Home | Category: Late Stone Age and Copper and Bronze Age / New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut) / Moses / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples / Moses / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples

HISTORY OF ANCIENT EGYPT AND PALESTINE

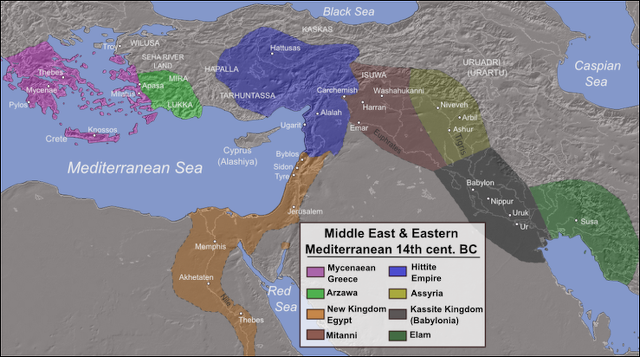

Susan Cohen of Montana State University wrote: “Egyptian interactions and contact with Palestine began as early as the fourth millennium BCE, and continued, in varying forms and at times far more intensively than others, until the conquest of the ancient world by Alexander the Great. Numerous data—textual, material, archaeological—found in both Egyptian and southern Levantine contexts illustrate the diverse spectrum of interaction and contact between the two regions, which ranged from colonialism, to imperial expansion, to diplomatic relations, to commerce. By virtue of geographic proximity, economic interests, and occasionally political necessity, the respective histories of the two regions remained irreducibly interconnected. In all periods, situations and events in Egypt influenced growth and development in the southern Levant, while at times different societies and political considerations in Palestine also affected Egyptian culture. [Source: Susan Cohen, Montana State University, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Egyptian texts thus often remains uncertain; this imprecision has ramifications for understanding the relationship between Egypt and Palestine, a problem which is then further compounded by difficulties in establishing clear chronological synchronisms between the two regions, particularly in the earlier eras. In general, synchronisms between the Egyptian Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods and the Palestinian Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age I are fairly well established. However, recent 14C analyses have resulted in significant changes in the chronological synchronisms between Old Kingdom Egypt and the Palestinian Early Bronze Age. These new data clearly indicate that, rather than being coterminous with the Palestinian Early Bronze Age III, much of the Old Kingdom was contemporary with the relatively deurbanized period of the Intermediate Bronze Age, which clearly has significant repercussions for under-standing Egyptian-Palest inian interactions in the third millennium.

“Likewise, the chronological synchronisms for the first half of the second millennium are in flux. Recent studies suggest that the earliest rulers of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom were contemporary with the Palesti nian Intermediate Bronze Age, whereas the Middle Bronze Age proper corresponds to the mature Middle Kingdom (starting with the reign of Amenemhat II) and later. Finally, recent C14 analyses also indicate that the absolute dates for the transition to the Palestinian Late Bronze Age must be raised by almost a century from those in conventional usage, thereby affecting understandings of the relationship betw een New Kingdom Egypt and the southern Levant in the Late Bronze Age.

“Fortunately, relationships and chronologies become more straightforward in the latter centuries of the second millennium, and continuing into the first millennium through the beginning of the Hellenistic Period. While questions remain regarding precise dates and individual events, the general correlations between the later periods in Egypt and the Iron Age I-II and Persian periods in Palestine are relatively well established.

“Egypt Palestine Approximate Dates: Predynastic Badarian Naqada I Naqada II (early) Chalcolithic – Early Bronze Age IA 4500 – 3300 BCE Predynastic Naqada II (late), III Early Dynastic Dynasty 0 Early Bronze Age IB 3300 – 3200/2900 BCE Early Dynastic Dynasty I Dynasty II Early Bronze Age II – Early Bronze Age III 3200/2900 – 2650/2500 BCE Old Kingdom Dynasty III Dynasty IV Dynasty V Dynasty VI Intermediate Bronze Age 2650/2500 – 2160 BCE First Intermediate Period Dynasties VII – XI Intermediate Bronze Age 2160 – 2055 BCE Middle Kingdom Dynasty XI Dynasty XII Dynasty XIII Dynasty IV Intermediate Bronze Age – Middle Bronze Age I – Middle Bronze Age II (early) 2055 – 1773/1650 BCE Second Intermediate Period Dynasties XV-XVII Middle Bronze Age II (late) 1650 – 1550 BCE New Kingdom Dynasty XVIII Dynasty XIX Dynasty XX Late Bronze Age I – Iron Age IB 1550 – 1069 BCE Third Intermediate Period Dynasties XXI – XXV Iron Age IB – Iron Age IIB 1069 – 664 BCE Late Period – Persian Period Dynasties XXVI – XXX Iron Age IIC – Babylonian destruction – Persian Period 664 – 332 BCE”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times” by Donald Redford Amazon.com ;

“Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, Philistines, and Early Israel, 1300-1100 B.C.E.” by Ann E Killebrew Amazon.com;

“When Egypt Ruled the East” by George Steindorff and Keith C. Seele (1963) Amazon.com;

“Canaan and Canaanite in Ancient Egypt” by Alessandra Nibbi (1989) Amazon.com;

“The Battles of Armageddon: Megiddo and the Jezreel Valley from the Bronze Age to the Nuclear Age” by Eric H. Cline (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Dawn of Israel: A History of Canaan in the Second Millennium BCE”

by Lester L. Grabbe Amazon.com ;

