Home | Category: Education, Health and Transportation

DOCTORS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

court physician Niankhre

The Egyptians were one of the first people to have practicing physicians. The oldest known physician, Imhotep, lived around 2725 B.C. He was also a high official, the designer of famous Step Pyramid and astrologer who achieved such high status that he made into a god. The Egyptians had dentists and obstetricians. Egyptian physicians often specialized in a specific part of the body, such as the stomach, eyes and bowels.[Source: Page of Egyptian Medicine ~]

Egyptian doctors were fairly knowledgeable about the human body. They studied the structure of the brain, and knew that the pulse was related to the heart. They could cure many illnesses and set broken bones. There is evidence Doctors in Ancient Egypt underwent years of training at temple schools in areas such as interrogation, inspection, and palpation. Some surgery was done. Skulls with holes in them have been found. ~

In the fifth century B.C., Herodotus stated that the Egyptians had doctors who specialised in particular areas of the body, and Egyptian physicians appear to have been famed in other parts of the ancient world. Like modern doctors, Ancient Egyptian doctors gave out prescriptions for medicines. One from the Ptolemaic era, written in Greek, contained lead monoxide as one of its ingredients. [Source: Joyce M Filer, BBC, February, 17, 2011 |::|]

Even during the Old Kingdom of medicine was already in the hands of special physicians called “j snu”. We still know the names of some of the royal body-physicians of this time; Ni-Ankh-Skhmet, the “chief physician of the Pharaoh," served the King Sahure, while of somewhat earlier date perhaps," are Ra'na'e'onch the “physician of the Pharaoh," and Nesmenau his chief, the “superintendent of the physicians of the Pharaoh. " [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The priests also of the lioness-headed goddess Sekhmet seem to have been famed for their medical wisdom, whilst the son of this goddess, the demigod Imhotep, was in later times considered to be the creator of medical knowledge. These ancient doctors laid the foundation of all later medicine; even the doctors of the New Kingdom do not seem to have improved upon the older conceptions about the construction of the human body. We may be surprised at this, but their anatomical knowledge was very little — less than we should expect with a people to whom it was an everyday matter to open dead bodies.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HEALTH OF ANCIENT EGYPTIANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIFE EXPECTANCY OF ANCIENT EGYPTIANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN VIEWS ABOUT HEALTH africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DISEASE IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MALARIA, CANCER, PLAGUES factsanddetails.com ;

HEALTH PROBLEMS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: INJURIES, ANEMIA, CLOGGED ARTERIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

HEALTH CARE IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com ;

MEDICINES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Medicine and Healing Practices in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David and Roger Forshaw (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Medicine” by John F. Nunn (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Medicine of the Ancient Egyptians: 1: Surgery, Gynecology, Obstetrics, and Pediatrics” by Eugen Strouhal, Bretislav Vachala , et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Medicine of the Ancient Egyptians: 2: Internal Medicine” by Eugen Strouhal, Bretislav Vachala, Hana Vymazalová Amazon.com;

“The Papyrus Ebers: Ancient Egyptian Medicine” by Cyril P. Bryan (Translator) 2021) Amazon.com;

“The Edwin Smith Papyrus: Updated Translation of the Trauma Treatise and Modern Medical Commentaries” by Gonzalo M. Sanchez and Edmund S. Meltzer (2012) Amazon.com;

“Pharmacy and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Proceedings of the Conference Held in Barcelona (2018) by Rosa Dinares Sola, Mikel Fernandez Georges, Maria Rosa Guasch Jane Amazon.com;

“Health and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Magic and Science” by Paula Alexandra Da Silva Veiga (2009) Amazon.com;

“Healthmaking in Ancient Egypt: The Social Determinants of Health at Deir El-Medina

by Anne E. Austin (2024) Amazon.com;

“Science and Secrets of Early Medicine: Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, China, Mexico, Peru”

By Jurgen Thorwald (1963) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Medicine” (Sciences of Antiquity) by Vivian Nutton (2012) Amazon.com;

“Illness and Health Care in the Ancient Near East: The Role of the Temple in Greece, Mesopotamia, and Israel” (Harvard Semitic Monographs) by Hector Avalos (1995)

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Tools and Cures Used by Ancient Egyptian Doctors

