Home | Category: Government, Military and Justice

SYMBOLS OF THE EGYPTIAN PHARAOH

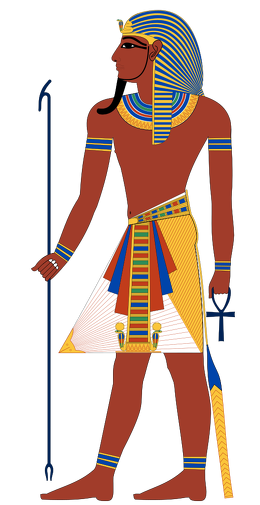

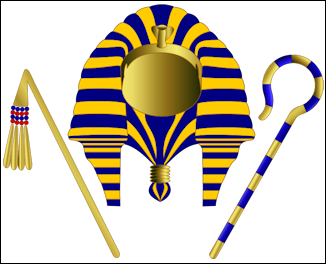

crook and flail, Pharaoh symbols As a sign of their authority a pharaoh wore a false beard, a lion’s main and a “nemes” or headcloth with a sacred cobra. When offering were made he waived the royal “sekhem” (scepter) over them. The beard on the statue of a pharaoh identifies him as being one with Osiris, god of the dead. The cobra and vulture on his forehead symbolize the Upper and Lower kingdoms of Egypt. When the king sat on his throne wearing all of his symbols of office—the crowns, scepters, and other ceremonial items—it was believed the spirit of the great god Horus spoke through him.

The crook and flail held the Pharaoh’s hands symbolized the king's power and authority and also linked him with Osiris (statues of Osiris also have a crook and flail). The crook was a short stick curved at the top, much like a shepherd’s crook. The flail was a long handle with three strings of beads. The pharaoh's power was also symbolized by a flabellum (fan) held in one hand.

The sickleshaped sword {Khopesh), named after its shape, also seems to have been a symbol of royalty. The regalia of the Pharaohs seems to belong to a time which the Egyptian wore nothing but a loincloth, and when it was considered a special distinction that the king should complete this loincloth with a piece of skin or matting in front, and should adorn it behind with a lion's tail.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Pharaohs: The Rulers of Ancient Egypt for Over 3000 Years” by Dr Phyllis G Jestice (2023) Amazon.com;

“Pharaoh: Art and Power in Ancient Egypt” by Marie Vandenbeusch (2024) Amazon.com;

“Kingship, Power, and Legitimacy in Ancient Egypt: From the Old Kingdom to the Middle Kingdom” by Lisa K. Sabbahy (2004) Amazon.com;

”The Names of the Kings of Egypt: The Serekhs and Cartouches of Egypt's Pharaohs, along with Selected Queens” by Kevin L. Johnson PhD and Bill Petty PhD (2012) Amazon.com;

“Pharaoh's Boat” by David Weitzman Amazon.com;

“Symbol & Magic in Egyptian Art” by Richard H. Wilkinson (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt: An Illustrated Dictionary” by Manfred Lurker | (1984) Amazon.com;

“Myth and Symbol in Ancient Egypt” by Robert Thomas Rundle Clark Amazon.com;

“Esoterism and Symbol” by R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz (1985) Amazon.com;

“The Pharaohs” by Joyce Tyldesley (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt: A Genealogical Sourcebook of the Pharaohs” Amazon.com;

Clothes of the Pharaoh

A lion's tail with the ends rounded off that hung down from the skirt of the Pharaoh was one of the most ancient symbols of royalty. Another indication of high rank were strips of white material which great lords of the Old Kingdom often wound round the breast or body when they put on their gala dress; or allowed to hang down from the shoulders," when in their usual dress they went for a walk in the country; or when they went hunting. A broad band of this kind was no protection against the cold or the wind, it was rather a token by which the lord might be recognized. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

During the Old Kingdom the royal ornaments were very simple. It is easy to see that the usual form of the royal dress originated in prehistoric times, when the only garment was a loincloth round the loins, with two or three ties hanging down in front, it was considered a luxury that the ruler should replace these ties by a piece of matting or fur, and, as further decoration, should add the tail of a lion behind. In very old rock steles a king is seen standing clothed in this way, killing his enemies — Bedouins. This is only an ancient symbolical representation, and we must not imagine that the king really wore this costume of a chief.

