Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

NEW KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT

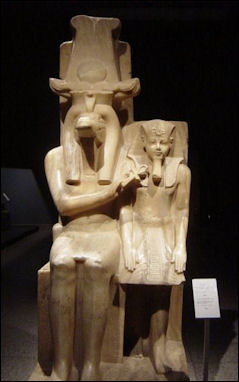

Amenhotep III and Sobek The New Kingdom lasted from around 1550 to 1070 B.C. and encompassed dynasties 18 to 20. This period began after the Hyksos were defeated by a series of Egyptian rulers and the Upper and Lower Egypt were reunited. The New Kingdom was when when many Egyptian rulers were buried in the Valley of the Kings and King Tutankhamun (King Tut, 1336–1327 B.C.) lived. By this time the pharaohs had stopped building pyramids. They stopped for a variety of reasons including to provide better security to thwart tomb robbers. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

Around the year 1600 B.C., late in the Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1640–1550 B.C.), the semi-autonomous Theban 17th dynasty under the suzerainty of the Hyksos became determined to drive the Hyksos kings of Dynasty 15 from the Nile Delta. This was finally accomplished by Ahmose I (ruled 1570-1546 B.C.), the son of the last ruler of the Seventeenth Dynasty. Ahmose I reunited Egypt, ushering in the New Kingdom—the third great era of Egyptian culture. The New Kingdom lasted to the death of Ramses IX around 1050 B.C. and embraced 32 pharaohs and ruled territories from Nubia to Asia. But by the end of this period Egypt was overwhelmed by internal troubles and had lost control of all of its foreign territories. Never again would Egypt enjoy such splendor.

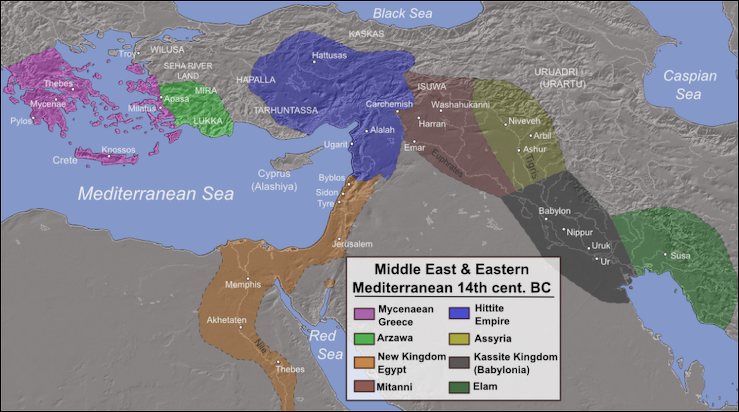

During the New Kingdom, Egypt reached the peak of its power, wealth, and was a superpower in the Middle East. The government was reorganized into a military state with an administration centralized in the hands of the pharaoh and his chief minister. Through the intensive military campaigns of Pharaoh Thutmose III (1490-1436 B.C.), Palestine, Syria, and the northern Euphrates area in Mesopotamia were brought within the New Kingdom. This territorial expansion involved Egypt in a complicated system of diplomacy, alliances, and treaties. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

During New Kingdom, Egypt had a populations of 1 million to 1.5 million. The pharaohs, for the most part, resided in Memphis (near Cairo) and visited Thebes — which was primarily a religious center — to perform rituals. During the New Kingdom, the Egyptian empire extended southward to the land of Punt (Somalia) and the 5th Cataract near present-day Khartoum, Sudan, and eastward across the Middle East past Palestine and Syria to the Euphrates River of Mesopotamia. The powerful Hittites and Mitanni in the north at various times were both enemies and allies. Assyria and Babylon sent tributes. After Thutmose III established the empire, succeeding pharaohs frequently engaged in warfare to defend the state against the pressures of Libyans from the west, Nubians and Ethiopians (Kushites) from the south, Hittites from the east, and Philistines (sea people) from the Aegean-Mediterranean region of the north.

