Home | Category: Religion and Gods / Government, Military and Justice / Language and Hieroglyphics

CARTOUCHE

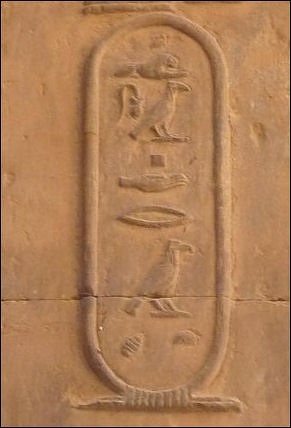

cartouche at Kom Ombo

Cathie Spieser, an independent researcher in Switzerland, wrote: “The cartouche is an elongated form of the Egyptian shen-hieroglyph that encloses and protects a royal name or, in specific contexts, the name of a divinity. A king’s throne name and birth name were each enclosed in a cartouche, forming a kind of heraldic motif expressing the ruler’s dual nature as both human and divine. The cartouche could occur as a simple decorative component. When shown independently the cartouche took on an iconic significance and replaced the king’s, or more rarely, the queen’s, anthropomorphic image, enabling him or her to be venerated as a divine entity. Conversely, the enclosure of a god’s or goddess’s name in a cartouche served to render the deity more accessible to the human sphere. [Source: Cathie Spieser, independent researcher, Switzerland, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The cartouche derives from the Egyptian shen-ring, a hieroglyphic sign depicting a coil of rope tied at one end, meaning “ring, circle,” the root Sn (shen) expressing the idea of encircling. Symbolically, the cartouche represents the encircling of the created world by the sun disc—that is, the containment of “all that the sun encircles.” Originally, the shen-ring was probably an amulet formed from a length of papyrus rope looped into a circle with an additional binding. The cartouche is an elongated shen-ring, extended to accommodate and magically protect a royal name.

“The convention of enclosing the king’s name in a cartouche initially appeared on royal monuments and may possibly date back as early as the First Dynasty, although there is currently little conclusive evidence to support this supposition. Recent work on early writing may well shed light on the question. The cartouche was first used to enclose the king’s birth (given) name. The earliest attested example of an enclosed birth name— that of Third Dynasty pharaoh Huni, found on a block at Elephantine—is doubtful. Well attested, however, are examples on royal monuments of Sneferu (Fourth Dynasty) and his successors. By the middle of the Fifth Dynasty, during the regency of Neferirkara, the newly instituted throne name is also enclosed within a cartouche.

“The first occurrence of the use of cartouches to enclose queens’ names appears in the Sixth Dynasty. At this time we find the birth names of Ankhnesmeryra I and her sister Ankhnesmeryra II, also called Ankhnespepy—both wives of Pepy I— partially contained: cartouches enclose only the components “Meryra” and “Pepy,” these being the king’s throne and birth names, respectively. This convention reflects the queen’s position as “king’s wife,” but may further indicate, in a sense, that the king’s cartouche also became a part of the name of the queen, perhaps opening the way for queens to have their own names placed in cartouches. The name of queen Ankhnesmeryra I occurs in a private burial monument; that of Ankhnesmeryra II is found in her small pyramid at Saqqara. From the Middle Kingdom onward, cartouches enclosed the queen’s entire birth name; the birth name remained the only queen’s name to be enclosed by a cartouche. Occasionally epithets (both royal and non-royal) or god’s names could also be included.

“The cartouche remained in use until the end of Pharaonic civilization. When Pharaonic beliefs and the associated writing systems lost their relevance, the cartouche disappeared as well. The last pharaohs whose names are attested as written in cartouches are the Roman emperors Diocletian, Galerius, and Maximinus Daia of the beginning of the fourth century CE. The kings of Meroe in Sudan continued to use the cartouche until the fifth century CE.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Cartouches: Field Guide and Identification Key”

by John Sharp (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Way of Cartouche: an Oracle of Ancient Egyptian Magic”

by Murry Hope (1985) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Symbols: 50 New Discoveries” by Jonathan Meader and Barbara Demeter (2016) Amazon.com;

“Symbol & Magic in Egyptian Art” by Richard H. Wilkinson (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt: An Illustrated Dictionary” by Manfred Lurker (1984) Amazon.com;