In the time of the 5th dynasty the loincloth had long become the dress of the lower orders, all the upper classes in Egypt were wearing a short skirt. The king wore this skirt sometimes over, but more usually under his old official costume. Both corners of the piece of stuff were then rounded off, so that the front piece belonging to the loincloth could be seen below. Sometimes the whole outfit was made of pleated golden material — and must have been quite a fine costume. The king appeared at times in the costume of a god; he then either bound his royal loincloth round the narrow womanish garment in which the people imagined their divinities to be dressed, .or he wore one of the strange divine diadems constructed of horns and feathers, and carried the divine scepter.

The royal clothes were very complex even in the time of the Old Kingdom; in later times they were essentially the same, though more splendid in appearance. In the later period special importance was attached to the front piece of the royal skirt, which was covered with rich embroidery, uraeus snakes were represented wreathing themselves at the sides, and white ribbons appeared to fasten it to the belt. If, according to ancient custom, the Pharaoh wore nothing but this skirt, it was worn standing out in front in a peak, which was adorned with gold ornamentation. Usually, however, the kings of the New Kingdom preferred to dress like their subjects, and on festive occasions, they put on the long transparent under dress as well as the full over dress, the short skirt being then worn either over or under these robes. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Well-preserved clothes found in King Tut tomb include lose-fitting, sleeveless tunics worn over loin clothes, linen belts, jeweled sandals made of reed, white loin cloths and head scarves. Some of the fabrics were plain white and others were embroidered with red, yellow and blue threads and studded with gold. Scientists were able confirm the boy-kings age from a small, delicate, linen cloth.

Keepers of the Royal Clothes

Keepers of the Royal Clothes were employed by the Pharaoh. There were many of these officials During the Old Kingdom, and they seem to have held a high position at court. These officials were called the “superintendent of the clothes of the king," the “chief bleacher," the “washer of Pharaoh," and the “chief washer of the palace." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Even the sandals had their special custodian,' and for the wigs there were the “wig-maker of Pharaoh," the “upper and under wigmakers of the king,"' and the “superintendent of the wig-makers. " It was the duty of those officials, who had the care of the monarch's hair, to take charge of the other numerous headdresses of the king; they were called “keepers of the diadem," '' and boasted that they “adorned the brow of thclr god," or of “the Horus."

There was a special superintendent and clerk, the chief. He offers incense before metalworkcr and chief artist for the care of the royal " jewels “— which at the same time formed part of the charge of the treasury; the superintendence of the clothes of the king was also vested in the same department. There were not so many of these officials in later times, yet during the Middle Kingdom, “the keeper of the diadem who adorns the king “had a high position at court. He had the title of “privy councillor of the two crowns," or “privy councillor of the royal jewels, and maker of the two magic kingdoms. "

Crowns and Headdresses of the Egyptian Pharaoh

The Pharaoh shaved off both hair and beard liked many of his subjects, and like them he replaced them by artificial ones. The artificial beard fastened under his chin was longer than that usually worn in the Old Kingdom. The king also covered his head with a headdress of which fell over his shoulders in two pleated lappets; it was twisted together behind, and hung down like a short pigtail. The uraeus (representation of a sacred serpent), the symbol of royalty, is always found on his head-dress. This brightly-colored poisonous snake seems to rear itself up on the brow of the king, threatening all his enemies, as formerly it had threatened all the enemies of the god Ra. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Crowns and headdresses were mostly made of organic materials and have not survived but we know what they looked like from many pictures and statues. The best known crown is from Tutankhamun’s golden death mask. The White Crown represented Upper Egypt, and the Red Crown, Lower Egypt (around the Nile Delta). Sometimes these crowns were worn together and called the Double Crown, and were the symbol of a united Egypt.

On festive occasions the king would wear his crown, either the white crown of Upper Egypt, a curious high conical cap, or the scarcely less quaint red crown of Lower Egypt with its high narrow back, and the wire ornament bent obliquely forward in front. Sometimes he wore both crowns — the double crown — the white one inside the red, and the wire stretching forward from the former. There was also a third crown worn by the kings of the New Kingdom, called the Blue Crown or war helmet. This was called the Nemes crown and was made of striped cloth. It was tied around the head, covered the neck and shoulders, and was knotted into a tail at the back. The brow was decorated with the “uraeus,” a cobra and vulture.