See Separate Article: RULERS OF THE NEW KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT (1550–1070 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt: A Captivating Guide” Amazon.com;

“Local Elites and Central Power in Egypt during the New Kingdom”

by Marcella Trapani Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

"The New Kingdom" by Wilbur Smith, Novel (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Late New Kingdom in Egypt (c. 1300–664 BC) A Genealogical and Chronological Investigation (Oxbow Classics in Egyptology) by M. L. Bierbrier (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt:The Definitive Visual History” by Steven R. Snape (2021) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of Ancient Egypt” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” (DK Eyewitness Books) by George Hart (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East” by Amanda H Podany (2022) Amazon.com;

New Kingdom Achievements

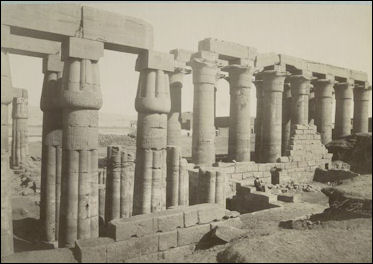

The New Kingdom was the golden age of ancient Egypt and the era of the great pharaohs. Culture and the arts blossomed, great temples and colossal monuments were raised, great works of art were created, prosperity reigned. The New Kingdom capital was at Thebes (present-day Luxor), where the great temples of Karnak and Luxor were built and the pharaohs were buried in the Valley of the Kings.

The New Kingdom was a period of nearly 500 years of political stability and economic prosperity. Catharine H. Roehrig of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: Dynasty 18 pharaohs conducted military campaigns that extended Egypt's influence in the Near East and established Egyptian control of Nubia to the fourth cataract. As a result, the New Kingdom pharaohs commanded unimaginable wealth, much of which they lavished on their gods, especially Amun-Re of Thebes, whose cult temple at Karnak was augmented by succeeding generations of rulers and filled with votive statues commissioned by kings and courtiers alike. [Source: Catharine H. Roehrig, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org ]

Although the rulers of Dynasty 19 established an administrative capital near their home in the Delta, Thebes remained a cultural and religious center. The cult of the sun god Ra became increasingly important until it evolved into the uncompromising monotheism of Pharaoh Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV, 1364-1347 B.C.). According to the cult, Ra created himself from a primeval mound in the shape of a pyramid and then created all other gods. Thus, Ra was not only the sun god, he was also the universe, having created himself from himself. Ra was invoked as Aten or the Great Disc that illuminated the world of the living and the dead.[Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

Famed Egyptologist Zahi Hawas told Smithsonian magazine, “This period was like a fantastic play with magnificent actors and actresses. Look at the beautiful Nefertiti and her six daughters. King Tut married one of them. Look at her husband, the heretic monarch Akhenaten; his domineering father, Amenhotep III and his powerful mother Queen Tyre. Look at the people around them, Maya, the treasurer; Ay the power behind the throne; and Horemheb, the ruthless general.”

New Kingdom Art and Architecture

Amenhote Luxor Temple Known especially for monumental architecture and statuary honoring the gods and pharaohs, the New Kingdom also produced an abundance of artistic masterpieces created for use by nonroyal individuals. As historian Cyril Aldred has said, the civilization of the New Kingdom seems the most golden of all the epochs of Egyptian history, perhaps because so much of its wealth remains. The rich store of treasures from the tomb of Tutankhamen (1347-1337 B.C.) gives us a glimpse of the dazzling court art of the period and the skills of the artisans of the day. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

One of the innovations of the period was the construction of rock tombs for the pharaohs and the elite. Around 1500 B.C., Pharaoh Amenophis I abandoned the pyramid in favor of a rock-hewn tomb in the crags of western Thebes (present-day Luxor). His example was followed by his successors, who for the next four centuries cut their tombs in the Valley of the Kings and built their mortuary temples on the plain below. Other wadis or river valleys were subsequently used for the tombs of queens and princes. The huge rock-cut tombs decorated with finely executed paintings or painted reliefs illustrating religious texts concerned with the afterlife. A town was established in western Thebes for the artists who created these tombs. At this site (Deir el-Medina), they left a wealth of information about life in an ancient Egyptian community of artisans and craftsmen. \^/

Another New Kingdom innovation was temple building, which began with Queen Hatshepsut, who as the heiress queen seized power in default of male claimants to the throne. She was particularly devoted to the worship of the god Amun, whose cult was centered at Thebes. She built a splendid temple dedicated to him and to her own funerary cult at Dayr al Bahri in western Thebes.*

