Home | Category: Religion and Gods

HISTORY OF THE TEMPLE OF KARNAK

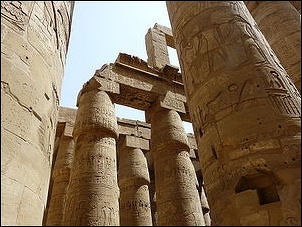

Hypostyle Hall columns

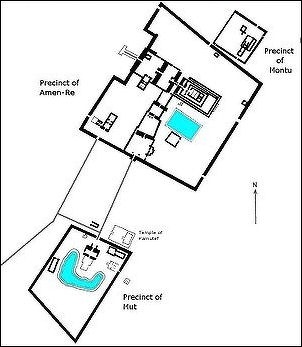

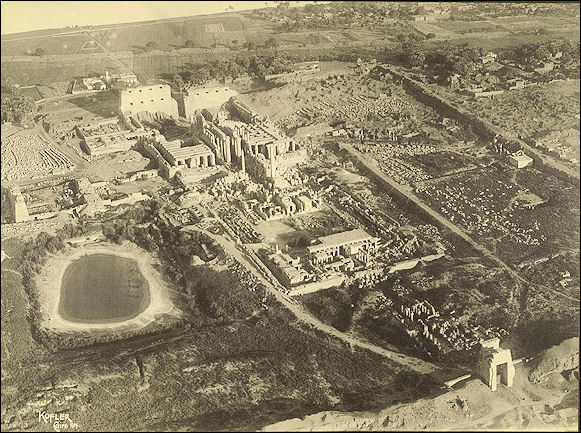

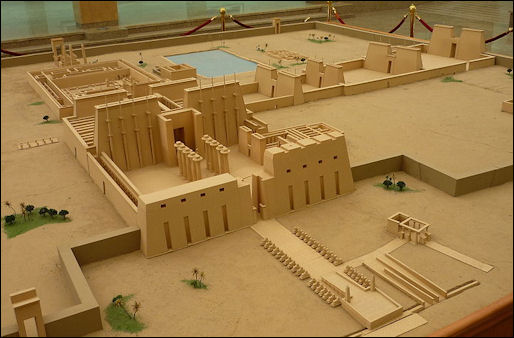

The Temple of Karnak (3 kilometers, 2 miles north of Luxor) ranks with the Pyramids as most amazing site in Egypt and by some estimates is the largest religious structure ever created. Over two millennia it was enlarged and enriched by consecutive pharaohs until it covered 247 acres of land on the Nile’s east bank. At its height it stretched over an area of one mile by a half a mile — about half the size Manhattan — and was like a city, containing its own administrative offices, palaces, treasuries bakeries, breweries, granaries and schools. "Karnak" is the Arabic word for fort. It used to be called Ipetesut — “most esteemed of places.”

Karnak was built to mark the birthplace of Amun, the greatest of all Egyptian gods. It was probably built on a pre-existing sacred mound. It was built with money that the pharaohs earned in taxes and booty brought back from military victories.

The temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak experienced over 1,500 years of construction, destruction, renovation, and expansion. Its origin is traced to the ascendancy of the Intef family. The first hard evidence of a temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak appears during the reign of Intef II (2112-2063 B.C.), third ruler of the Eleventh Dynasty of Egypt. It is thought he erected a small mud-brick temple, probably with a stone-columned portico, on the east bank for the god Amun-Ra. Evidence for this construction comes from a sandstone column found reused at Karnak that includes an inscription dedicated by that king. [Source:Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

One of the remaining wall inscriptions reads: "His Majesty exults at the beginning of battle, he delights to enter it; his heart is gratified at the sight of blood. He lops off the heads of his dissidents...His majesty slays them at one stroke — he leaves them no heir, and whoever escapes his hand is brought prisoner to Egypt." Another set of inscriptions describe the festival of Opet. The victories of Shoshenq I, a Libyan refereed to in the Bible as King Shishak, are immortalized on a relief at Karnak.