“The Canaanites: Their History and Culture from Texts and Artifacts” by Mary Ellen Buck

Amazon.com ;

“Israelite Religions: An Archaeological and Biblical Survey”

by Richard S. Hess Amazon.com ;

“Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan” by John Day , Andrew Mein, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Stories from Ancient Canaan” by Michael D. Coogan and Mark S. Smith Amazon.com ;

“Hazor: Canaanite Metropolis:Israelite City” by Amnon Ben-Tor Amazon.com ;

“The Bible Unearthed” by I. Finkelstein and N. Asher Silberman Amazon.com ;

“Archaeology of the Bible: The Greatest Discoveries From Genesis to the Roman Era”

by Jean-Pierre Isbouts Amazon.com ;

“Unearthing the Bible: 101 Archaeological Discoveries That Bring the Bible to Life” Amazon.com ;

“Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology: A Book by Book Guide to Archaeological Discoveries Related to the Bible” by J. Randall Price and H. Wayne House Amazon.com ;

“NIV, Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible (Context Changes Everything) by Zondervan, Craig S. Keener Amazon.com ;

Egypt, Palestine, Trade, Migration, Control and Conquest

Susan Cohen of Montana State University wrote: “In all periods, peoples moved between the regions of Egypt and the southern Levant, transpor ting goods and resources (which included people as well). From Palestine, Egypt imported oil, wine, bitumen, and other materials, and from Sinai, copper and turquoise; in turn, Egyptian goods such as gold, glass, beads and other jewelry, palettes, and alab aster vessels, among other items, were exported in varying quantities and with varying frequencies to Palestine. While the intensity and nature of Egyptian contact with the southern Levant varied over time, there was rarely a period in which there was not some interaction between the regions, and this close connection had a significant effect on both.

“In the southern Levant, whether through intensive or sporadic commercial activities, imperial control, settlement, or other means, development remained linked to the presence, absence, and actions of Egypt, even during the eras in which Egypt itself experienced decentralization and/or decline in organization and power. In addition to the more visible manifestations of influence present in the ceramics, other ma terial culture, and architecture found at sites throughout the southern Levant in different periods, Egypt also affected the nature and direction of Palestinian social, economic, and political organization, and significantly, in the late Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period, Egypt also influenced the development of the Canaanite alphabetic script. For Palestine, Egypt loomed as a presence neither to be discounted nor ignored, and any interpretation of Palestinian development in the eras preceding the conquest by Alexander the Great must take this into account.

“From the Egyptian perspective, however, Palestine played different roles at different times. While stereotypical language and conventional image ry portrayed the southern Levant as a region inhabited by “wretched” Asiatics, destined to be crushed and subjugated as part of Pharaonic might and right, Egyptian-Palestinian contact was both far more variable and considerably more realistic. In some eras, such as the Early Dynastic Period and the bulk of the New Kingdom, the southern Levant clearly formed part of a greater Egyptian hegemony and was viewed by Egypt as such. By contrast, in the Late Period, Palestine served as a buffer zone between Egypt and other great powers of the ancient world. At yet other times, such as during the Old and Middle Kingdoms, it is clear that the southern Levant was not the primary target of Egyptian focus and interest, leaving Palestine to develop and function at the margin of Egyptian concerns. Accordingly, the Egyptian views, descriptions, and presentations of Palestine and its inhabitants differ significantly over time, as does the nature of evidence that illustrates these interactions. Yet, just as Palestinian history wa s swayed by Egyptian actions, the southern Levant too contributed to the policies, fortunes, and history of Egypt—as region of settlement, trading partner, real and idealized enemy, buffer zone, and subject territory.”

Egypt and Palestine in the Predynastic and Early Dynastic Periods

Susan Cohen of Montana State University wrote: “Egypt’s contact with Palestine began during the fourth millennium BCE, during the Badarian and Naqada I phases, corresponding to the Palestinian Chalcolithic Period and Early Bronze Age IA. This contact — most probably of a commercial nature —is illustrated by Palestinian ceramics found in Egypt at such sites as Maadi and Minshat Abu Omar, amo ng others. Likewise, a limited amount of Egyptian material is found in the southern Levant. [Source: Susan Cohen, Montana State University , 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Egyptian-Palestinian interaction intensified during Egypt’s Naqada II-III, corresponding to the Early Bronze Age IB in the southern Levant, and reached its apex in Dynasty I. During this time, large quantities of Egyptian and Egyptianizing material are attested throughout southern Palestine , at sites such as En Besor, Tel Erani, Nahal Tillah, and Tell el-Sakan. In addition to the extremely large volume of ceramics, much of which is of a rather prosaic nature, mud sealings at En Besor and serekhs (early representations o f the king’s name in hieroglyphs enclosed within a diagram of the palace gateway and usually surmounted by an image of the Horus falcon) of various Early Dynastic pharaohs excavated at the sites of Arad, Tel Erani, Tel Halif, and Tell el-Sakan, among others, attest to an active Egyptian presence in the southwestern southern Levant. In addition, evidence for an Egyptian flint industry in Palestine has been no ted at En Besor and Tel Erani.