One of the greatest temples still standing is that of Pharaoh Amenophis III at Thebes. With Amenophis III, statuary on an enormous scale makes its appearance. The most notable is the pair of colossi, the so-called Colossi of Memnon, which still dominate the Theban plain before the vanished portal of his funerary temple.*

Ramesses II was the most vigorous builder to wear the double crown of Egypt. Nearly half the temples remaining in Egypt date from his reign. Some of his constructions include his mortuary temple at Thebes, popularly known as the Ramesseum; the huge hypostyle hall at Karnak, the rock-hewn temple at Abu Simbel (Abu Sunbul); and his new capital city of Pi Ramesses.*

Thebes (Luxor)

The New Kingdom capital was at Thebes (present-day Luxor), about 500 kilometers (310 miles) south of present-day Cairo. Luxor is an Arab name that means "City of Palaces." Located on a sweeping bend in the Nile, it boasts some of most famous temples in Egypt and is the second largest draw in Egypt after Cairo and the Pyramids, Luxor is home to the greatest concentration of ancient monuments in Egypt: the magnificent temples of Karnak, Luxor and Hatshepsut , the Valley of the Kings, the Valley of the Queens, the tomb of Tutankhamen, and the Colossi of Memnon, the giant broken statues of Ramses the Great that inspired Shelley's poem “Ozymandias”.

Thebes is a Greek name which means "the one hundred gated city." Embracing the area occupied by Karnak and Luxor, it was the erstwhile capital of Egypt, and for more than 1,000 years. From 2,100 to 750 B.C., Thebes was the religious capital of Pharonic Egypt and the center of Egyptian power. Pharaohs erected monuments, temples and sculptures as testaments to their wealth, power and piety. The priests who worked out of the temples became so powerful they were regarded as a threat to the pharaoh. The New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 B.C.), which many scholars believe was the cultural and artistic zenith of Egyptian civilization, was an especially prolific period in Thebes. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

Thebes emerged as the main power center of Egypt at the dawn of the Middle Kingdom (2125 to 1520 B.C.) and became the capital of Egypt after the Hyksos were kicked out of Egypt. During the New Kingdom (1539 to 1075 B.C.) it was the center of Egypt. The pharaohs resided here and perhaps 1 million people lived in the area. The largest and most spectacular building were built during the reigns of Amenhotep III and Ramses II in the 14th and 13th century B.C. By Greco-Roman times it was already major tourist attraction.

East Bank of the Nile at Thebes (Luxor)

The East Bank of the Nile in Luxor is where the pharaoh lived, temples were built and the city that served the pharaoh grew up. Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The banks of the Nile River in modern-day Luxor are strewn with so many ruins of Egypt’s illustrious past that the area is sometimes called the world’s largest open-air museum. Among the archaeological sites on the Nile’s east bank are two of the largest and most important temples in all of Egypt, the Karnak Temple, called the “most selected of places” by ancient Egyptians, and the Luxor Temple, known to them as the “southern sanctuary.” [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

These two massive religious complexes, both of which celebrated the holy Theban trinity of Amun-Ra, the greatest of gods, his consort Mut, and their son Khonsu, still boast reminders of their former glory — ornate columns, giant statues, soaring obelisks, and expertly carved reliefs. The complexes were connected by an almost two-mile-long grand processional way known as the Avenue of Sphinxes, lined with more than 600 ram-headed statues and sphinxes carved in stone.

The Temple of Karnak (2 miles north of Luxor) ranks with the Pyramids as most amazing site in Egypt and by some estimates is the largest religious structure ever created. Over two millennia it was enlarged and enriched by consecutive pharaohs until it covered 247 acres of land on the Nile’s east bank. At its height it stretched over an area of one mile by a half a mile — about half the size Manhattan — and was like a city, containing its own administrative offices, palaces, treasuries bakeries, breweries, granaries and schools. "Karnak" is the Arabic word for fort. It used to be called Ipetesut — “most esteemed of places.”