“Myth and Symbol in Ancient Egypt” by Robert Thomas Rundle Clark Amazon.com;

“Esoterism and Symbol” by R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz (1985) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Religion an Interpretation” by Henri Frankfort (1948, 2011) Amazon.com;

Function and Meaning of Cartouches

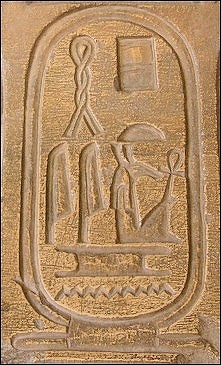

carthouche of Seti I (Sa-Re)

Cathie Spieser, an independent researcher in Switzerland, wrote: “The purpose of the cartouche is to protect the royal name, the name embodying, supernaturally, the ruler’s identity. Moreover, as a solar element depicting “all that the sun encircles,” the cartouche establishes a parallel between the sun and the pharaoh as long as he rules. [Source: Cathie Spieser, independent researcher, Switzerland, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The practice of encircling a written name to ensure its protection is ancient. In Predynastic times, a kind of cartouche formed by an elongated oval or square, sometimes crenellated and recalling the structure of a fortress, was employed to protect names of localities. A similar enclosure, the so-called serekh, or “palace façade,” was used from the First Dynasty onward to surround the king’s Horus name.

“The king’s throne and birth names enclosed in cartouches form a kind of heraldic motif expressing his dual nature: the birth name represents him on a terrestrial level as a human being, chosen by the gods, and the throne name represents him as an incarnation of divine power . The two cartouches may appear as a substitute for the anthropomorphic image of the king, but they are not its equivalent. When cartouches are used iconically, they reflect the king’s divine essence, in contrast to his anthropomorphic image, which is bound to his terrestrial aspect. Iconic cartouches could be worshipped by private individuals as an equivalent of the sun disc. They could also manifest the king in the role of various deities.”

Cartouches in Writing

Cathie Spieser wrote: “The cartouche isolates and foregrounds the name in a text while also magically ensuring the name’s protection. The cartouche could be written horizontally or vertically, with hieroglyphs oriented to the left or the right, or from top to bottom. [Source: Cathie Spieser, independent researcher, Switzerland, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The cartouche is generally preceded by a title referring to the enclosed name. The king’s throne name is entitled either nswt bjtj, “He of the sedge and the bee” (reading uncertain), mostly translated “King of Upper and Lower Egypt”/“Dual King” or nb tAwj, “Lord of the Two Lands.” His birth name is entitled either zA Ra, “Son of Ra,” or nb xaw, “Lord of Crowns/Appearances”.

“Most often one royal name is enclosed within a cartouche; however, from the end of the Sixth Dynasty through the Middle Kingdom sometimes two royal names are enclosed. In such cases the throne name precedes the birth name within the cartouche; sometimes the throne name is itself preceded in the cartouche by an epithet, such as nswt bjtj. From the Fourth Dynasty onward, it became the practice to include the epithet zA Ra within the cartouche of the king’s birth name. From the Ninth/Tenth Dynasties onward, the throne name could be preceded within the cartouche by the epithet nswt bjtj, but there is no discernable regularity or pattern in this practice. The regular inclusion of zA Ra within the cartouche is characteristic of the names of Eleventh Dynasty Theban kings. This practice survives only into the Hyksos Period and the Seventeenth Dynasty. The meaning of this feature is not clear; it may have been an attempt to endow royal names with greater sanctity, or, in the Eleventh Dynasty, it may have been an assertion of local identity.

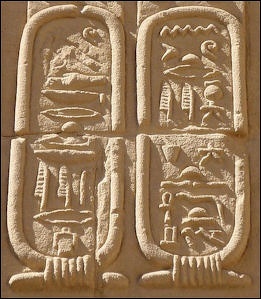

cartouche for the Roman leader Trajan

“From the New Kingdom onward, excluding some rare exceptions, non-royal epithets could occasionally be included in the cartouche, such as the title jt-nTr, used by the late Eighteenth Dynasty king Aye, or Hm-nTr, used by the high priests of Amun ruling in the Twenty-first Dynasty. An example of the latter practice is that of Herihor, whose throne name was Hm-nTr tpj n Jmn, “High Priest of Amun.”The use of cartouches was also sometimes extended to pharaohs whose names clearly evoked their non-royal origins, especially during the Second Intermediate Period. Examples include the birth names of kings Imiramesha, meaning “general” or “commander of the army”; Nehesi, meaning “the Nubian” or “a troop soldier”; and Shemesu, meaning “the escort”.