The crowns for the most part remained unchanged in all periods. Later the diadems of the gods with their horns and feathers came more into fashion than in the earlier periods. It was also the custom that Pharaoh, even in times of peace, should wear his war-helmet (khepresh).

Divine power was ascribed to the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt, which are referred to as the magic kingdoms, and during the Middle Kingdom a regular priesthood, instituted by the keepers of the diadem, was appointed to these two crowns. The office of keeper of the diadem seems to have been suppressed under the New Kingdom, or it may have been replaced by the “overseer of the ointments of the king's treasury, superintendent of the royal fillet of the good god. " '

Thrones in Ancient Egypt

The throne of the Pharaoh was part of his royal regalia and was where he gave audience. It at least sometimes included a canopy raised on pretty wooden pillars, a thick carpet on the floor, a seat and footstool of the usual shape. It was brilliantly colored and decorated like the great seat of Horns, according to the numerous representations from the time of the New Kingdom. When we examine the decoration, we see that it befits a royal throne: Africans and Asiatics appear to carry the seat, and a royal sphinx, the destroyer of all enemies, is represented on either arm at the side. On the floor, and therefore under the feet of the monarch, are the names of the enemies he has conquered, and above, on the roof, are two rows of uraeus snakes, the symbol of royal rank. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Klaus P. Kuhlmann of the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo wrote: “By today’s definition, a “throne” is the seat of a king or sovereign. In ancient Egypt, a plethora of terms referred to the throne, but none apparently carried this specific connotation. Explicit reference to the seat of a king or god was made by addressing the latter’s “elevated” position. There were two major types of thrones: a basic (“sacred”) one of the gods and of pharaoh as their heir and successor that had the shape of a square box (block-throne) and a “secular” one that incorporated a pair of lions into a stool or chair (lion-throne) and depicted pharaoh as powerful ruler of the world. Thrones usually stood on a dais inside a kiosk, elevating the ruler well above his subjects and displaying his supreme social rank. At the same time, the arrangement was meant to evoke a comparison with the sun god resting on the primordial hill at the moment of creating the world. The enthronization of pharaoh was thought to be a perpetuation of this cosmogonic act, which was referred to as “the first time”. As an object, which could be desecrated (for example, by usurpation), the Egyptian throne underwent purification rites. There is no evidence, however, of it ever having received cultic reverence or having been deified (as the goddess Isis). [Source: Klaus P. Kuhlmann, German Archaeological Institute, Cairo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“For most people in Africa and the ancient Near East—worldwide, in fact—“squatting” was and is the common position of repose, as it was also for the ancient Egyptians. Amongst ordinary Egyptians, mats (tmA) remained the most commonly used piece of “furniture” for sitting or lying down. Pharaoh on his throne, therefore, ruled over “the mats,” i.e., his “lowly” subjects . There is evidence, however, that this basic household item originally conferred “status” to its owner, a fact in tune with modern ethnographic data from Africa. Gods are said to be “elevated” on their mats, or the justified dead will be granted the privilege of sitting on “the mat of Osiris”. Archaizing tendencies during the late stages of Egyptian history resulted in the use of the reed mat (= pj wpj, “split,” i.e., reeds) as a word for “throne.”

Although forcing a posture, which “squatting” people generally experience as being less relaxing, stools and chairs were eagerly adopted by Egypt’s nobility because the raised position signaled “superiority” rather than being a means of achieving more comfort. Ancient Egyptians even attempted to “squat” on a chair. Like a crown or scepter, the chief’s chair became one of ancient Egypt’s most important royal insignia as the quintessential symbol of divine kingship.

“The manufacture of thrones involved precious materials like ebony and gold or electrum/fine gold. The frequent expression xndw bjAj (or: xndw n bjA, “throne made of iron,” e.g., PT 1992c) might more generally refer to the use of “mining products” (i.e., metal and precious stones for inlay work) rather than the use of “iron” as the manufacturing material of the throne. Offices connected to the throne were much less common than previously assumed. Assured are jrjw st pr aA, “guardians of the palace throne,” xntj xndw, “he before the throne,” TAj jsbt n nb tAwj, “carrier of the throne of the Lord of the Two Lands,” and maybe Xrj tp st nsw, “servant of the royal throne/chamber”.

