Home | Category: Education, Health and Transportation

INJURIES AND ACCIDENTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

fractured forearm with a splint

Fractures were common: many were to the upper arms and fibula (bone in the lower leg). Most healed were good realignments to the bone, indicating they had been set with a splint. Archaeologists also uncovered evidence of successful amputations and skull fractures in men and women mostly likely caused by an attack from a right-handed person.

Joyce M Filer wrote for the BBC: “Accidents, intentional violence and surgical intervention are all episodes of traumatic injury, and there is plenty of evidence for trauma from ancient Egyptian and Nubian sources. A fracture, which is a break in the structure of a bone, can occur in any bone in the skeleton, and the site of the fracture may give a clue as to how that injury was caused. Injuries to the head are particularly interesting as, whilst they may be accidentally caused, they are often the result of intentional violence. [Source: Joyce M Filer, BBC, February, 17, 2011 |::|]

“As in other ancient cultures, head injuries in Nile Valley populations tended to be sustained by more men than women, because men engaged in the manual work and military action that could lead to such injuries. For example, the bodies of about 60 male archers from the early Middle Kingdom period were found in a tomb at Deir el-Bahri, clearly showing head injuries caused by fighting: axe wounds, spear piercings and arrow lacerations. |::|

“Long bone injuries are frequently seen in ancient Egyptian bodies and are more likely to be the result of an accident. Injuries to the femur (upper leg bone) occurred quite commonly; whilst the relatively lower number of tibia (shin bone) fractures is thought to be caused by going barefoot, especially among agricultural workers. Fractures to the arms are interesting, as they may be the result of an accidental fall or, as has been suggested for some Nubian injuries, may be the result of using the arms defensively to ward off violent blows to the head.” |::|

RELATED ARTICLES:

HEALTH OF ANCIENT EGYPTIANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIFE EXPECTANCY OF ANCIENT EGYPTIANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN VIEWS ABOUT HEALTH africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DISEASE IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MALARIA, CANCER, PLAGUES factsanddetails.com ;

HEALTH CARE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DOCTORS AND MEDICAL TREATMENT IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MEDICINES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Oncology and Infectious Diseases in Ancient Egypt: the Ebers Papyrus? Treatise on Tumours 857-877 and the Cases Found in Ancient Egyptian Human Material” by Paula Veiga (2009) Amazon.com;

“Mummies, Disease and Ancient Cultures” by Thomas Aidan Cockburn, Eve Cockburn (1998) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Feast in Ancient Egypt” by Ellen Morris (2023) Amazon.com;

“Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies”

by Zahi Hawass and Sahar Saleem (2018) Amazon.com;

“Health and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Magic and Science” by Paula Alexandra Da Silva Veiga (2009) Amazon.com;

“Healthmaking in Ancient Egypt: The Social Determinants of Health at Deir El-Medina

by Anne E. Austin (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Medicine” by John F. Nunn (2002) Amazon.com;

“Medicine and Healing Practices in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David and Roger Forshaw (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Medicine of the Ancient Egyptians: 1: Surgery, Gynecology, Obstetrics, and Pediatrics” by Eugen Strouhal, Bretislav Vachala , et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Medicine of the Ancient Egyptians: 2: Internal Medicine” by Eugen Strouhal, Bretislav Vachala, Hana Vymazalová Amazon.com;

“An Ancient Egyptian Herbal” by Lise Manniche (2006) Amazon.com;

“Pharmacy and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Proceedings of the Conference Held in Barcelona (2018) by Rosa Dinares Sola, Mikel Fernandez Georges, Maria Rosa Guasch Jane Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Disease” by Charlotte Roberts, Keith Manchester Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Beni Hassan: Art and Daily Life in an Egyptian Province” by Naguib Kanawati and Alexandra Woods (2011) Amazon.com;

“24 Hours in Ancient Egypt: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Donald P. Ryan (2018) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

Health Issues Involving Children

Despite the fact that children played a central part in the lives of ancient Egyptians, pregnant women are seldom depicted. One of the few examples depicts queen Ahmose in the Deir el-Bahri divine birth sequence. In Sudan, a skeleton of an adult Nubian female was found with baby's skeleton lying across her ankles

Joyce M Filer wrote for the BBC: “Many women died as young adults, and childbirth and associated complications may well have been the cause.Although Egyptians 'experimented' with contraception-using a diverse range of substances such as crocodile dung, honey and oil-ideally they wanted large families. Children were needed to help with family affairs and to look after their parents in their old age. This would have led to women having numerous children, and for some women these successive pregnancies would have been fatal. Even after giving birth successfully, women could still die from complications such as puerperal fever. It was not until the 20th century that improved standards of hygiene during childbirth started to prevent such deaths. [Source: Joyce M Filer, BBC, February, 17, 2011 |::|]