See Separate Article: KARNAK TEMPLE: ITS HISTORY, COMPONENTS AND GREAT HYPOSTYLE HALL africame.factsanddetails.com

Amenhotep I

West Bank of the Nile at Thebes (Luxor)

The West Bank of the Nile in Luxor is where many New Kingdom pharaohs, their wives, their children, important priest and nobles, and even ordinary workers were placed in tombs that prepared for their journey to next world. There are a few temples and monuments here. Most of them are associated with dead.

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The most prominent archaeological remnants on the west bank, an area known to scholars as the “city of the dead,” are a group of mortuary temples built by some of the New Kingdom’s most notable rulers, including Hatshepsut (r. ca. 1479–1458 B.C.), Ramesses II (r. ca. 1279–1213 B.C.), and Ramesses III (r. ca. 1184–1153 B.C.). Mortuary or funerary temples were not where pharaohs were entombed, but where they were commemorated and worshipped for eternity after their deaths, alongside other Egyptian gods. Dwarfing all these complexes was the one known to have been built by Amenhotep III (r. ca. 1390–1352 B.C.). [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

Inland from the West Bank of the Nile is the Valley of the Kings is the burial ground of the pharaohs of the New Kingdom, which ruled around 1500 B.C. to 1100 B.C. Known to the ancient Egyptians as “The Great and Majestic Necropolis,” the valley is surrounded by barren mountains, with largest being Al-Qurn (the Horn).

See Separate Article: VALLEY OF THE KINGS africame.factsanddetails.com

New Kingdom Government

The Old Kingdom and Middle Kingdom was a time of decentralization. The numerous small districts into which the country was split had their own courts of justice, their own storehouses for corn, and their own militia. During the New Kingdom Egypt became more unified under a central government.

During the New Kingdom, the constitution of the state must be regarded as a new creation. Many of the old courts of jurisdiction and many titles still existed, but the fundamental principles of the government were so much changed that these resemblances could only be external. In the first place, during the New Kingdom the provincial governments on which the old state rested have entirely disappeared; there are no longer any nomarchs; the old aristocracy has made way for royal officials, and the landed property has passed out of the hands of the old families into the possession of the crown and of the great temples. This is doubtless the effect of the rule of the Hyksos and of their wars. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

There was no lack of priests in the older time, but, with the exception of the high priests of the great gods, most of the priesthood held inferior positions bestowed upon them by the nomarchs (province leaders) and by the high officials. We hear but little also of the estates or of the riches of the temples; at most we only meet with the “treasurer “of a sanctuary. During the Middle Kingdom the conditions are somewhat different: we find a “scribe of the sacrifices,"" and a "superintendent of the temple property,"' a “lord treasurer of the temple," and even a “scribe of the grain accounts and superintendent of the granaries of the gods of Thinis. "

The above however were of little importance compared to the numberless “superintendents of the cabinet," and the “keepers of the house," belonging to the treasury. During the New Kingdom all is changed; the fourth part of all the tombs at Abydos belong to priests or to temple officials. The individual divinities have special superintendents for their property," for their fields, for their cattle, for their granaries, and for their storehouses, they have directors for their buildings,' as well as their own painters and goldsmiths, their servants and slaves, and even the chief barber has his place in all the great sanctuaries.

The old nomarch title of “prince “is also still borne by the governors of great towns such as Thebes or Thinis,' but they have lost the influence and power which these princes possessed under the Middle Kingdom. They have become purely government officials without any political significance; Thebes possessed two of these princes, one for the town proper, the other for the quarter of the dead. If we may trust a representation of the time of Seti I., the “south and the north “were formerly governed by 19 princes. "

New Kingdom Military

During the New Kingdom, Egypt had a strong military. The kingdom’s borders were expanded and the the military rose to greater power than ever before. During the Middle Kingdom the Nubian wars were carried on by the militia of the individual nomes; one element of a standing army alone was present — the “followers of the king " [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Every thing seems changed under the New Kingdom: we continually meet with the infantry, the chariot-force with their officers, and the “royal scribes "; on the borders and in the conquered country we find mercenaries with their chiefs, while in the interior were foreign troops and mercenaries. For the most part these warlike services are rendered to Pharaoh by foreigners, and under Ramses II. we meet with Libyans and Shardana in Egyptian pay.

