Home | Category: Themes, Early History, Archaeology

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

"boomerangs" in King Tut's tomb, actually magic wands Egypt can be an extremely challenging places to do archaeological digs. In Luxor, for example, temperatures often rise above 38°C (100°F).

Dr Joyce Tyldesley wrote:Our fascination with ancient Egypt is, to a large extent, a product of the vast amount of material information available. We know so much about the daily lives of the ancient Egyptians-we can read their words, meet their families, feel their clothes, taste their food and drink, enter their tombs and even touch their bodies-that it seems that we almost know them. And knowing them, maybe even loving them, we feel that we can understand the very human hopes and fears that dominated their lives. [Source: Dr Joyce Tyldesley, BBC, Liverpool University, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Scholars often use hairstyles to date mummies and images and objects with human figures on them. Artifacts dated using tree rings include timbers from an Egyptian shipwrecks that revealed a gold scarab with Queen Nefertari's name, cut in 1316 B.C. Unraveling the genealogies and pharaohs and their queens is difficult. The historical records are incomplete, tombs have been disturbed (with the mummies of rulers put back in the wrong caskets) and brothers and sisters and even fathers and daughters intermarried.

By one estimate one day in the field generates three or four days work in the laboratory as reliefs are compared to others; pottery is reconstructed and dated; bones are identified and tested; and research is carried out in libraries, computers and offices. Archaeologists have to deal finding stuff under cities and private agricultural land needed by farmers. Those working in tombs often cough up flecks of mud. This is called "tomb cough.”

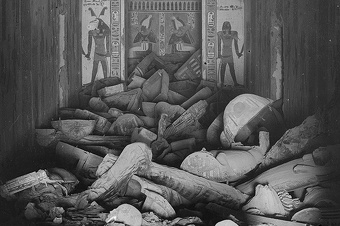

Only since the early 1970s has proper archaeology techniques been widely applied in Egypt. Before then pyramids were blasted open with explosives; doors to tombs were knocked opened with battering rams; and coffins were hastily pried to open to get at the potential goodies that lay inside them. Expose to air and humidity after sealed tombs are opened are among the biggest dangers to artwork (See King Tut's Tomb). Modern alternations of the topography around the Valley of Kings has created channels that directs waters from rainstorms directly into the tombs. One particularly nasty storm in November 1994 generated flash floods, with waters that reached speeds of 30mph, severely damaged several tombs. Fortunately major flash floods occur only once very 300 years or so.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt” by Kathryn A. Bard Amazon.com;

“Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt” by Steven Blake Shubert and Kathryn A. Bard (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Egyptology” by Ian Shaw and Elizabeth Bloxam (2020)

Amazon.com;

“Treasures of Egypt: A Legacy in Photographs from the Pyramids to Cleopatra” by National Geographic (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Early Egypt: Social Transformations in North-East Africa, c.10,000 to 2,650 BC” (Cambridge World Archaeology) by David Wengrow (2006) Amazon.com;

”Travels in Egypt and Nubia: (Expanded, Annotated)” by Giovanni Battista Belzoni (1778-1823) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Ancient Egypt: Beyond Pharaohs”

by Douglas J. Brewer (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Many Histories of Naqada: Archaeology and Heritage in an Upper Egyptian Region” (GHP Egyptology) by Alice Stevenson and Joris Van Wetering (2020) Amazon.com;

“A Manual of Egyptian Pottery, Volume 2: Naqada III - Middle Kingdom” (Aera Field Manual Series) by Anna Wodzinska (2011) Amazon.com;

“Experiments in Egyptian Archaeology: Stoneworking Technology in Ancient Egypt”

by Denys A. Stocks Amazon.com;

“Egyptology: Search for the Tomb of Osiris” by Dugald Steer (2004) Novel Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Ancient Egyptian Excavations and Archaeological Work

Around 70 percent of Egypt’s ancient ruins remain buried in the sands. Important work is being today at Tell el-Amarna, the site of the late 18th Dynasty royal city of Akhetaten; Tell Edfu, which preserves about 3,000 years’ worth of history in a single mound ; the Valley of the Kings and the nearby worker’s village of Deir el-Medina; and the areas in and around the Pyramids of Giza and Saqqara,

Most of the work has traditionally been done by Egyptian workers who sometimes hand baskets to each other along human chains and sing while they work. They typically worked from 6:30am to 1:30pm, when it gets too hot. Describing the excavators near the pyramids at work, Virginia Morrel wrote in National Geographic: “A workman named Said Saleh is digging. He fills each bucket with sandy soil. And one by one the workers hoist up their buckets, then walk down the slope to dump the sand on a pile, which two archaeologists run through a sieve. There’s a steady rhythm of digging, hoisting, and dumping.”

