he stuck it in his mouth and seared his tongue, leaving him with halting speech.”

See Separate Articles: MOSES'S BIRTH, BASKET OF REEDS AND ADOPTION africame.factsanddetails.com MOSES'S EARLY LIFE, FLIGHT FROM EGYPT AND THE BURNING BUSH africame.factsanddetails.com

Moses is Forced to Flee Egypt

Menephthah, the Pharaoh of the Exodus Moses was forced to flee from Egypt to the Sinai when he murdered an Egyptian man who was abusing a Jewish slave. According to the Torah, "And he spied an Egyptian smiting a Hebrew, one of his brethren. And he looked this way and that way, when he saw there was no man, he slew the Egyptian, and hid him in the sand." If he hadn't committed this crime it seems plausible that he would have had a distinguished career in the Pharaoh's court.

Moses fled to a land called Midian, in northwest Arabia, east of the Gulf of Aqaba. While in the desert he met his wife Zipporah, daughter of the Midianite priest Jethro, while she was drawing water from a well. Moses stood up for Jethro when other shepherds tried to shoo him away from the well. For this Jethro offered Moses his daughter. She soon bore Moses a son.

This episode has similarities to a story that circulated in the time of Ramses about a courtier named Sunuhe who fled to the desert and lived with some Bedouins after being blamed for the assassination of a Pharaoh.

Moses returned to Egypt and confronted the Pharaoh: "Thus saith the Lord God of Israel, Let my people go." When Moses first asked the Pharaoh to let his people go the Pharaoh responded by increasing the Israelites work load. Then, not only were they required to make and carry bricks, they also had to raise and harvest straw as binder for the bricks.”

Plagues of Egypt

Death of the Pharaoh's first-born son

Death of the Pharaoh's first-born son When the Pharaoh refused again the Ten Plagues of Egypt were unleashed on the land one after another. In the First the Nile turned to blood, a phenomena some scholars say might have been caused by red mud pouring down the river from Ethiopia. The plagues of frogs, lice, flies, cattle disease and bolis that followed, they say, are conditions usually associated with seasonal floods. The seventh plague, hail and fire, may have been a hailstorm with lightning or a volcanic eruption in the Mediterranean. The eight plague, locusts, still swarm from time to time. The three days of darkness that followed may have been a sandstorm.

In the tenth plague the firstborn of every Egyptian family was killed, even the pharaoh's oldest son. Exodus 12:29 in the Bible reads: "at midnight the Lord smote all the firstborn of the land of Egypt, from the firstborn of the Pharaoh that sat on his throne unto the firstborn of the captive that was in the dungeon." Historians have yet to find any evidence of this event.

Finally after the tenth plague the Pharaoh at last let Moses and the Israelites go. Before the plague struck Israelites were told to sacrifice a lamb and paint their doorways with its blood. Their homes were passed over by the plague, which is the origin of the Passover holiday. During Passover, Jews eat unleavened bread or matzo. The explanation for this tradition is that the Jews were forced to pack up and leave Egypt so quickly they didn't have time to leaven their bread.”

See Separate Article: MOSES, MAGICIANS, PLAGUES AND "LET MY PEOPLE GO" africame.factsanddetails.com PLAGUES OF EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Moses and the Exodus

After the 10th plague and the observation of the first Passover, Moses and the Israelites embarked on their Exodus from the Land of Goshen in the Nile Delta in Egypt to the Promised Land. The Israelites at first were reluctant to have Moses lead them. There is little evidence of the Exodus. There are accounts of Egyptian raids into Palestine that brought back captives in the 12th century B.C. but there was no record of huge masses of people escaping and crossing the Sinai.

According to the Bible, the Israelites numbered some 600,000 adult males and their families: perhaps two million people. That is an awful lot of people to wandering around a desert with barely enough food to feed goats and Bedouins. Some scholar believe the 600,000 figures was actually taken from a census in Israel centuries later. Other scholars say the Hebrew word eleph which translate to thousand, may in fact mean "family." Some 600 families, with about a total of 1,500 people, seems like a more reasonable number.”

The route between Goshen in the Nile Delta in Egypt and the Promised Land in Canaan (Israel) crossed the Sinai Peninsula. Some scholars believe that Moses followed a northern route across the Sinai. Other say he took a southern route. Both point to the miracles of manna and quails to back up their argument.

Most of the geographic location described on the Books of Exodus through Deuteronomy are impossible to locate on a map. The journey began on the Nile Delta and ended on Mount Nebo in Jordan, a distance roughly equivalent to the distance between New York and Washington D.C.”