Surgical tools used by ancient Egyptian doctors included: knives, drills, saws, forceps or pincers, censers, hooks, bags tied with string, beaked vessels, vases with burning incense, Horus eyes, scales, pots with flowers of Upper and Lower Egypt, pots on pedestal, graduated cubits or papyrus, scrolls without side knot (or a case holding reed scalpels), shears, spoons. ~

The Temple of Sobek and Horus in Kom Ombo in Aswan contains sculpted wall reliefs with images of surgical instruments, bone saws and dental tools. The Cairo Museum has a collection of surgical instruments which include scalpels, scissors, copper needles, forceps, spoons, lancets, hooks, probes and pincers. [Source: Mark Millmore,discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Though Egyptian medical practices by no means could rival that of the present day physicians, Egyptian healers engaged in surgery, prescriptive, and many other healing practices still found today. Among the curatives used by the Egyptians were all types of plant (herbs and other plants), animal (all parts nearly) and mineral compounds. The use of these compounds led to an extensive compendium of curative recipes, some still available today. For example, yeast was recognized for its healing qualities and was applied to leg ulcers and swellings. Yeast's were also taken internally for digestive disorders and were an effective cure for ulcers.” [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

“The practices of Egyptian medical practitioners ranged from embalming to faith healing to surgery and autopsy. The use of autopsy came through the extensive embalming practices of the Egyptians, as it was not unlikely for an embalmer to examine the body for a cause of the illness which caused death. The use of surgery also evolved from a knowledge of the basic anatomy and embalming practices of the Egyptians. From such careful observations made by the early medical practitioners of Egypt, healing practices began to center upon both the religious rituals and the lives of the ancient Egyptians. +\

Medical Papyri from Ancient Egypt

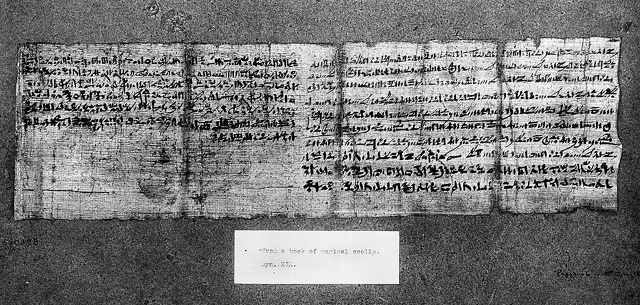

Edwin Smith papyrus

Joyce M Filer, an Egyptologist and expert on mummies and ancient Egyptian health issues, wrote for the BBC: “Ancient Egypt is justly famed for its literary output, and a certain class of texts-called magical-medical texts-gives us some indication of the doctors' treatments. As the name implies, the treatments involve elements of religious incantations, and medications concocted from a variety of substances so noxious as to drive away the demons that the Egyptians believed had brought the illness to the sufferer. [Source: Joyce M Filer, BBC, February, 17, 2011 |::|]

Anne Austin wrote: A physician would have most likely treated patients with remedies and incantations found in his medical papyrus. About a dozen extensive medical papyri have been identified from ancient Egypt, including one set from Deir el-Medina. These texts were a kind of reference book for the ancient Egyptian medical practitioner, listing individual treatments for a variety of ailments. The longest of these, Papyrus Ebers, covers anything from eye problems to digestive disorders. As an example, one treatment for intestinal worms requires the physician to cook the cores of dates and colocynth, a desert plant, together in sweet beer. He then sieved the warm liquid and gave it to the patient to drink for four days. [Source: Anne Austin, Assistant Teaching Professor, University of Missouri-St. Louis, The Conversation, May 3, 2021]

“Just like today, some of these ancient Egyptian medical treatments required expensive and rare ingredients that limited who could actually afford to be treated, but the most frequent ingredients found in these texts tended to be common household items like honey and grease. One text from Deir el-Medina indicates that the state rationed out common ingredients to a few men in the workforce so that they could be shared among the workers.

The Ebert papyrus runs for the equivalent of 110 pages and has 877 remedies. The papyrus is organized on treating particular parts of the body, but has sections on the head, toes, fingers and eyes. It also include remedies to parasitic stomach diseases and a small section on the heart. Among other things it say that a depressed skull fracture looks like a puncture in a pottery jar. ~

A text called the “Handbook of Ritual Power” — from the Coptic era but presumably based on some ancient Egyptian practices — tells readers how to cast love spells, exorcise evil spirits and treat “black jaundice,” a sometimes fatal bacterial infection that is still around today.