RELATED ARTICLES:

KARNAK TEMPLE: ITS HISTORY, COMPONENTS AND GREAT HYPOSTYLE HALL africame.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TEMPLES: HISTORY, TYPES, FEATURES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

COMPONENTS OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TEMPLES: SHRINES, DECORATIONS. MAMMASI africame.factsanddetails.com ;

STONE USED IN TEMPLES, MONUMENTS AND STATUES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

PRIESTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Karnak” by Elizabeth Blyth (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Temples of Karnak” by R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz (Author), Georges de Miré and Valentine de Miré (Photographers) Amazon.com;

“The Great Hypostyle Hall in the Temple of Amun at Karnak. Vol 1, Parts 2 and 3" by Peter J. Brand, Rosa Erika Feleg, William J. Murnane Amazon.com;

“The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Miracle: An Introduction to the Wisdom of the Temple” by R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz (1985) Amazon.com;

“Temple of the Cosmos: The Ancient Egyptian Experience of the Sacred” by Jeremy Naydler (1996) Amazon.com;

“Temples of Ancient Egypt” by Dieter Arnold (1997) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Temples” by Margaret Murray (1931) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Temples” by Steven R. Snape (1996) Amazon.com;

“Thebes in Egypt: A Guide to the Tombs and Temples of Ancient Luxor” by Nigel Strudwick (1999) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths,and Personal Practice” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

Chronology of the Settlements at Karnak

Marie Millet and Aurélia Masson wrote: “Continuous occupation from the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 B.C.) until the Late Roman Period is well attested at different locations in Karnak. It corresponds to the foundation of the first known Amun Temple, dated to the 11th Dynasty. However, recent research has found some ceramic material from the late Old Kingdom associated with mud-brick structures. It is unfortunately impossible to understand the nature of these structures as the evidence comes from a single deep sondage and is presently insufficient to provide a clear picture of the broader context of the finds.[Source: Marie Millet of the Louvre and Aurélia Masson of the British Museum, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“The orientation of the Middle Kingdom town is different from that of the Temple of Amun, which was established under the reign of Senusret I. Thus, the town probably predated this temple. It was planned as a square of 100 cubits and was most likely inhabited by people close to power and some craftsmen possibly working for the activities connected with the temple. Southeast of the sacred lake, the excavations uncovered an enclosure wall from the Middle Kingdom. South of this wall, small structures with thin walls belonged to a residential and craft area, whereas to the north, administrative buildings were most likely located. There are parallels for these mud-brick buildings with limestone column bases in Balat and Abydos.

“During the New Kingdom, the sanctuary of Amun was enlarged to a great extent. Settlements from the New Kingdom are seldom preserved within the sanctuary, and there are only few remains outside of it. The sanctuary probably did not allow houses to be built nearby. Of the architectural remains presently known, most were found on the south axis of the temple, and they show the same orientation as one of the Middle Kingdom towns. Ceramics and objects from the New Kingdom indicate the existence of settlements also on the eastern bank of the sacred lake. After the construction of the New Kingdom enclosure wall, the settlements within the sanctuary follow, most of the time, the new orientation given by this enclosure wall. Despite the important change during the 18th Dynasty, the town of the New Kingdom is still very poorly known. B. Kemp discussed the town’s enlargement, trying to compare its surface during the Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom. However, the recent study of the movements of the Nile linked to new archaeological investigations in Karnak tends to revise his hypothesis.

“The settlements of the first millennium B.C. that are the best known are connected with the religious activities in Karnak. The priests’ quarter mentioned above offers a good example of Third Intermediate Period and Late Period (712–332 B.C.) architecture. Each house varies in size (58 m2 for the smallest, 176 m2 for the biggest) and plan and has a well-defined boundary, even if they all stand next to each other. These contiguous houses share few typical features known from terraced houses. This functional and economical architecture can be found in many institutional programs of the Pharaonic Period.”

Construction and Funding of Karnak

Work was carried out on Karnak for 2,000 years beginning in the 12th dynasty (around 2000 B.C.) of the Middle Kingdom when an early temple was established and successive pharaohs added their own shrines and gates. Construction of buildings continued through the Middle and New Kingdom periods, with most of the work done between the XVIII Dynasty and the end of the Ramses era. In the XVIX Dynasty, 81,322 people, including priests and peasants, worked on the temple of Amon. Construction of the main hypostyle hall began in 1375 B.C. under Amenhotep III, and was continued under Seti I, his son Ramses II and was finally completed under Ramses IV.

Karnak was built from sandstone. Because it was easier to build a new temple from stones from an old temple than it was to quarry new stones, not much remains of the oldest temples because their stones were used to make newer structures. Over time the dimensions and buildings of each sanctuary changed according to the wishes of each successive pharaohs.

