Home | Category: Education, Health and Transportation

HEALTH IN ANCIENT EGYPT

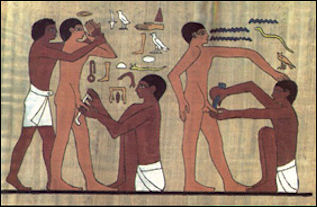

Circumcision Commoners, who lived in Ain Ladkha, 130 mile southwest of Luxor, between 100 B.C. to A.D. 200, died on average at the age of 38. In the cemeteries of the pyramid builders, most men died between 40 and 45 most women died between 30 and 35. Few people lived beyond 50. More women below 30 died than men of a similar age. This and the figure above is probably explained by complications due to childbirth. Upper class women lived five to ten years longer than lower class ones. Still few people lived beyond 40.

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: The prescription for a healthy life, (which was almost always given by a member of the priestly caste) meant that an individual undertook the stringent and regular purification rituals (which included much bathing, and often times shaving one's head and body hair), and maintained their dietary restrictions against raw fish and other animals considered unclean to eat. Also, and in addition to a purified lifestyle, it was not uncommon for the Egyptians to undergo dream analysis to find a cure or cause for illness, as well as to ask for a priest to aid them with magic. This obviously portrays that religious magical rites and purificatory rites were intertwined in the healing process as well as in creating a proper lifestyle. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

Excavations in graveyards dated to 3500 B.C. have revealed the bodies of individual who generally seemed healthy and well nourished but died around 15 to 35 years of age. Graveyards are often filled with children and young mothers, which implies that infant mortality and the death rate among young mothers was very high.

Vanessa Thorpe wrote in The Observer, “Mummies disinterred down the ages are usually found to belong to those who were between 25 or 30 years old when they died, and these would have been the bodies of the elite, people who lived in comparative wealth. A few ancient Egyptians survived until they reached 70 or 80 and they were then revered because the gods had so favoured them.” "110 was seen as the ideal target age, but I can't imagine anyone ever made it," [Source: Vanessa Thorpe, The Observer, October 24, 2010]

RELATED ARTICLES:

LIFE EXPECTANCY OF ANCIENT EGYPTIANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN VIEWS ABOUT HEALTH africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DISEASE IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MALARIA, CANCER, PLAGUES factsanddetails.com ;

HEALTH PROBLEMS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: INJURIES, ANEMIA, CLOGGED ARTERIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

HEALTH CARE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DOCTORS AND MEDICAL TREATMENT IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MEDICINES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

Dr. Arthur Aufderheide of the University of Minnesota is regarded as one of the world’s leading experts on the dissection of mummies and a founder of modern paleopathology — the study of ancient diseases.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Health and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Magic and Science” by Paula Alexandra Da Silva Veiga (2009) Amazon.com;

“Healthmaking in Ancient Egypt: The Social Determinants of Health at Deir El-Medina

by Anne E. Austin (2024) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Food and Drink” by Hilary Wilson (2008) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Medicine” by John F. Nunn (2002) Amazon.com;

“Medicine and Healing Practices in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David and Roger Forshaw (2023) Amazon.com;

“Oncology and Infectious Diseases in Ancient Egypt: the Ebers Papyrus? Treatise on Tumours 857-877 and the Cases Found in Ancient Egyptian Human Material” by Paula Veiga (2009) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Feast in Ancient Egypt” by Ellen Morris (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Medicine of the Ancient Egyptians: 1: Surgery, Gynecology, Obstetrics, and Pediatrics” by Eugen Strouhal, Bretislav Vachala , et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Medicine of the Ancient Egyptians: 2: Internal Medicine” by Eugen Strouhal, Bretislav Vachala, Hana Vymazalová Amazon.com;

“An Ancient Egyptian Herbal” by Lise Manniche (2006) Amazon.com;

“Pharmacy and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Proceedings of the Conference Held in Barcelona (2018) by Rosa Dinares Sola, Mikel Fernandez Georges, Maria Rosa Guasch Jane Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Disease” by Charlotte Roberts, Keith Manchester Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Tough Life for Ancient Egyptians

