Home | Category: Religion and Gods / Art and Architecture

TEMPLE OF KARNAK

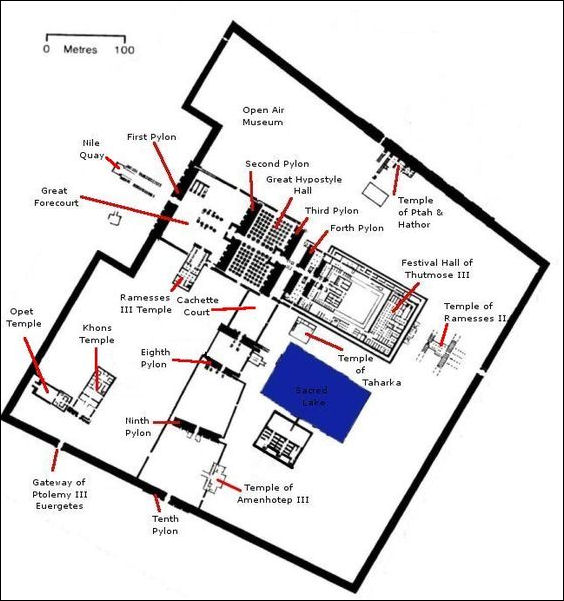

Karnak The Temple of Karnak (3 kilometers, 2 miles north of Luxor) ranks with the Pyramids as most amazing site in Egypt and by some estimates is the largest religious structure ever created. Over two millennia it was enlarged and enriched by consecutive pharaohs until it covered 247 acres of land on the Nile’s east bank. At its height it stretched over an area of one mile by a half a mile — about half the size Manhattan — and was like a city, containing its own administrative offices, palaces, treasuries bakeries, breweries, granaries and schools. "Karnak" is the Arabic word for fort. It used to be called Ipetesut — “most esteemed of places.”

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “ A place of pilgrimage for nearly 2,000 years, it dates back to around 2055 B.C. and continued to be used to around A.D. 100. It remains impressive today. To ordinary people in ancient Egypt it must have seemed like a place that only gods could have built. A cult temple dedicated to Amun, Mut and Khonsu, the Thebian Triad, it was the largest religious building ever constructed, covering about an area of 1.5 kilometers by 0.8 kilometers, and comprised of a city of temples built over 2,000 years. The area of the sacred enclosure of Amun alone is sixty-one acres and could hold ten average European cathedrals. The great temple at the heart of Karnak is so big that St Peter’s, Milan, and Notre Dame Cathedrals would fit within its walls. The Hypostyle hall, at 54,000 square feet (16,459 meters) and featuring 134 columns, is still the largest room of any religious building in the world.In addition to the main sanctuary there are several smaller temples and a vast sacred lake – 423 feet by 252 feet (129 by 77 meters). The sacred barges of the Theban Triad once floated on the lake during the annual Opet festival. The lake was surrounded by storerooms and living quarters for the priests, along with an aviary for aquatic birds. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

There are three main areas at Karnak are: 1) the Sanctuary of Amon; 2) the Sanctuary of Mut, 3) Sanctuary for Montu. Each is separated by a rough brick boundary and each has a main temple in the middle of the enclosure. Next to the main temples were sacred lakes where ceremonies were held. Unlike most other temples in Egypti, Karnak has two axes: one following the sun from east to west; and the other following the Nile from north to south. The largest structure contains the largest columns in the world.

Most of the structures at Karnak are part of the Sanctuary of Amon, which covers an area of about 60 hectares and is dedicated to Amon, the god of fertility and growth. To the south is the Sanctuary of Mut, which covers an area of about 9 hectares and is dedicated to Mut, the wife of Amon. Mut is symbolically portrayed in the form a vulture. To the north is a small Sanctuary for Montu, which covers an area of about 2½ hectares and is dedicated to Montu, the God of War.

The Temple Complex opens at 6:00am or 6:30pm. It is a good idea to arrive early and look around the grounds before it gets too hot and too many people arrive. When it does get hot you can seek refuge in the hypostyle hall, where there is ample shade even during the midday sun.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TEMPLES: HISTORY, TYPES, FEATURES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

COMPONENTS OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TEMPLES: SHRINES, DECORATIONS. MAMMASI africame.factsanddetails.com ;

STONE USED IN TEMPLES, MONUMENTS AND STATUES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

HISTORY OF KARNAK TEMPLE AND ITS DEVELOPMENT UNDER NEW KINGDOM PHARAOHS africame.factsanddetails.com

PRIESTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Karnak” by Elizabeth Blyth (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Temples of Karnak” by R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz (Author), Georges de Miré and Valentine de Miré (Photographers) Amazon.com;

“The Great Hypostyle Hall in the Temple of Amun at Karnak. Vol 1, Parts 2 and 3" by Peter J. Brand, Rosa Erika Feleg, William J. Murnane Amazon.com;

“The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2000) Amazon.com;

“Temples of Ancient Egypt” by Dieter Arnold (1997) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Temples” by Steven R. Snape (1996) Amazon.com;

“Gifts for the Gods: Images from Egyptian Temples” by Marsha Hill (2007) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture” by Dieter Arnold (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Construction and Architecture” by Somers Clarke and R. Engelbach (2014) Amazon.com;

“Building in Egypt” by Dieter Arnold (1991) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Masonry: The Building Craft” by Somers Clarke and R. Engelbach | (2023) Amazon.com;

“Architecture, Astronomy and Sacred Landscape in Ancient Egypt” by Giulio Magli (2013) Amazon.com;

“Architecture and Mathematics in Ancient Egypt” by Corinna Rossi (2004) Amazon.com;

History of the Temple of Karnak

Karnak was built to mark the birthplace of Amun, the greatest of all Egyptian gods. It was probably built on a pre-existing sacred mound. It was built with money that the pharaohs earned in taxes and booty brought back from military victories.

The temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak experienced over 1,500 years of construction, destruction, renovation, and expansion. Its origin is traced to the ascendancy of the Intef family. The first hard evidence of a temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak appears during the reign of Intef II (2112-2063 B.C.), third ruler of the Eleventh Dynasty of Egypt. It is thought he erected a small mud-brick temple, probably with a stone-columned portico, on the east bank for the god Amun-Ra. Evidence for this construction comes from a sandstone column found reused at Karnak that includes an inscription dedicated by that king. [Source:Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Work was carried out on Karnak for 2,000 years beginning in the 12th dynasty (around 2000 B.C.) of the Middle Kingdom when an early temple was established and successive pharaohs added their own shrines and gates. Construction of buildings continued through the Middle and New Kingdom periods, with most of the work done between the XVIII Dynasty and the end of the Ramses era. In the XVIX Dynasty, 81,322 people, including priests and peasants, worked on the temple of Amon. Construction of the main hypostyle hall began in 1375 B.C. under Amenhotep III, and was continued under Seti I, his son Ramses II and was finally completed under Ramses IV.

The temple originally had a roof, and the columns were once plastered and painted with heroic scenes from the pharaohs lives. But mostly what remains now are some carved hieroglyphics and symbols, embellished by graffiti from 19th century British and Egyptian soldiers and 20th century tourists.

One of the remaining wall inscriptions reads: "His Majesty exults at the beginning of battle, he delights to enter it; his heart is gratified at the sight of blood. He lops off the heads of his dissidents...His majesty slays them at one stroke — he leaves them no heir, and whoever escapes his hand is brought prisoner to Egypt." Another set of inscriptions describe the festival of Opet. The victories of Shoshenq I, a Libyan refereed to in the Bible as King Shishak, are immortalized on a relief at Karnak.

See Separate Article: HISTORY OF KARNAK TEMPLE AND ITS DEVELOPMENT UNDER NEW KINGDOM PHARAOHS africame.factsanddetails.com

Parts of Karnak Temple

The Temple of Amon is a long series of structures divided by six large walls and pylons (massive gates). Between these walls are large halls and courtyards, some with obelisks. The "Propylaea of the South" is an extension that includes the seventh, eight, ninth and tenth pylons.

Visitors enter the Temple of Amon on the Avenue of the Sphinxes (also called Avenue of the Criosphinxes) , which consists of a walkway sided by a parallel row of sphinx statues with ram heads. The rams represent Amon. Beneath the rams heads are small statues of Ramses II. The Avenue of the Sphinxes, leads to the first and largest pylon. Largely unadorned and built during the Roman-Greco Ptolemy era, the avenue is 113 meters wide and 15 meters thick.

At one time a long stone “dromos” — a walkway and procession route sided by sphinxes — connected Luxor with Karnak. The royal processional way, which connected the temple complexes of Karnak and Luxor, was once lined with more than 700 statues along its 1.7-mile length. These figures had the lion-shaped body of a sphinx, each topped with a ram’s head. In 2022, Archaeology magazine reported: Three huge carved ram’s heads were unearthed along the avenue. At least one of the newly recovered sculptures was associated with the pharaoh Amenhotep III, who ruled Egypt around 3,350 years ago. [Source: Archaeology magazine, January 2022]

The Ethiopian Courtyard (the first courtyard after the entrance to Karnak) dates back to the IX Dynasty. On the north side is an enclosed wall fronted by columns with closed papyrus capitals. In front of these are sphinxes commissioned by Ramses II. A giant column with an open papyrus capital is all that remains of the a massive pavilion of Ethiopian king Taharka. The pavilion was 21 meters high, had a wooden ceiling and was built to house sacred boats.

In front of the columns to the right is the Temple of Ramses III. On three sides of the interior of the temples are pillars fronted by statues of Ramses III with his arms crossedm holding a crook like the God Orisis. On the left side is the Temple of Seti I, dedicated to the chapels of the Thebes Triad: Amon, Mut and Khonsu. The white chapel of Semostris I and the alabaster chapel of Amenhotop I were rebuilt in the 1940s.

Temple of Amun

The Second Pylon (far side of the Ethiopian Courtyard) was originally decorated with two massive winged pyramids. Today there is a fallen statue of Ramses II. The large 15-meter-high statue is the Colossus of Pinedjem, a Pharaoh from XXI Dynasty. There is a small statue of a priest between his legs. Sometimes this statue is described as being Ramses II and his favorite wife Nefertari.

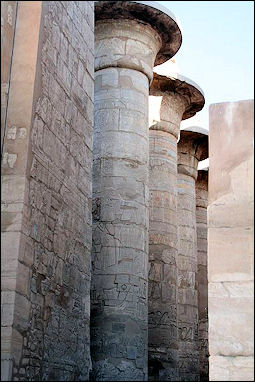

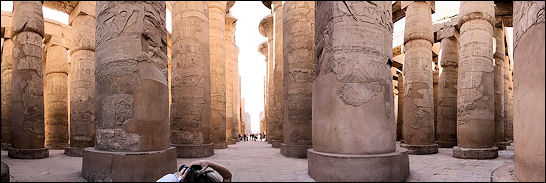

Hypostyle Hall of Karnak Temple

The Hypostyle Hall of Karnak — between the Second and Third Pylons, within the Karnak Temple complex, in the Precinct of Amon-Re — is a massive hall, with 134 massive columns, that measures 102 meters by 53 meters and and was once covered by a roof. Running down the center of the hall are 12 gargantuan open-papyrus-shaped columns that soar 70 feet into the air. These columns are the tallest stone columns in the world. They were raised in 1270 B.C. It is said that there is enough room on the top of each of these columns to throw a party with 50 people. The hall itself is large enough to accommodate Notre Dame cathedral.

On both sides of the papyrus columns are 122 smaller but still massive closed-papyrus columns that rise up 42 feet. The temple and the column are so massive and overwhelming many tourists that stand transfixed with their mouths agape as they try to take it all in. The climatic scene of the movie version of Agatha Christie's “Death on the Nile” was shot here as well as a chase scene from one of the Roger Moore James Bond movies.