It follows that an army of mercenaries, such as we have described, would soon become a powerful factor in the state, and would interfere in many ways in the government. That this was the case we can often gather from the correspondence of the scribes which is still extant. The “chief of the soldiers “orders exactly how and where a certain canal is to be dug, and his deputy not only orders blocks of stone to be transported, but also undertakes the transport of a statue. ' The king's charioteer, holding a high position in the army, watches over the transport of monuments, and the chief of the militia does the same. With this we can also see that officers of the army have stepped into the places of the former “high treasurer," and of the “treasurer of the god. "

War, Trade and Expansion During the New Kingdom

The New Kingdom was a period of Egyptian expansion and imperialism. According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: In the earlier periods Egypt's contact with, and control over, foreign areas was limited to her desire for trade and resources; during the New Kingdom Egypt's foreign policy became more aggressive. The Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni became a threat to Egypt, and the New Kingdom rulers responded to Mitanni's rising power in the area. [Source:Encyclopaedia Judaica, Thomson Gale, 2007]

The 18th Dynasty ruler Thutmose I led a campaign into northern Syria. Later, Thutmose III led 14 campaigns into Western Asia (one of which included a seven-month siege at Megiddo), and eventually subdued the Levantine coast, increasing Egyptian hegemony into the interior of Syro-Palestine. Under Thutmose III the rulers of the conquered Asiatic city-states became vassals to Egypt who had to send tribute and swear an oath of loyalty to the Pharaoh. True peace was not realized until the reign of Thutmose IV, who married one of the Mitannian princesses. “The Egyptian Empire reached its height during the reign of another 18th Dynasty Pharaoh, Amenhotep III. By this time the empire was firmly established, so that Egypt was able to keep her troops in just a few areas and to send garrisons only to regions that threatened revolt. But this relative ease of imperialism was short lived, and the Empire began to falter under the reign of Amenhotep IV.

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The 2nd Intermediate Period came to a close with the defeat of the Hyksos by Ahmose I. After securing Egypt's northern borders, Ahmose I instituted internal changes. He created a the position of Viceroy for Kush, Nubia. This Viceroy answered to no one but the Pharaoh. The wars of this period were fought with the powerful Near East empires, such as the Hittites, the Mitanni and the Assyrians, all of which were neighbors of Egypt. The Mitanni occupied an area around Nahrina. The Assyrians were on the eastern border and the Hittites occupied the land to the west. Also during this time period, Ramesses III fought against a coalition of wandering tribes called the Sea Peoples. This saw the borders of Egypt expand in the north as far as the Euphrates River and down to the 4th cataract in the south. These borders would then retract until Egypt was nothing more than the Nile Valley extending down to the 2nd cataract. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“It was Tuthmosis I who extended the borders of Egypt to their farthest extent. He and his grandson, Tuthmosis III, then fought many campaigns to hold onto these borders. Later in the 18th Dynasty, a general of the army was made Pharaoh in hope that he would be able to save Egypt from being destroyed. His success brought about the 19th Dynasty. The 20th Dynasty saw some of the last great Pharaohs of Egypt. Ramesses II is known to have signed a mutual defense treaty with the Hittites, a powerful neighbor. This was a new landmark in diplomacy. Trade during this period brought new items and the exploitation of Kush made Egypt rich. From Kush came things like gold, ivory, ebony, cattle, gums, resins and semi-precious stones.” +\

Akhenaten’s “internal reforms caused ill feelings against those in powerful positions and allowed Egypt's foreign interests to be lost. Their ally during his reign, the Mitanni, were destroyed and their northern holdings captured by foreign powers. He was finally removed from the throne by those whom he had offended. The New Kingdom came to an end during the reign of Ramesses XI. Late in his reign civil war broke out and the viceroy of Kush was called upon to suppress Thebes. The viceroy was successful until the king's general Herihor drove the viceroy out of Thebes. The viceroy later came to rule Kush as an independent kingdom and it was forever lost to Egypt. +\