Describing a 125 person crew at work in Abydos, Kenneth Garret wrote in National Geographic” “‘Yellah! Yellah! Yellah!’ barks...the Egyptian crew boss, spurring his workers to move it, move it...The mostly teenage boys hauling buckets of sand giggle nervously but pick up the pace while keeping an eye on their ranting foreman...with a cast from a long, intimidating stick-wand he keeps clutched behind his back...As a line of workers use hoe-like tureyas to scrape away the sand, the so-named bucket boys haul away clanking pails of dirt and pour it like water onto of the laps of sifters... Excavators are on the ground with trowels in hand, surveyors are plotting the coordinates of artefacts, a photographer is documenting each new find, and illustrators are pencil drawing an ancient coffin of an infant skeleton. Kneeling on one knee in the center of this swarm” is an archaeologist “brushing sand away to reveal a smooth, ancient mud floor.”

Amarna — A Great Place to Do Archaeology

bathroom at a house in Amarna

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “Tell el-Amarna is the site of the late 18th Dynasty royal city of Akhetaten, the most extensively studied settlement from ancient Egypt. It is located on the Nile River around 300 kilometers south of Cairo, almost exactly halfway between the ancient cities of Memphis and Thebes, within what was the 15th Upper Egyptian nome. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Founded by the “monotheistic” king Akhenaten in around 1347 BCE as the cult center for the solar god, the Aten, the city was home to the royal court and a population of some 20,000-50,000 people. It was a virgin foundation, built on land that had neither been occupied by a substantial settlement nor dedicated to another god before. And it was famously short-lived, being largely abandoned shortly after Akhenaten’s death, some 12 years after its foundation, during the reign of Tutankhaten; a small settlement probably remained in the south of the city. Parts of the site were reoccupied during late antique times and are settled today, but archaeologists have nonetheless been able to obtain large exposures of the 18th Dynasty city. Excavation and survey has taken place at Amarna on and off for over a century, and annually since 19.

From a historical viewpoint, Akhetaten was never one of ancient Egypt’s great cities or religious centers, rivaling Thebes or Memphis. The importance ascribed to Amarna originates largely from modern scholarship, for two main reasons. The first is that it formed the arena on which one of the most unusual, and in some respects transformative, episodes in ancient Egyptian history played out. The second is its contribution to the study of urbanism in the ancient world.

“In addition to its historical significance, Amarna is our most complete example of an ancient Egyptian city. Allowing for its unusually short period of occupation, and the particulars of Akhenaten’s reign, it serves as a fundamental case site for the study of settl ement planning, the shape of society, and the manner in which ancient Egyptian cities functioned and were experienced. Overall, the city has a fairly organic layout, albeit with hints of planning: the line of the Royal Road seems to have formed an axis al ong which key buildings such as the North Palace, the temples and palaces of the Central City, and the Kom el-Nana complex were laid out, and it is probably not a coincidence that the axis of the Small Aten Temple lines up with the mouth of the Royal Wadi. Scholarly opinion differs, however, on the extent to which the city was formally designed, and particularly how far it was laid out according to a symbolic blueprint befitting its status as cult home for the Aten. Less contentious is the observation that the residential areas of Akhetaten developed in a fairly piecemeal manner, the smaller houses built abutting one another, often fitting into cramped spaces, and with thoroughfares developin g in the areas between —although the city presumably never reached the kind of urban density of long-lived settlements such as Thebes and Memphis.”