“The vast quantities of Egyptian material found at sites throughout southern Palestine point to an active and flourishing interaction between regions. The utilitarian aspect of the Egyptian ceramics —used for cooking, baking, etc., rather than as containers for “luxury” goods —suggests the existence of a resident Egyptian population in southern Palestine during this period. This phenomenon has been interpreted by some scholars as illustrative of an Egyptian colonial presence, and by others as representative of a more commercial relationship. Regardless of precise interpretation, all evidence indicates that southern Palestine was strongly influenced by Egypt during this period, p erhaps stemming from Egyptian policies of, and efforts toward, resource acquisition and control.”

Egypt and Palestine in the Old Kingdom (2649–2150 B.C.)

Susan Cohen of Montana State University wrote: “Following the intensive Egyptian presence in the Predynastic Period, Egyptian interests in Palestine steadily declined, starting in mid-Dynasty II and continuing through the Old Kingdom, corresponding to Palestinian Early Bronze Age II through Early Bronze Age III, into the Intermediate Bronze Age. This change is marked by a corresponding decrease in the amount of Egyptian materials found in the southern Levant. [Source: Susan Cohen, Montana State University , 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Such materials as do exist, such as palettes and other small items, are indicative of small-scale exchange and movement of smaller luxury goods. Old Kingdom activities instead focused primarily on exploitation of copper and other resources in Sinai. Overall, the Egyptian commercial and military presence in Palestine remained minimal during the Old Kingdom; the former is illustrated by the decrease in qu antity, quality, and distribution of materials, and the only evidence for the latter derives from the isolated campaign mentioned in the Egyptian Tale of Weni .

“The minimal Egyptian interest and activities in the southern Levant d uring the Old Kingdom continued into the First Intermediate Period, contemporary with the latter part of the Intermediate Bronze Age. There is little evidence for Egyptian activity in Palestine proper, and Egyptian direct control over mining in Sinai—which flourished under Old Kingdom rule —also declined. This may have allowed for increased Palestinian participation in the copper and turquoise mining and transport previously monopolized by Egypt; the increase in settlement in Sinai and the northern Negev may be linked to this phenomenon in the later part of the Intermediate Bronze Age, although establishing precise dates or phases for the sites remains difficult.”

Egypt and Palestine in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.)

Susan Cohen of Montana State University wrote: “Following the reestablishment of centralized rule at the end of the 11 th Dynasty, Egyptian activity in the southern Levant increased during the Middle Kingdom, although the means and intensity of contact remained variable. Evidence for Egyptian interaction with Palestine derives from multiple sources, some of which are difficult to contextualize. The Egyptian textual data include the Execration Texts, which list a series of locations and individuals to be magically subdued; while these imply an Egyptian knowledge of both Palestinian geography and current events, they are of uncertain use in determining the scope and type of Egyptian activity in the region. Likewise, Khu-sobek’s account of Senusret III’s campaign to a location traditionally identifie d as Shechem in northern Palestine, while indicative of bellicose relations, appears to represent an isolated campaign. [Source: Susan Cohen, Montana State University , 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The limited volume of Egyptian ceramics found at Ashkelon and Tel If shar, as well as a collection of approximately 40 mud sealings found at the former site, however, suggests economic ties between the two regions. Taken together , this evidence presents a picture of variable and sporadic Egyptian contact with Palestine, consisting of minor military actions combined with small-scale commercial contact. Overall, regardless of type, Egyptian contact with Palestine remained both minimal and sporadic during the Middle Kingdom.

“As Egypt entered a second phase of decentralization in the Second Intermediate Period, its relationship with the southern Levant again changed accordingly. Egyptian activit ies in Palestine —already sporadic and variable in the preceding Middle Kingdom — decreased still further. Likewise, as the urban centers in Palestine gained in strength and power, southern Levantine cultural influence extended further into Egypt. Excavation at Egyptian sites such as Tell el-Dabaa (ancient Avaris) clearly illustrates influence from the southern Levant in ceramics and other material culture, as well as in local cult and ritual, while it also demonstrates the development of a hybridized cultural corpus. In turn, Egyptian-Hyksos scarabs are found at sites throughout the southern Levant, although, to date, there is a dearth of Egyptian and/or Hyksos ceramics found in Palestine at this time.”

Egypt and Palestine in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.) and Afterwards

Susan Cohen of Montana State University wrote: “The rise of the New Kingdom in the latter part of the second millennium BCE saw the establishment of an Egyptian Levantine empire that included not only the southern Levant but extended throughout the eastern Mediter-ranean world into the northern Levant. Contemporary with the Palestinian Late Bronze Age and Iron Age I, Egyptian imperial power steadily increased during the first several reigns of the New Kingdom. Egyptian political control of Palestine, and the accompanying influence on social and c ultural development, are clearly reflected in Egyptian-style architecture, including temples and forts, found at sites s uch as Beth Shean, Deir el-Balah, and Tel Mor. Sizable corpora of ceramics and other material cul ture found throughout Palestine clearly reflect either Egyptian origin or Egyptian influence and make up a large percentage of the material culture remains . In addition, anthropoid coffins found at Deir el-Balah and Tell el-Farah (South) also help to illustrate the Egyptian influence in the southern Levant. [Source: Susan Cohen, Montana State University , 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The textual data and historical records from New Kingdom Egypt also reveal the strong scope of Egyptian activities in Palestine, as well as in surrounding reg ions in the eastern Mediterranean. For example, among the myriad Egyptian texts from this period, Thutmose III’s account of his Megiddo campaign and the Amarna Letters from the reigns of Amenhotep III and Amenhotep IV/Akhenaten illustrate the imperial nature of Egyptian activity in the southern Levant from the early New Kingdom through the Amarna Period; the latter texts also provide a wealth of information regarding settlement and political organization in the southern Levant, as well as details regarding Palestinian interaction with Egypt.

