Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CLOTHES

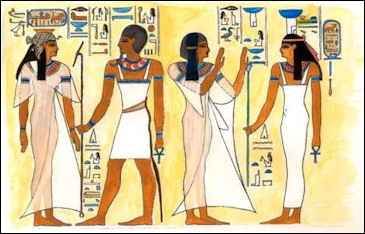

What we know about ancient Egyptian clothing styles is based primarily on images from tomb paintings, temple reliefs and grave goods. Withis this in mind, ancient Egyptians appear to have worn kilt-like, tunic-like and robe-like garments like those pictured in tomb painting. In many cases the garments worn by pharaohs and nobles wasn’t all that different from those worn by ordinary Egyptians. Egyptian clothes had no buttons or zippers. They were either tied or tucked.

What we know about ancient Egyptian clothing styles is based primarily on images from tomb paintings, temple reliefs and grave goods. Withis this in mind, ancient Egyptians appear to have worn kilt-like, tunic-like and robe-like garments like those pictured in tomb painting. In many cases the garments worn by pharaohs and nobles wasn’t all that different from those worn by ordinary Egyptians. Egyptian clothes had no buttons or zippers. They were either tied or tucked.

The various classes of ancient Egypt were distinguished by their clothes — the royal costume differed from that of the courtiers, and the household officials of the great lords were not dressed like the servants, the shepherds, or the boatmen. Commoner men (pyramid builders) wore loin clothes and women dressed in long sheaths attached above the breasts with a shoulder strap. Women also wore ankle-length skirts. The pharaoh’s kilt was called a “shendyt”.

Fashion also ruled: the costume of the higher classes was soon imitated by those next beneath them; it then was lost. For example, after the close of the 5th dynasty the old royal costume was imitated by the great lords of the kingdom, and later it passed down to be the official dress of the higher artisans; thus the same costume in which the courtiers of King Snefru appeared at court was worn not long afterwards by household officials. We must also add other distinctions; the old men wore longer warmer clothing than the young men, and for the king's presence men dressed better and more fashionably than for the home. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The clothes were depicted in tomb paintings were probably different than what people actually wore. For example, sculptures of women depict them wearing sexy, thin, tight-fitting garments while clothes excavated from graves tend be loose and smock-like. Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: “ The garments depicted in art do not correspond well to those discovered through archaeology, underscoring the idealization of pictorial representations. Clothing found in archaeological contexts is cut-to-shape or left in rectangular form from the loom, with long, loose tunics to be pulled on and off over the head, and many types of wraps, shawls, and mantles, which could be folded and knotted to yield different garment types. In art, tight-fitting dresses or diaphanous robes (for women), and kilts that mold to the buttocks but are voluminous in the front, hiding the genitals (for men), are more concerned with revealing and concealing parts of the body than accurately depicting the clothes that Egyptians wore. Similarly, the nudity of children and lower-status females is symbolic.” [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

See Separate Articles: WEAVING IN ANCIENT EGYPT: LINEN, LOOMS, GARMENT MAKING africame.factsanddetails.com ; JEWELRY IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian & Persian Costume” by Mary Galway Houston (1920) Amazon.com;

“History of Costume: From the Ancient Mesopotamians to the Twentieth Century” by Blanche, Payne (1997). Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Textiles” by Rosalind Hall (2008) Amazon.com;

“Textiles of Ancient Mesopotamia, Persia, and Egypt” by Florence Eloise Petzel (1987) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Textiles: Production, Crafts and Society” by Marie-Louise Nosch, C. Gillis (2007) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Tarkan Dress — the World’s Oldest Dress

Radiocarbon dating in 2016 of a dress discovered in Egypt in 1913 found it is at least 5,100 years old. According to Archaeology magazine: It’s almost impossible to imagine that an item of clothing worn thousands of years ago has survived to the present day. But the “Tarkhan Dress,” named for the town in Egypt where it was found, has endured. Researchers have determined that the very finely made linen apparel dates to between 3482 and 3103 B.C., making it the world’s oldest woven garment. Alice Stevenson, curator at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London, says, “The dress has provided people with a real sense of the antiquity and longevity of the ancient Egyptian state and society.” [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2017]