Supported by revenues from royal land endowments, Karnak became an economic power. Under Ramses III the “domain of Amun” covered 900 square miles of agricultural land, vineyards and marshlands, in addition to quarries and mines. Like many other monuments in Egypt, Karnak was covered by sand up until a century ago. When French soldiers first laid eyes on it in 1799, one lieutenant in Napoleon’s army wrote: “Without an order being given the men formed their ranks and presented arms, to the accompaniment of drums and the bands.” Exposure to the elements and the absorption of ground water has caused the columns to slowly deteriorate. The groundwater problem was caused by the Aswan Dam which has raised the level of the Nile and, along with it, the water table under Karnak.

The temple originally had a roof, and the columns were once plastered and painted with heroic scenes from the pharaohs lives. But mostly what remains now are some carved hieroglyphics and symbols, embellished by graffiti from 19th century British and Egyptian soldiers and 20th century tourists.

Origins of the Temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak

Elaine Sullivan of UCLA wrote: “The first incontrovertible evidence for the existence of a temple of Amun-Ra in the area of Karnak comes from the reign of Intef II in the First Intermediate Period (2181–2055 B.C.). However, Egyptologists initially suspected that a temple existed at the site as early as the Old Kingdom (This early temple would have been dedicated to the individual god Amun rather than the syncretized deity “Amun-Ra,” as existing texts refer to Amun-Ra only after the Old Kingdom.). The “chamber of ancestors” in the Akhmenu “Festival Hall” contained a series of reliefs depicting Thutmose III offering to a select group of kings whom he honored as his ancestors. Because the (destroyed) cartouche of the first king in the series was followed by that of Sneferu, the first king of the 4th Dynasty, and the names of four subsequent Old Kingdom kings, some scholars interpreted this modified king-list as a record of the rulers who contributed constructions to the temple, thus pushing the temple’s existence back substantially to the late 3rd or early 4th Dynasty (around 2700 to 2550 B.C.) . [Source: Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

A statue of the Old Kingdom king Niuserra Isi, found in Georges Legrain’s excavations at Karnak in the early 1900s, seemed to denote a tie between the Old Kingdom and a temple to Amun. However, the statue was not necessarily dedicated to the god Amun, and whether it originally stood within a temple to this deity is impossible to know. Indeed, Luc Gabolde of the Centre Franco- Égyptien d’Étude des Temples de Karnak (CFEETK) has recently identified a statue inscribed for Pepy I, “beloved of Amun-Ra, Lord of Thebes,” as a Late Period (712–332 B.C.) votive offering probably found at Karnak. If the practice of depositing statues of kings from former times was common, the presence of Old Kingdom statuary in the Karnak “cachette” would not verify the existence of an Old Kingdom temple. Gabolde, in his study of the Middle Kingdom court, noted that Old Kingdom ceramics were completely lacking in that area, as well as in other areas of the temple investigated down to the presumed level of the Old Kingdom. Unless new evidence is discovered, these findings suggest that a temple to Amun, or to Amun-Ra, did not exist at Karnak before the First Intermediate Period.

“With the ascendancy of the Intef family, the first hard evidence for the presence of a temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak appears. It was during this period of royal ambition and display that Intef II is thought to have erected a small mud-brick temple, probably with a stone-columned portico, on the east bank for the god Amun-Ra. Evidence for this construction comes from a sandstone column found reused at Karnak that includes an inscription dedicated by that king. A stela from the Intef cemetery on the west bank that mentions the “Temple of Amun” also provides support for the contention that such a cult place was operating prior to the Middle Kingdom. Gabolde’s CFEETK excavations since the late 1990s have refocused interest on the earliest periods of the Amun-Ra Temple at Karnak. A series of small sandstone-block platforms, no larger than 10 × 10 m, were examined. These platforms, located along the west side of the later “Middle Kingdom court,” lay below the levels of the thresholds of the Middle Kingdom temple of Senusret I (discussed below). Gabolde dated one phase of the reused sandstone in the series of platforms to the early Dynasty 11 kings based on a number of factors, including the similarity of the stone to other constructions of that period at Thebes. Other reused blocks, a few with fragments of relief scenes, could be dated to the later 11th and early 12th Dynasties. The platform therefore appeared to be the location of the original temple and portico of Intef II, dismantled soon after his reign, and replaced or rebuilt by the later 11th Dynasty kings and subsequently Amenemhat I at the same location.”