“During the later New Kingdom, beginning in the 20th Dynasty, Egypt experienced the slow decline of its Levantine empire —part of the upheaval noted throughout the Mediterranean world at this time. The disruption of Egyptian hegemony in Palestine may perhaps be traced to the arrival of the Sea People s, and Egypt’s encounters with them, during the reigns of Merenptah and Ramesses III. The decline in the Egyptian empire in the southern Levant attested by historical sources is matched by a slow but measureable decline in the extent and number of Egyptian artifacts found in Palestinian contexts post-Dynasty XX.

“Little data exist for Egyptian activity in Palestine during the Third Intermediate Period, corresponding to late Iron Age I through Iron IIA-B. Other than a campaign by Shoshenq I of the 22 nd Dynasty, c. 925 BCE, which appears to have been a singular event, there is little evidence for Egyptian presence or activity in the southern Levant. In addition, with some exceptions, the number of Egyptian and Egyptian-style objects found at sites in the southern Levant is also small, perhaps as a result of the rise of the Assyrian Empire as the dominant power over the southern Levant. During the Third Intermediate Period, Palestine fell increasingly into the Assyrian, then Babylonian, political sphere of influence, and the number of Egyptian-style objects found in the southern Levant continued to decline.

“Egyptian activity in the southern Levant remained minimal into the Late Period (712–332 B.C.), contemporary with Palestinian Iron Age IIC and the Persian Period. Whi le Egyptian artifacts are found at Palestinian sites during this era, they represent just one type of foreign import among many, rather than a dominant cultural or political orientation. Egyptian presence and activity in the southern Lev ant was mitigated by Persian control, and in this period the phenomenon of independent Egyptian activity in Palestine came to an end.”

Egyptian Rule over Canaan

Roger Atwood wrote in Archaeology magazine: “For three centuries, Egyptians ruled the land of Canaan. They built fortresses, mansions, and agricultural estates from Gaza to Galilee, taking Canaan’s finest products — copper from Dead Sea mines, cedar from Lebanon, olive oil and wine from the Mediterranean coast, along with untold numbers of slaves and concubines — and sending them overland and across the Mediterranean and Red Seas to Egypt to please its elites. A basalt stele excavated at Beth Shean depicts the victory of the pharaoh Seti I, who reasserted Egyptian rule over Canaan in the 13th century B.C. [Source: Roger Atwood, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2017]

Separated by the Sinai, a bleak and sparsely populated land in antiquity as now, Egypt and Canaan were neighbors whose histories of war, trade, and migration intersected and intertwined over millennia. Egypt’s powerful centralized government ruled along the Nile, where pharaohs built the pyramids of Giza and reigned like gods over people who worshipped them. In contrast, Canaan was a land of warring city-states and hill tribes, spread out over what are now Israel, Lebanon, southwestern Syria, and the West Bank. At Canaan’s peak, there were about 20 such city-states in the southern area alone. Their culture was rustic, their power decentralized and weak.

Wealthy Canaanites adopted many Egyptian customs and decorative motifs, such as clay coffins dating to the 13th century B.C. from Deir el-Balah in Gaza and the Eye of Horus such as this faience one found at Jaffa in Israel.As with many colonial ventures before and since, military conquest led to a new cultural order in the occupied lands. Across Israel, archaeologists have found evidence that Canaanites took to Egyptian customs. They created items worthy of tombs on the Nile, including clay coffins modeled with human faces and burial goods such as faience necklaces and decorated pots. They also adopted Egyptian imagery such as sphinxes and scarabs. For the Egyptians, Canaan was a major trophy. Artists in Egypt carved and painted narratives on the stone walls of temples boasting about vanquished subjects and depicting Canaanite prisoners naked and bound at the wrists.

Why the Egyptians Want Canaan

Roger Atwood wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Canaan had great mineral and agricultural wealth — and the Egyptians coveted it. As early as the third millennium B.C., the Egyptians established busy trading posts in the coastal city of Ashkelon and in Gezer in the center of the region to buy up exotic products and transport them to Egypt on donkeys, which had only recently been domesticated. A few centuries later, the Egyptians began trading by ship with the seaport of Byblos on the coast of modern Lebanon, bypassing southern Canaan, whose ties with Egypt languished. [Source: Roger Atwood, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2017]

Over time, Canaan’s states strengthened and, around 1700 B.C., they invaded northern Egypt with a devastating innovation — the horse-drawn chariot — followed by settlers who built cities in the marshy Nile Delta. Known as the Hyksos, a Greek version of an Egyptian phrase that meant “foreign rulers,” they maintained their cultural habits and clashed with Egyptian rule to the south. Ultimately, the Egyptian state, reunified under the pharaoh Ahmose (r. 1550 — 1525 B.C.), expelled the Hyksos and sent them back to their homeland around 1540 B.C. A century later, newly self-confident and thirsty for expansion, the Egyptians found the right agent for their ambitions in Thutmose III ”

Thutmose III and the Invasion of Canaan

In his 19-year rule Thutmose III (r. 1479-1425 B.C.).” led military campaigns at a rate of almost one a year. There are lengthy descriptions of his battles on the rock walls of Karnak in the old Egyptian dynastic capital of Luxor. They include tales of soldiers hiding in baskets delivered to enemy cities and boats hauled 250 miles overland for a surprise attack. In the reliefs Thutmose himself is depicted as a sphinx trampling Nubians and a warrior smiting an Asiatic lion.