The Tarkhan Dress likely was worn by a young or slim female member of the royal court, and then placed in the tomb as a funerary object. Although the bottom does not survive, it may once have been full-length. Stevenson looked at the delicate cream-colored garment hundreds of times, wondering at both the fineness of its workmanship and its extraordinary age. It was once part of a large pile of dirty linen cloth excavated by Sir Flinders Petrie in 1913 at the site he named Tarkhan after a nearby village 30 miles from Cairo. In 1977, researchers from the Victoria and Albert Museum, while sorting through the pile of textiles as they prepared to clean them, discovered the dress, remarkably well preserved. They conserved the fabric, sewed it onto a type of extra-fine, transparent silk called Crepeline to stabilize it, and mounted it for display. The dress came to be known not only as Egypt’s oldest garment, but also as the oldest woven garment in existence. Yet in the absence of a precise original archaeological context — the mudbrick tomb in which the linen had been found had been plundered in antiquity — the exact age of the dress remained a subject of contention. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

“In 2015, Stevenson asked Michael Dee of the University of Oxford’s Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit to help her put the question to rest. Linen associated with the garment, but not the dress itself, had been dated in the 1980s to the late third millennium B.C. since the sample size required at the time might have damaged the garment. In addition, the precision of the accelerators used for radiocarbon dating is far greater today. Using sterilized tweezers and scissors, Stevenson took a tiny thread from the dress, a process she describes as nerve-racking. “You can’t help but envision the whole thing suddenly unraveling before you,” she says. In the case of linen, the smallest sample that can be tested corresponds to a piece of string about half a centimeter long, weighing between two and three milligrams. (The sample from the Tarkhan Dress weighed just 2. 24 milligrams. ) “You’re never pleased about removing a piece from an artifact, however small,” says Dee. “But it’s also exciting because you’re presented with the opportunity of confirming the item’s antiquity, and in many ways enhancing its cultural value. ” For example, another ancient Egyptian artifact Dee tested is the Ramses III Girdle, a woven linen waistband thought to date to the twelfth century B.C. Dee’s results corroborated that date, silencing rumors that the artifact might be a fake.

“Fortunately, linen is particularly easy to analyze. “Linen is a robust plant fiber composed of the carbon-rich biopolymer cellulose,” Dee explains. “This is much easier to handle and date than proteinaceous fibers like those found in wool and leather. ” Flax, from which linen is woven, also has a short growing time, making precise dating results easier to obtain. The major obstacle the team confronted was the size of the sample. “It was just so small,” Dee says, “so I am actually pleased, and somewhat surprised, we were able to produce a date. ”

“Perhaps even more surprising was the date itself — the Tarkhan Dress is from between 3482 and 3102 B.C., not only making it the oldest woven garment in the world, but also pushing the date of the linen back, perhaps to before Egypt’s 1st Dynasty (ca. 3111–2906 B.C.). “We’d always suspected it was old, and even if it wasn’t near the 1st Dynasty, even a 5th Dynasty dress [ca. 2500 B.C. ] is still pretty old by archaeological standards for this type of object,” says Stevenson. “But this new dating has affirmed my appreciation of the garment. With its pleated sleeves and bodice, together with the V-neck detail, it’s a very fine piece of clothing. There’s nothing quite like it anywhere of that quality and of that date. It’s amazing to think it has survived some 5,000 years. ”

Ancient Egyptian Skirts

The most ancient dress worn by persons of high rank seems to have been the simple short skirt which was the foundation of all later styles of dress. It consisted of a straight piece of white stuff, which was wrapped rather loosely round the hips, leaving the knees uncovered. As a rule it was put round the body from right to left, so that the edge came in the middle of the front. The upper end of this edge was stuck in behind the bow of the girdle which held the skirt together. In the beginning (Dynasty V), with the skirt unusually broad The skirt is white: That the girdle was separate from the skirt is probable bases on a picture. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

After the time of Khafre, the builder of the second pyramid, it became the fashion to wear the skirt longer and wider; at first this innovation came in with moderation, but towards the close of the 5th dynasty it exceeded good taste, and we can scarcely understand how a beau at the court of King Unas managed to wear this erection in front of him — perhaps he had a support to hold it out. Under the 6th dynasty we meet with the same costume though not so much exaggerated. The servants and peasants of this time began to wear their skirts wider, the household officials of the great lords having already set them an example in this direction.