See Separate Article: AMARNA: LAYOUT, BUILDINGS, AREAS, HOUSES, INFRASTRUCTURE africame.factsanddetails.com

Study of the Pyramids

Dr Ian Shaw of the University of Liverpool wrote for the BBC: “There is still a great deal that remains mysterious about the basic structure of pyramids, and the technology that created them. If we are to gain a better understanding of pyramid-building, the best way seems to be a blend of detailed study of the archaeological remains and various kinds of innovative experimental work. Above all, this is the kind of research that relies on collaboration between Egyptologists and specialists in other disciplines, such as engineering, geology and astronomy. As far as stone masonry is concerned, many volumes have been published describing the surviving remains of pharaonic temples and tombs, whether in the form of traveller's accounts, archaeological reports or architectural histories (Badawy 1954-68, Smith 1958, being the first attempts to provide comprehensive historical surveys). [Source: Dr Ian Shaw, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Between 1880 and 1882, Flinders Petrie, the first truly scientific archaeologist to work in Egypt, undertook some careful survey work on the Giza plateau. This was the site of the pyramid complexes of the rulers Khufu, Khafra and ë-all of whom lived in the Fourth Dynasty....Although there have been many meticulous studies of specific sites or buildings, only a few-notably Petrie's surveys of the pyramids at Giza and Meydum in 1883 and 1892-have focused on the technological aspects of the structures. On the other hand, it is remarkable that, despite Petrie's concern with the minutiae of many aspects of craftwork and tools, his general works include no study of the structural engineering of the Pharaonic period. |::| This gap in the literature began to be filled in the 1920s with Reginald Engelbach's studies of obelisks (Engelbach 1922, 1923), Ludwig Borchardt's many detailed studies of pyramid complexes and sun temples (eg Borchardt 1926, 1928), and the first edition of Alfred Lucas' Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries (Lucas 1926), which included a substantial section devoted to the scientific study of stone working. |::|

Giza Pyramid Complex

“However, the first real turning point arrived in 1930 with the publication of Ancient Egyptian Masonry, in which Engelbach collaborated with Somers Clarke to produce a detailed technological study of Egyptian construction methods from quarry to building site (Clarke and Engelbach 1930). The meticulous excavations of George Reisner at Giza and elsewhere soon afterwards bore fruit in the form of the publication of The Development of the Egyptian Tomb down to the Accession of Cheops (Reisner 1936), and Reisner's work at Giza was later supplemented by the architectural reconstruction of the Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara by Jean-Philippe Lauer, whose Observations sur les pyramides (Lauer 1960) was also informed by a sense of the fundamental practicalities of ancient stone masonry. |::|

See Separate Article: STUDY OF THE PYRAMIDS: SERIOUS SCHOLARSHIP AND PSEUDOSCIENCE africame.factsanddetails.com

Evolution of the Temple of Karnak

The Temple of Karnak (3 kilometers, 2 miles north of Luxor) ranks with the Pyramids as most amazing site in Egypt and by some estimates is the largest religious structure ever created. Over two millennia it was enlarged and enriched by consecutive pharaohs until it covered 247 acres of land on the Nile’s east bank. At its height it stretched over an area of one mile by a half a mile — about half the size Manhattan — and was like a city, containing its own administrative offices, palaces, treasuries bakeries, breweries, granaries and schools. "Karnak" is the Arabic word for fort. It used to be called Ipetesut — “most esteemed of places.”

Karnak was built to mark the birthplace of Amun, the greatest of all Egyptian gods. It was probably built on a pre-existing sacred mound. It was built with money that the pharaohs earned in taxes and booty brought back from military victories.

The temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak experienced over 1,500 years of construction, destruction, renovation, and expansion. Its origin is traced to the ascendancy of the Intef family. The first hard evidence of a temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak appears during the reign of Intef II (2112-2063 B.C.), third ruler of the Eleventh Dynasty of Egypt. It is thought he erected a small mud-brick temple, probably with a stone-columned portico, on the east bank for the god Amun-Ra. Evidence for this construction comes from a sandstone column found reused at Karnak that includes an inscription dedicated by that king. [Source:Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

See Separate Article: HISTORY OF KARNAK TEMPLE AND ITS DEVELOPMENT UNDER NEW KINGDOM PHARAOHS africame.factsanddetails.com

Remote Sensing of Ancient Egyptian Tombs and Chambers

extracting a tooth sample from a mummy for DNA testing

Seismic waves are shot through sand, tomb walls and monuments to find out what may be lurking behind or below them. Magnetometers can detect tombs. Miniature cameras have bee placed in robots that penetrate deep into the unexplored interiors into tombs and pyramids and other places it is to dangerous for humans to tread. Underground radar does not work well when water is present.