One of Thutmose’s greatest military victory occurred in Joppa (present-day Jaffa, Israel) in 1450 B.C. According to a rare papyrus text, the Egyptians secured victory after employing Trojan-horse-like deception. After the city failed to fall during a siege, the commanding general Djehuty sent baskets to the city that were said to contain plundered goods. At night Egyptian soldiers emerged from the baskets and opened the city gates.

Atwood wrote: Thutmose’s III “lithe, commanding figure can still be seen today smiting Canaanite masses in temple carvings at Karnak. “Egypt now saw itself as the center of the universe, and all its neighbors were considered enemies and targets for invasion,” says Daphna Ben-Tor, former curator of Egyptian archaeology at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. Egypt was at the threshold of the New Kingdom (1550 — 1070 B.C.), the artistic golden age of Hatshepsut, Akhenaten, and Tutankhamun. “As it became richer and reunified,” Ben-Tor says, “its appetite grew for the kinds of high-status goods that Canaan offered, such as copper, turquoise, and high-quality wood.” [Source: Roger Atwood, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2017]

“There were other objectives as well. Ruling Canaan allowed Egypt to check the expansion of the Hittite Empire and gave it control over trade routes from central Asia to the Mediterranean. “Egypt’s reason for being in Canaan was, first, strategic,” says archaeologist Israel Finkelstein of Tel Aviv University. “Canaan was important as a bridge to the north and the international routes to ports on the Mediterranean. Egypt could also exploit Canaan’s agricultural output,” he says. “The Egyptians imposed their rule and brought a certain stability while they exploited the land. Look at other empires through history — British, Roman — and you have that same balance of stability with exploitation.” Canaan’s rulers became vassals of the Egyptian state.

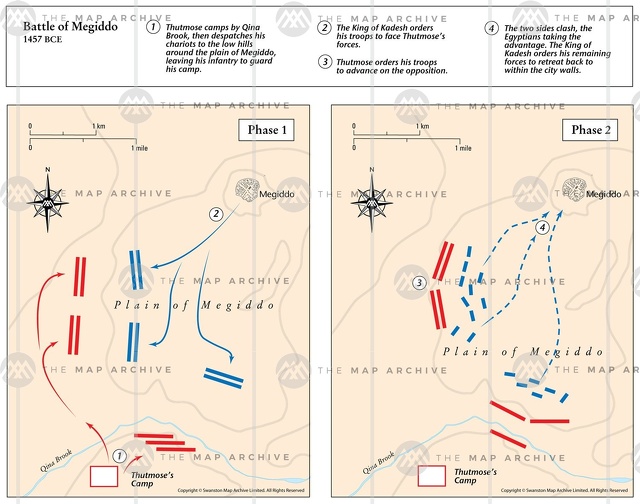

Battle of Megiddo

In 1458 B.C , armies of chariots and 10,000 foot soldiers under Thutmose III thundered through Gaza and defeated a coalition of Canaanite chiefdoms at Megiddo, in what is now northern Israel. This campaign, which is recorded in great detail on the walls of the temple he built in Karnak, revealed Tuthmosis III as a military genius.

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: In the second year of his reign, Thutmose found himself faced with a coalition of the princes from Kadesh and Megiddo, who had mobilized a large army. What’s more, the Mesopotamians and their kinsmen living in Syria refused to pay tribute and declared themselves free of Egypt. Undaunted, Thutmose immediately set out with his army. He crossed the Sinai desert and marched to the city of Gaza which had remained loyal to Egypt. The events of the campaign are well documented because Thutmose’s private secretary, Tjaneni, kept a record which was later copied and engraved onto the walls of the temple of Karnak. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Tuthmosis III used the element of surprise attack when he invaded Mediggo, using the least expecting route. This route was narrow, hilly, and difficult to pass, and it took over twelve hours to reach the valley on the other side. Tuthmosis III lead his men through the hills and when he made it to the valley he waited until the last man made it through safely. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Thutmose understood the value of logistics and lines of supply, the necessity of rapid movement, and the sudden surprise attack. He led by example and was probably the first person in history to take full advantage of sea power to support his campaigns. Megiddo was Thutmose’s first objective because it was a key point strategically. It had to be taken at all costs. When he reached Aruna, Thutmose held a council with all his generals. There were three routes to Megiddo: two long, easy, and level roads around the hills, which the enemy expected Thutmose to take, and a narrow, difficult route that cut through the hills. ^^

See Tuthmosis III and the Battle of Mediggo Under THUTMOSE III (1480-1426 B.C.): ANCIENT EGYPT’S GREATEST RULER? africame.factsanddetails.com

In the Old Testament, the Battle of Megiddo is called the Battle of Taanach. It was recorded in two accounts in Judges: one in prose (ch. 4), the other in poetry (ch. 5). Of the two, the poetic form is clearly the older of the two. See Battle of Taanach in HISTORY OF THE CANAANITES: ORIGINS, INVASIONS, BATTLES africame.factsanddetails.com