It worthwhile spending some time in the hall to see how light and shade affect the columns as the sun moves across the sky. It is also worthwhile to get a guidebook of hieroglyphics and sit in the shade and try to decipher the texts written on the columns. Paintings remain on the undersides of the lintels that link the top of the columns. Look for a pillar with the carving of a scarab, the Egyptian symbol of fertility. Women who walk around this pillar seven times are expected to give birth shortly afterwards.

The Great Hypostyle Hall, covers 16,459 meters (54,000 square feet). The 134 massive columns are arranged in 16 rows. It is still the largest room of any religious building in the world. The 12 larger columns stand 24 meters (79 feet) high and have a circumference of (being 10 metres (33 ft). They line the central aisle, and with the other columns one supported a massive, now fallen, roof. The design was initially instituted by Hatshepsut, at the North-west chapel to Amun in the upper terrace of Deir el-Bahri. Some paint survives on the under side of the capitals and other places on some of the columns. The hall’s name refers to the hypostyle architectural pattern.[Source: Wikipedia, Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Karnak Hypostyle Hall

The hall was built entirely by Seti I (ruled 1294 to 1279 B.C.) who inscribed the northern wing with inscriptions. The outer walls depict his battles. Scholars previously thought the hall was constructed by Horemheb or Amenhotep III. Decoration of the southern wing was completed by Ramesses II, who he usurped the decorations of his father along the main processional walk ways. The south wall is inscribed with a record of Ramesses II’s peace treaty with the Hittites which he signed in 21st year of his reign. Later pharaohs including Ramesses III, Ramesses IV and Ramesses VI added inscriptions to the walls and the columns in places their predecessors had left blank. ^^^

The northern side of the hall is decorated in raised relief, and was mainly Seti I's work. The southern side of the hall completed by Ramesses II has a sunken relief although he used raised relief at the beginning of his reign. Ramesses II also usurped decoration of his father along the main north-south and east-west processional ways of the hall, giving the impression that he was responsible for the building. However, most of Seti I's reliefs in the northern part of the hall were left untouched. The outer walls depict scenes of battle, Seti I on the north and Ramesses II on the south. Although these reliefs had religious and ideological functions, they are important records of the wars of these kings. ^^^

In 1899, 11 of the massive columns of the Great Hypostyle Hall toppled over domino style because their foundations were undermined by ground water. Georges Legrain, who was then the chief archaeologist in the area, oversaw their rebuilding that was completed in May 1902. Later, similar work was done to strengthen the rest of the columns of the Temple to ensure the same thing didn’t happen again. ^^^

Columns of Hypostyle Hall

According to the Karnak Great Hypostyle Hall Project of the University of Memphis: The Great Hypostyle Hall is a forest of 134 giant sandstone columns in the form of papyrus stalks, with the 12 great columns in its central nave capped by huge open papyrus blossom capitals. The main east-west axis of the Hypostyle Hall is dominated by a double row of 12 giant columns. The 12 great columns are several meters taller than the 122 shorter closed-bud papyrus columns grouped on either side of the central aisle. The structural purpose of the twelve great columns was to support the higher roof of the clerestory in the central nave. [Source: Karnak Great Hypostyle Hall Project, University of Memphis ]

“All the columns in the hall represent papyrus stalks, and the 12 great ones have open capitals imitating the feathery blossoms of flowering papyrus.The diameters of the giant bell-shaped capitals are 5.4 meters (18 ft), wide enough to support 100 men. Natural papyrus stalks are not cylindrical but have three sides with ridges along each edge. The columns are round, but a slight ridge runs up each column like a vertical seam in imitation of the plant.

“Every inch of these columns has been inscribed by Ramesses II. Royal cartouches and Ramesses' other royal titles have been inserted nearly everywhere possible from the base of the shafts to tiny ones on the outer rims of the papyrus capitals. Two huge vertical cartouches below the scenes on each column face the processional axis, marking Ramesses II's claim to be the owner of the Hypostyle Hall. Ramesses II even placed his cartouches on the papyrus blossom capitals of the great columns 20 meters above the viewer at ground level. Ramesses II also decorated each of the twelve columns with two scenes depicting him offering to the gods. One scene faced west towards the main entrance of the temple and the other faced towards the main aisle so that the scene faced south on the northern row of columns and north on the southern row.

Decorations on the Columns of Hypostyle Hall

Hypostyle Hall columns

According to the Karnak Great Hypostyle Hall Project of the University of Memphis: “Ramesses II's interventions on the twelve great columns of the central nave are more extensive than for the 122 smaller ones. At the start of his reign, the twelve also had a simpler decorative scheme. The two main phases of his reliefs on these columns can be distinguished by the presence of absence of palimpsests of raised relief that he later converted to sunk. Reliefs lacking these palimpsests will have been carved in sunk relief later than those originally carved in raised relief. Initially, decoration on the great columns was limited to the triangular leaf pattern at the base of the shafts, two scenes midway up the shafts, a frieze of cartouches and cobras near the top and a vegetation motif with small cartouches on the wide papyrus blossom capitals. Large areas of the shafts remained undecorated. [Source: Karnak Great Hypostyle Hall Project, University of Memphis ]

“In the Great Hypostyle Hall, Ramesses II inserted additional stereotyped decoration above and below the scenes. Immediately above the scenes came an additional frieze of large cartouches resting on gold-signs and surmounted by a solar disk with ostrich plumes but lacking a frieze of cobras. Just beneath the scene was a pair of tall vertical cartouches facing the main axis. Extending to either side of these were parallels horizontal bandeau texts giving the king's Horus and cartouche names and titles. He inserted nearly identical bandeaux on the fourteen columns of the Luxor Colonnade Hall in the same position. Below this at Karnak was a small horizontal bandeau text with a speech of Amun and a string of the king's names and titles. Finally, Ramesses inserted a cobra and cartouche motif in the blank spaces between the triangular peaks of the leaf pattern at the base of the shafts. All of his later inscriptions on the twelve great columns were carved solely in sunk relief with the long form of his prenomen and the Ra-ms-s form of his nomen indicating that they were carved after his first regnal year but before his 21st year.