Edwin Smith Medical Papyri

One of the most informative documents on Egyptian medical practices is the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus. It was written around 1700 B.C. but most of the information is based on texts written around 2640 B.C., Imhotep’s time. The papyrus mainly describes wounds, and how to treat them, and has surprisingly little to say about diseases. It describes 48 surgical treatments for injures of the head, neck, shoulders, breast and chest and contains a list of instruments — including lint, swabs, bandage, adhesive plaster, surgical stitches and cauterization tools — used in treatments and surgeries, plus instructions on how to sutur a wound using a needle and thread It is also the earliest document to make a study of the brain.. [Source: Page of Egyptian Medicine, discoveringegypt.com]

Joyce M Filer wrote for the BBC: The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, named after its modern owner, “describes 48 cases of injury to the face, head, neck and upper spine. In each case a prognosis is given and, if this is favourable, suitable treatment is recommended. One case, number 11, describes the management of a broken nose, and the treatment, involving rolls of lint within the nostrils and external bandaging, can hardly be bettered even by modern doctors. As might be expected, no treatment is recommended for patients deemed fatally injured. The wise ancient Egyptian physician knew when a patient was beyond help. [Source: Joyce M Filer, BBC, February, 17, 2011 |::|]

At excerpt from the Edwin Smith papyrus on curing "Stupid Vision" reads: "Take the water (humor) contained in pigs eyes, take true antimony, red lead, natural honey, of each 1 Ro [about 15 cc]; pulverize it finely and combine it into one mass which should be injected into the ear of the patient and he will be cured immediately. Do and thou shalt see. Really excellent! Thou shalt recite as a spell: I have brought this which was applied to the seat of yonder and replaces the horrible suffering. Twice." ~

Medical Treatment in Ancient Egypt

ancient Egyptian medical tools

Joyce M Filer wrote for the BBC: “We have no direct information about treatment for diseases such as tuberculosis, polio or arthritis but no doubt, to judge from the variety of recipes in medical texts, any medication would involve fairly revolting ingredients. Dung from various animals, fat from cats, fly droppings and even cooked mice are just a small selection of the range of remedies the Egyptian doctor could recommend as treatment. [Source: Joyce M Filer, BBC, February, 17, 2011 |::|]

As a rule the Egyptian doctors thought they could see, without further examination, what was the matter with their patients. Many, however, were conscious that an exact knowledge of any disease is the foundation of a cure, and therefore in their writings,'' directed such straightforward diagnoses as for instance the following: “When thou findest a man who has a swelling in his neck, and who suffers in both his shoulder-blades, as well as in his head, and the backbone of his neck is stiff, and his neck is stiff, so that he is not able to look down upon his belly . . . then say: ' He has a swelling in his neck; direct him to rub in the ointment of antimony, so that he should immediately become well." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Or with one ill in his stomach: "If thou findest a man with constipation . . . with a pale face and beating heart, and dost find, on examining him, that he has a hot heart and a swollen body; that is an ulcer (?) which has arisen from the eating of hot substances. Order something that the heat may be cooled, and his bowels opened, namely, a drink of sweet beer to be poured over dry Neq'aut fruit; this is to be eaten or drunk four times. When that which comes from him looks like small black stones, then say: ' This inflammation departs. ' . . . If after thou hast done this thou examinest him and findest that that which he passes resembles beans, on which is dew . . . then say: ' That which was in his stomach has departed. " “Other obstructions in the abdomen gave rise to other symptoms, and required different treatment, thus when the doctor put his fingers on the abdomen and found it "go hither and thither like oil in a skin bottle," or in a case when the patient "vomits and feels very ill,"'' or when the body is "hot and swollen. "

If the illness were obstinate, the question arose which was to be employcd out of many various remedies, for by the beginning of the New Kingdom the number of prescriptions had increased to such an extent, that for some diseases there were frequently a dozen or more remedies, from amongst which the doctor could take his choice.