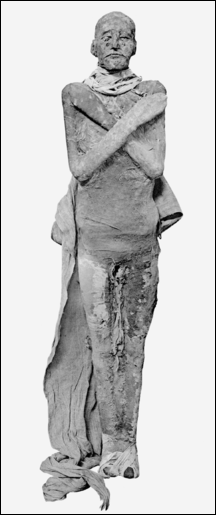

Ramses III mummy A study by team of researchers lead by Gerome Rose and Barry Kemp of the University of Arkansas of people buried in the cemetery of Tell el-Amarna — a city that was the capital of ancient Egypt for 15 years in the 14th century B.C. under the Pharaoh Akhenaten — found that life was short, brutish and tough for the ancient Egyptians. Many suffered from anemia, fractured bones, stunted growth and high juvenile mortality rates. The study found that anemia ran at 74 percent among children and teenagers buried there and 44 percent among adults. Several teenagers had severe spinal injures, thought to have been caused by construction accidents that occurred during the building of the city. The average height was 159 centimeters among men and 153 centimeters among women. Rose said, “Short stature reflect a diet deficient in protein...People are not growing to their full potential.” [Source: Alaa Shahine Reuters, March 29, 2008]

Rose, a professor of anthropology at the University of Arkansas, told Reuters adults buried in the cemetery were probably brought there from other parts of Egypt."This means that we have a period of deprivation in Egypt prior to the Amarna phase," he said. "So maybe things were not so good for the average Egyptian and maybe Akhenaten said we have to change to make things better," he said.

"A very large number of ordinary cemeteries have been excavated but just for the objects and very little attention has been paid for the human remain," Kemp told Reuters. “The idea of treating the human remains ... to study the overall health of the population is relatively new." Paintings in the tombs of the nobles show an abundance of offerings, but the remains of ordinary people tell a different story.

Rose displayed pictures showing spinal injuries among teenagers, probably because of accidents during construction work to build the city. The study showed that anemia ran at 74 percent among children and teenagers, and at 44 percent among adults, Rose said. The average height of men was 159 cm (5 feet 2 inches) and 153 cm among women. "Adult heights are used as a proxy for overall standard of living," he said. "Short statures reflect a diet deficient in protein. ... People were not growing to their full potential."

Egyptian Environment and Health

Giving birth

Joyce M Filer, an Egyptologist and expert on mummies and ancient Egyptian health issues, wrote for the BBC: “Many accounts of ancient Egypt begin by stressing the influence of the environment, and particularly the great River Nile, on the everyday life of its people. It is a good place to start in considering the health of the Egyptians, as the Nile was the life-and health-giving source of water for drinking, cooking and washing. It also, however, harboured parasites and other creatures that were less beneficial. [Source :Joyce M Filer, BBC, February, 17, 2011 |::|]

“As people waded through standing water, particularly in the agricultural irrigation channels, parasites such as the Schistosoma worm could enter the human host, via the feet or legs, to lay eggs in the bloodstream. These worms caused a lot of damage as they travelled through various internal organs, making sufferers weak and susceptible to other diseases. Sometimes ancient Egyptians took in guinea worms in their drinking water. The female guinea worm would travel to its preferred site-the host's legs-in order to lay her eggs, again causing ill health. |::|

“Despite the fairly wide range of foodstuffs, cereals, fruits, vegetables, milk and meat produced by the ancient Egyptians, not everybody would have had adequate nutrition. There is evidence from the bodies of ancient Egyptians, retrieved from their graves, that some people suffered nutritional deficiencies. |::|

“As in other societies, ancient Egyptians also suffered from more everyday types of sickness. Records reveal that some tomb builders complained of headaches, others were too drunk to go to work, and some had emotional worries. Although it is difficult to gain information from mummies and skeletons about eye complaints, some artwork suggests that such problems were not uncommon. Flies, dirt and sand particles would have caused infections in the eyes and lungs. Many Egyptians wore eye paint, which may have been an attempt to ward off eye infections-it is now known that the green eye paint containing malachite had medicinal properties.” |::|

Short Lifespans and Early Deaths in Ancient Egypt

Joyce M Filer wrote for the BBC: “Life expectancy in ancient Egypt and Nubia was lower than in many modern populations. Whilst some ancient Egyptians undoubtedly enjoyed longevity, most were unlikely to live beyond about 40 years of age. This may seem young by today's standards, but it is important to view age within the context of a particular society. Thus, today people are shocked at the death of King Tutankhamun at the age of about 18 years, yet in his own society he was already 'mature' in terms of family and kingly responsibility. [Source: Joyce M Filer, BBC, February, 17, 2011 |::|]