There is a strange variation in this skirt, which appears to have been in much favor amongst the great lords of the 5th and 6th dynasties; by some artificial means they managed to make the front of the skirt stand out in a triangular erection. There were several slight differences in this fashion. If the edge of the skirt formed a loose fold it was regarded merely as a variation of the ordinary dress; if on the other hand the erection was quite symmetrical and reached above the girdle/ then it was considered to be quite a novel and quaint costume. We suspect that this erection (like a similar one in the New Kingdom) may have been a separate piece of stuff from the skirt, fastened on in front to the girdle.

In addition to these various forms of the short skirt, we meet with exceptional cases of men wearing long dresses, reaching from the waist to the feet. The deceased are represented in this dress when seated before the tables of offerings, receiving the homage of their friends still living; it is doubtless the dress of an old man, the same as was worn probably just before death.

Underwear in the Ancient World

People generally didn't wear underwear. Men and women sometimes went topless. Ordinary men often wore loin clothes and went bare chested. Even when women wore tops breasts were visible in the thin fabric.

Melissa Sartore wrote in National Geographic: Egyptians had schenti, Romans wore subligaculum...The earliest form of underwear was a loincloth. Prehistorically, loincloths were worn by men and women, crafted out of strips of fabric that ran between one's legs and were fastened around the waist. Ancient Egyptians fashioned triangular swatches of linen with strings at the ends. Modern observers may associate the look with a kilt, but the lengths of these schenti varied. Schenti were worn by pharaohs and, later, members of lower social classes. King Tut was actually entombed with 145 schenti, a large collection of loincloths to take with him to the underworld. [Source:Melissa Sartore, National Geographic, January 10, 2024]

Nudity was much more acceptable in ancient Greece, but even there, underwear comparable to that of the Egyptians called perizoma might be worn. Meanwhile, ancient Romans had their own undergarments to sport underneath a tunic, toga, or robe: Worn by the mid-2nd century A. D. and adapted from the ancient Etruscans, Roman subligaculum could resemble a loincloth or look more like a pair of shorts.

A tan, limestone statuette shows a male votary from the legs up with Cypriot loincloth and an Egyptian crown. It dates to the first half of the 6th century B.C. and measures 44. 5 x 21. 3 x 8. 6 centimeters (17 1/2 x 8 3/8 x 3 3/8 inches). A white statue of a woman with a gold bikini-like top and gold, bikini-like bottoms is a Roman marble copy of a Hellenistic original found in the House of Julia Felix (Praedia di Giulia Felice) in Pompeii (A.D. 1st century). It is on display in the Secret Cabinet (Gabinetto Segreto) in the National Archaeological Museum in. Naples. Her arm is resting on the head of a child, also in statue form. A smaller child is seen crouched down under her foot, holding up it's hand to touch the foot.

Royal and Upper Clothing in Ancient Egypt

Well-preserved clothes found in King Tut tomb include lose-fitting, sleeveless tunics worn over loin clothes, linen belts, jeweled sandals made of reed, white loin cloths and head scarves. Some of the fabrics were plain white and others were embroidered with red, yellow and blue threads and studded with gold. Scientists were able confirm the boy-kings age from a small, delicate, linen cloth.