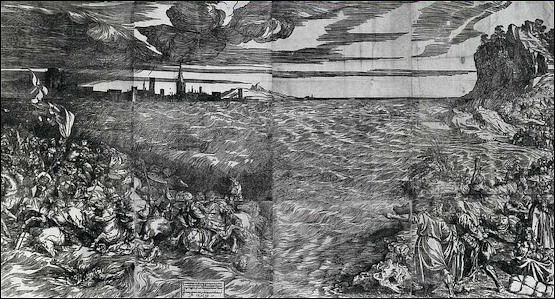

Pharaoh pursues the Israelites

Most scholars believe that if the Exodus indeed took place the Israelites left the Nile Delta and entered the Sinai where the Suez Canal is today, which completely bypasses the Red Sea. Kadesh-barnes, where the Israelites stopped for 38 years before entering the Promised Land, is thought to be the oasis of Ayn al Qudayrat, near the Israeli city of Beersheba.

There are four major routes between Goshen and Kadesh-barnes. The Northern routes passes through a Sea of Reeds in the Mediterranean. The other three pass through a Sea of Reeds near the present-day Suez Canal. Of these, one route reaches southern Sinai while the other two pass through the center of the Sinai. From Kadesh-Barnea to Mt. Nebo the are two major routes

Proponents of the southern route theory say after skirting the Red Sea, the Israelites headed southeast to Great Bitter Lake and Little Bitter Lake, which are full of reeds and equated with the "Reed Sea." Mt. Sinai, where Moses received the Ten Commandments, is believed to be a 7,497-foot purple granite peak long called Gebel in the southern Sinai.

See Separate Articles: THE EXODUS: MOSES, ROUTES, EVENTS AND MANNA africame.factsanddetails.com ; PARTING OF THE RED SEA AND POSSIBLE EXPLANATIONS FOR IT africame.factsanddetails.com

Moses and the Parting of the Red Sea

Menephthah, the Pharaoh of the Exodus?

After the Israelites left Egypt the Pharaoh changed his mind about letting the Israelites go and sent an army in pursuit of them and cornered them at the Red Sea. To allow the Israelites to escape Moses parted the Red Sea. According to the Torah, "And the Israelites went into the sea on dry ground, the waters forming a wall for them on the right and on their left." When the Egyptian chariots pursued them the waters of the Red Sea collapsed and drowned them.

To explain the parting of the Red Sea some scientists suggest that Moses passed through the swampy region near where the Suez Canal is today. They speculate that if Moses arrived at a time when a strong low tide coincided with strong winds the Red Sea might "part" enough to be crossed on foot. When the Egyptians crossed the tides ebbed and winds died, swamping the pursuers.

Adding further credence to this theory is the fact that the Hebrew phrase, Yam Suph , traditionally translated to "Red Sea," should actually be read as "Reed Sea." The Bitter Lakes, Lake Sirbonis (a Mediterranean lagoon now called Sabkhet el Bardowil) and Lake Manzala, where the water is shallow enough to be crossed on foot, both have lots of reeds.”

The victory song sung after a defeat of the Egyptian cavalry resembled Canaanite poems from the 14th century B.C.

Lack of Evidence of Exodus

For nearly a century, historians have argued about whether or not the events in Exodus actually took place. There is little evidence that it. This then begs the question: Why does the Hebrew Bible make such as big deal about the oppression of the Israelites by Egypt when there is so little evidence for their enslavement there?

The Ipuwer Papyrus is an ancient Egyptian hieratic papyrus made during the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, whose original composition is dated no earlier than the late Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt (c.1991-1803 B.C.). In a poem, Ipuwer – a name typical of the period 1850-1450 B.C. – complains that the world has been turned upside-down. For a time this poem was offered as evidence of The Exodus from the Old Testament, most notably because of its statement that "the river is blood" and its frequent references to servants running away. The archeological evidence however does not support the story of the Exodus, and most histories of ancient Israel no longer consider it relevant. Many texts in the Ipuwer Papyrus contradicts Exodus story, such as the fact that its Asiatics are arriving in Egypt rather than leaving, and the likelihood that the "river is blood" phrase may refer to the red sediment colouring the Nile during disastrous floods, or may simply be a poetic image of turmoil. [Source: Wikipedia]