Egyptian Rule Over Canaan and the Worship of Hathor

Atwood wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Once in charge, the Egyptians set up a colonial administration in Canaan whose inner workings are well documented. The main source of information is the Amarna Letters, an archive of 382 clay tablets unearthed in the ancient Egyptian city of Amar-na over several years around 1900. Written in Akkadian cuneiform, the diplomatic lingua franca of the day, the letters give a rich sense of how abjectly the Canaanite chieftains obeyed the Egyptian ruler and how they jockeyed for his favor. [Source: Roger Atwood, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2017]

About 300 of the tablets were addressed directly to the pharaoh. One, written by the ruler of the city of Shechem to Amenhotep III, starts with the Canaanite vassal declaring himself “your servant and the dirt on which you tread. I fall at the feet of the king, my lord and my sun.” He then offers to send his own wife to the pharaoh if asked. In another letter, the ruler of Jerusalem frantically defends himself against accusations of disloyalty lodged by the leader of a rival city-state. In yet another, the king of Babylon demands justice for the murder of a Babylonian messenger who was crossing Canaan on his way to Egypt. “Canaan is your country, and its kings are your servants,” wrote the Babylonian. He enclosed a sapphire with the letter, to smooth tensions. Other letters relate more mundane business, such as details of food shipments or deliveries of horses.

“Sometimes the Canaanites added their own twists to Egyptian customs. About 130 clay coffins, some decorated with naturalistic human faces, have been excavated near Beth Shean and Gaza, another center of Egyptian control. Such caskets were commonly used in Egypt, but in Canaan they were filled not just with Egyptian-style mortuary goods, but also Canaanite items. Sometimes two people were buried in a single coffin, which was unheard of in Egypt but a common practice in Canaan.

Along with adopting Egyptian burial practices, or their version of them, the Canaanites also came to worship the Egyptian goddess Hathor. She was associated with love, music, and a kind of feminine grace that Egyptians and Canaanites alike admired, and was the only Egyptian deity absorbed into the Canaanite pantheon. Her distinctive look, with almond-shaped eyes, long curls, and the ears of a cow, appears on objects both plain and fine and in archaeological contexts ranging from houses to palaces.

Egyptian Statues, Sphinxes and Art in Canaan

Roger Atwood wrote in Archaeology magazine: The Egyptian colonists imported or re-created all the visual propaganda of their power, with objects expressing the permanence of their empire. At the site of Beth Shean, near the Sea of Galilee, a life-size basalt figure of a seated Ramesses III presided over the entrance to one of the main temples. Excavated in the early twentieth century by University of Pennsylvania Museum archaeologists and now in the Israel Museum, the statue was carved from locally quarried stone by imported Egyptian artisans. Beth Shean was occupied mostly by Egyptian soldiers, scribes, and colonial bureaucrats, but, at other sites, ordinary Canaanites would have seen similar political statements. [Source: Roger Atwood, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2017]

At Hazor, one of ancient Canaan’s largest cities, a team from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem recently found part of a sphinx made of gneiss, a valuable stone used by the Egyptians for statues of gods and rulers. The sphinx bears an inscription to Menkaure (r. 2490 — 2472 B.C.), a pharaoh who was originally interred in one of Giza’s pyramids. Yet the layer of the excavation in Hazor where the statue was found dates from centuries later in the mid-second millennium B.C. The sphinx had probably been imported from Egypt to lend status to a temple, a relic from the old days meant to lend prestige to Egypt’s new colony.

“Egypt’s power wasn’t felt only in mighty sculptures. It also wielded a strong cultural pull on Canaan’s elite, who were attracted to Egypt’s graceful jewelry and symbols. Archaeologists have found hundreds of Egyptian-style objects in Canaanite burials, including alabaster, glass, and carnelian jewelry, scarabs decorated with sphinxes and hieroglyphs, and clay pots. Wealthy Canaanites liked to stock their tombs with imitations of Egyptian ushabti, figurines of people who would tend to the dead in the afterlife. “There was an Egyptianization, so to speak, of Canaan’s material culture,” says Ben-Tor. “The Canaanites were burying their dead with objects imported from Egypt

Jaffa — a Port Grudgingly Under Egyptian Control

Perhaps the greatest Egyptian city in Palestine was the port of Jaffa. Atwood wrote: “Built on a hilltop overlooking the sea, Jaffa’s history of settlement stretches back more than 5,000 years. Its modern seaport, filled with fishing dinghies and yachts, faces the Mediterranean on the hill’s western side. But in antiquity the port was on the opposite side, east of the city, up a marshy estuary that protected ships from storms and impeded access to the city over land. Egypt captured Jaffa during Thutmose III’s first wave of conquest, a victory described in a tale called the “Taking of Joppa” (Joppa being an old name for Jaffa) that appears on a papyrus discovered in Egypt around 1870, now in the British Museum. The story goes that the Egyptian commander Djehuti feigned surrender after being rebuffed in his attempt to take Jaffa. He then offered 200 baskets as tribute to the Canaanites. Concealed in the baskets were Egyptian soldiers who, once inside the city, leapt out and conquered it. [Source: Roger Atwood, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2017]

“In Egyptian times, anyone entering Jaffa passed under an imposing square gate made of two mudbrick towers joined on top by a wide, two-story wooden bridge that formed a covered passageway. American archaeologist Jacob Kaplan excavated fragments of the gate’s monumental facade around 1960. He found less than half its decorative elements, but enough remained to discern the gate’s carved invocation to Egypt’s — and now Canaan’s — absolute ruler: “Horus-Falcon, Strong Bull, Beloved of Maat, King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Usermaatre Setepenre, Son of Re, Lord of Crowns, Ramesses.” Archaeologist Aaron Burke of the University of California, Los Angeles, says, “This gate said to everyone who came, ‘This is Egypt.’”