“Several decades later, Ramesses IV (ruled ca. 1153-1147 BCE) added his own cartouches over triangular leaf patterns at the base of the shafts. These are difficult to read because this king changed the spelling of his name and recut these inscriptions. Later still, Ramesses VI (ruled ca 1143-1136 BCE) took credit for these by placing his own name inside the cartouches. Plaster was used to cover the earlier versions each time. Most of this is gone, leaving a confusing jumble of hieroglyphs. In some places the plaster remains, testament to a Pharaonic "cover-up."”

Karnak Obelisks and Festivals

After the Third Pylon visitors come to the obelisk of Thumosis I. It is 23 meters tall and weighs 143 tons. Other obelisks were located here but they are now gone. After the Forth Pylon is the obelisk of Hatsheput. It is 30 meters high and weighs 200 tons. Queen Hatsheput reportedly spared no expenses and poured in "as many bushels of gold as sacks of wheat" to get the obelisk completed.

There were once six large obelisks and two smaller ones in this area. Among these are the Lateran Obelisk, now in Rome. The great obelisk at the Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak is nearly 100 feet high and weighs about 323 tons — about the same as a 747 jumbo jet. The Red Chapel of Queen Hatashepsut (1505-1484 B.C.) is Karnak’s largest chapel at 100 square meters. Comprised of huge black granite and red quartzite slabs, it stood for only 20 years before it dismantled by her son-in-law and used for another structure. In 1996, it was reconstructed.

The Opet Festival in Thebes was held annually during the season of Nile flooding. It celebrated the annual reunion of the Thebean Triad: the great god Amum, his wife Mut and their son Khonsu. Details of the ceremony are carved in a relief in the processionary colonnade in Luxor Temple.

The ceremony may be been developed by Queen Hatshepsut. Opet means "southern sanctuary," a reference to Luxor Temple, the southern temple in Thebes. The Opet Festival began on the nineteenth day of the second month of the flood (the end of August). Earlier versions of the festival lasted 11 days. By the 18th dynasty (1550-1298 B.C.) the festival was the main event on the Egyptian calendar. In Ramses II's time it continued for 27 days. The festival itself may have lasted into the Roman era.

The Egyptians believed that towards the end of annual agricultural cycle the gods and the earth became exhausted and needed a jolt from the chaotic energy of the cosmos to get the process going again. To achieve this goal magical regeneration was invoked at the annual Opet festival at Karnak and Luxor. Lasting for 27 days, it was also a celebration of the link between pharaoh and the god Amun. The main even t was procession that began at Karnak and ended at Luxor Temple, 2.4 kilometers (1½ miles) to the south. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

See Separate Article: OPET FESTIVAL OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Temple of Amun-Ra-Who-Hears-Prayers

Laetitia Gallet wrote: The eastern temple of Karnak known as “Temple of Amun-Ra-Who-Hears-Prayers” was partly built and entirely redecorated between year 40 and year 46 of the reign of Ramses II; it was located in an area devoted to the personal piety from Thutmose III until the reign of Ptolemy VIII. The masonry has revealed that the temple hides previous structures. This former edifice could be the work of Horemheb. The columns of the hypostyle hall, which have probably been in place since the Thutmosid Period and were transformed by the Ramesside intervention, suggest also that a Thutmosid structure was still there. 4Dm nHt is the principal epithet — but not the only one — which indicates that the king as the god listens to the prayers in this sector of the Karnak Temple complex. Some tenuous indications suggest that divine justice, as corollary of the listening of the prayers, could have been applied in the temple by means of a processional bark before the Ptolemaic Period; during the reign of Ptolemy VII, there are indications that justice was administered in the temple. [Source: Laetitia Gallet, Collège de France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ]

“The Temple of Amun-Ra-Who- Hears-Prayers or the Eastern Temple is located at the back of the architectural complex of Karnak, within the mud-brick enclosure wall of the 30th Dynasty, approximately 400 m from the First Pylon. Its actual entrance, which faces east, lies at a distance of less than 50 m from the Eastern Gate to the Karnak complex, while the center of the monument, the Unique Obelisk (also the Lateran Obelisk), is approximately 20 m from the contra-temple of Thutmose III (see Karnak, contra-temple). The entrance is fronted by a colonnade dating to the reign of Taharqa. North of the north wall lies an unexcavated area of approximately 45 x 45 m, which comprises several mud-brick structures. This area with earth-filled ruins is higher than the temple, and the mound leans against the temple wall at its northwestern corner. Surprisingly, this heaped mound of soil has never been excavated and preserves some of the original landscape from the time of the first discovery of the site.

In its present state the temple, with a length of slightly over 30 meters, consists of three distinct parts. 1) A long entry portal that has the form of a corridor, which pierces the remains of a massive mud-brick wall (situated along the same line as the temple’s eastern enclosure wall during the 18th Dynasty), constructed upon curved foundations. Its appearance evokes that of a pylon, also because the door jambs made of layered sandstone are sloped. 2) A peristyle court with eight “wadj”-columns and two Osirian pillars, distributed between the southern and northern half of the court. Two gates open towards the exterior of the lateral walls. 3) A hypostyle hall, which is entered from the peristyle court through an axial door and two open lateral doors in the interior wall. The room has four “wadj”-columns and protects the foundation stones of the Unique Obelisk at the axis and at the very end of the monument. Two small lateral chambers line the original emplacement of the obelisk.