Candida Moss of the University of Birmingham wrote in The Daily Beast, “Scholars have been skeptical about the historicity of the Exodus for over 70 years. In the first place the Egyptians, who were fairly remarkable record keepers, never refer to a mass exodus of slaves or even a large group of runaway slaves. To this we might add the lack of evidence for either a slaughter of Hebrew infant boys or the 10 plagues that befell the Egyptian people (during which the eldest son of every Egyptian family dies overnight). There’s also no mention of Moses, even though his name is Egyptian in origin. Finally there’s no archaeological evidence to support the idea of a mass exodus of people. When large groups of people traveled in the pre-eco-friendly age they left behind trash, and a lot of it. But there’s no archaeological evidence for mass migration from Egypt to Israel: no pottery shards or Hebrew carvings. [Source: Candida Moss, The Daily Beast, July 31, 2016 \~]

“All of which is to say that if there was a historical enslavement in and subsequent exodus from Egypt it is highly unlikely that it was on the scale of the Biblical account. Perhaps small groups escaped slavery and came to the land that would become Israel, but certainly not 600,000 men (plus wives and children). Modern scholars like David Wolpe have been strongly attacked for making this argument, but, as Wolpe himself notes, this evidence doesn’t negate the claims of modern Jews to the land of Israel.” \~\

See Separate Article: HISTORICAL EVIDENCE OF MOSES, THE EXODUS AND THE EARLY JEWS? africame.factsanddetails.com

Egyptians, the Great Biblical Villains?

Candida Moss of the University of Birmingham wrote in The Daily Beast, “When it comes to the prototypical villains of ancient literature, the Egyptians are right up there. Nobody, it seemed, really liked the ancient superpower. Ancient Greek romance novels routinely portray them as cunning and duplicitous. The Romans found Cleopatra to be equal parts captivating and conniving and, in the Bible, the Israelites were enslaved by the Pharaohs for centuries. [Source: Candida Moss, The Daily Beast, July 31, 2016 \~]

“The story, as told in the book of Exodus and Prince of Egypt, is that the Israelites came to Egypt because of famine. They initially prospered (think Joseph and his technicolor dreamcoat) only to be enslaved by later generations of Egyptians. There they remained until the birth of Moses, the 10 plagues, and the eventual emancipation of the Hebrews. \~\

“But it does raise an interesting historical question: If the Exodus didn’t take place on an epic Charlton Heston scale, how does Egyptian oppression come to feature so prominently in the biblical narrative? When the story of the exodus was written down in the first millennium, the Israelites wouldn’t have had any direct experience of Egyptian power for hundreds of years; in the meantime, the great empires of Assyria and Babylonia had come to power, drastically overshadowing any threat from Egypt. Why make the Egyptians the villains of the piece? \~\

“Perhaps the biblical description of dominance by Egyptians actually has very little to do with enslavement and more to do with the cultural memory of the more distant Amarna period in Canaan. The Israelites were never subject to national enslavement in Egypt; but, as this new discovery reminds us, the land of Canaan was under the foot of Pharaonic authority. The long shadows of that experience might help explain why—in the absence of a historical Exodus—the biblical authors made the Egyptians the villains of their national epic.” \~\

Pharaoh pursues the Israelites

Evidence of Egyptian Villainy in Canaan?

A new find in Israel reported in 2016 may shed some light on the relationship between the ancient Egyptians and ancient Hebrews. Candida Moss wrote in The Daily Beast, “A new discovery at Tel Hazor, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the largest Biblical-era archaeological sites in Israel, may change how we think about the Egyptians. During excavations, archeologists discovered a 4,000-year-old fragment of a large limestone statue of an Egyptian official. Only the lower section of the statue survives, but it includes the official’s foot and a few lines in Egyptian hieroglyphic script. [Source: Candida Moss, The Daily Beast, July 31, 2016 \~]

“The preliminary study of the artifact has not yet been completed, so archaeologists do not even know the official’s name. Professor Amnon Ben-Tor of Hebrew University’s Institute of Archaeology, who has worked at the site for over 27 years, told the Jerusalem Post that it is likely that the statue was originally placed at the official’s tomb or in a temple. \~\

“So far Tel Hazor is the only archaeological site in the Levant to have yielded any large Egyptian statues from the second millennium B.C.. The only other is a sphinx fragment of the Egyptian Pharaoh Menkaure (known to the Greeks as Mycerinus) that dates to the 25th century B.C.. In the Amarna period—a period of Egyptian history when the royal residence shifted to Akhetaten and Egyptian religion temporarily shifted towards monotheistic worship of the sun god Aten—most of Canaan (what would later be Israel) was under Egyptian control. The latest finds are especially interesting because historians were unaware that Hazor was one of the Egyptian strongholds in this period or that there was ever an Egyptian official there.”\~\