“Burke and Martin Peilstöcker of Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz have revealed a city of soldiers and Egyptian transplants, living on grains and fruits brought by Canaanite farmers to the Ramesses gate. Kaplan had uncovered 22 brewing pots, identical to those that appear in Egyptian wall paintings, showing that the soldiers brewed their own beer. They also had mementos from home, including several scarabs depicting Amenhotep III. Other finds, such as large Cypriot storage jars and fragments of Mycenaean vessels, point to the city’s cosmopolitan trade ties. But hardly any local wares have been found. “Given the lack of Canaanite objects inside the city walls, and the fires that destroyed it, it’s safe to say the Egyptians didn’t get along with the people living nearby,” says Peilstöcker. “If you just followed the biblical texts, you would think this was a very peaceful period, that the Egyptians were kind overlords. We find violence and upheaval.”

“Canaanites elsewhere may have warmed to Egyptian rule, but not in Jaffa. It was a foreign outpost in an often hostile land, says Burke. The absence of Canaanite materials from the Egyptian period inside the city’s walls attests to the strained relationship between the two communities, he believes. “We can reconstruct the whole hierarchy of Egyptian control here: the way the city gained a military foothold, reached its height during the time of Ramesses II, and then was abandoned, and in almost all that time it was isolated from the surrounding Canaanite culture” — so isolated, in fact, that elite Egyptian men brought their wives, he says, suggesting colonial officers spurned local women. “The lower ranks may have married local girls.” The Egyptians wouldn’t even bury their dead in this foreign land. Burke has found no Egyptian graves in Jaffa because, he believes, Egyptian corpses were sent home for burial. The Egyptians imported their own ceramics and even delicacies such as Nile perch, a few bones of which have been found.

Decline Egyptian Canaan

Atwood wrote: “Egypt’s presence in Canaan ended sooner than the pharaohs might have expected. With Canaan under assault from seaborne invaders and hit by drought so severe it caused food shortages, Egypt’s colonial rule began to crumble around 1200 B.C., starting in the north and gradually spreading south. Egypt did not fall alone. The eastern Mediterranean’s two other great powers of the day, the Hittites in central Turkey and the Mycenaeans in Greece, saw their capitals sacked and their governments fail. They all toppled in the pan-Mediterranean Late Bronze Age collapse of the twelfth century B.C. Egypt’s 2,000-year-old dynastic system survived, but it lost its trade ties throughout the Mediterranean and its valuable outposts in Canaan. [Source: Roger Atwood, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2017]

After Ramesses III (r. 1183 — 1153 B.C.) died, a line of much weaker rulers came to power — all named Ramesses and all incapable of dealing with the increasingly restive Canaanite masses. Severe drought took hold around 1200 B.C., confirmed recently by dates obtained from sediment levels in the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea. Hungry people migrated in search of reliable food sources, undermining the established order throughout the region. [Source: Roger Atwood, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2017]

Coastal cities came under assault from marauders contemporary scholars call the Sea Peoples. Their exact identity remains a mystery, but they likely included people from southwestern Turkey and the Aegean islands and were opportunistic raiders who burned and pillaged seaports and inland cities. “Canaan was in a spiraling collapse that, once it started, fed off itself,” says Eric Cline of George Washington University. “The invasion of the Sea Peoples was one factor, but there was drought and with it came famine.” Even before Ramesses III’s rule, loyal Canaanite lords had warned in their letters to the pharaoh of uprisings and plots by rival states, and archaeological evidence suggests insurrection swept the Canaanite interior. By 1130 B.C., people had burned down the Egyptian ruling compounds in Megiddo, Lachish, and at least a dozen other cities. At some, up to 15 feet of ash have been discovered. Finally, the spreading revolt reached Jaffa.

“Burke and Peilstöcker are finding that the fall of Egypt’s rule came the way Hemingway famously described bankruptcy — gradually, and then suddenly — and was at least partly due to homegrown factors. The Egyptian outpost at Jaffa had an uneasy relationship with the locals, and it apparently met a fiery end. Burke and Peilstöcker have found evidence of two catastrophic blazes, ten years apart, that destroyed Jaffa, the second one occurring in about 1125 B.C. That fire, Burke believes, marked the end of Egypt’s presence not just in Jaffa, but in all of Canaan. “Jaffa was the only Egyptian outpost that was purely military. This was their last line of defense, and once it fell, any remaining Egyptian centers in Canaan would have been cut off from Egypt,” says Burke. He has been excavating the site since 2007, following on digs starting in the 1950s that revealed Jaffa as a walled enclave of pharaonic power whose strained relationship with the surrounding people stood in sharp contrast to the cultural affinity between Egyptians and Canaanites elsewhere. Burke says, “They lived largely at odds with each other. And after the Egyptians left, there is no further trace of their presence here.”