Walls and Columns of the Temple of Amun-Ra-Who-Hears-Prayers

Laetitia Gallet wrote: The Temple of Amun-Ra-Who-Hears-Prayers displays a number of strange architectural features: the limited width of the lateral walls (less than a meter for walls that would have been 7 m high); the use of thin “plates” of stone only 10 to 15 centimeters deep; sections of bulging stone, protruding 35 to 40 centimeters from the surface of the sandstone in several places of the lower part of the walls of the court (inside and outside); and finally the door jambs of the lateral gates, which have a thickness twice that of the usual ratio during the New Kingdom. All these remarkable features can be accounted for by one explanation: the walls of Ramses II were originally thicker. They consisted of two headers and two stretchers, which would have formed the interior of the wall. They were revealed when the surface of the wall was cut back to remove the sunk relief of earlier date. The “plates” are thus scraped down blocks, and in some places they have fallen out: either the back of the neighboring block has become visible in the masonry or the empty space was filled with mortar. The unusual thickness of the lower part of the walls inside the court, i.e., the stone extrusions, can also be observed on the external faces of the walls of the peristyle court, giving the impression that the temple was erected on a podium. This phenomenon is difficult to explain, unless we suppose that the wall was originally thicker. The present size of the door jambs also reflect the scraping of the original wall surface, but to a lesser extent: the door jambs were decorated in raised relief, which required much less leveling to prepare the stone face for the Ramesside decoration. [Source: Laetitia Gallet, Collège de France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ]

“Although unrefined masonry, reuse, and pockmarked walls are a very usual phenomenon during the Ramesside Period, the present case appears to be somewhat different. Ramses II probably used an existing structure and maintained the layout, but scraped down the more massive walls for his own decoration. This scenario seems corroborated by the dedicatory text on the monument (on the external face of the north wall), which specifies that “the temple of the upper (eastern) gate was remade anew.” Furthermore, tracks of an ancient wall predating the Ptolemaic one have been noticed north of the hypostyle hall. Therefore, it seems possible to suppose that a previous temple existed with a plan somewhat similar to what is extant today, at least for the peristyle court and perhaps the hypostyle hall.

The four columns of the hypostyle hall are “wadj”-columns, reusing the drums of “jwn”- columns. The old polygonal column shafts were installed on earlier bases, which already had traces of placement or guidelines for other, no longer extant, pillars. The new polygonal shafts associated with these ancient bases (and masking the prior guideline) were never decorated. The columns were uninscribed for a sufficiently long period to have been covered with cupules (small hollow scrapes, to collect stone powder for magical purposes) almost everywhere on their surface. Ramses II then abraded the circular collar of the lower drums and the ridges of each polygonal column, replastering them to obtain the curve of a wadj-column, filling the cupules, and inscribing his texts. After performing this change, the former guideline on the column bases reappeared.

“The imposing wadj-columns of the peristyle court, a completely Ramesside concept, are made of half cylinders and roughly hewn blocks smoothed over with mortar (in some areas over 10 centimeters thick). Polygonal drums, with 16 cut planes, identical to those of the hypostyle hall, are exclusively and intelligently used in the narrow parts of the column shafts: under the capital and the lowest drum, which corresponds to the part where the shaft is constricted. It would have been necessary to plaster them to a larger thickness if they had been indiscriminately employed at a wider part of the column. Moreover, the ribs were not leveled and the cupules not filled up: it was not a necessity because the entire column was supposed to be covered in a generous layer of plaster, and the ribs and cupules would actually have facilitated the adhesion of the plaster.

“The extremely heterogeneous masonry of the Osirian pillars in the peristyle court — without any equivalent — indicates that the method was the same as that used for the walls: carving, similar to what was done to the “plates,” caused the face of the southern Osirian figure to be like a mask, which was about to fall before the restoration. Very thick plaster was found in many parts as medium of sculpture. The hands of the colossus were, for instance, entirely made of plaster. Furthermore, small blocks were used, and the north face of the base of the north Osirian pillar has stone bulges. Here are some of the features showing that, in this particular case, it seems impossible to consider a scenario in which Ramses II would have created pillars with reused blocks coming from another place. Considering that the workers had to cope with material that was already in place, as in situ masonry, and had to carve the new shape from a thicker structure, allows us to explain why they did not reuse stones in a more adequate way.

After the Fifth and Sixth Pylon at Karnak

After the Fifth and Sixth Pylon is the Sanctuary of the Sacred Boats, the Festival Hall (also known as the "Temple of Millions of Years"), the large ceremonial Hall of Tuthmosis III and the Temple of Tuthmosis III. All of these buildings were covered by a large roof. Further on are the Temple of Ramses II and the Portal of the East. To the north of Portal of the East are the Osiris Chapels.

The Fifth Pylon was raised by Tuthmosis II and the Seventh Pylon was raised by Tuthmosis III. The Festival Hall is a hypostyle hall painted red to imitate wood. It included a row of 32 pillars. Some have paintings from the A.D. 6th century that are in fairly good condition. They were made by Christian monks. In the Sanctuary of the Sacred Boats are reliefs that still contain centuries-old pigments. In 1996, archaeologists began reconstructing the chapel of Thutmosis IV using a crane from a bridge project to lay the 35-ton ceiling slabs.

Sacred Lake (outside the main hall) was used for purification and was regarded as the dominion of Amon. Measuring 120 meters by 77 meters, it is surrounded by buildings, storehouses, and priest's homes. In ancient times there was an aviary for aquatic birds. Sacred ducks and geese lived in the lake whcih also provided fresh water for purification rituals. Priests purified themselves in the morning in the waters before going about their duties.

Today the Sacred Lake surrounded by restaurants and souvenir stands. Nearby is a large granite scarab dedicated to the Khepr by Amonosis and offering storehouses. To the east of the Sacred Lake is a row is a viewing stand, used to watch the Light and Sound Show at night. From here there are good views of the entire Karnak Complex.

Propylaea of the South (extending from the south of main temple) is in the process of being restored. It includes the seventh, eight, ninth and tenth pylons and several colossal statues. Large portions have completed. Judging from the numbers of pieces laying around a lot of work still needs to be done.

Next to the main hall are rows and rows of piled stones. These are remnants from a temple built by Akhemtan. In the 1960s a journalist photographed 30,000 decorated blocks and with the aid of a computer attempted to piece them together like a jigsaw puzzle. The Portal of the South, Temple of Khonsu and Pylon of the Temple of Opet are located on a rise with good views of the Propylaea of the South.