“From the end of the New Kingdom, a cartouche enclosing the name of a deity could also substitute for an anthropomorphicrepresentation of the god. Cartouches enclose, for example, the names of Osiris and Horus in their numerous variants, Horakhti, Amun- Ra, and Anubis, among others. A cartouche of a divinized king, such as Amenhotep I, functioned in a similar manner. Whereas the royal cartouche reveals some idea of the divinity of the king, the use of the cartouche for gods’ names displays an intent to bring the gods to a level closer to the human sphere. Gods’ names enclosed in cartouches appear, on the one hand, in a context deriving from royal ideology that associates them with the solar disc; on the other hand, they are also associated with the solar destiny of the deceased individual who is assimilated to the god. Many images displaying a cartouche enclosing a god’s name refer to Spell 16 of the Book of the Dead, especially in the iconography of post-New Kingdom Theban coffins.”

Cartouches Iconography and Ornamentation

Cathie Spieser wrote: “The cartouche takes on iconic significance when it appears in place of the anthropomorphic image of the king (or, much more rarely, the queen). It should be understood that in such cases the cartouche is not intended as a substitute for the ruler’s image but rather as a presentation of the ruler as a divine entity. One example shows Thutmose IV’s cartouche as a falcon with human arms—an iconic representation of “Horus slaying his enemies.” Similarly, artistic strategies serve to indicate when the replacement of the ruler’s image is intended. A cartouche of Thutmose III, worshipped by the viceroy of Kush called Nehy, is displayed on the same scale as Nehy himself. That the cartouche is ornamented further increases its sacredness. Additionally, gods or goddesses can be depicted protecting the cartouche. [Source: Cathie Spieser, independent researcher, Switzerland, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Cartouches can be assimilated with a god and venerated as such. The autonomous cartouche (i.e., the cartouche shown independently) presents the king or queen as the manifestation of various gods or goddesses, sometimes in combination with rebuses, cryptograms, and wordplay. The cartouche becomes a component of the Horus falcon in representations identifying the king with “Horus slaying his enemies”. The cartouche could also depict the king as Horus Behdety, replacing the solar disc between the god’s wings. The king’s name written within a solar disc or ouroboros (“the snake that bites its tail”) rather than a cartouche assimilates the king with the god Ra. The king’s name written in the solar bark likely associates the king with Amun-Ra; indeed the birth name of Amenhotep III can be written with the solar- bark sign, connoting Amun.

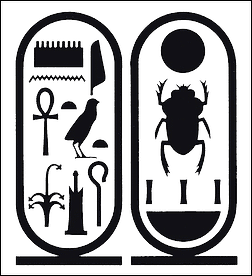

King Tut cartouche

“Ramesside royal sarcophagi in the form of a cartouche encircling the body of the king constitute a cosmogonic representation: they show the deceased king as Osiris enveloped by the bounded universe (“all that the sun encircles”). In such cases, the cartouche has an iconographic value but does not replace the image of the king. In the same way, the sarcophagus chambers from some earlier royal tombs—for example, the tombs of Thutmose I (KV38), Thutmose II (KV 42?), and Thutmose III (KV 34)—may take the form of a cartouche. The cartouche could also be used in the design of objects or furniture; for example, a wooden box in the form of a cartouche was found in Tutankhamen’s tomb. Cartouches, whether empty or enclosing a name, could serve as protective amulets, seals, and ring-seals, as displayed in the numerous examples found at el-Amarna.