Ancient Egyptian Thrones As Symbols of the King’s Divine Power

Ramses II

Klaus P. Kuhlmann of the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo wrote: “Gods acknowledged pharaoh as their “son” and legitimate heir by bequeathing to him their thrones as the one piece of ancestral symbols of office explicitly referred to. It was mainly Ra, Atum, Amun, Geb, and Horus who confirmed pharaoh’s rightful claim to power by saying “to thee I give my throne…”. This preeminent status amongst Egypt’s regalia derived from the dogma of pharaoh’s rule being first and foremost cosmogonic in nature. The king’s enthronization upon a dais was intended to recall and reenact the “first time” (zp tpj), i.e., the establishment of cosmic order and equilibrium (maat) when the sun god descended upon the primeval hill and created the world in its proper god-given state. This is why the throne could also be referred to as “she (i.e., st, nst) who keeps alive maat”. It has also been suggested that the throne might have had a deeper meaning representing the sky and that it was a symbol of perpetual rebirth. [Source: Klaus P. Kuhlmann, German Archaeological Institute, Cairo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Usurpation of the throne resulted in its desecration and the need for ritual purification. No convincing evidence exists, however, that it ever became the object of cultic reverence or deification. Religious texts are free of any allusion to such a fact. PT 1153b - 1154b—a key reference in connection with any such suggestion—refer to the throne (-kiosk) as having been “made by the gods, made by Horus, created by Thoth” and not by “the Great Isis” on whose lap the newborn-kings were pictured, sitting as if on a throne.

“None of the many Egyptian terms referring to the “throne” imply the “regal” or “religious” connotation the word carries today. Being “special” as the seat of a god or king was expressed by referring to the throne as being “elevated,” i.e., standing raised above its surroundings. st, nst, jsbt, mnbjt, and bHdw are derived from lexical roots denoting “to sit” or “to rest”. Other expressions originally referred to physical aspects like shape—for example, xndw: from a curved bar; hdmw, “box,” for the block-throne — or position as in the case of the frequent term st wrrt and tpj rdww indicating the throne’s elevated position in the kiosk (or in the holy of holies) on a dais, which was also referred to as a “high rising and tall” mnbjt.

“Words for the royal “palanquin” are mostly self-explanatory: wTzt Tzj/wTz, qAyt qA ; for Hmr and zpA(t), cf. Semitic Hml, “carry,” and Semitic zbl, “basket,” respectively. Other words like bkr(t) (Coptic belke), bdj, ndm, and skA resist etymological explanation. Words semantically related to “throne” often show graphically “simple” determinatives like , (a litter with an ancient type of curved shrine), or (steps, dais) indicating that the object was a “place of rest” and could be carried or stood raised. The block-throne sign on the head of Isis (Ast: hse) is not a symbol but “writing” (= s/se). It allowed the identification of iconographically undifferentiated female deities just as other hieroglyphic signs like or on the head of other goddesses denoted a “reading” as “Nephthys” or “Nut,” respectively.”