A lion's tail with the ends rounded off that hung down from the skirt of the Pharaoh was one of the most ancient symbols of royalty. Another indication of high rank were strips of white material which great lords of the Old Kingdom often wound round the breast or body when they put on their gala dress; or allowed to hang down from the shoulders," when in their usual dress they went for a walk in the country; or when they went hunting. A broad band of this kind was no protection against the cold or the wind, it was rather a token by which the lord might be recognized. In the same way the overseer of the fishermen or laborers was known by a narrow band round the neck. The narrow ribbons, which we so often see great men of all periods holding between their fingers, may have the same signification. ' [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In addition to these-every-day costumes, the great lords of the Old Kingdom possessed one intended only for festivals. As is usual in such cases, this festive costume does not resemble the fashionable dress of the time, but follows the more ancient style. It is in fact merely a more elegant form of the old, narrow, short skirt; the front is rounded off so that it falls in little folds, and the belt is fastened by a pretty metal clasp. In spite of numerous representations, it is difficult to see how this clasp was made; the narrow ornamented piece, which is nearly always raised above it, is perhaps the end of the girdle; it is certainly not the handle of a dagger, as has been generally supposed. Finally, the forepart from the middle of the back was often further adorned by a pleated piece of gold material, thus forming a very smart costume. To complete this festive garb a panther skin was necessary, which was thrown over the shoulders by the great lords when they appeared in “full dress. " The right way of wearing this skin was with the small head and fore paws of the animal hanging down, and the hind paws tied together with long ribbons over the shoulder. It was the fashion, when sitting idle, to play with these ribbons with the left hand. "

In the gala costume of this period the outer skirt grew to be of less significance than the inner. The latter developed into a wide pleated dress, whilst the former retrograded into a piece of linen folded round the hips. At the same time we find very various costumes in the representations — sometimes the piece of linen is wrapped round the body in such a way as to cover the back of the legs behind and yet to be quite short in front; sometimes it assumes the form of the ancient skirt; sometimes it is wound twice or thrice round the body. In several pictures the shirt appears to open up on both sides, and to be sleeveless, whilst at the same time, in other postures of the arm, the sleeve is plainly visible. Again in figures standing facing the right, the disposition of the dress in the pictures is changed, and the sleeve appears on the right arm. Shirts with two distinct sleeves are rare, though the governor of Ethiopia certainly wears one.

The dress of the great lords of the 19th dynasty corresponds very nearly to that of the great men of the time of Akhenaten described above, except that the puffs of the outer skirt were smoothed out, and that it was worn somewhat longer during the later period. In the time of Ramses III. a fashion was adopted which had already been employed for festive garments; the outer skirt, which was only used for ornamental purposes, was entirely given up, and a broad piece of material, cut in various shapes, was fastened on in front like an apron. Meanwhile the clothing of the upper part of the body remained essentially the same, though after the time of the 19th dynasty it was worn fuller than before. We sometimes find also a kind of mantle, which fits the back closely and is fastened together in front of the chest. The kings usually appear in it; other people only wear it on festive occasions.

The great lords tried as far as possible to dress like the Pharaoh. The festive costume of the Old Kingdom was the first result of imitation; the edge in the front of the skirt was rounded off and adorned with golden embroidery, so that the wearer should in his dress, when seen at any rate from the right side, resemble His Majesty. It is only towards the close of the 5th dynasty that we first occasionally meet with a costume exactly resembling the royal skirt, except that it was not made of gold material nor furnished with a lion's tail. It was worn as a hunting costume under the Middle Kingdom as well as in the beginning of the New Kingdom, when men of high rank wore it when hunting birds or spearing fish. "

Under the Middle Kingdom however it appears that a law was passed limiting such imitations, and the wearing of the shendyt (the royal skirt) was only granted to certain dignitaries. Many great lords of the 12th dynasty expressly claim this privilege, and in later times the high priests of the great sanctuaries bear as one of their proudest titles wearer of the shendyt. These limitations were not of much use, and in the time of confusion between the Middle and the New Kingdom the royal skirt was adopted by an even wider circle. Under the 18th dynasty the chiefs of all the departments wore it on official occasions, and even when they gave way to the fashion of the time and wore an outer long skirt, they fastened the latter up high enough for the symbol of their office to be visible underneath. Officials whose duties were very circumscribed, such as the “chief of the peasants," or the “chief of the waggoners," chief masons, sailors, and drivers of the time of the New Kingdom, often wore skirts very much resembling the shendyt.