ariel view of Karnak

Karnak Temple Under Thutmose I and II in the Early New Kingdom

Elaine Sullivan of UCLA wrote: ““The construction efforts of Thutmose I had a great impact on the arrangement of the temple for years to come. Scholars have generally attributed both the fourth and fifth pylons to the king, as well as a corresponding stone enclosure wall, which together still form the core area of the temple. Thutmose I originally lined the court of the fifth pylon with a portico of 16 fasciculated columns. By erecting the first pair of granite obelisks at Karnak in front of the fourth pylon (the temple’s main gate at the time), Thutmose began an association of obelisks with the god Amun-Ra that may have bolstered the divinity’s rising universality. His act was emulated and outperformed (with taller and larger obelisks) by a number of 18th and 19th Dynasty rulers. [Source: Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Politically, Karnak took on new importance in the 18th Dynasty, as the pharaohs began to use the temple as a means of demonstrating their divinely ordained selection as king. The enhancements of Thutmose I highlight this change: among his contributions to the temple was the addition of a wadjet hall, where coronation rituals took place with the god Amun-Ra sanctioning the choice. The wadjet hall was originally an open-air court between the new fourth and fifth pylons of the king.

“Thutmose II added a new pylon to the west of the old temple entrance (later torn down for the construction of the third pylon, so it does not figure in the pylon numbering system at Karnak), creating a large “festival court,” enclosing the obelisks of Thutmose I within the building, and establishing a new western gate to Karnak. Along the hall’s south side, a small pylon entrance led to the constructions along the temple’s southern axis. Gabolde has used blocks found in the third pylon to reconstruct the appearance of the inscribed doors, side walls, and small pylon of the court.

“Thutmose II commissioned a pair of red granite obelisks, inscribed fragments of which have been found at Karnak, presumably for placement in his new hall. Gabolde has reconstructed (on paper) one of these monoliths. The preserved inscriptions of the king show that the monument originally belonged to him, but that he must have died before it could be completed and raised, as Hatshepsut added her own inscription, with a dedication to her father, Thutmose I. Two socles found subsumed by the third pylon and its gate likely mark the location of these obelisks .

“Tura limestone blocks probably recovered from the “cachette court” provide evidence that Thutmose II had constructed a two- roomed bark-shrine for the temple, similar in form to the later “Red Chapel” of Hatshepsut. The bark shrine may have stood in the future location of the Red Chapel, in front of the Senusret I temple, or it may have been positioned in the new “festival court” of the king. The chronology of its destruction is not defined, but modified inscriptions show it must have been dismantled between the ascension of Hatshepsut to the kingship and her proscription at the end of the reign of Thutmose III.

“A painted scene from the Theban tomb of Neferhotep (TT 49) implies that at some time in the 18th Dynasty, a giant T-shaped basin connected to the Nile by a canal was cut on the west side of the temple. A rectangular quay is depicted as flanking its eastern edge. If the basin was located in the vicinity of the later second pylon, as Michel Gitton suggested in his reconstruction of Karnak in the reign of Hatshepsut, the Nile must have shifted westward from its location in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.). It is perhaps this shift that allowed the westward expansion of the temple in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.). The presence of a canal and basin may equally have limited further movement of the temple west at this time.”

Karnak model

Karnak Temple Under Queen Hatshepsut

Elaine Sullivan of UCLA wrote: “The wadjet hall would be dramatically changed during the reign of Hatshepsut. The queen removed her father’s numerous stone columns and replaced them with five gilded- wood papyriform wadj-columns (wadj being the Egyptian term for papyrus). In the center of the hall she erected two red granite obelisks (one remains standing today) with electrum overlay. These tall monuments prevented her from roofing the hall completely, but she covered the side aisles of the hall with a wooden ceiling. The queen’s obelisks were dedicated to the celebration of her Sed Festival in the 16th year of her reign. [Source: Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Hatshepsut transformed the very core of Karnak, removing the Osiride portico of the Middle Kingdom temple and most of the forecourt constructions of Amenhotep I, including his entrance gate and bark chapels. To the front of Senusret’s temple, she appended a suite of rooms, her “Palace of Maat”. The queen ordered a beautiful two-roomed bark chapel of rose quartzite and black diorite, the Red Chapel, as a showpiece for Amun-Ra. In their recent republication of the chapel, CFEETK scholars concluded that the chapel’s placement was, as traditionally thought, within the Palace of Maat. As the insertion of the chapel into the Palace of Maat would only have been possible if renovations to the palace’s original rooms (including the removal of a number of the walls on the northern side) took place during the reign of the queen, it seems that Hatshepsut re-envisioned these rooms expressly to expand the area for her Red Chapel, finished only sometime around year 17 of her reign.