Ancient Egyptian Prosthetic Toe

Ancient Egyptian Prosthetic Toe

An artificial toe, dated to 950–710 B.C. and made of wood and leather, was discovered on a female mummy in 1997 in the tomb of Tabeketenmut in necropolis of Thebes, near Luxor. It is 12 centimeters (4.7 inches) from tip of toe to point of attachment and currently kept in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

According to Archaeology magazine: “Egyptians appear to have taken great pains to have the bodies of their dead buried intact. Some mummified remains are found with makeshift limbs and false eyes to replace missing parts. This artificial toe, attached to the right foot of a priest's daughter, is so well made, however, it's unlikely it was only intended to prepare her for the afterlife. [Source Archaeology magazine, May-June 2011]

“The dense hardwood used in the toe's construction is robust enough to withstand bodily forces — while walking, a big toe must bear up to 40 percent of a person's body weight. It also has a beveled edge at its attachment point, indicating it was deliberately designed to maximize comfort, says Jacqueline Finch, a visiting scientist at the University of Manchester's KNH Center for Biomedical Egyptology. She recruited two volunteers who are missing their right big toes to wear a reproduction of this device along with replica Egyptian sandals. Both reported that it was comfortable and assisted them in walking. Until now, an artificial leg made of bronze and wood and found buried with a Roman aristocrat in southern Italy dating to 300 B.C. was thought to be the first prosthesis. Finch's work suggests, however, that the Egyptians be credited with pioneering prosthetic medicine.

A reexamination of the prosthetic toe in the late 2010s revealed that it is even more sophisticated than originally thought. The artificial toe’s materials and design provided a surprising level of balance and movement, but the object’s creator also strove to make it as aesthetically pleasing and lifelike as possible. Tests have shown that the device was readjusted over time to suit its owner. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2017]

Child Mummy with a Dressed Wound

On December 30, 2021 scientists announced in a study published in the International Journal of Paleopathology, a peer-reviewed journal, that they uncovered the first example of a bandaged wound on a mummy — in this case the mummy of a young girl, aged four years or less, who died about 2,000 years ago. Whether this bandage was added as part of a religious ceremony or left after treatment is unclear. "It gives us clues about how they [ancient Egyptians] treated such infections or abscesses during their lifetime," Albert Zink, an author on the study, told Insider. The mummy was thought to be taken from the "Tomb of Aline" in the Faiyum Oasis, located southwest of Cairo, the study said. [Source: Marianne Guenot, Business Insider, January 14, 2022]

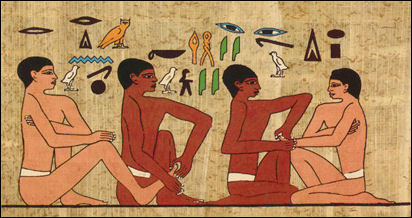

massage

Zink said the bandages were spotted while the scientists carried out routine CT scans of mummies, as can be seen in the scans below and annotated with the full-lined arrow. “The wound appeared to have been infected when she died, as the scans showed signs of "pus," Zink said. These signs of infection are marked by the dotted arrows in the scans below. "It's very likely that they applied some specific herbs or ointment to treat the inflammation of this area," which further analysis could identify, Zink said.

On the front of the mummy is a portrait of the child painted on linen fabric. Zink told Business Insider he wanted to get samples from the area to understand what caused the infection and how people at the time treated it. But that could entail unwrapping the mummy, which Zink said he was reluctant to do. Another option would be to collect a sample using a biopsy needle, he said.

According to Business Insider: “Zink says there was no clear explanation why, in this particular case, the bandages were left in place. "The question is whether it was just left in place and it remained despite the embalming process or whether they placed it," he said, referring to the embalmers. Wound dressings typically did not survive the mummification process. But it's possible the embalmers added the bandage on the body after the girl's death. Ancient Egyptians believed that the mummified body should be as perfect as possible for life after death, Zink said: "Maybe they tried somehow to continue the healing process for the afterlife. "

Ancient Egyptian Cancer Surgery

In a study published May 2024 in the Frontiers in Medicine journal, scientists said they had found evidence of the oldest known cancer surgery in pair of Egyptian skulls, both thousands of years old. The skulls had cut marks around cancerous growths. “We see that although ancient Egyptians were able to deal with complex cranial fractures, cancer was still a medical knowledge frontier,” one of the study's authors, Tatiana Tondini, said in a statement. [Source: Patrick Smith, NBC News, May 30, 2024]

A team led by Edgard Camarós, a paleopathologist at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain and the lead author of the study, looked at two skulls held by the University of Cambridge's Duckworth Collection, using micro-CT scanning and microscopic bone surface analysis, the study said. “We wanted to learn about the role of cancer in the past, how prevalent this disease was in antiquity, and how ancient societies interacted with this pathology,” said Tondini, a researcher at Germany’s University of Tübingen.