Types of Ancient Egyptians Thrones

Klaus P. Kuhlmann of the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo wrote: “Basically, Egyptian thrones came in two shapes, which seem to have coexisted since early Old Kingdom times. A square block incorporating a short backrest represented a simple “traditional” type (earliest example under Khufu). It remains unclear whether this type of seat evolved from (a flight of three brick-made) stairs as early sign shapes seem to suggest or from a bundle of reeds. In general, the block-throne has a Hwt-like design ) on its sides. This is the typical throne of gods, who “preside” over a temple (Hwt-nTr), and it is mainly—but not exclusively—in a religious context that also pharaoh is shown on such a (“sacred”) block-throne. The other type is the lion-throne that combines a chair with a tall backrest with figures of two lions flanking it. Famous examples are the thrones of the Khafra statues from the king’s valley temple at Giza or Tutankhamen’s throne. No armrests are shown in examples of three-dimensional thrones from the Old Kingdom although they are part of the throne of queen Neith. Egyptian beds flanked by lions, cheetahs, or hippopotami offer several formal analogies to the lion-throne, but the concept is a common one and much older than Egyptian civilization. The earliest example—showing a seated female figure between two felids — comes from Çatal Höyük in Anatolia and dates to Neolithic times. [Source: Klaus P. Kuhlmann, German Archaeological Institute, Cairo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“The lion-throne was the characteristic (“secular”) royal throne of ancient Egypt. Armchair-type lion-thrones are frequently depicted from the New Kingdom on. By this time, the pairs of lion legs present in three-dimensional examples of the Old Kingdom had been reduced to four legs, and the backrest had been turned into the stylized shape of an elegantly (though unnaturally) erect tail. Stool-type lion-thrones (without armrests only seldom show the animal’s head). Textual evidence indicates that prior to the lion-throne gaining general acceptance, also stools with bull’s legs (frequently found in tombs of Egypt’s Proto- and Early Dynastic elite) had served as thrones. Lightweight stools and folding chairs were also embellished with symbols of royalty (lion legs, zmA) and accompanied the king into the field or during more pleasurable outings be turned into a rigid throne with a backrest. Possible explanations might be the aspect of royal “leisure” associated with such stool- types or, on the contrary, the symbolism derived from being used by a “warrior”-king. There is no apparent reason, however, to identify its function as “ecclesiastical”, comparable to medieval faldistoria (armless folding chairs).

“When it became necessary to carry the king in procession, either type of throne was simply put on a portable support. During inaugurations and jubilees, the support often took the shape of a basket, which gave the allusion that the king was “presiding” over the festival HAb) or was “the Lord of Sed Festivals” (nb HAb-sd). Prior to the Amarna Period, officials were received at court before the “elevated throne” (st wrrt), pharaoh “shining” (Haj) above them like the sun god on the primeval hill and embodying the last link to Egypt’s erstwhile king-gods. Akhenaten broke with this traditional throne kiosk imagery. Even the term st wrrt was exchanged for jsbt aAt (probably meaning the same: “elevated throne”), and during official functions, the royal pair appeared seated on a simple stool. Instead, the “window of appearance”—a dais with surrounding parapet and a front reminiscent of a broken-lintel doorway— became the essential feature of interaction between the king and his subordinates. Inspired, no doubt, by the country’s age-old concept of portable shrines (e.g., divine barges) and justice being spoken at the “gate”, Akhenaten adapted the “window” also for venturing before the public, adding it to the royal palanquin together with pairs of lions and sphinxes as symbols of royal and apotropaic power. Presumably, the contraption was meant to convey the message that the king was “approachable,” i.e., willing to grant audience and justice to the common people, too. This understanding is corroborated by the fact that during public oracular processions, also deities—for example, the deified Amenhotep I or Amun in his so-called “aniconic form”—were called upon while being carried about in similar palanquins with a broken-lintel facade. Reliefs and drawings depict just the parapet in side view, but three-dimensional examples also show the broken-lintel door in the front. This type of throne—at least of the aniconic form of Amun—seems to have been called bHdw.

Tutankhamun's throne

“The throne is shown to rest at least on a mat. Usually it stands raised on a - shaped (double) dais (surmounted by curvy canopies: ) or inside (often very elaborate) kiosks consisting of four columns supporting a canopy made of a framework of lintels surmounted by a cavetto cornice. The earliest example dates to the Middle Kingdom. Since Amenhotep III, more elaborate kiosks are in evidence packing two, even three kiosks into one another. The columns are usually of the lotus-capital type with or without buds tied to the shaft. So- called “lily”-capitals may replace the lotus or the “lily” occurs in combination with the lotus. Botanically the flower does not actually represent a type of lily, and it seems likely that this is a monumentalized version of the Upper Egyptian heraldic plant (a flowering type of “sedge”?), which has not yet been identified beyond question. Three-stage composite capitals of papyrus flowers (and buds) were also used and became more frequent from the Amarna Period on. A consistent feature on the kiosk since the New Kingdom are the winged solar disc and bunches of grapes on the lintel.