Another dress, seen at the first glance to be a robe of office, is that of the chief judge and governor, who was the highest official of the Egyptian government; he wore a narrow dress reaching from the breast to the ankle, held up by two bands fastened with a metal clasp behind at the neck. This great lord wore his head shaven like the priests — probably because he was also the high priest of the goddess of truth. '' We shall speak later of the many changes in the dress of the priests and of the soldiers.

Women’s Clothing in Ancient Egypt

In tomb art women are portrayed as tall and bosomy. They were often elaborately dressed and sometimes wore tight dresses that left one breast exposed. Ordinary women dressed in long sheaths attached above the breasts with a shoulder strap. In the oldest dynasties at least it seems that men were more absorbed in fine clothes than women. Compared with the manifold costumes for men, the women's dress appears to us very monotonous, for during the centuries from the 4th to the 18th dynasty, the whole nation, from the princess to the peasant, wore the same dress. This consisted of a simple garment without folds, so narrow that the forms of the body were plainly visible. It reached from below the breasts to the ankles; two braces passed over the shoulders and held it up firmly. In rare instances the latter are absent,'' so that the dress is only prevented from slipping down by its narrowness. The dress and braces are always of the same color, white, red, or yellow; in this respect also there existed no difference between that of mother and daughter, or between that of mistress and maid. In the same way all wore it quite plain, unless perhaps the hem at the top might be somewhat embroidered. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

It is very rarely, as we have said, that we find dresses of a different fashion. 'Et'e, wife of Sechemka, the superintendent of agriculture, wears a white dress richly embroidered with colored beads, covering the breasts and cut down in a V between them. It is worn with a belt and has therefore no braces. Another dress, which we find rather more frequently, covers the shoulders though it has no sleeves; the neck also is generally cut down in a V. In the following illustration, representing the beautiful statue of Nofret, the wife of the high priest Rahotep, is seen a cloak which is worn over the usual dress.

Under the Middle Kingdom women's dress seems to have changed but little, and in the beginning also of the 18th dynasty the modifications were but trifling; contemporary however with the changes in men's dress which followed, it assumed a new character, due partly to the great political change in the position of Egypt in the world. Following the new fashions of the day, women wore two articles of clothing — a narrow dress leaving the right shoulder free, but covering the left, and a wide cloak fastened in front over the breast; as a rule both were made of such fine linen that the forms of the body were plainly visible. The hem of the cloak was embroidered, and, when the wearer was standing still, hung straight down. In course of time, under the New Kingdom, this costume evidently underwent many changes, all the details of which are very difficult to follow, because of the superficial way in which the Egyptian artist represented dress. On every side we are liable to make mistakes. If we, for instance, take the picture here given of the Princess Beketaten by itself we should conclude that the lady was wearing a single white garment, it is only when we compare it with the more detailed contemporary picture of a queen that it is possible rightly to understand it. In both cases the same dress and cloak are worn; but while in the one case the artist has given the contours of both articles of dress, in the other he has lightly sketched in the outer edges only, and thus as it were given the dress in profile. Even then he is not consistent; he shows where it is cut out at the neck and where the cloak falls over the left arm, but he quite ignores that it must cover part of the right arm also.