One of the skulls belonged to a male and was dated from 2,687 to 2,345 B.C., while the other was a female and dated from 663 to 343 B.C. The male skull had a large lesion surrounded by 30 or so small metastasized lesions around it. To their great surprise, researchers found cut marks around the lesions. “When we first observed the cut marks under the microscope, we could not believe what was in front of us,” Tondini said.

The female skull also had a large lesion consistent with a cancerous tumor that led to bone destruction, indicating the person might have been older. There are also two healed lesions from traumatic injuries, the study said. "It seems ancient Egyptians performed some kind of surgical intervention related to the presence of cancerous cells," said another co-author, professor Albert Isidro, a surgical oncologist at the University Hospital Sagrat Cor, in Barcelona, Spain.

Ancient Egyptian Medicines

Homer called the ancient Egyptians "a race of druggists." Hieroglyphics depicting senna leaves, a cathartic found in Egypt and one of the world's first known medicines, were found in the tomb of a court physician dating back to 4500 B.C. A variety of medicines were mentioned in the Petri Papyrus (1850 B.C.) and Ebers Papyrus (1550 B.C.). Many of the drugs named in these papyruses — rambling collections of hieroglyphic prescriptions and incantations — are still used today.

Ox liver — a good source of Vitamin A — was prescribed for night blindness. Patients with severe wounds were told to eat the mold from bread which later yielded penicillin. Castor plants were pressed into oil as a treatment for a variety of ailments. Pods from opium poppies were given to relieve pain. [Source: Lonnelle Aikman, National Geographic, September 1974]

Ox liver — a good source of Vitamin A — was prescribed for night blindness. Patients with severe wounds were told to eat the mold from bread which later yielded penicillin. Castor plants were pressed into oil as a treatment for a variety of ailments. Pods from opium poppies were given to relieve pain. [Source: Lonnelle Aikman, National Geographic, September 1974]

The earliest known laxatives used in Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, were made from ground senna pods and yellowish castor oil around 2500 B.C. Indigestion medicines were made from peppermint leaves and carbonates (antacids) and ethyl alcohol for pain relief.

The Egyptians used small doses of poisonous plants such as the deadly nightshade and thorn apple. A bas-relief shows Queen Nefertiti offering mandrake, a pain killer, to her ailing husband. The Egyptians also used onions to treat scurvy, aloe to relive upset stomachs and henbane as a sedative. Hard candies were used as cough drops. Other "recipes" seem a little impractical today. Parents, for example, were advised to give colicky babies "fly dirt that on the wall."

See Separate Article: MEDICINES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Magical Spells Used to Treat Illnesses

Rosalie David, professor at the University of Manchester, in the United Kingdom told CNN that the ancient Egyptians produced magical spells used to treat cancer-like illnesses, a few of which are described in papyri. One odd treatment for what may have been cancer of the uterus called for breaking up a stone in water, leaving it overnight, and then pouring it into the vagina. Another remedy described was fumigation: The patient would sit over something that was burning, David told CNN, adding that it’s still not certain that the maladies described were cancer.

In Ancient Egypt there were incantations that were to be spoken over various remedies in order to endow them with the right power. The following formula had to be recited at the preparation of all medicaments. “That Isis might make free, make free. That Isis might make Horus free from all evil that his brother Set had done to him when he slew his father Osiris. O Isis, great enchantress, free me, release me from all evil red things, from the fever of the god and the fever of the goddess, from death, and death from pain, and the pain which comes over mc; as thou hast freed, as thou hast released thy son Horus, whilst I enter into the fire and go forth from the water," etc. “Again, when the invalid took his medicine, an incantation had to be said which began thus: “Come remedy, come drive it out of my heart, out of these my limbs, strong in magic power with the remedy." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