“Many women died as young adults, and childbirth and associated complications may well have been the cause. Although Egyptians 'experimented' with contraception-using a diverse range of substances such as crocodile dung, honey and oil-ideally they wanted large families. Children were needed to help with family affairs and to look after their parents in their old age. This would have led to women having numerous children, and for some women these successive pregnancies would have been fatal. Even after giving birth successfully, women could still die from complications such as puerperal fever. It was not until the 20th century that improved standards of hygiene during childbirth started to prevent such deaths. |::|

“People are open to the greatest health risks during infancy and early childhood, and in Egypt and Nubia there was a high infant mortality rate. During the breastfeeding period the baby is protected from infections by ingesting mother's milk, but once weaned onto solid foods the chances of infection are high. Consequently many infants would have died of diarrhoea and similar disorders caused by food contaminated by bacteria or even intestinal parasites. In some ancient Egyptian and Nubian cemeteries at least a third of all burials are those of children, but such illnesses rarely leave telltale markers on the skeleton, so it is hard to know the exact numbers affected.” |::|

Health of Ancient Egyptians as Seen Through Their Bones

arms and legs

A CT scan of the skull of a 2,200-year-old Egyptian mummy displayed at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem showed signs of osteoporosis and tooth decay. Other remains from ancient Egypt include a child's skull with anaemic lesions in the eye sockets and an adult with an abscess drainage hole in his worn teeth. [Source: BBC]

Joyce M Filer wrote for the BBC: “Some conditions do leave evidence of their existence on bones. Anaemia, often a consequence of iron deficiency during childhood, leaves markers on the roofs of the eye sockets or on the top of skulls in the form of small holes, and these are frequently seen on Egyptian skulls. [Source: Joyce M Filer, BBC, February, 17, 2011 |::|]

“In ancient Egypt, iron deficiency could have been caused by infestation of bloodsucking parasites, such as hookworms, or by people living on a largely cereal diet, with relatively little iron content. Even the wealthier classes, who had access to meat, may not have consumed it on a regular basis. An examination of the great king Ramesses II, however, revealed he suffered from hardening of the arteries-and this was possibly as a consequence of rich living. Whilst anaemia was not a direct cause of death, it would have made sufferers weak and vulnerable to other diseases. |::| Arthritis and dental problems are features of many ancient societies, and ancient Egypt was no exception. Although arthritis can set in after an accident or infection, generally it is a consequence of the ageing process. As joints wear down through usage the cartilage wears away, leaving the bones rubbing together and causing the ends of the bones to develop lipping at the edges-leaving proof of the sufferer's condition for posterity. |::|

Worn teeth and cavities testify to the poor dental health of some Egyptians. The quantity of sand particles in their bread has been suggested as the cause of the often serious amount of wear on ancient Egyptian teeth. Many Egyptian dentitions present a round drainage hole, suggesting the presence of an abscess, where infection has forced an exit through the bone. This may have solved the problem, but there may also have been many deaths caused by un-drained dental abscesses in ancient times. |::|

“Evidence for serious conditions such as tuberculosis, leprosy, tumours, polio, cleft palate has also been noted in exhumed Egyptian and Nubian bodies.” |::|

How Age and Sex are Estimated from Skeletal Remains

Sonia Zakrzewski of Southampton University wrote: “In order to undertake demographic analyses, reliable and precise estimates of age and sex are required. Biological ages (as opposed to chronological or social ages) are estimated from markers of maturation and growth or markers of degeneration of the bones and teeth. Similarly, while it may seem odd to refer to the “estimation” of sex, the sex of skeletons (as opposed to mummies) can be treated as “known” only under certain circumstances, such as if sexing through genetic methods or the visual inspection of preserved external genitalia. [Source: Sonia Zakrzewski, Southampton University, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2015, escholarship.org ]

“ Assigning sex and age categories to skeletal material involves errors and probabilities, and so this process should be considered as estimation or assessment rather than the determination of age and sex. Although sex is of less importance than aging when considering the ancient Egyptian life span, it does have an impact on demographic studies. In an ideal situation, some individuals would form a reference sample of persons of “known” sex against which other individuals might be sexed. Ideally this would be done through genetic studies, but more commonly and practically involves using the Phenice pubic bone characteristics.

arthritis bone deformities

“Research is currently ongoing to develop metric methods for estimating sex for ancient Egyptians based on modern forensic methods. Biological age can more accurately be assessed for juveniles than for mature aged individuals. Long bone length, dental development, and timing of formation of ossification centers (zones in which bones form in juveniles as part of the growth process) and epiphyseal union (joining together of such separate bones as part of the growth and development process) can all be used to estimate age-at-death for subadult remains. Dental development is considered the most accurate means of estimating age-at-death in subadults because it is thought to be under the greatest genetic control. By adulthood, no further dental or bone growth occurs, and hence age estimation of adults relies on degenerative methods.