Tombs and underground chambers are explored with drilling systems specially designed to inspect the tomb without allowing pollutants and enter to enter. The idea is to create an air lock, insert instruments without allowing air in and the resealing the chamber when the instruments are withdrawn. Sometimes the air inside the chamber is as valuable to scientists as the artifacts as it may have been unmolested since the tomb was sealed thousands of year ago, and provide clues and insights into that time.

To investigate a sealed chamber: 1) Ground penetrating radar is used to map the chamber and figure out the best place to drill. 2) The area to be drilled—often a limestone block of the chamber—is leveled and sanded and treated with an epoxy resin and fitted with an airlock that allows a heavy to drill to drill through the block without letting air in once the chamber has been penetrated. The hole is drilled a centimeter or so at a time, using a vacuum cleaner to remove stone powder. When penetration is near the drilling is done more carefully. 3) When the drilling is complete a tube is inserted to take air samples and camera probes are lowered in to scope the inside of the chamber. 4) When the investigation is complete the air lock is replaced with a semi-permanent seal. Similar technology is used in submarine rescues and probing inside nuclear reactors.

Using Satellite Imagery to Explore Ancient Egypt

Sarah Parcak, an Egyptologist and professor of anthropology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, uses satellite imagery and other remote sensing tools to explore existing and potential archaeological sites in Egypt and elsewhere, As of 2016 she and her team had spotted more than 3,000 ancient settlements, more than a dozen pyramids and over a thousand lost tombs, and uncovered the city grid of Tanis, of Raiders of the Lost Ark fame. Abigail Tucker wrote in Smithsonian magazine: After the Arab Spring, in 2011, she created, via satellite, a first-of-its-kind countrywide looting map, documenting how plundered tombs first appeared as little black pimples on the landscape and then spread like a rash. She has pointed out the ruins of an amphitheater at the Roman harbor of Portus to archaeologists who had spent their whole careers digging above it, mapped the ancient Dacian capital of what is now Romania, and — using hyperspectral camera data — aided in the ongoing search for prehistoric hominid fossils in eroded Kenyan lake beds. [Source: Abigail Tucker, Smithsonian magazine, December 2016]

“In the lab, Parcak’s ancient computer calls up on the screen a hand-drawn Napoleonic map of the Nile, albeit in digitized form. “It’s kind of like French Google Earth from 200 years ago,” she says. She points out a “village ruiné” that has caught her eye: She hopes the image will lead her closer to the city of Itjtawy, the lost capital of Middle Kingdom Egypt. “It doesn’t matter how modern our images are,” she explains. “We always go back to every map that’s ever been made, because they contain information that no longer exists. ” Only after scrutinizing local architecture and landscape changes over millennia will she study data-rich satellite images that reveal latent terrestrial clues. She’s already used NASA radar to locate a wealthy suburb of Itjtawy, a find she has confirmed on the ground by analyzing soil samples that reveal bits of worked amethyst and other valued stones. Along with cross-referencing colonial-era surveys, the next step is to layer satellite images to make a 3-D topographical map of the area, which might indicate where the ancients chose to build on rises in the ground, to escape Nile flooding. “People think I’m Harry Potter, and I wave a wand over an image and something appears and it looks easy,” she says. “Any discovery in remote sensing rests on hundreds of hours of deep, deep study. Before looking at satellite imagery of a cemetery or a pyramid field, you have to already understand why something should be there. ”