The Sanctuary of Mut (one kilometer south of the main temple) includes the Portal of Ptolemy II Philadelph, Temple of Mut, Great Sacred Lake, Temple of Ramses III and Temple Amonosis III. Sanctuary for Montu (north of main temple) embraces the Temple of Montu, Temple of Maat, Portal of the North, and a Ptolemaic Temple.

temple complex at Karnak

Poem on the Battle of Kadesh — Inscribed at Karnac

The Battle of Kadesh has been detailed in the poem of Pentaur, the son of Ramses III. In the poem, Ramses II is exalted as a great warrior and leader. The poem was inscribed upon the walls of five temples, one of which was at Karnak, on orders of Ramses II. Accompanying poem on these walls were enormous engraved illustrations of the scenes of the poem. Many commemorate the exploits of Ramses II in his battle with the Hittites. In the poem the Khita is the Egyptian name foe the Hittites.

Pen-ta-ur’s Victory of Ramses II Over the Khita: (1326 B.C.) reads

“THEN the king of Khita-land,

With his warriors made a stand,

But he durst not risk his hand

In battle with our Pharaoh;

So his chariots drew away,

Unnumbered as the sand,

And they stood, three men of war

On each car;

And gathered all in force

Was the flower of his army,

for the fight in full array,

But advance, he did not dare,

Foot or horse. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. III: Egypt, Africa, and Arabia, trans. W. K. Flinders Petrie, pp. 154-162]

See Separate Article: RAMSES II, THE HITTITES AND THE BATTLE OF KADESH africame.factsanddetails.com

Inscriptions and Function of the Temple of Amun-Ra-Who-Hears-Prayers

Laetitia Gallet wrote: An inscription on the “Upper Gate,” barely legible today, seems to specify both Ramses II and the god “sDm nHt”. Five other attestations of the expression “who listen(s) to the prayers” exist in the temple: four referring to Amun-Ra (one from the Ramesside Period, three on Ptolemaic monuments), and one specifically mentioning Ptolemy VIII. More than a change in function, deviating from the original, this epithet given to both king and god seems to indicate an assimilation, a process whose existence we knew about, but which is echoed particularly in this part of the Karnak complex: the visiting believers are greeted by two Osirian pillars with the face of Ramses II, whose flesh is painted blue, as in most reliefs representing Amun. [Source: Laetitia Gallet, Collège de France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ]

“In the eastern sector of Karnak, “sDm nHt” may have indicated the popular veneration of a colossal statue of Thutmose IV. Based on a text of Thutmose III, we know that the sanctuary behind the statue was named, right from its construction onwards, “exact place of hearing” or “exact place of the hearing ear”. It is, then, this last designation, which brings a scene from the temple of Khons to mind, where Herihor is depicted before the Unique Obelisk and a building called “MsDr-sDm”, “the hearing ear”.

“While having functioned as an independent cult place for a thousand years, it seems that the Eastern Temple also served as a type of antechamber between the believers and the heart of “He-Who-Hears-Prayers,” which was, as the name specifies, “the exact place.” Before the Ptolemaic era, the side gate of the peristyle court opened towards the exterior and may have been meant to regulate the circulation of persons, guiding them towards the contra-temple at the back of the Unique Obelisk. During the reign of Ptolemy VIII, when the small gates appear no longer to have functioned, the temple still had the function of antechamber for the listener, but more as a space of negotiation, where one would halt than a route or corridor. This seems to be devised by the pavement and the barriers at the entrance of the peristyle court, related to the location of the inscriptions of Ptolemy VIII opposite these.

model of Karnak

“The divine justice is the corollary of the listener, and it seems that by intervening in the axial gate leading to the hypostyle hall, Ptolemy VIII sought to create a “rwt dj MAat”, “gate where justice is done”. Although none of the extant inscriptions mention the term, the identification of the structure as a “rwt dj MAat”, a name that furthermore covers a function, is strongly suggested by the texts in the lower courses of the gate, which are similar to the texts on the Gate of Evergetes, or the “Mht” of Edfu. Both texts contain the double theme of the benevolence of the god and his power to sanction, mentioning among other epithets a god “with open ears,” “rewarding the true speech and punishing the lie.” The system of barriers at the entrance of the peristyle court could have contained the believers or the accused at a respectable distance of the gate and the divinity. They could also have played a role in the taking of oaths and pledges.

The presence of “Nehemet-awy: (“The one who protects the despoiled”) and Rattawy (whose role in taking an oath is well known for the Late Period) in the iconography could be an indication of this. It is possible that oracular activity took place here. “The performance of justice has already been attested in the eastern sector of the Karnak complex since the times of Ramses II. Papyrus Berlin 3047 contains an echo of a lawsuit presided by Bakenkhonsu near a gate, which was called “Maat is satisfied”. This gate must have been situated east of the “Upper Gate”. “Divine justice also seems to have been exercised in this area during the New Kingdom. We can legitimately consider that this monument, with its emphasis on listening, could have been related to the processional bark (boat), especially in a period in which this was the primary instrument for oracular activities.

A graffito of a bark has been engraved on the base of the southern Osiriac pillar. If we distinguish the pedestal, with the shield, and bulging sails of the naos, one could not say whether bow or stern are falcon headed (hieracocephale) or ram headed (criocephale). In contrast, the outer wall and the door frames of the temple contain many more figural graffiti representing, without ambiguity, the Ram’s head of the bark of Amun. Although in themselves difficult to date, these graffiti seem, nevertheless, to reflect real facts: the departure of a bark. Ordinary people would not have had access to the temple precinct, or the passage of the bark, with exception of the outer areas of the temple. Only particular personnel, such as scribes and priests, were allowed to penetrate in to the antechamber of listening. The jambs of the “Upper Gate” remind us that everyone beyond these gates was supposed to be cleansed and purified. This enriched imagery at the entrance of the peristyle court, near the gates, represents small cult devices, modest but well-cared for and probably repaired. Their placement is related to the individual piety of the temple personnel that was authorized to circulate through the lateral entrances to the court.