History of Ancient Egypt-Palestine Scholarship and the Unreliability of the Bible Susan Cohen of Montana State University wrote: “Egyptology and ancient Near Eastern archaeology —in the nineteenth century, scholarship of the relationship between Egypt and the southern Levant relied heavily on the history of, and relationships between , the regions as presented in the biblical text. Likewise, early scholarship in both Egyptology and southern Levantine archaeology placed considerable emphasis on Egyptian historical sources, stemming partly from a disciplinary bias toward written text but also, and in large part, due to the relative dearth of archaeological data to support, supplement, or refute these written data. This rather uncritical approach to issues of historicity in both biblical and Egyptological tex ts strongly influenced views of Egyptian-Palestinian interactions well into the middle of the twentieth century, and in some cases, even later. [Source: Susan Cohen, Montana State University , 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Only in the latter part of the twentieth century, with the separation of Syro-Palestinian archaeology from “biblical archaeology” and the increasing amount of field excavation in both regions, was emphasis on biblical material and written source tempered by and/or augmented with more archaeological data and critical perspectives, which enabled Palestinian-Egyptian relations to be viewed through something othe r than either biblical lens or pharaonic hubris. The development of increasingly sophisticated archaeological methodologies and theoretical approaches, ceramic typologies, and other technological advancements al lowed for the historical and biblical material to be examined in conjunction with evidence provided by excavation and accompanying analysis of material remains.

“Thus, as excavation at the important sites of, for example, Tell el-Dabaa, Jericho, Samaria, and Gezer increasingly revealed the unreliability of biblical material regarding such key Egyptian-Palestinian events as the sojourn of Israel in Egypt, the Exodus, and the international relationships of the Israelite kingdoms, it simultaneously demonstrated the complexity, nuance, and richness of the relationships between inhabitants of the southern Levant and Egypt and the myriad ways in which these individuals and regions interacted.”

Drowning of the Pharaohs Host in the Red Sea

Ancient Egyptian Stories with Parallels in the Bible

“Egypt plays an important part in the narrative setting of the Torah. From the time that Joseph is sold into servitude through the Exodus and the crossing of the Sea of Reeds, the central location of the story is Egypt. It is in these stories, the ones set in Egypt, that the majority of narrative parallels are to be found. The most frequently cited example is the biblical tale of Joseph and Potiphar's wife (Gen 39) and the New Kingdom Tale of Two Brothers. The Egyptian tale is the first known example in ancient literature of the Temptress motif. The details and purposes of each of the stories differ greatly, but there is no serious doubt that the structure of the motif is essentially the same. In such stories an older woman (or a woman of higher social status) develops an ill-advised passion for a younger man (or one of a lesser social status). This "temptress" makes her desires known to the young man (Gen 39:7) who refuses her advances on moral grounds (verses 8–9); thus spurned, the "temptress" accuses the young man of violating her, and the "wronged" husband then seeks retribution. The standard versions of this tale eventually vindicate the youth and punish the mendacious wife. In the biblical account Joseph is punished for his supposed actions by being imprisoned (verses 19–20). Eventually he is pardoned by Pharaoh and released from prison because, after interpreting Pharaoh's dreams, Joseph is rewarded and made viceroy of Egypt (41:14–45). The biblical version deviates from the pattern in two significant ways: First, the narrator never tells us that Joseph is ever publicly declared innocent. (He is pardoned not exonerated). Second, the fate of the temptress is not revealed. Potiphar's wife disappears from the story right after she accuses Joseph (Gen 39:18–19), because she is no longer important to the progress of the narrative. [Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica, Thomson Gale, 2007]