“At Yale University, Parcak studied Egyptology and archaeology and embarked on her first of many Egyptian digs. But in her final year she spied a class on “remote sensing,” the study of the earth from afar. Parcak’s Yale professor warned that an archaeology student would flounder in his course, which was a tangle of algorithms, electromagnetic spectrum analyses and software programs. Parcak bombed the midterm. Toward the end of a semester of despair and stubborn cramming, though, came a moment of clarity: The whole field popped into view, like the base of an excavated pyramid. Parcak realized that her home turf of Egypt, because it’s an area of major Western government surveillance interest, offered some of the richest available satellite data on the planet. “All of a sudden,” she says, “I understood remote sensing. ”

“Today she toggles between cutting-edge satellite data and classic fieldwork. Often she’ll start with an open-access source like Google Earth to get a sense of the landscape, then zero in on a small area and, for a few hundred to several thousand dollars, purchase additional images from a private satellite company called DigitalGlobe. To show me a key procedure, she yanks out her iPhone and scrolls up...Plants growing over buried structures tend to be less healthy because their root systems are stunted. These differences in vigor are seldom apparent in visible light, the narrow part of the electromagnetic spectrum that the human eye can see: To humans, plants tend to look evenly green. But certain satellites record the infrared wavelengths reflected by the plant’s chlorophyll. Using false colors and software programs, Parcak tweaks these differences until the healthy plants look redder on screen, and sicker ones appear pink.

Looting of Ancient Egypt

Nearly all the tombs of pharaohs and ancient Egyptian noblemen and priest have been looted, many of them soon after they were built. Many are believed to be have been much grander than the tomb of King Tutankhamun and contained much more impressive funerary objects. The grand objects were found in Tutankhamun’s tombs even though it most of its rooms had been looted.

A fragment of 3,000-year-old papyrus in Turin, Italy recounts the trial of a thief who confessed after torture to breaking in to the tombs of Ramses the Great and his children. During the 20th and 21st dynasties, looting was quite common. In some cases the mummies of pharaohs were moved to new locations and looters left behind graffiti that helped archaeologists place when the deeds were done. See Ramesside Tomb Robberies Under CRIME IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com

In the age of the pharaohs, the tombs were guarded by priests and the punishment for looters was being impaled alive, condemned to the "flame of Skehment" or "f**ked" by donkeys. Still some looters took the risk. They pried open sarcophagi, unwrapped mummies and smashed everything in efforts to find hidden treasures. Mummies often had huge holes hacked in the chests and their face that were in all likelihood made by looters in search of treasures.

Early archaeologists in some cases were little more than grave robbers themselves. Murals were chopped off walls and mummies were unraveled in a search for treasure. One archaeologist burned 3,000-year-old coffins to heat his home. Another tore open 3,000-year-old necklaces at parties to demonstrate how fragile they were.

In the Valley of the Kings someone went into the tomb of Amenophis III (Amenhotep III)and cut out three head from a mural depicting the pharaoh’s life. Sharon Waxman, a former Washington Post and New York Times reporter, wrote in her book “Loot”: “It is shocking. Imagine the Mona Lisa’s face cut out on her canvas with kitchen knife.” The faces are now in the Louvre with the label “From the tomb of Amenophis III".

Intrusion of the Modern World on Ancient Egyptian Sites

The Sphinx, the pyramids and other Egyptian monuments are all being damaged to varying degrees by air pollution and the encroachment of Cairo urban sprawl. Things took a dramatic turn for the worse when archaeologists discovered that the Egyptian government was surreptitiously building an eight-lane super-highway, about a kilometer south of the Sphinx that violated international law.

The monuments of Giza are already hemmed into to the north and east by decrepit Cairo suburbs. The hope was to keep the south free of development so that the pyramids could be seen in the desert without the view being obstructed by a lot of buildings. The highway, scholars believe, will bring about a lot of unwanted development in the south that already includes highrise buildings, housing projects, two garbage dumps and a military factory "belching filthy black smoke." "The road," one archaeologist told the New York Times, "will encourage people to build shopping centers and gas stations, as well as other buildings. It will ruin the whole site."

Said Zulfica, an United nations official told the New York Times: "The Pyramids were meant to be mausoleums for the dead, but they will soon become part of an urban landscape if nothing is done to prevent this. The Pyramids will be surrounded like the Acropolis in Athens.”