“The most common methods include assessment of the pubic symphysis (anterior area of the pelvis), auricular surface (where each of the two pelvic bones joins the sacrum at the base of the spine), rib ends, cranial sutures, and dental wear. Some of these, such as dental wear, are problematic for Egyptian samples as many ancient Egyptian teeth exhibit high grades of dental wear as a result of the foods consumed and the storage and processing methods used for those foods. Transition analysis and multifactorial methods, based upon Bayesian analysis, appear hopeful in improving the accuracy and precision of Egyptian age estimates. These latter methods use “known” reference samples and survivorship models to estimate at what age those known aged individuals transition from one skeletal phase to another. In the absence of Bayesian methods, most bioarchae-ologists working in Egypt rely on multiple indicators to obtain the best estimates of age. Skeletal and Mummified Assemblages As noted earlier, there are issues with the overall representatives of assemblages of Egyptian skeletal and mummified material. Within western museum collections, skeletons have usually been obtained and curated as a result of historical personal connections between excavators, patrons, and/or museum curators.”

Health Data on Ancient Egyptians from Skeleton Collections

skeletol remains in basketwork coffin, 3000 BC

Some interesting findings have come from individual skeletons and mummies but it is hard make generalizations from these about the general ancient Egyptian population. Sonia Zakrzewski of Southampton University wrote: “Many large Egyptian skeletal collections exist, such as the Phoebe Hearst Museum of Anthropology (UC Berkeley), the Duckworth Collection (Cambridge University), the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (Washington DC), the Natural History Museum (London), the Peabody Museum (Harvard University), the Naturhistorisches Museum (Vienna), and the Kasr el Aini medical school (Cairo) collections, but none can be said to be truly representative of either a site, a period, or even a complete cemetery. Large collections of mummies are rarer, but do exist in locations such as the Egyptian Museum. More commonly, individual mummies or a few mummies are found in a variety of different museums, often brought to the west as a result of family travels or business transactions in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. [Source: Sonia Zakrzewski, Southampton University, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2015, escholarship.org ]

“Such collections are therefore not random and are rarely suitable for demographic studies. Following the pioneering work of the Manchester Mummy Project, and its development of the International Ancient Egyptian Mummy Tissue Databank, “virtual” collections are being developed, so that biological data may be available to multiple researchers. The osteological paradox influences our understanding of ancient Egyptian demography and longevity. Wood et al. showed that the absence of skeletal evidence of disease does not mean that there was an absence of disease; individuals may have died at either an early or acute phase of the disease, which would mean that those people died before their body developed lesions as a result of the disease. Furthermore, the implication of the osteological paradox is that individuals who exhibit skeletal markers of chronic disease may actually reflect long-term survival with such chronic conditions, and therefore may be the healthier individuals within the overall population. Furthermore many diseases affect only the soft tissues and so do not leave osseous signatures. This means that aspects of health are very hard to ascertain from the skeletal and palaeopathological record.

“Individuals who survived repeated episodes of stress and infection may have many skeletal markers of such episodes of ill-health or stress upon their bodies. This is likely to impact unevenly on the sample, as individuals who lived longer have had more time to become exposed to, and develop markers of, such stresses and diseases. This does not mean that older-aged individuals within a group were less healthy than younger individuals, but rather may imply that the frailer individuals died when they were young, but before they developed skeletal lesions.“

What Mummies Tell Us About Ancient Egyptian Health

Ramses IV mummy Mummy expert Dr. Arthur Aufderheide estimates that only 10 percent to 15 percent of mummies show the cause of death. They are more revealing about chronic ailments, the presence of parasites and determining what people ate (if their intestines are still there).