“Although the Tale of Two Brothers is the most frequently cited example of biblical and Egyptian narrative parallels, it is by no means the only one. Some literary tales present us with a picture of Syria-Palestine that is reminiscent of the description of the area in the Patriarchal Narratives of Genesis and also show some parallel values. The prime example is the Middle Kingdom Tale of Sinuhe, which depicts the environment of the Levant in detail and shows it much the same as described in the Torah narratives. Both the Hebrew and Egyptian sources describe pastoral nomadic clans who travel among the settled urban population centers. Sinuhe was an attendant to Princess Nefru, daughter of Amenemhet i and wife of Sesostris i. After Amenemhet i dies, Sinuhe overhears plans for a palace coup. Fearing that he will be caught up in the civil-war that will inevitably follow, he flees Egypt and wanders through the Nile Delta and throughout Canaan. Sinhue becomes very successful in Canaan, but always longs to return to his native land. Ultimately, he is reunited with Sesostris i and urged to return to Egypt. As with most Egyptian tales, this one ends happily when Sinhue returns to Egypt and is welcomed back into the royal household, His wish that he be allowed to returned to Egypt so he may die and be buried there is fulfilled. Sinuhe's flight from political danger may be compared to Moses' flight from Egypt to avoid Pharaoh's wrath (Ex. 2:15). Sinuhe's subsequent wanderings though the Egyptian Delta and into Canaan along with his new found prosperity in a foreign land may be compared with the accounts of Abraham's peregrinations. Another frequently cited parallel is that Sinuhe very much wants to be buried in his native Egypt, just as Jacob desires that his body be returned from Egypt to Canaan (Gen. 47:29–30). Similarly, Joseph adjures the children of Israel to carry his bones out from Egypt when they leave (Gen 50:25, Ex. 13:19).

“Narrative parallels are not limited to the Torah. One of Sinuhe's exploits has been compared to David's slaying of Goliath. "He came toward me while I waited, having placed myself near him. Every heart burned for me; the women jabbered. All hearts ached for me thinking: 'Is there another champion who could fight him?' He [raised] his battle-axe and shield, while his armful of missiles fell toward me. When I had made his weapons attack me, I let his arrows pass me by without effect, one following the other. Then, when he charged me, I shot him, my arrow sticking in his neck. He screamed; he fell on his nose; I slew him with his axe. I raised my war cry over his back, while every Asiatic shouted. I gave praise to Mont, while his people mourned him" (Lichtheim in cos) Both Sinuhe and David are underdog warriors who surprisingly vanquish the enemy champion with his own weapon (i Sam 17:51).

Ancient Egyptian Hymns, the Psalms and Proverbs

According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: “Scholarly consensus recognizes that the biblical Wisdom tradition, and much of the poetic and instructional literature related to that tradition, has very close associations with Egyptian Wisdom Literature. Within the Bible there is a conception of Egypt as a source of great wisdom (i Kings 4:30, "Solomon's wisdom was greater than the wisdom of all the Kedemites and than all the wisdom of the Egyptians"), but this "wisdom" is not that of the Wisdom Literature. Egyptian Wisdom Literature deals with "truth," "justice," and especially "order," the "cosmic order" as ordained by the gods. Biblical Wisdom focuses primarily upon Wisdom personified and the "fear of God" associated with it. So the larger conceptions that inform the genre are not identical, but the Egyptian material most certainly has influenced the biblical. [Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica, Thomson Gale, 2007]

“Psalm 104 is frequently viewed in light of "The Great Hymn to the Aten." Both texts venerate the solar aspects of the deity and use similar language in so doing. Song of Songs is widely recognized as having significant parallels to Egyptian love poetry (Fox) There are parallels of phraseology: In the Song of Songs "sister" is used as a term of intimacy between the two lovers (4:9, 10–12, "…my sister, my bride…"; also 5:1, 2), and in the Egyptian Love Songs both "sister" and "brother" are used as terms of love and intimacy. In both literatures there is an alternation between the speech of the girl and that of the boy, but with a difference; In the Bible the lovers engage in dialogues, whereas in the Love Songs from Egypt the lovers are given alternating soliloquies. Another common feature is found in the so-called "Praise Song," where the physical beauty of the beloved body is described limb by limb. (4:1–7; 5:10–16; 7:2–10a).

“Even more striking parallels are to be found in instructional literature; these connections were first recognized in the early 20th century, and are regularly noted in modern commentaries. The prime example is the "Instruction of Amenemope." Proverbs 22:17–24:22 and Jeremiah 17:5–8 are both thought to be inspired by "Amenemope." Of particular interest is Proverbs 22:20 and the difficulty surrounding the Hebrew word traditionally written both shlshwm (ketiv) and shlyshym (qere) and vocalized to mean either "officers" or "the day before yesterday." Neither makes any sense in the context of the pericope. Accordingly, many scholars vocalize this word as sheloshim, "thirty" ("Have I not written for you thirty sayings of counsel and wisdom") especially since there are 30 chapters in the "Instruction of Amenemope" and that text ends "Look to these thirty chapters, They inform, they educate …."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024