“Over 200 limestone blocks recovered primarily from the “cachette court” have been identified by Gabolde as part of a multiple- roomed structure (named the Netjery-Menu) dated to the early co-regency of the queen. Relief scenes and inscriptions depict Thutmose II, Hatshepsut, her daughter Neferura, and Thutmose III involved in the temple’s daily ritual. ....Another recently rediscovered monument of the queen’s was composed of a number of limestone niches dedicated to the royal statuary cult. These niches, also dated to the early years of the queen’s co-regency, were seemingly removed before she ascended to the throne as king. “Hatshepsut placed another pair of obelisks at the eastern edge of Karnak, outside the stone enclosure walls of Thutmose I. Although now destroyed, the obelisks are mentioned in a quarry inscription at Aswan and depicted in the queen’s temple at Deir el Bahri. Luc Gabolde and scholars from the CFEETK have been working on documenting pieces from these obelisks, and they have reconstructed their appearance as displaying a central line of hieroglyphs, flanked by scenes of Hatshepsut (and sometimes her nephew) with the god Amun-Ra. “A large stone pylon, the eighth, was constructed by the queen to the south of the temple, along what appears to have been the established north-south processional route...Reused blocks from the queen’s temple of Mut have recently been discovered during excavations at that site, and the Thutmoside temple and an accompanying triple bark-shrine at Luxor are known to have played a role in the queen’s Opet Festival ceremonies.”

Karnak

Karnak Temple Under Thutmose III

Elaine Sullivan of UCLA wrote: “Karnak experienced another period of vast change during the reign of Thutmose III. The greatest addition was a huge temple, the Akhmenu Festival Hall, placed behind Karnak’s east wall, built after the king’s 23rd year. The structure consisted of a large pillared hall leading to a set of three shrines, a series of rooms dedicated to the god Sokar, a hall decorated with relief scenes of flora and fauna observed during the king’s foreign military campaigns, a chamber with niched walls that served as the main shrine of the divine image, and an upper sun-court. The exact cultic nature of the temple remains elusive, but it may have held ceremonies for the regeneration of the king on earth. [Source: Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“A new stone enclosure wall was constructed, enclosing the Akhmenu in the greater temple complex. The obelisks of Hatshepsut were incorporated into a small contra-temple along the enclosure’s eastern wall. Contra-temples, usually appended to the rear wall of a temple and opening outward, provided a location for those not allowed within the temple proper (such as the public) to interact with the divinities. Often statues of the king were located at these shrines, and people would petition the images to act as intermediaries with the gods on their behalf. At the center of Karnak’s contra-temple stood a large calcite naos with a dyad of Thutmose III and the god Amun-Ra (although it originally may have depicted Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, with the queen’s figure later recarved).

“Thutmose III also added a stone pylon (the seventh) and connecting walls between the queen’s pylon and the temple wall along the southern processional route. In front of the pylon, he raised red granite obelisks. Along the east wall of the eighth pylon’s forecourt, he placed a calcite bark-shrine surrounded by peripteral pillars. This may have replaced the earlier calcite shrine of Amenhotep I at the same location, as Thutmose III gave his shrine an identical name.

“A huge sacred lake was cut into the space southeast of the temple. This may have been an expansion of a pre-existing lake at the same location. To the east of the lake a large mud- brick enclosure wall with exterior bastions was constructed, traditionally assigned to Thutmose III (although it may actually be older). The wall was enlarged and renovated in at least three phases, the last of which may date to as late as the 25th Dynasty...To the north of the main precinct, the king erected a small sandstone temple to the god Ptah (possibly replacing an earlier one of mud-brick). A hall with two columns fronted the temple’s triple sanctuary.