Relocation of Abu Simbel

Abu Simbel (290 kilometers, 170 miles south of Aswan) is a monumental temple in southern Egypt with four colossal seated statues — two of Ramses the Great (Ramses II) and two of his wife Neferteri — and two main temples — one dedicated to the sun god Ra-Harakhte, Amun, Ra-Harmachis and Ptah, built into the cliff behind the colossal statues, and another dedicated to Hathor built into a cliff on an adjacent hill. Abu Simbel is 56 meters (185 feet) long and 27.5 meters (90 feet) high. The four colossal statues are cut from the living rock and are 18 meters (60 feet) high.

To escape the rising waters of a reservoir (5,250-square-kilometer Lake Nasser) created by the Aswan dam in the 1960s, the monuments of Abu Simbel were relocated from a cliff along the Nile to a site on a plateau 65 meters (212 feet) higher and 210 meters (690 feet) further inland. Between 1965 and 1968 the great temple of Abu Simbel was moved. Early proposals envisioned relocated the 67 foot statues by floating them on pontoons or inching them upwards with hydraulic jacks. But with money being a major concern a Swedish Company was hired; their plan was to cut Abu Simbel into segments and move them a piece at a time.

Abu Simbel consisted of two parts: a cliff-face statues and a temple built into the cliff. The temple also had to be removed piece by piece, but before that could be done several hundred feat of sold rock above it had to cleared away. This job alone more take more than a year, and engineers bit their nails nervously when ever dynamite had to be used. The cliff faces next to statues at the original site were also moved. The positioning of these blocks was not done as carefully as the placement of the stones, and construction workers derided their product as the Great Wall of China.

At the new site the temple was placed into a concrete dome, the size of an indoor arena, in back of the statues. When the temple and the statues were in place a bulldozer pushed up tons of rock, creating and an artificial hill in back of the statues and over the concrete dome. The new hills are 76 feet and 52 feet lower than the originals, but to build to their original height would have cost millions of dollars more. As it was the job coast US$36 million in 1965 dollars. [Source "Abu Simbel's Ancient Temples Reborn" by Georg Gerster, National Geographic May 1969]

“It was a huge undertaking,” Dr Mechtild Rössler, UNESCO’s director of Heritage Division and director of the World Heritage Centre, told the BBC. “One that I'm not sure could be done again today, with questions such as the ways a campaign of this magnitude would impact a region both environmentally and socially coming into play. ” [Source: Laura Kiniry, BBC, April 11, 2018]

How Abu Simbel Was Relocated

Laura Kiniry of BBC wrote: Beginning in November 1963, a group of hydrologists, engineers, archaeologists and other professionals set out on UNESCO’s multi-year plan to break down both temples, cutting them into precise blocks (807 for the Great Temple, 235 for the smaller one) that were then numbered, carefully moved and restored to their original grandeur within a specially created mountain facade. Workers even recalculated the exact measurements needed to recreate the same solar alignment, assuring that twice a year, on about 22 February (the date of Ramses II’s ascension to the throne) and 22 October (his birthday), the rising sun would continue to shine through a narrow opening to illuminate the sculpted face of King Ramses II and those of two other statues deep inside the Great Temple's interior. [Source: Laura Kiniry, BBC, April 11, 2018]

The Great Temple of Ramses II and a smaller one built for his wife Nefertari were cut into 1050 pieces, the heaviest weigh 33 tons. The pieces were cut with handsaws — not mechanical saws because the "vibrations from machines might have cracked the brittle limestone" — and freed from the cliff face with wedges. Iron chains were then wrapped around the segments of the statues, which were lifted by a derrick with a huge crane. The segments were swung around and lowered to the back of trucks cushioned with sand. The trucks inched forward gingerly and carried the segments to a storage area, where the segments stayed for a year to two until it was time for them to be fitted into place.[Source "Abu Simbel's Ancient Temples Reborn" by Georg Gerster, National Geographic May 1969]

Skilled workmen wielded the saws. These men had spent their working lives cutting and moving stone. "We know rocks like hearts," one of them said. "We know when they break." Before each section was cut surveyors implanted markers to gage the exact position of each segment in relationship to the rest of the structure. They margin of error engineers allowed was less than a fifth of a centimeter (12th of an inch).