Great Dynasties of the New Kingdom

Around 1550 B.C., a ruler of the Theban 17th Dynasty, Kamose, led a series of military campaigns against the Hyksos king, Apophis. Under Kamose's brother Ahmose, the Hyksos were defeated and Egypt was reunited at the start of a new dynasty and a new kingdom. [Source: New Catholic Encyclopedia, The Gale Group Inc., 2003]

The 18th Dynasty marked the beginning of the New Kingdom. The Theban kings expelled the Hyksos and the Egyptian army expanded the borders of the kingdom into Palestine and Syria. The administration was reformed into a dynamic merit-based system for royal appointments. A powerful empire was created that ushered in new ideas and generated immense wealth for the pharaohs, [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Dr Aidan Dodson of the University of Bristol wrote: “Perhaps the height of Egyptian wealth and power came between 1550 and 1290 B.C. during the 18th Dynasty. The dynasty began with the expulsion of the Palestinian Hyksos rulers from the north of Egypt by King Ahmose I-an event that may have inspired the Biblical story of the Exodus. Carrying forward the momentum of this act, subsequent rulers, in particular Thutmose III, established an empire of client states in Syria-Palestine, and dominions stretching towards the heart of Africa. War booty and lively international trade founded on Egypt's highly productive gold mines made Egypt a major world player. [Source: Dr Aidan Dodson, Egyptologist, University of Bristol, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

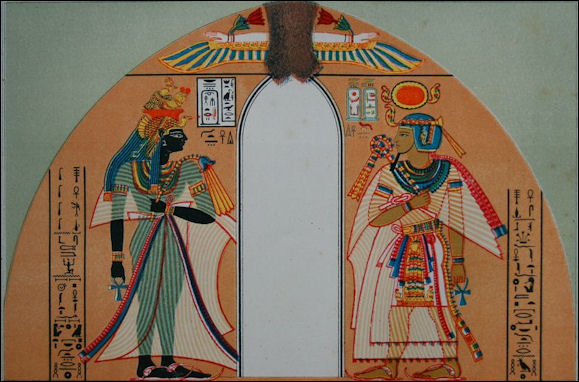

In the 19th Dynasty, after the upheavals of the late 18th Dynasty, the new royal house combined a return to traditional values with a number of innovations. Tradition is seen in the building of temples to the ancient gods and the repair of monuments damaged during the iconoclastic Akhenaten's reign, and also in an aggressive foreign policy. Under Ramesses II (1279-1212 B.C.), this culminated in the great battle against the Hittites at Qadesh in Syria. The long-term strategic stalemate that followed the battle, however, resulted in a peace treaty in 1258 that left the two powers the best of friends for the rest of the century. |::|

“Meanwhile, innovation was seen in the prominence granted to depictions of members of the royal family in public monuments, a practice that perhaps reached its peak at Abu Simbel, where the dominant figure in the smaller of the two temples seen here (on the right) was not the pharaoh, but Queen Nefertiry (not to be confused with the earlier Queen Nefertiti). However, the dynasty ended in chaos, with rebellion within the royal house, culminating in the end of the dynasty amid civil war.” |::|

See Separate Article: DYNASTIES 18-20 OF THE NEW KINGDOM OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

End of the New Kingdom

According to the Columbia Encyclopedia: “Egyptian civilization seems to have worn out rapidly after conflicts with the Hittites under the 19th dynasty and with sea raiders under the 20th dynasty. With a succession of weak kings, the Theban priesthood practically ruled the country and continued to maintain a sort of theocracy for 450 years. In the delta the Libyan element had been growing, and with the disappearance of the weak 21st dynasty, which had governed from Tanis, a Libyan dynasty came to power. This was succeeded by the alien rule of Nubians, black Africans who advanced from the south to the delta under Piankhi and later conquered the land. The rising power of Assyria threatened Egypt by absorbing the petty states of Syria and Palestine, and Assyrian kings had reached the borders of Egypt several times before Esar-Haddon actually invaded (673 B.C.) the land of the Nile. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