In 1910, Marc Armand Ruffer, a French microbiologist, found dried eggs of the schistosomiasis worm in kidneys of two 3000-year-old mummies. Schistosomiasis remains a disease that is prevalent in Egypt today. In other mummies he found gallstones, inflamed intestines, and a spleen that had apparently been enlarged by malaria. Ruffer looked inside ancient blood vessels and found calcified spots — evidence of hardening of the arteries, surprising considering the ancient Egyptians ate a low-fat high-fiber diet with a lot of grains. Ruffer invented a solution of salts for rehydrating ancient tissues (some researchers today use fabric softener) and popularized the term “paleopathology.”

Over the decades scientists have learned to glean information from ancient bones. Leprosy, anemia, stunted growth, syphilis and tuberculosis leave behind characteristic marks in the eye sockets, spine and other bones. Bones also leave behind clues about arthritis and vitamin deficiencies and can indicate whether a person who died violently such as being struck by an ax or knife or a blunt instrument. Even so 80 percent of ailments — plague, aneurisms, measles and others — leave behind no clues or marks.

A 2,200 year old mummy displayed at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem in 2016 showed how unhealthy some ancient Egyptians were. Scott Simon of NPR wrote: “His name was Iret-hor-irou, the protective Eye of Horus. He was an Egyptian priest, 5 foot 6, who was probably between 30 and 40 years of age when he died, according to tests run on the linen in which he's been wrapped since the second century B.C. The priest seems to have suffered from a series of ailments, which we think of as afflicting people who may have a little too much idle time on their hands-osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease and lack of vitamins from the sun. [Source: Scott Simon, NPR.org, July 30, 2016]

“Osteoporosis is a disease that's characteristic of the 20th century when people don't work so hard. Galit Bennett, who curated the mummy exhibit, told the Associated Press, we are glued to screens. We were very surprised that there were people who didn't do physical work and that it affected their bodies like this man here. The mummy also reportedly has tooth decay.”

King Tutankhamun's Health Determined from CT Scans and DNA Tests

X-ray of Tutankhamun's head

King Tutankhamun was five feet six inched tall and slightly built and 18 to 20 when he died. In the June 2005 issue of National Geographic, artists and scientists produced striking images of what they believed King Tutankhamun looked like using a CT (computerized tomography) scans and facial reconstruction. The images that were produced showed a fair-skinned young man with a ski-sloped nose, a small cleft planate, an elongated skull, good teeth, and a slight overbite possessed by other members of his family. He had no cavities in his teeth. [Source: A.R. Williams, National Geographic, June 2005]

Tutankhamun age was determined by the maturity of his skeleton (his skull had not closed) and his wisdom teeth (which hadn’t grown in yet). Careful examinations of his head revealed he had a distinctive egg-shaped head, and he lacked the feminine appearance he seems to have in his death mask and other artifacts. He may have fractured his thighbone.

CT images, which were part of a study published in the February 2010 of the Journal of the American Medical Association, revealed that Tutankhamun had a club foot and other deformities, meaning he probably had to walk with a cane. DNA analysis of Tutankhamun and his relatives seem to indicate that he had several disorders, some of which ran in his family such as a bone disease and club foot. The authors of the study wrote Tutankhamun was “a young but frail king who needed canes to walk because of the bone-necrotic and sometimes painful Koehler disease II, plus oligodactyly (hypophalangism) in the right foot and clubfoot on the left.”

Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic,” When we began the new study, Ashraf Selim and his colleagues discovered something previously unnoticed in the CT images of the mummy: Tutankhamun's left foot was clubbed, one toe was missing a bone, and the bones in part of the foot were destroyed by necrosis — literally, "tissue death." Both the clubbed foot and the bone disease would have impeded his ability to walk. Scholars had already noted that 130 partial or whole walking sticks had been found in Tutankhamun's tomb, some of which show clear signs of use.” [Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, September 2010]

“Some have argued that such staffs were common symbols of power and that the damage to Tutankhamun's foot may have occurred during the mummification process. But our analysis showed that new bone growth had occurred in response to the necrosis, proving the condition was present during his lifetime. And of all the pharaohs, only Tutankhamun is shown seated while performing activities such as shooting an arrow from a bow or using a throw stick. This was not a king who held a staff just as a symbol of power. This was a young man who needed a cane to walk.” [Ibid]