The next development, in the 19th and 20th dynasties, was to let the cloak fall freely over the arms as shown in the accompanying illustration; ' soon afterwards a short sleeve was added for the left arm, whilst the right still remained free. Finally, towards the close of the 20th dynasty, a thick underdress was added to the semi-transparent dress and the open cloak. We have one costume which deviates much from the usual type, and which belongs certainly to the second half of the New Kingdom; it is seen on one of the most beautiful statues in the Berlin museum; it consists of a long dress which seems to have two sleeves, a short mantilla trimmed with fringe on the shoulders, and in front a sort of apron which falls loosely from the neck to the feet. We noticed above the dress of a man in which in similar wise a kind of apron hung down from the belt: the representation of the husband of this lady shows us that both these fashions were in vogue at the same time. Contemporary with the complicated forms of female costume we sometimes meet with a very simple one, a plain shirt with short sleeves, reaching up to the neck; this, however, seems only to have been worn by servants. ''

Considered as a whole, the development of female dress followed very much the same course as that of the men. In both cases under the Old Kingdom the forms were very simple; there was little change until the beginning of the New Kingdom, at which time, with the great rise of political power, there was a complete revolution in dress. In both cases the change consisted in the introduction of a second article of clothing, and the two new dresses correspond with each other in possessing a sleeve for the left arm only, while the right arm is left free for work.

Lower Class Clothing in Ancient Egypt

Peasants, shepherds, workmen, servants always contented themselves with a very simple costume. When dressed for the presence of their master they generally wore a short skirt of the kind that was fashionable at the beginning of the 4th dynasty. '' When at work it was put on more loosely, and with any violent movement it flapped widely apart in front." Subordinate officials were behind the time. In the Middle Kingdom they wore the short skirt of the Old Kingdom, and under the New Kingdom the longer one of the Middle Kingdom. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

This skirt was generally of linen; yet certain shepherds and boatmen of the Old Kingdom appear to have contented themselves with a clothing of matting; these men are remarkable also for the curious way of wearing their hair and beard, corresponding to that of the oft-mentioned i/iarsh

The laborers of the New Kingdom also wore rough skirts of matting, which they were wont to seat with a piece of leather. ' Finally, people who had to move about much, or to work on the water, wore nothing but a fringed girdle of the most simple form — a narrow strip of stuff with a few ribbons or the end of the strip itself hanging down in front. A girdle of this kind could not, of course, cover the body much, the ribbons were displaced with every movement, and the boatmen, fishermen, shepherds, and butchers often gave it up and worked in Nature's costume alone. The feeling of shame so strongly developed with us did not exist in ancient Egypt; the most common signs in hieroglyphics sometimes represented things, now not usually drawn.

The dress of the women of the lower classes never differed much from that of the ladies; peasant women and servants for the most part wore clothes of almost the same style as those of their mistresses. Their dress allowed of very little movement, and could not therefore be worn for hard work — at such times women like men were contented to wear a short skirt which left the upper part of the body and the legs free.

The dancing girls of ancient times, doubtless from coquettish reasons, were wont to prefer the latter dress decked out with all sorts of ornaments rather than a more womanly costume. For similar reasons the young slaves under the New Kingdom, who served the lords and ladies at feasts, wore as their only article of clothing a strip of leather which passed between the legs, and was held up by an embroidered belt (see the two plates in the following chapter); the guests liked to see the pretty forms of the maidens.

Ancient Egyptian Shoes, Sandals and Hats

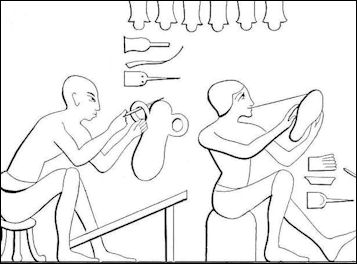

cobblers at work Ancient shoes where generally made from woven palm leaves, vegetable fibre or papyrus and were kept in place on the foot with linen or leather bands. Some of the earliest known shoes from the Old World are sandals made from papyrus leaves found in an Egyptian tomb dated at 2000 B.C. A leather sandal dated to 1300 B.C. has also been found in Egypt. Sandal-makers depicted in tomb paintings went about their duties like 19th century cobblers.

Sandals and shoes were worn mainly the rich. One very old image shows a nobleman walking barefoot followed by a servant carrying his shoes. Ordinary people often went barefoot. Egyptians exchanged sandals when they exchanged property or authority. A sandal was given to a groom by the father of the bride.