Symbols and Ornamentation on the Ancient Egyptian Throne

King Tutankhamun’s wooden throne is covered in sheets of gold, silver, gems and glass and is decorated with an intimate scene of the queen rubbing Tutankhamun with perfumed oil beneath a floral pavilion. The rays of the sun god Aten shine on the couple, giving them the sign for life, the Ankh. The throne is made from wood, which is partly gold plated and inlaid with minute pieces of ivory, ebony, semi-precious stones and coloured glass. The high curved back is fitted to a stool with crossed legs carved to represent the necks and heads of ducks. The deeply curved seat (designed to hold a cushion) is inlaid with ebony and ivory in imitation of a spotted animal skin. [Source: Robert Partridge, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Klaus P. Kuhlmann of the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo wrote: “The vegetal features and the image of the solar god above it match the dais’ symbolic interpretation as the “primeval hill,” i.e., the fertile land appearing in the receding waters of the inundation. Sprouting with vegetation, Egypt provided the king with all kinds of vital produce and allowed him to lead a merry, carefree life. Representing two highly important vegetal commodities, lotus and papyrus epitomized Egypt’s most archetypal plants of the primordial world. Because of their symbolic and practical value in everyday life, they figured ubiquitously in art and architecture. In the time of Amenhotep III, vegetal capitals were also embellished by protomes of ducks, omnipresent in the pools and puddles left by the receding inundation. For Egyptians, the duck represented “fowl” as a basic type of nourishment and offering Apd, “bird”). Providing a counterbalance to the (Lower Egyptian) papyrus appears to have been the (Upper Egyptian) “lily”-capital’s sole raison d’être, which also explains its comparatively modest deployment in architectural designs since the time of king Djoser. Throughout the ancient world, wine was considered a drink of gods and royalty symbolizing a ruler’s happy and content life. It appears that the kiosk originated from primitive lightweight shades erected for trellising vines and for having a pleasurable time in a garden. [Source: Klaus P. Kuhlmann, German Archaeological Institute, Cairo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Ornamental patterns—many of them hieroglyphic signs—decorating the throne and its paraphernalia relate symbolically to the dogma of divine kingship, to the power of rule, or functioned as apotropaica. A variation of the block-throne (Hwt) hieroglyph is the (srx) on the sides of the block-throne, the earliest examples dating to the time of Amenhotep III. Rarely, the srx was also combined with a lion stool. The srx-decoration was probably inspired by the Horus-name of the royal titulary and alludes to the king as “living Horus” and “Lord of the royal palace”. The fact that pharaoh’s rule was “based” on the gifts of eternal “life” (anx, ), “endurance” (Dd, ), and“wellbeing” (wAs, ) bestowed upon him by the gods is expressed by representing these signs along the dais.

cartouche of Thutmosis III

Cathie Spieser, an independent researcher in Switzerland, wrote: “The cartouche is an elongated form of the Egyptian shen-hieroglyph that encloses and protects a royal name or, in specific contexts, the name of a divinity. A king’s throne name and “Amongst hieroglyphic symbols of authority and dominance, one finds the -sign (zmA, “unite”) in combination with papyrus and “sedge” symbolizing the “Two Lands” (i.e., Upper and Lower Egypt) united under one ruler. Hence the expression zmA(y)t, “unifier,” for the throne, which is said to “unite” (jab) the living under pharaoh. Gods of the country’s two parts, who are handling or tying the two heraldic plants of Upper- and Lower Egypt to the zmA, may augment the sign, as well as figures of northern and southern foreigners on lion- thrones. Foreigners—or their hieroglyphic symbol, the bow —are also represented on footstools or the dais. The theme of pharaoh triumphing over the rest of the world is also taken up on the armrest of thrones by depicting the royal sphinx trampling upon Egypt’s enemies. Graphic variations of the -hieroglyph on the dais (and footstool) illustrate pharaoh’s rule over the “civilized” Egyptian world, praising their leader. Differently colored stripes with a pattern reminiscent of feathers are also a frequent decorative design displayed on the sides of Hwt block-thrones.