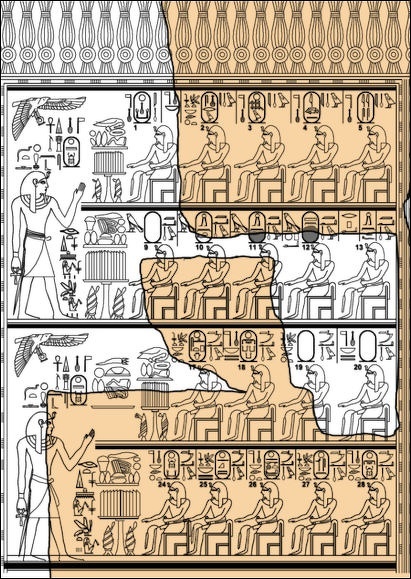

African products presented to the pharaoh

Toward the end of the Twentieth Dynasty, Egyptian power declined at home and abroad. Egypt was once more separated into its natural divisions of Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt. The pharaoh now ruled from his residence-city in the north, and Memphis remained the hallowed capital where the pharaoh was crowned and his jubilees celebrated. Upper Egypt was governed from Thebes. During the Twenty-first Dynasty, the pharaohs ruled from Tanis (San al Hajar al Qibliyah), while a virtually autonomous theocracy controlled Thebes. Egyptian control in Nubia and Ethiopia vanished. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

After Ramses III’s death Egypt began having economic problems and missed the boat with Iron Age — which began around 1200 B.C. and among other things made stronger and more powerful weapons possible — because it lacked sources of iron. Under a succession of weak leaders, Egypt fragmented and weakened. There were disputes between officials and governors and friction between the north and south. The priestly caste became so powerful it was able to take control of the government. But this occurred at a time when strong military was needed to fend off threats from Assyrians and Persians. Later Greeks and Romans would lay claim to the region. ^^^

Ramses III was the last great pharaoh, Ramses V died of small pox in 1151 B.C. Pockmarks are clearly visible on his unwrapped mummy. After the chaotic reign of Ramses XI (1115-1086 B.C. ) the long-unified Egyptian state broke apart. The burials at the Valley of the Kings ended abruptly following his death. After the death of Ramesses XI, the throne passed to Smendes, a northern relative of the High Priest of Amun. Smendes' reign (ca. 1070–1044 B.C.) initiated the Third Intermediate Period — a 350 year span, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art” of “politically divided rule and diffused power.”

Mycenaean-Egyptian Relations

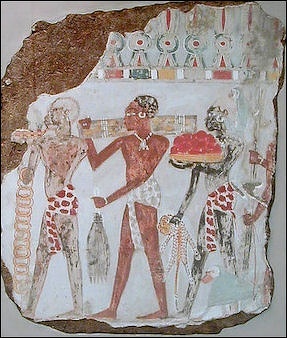

Stefan Pfeiffer of Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg wrote: “After the collapse of the Minoan culture, the Mycenaeans—who, like the Minoans, were located in “islands in the midst of the Great Green,” as the Egyptians called the Aegean—filled the economic gap left by Minoan traders. The earliest Egyptian attestation of the Mycenaeans dates to the 42nd year of Thutmose III’s reign. The transition from the Minoan to the Mycenaean culture may be reflected in Theban Tomb 100 (of the high official Rekhmira, who served at the end of Thutmose III’s reign and into that of Amenhotep II), in which an Aegean tribute carrier is depicted. The wall painting is a palimpsest: Originally, the depicted person was dressed in a typical Minoan loin-cloth; later on, this garment was modified to a multicolored kilt, which is generally attributed to Mycenaean origins. However, it is noteworthy that the interpretation of both garments as Minoan or Mycenaean, respectively, is nowadays questioned. [Source: Stefan Pfeiffer, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Mycenaean funeral mask

“Mycenaean cities are mentioned in the geographical lists of the House of Millions of years of Amenhotep III, proving knowledge of the Aegean world in Egypt. There were intense contacts in the time of Akhenaten, as is attested by Mycenaean pottery sherds dating to his reign. Mycenaean pottery is also found in post-Amarna times (for example, at Pi-Ramesse, the capital city built by Ramesses II): like their forefathers, Egyptian potters tried to copy the form and style of Minoan pottery, now aimed to imitate Mycenaean ware, even in faience or calcite (Egyptian alabaster).