Karnak Settlements

Marie Millet of the Louvre and Aurélia Masson of the British Museum wrote: “At Karnak, in addition to the well known temples, there is another type of architecture: the settlements, “comprised mainly of mud brick buildings. “They are a testimony of the everyday life of the ancient Egyptians for which remains have been found throughout all of the temples of Karnak. Continuous occupation from the First Intermediate Period until the Late Roman Period is well attested at different locations in the complex of Karnak. Settlements are easily recognizable by their use of brick, especially mud-brick. The artifacts and organic remains found during new excavations of settlements give us a good idea of the inhabitants and their daily life. [Source: Marie Millet of the Louvre and Aurélia Masson of the British Museum, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Karnak is understood as the whole area occupied by the three temenoi: Montu, Amun-Ra, and Mut—by extension all of the current archaeological area. The notion of settlements can be defined by the construction material, the mud-brick, which was used for several types of buildings such as houses, workshops, and storehouses. .. We can find as many settlements outside the religious complex as inside. There are two categories of settlements, either they are associated with the town of Thebes (with regard to the “city of Thebes”) or they are linked to some institutional installations, cultic and royal (warehouses, workshops, priests’ houses, palaces, etc.). Both types can be found within the same settlement and, as they can show the same kind of architecture, it is sometimes hard to distinguish them. In the analysis of Karnak settlements, it would be helpful to erase the actual precinct walls to understand the topography throughout the evolution of the site .

“The southwest sector of the Amun Temple, which corresponds to the area of the Opet and Khons Temples and to the courtyard between the ninth and tenth pylons, was used for cultic activities from the middle of the 18th Dynasty until the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.). However, between the Middle Kingdom and the beginning of the 18th Dynasty, and later during the Roman and the Late Roman Periods, the architecture was civilian in nature. This was confirmed by excavations in the courtyard of the tenth pylon. Recently, excavations in front of the Opet Temple have provided new evidence for a settlement. A residential or artisanal quarter occupied this sector until the 13th Dynasty. Later it seems to have been associated with cultic buildings.”

Settlements Area in Karnak

Marie Millet and Aurélia Masson wrote: “At north Karnak, settlements dating from the Middle Kingdom until the 17th Dynasty were uncovered under and outside the treasury of Thutmose I. This quarter is characterized by houses and workshops. From the 17th Dynasty, no more than traces of walls were preserved. During the New Kingdom, when the Temple of Karnak was enlarged, the old town was probably partially abandoned as a living area and was covered by official and religious buildings. A renewal of private construction took place after the end of the New Kingdom. From the Third Intermediate Period until the Roman Period, domestic and craft settlements occupied the zone east of the treasury and a limited area within the treasury itself. To the west of Montu’s precinct, a sector including Late Period installations in mud-brick was cleared. The buildings may correspond to houses or to structures linked with nearby chapels. Other Late Period mud-brick structures were discovered in the northwest area of the Temple of Amun. They were located outside the temenos before the precinct was built by Nectanebo. The walls with deep foundations and the cell plan demonstrate their likely use as storerooms. This type of building may have been used in conjunction with cult activities, like the “storeroom” overhanging the chapel of Osiris Neb-Djefau. Buildings presenting such architectural characteristics are present in several places inside the Temple of Amun. The whole district was ravaged by fire in the Late Period. No archaeological remains of a later important occupational phase were uncovered in these areas. Nevertheless, Demotic papyri attest to the existence of a residential quarter in the vicinity of north Karnak, called “the House of the Cow,” which was mainly inhabited by necropolis workers and personnel of the Amun Temple. [Source: Marie Millet of the Louvre and Aurélia Masson of the British Museum, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“At east Karnak, the Temple of Akhenaten was built on domestic structures, dating to Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period phases. Further settlement remains have been found under the Osirian tomb and the chapel of Osiris Heqa-Djet in the temenos of Amun. This settlement, characterized by thin walls and silos, may be earlier and date from the First Intermediate Period to the Middle Kingdom. Even though these structures were found in the actual temenos of Amun, defined by the Nectanebo enclosure wall, they were outside the cult area during the time of their occupation. New Kingdom settlements at east Karnak are only known from residential or storage structures dated to the Ramesside Period. Several architectural phases of the Late Period were discovered too. Between the end of the seventh and the beginning of the sixth century B.C., the area consisted of houses and workshops. The buildings of the 26th - 27th Dynasties show substantial foundations, which could support several floors; their plan presents a cell structure. These features tend to be considered an indication of use for storage; however, this type of architecture seems to have fulfilled many other functions . Occupation continued until at least the 30th Dynasty. During this period some reconstructions and modifications were made, but in general they followed the previous structures. The building called Kom el- Ahmar, located to the southeast and always outside the precinct of the Amun Temple, had the same characteristics, thick walls with deep foundations. This structure, whose function is not determined, was used from the Late Period up to the Ptolemaic Period. Deep trenches helped expose several architectural phases of domestic nature from as early as the 18th Dynasty until the Third Intermediate Period.

“Other excavations have revealed settlements in close proximity to the east side and southeast corner of the sacred lake in the Temple of Amun. The first remains were discovered in this area at the beginning of the twentieth century; mud-brick walls associated with large quantities of ceramics as well as statues from the 13th Dynasty were brought to light. ... Occupation was almost uninterrupted from the First Intermediate Period until the Roman Period. From the First Intermediate Period to the 17th Dynasty, civil occupation was continuous. This area, considered a part of the town, is characterized by workshops and houses. The workshops seem essentially to have been in an open area and included bakeries/breweries, but also a pottery workshop(s), a slaughterhouse, facilities for manufacturing stone tools, beads, etc. With the construction of an enclosure wall during the 18th Dynasty, the sanctuary of Amun and its surroundings were completely reorganized. From this point on, the settlement was closely linked to the activities of the temple. A housing quarter was established on the east bank of the sacred lake, within the limit of the enclosure wall. Apart from a hiatus at the end of the Late Period, we can follow this quarter’s evolution from the Third Intermediate Period until the beginning of the Roman Empire. The inhabitants are clearly identified as priests, since door frames, stelae, and numerous seal impressions bearing the titles of priests were discovered. The priests used these houses during their cultic service, when they were isolated from their families. It was an elite community, whose needs—such as rations, furniture, and so on—were met by the Temple of Amun. During the Ptolemaic Period, the priests lived among the craftsmen: many testimonies of craft activities were uncovered (sculpture, a faience workshop, evidence of metallurgical activity, etc.).