“Within the central core of Karnak, Thutmose III ordered significant remodeling. Behind the fifth pylon, he had a smaller pylon erected, the sixth, creating a small pillared court in front of the Palace of Maat. He replaced the limestone chapels of Amenhotep I along the sides of this court with sandstone replicas whose decoration commemorated the earlier king. Walls were appended to the east faces of the fifth and sixth pylons and a granite gate was erected between the pylons, creating a corridor along the temple’s central axis to the Palace of Maat. Although he appears to have continued the decoration of Hatshepsut’s unfinished Red Chapel, the king eventually removed and dismantled the chapel, with the front and rear doors reused in an interior wall of the palace’s northern suite of rooms and the new corridor behind the sixth pylon. Some of the palace’s interior walls were removed, either by the king, or earlier, by Hatshepsut, to allow the emplacement of the central bark-shrine. The Red Chapel was replaced with a new granite shrine, of similar size and shape, and a new entrance portico was designed for the Palace of Maat.

“Possibly due to damage incurred in the wadjet hall from heavy rainstorms, Thutmose III began a total reworking of the space. A stone gateway was erected around the obelisks of Hatshepsut, completely encapsulating their lower portions. He ordered the removal of the wooden wadj- columns, intending to replace them with six sandstone columns in the north half of the hall and eight in the south. The interior walls of the court were covered with a skin of stone, obscuring the original statue recesses of Thutmose I. Before his death, it appears that the king only had time to roof the northern part of the hall with sandstone slabs, supported by his network of pillars, gateway, and court walls. Amenhotep II finished the work, raising the eight southern columns and their roof. Thutmose III raised his own pair of granite obelisks between those of Thutmose I and II in the festival court before the fourth pylon. The bases of these obelisks have been discovered bordering the east side of the third pylon.”

Karnak rams

Karnak Temple Under Amenhotep III

Elaine Sullivan of UCLA wrote: “Amenhotep III’s initial work at Karnak was a continuation of the activities of his father centered on the festival court of Thutmose II. He finished the decoration on his father’s shrine and likely added a northern door to the mud-brick precinct wall aligned with the hall’s north-south axis. Later, he dramatically re-envisioned the temple, tearing down the pylon erected by Thutmose II and destroying most of the festival court west of the fourth pylon. He built a new pylon to the east, the third pylon, using stone blocks of the removed structures in its foundation and fill. The western half of Thutmose IV’s peristyle, his calcite bark-shrine, the limestone White Chapel of Senusret I, the calcite chapel of Amenhotep I, and the loose blocks of the Red Chapel of Hatshepsut all fell victim to the renovations. [Source: Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Amenhotep III began construction on a new pylon (the tenth) to the south of Hatshepsut’s eighth pylon, extending the southern processional route towards the Mut Temple. While building was still at its beginning stages, he had two colossal statues of himself placed flanking the pylon entrance. With only a few courses completed on the pylon, the king must have died, as construction halted and was not to be resumed until the reign of Horemheb.

“Two other important structures built by Amenhotep III, both of whose exact location within the precinct remains unknown, attest to some of the less-documented aspects of the temple’s role in the city as a center of storage and production. Sandstone blocks from the “granary of Amun” have been found reused as fill in the towers of the second pylon. Contemporary Theban tomb scenes portray the granary as a structure with multiple rectangular rooms, each heaped high with mounds of grain. A second building, a shena- wab, was the site of the preparation of temple offerings. Parts of an inscribed stone door from this building were uncovered near the ninth and tenth pylons, and the shena-wab may have been located in the southeast quarter of the precinct.”