“Essentially, lions and sphinxes flanking the king’s throne or before and on the dais seem to have been images of the king himself evoking a leader’s fierce strength and supremacy. This is suggested by the analogous griffin—furtive ruler of Egypt’s deserts—that also symbolizes aggressive, overwhelming power, as well as by the exchange of the lion protomes for human heads on the queen’s throne. Animals—because of their natural or imagined powers—took on the role of warding off evil and protecting the person of the ruler. Lion heads decorated the abaci of the throne kiosk, alternating with heads of the demon-god Bes, who is sometimes likened to the lion. Bucrania were mounted on the canopy supplementing the three dangerous lion aspects of the king by yet another one associated with deadly animal force dnD, “rage”). Kiosk lintels were also decorated with Hathoric-heads, recalling images of the king standing protected under the head of the Hathor-cow. Freezes of uraei crowning the canopy or snakes (Wadjet), vultures (Nekhbet), and falcons (Horus) protecting the king on arm- and backrests of the throne are all part of the comprehensive theme of divine animal powers watching over the king. “

Cartouches

birth name were each enclosed in a cartouche, forming a kind of heraldic motif expressing the ruler’s dual nature as both human and divine. The cartouche could occur as a simple decorative component. When shown independently the cartouche took on an iconic significance and replaced the king’s, or more rarely, the queen’s, anthropomorphic image, enabling him or her to be venerated as a divine entity. Conversely, the enclosure of a god’s or goddess’s name in a cartouche served to render the deity more accessible to the human sphere. [Source: Cathie Spieser, independent researcher, Switzerland, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The cartouche derives from the Egyptian shen-ring, a hieroglyphic sign depicting a coil of rope tied at one end, meaning “ring, circle,” the root Sn (shen) expressing the idea of encircling. Symbolically, the cartouche represents the encircling of the created world by the sun disc—that is, the containment of “all that the sun encircles.” Originally, the shen-ring was probably an amulet formed from a length of papyrus rope looped into a circle with an additional binding. The cartouche is an elongated shen-ring, extended to accommodate and magically protect a royal name.

“The convention of enclosing the king’s name in a cartouche initially appeared on royal monuments and may possibly date back as early as the First Dynasty, although there is currently little conclusive evidence to support this supposition. Recent work on early writing may well shed light on the question. The cartouche was first used to enclose the king’s birth (given) name. The earliest attested example of an enclosed birth name— that of Third Dynasty pharaoh Huni, found on a block at Elephantine—is doubtful. Well attested, however, are examples on royal monuments of Sneferu (Fourth Dynasty) and his successors. By the middle of the Fifth Dynasty, during the regency of Neferirkara, the newly instituted throne name is also enclosed within a cartouche.

See Separate Article: CARTOUCHE: MEANING, PURPOSE, VENERATION africame.factsanddetails.com

Royal Names in Ancient Egypt

The royal names and titles always appeared to the Egyptians as a matter of the highest importance. The first title consisted of the name borne by the king as a prince. This was the only one used by the people or in history; it was too sacred to be written as an ordinary word, and was therefore enclosed in an oval ring in order to separate it from other secular words. Before it stood the title “King of Upper Egypt and King of Lower Egypt. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The unification of Upper Egypt (southern Egypt) and the Lower Egypt (northern Egypt) was of great importance in the history of Egypt. The official title of the Pharaoh was always the “King of Upper Egypt and the King of Lower Egypt. " It was the same with the titles of his servants; originally they were the superintendents of the two houses of silver, or of the two storehouses, for each kingdom had its own granary and its own treasury.

During the Old Kingdom the idea arose that it was not suitable that the king, who on ascending the throne became a demigod, should retain the same common name he had borne as a prince. As many ordinary people were called Pepi, it did not befit the good god to bear this vulgar name; therefore at his accession a new name was given him for official use, which naturally had some pious signification. Pepi became "the beloved of Ra"; 'Esse, when king, was called, "the image of Ra stands firm"; and Mentuhotep is called “Ra, the lord of the two countries. " We see that all these official names contain the name of Ra the Sun-god, the symbol of royalty. Nevertheless, the king did not give up the family name he had borne as prince, for though not used for official purposes, it yet played an important part in the king's titles.

See Separate Article: ROYAL NAMES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Amarna Palace, the Amarna Project

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024