“People are open to the greatest health risks during infancy and early childhood, and in Egypt and Nubia there was a high infant mortality rate. During the breastfeeding period the baby is protected from infections by ingesting mother's milk, but once weaned onto solid foods the chances of infection are high. Consequently many infants would have died of diarrhoea and similar disorders caused by food contaminated by bacteria or even intestinal parasites. In some ancient Egyptian and Nubian cemeteries at least a third of all burials are those of children, but such illnesses rarely leave telltale markers on the skeleton, so it is hard to know the exact numbers affected.” |::|

Mummies Appear to Show Many Ancient Egyptian Children Had Anemia

An examination of 21 ancient Egyptian mummified children revealed that one-third of them had the blood disorder of anemia, which is often connected with medical problems such as malnutrition and growth defects. In a study published April 13, 2023 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, an international team of researchers used full body CT (computed tomography) scans to examine the mummies of children who had died between the ages of 1 and 14 and determined they had anemia based on abnormal growth in the mummies' skulls and arm and leg bones. [Source: Hannah Kate Simon, Live Science, May 16, 2023]

Hannah Kate Simon wrote in Live Science: Seven of the mummies, or 33 percent of those studied, showed signs of anemia in the form of thickened skull bones, the researchers found. Today, anemia is thought to affect 40 percent of children under the age of 5 years old globally, according to the World Health Organization. This research on anemia in ancient Egypt "may shed light on ancient societies' health issues, dietary inadequacies, and social standards," Sahar Saleem, head and professor of radiology at Cairo University and a member of the Egyptian Mummy Project, told Live Science. Saleem was not involved in the study.

This study, possibly the first of its kind, included child mummies from various parts of Egypt dating as early as the Old Kingdom (third millennium B.C.) to the Roman Period (fourth century A.D.).Indigo Reeve, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland who was not involved in the study, defined anemia as "a lack of healthy red blood cells or hemoglobin." This condition can stem from a variety of causes, including dietary deficiencies, inherited disorders and infections, which can all lead to intestinal blood loss and poor absorption of nutrients, Reeve told Live Science. Anemia typically causes fatigue and weakness, but it can also cause irregular heartbeat and can be life-threatening depending on the type and severity, she added.

Childhood cases of anemia can cause the expansion of some bone marrow, which is found at the center of most bones, which can lead to odd and abnormal bone growth, such as the thickening of the cranial vault, the part of the skull that holds the brain, Reeve explained. Porous lesions can also appear on bones, especially on the skull, which can cause further medical problems.

The study uncovered some of these anemia-related issues in the mummified children. In one of the seven cases with thickened cranial vaults, a 1-year-old boy showed cranial signs of thalassemia, an inherited blood disorder that can cause mild to severe anemia due to reduced hemoglobin production; other symptoms of thalassemia can include inadequate and unusual bone growth and an increased risk of infections, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. The boy also had an enlarged tongue and a condition known as "rodent facies," which is an abnormal growth of the cheekbones and an elongated skull. This boy's severe anemia, compounded with other difficulties, likely caused his death, the researchers theorized.

It's unclear how these ancient children came to have anemias, but the disorder can be caused by malnutrition, iron deficiency in pregnant mothers, chronic gastrointestinal issues and bacterial, viral or parasitic infections, all of which are thought to have been prevalent in ancient Egypt, the researchers said.However, the study's small sample of 21 child mummies is not representative of an entire population or time period, the researchers noted. Further, the CT scans "produced blurry images due to low resolution that prevented interpretation" of additional signs of anemia, Saleem said.

Ancient Woman in Nubia with Holes on Her Bones

In a study published in March 2024 in the International Journal of Paleopathology, archaeologists from the University of Chicago said they discovered a woman in a tomb at a site called Sheikh Mohamed, near Aswan, dated to 1750 to 1550 B.C. who had holes in the bones of her joints, suggesting she suffered from a rare autoimmune disease. [Source Irene Wright, Miami Herald, February 9, 2024]

Irene Wright wrote in the Miami Herald: More than two dozens tombs made up the Nubian Pan-Grave cemetery, the researchers said, a type of cemetery common among the Medjay nomadic people that lived in the eastern deserts of Egypt more than 3,000 years ago. When they reached Tomb 5 and saw nearly 60 percent of the skeleton inside had been preserved, according to the study. The bones belonged to a woman between the ages of 25 and 30, the researchers said, and with so much of her skeleton intact, they looked closer at the small bones in her hands and her feet. They were riddled with lesions, pock marks and holes. The diagnosis? She had rheumatoid arthritis. “I’m used to seeing osteoarthritis — it’s one of the most common joint conditions that we see archaeologically,” study author Mindy Pitre told Live Science. “It looks like bone on bone where you get this smooth look that resembles ivory. In rheumatoid, you don’t get that whatsoever. The minute I recognized it, I noticed that the lesions didn’t look typical.”