Was the Jaffa Revolt the End of the Egyptians in Canaan

Atwood wrote: “The beginning of Egyptian rule in Canaan, with that smashing victory at Megiddo, is much clearer than its end. Archaeologists digging the remains of Egyptian sites in Israel and combing through ancient texts carved into temple walls and scratched onto clay tablets have never been able to pinpoint exactly when, or even how, Egypt’s occupation of Canaan expired. Did it decline slowly or end suddenly? Was it an orderly withdrawal or a messy rout? Did it fall in the region-wide cataclysm of the Late Bronze Age or were local factors more to blame?

“The revolt that Burke believes ended Egypt’s rule in Jaffa started about 1135 B.C., when the Ramesses gate burned down. It was rebuilt, but burned again some 10 years later. Burke believes the intensity of the heat from both fires shows that they were deliberately set. [Source: Roger Atwood, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2017]

Archaeologists have unearthed numerous weapons, including these arrowheads, which have allowed them to reconstruct Jaffa’s final, tumultuous moments.In the second blaze, mudbricks facing the covered passageway were singed with such heat that they turned a reddish brown, as if fired in a kiln. Ceramics burned to ash. Fragments of antlers belonging to 32 deer that decorated the passageway were partly melted. Passengers aboard ships in the Mediterranean would have seen billows of black smoke as Jaffa’s wood-and-thatch roofs blazed. According to Burke, the circumstantial evidence suggests that Canaanites set the fire themselves. He says, “Could it have been Sea Peoples? Maybe. But the dates we found are 50 years after destructions associated with them.”

“Burke and Peilstöcker have been able to reconstruct roughly how Jaffa’s final insurrection transpired. The team has recovered bent arrowheads, a spearhead, and a lead weight inside the Ramesses gate, where the fighting must have broken out. They think that the attackers then set fire to the wooden platform between the two towers. It collapsed into the passageway below, on top of piles of seeds, olives, pistachios, lentils, dates, grapes, and wheat. Radiocarbon dating of 21 scorched seeds shows that the fire happened between 1134 and 1115 B.C., with the highest probability falling at 1125 B.C. Burke says that this is the latest confirmed date of Egyptian settlement in Canaan. Yet some scholars are skeptical it all ended in Jaffa.

The ruins of a 500-year-old Ottoman fortress stand on the site of Aphek, a few miles east of Jaffa. Aphek likely supplied much of the grain that fed Jaffa’s Egyptian soldiers. The city also burned in the civil unrest that destroyed the garrison there.Into the beginning of the next century, there would be an Egyptian presence in Beth Shean, says Ben-Tor. “Jaffa wasn’t the last Egyptian center,” she says, “although it fell around the same time as the others.” In any case, nearby Egyptian outposts also experienced fiery ends. Twelve miles inland from Jaffa stood the granary estate of Aphek, where today stand the ruins of a sixteenth-century Ottoman fortress. Excavations in the 1970s by archaeologists from Tel Aviv University found the granary buried under six feet of charred timbers and debris. Aphek’s destruction suggests that the torching of Jaffa was not an isolated attack, but rather a component part of a general insurrection. Burke surmises it probably disrupted Jaffa’s grain supplies, making the Egyptians’ position that much more precarious. In 1125 B.C., the sight, from Jaffa, of smoke rising from Aphek would have made clear that Egypt’s rule in Canaan was over.

Egyptians in Iron Age Palestine

Abercrombie wrote: “Although it may be interpreted from Egyptian written sources that Egypt exercised little control over this region after the Nineteenth Dynasty (1292 -1189 B.C.), the archaeological evidence from Palestine suggests otherwise at least for the first kings of the Twentieth Dynasty (1189 to 1077 B.C.). Beth Shan remained an Egyptian colony with houses built according to Egyptian style, complete with door lintel inscriptions in hieroglyphics. [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|]

“Egyptian architectural structures, square-shaped houses made of mud-brick, occur at Aphek, Ashdod, Beth Shan (1550 and 1700 houses), Gaza, Hesi, Jemmeh, Joppa, Tell el-Farah S (Sharuhen) and Tell Masos and Tell esh- Sharia (Ziklag). The Timna copper mines continue to be controlled until perhaps Ramesis VI. Egyptian pottery can be cited from many early the early Iron Age sites as well. In summary, it seems at least plausible to suggest that Egypt continued to dominate this region at least until the mid-part of the century and perhaps to the end of the century at least at Beth Shan. |*|

“Egyptian contact in the late Iron Age is limited to minor incursions. I Kings 9:16 records that the Egyptian Pharaoh destroyed Gezer. Shishak, the first Pharaoh of the 22nd Dynasty, led a military campaign during the fifth year of Rehoboam, Solomon's son (1 Kings 14:25-26, 2 Chronicles 12:2- 9). A boundary stela of the Egyptian monarch was set up at Megiddo, and the king recorded his victory on the first pylon at the Temple of Karnak. At the end of the seventh century, Egyptian forces attempted to defeat the army of Sennacherib. Necco, Pharaoh of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, campaigned in Palestine and northward to the Euphrates in 609. Necco's forces defeated Josiah at the Battle of Megiddo where the Judah king was slain in battle (2 Kings 23:29-30, 2 Chronicles 35:20-25).” |*|

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com, Archaeology magazine

Last updated July 2024