Egyptians generally didn't wear hats it seems. They sometimes wore hair bands to keep their hair out of their face of wigs. Egyptian noblemen used parasols, carried by slaves for protection from the sun. The Egyptians didn't need gloves for warmth, but women wore soft linen gloves, sometimes embroidered with colored threads, as a decorative accessory. Children often went nude until they were teenagers.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN SHOES, HATS AND LEATHERWORKING africame.factsanddetails.com

Fashion and Changes in Clothing Styles in Ancient Egypt

From what can be determined, the Egyptian upper classes were very fashion conscious. Much effort went into preparing their clothes and the hairstyles, which appeared to changed often over the centuries. Over time the kilts and tunics became long and fuller. In the Ramses II era men and women wore elaborately pleated layers of starched linen. Some women are believed to have worn live snakes around their necks. Some elite New Kingdom women wore form-fitting dresses of pleated linen. Linen undergarments were found in King Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Under the Old Kingdom a short skirt was worn round the hips; under the Middle Kingdom a second was added; and under the New Kingdom the breast also was covered. If we look closer we find many other changes within these great epochs. If during one century the skirt was worn short and narrow, during the next it would be worn wide and shapeless, whilst during a third it was fashionable only when peculiarly folded. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Between the 6th and 12th dynasties, dress underwent no great change; the skirt meanwhile became a little longer, so that it reached to the middle of the leg. Under the Middle Kingdom it again became narrower and less stiff; for this purpose it was slightly sloped in front, and hung rather lower between the legs. If possible, it was the right thing to show one or two points, which belonged to the inner part of the skirt. ' Men also liked to decorate the outer edge with an embroidered border, or to pleat it in front prettily. Ordinary people wore this skirt of thick material, but men of high rank, on the contrary, chose fine white material so transparent that it revealed rather than concealed the form of the body. It was then necessary to wear a second skirt under the transparent outer one. Those who had the right to wear the Shendyt, the short royal dress, liked to wear it as the inner skirt. Contemporary with this double skirt, which marks a new epoch in the history of Egyptian dress, appears the first clothing for the upper part of the body. One of the princes of the Nome of the Hare, who were buried at Bersheh, wears, as is seen in the illustration below, a kind of mantilla fastened together over the chest. - In a second representation the same lord appears in a most unusual costume; he is wrapped from head to foot in a narrow dress apparently striped; such a dress seems to have been worn by old men under the Middle Kingdom. "

Nefertari During the interval between the Middle and the New Kingdom there was little innovation in dress, but the more stylish forms of men's clothing entirely superseded the simpler fashions. The priests alone kept to the simple skirt; all other persons wore an outer The rapid development of the Egyptian Empire, and the complete revolution in all former conditions, soon brought in also a quick change of fashion. About the time of Queen Chnemtamun dress assumed a new character. It became customary to clothe the upper part of the body also, a short shirt firmly fastened under the girdle was adopted now as an indispensable article of dress by all members of the upper class; the priests alone never followed this fashion. To promote free movement of the right arm this shirt appears to have been open on the right side, while the left arm passed through a short sleeve. During this period each generation adopted its own particular form of skirt. At first the inner skirt remained unchanged whilst the outer one was shortened in front and lengthened behind. Towards the close of the 18th dynasty, under the heretic king Akhenaten, the inner skirt was worn wider and longer, whilst the upper one was looped up in puffs, so as to show the under one below it. The front of the outer one was formed of thick pleats, the inner one also was often pleated, and the long ends of the girdle were allowed to hang down.

Another remarkable coincidence is that at the same time in the clothing of both sexes appearance seems so much to have been studied. It is quite possible that these changes were effected in some degree by foreign intercourse — how far this was the case we cannot now determine. This influence, however, could only have affected details, for the general character of Egyptian dress is in direct contrast to that which we meet with at the same time in North Syria. The Syrians wore narrow, closefitting, plain clothes in which dark blue threads alternated with dark red, and these were generally adorned with rich embroidery.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024