“Ornaments served to protect the cartouche and to further emphasize the king’s or queen’s divinity. Some ornaments were placed atop the cartouche—we find cartouches surmounted by double-plumed solar discs, solar discs with or without a pair of uraei, and lunar discs, which in turn could be combined with ram, bull, or cow horns—whereas pairs of uraei with the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt are found adorning the sides. The cartouche can also occur without ornaments when it replaces the king’s or queen’s anthropomorphic image.

“The cartouche itself may surmount a potent associative symbol, such as the hieroglyph for “gold”, for “festival”, or for “the uniting of the Two Lands”, or the sign for the standard. The nbw-sign alludes to the “golden” radiance of the cartouche, considered an image of the sun disc. (In the Amarna Period, this solar radiance is reserved for the god Aten to the extent that the nbw-sign is excluded from iconography.) Moreover, the “nb” component of the nbw-sign perhaps also references “lord” and “all”—that is, the king as “ruler of all (the universe)”—constituting a display of multiple meanings. The Hb-sign may refer to the Sed Festival, the royal jubilee ritually celebrated by the king. The zmA- tAwj can bear one or multiple royal names. The jAt-sign is used to support many divinities and belongs to the emblems displaying the king’s (or queen’s) divine nature.”

Cartouche Veneration and Omission

Cathie Spieser wrote: “In the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.), cartouches in temple reliefs are shown receiving offerings from Nile gods, especially in procession scenes. New Kingdom iconography features scenes of officials venerating kings’ names. The officials express their loyalty to the king by praying to the king’s cartouche, which is itself assimilated with the rising sun; they also present funerary wishes, expressing their hope for continued existence in the afterlife. Starting in the reign of Hatshepsut, foreign chiefs are depicted prostrating before the ruler’s cartouches. A distinctive elaboration in the Ramesside Period is the veneration of cartouches by royal children. [Source:Cathie Spieser, independent researcher, Switzerland, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“An empty cartouche serves as a hieroglyphic determinative for the word rn (“name”) when it designates either the name of a ruler or the king’s titulary, rn wr (“great name”). In the Ptolomaic and Roman Periods, a great number of reliefs (at the temple of Dendara, for example) display an empty cartouche for either kings or queens, designating the kingship or queenship, respectively. The idea of kingship can also be expressed at this time by a cartouche containing only the word “pharaoh”, examples of which may point to weaknesses in, or uncertainty regarding, the kingship at this point in history.

cartouche of Nefertiti

“Some names of the royal titulary—the Horus name, Two Ladies name, and Golden Horus names, specifically—were never enclosed within a cartouche. The selective use of the cartouche in the titulary may have been a way to emphasize the sanctity of the throne and birth names. “Conversely, it is noteworthy that in the Ramesside Period the absence of a cartouche enclosing a royal name—in particular contexts—could actually indicate the name- holder’s increased status and divinity. Kings’ birth and throne names without cartouches are displayed, for example, in monumental friezes on temple walls. In statuary, officials are depicted holding the king’s hieroglyphic names in their hands—the absence of cartouches now lending iconic value to the hieroglyphs. It therefore appears that each hieroglyphic sign of the royal name had, by this time, taken on power and divinity individually. The signs still belonged to a cohesive grouping that constituted a royal name, but each simultaneously took on its own role as a divine entity.

“This is particularly visible in a frieze from the bark chamber in the Temple of Khons at Karnak. Here, alternating images of Ramesses IV, in maturity and as a young man, are shown offering maat to the god Amun, the name of the god being part of the king’s throne name. Close examination reveals that the frieze is a kind of rebus. One of the alternating images shows the king wearing the khepresh crown surmounted by a sun disc, heqa scepter in hand, offering maat to Amun, who sits atop the signs reading stp n—thus presenting the king’s throne name, HoA-mAat-Ra stp-n-Jmn. The other plays on the king’s birth name and is rather more difficult to read. Itfeatures the young king or prince surmounted by a sun disc, maat feather in hand, offering maat to Amun, who sits atop the mr-sign. Under both the young Ramesses and the god Amun is a double-s. In this way, the king’s birth name is presented: Ra-msj-sw HoA-mAat- mrj-Jmn. Thus, we see that the hieroglyphs themselves played an integral role in the artistic design of the frieze, the absence of the cartouche enhancing their iconic value. “

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024