“The view that post-Amarna contacts between the two worlds were mainly based on indirect trade relations via the Levant is nowadays being questioned; there are in fact hints to an exchange of individuals and ideas. What can be said is that the Mycenaeans, like the Minoans, were highly interested in Egyptian goods. Especially in Mycenae itself, many Egyptian objects bear witness to close trade relations. Moreover, Mycenae seems to have served as a “gateway community” for the import of Egyptian goods to the whole Aegean world.

“Summing up, it is not easy to determine the intensity of relations between the two cultures. It appears prudent to assume that in the Mycenaean Period (as well as in the Minoan) durations of close contacts alternated with those of merely sporadic contacts due to wars or natural catastrophes.”

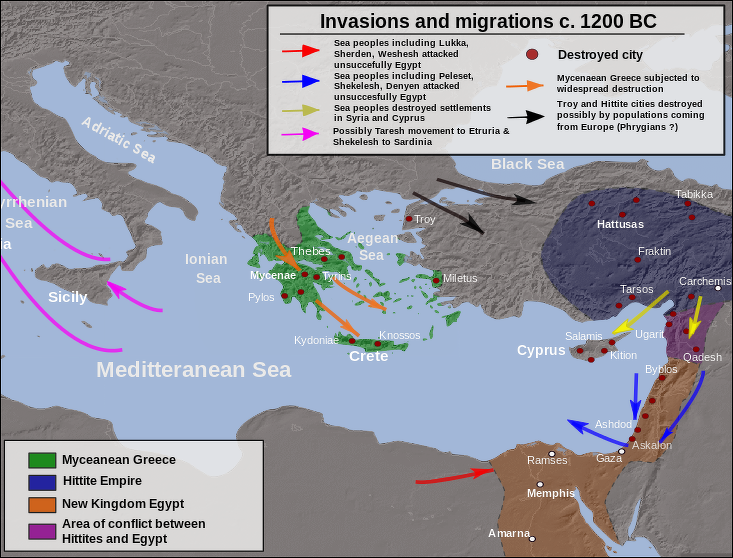

Late Bronze Age Collapse

Some historians the New Kingdom was brought factors that contributed to the Late Bronze Age, collapse, which refers to widespread societal and state collapse during the 12th century B.C. associated with mass migration, and the destruction of cities and believed to have been caused of exacerbated by environmental change. The collapse affected a large area of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Near East, particularly Egypt, eastern Libya, the Balkans, the Aegean, Anatolia, and, to a lesser degree, the Caucasus. It was sudden, violent, and culturally disruptive for many Bronze Age civilizations, and it brought a sharp economic decline to regional powers, notably ushering in the Greek Dark Ages. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Late Bronze Age collapse triggered the collapse of Mycenaean Greek civilization and the Hittite Empire of Anatolia and the Levant. The Middle Assyrian Empire in Mesopotamia and the New Kingdom of Egypt survived but were weakened, Other cultures such as the Phoenicians enjoyed increased autonomy and power with the decline of Egyptian, Hittite and Assyria military presence in West Asia.In what is commonly known as the “Late Bronze Age collapse,” the Hittite Empire and the civilization of the Mycenaean Greeks, as well as many smaller powers and the trade networks that linked them, fell apart. It also led to anarchy, uprisings, civil wars, and rival pharaohs in Egypt, while Assyria and Babylonia suffered famines, outbreaks of disease, and foreign invasions.

Tom Metcalfe wrote in National Geographic: Scholars have struggled for 200 years to explain the collapse as a consequence of volcanic eruptions or earthquakes; piracy, migrations, or invasions; political or economic failures; diseases, famines, or climate change; or even of the spread of iron metallurgy throughout a region dominated by bronze. The historian Eric Clein said in his book "1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed" (2014), the reasons for the collapse aren't understood, but they may include a wars, social upheaval, invasions or famines caused by climate changes or triggered by natural disasters. The theories with the most support argue that the shift to a drier and colder climate in the eastern Mediterranean disrupted food production, leading to shortages that exacerbated the cultural and economic problems already occurring in the region.

See Separate Article: LATE BRONZE AGE COLLAPSE africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024