Rheumatoid arthritis only impacts between 0.5 and 1 percent of adults between the ages of 30 and 50 globally today, the study authors said, making it a rare disease in the modern era. In ancient records, it’s even more rare. “This case of (rheumatoid arthritis) is important because few archaeological examples exist,” the researchers said. “At least 1000 complete skeletons need to be examined to find one clear case of RhA.” Rheumatoid arthritis, or RhA, is a chronic autoimmune disease that can be caused by genetics or environmental factors and attacks the body’s joints, according to the National Institutes of Health. The condition would have made the ancient woman’s life very difficult, the researchers said. “Based on their bony presentation, this individual’s joints (particularly the hands and feet) may have felt achy, stiff and tender and would have been prone to swelling, all of which may have had an impact on hand function and ability to carry out daily activities,” the researchers wrote. “Their pain would have increased over time, and they would have been more at risk for chronic conditions such as heart disease.”

Study Finds Clogged Arteries in a Third of Ancient Mummies

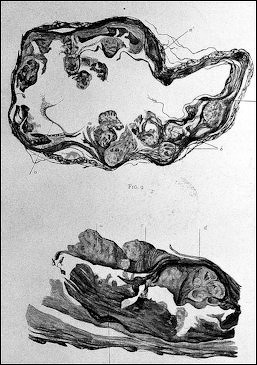

arterial lession from Egyptian mummies

According to a study published online in 2013 in the journal Lancet, CT scans of 137 mummies showed evidence of atherosclerosis, or hardened arteries, in one-third of those examined. Atherosclerosis causes heart attacks and strokes."Heart disease has been stalking mankind for over 4,000 years all over the globe," said Dr. Randall Thompson, a cardiologist at Saint Luke's Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City and the paper's lead author. [Source: AP March 11, 2013 |||]

According to Associated Press: “More than half of the mummies were from Egypt, while the rest were from Peru, southwest America and the Aleutian islands in Alaska. The mummies were from about 3800 B.C. to 1900 A.D. The mummies with clogged arteries were older at the time of their death, around 43 versus 32 for those without the condition. In most cases, scientists couldn't say whether the heart disease killed them. |||

“Other experts warned against reading too much into the mummy data. Dr. Mike Knapton, associate medical director at the British Heart Foundation, said calcified arteries could also be caused by other ailments including endocrine disorders and that it was impossible to tell from the CT scans if the types of calcium deposits in the mummies were the kind that would have sparked a heart attack or stroke. "It's a fascinating study but I'm not sure we can say atherosclerosis is an inevitable part of aging," he said, citing the numerous studies that have showed strong links between lifestyle factors and heart disease.” |||

Artery Disease in Ancient Egypt

CT scans of some Egyptian mummies carried out by a team of cardiologists at the Egyptian National Museum of Antiquities in Cairo revealed signs of atherosclerosis — a buildup of cholesterol, inflammation and scar tissue in the walls of the arteries, a problem that can lead to heart attack and stroke — according to research published in The Journal of the American Medical Association. Natasha Singer, New York Times, November 23, 2009]

Natasha Singer wrote in the New York Times, “The cardiologists were able to identify the disease in some mummies because atherosclerotic tissue often develops calcification, which is visible as bright spots on a CT image. The finding that some mummies had hardened arteries raises questions about the common wisdom that factors in modern life, including stress, high-fat diets, smoking and sedentary routines, play an essential role in the development of cardiovascular disease, the researchers said.

“It tells us that we have to look beyond lifestyles and diet for the cause and progression of this disease,” Dr. Randall C. Thompson, a cardiologist at St. Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City, Mo. Told the New York Times. He was part of the team of cardiovascular imaging specialists who traveled to Cairo last year. “To a certain extent, getting the disease is part of the human condition,” he said.

In February 2009, the team of cardiologists — one Egyptian and four American — conducted whole-body scans of 20 of the museum’s mummies that were well preserved and thus likely to have identifiable arteries. The study also included two mummies that had been scanned by other researchers. Sixteen of the people mummified had been members of a pharaoh’s court, among them two priests, a king’s minister and his wife, and a nursemaid to a queen. They lived between 1981 B.C. and A.D. 334, the cardiologists said.