Famine in Ancient Egypt

Laurent Coulon of the University of Lyon wrote: “In ancient Egypt, food crises were most often occasioned by bad harvests following low or destructive inundations. Food crises developed into famines when administrative officials— state or local—were unable to organize storage and redistribution systems. Food deprivation, aggravated by hunger-related diseases, led to increased mortality, migrations, and social collapse. In texts and representations, the famine motif is used as an expression of chaos, emphasizing the political and theological role of the king (or nomarch or god) as “dispenser of food.” [Source: Laurent Coulon, University of Lyon, France,UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

Relief showing starving nomads from Unas' causeway

“In pre-modern times, food production in Egypt was heavily dependent on cultivation of the Nile Valley lands, watered and fertilized by the annual flood. Because the inundation level was irregular, food crises recurred fairly frequently, ranging from food shortages to famine, a term which, strictly speaking, should be reserved for “critical shortage of essential foodstuffs, leading through hunger to a substantially increased mortality rate in a community or region, and involving a collapse of the social, political and moral order”. The correspondence between Hekanakht, a landowner who lived during the early 12th Dynasty, and his dependents gives an account of the serious difficulties encountered by various strata of society at a time when the Nile only partially flooded the cultivated lands. Epigraphic and literary sources give numerous mentions of successive years of low flood, exemplified by the biblical episode in which Joseph interprets Pharaoh’s dream of seven lean cows and seven dried stalks of wheat. At the beginning of the First Intermediate Period, Ankhtify’s autobiography recounts a dark period when, except in his nome, “all of Upper Egypt was dying of hunger and people were eating their children.” Paleopathologic studies also provide cases of nutritional stress and high mortality at various times, but it is only for the Greco-Roman Period that we possess the papyrological documentation for a historical overview of famines in ancient Egypt; the study of such documentation shows—not surprisingly—the coincidence of famines with plague epidemics.

“Famines were also capable of prompting migrations of population. Ankhtifi’s autobiography mentions that “the whole country has become like locusts going upstream and downstream.” Migrations probably played a significant role in the birth of Egyptian civilization during the Holocene Period, when drastic climatic changes and increasing aridity may have forced inhabitants of the Western and Eastern Deserts to settle on the banks of the Nile.

“The consequences of low or destructive inundations depended to a large degree on the ability of administrative officials—state or local—to anticipate subsistence crises: sufficient storage of surpluses from one year to the next and an efficient redistribution system could counter bad harvests. Conversely, famine clearly correlates with mismanagement of the state administration—for example, during the 20thDynasty, when the workmen of Deir el- Medina were compelled to go on strike to obtain their salaries. The prosperity of the Egyptian state was nevertheless famous throughout the Near East, and New Kingdom pharaohs used grain supplies as diplomatic gifts when their allies, especially the Hittites, were facing starvation; on the other hand, the Egyptian army commonly induced famine artificially, through destruction of harvests and cattle, to subdue foreign enemies.

“The Egyptians viewed food deprivation as a liminal experience, approaching chaos. Because the experience of chaos was included as a kind of “rite of passage” in the funerary ritual, the deceased were therefore required to suffer hunger and thirst before being regenerated by funerary offerings. The evocation of the elite suffering famine is also an essential feature of the social anarchy described in texts such as The Prophecy of Neferty and The Admonitions of Ipuwer. Conversely, representations occasionally emphasize the opulence of the Egyptians from the Nile Valley by contrasting them with the starving nomadic tribes, as we see, for example, in 5th-Dynasty reliefs depicting emaciated Bedouin and in the 12th-Dynasty relief of a cowherd in a tomb of Meir. “Nourishing the land” and “giving bread to the hungry” are the basic definitions of the role of the king and high officials; the evocation of famine in hieroglyphic texts is embedded in this ideological discourse. Recent studies suggest that the repeated evocation of famines in First Intermediate Period texts reflects the employment of a new rhetoric of the nomarch as “dispenser of food,” featuring realistic descriptions rather than the standard clichés . To use these texts as evidence of climatic changes is therefore misleading, the more so as this self-presentation of the nomarch is still attested during the Middle Kingdom. Divine intervention against famine is also a frequent motif of Late Period texts, among the most famous of which is the so-called “Famine Stela” at Sehel, a Ptolemaic inscription celebrating the prosperity granted to the region by the god Khnum after a seven-year famine during the reign of Djoser.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024