A. Wiedemann wrote: "According to late accounts, the human body had been divided into thirty-six parts, each presided over by a certain demon, and it sufficed to invoke the demon of the part affected in order to bring about its cure—a view of matters fundamentally Egyptian. In the Book of the Dead we find that different divinities were responsible for the well-being of the bodies of the blessed; thus Nu had charge of the hair, Râ of the face, Hathor of the eyes, Apuat of the ears, Anubis of the lips, while Thoth was guardian of all parts of the body together. This doctrine was subsequently applied to the living body, with the difference that for the great gods named in the Book of the Dead there were substituted as gods of healing the presiding deities of the thirty-six decani, the thirty-six divisions of the Egyptian zodiac, as we learn from the names given to them by Celsus and preserved by Origen. In earlier times it was not so easy to be determined which god was to be invoked, for the selection depended not only on the part affected but also on the illness and symptoms and remedies to be used, etc. [Source: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, The Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“"Several Egyptian medical papyri which have come down to us contain formulas to be spoken against the demons of disease as well as prescriptions for the remedies to be used in specified cases of illness. In papyri of older date these conjurations are comparatively rare, but the further the art of medicine advanced, or rather, receded, the more numerous they became. It was not always enough to speak the formulas once; even their repeated recitation might not be successful, and in that case recourse must be had to other expedients: secret passes were made, various rites were performed, the formulas were written upon papyrus, which the sick person had to swallow, etc…. But amulets were in general found to be most efficacious, and the personal intervention of a god called up, if necessary, by prayers or sorcery. "

4,500-Year-Old Tomb of an Ancient Egyptian Doctor

Nikhil Swaminathan wrote in Archaeology magazine: A Czech team investigating the site of Abusir, a necropolis 15 miles south of Cairo, discovered the tomb of a royal physician dating back to the twenty-fourth century B.C. The doctor, Shepseskafankh, was a key member of the court of Niuserre, and his 2,500-square-foot limestone tomb contains a chapel and seven underground chambers, previously looted, where he and his family were interred. [Source: Nikhil Swaminathan, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2014]

“The most significant artifact found in the tomb was an 11.5-foot stela, or, as the archaeologists refer to it, a “false door,” on which were inscribed several titles that Shepseskafankh held. They included Priest of Re in the Temples of the Sun and Priest of Khnum. According to the excavation’s leader, Miroslav Bárta of the Czech Institute of Egyptology, Shepseskafankh was also known as “overseer of drugs of the Great House,” meaning he was the official doctor and pharmacist of the royal family.

“Bárta notes that Abusir likely contains dozens of large tombs erected for many high-ranking members of ancient Egypt’s 5th Dynasty. Officials of the 4th Dynasty are interred in Giza, whereas those of the 6th are at Saqqara. “The discovery of the tomb of Shepseskafankh,” says Bárta, “shows above all how rich the potential of the sites on the pyramid fields is. ”

Dentists in Ancient Egypt

The first known dentist was Hesi-Re, a physician who lived around 3000 B.C. and was known as "Chief of the Toothers and Chief of Toothers and the Physicians" and described as "the greatest physicians who treat the teeth.”

There was a lot of wear on mummy’s teeth. Some scholars believed that sand was used to get a fine grind for wheat and that their sieves were unable to remove all the sand. Thus the bread was gritty and this may explain the wear on mummy’s teeth. Many ancient people believed that pain was caused by creatures called toothworms.

Examinations of mummies and mummy remains have indicated that even pharaohs lost all their teeth. The most common form of treatment seemed to have been tooth extraction. Drilling through the jawbone may have been used to relieve abscessed teeth. Skulls from 2500 B.C. contained weak teeth that had been anchored to other teeth with gold wire.

Ancient Egyptian dentistry

The ancient Egyptians are credited with toothpaste. Mark Millmore of discoveringegypt.com wrote: “At the 2003 dental conference in Vienna, dentists sampled a replication of ancient Egyptian toothpaste. Its ingredients included powdered of ox hooves, ashes, burnt eggshells and pumice. Another toothpaste recipe and a how-to-brush guide was written on a papyrus from the fourth century AD describes how to mix precise amounts of rock salt, mint, dried iris flower and grains of pepper, to form a “powder for white and perfect teeth.”“ [Source:Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024