There only real snag came after the Nefertari shrine had been reassembled. Because hydraulic engineers changed their mind and decided to raise the lake a meter (three feet) higher than originally planned the entire shrine had to be taken apart and rebuilt again 2.1 meters (seven feet) higher. There was also a murder on the site. An Egyptian workman killed one of his cohorts and planted the body near a pile of rubble near a blasting site. He was counting on the explosion to make it look it look like an accident killed him, but his plan was foiled when a Swedish engineer noticed an arm sticking out of the rocks. Before the murderer was caught 100 men from his village quit their job out of fear of reprisals. The biggest day to day fear was scorpions and horned vipers.

Finally, in September 1968, a colorful ceremony marked the completion of the job. The project was finished with three months to spare, when the job was complete the cofferdam which protected the site from rising water was breached and the former site of Abu Simbel was submerged under water.

Impact of the Relocation of Abu Simbel — UNESCO World Heritage Sites

The relocation of Abu Simbel was the first real meaty project undertaken by UNESCO and led to UNESCO creating a World Heritage list that helped save preserve Vienna's Historic Centre and Cambodia's Angkor Wat and many other sites. According to the BBC: UNESCO’s ‘Nubia Campaign’ came about in 1960, when the United Arab Republic (a political union of Egypt and Syria that existed between 1958 and 1961) began construction the Aswan Dam. While the dam would improve irrigation throughout the valley as well as significantly increase Egypt's hydroelectric output, it would completely submerge Abu Simbel's exquisite temples and many other temples and historic sites. [Source: Laura Kiniry, BBC, April 11, 2018]

In an effort to prevent the temples’ destruction, UNESCO embarked on its first-ever collaborative international rescue effort (the organization initially formed in 1945 to promote a joined culture of peace and prevent the outbreak of another war). This incredible effort later became the catalyst for a World Heritage list that would help protect and promote what now totals 1,073 significant cultural and natural sites around the globe.

“The completion of such an enormous and complex project helped [the organization] realise that we were capable of three main things,” Dr Rössler said. “First, bringing together the best expertise the world has to offer. Second, securing the international cooperation of its members [at the time totalling around 100 member states; today there are 195 member states and 10 associate members]. And third: assuring the responsibility of the international community to bring together funding and support that would help the world's heritage as a whole. ”

With momentum flowing, UNESCO continued launching campaigns, including the ongoing safeguarding of Venice, nearly destroyed by floods in the mid-1960s. In 1965, a White House conference in Washington DC proposed the formation of a ‘World Heritage Trust’ to continuously preserve the world's ‘superb natural and scenic areas and historic sites’. A few years later, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) crafted a similar proposal. But it wasn't until November 1972 that the General Conference of UNESCO adopted the Convention concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage, merging both drafts together to preserve cultural and natural heritage equally.

Restoration of the Tomb of Nefertari

The Tomb of Nefertari (in the Valley of the Queens near Luxor) is the most beautiful tomb in the Valley of the Queens or the Valley of the Kings and one of the most extraordinary works of art in the world. Over 3,200 year old, it is in amazingly good condition for its age and features extraordinary wall murals, painted with vivid colors, great skill and a wonderful sensitivity for detail.

On being inside the tomb, Marlise Simons wrote in the New York Times,"The effect is rich like a house hung with jewelry, and it has an intensity that appeals strongly to modern eyes. But what makes these galleries just as moving is the fine detail of the images, their exquisitely carved relief and the gestures of endearment that give the figures life...There is are sweetness and intimacy that makes contact across the centuries seem somehow possible."

Nefertari's Tomb was discovered in 1904 by Italian explorer Ernesto Shiaparellu, who was surprised by the tomb's excellent condition. The tomb was and neglected until 1986 when it was restored by an international team with a $3 million grant from the Getty Conservation Institute of California. Nefertari's Tomb was opened to the public in November 1995. Initially the price of admission was a $100. Then it was lowered to $60. As of the early 2000s it cost about $30 to get inside.

See Separate Article: TOMB OF NEFERTARI: CHAMBERS, PAINTINGS, MEANING OF THE ART africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art”by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024