Among the 16 mummies that had identifiable cardiovascular tissue, there were 5 confirmed and 4 probable cases of atherosclerosis. The researchers found calcification in the leg arteries and the aorta of some mummies, which means that these ancient Egyptians had risk factors for problems like strokes and heart attacks — though not necessarily that they had developed heart disease before they died. As with modern humans, arterial calcification was more prevalent among the mummies who lived longer. The study’s small sample and the subjects — high socioeconomic status may mean the findings do not extend to more ordinary ancient Egyptians, said Dr. Adel H. Allam, the Egyptian cardiologist on the team. “They were rich people, and the habit of diet and physical activity could be a little bit different than other Egyptians who lived at that time,” said Dr. Allam, an assistant professor of cardiology at the Al Azhar Medical School in Cairo.

The group hit upon the idea of examining mummies for arterial disease in 2007, when another cardiologist, Dr. Gregory S. Thomas, was visiting Dr. Allam in Cairo and happened upon a mummified pharaoh named Menephtah in the museum. A plaque by Menephtah’s case explained that the pharaoh, who died about 1200 B.C., had been afflicted with atherosclerosis. Dr. Thomas, a clinical professor of medicine and cardiology at the medical school of the University of California, Irvine, did not believe it. “For one thing, how would they know?” Dr. Thomas said in a phone interview last week from Cairo. “For another thing, what would people be doing with atherosclerosis 3,000 years ago, without tobacco, with an all-natural diet and, presumably, with much more walking?”

The oldest mummy in whom the group found hardened arteries was Lady Rai, a nursemaid to a famous queen, who died in about 1530 B.C. when she was between 30 and 40 years old. Dr. Thompson told the New York Times the calcification in her aorta looked similar to that in images of his own patients with atherosclerosis in Kansas City.

Posture of Scribes So Bad It Disfigured Their Skeletons

Ancient Egyptian scribes worked in hunched over positions that were so extreme, appears to have caused them to develop osteoarthritis in their joints and other skeletal issues — a finding based on an analysis of 69 adult male skeletons — 30 of whom were scribes — who were buried between 2700 and 2180 B.C. in a necropolis in Abusir published June 27, 2024 in the journal Scientific Reports. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, June 28, 2024]

Scribes often performed repetitive administrative tasks that involved sitting in certain positions for prolonged periods of time, according to a statement. Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science: Researchers noticed that the scribes' skeletons showed more obvious degenerative changes in their joints, compared to the adult males who held other occupations. The areas most affected included the right collarbone, the right upper arm bone where it connects with the shoulder socket, the bottom of the right thigh bone where it meets the knee and the vertebra at the top of the spine.

The researchers also noticed unique indentations in both kneecaps of each scribe, and a "flattened surface on a bone in the lower part of the right ankle," according to the statement. The cause of these skeletal changes was likely due to scribes sitting for long periods in a cross-legged position or while kneeling on their left legs with their right legs bent upwards with the papyrus in their laps. And — much like today's office workers — the scribes hunched over as they wrote.

"In a typical scribe's working position, the head had to be bent forward and the spine flexed, which changed the center of gravity of the head and put stress on the spine," lead author Petra Brukner Havelková, an anthropologist in the Department of Anthropology at the National Museum in Prague, told Live Science. "And the correlation between [jaw disorders] and cervical spine dysfunction or neck/shoulder symptoms is well documented or supported by clinical studies. " She added, "We may realize that although they were high-ranking dignitaries who belonged to the ancient Egyptian elite, they suffered the same worries as we do today and were exposed to similar occupational risk factors in their profession as most civil servants today. "

There have also been numerous statues and wall art found in tombs showing scribes sitting in these exact positions performing their tasks. "The relief decoration in tombs and scribal statues give us an idea of the postures of the scribes of the time," Dulíková said. "They were in different sitting and standing positions. These are therefore very important for studying the physical changes involved. " The scribes' jaws and first bones in their right thumbs also appeared to be affected, bearing wear-and-tear not seen in the other skeletons. This was likely the result of the scribes chewing the ends of rush stems to create writing debensils, which they then pinched with their thumbs as they wrote. "Our research reveals that remaining in a cross-legged sitting or kneeling position for extended periods, and the repetitive tasks related to writing and the adjusting of the rush pens during scribal activity, caused the extreme overloading of the jaw, neck and shoulder regions," the authors wrote in the study. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024