Precinct of Amun-Ra in the Late 18th Dynasty During Akhenaten and King Tut

Elaine Sullivan wrote: Amenhotep IV began his reign continuing his father’s projects at Karnak and he either added or decorated a vestibule for the third pylon. Quickly, however, the king shifted his focus to constructing a jubilee complex in east Karnak. A number of major structures were built using the new construction material of choice: small, easily portable sandstone (“talatat”) blocks. The location of most of the structures remains unconfirmed, but the “Gem- pa-Aten” was discovered east of the Amun-Ra precinct in the 1920s. The western part of the building, the only section so far substantially uncovered, formed a rectangular open court lined by a covered colonnade with square piers. The temple was enclosed by its own mud-brick enclosure. Huge androgynous statues of the king and his wife Nefertiti stood against each column. One of the king’s earliest temples, the “Great “Benben” of Ra-Horakhty,” and a second structure, the “Hut-Benben” (which, from its decoration, appears to have belonged solely to the queen), are posited to have stood near the “unique” obelisk of Thutmose IV. The “Rud-Menu” and the “Teny-Menu” (whose decoration suggests it included a royal podium, a “window of appearance,” and a series of gateways leading to an open-air platform for the worship of the Aten) may have bordered the “Hut-Benben” to the east. [Source: Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Sometime in his fifth regnal year, Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akhenaten and launched a fervent attack on the existence of gods other than the solar deity Aten. Amun was a special target, and his name and figure were effaced from temples throughout Egypt, including at Karnak. Shortly after, the king decided to leave the city of Thebes and move the center of cult, the royal residence, and his burial site to Middle Egypt, to a city he named Akhetaten (modern day Tell el-Amarna). The wealth of the Amun-Ra Temple at Karnak was diverted to building projects for the new city, and the temple itself was closed.

“After Akhenaten’s death, the boy king Tutankhamen reopened many temples and reinstituted construction and decoration projects at Thebes. A series of sphinxes originally inscribed by this king and his successor, Aye, line the processional way to the Mut Temple in the south. Initially anthropomorphic, the sphinx heads were replaced by Tutankhamen with carved heads of rams, and set up in this location. The male and female sphinxes seem originally to have represented Amenhotep IV/Akhenaten and Nefertiti, and they presumably originated in east Karnak.

“With the ascent of Horemheb to the throne, the Amarna Period officially ceased, and this ruler’s modifications of Karnak show a conscious attempt to eradicate the memory of Akhenaten and his family. Horemheb launched an assault against the Aten and within the first ten years of his reign he ordered the Karnak structures pulled apart, block by block, to be reused in the foundations and fill of his own building projects. The remains of these temples have since been found in Horemheb’s new sandstone constructions, the second and ninth pylons, as well as within the sandstone towers of the tenth pylon, which he completed atop the foundations of Amenhotep III. He also added an inscribed red granite gate to the tenth pylon entrance and a series of walls connecting pylons eight, nine, and ten, forming a new southern processional.

“The addition of the second pylon extended the Amun-Ra Temple farther west, and its construction would have necessitated the filling in of the existing T-shaped basin and canal fronting the temple. Perhaps this move westward was prompted by the river’s continuing shift away from the temple.

“Horemheb destroyed the court of Amenhotep II during his reworking of the southern approach to the temple, but he utilized many of the blocks to create a pillared structure set on a platform within the eastern wall of the court of the tenth pylon. The building, the “edifice of Amenhotep II,” was designed as a parallelogram, its axes adjusted to reflect the line of the processions passing before it. Despite the fact that Tutankhamen had dedicated his statuary and reliefs throughout the country to the traditional gods, Horemheb recarved many of the works of that king in his own name. At Karnak, this included the cartouches of Tutankhamen (and Aye) on the socles of the sphinxes along the avenue from the tenth pylon to the Mut Temple.

Seti I and Karnak’s Hypostyle Hall

Elaine Sullivan of UCLA wrote: “Sety I exploited the huge space created between the second and third pylons to establish a new locus for the celebration of important rituals and festivals. The pharaoh erected a massive hypostyle hall with 12 sandstone columns supporting a central nave and 122 sandstone columns filling the side aisles. It was roofed with sandstone, and light entered the hall through clerestory stone window grills. See Peter Brand’s “The Karnak Great Hypostyle Hall Project.” [Source: Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“That Sety I—and not any of his predecessors—originally constructed the hypostyle hall is supported by examinations of the building. Peter Brand observed that the earliest inscriptions on the clerestory windows and architraves of the central colonnade date to this king’s reign. By studying the methods by which the hall was decorated (which for these highest places was achieved before the mud-brick construction ramps were removed), Brand has shown that the original carving of the area must have been done immediately following the placement of the roof and clerestory blocks, thus during Sety I’s reign.

“During his lifetime, Sety’s artisans inscribed the northern half of the interior of the hall with beautifully carved relief scenes depicting cult activity. The vestibule of the third pylon, now enclosed within the hall, was altered. The smiting scenes of Amenhotep IV/Akhenaten on its north wall were covered over with stone blocks. On the north exterior wall, the king’s battles against numerous foreign foes were memorialized in a series of monumental relief scenes.”