“South of the Amun-Ra precinct in the area of the Mut Temple, mud-brick structures dating to the Middle Kingdom through the Second Intermediate Period have been found, most certainly belonging to the town of Thebes. Some remains of the Late Ptolemaic and Roman Periods were identified as living and/or large storage and cooking areas. “To the west of Karnak, no remains of the Middle Kingdom have been observed, which could indicate the limit of the habitable area. This limit could be located in the vicinity of the third pylon of the Amun Temple. Later, with the migration of the Nile, the temple developed westward. Civil installations, mainly houses, appeared in front of the first pylon at the end of the third century B.C.. The quarter surrounding the chapel of Hakoris was reconstructed many times until the fourth century CE. These successive installations followed similar orientation and outlines. Current excavations by the Supreme Council of Antiquities in the western outskirts of the Temple of Amun have uncovered new settlements from the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods

Architectural Features and Material Used in Karnak Settlements

Marie Millet and Aurélia Masson wrote: “Settlements use brick, especially mud-brick, as their primary building material. Unfired brick is used in the construction of the houses themselves, but also in different types of equipment like silos, ovens, cooking areas, etc. Red brick was commonly employed since the Roman Period in the Karnak settlements. However, tests indicated that most of the bricks of the Kom el-Ahmar building were lightly fired prior to their use. Mud-brick is composed of Nile silt mixed with sand and/or straw. In general, brick composition and size do not determine the dating and purpose of the settlements’ architectural remains. Moreover, reuse of mud-brick can occur: House A, one of the houses in the priests’ quarter dating to its Ptolemaic phase, is made of bricks from the New Kingdom enclosure wall. [Source: Marie Millet of the Louvre and Aurélia Masson of the British Museum, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Stone is used for some elements of construction like doorjambs, pivot holes, column bases, and clerestory windows (openings high in the wall with stone lattice work). The use of stone often indicates an official building. Although evidence of wood is scant, it was used for roofing, staircases, doors, columns, and shelving. East of Karnak, J. Lauffray discovered buildings with two colonnades with stone bases and probably wood columns. Reuse of a column base as a pivot hole in a workshop was observed in the new excavation southeast of the sacred lake.

“In the village of Deir el-Medina, some colored coating has been preserved on the walls, but until now, only white coating has been found in the Karnak settlements, sometimes just a coating in mud to smooth the walls. The floors were generally a hard-packed surface. Paved floors, mainly in sandstone, are found in some late buildings during the first millennium B.C.. They were usually used in a single room, especially, but not exclusively, when some culinary activities were involved. This is the case in some houses in the quarter of priests: paved rooms, located between the enclosure wall of the New Kingdom and the back of the houses, were used as a kitchen.

“The buildings could have been more than one story high, since staircases are a common feature in Karnak settlements. Some staircases may only have led to a roof. Thanks to archaeological observations, we can assume that some houses, magazines, and workshops had a basement. Modest structures, especially in open areas, were built without foundations.”

Karnak Settlement Artifacts and What They Say About Its Inhabitants

Marie Millet and Aurélia Masson wrote: “The artifacts found during the 2001 - 2008 research project east of the sacred lake give a good idea of the inhabitants and their daily life. Sieving all the contexts through a fine sieve (1 mm mesh) provided a wealth and variety of material scarcely seen in Theban settlements. Ceramics represent the most common type of artifact. Typologies were established that enabled the dating of the buildings and installations. The majority of the ceramic material belongs to ordinary vessels, which were used for the transport and storage of liquids and commodities, for culinary activities, and the consumption of food. Ceramics for cultic use, such as incense burners, are very common in the priests’ quarter, especially in the contexts of Late and Ptolemaic Periods; it is likely though that they were often only used for domestic purposes. [Source: Marie Millet of the Louvre and Aurélia Masson of the British Museum, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“As expected in the Theban region, the imports are rare but originate from various regions: Cyprus, the Levant, Greece, the Aegean region, and Nubia. A variety of stone tools, particularly made of silex, are commonplace within the sector, such as work tables, pebble grinders, flint blades, and perforators. They attest to culinary and craft activities. Furthermore, some seal impressions were also found, which have given us the names and titles of inhabitants of the town of Thebes and people working in the sanctuary of Amun. Titles range from the “High Priest of Amun-Ra” (Hm-nTr tpy n Imn-Ra), “Prophet” or “Divine Father of Amun” (Hm-nTr/jt-nTr n Imn) or other deities, to those responsible for the storerooms (xtm bjty jmy-r xtmt). Hence, settlements in Karnak represent an interesting testimony to the social classes allowed to live in the sanctuary and its neighborhood. Other categories of objects give information about daily life: for example, games, like clay toys or counters, or jewelry made of faience, clay, semiprecious stone, or metal. Objects can also specify the social class of the inhabitant. Luxurious or elegant objects werefound in the settlements within the sanctuary. It seems that priests, or craftsmen working for the temple, had access to objects from the temple storerooms.

“The study of the food remains carried out in the recent excavations east of the sacred lake indicates a great gap between the diet of the people living in the sanctuary and those who lived outside. Priests and craftsmen working in the temple ate meat from animals usually sacrificed to the deities, such as beef and goose, confirming Herodotus’ testimony. The other people, at least during the Middle Kingdom, mostly ate pork and fish, food that was not admitted inside the temple, as pork and fish were very often considered too impure to sacrifice and therefore excluded from the diet of the priests. In Elephantine, pork and fish seem absent from a house linked with cultic activities related to the Khnum Temple, whereas they are present in the rest of the town. In the case of the quarter of priests, the multidisciplinary approach of the study has revealed that the inhabitants profited from the divine offerings. Nevertheless, they received these products raw, as their houses were sufficiently equipped for culinary activities with grindstones and pebble grinders for the cereals and seasoning, various categories of ceramic vessels for the preparation and the consumption of food, and ovens and hearths to cook the food. Storage facilities were, on the other hand, very scarce. This might indicate a dependence of this quarter on the offering magazines. The recent excavations demonstrated that offering magazines stood on the southern bank of the sacred lake, in the neighborhood of the quarter of priests, at least since the Third Intermediate Period, if not the New Kingdom.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024