Karnak frieze

Karnak Temple Under Ramesses II

Elaine Sullivan of UCLA wrote: “Ramesses II completed and altered Sety I’s unfinished decorative program on the walls and columns of the hypostyle hall. Battle scenes of the king were added to the hall’s southern exterior wall, paralleling the military decoration of his father on the north wall. The girdle wall enclosing the temple on its southern and eastern ends, built by Thutmose III, was now adorned with deeply carved relief scenes and inscriptions. [Source: Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“In the eastern section of Karnak, the king added a small shrine to the “unique” obelisk of Thutmose IV. The shrine, called “the temple of Amun-Ra, Ramesses, who hears prayers,” consisted of a gateway and pillared hall with a central false door. Two lateral doors led to the object of veneration, the “unique” obelisk. A number of the column drums used for the hall were clearly taken from an earlier Thutmoside structure, and there is some evidence that there had been a shrine in this location previously. The chapel seems to have functioned similarly to a contra-temple, as it was accessible to the public who visited for oracular judgments. Further east, along the temple’s east-west axis, Ramesses II added an entrance to eastern Karnak, marked by two red granite obelisks and a pair of red granite sphinxes.

“To the west of the Amun-Ra Temple’s main gate, the second pylon, Pinedjem may have placed a line of 100 or more criosphinxes on stone pedestals. This sphinx avenue is traditionally assigned to Ramesses II, whose titles are inscribed on the small statuettes between the animals’ paws. A new theory, however, argues that the sphinxes, which stylistically appear to have been carved under Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III, stood at Luxor Temple in the 18th and 19th Dynasties. When Ramesses II modified that temple, he usurped the statues and rearranged them before his new court at Luxor. According to the theory, they were only moved to Karnak in the 21st Dynasty, when Pinedjem added his own name and inscriptions to the socles. The exact length and terminus of this avenue remain unknown, as it was later reorganized when new constructions changed the front of the temple in the 25th Dynasty, but it likely extended up to the (later) first pylon, or to a quay beyond.”

Karnak Temple After Ramesses II

Elaine Sullivan of UCLA wrote:“Sety II was the next pharaoh to add significant structures to Karnak. In front of the second pylon (the west gate of the temple at the time), he placed a three-roomed quartzite and sandstone bark-shrine oriented perpendicularly to the north of the processional route. Its sanctuaries were dedicated to Amun, Mut, and Khons, and the barks of these gods would have paused here during festival journeys outside the temple. [Source: Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Building activity at Karnak at the start of the 20th Dynasty showed no signs of slowing down. Ramesses III added his own bark shrine to the area in front of the temple, opposite that of Sety II. This shrine took the shape and size of a small temple, including a small pylon, a court with colossal statue pillars, a hypostyle hall, and a sanctuary. Immediately north of the Amun-Ra Temple proper, Ramesses III renewed the inscribed stone gate of Amenhotep III in the mud-brick enclosure wall just north of the third pylon. To the south, Ramesses III built a temple to the child-god Khons. Study of the temple’s foundations showed that its design and construction began under Ramesses III, although some of the building elements may have been completed by later kings. The date and form of the earlier temple of Khons on this location is unknown, although reused blocks in the bark sanctuary suggest to some scholars that such a cult building was present at least by the reign of Amenhotep III. However, these blocks, as well as the sphinxes of Amenhotep III creating an avenue to the south of the temple, may instead have been quarried from the mortuary temple of that king on the west bank of the river.

“Ramesses IV continued construction on the Khons Temple, additionally inserting his own cartouches and decoration to the innermost areas. Within the Amun-Ra Temple proper, he drastically altered the appearance of the hypostyle hall by appending his cartouches to the columns, as well as carving new relief scenes on most of the shafts.

“But the later Ramesside kings could not maintain the feverish pace of construction sponsored by the wealthier New Kingdom rulers, and building activity tapered off sharply. Ramesses IX built the only significant structure, gracing the door to the southern processional route with a monumental inscribed gateway. The most substantial contributions of the last king of the dynasty, Ramesses XI, and Herihor, his “High Priest of Amun,” were the scenes and inscriptions in the Khons Temple’s forecourt and hypostyle hall.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024