Home | Category: Religion and Gods / Culture, Science, Animals and Nature

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GODS WITH BIRD HEADS

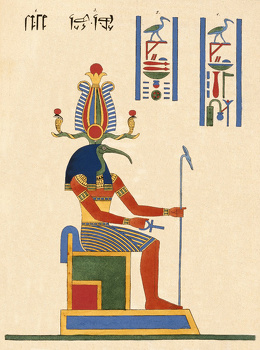

Horus was the falcon-headed sky god. He is the son of Osiris and Isis. Isis gave birth to Horus after Osiris was murdered and hid him from his wicked uncle Seth by concealing him under her magic hair. Horus was king of the living. He is often identified with protection and associated with pharaohs.

Thoth is the ibis-headed god of wisdom, knowledge, learning, writing, measurement, historical records, science, magic and scribes. He had a good memory and was involved in the after-life ceremony of the dead in which the heart was weighed against the feather of truth. Thoth is the lord of the moon and is sometimes represented as a baboon. Temples devoted to Thoth were often filled with caged ibises and other birds that were mummified after death.

There were entire cemeteries for ibises and falcons, associated with the gods Thoth and Horus. To meet the demand for falcons, which were hard to catch and raise in captivity, fake mummies made of bones wrapped in rags were sold. Half a million mummified birds have been found at a single location. At Tuna el-Gebel at Hermpolis a huge underground gallery filled with ibises and baboon contains animal mummies arranged in figure-eights, symbolic of the eight creative gods of Hermopolis.

See Separate Articles:

HORUS, THE FALCON-HEADED PATRON OF KINGS africame.factsanddetails.com

THOTH — THE IBIS-HEAD GOD OF WISDOM AND WRITING africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WILD ANIMALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SACRED ANIMALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: CULTS AND WORSHIP africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ANIMAL MUMMIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CROCODILES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MUMMIES, WORSHIP, TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BABOONS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Between Heaven and Earth: Birds in Ancient Egypt” by Rozenn Bailleul-LeSuer (2012) Amazon.com;

“Egypt - Ancient and Modern: History, Birds and Wildlife” (Birding Travelogues)

by Mark Dennis and Sandra Dennis (2022) Amazon.com;

“Beloved Beasts”by Salima Ikram (2006) Amazon.com;

“Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2015) Amazon.com;

“Soulful Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt” by Edward Bleiberg, Yekaterina Barbash , et al. (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptians and the Natural World: Flora, Fauna, and Science” by Prof. Dr. Salima Ikram, Jessica Kaiser, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt's Wildlife: An AUC Press Nature Foldout”

by Dominique Navarro and Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Wildlife: Past and Present” by Dominique Navarro (2016)

Amazon.com;

“A Guide to Extinct Animals of Ancient Egypt” by Anthony Romilio (2021) Amazon.com;

:A Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Egypt” by Sherif Bahaa El Din (2006) Amazon.com;

“A Field Guide to the Mammals of Egypt” by Richard Hoath (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Cat In Ancient Egypt” by Jaromir-Malek Amazon.com;

“Cats in Ancient Egypt: A Captivating Guide” (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

CT Scan of a Horus-Falcon- Mummy

There are many small mummies dedicated to Horus with a falcon or another bird inside. According to Egypt mythology, Horus was the falcon-headed son of Osiris and Isis; a deity associated with the sky and pharaohs. Marcia Javitt, a Clinical Professor of Radiology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, has taken CT scans of such mummies and studied them

On a roughly 25-centimeter (10-inch) -long cm) bird-shaped mummy, represented the god Horus, Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: Over time, the bird mummy had desiccated, meaning that the tissue got more dense, like beef jerky. Meanwhile, the marrow in the bones had dried out, leaving nothing but delicate bone tubes. So Javitt and her colleagues used a dual-energy CT, which uses both normal X-rays and less powerful X-rays, a technique that can reveal properties of the tissues that a regular CT scan can't, Javitt said. "In order to differentiate the soft tissues from one another and the bones and so on, it can be very helpful to use a dual-energy CT," Javitt said.[Source:Laura Geggel, Live Science, July 25, 2020]

Now, her team is identifying the bird's various tissues and bones. Javitt noted that the bird's neck is broken, but that this injury likely happened after the bird was dead. That's because the skin is broken too, and in most cases of broken bones, "you don't usually crack open the skin from one edge to the opposite side, you just break the bone," Javitt said. Moreover, the bird appears to be missing some of its abdominal organs, but more study is needed to determine which ones aren't there, she said. For instance, the heart appears to be present, as is the trachea.

In 2016, Archaeology magazine reported: “A mummified kestrel’s CT scan shows it choked on its last meal, probably because it had been force-fed. This bird of prey from Egypt, in the collection of Iziko Museums of South Africa in Cape Town, is one of millions of animals mummified as religious offerings, called votive mummies. Kestrels, which are common in Egypt, usually regurgitate the indigestible parts of their meals as pellets. The virtual autopsy of this bird shows that its stomach already contained digested remains from two mice and a sparrow, some of which it would have regurgitated before it consumed yet another mouse. The tail of that last meal got stuck in the gullet and choked the bird. Ancient Egyptians often force-fed their captive animals, which makes this the earliest known evidence of keeping and possibly breeding raptors. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2016]

1,700-Year-Old Egyptian Shrine with Decapitated Falcons

In October 2022, archaeology announced that they had found an ancient falcon shine in Berenike, an old Egyptian port city on the Red Sea, but weren't sure what to make of the decapitated falcons and unknown gods found there and a cryptic message that reads, "It is improper to boil a head in here." The shrine was described in a paper that was published in the American Journal of Archaeology. An iron harpoon that is about 13 inches (34 centimeters) long was found near the pedestal, researchers wrote in the study. "The decapitation of the falcons seems to be a local gesture of completing a live offering to the god of the shrine," David Frankfurter, a professor of religion at Boston University who was not involved in the excavation, told Live Science. "Votive sacrifice of a live animal usually involves some kind of killing or blood-asperging to show the commitment of the devotee." [Source Owen Jarus, Live Science, October 20, 2022]

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: In another room of the shrine, archaeologists found a stela, or pillar, with a Greek inscription that translates to "It is improper to boil a head in here." It remains a mystery why the falcons were decapitated, why a stela was placed in a room prohibiting the boiling of heads and why a harpoon was placed near the falcons. The stela depicts three deities: Harpokrates [also spelled Harpocrates] of Koptos, who is a "child god," and two enigmatic deities whose names are not clear. One has a "falcon head," and the other is a goddess who wears a crown made of "cow horns and a solar disk," the team wrote, noting that the god with the falcon head seems to be the most prominent of the three deities displayed.

One possible explanation is that the 15 headless falcons were offerings made to the deities, particularly the god with the falcon head. The harpoon also may have been an offering, the researchers proposed. "We hypothesize that the sacrificial animals were boiled before being presented to the god, perhaps to facilitate plucking their feathers, and that their heads were removed, according to the prescription on the stele," the team wrote in their paper.

The shrine also contained the remains of fish, mammals and bird eggshells. Some of these may have been offerings as well, and feasting may have happened at the shrine, the team noted. At the time the shrine was in use, around the fourth century A.D., the Roman Empire controlled Egypt but their control was waning. At Berenike, the team found inscriptions written by Blemmyan kings. The Blemmyes were semi-nomadic people who lived largely in what is now Sudan and parts of southern Egypt. The finds at Berenike suggest the Blemmyes lived at Berenike between the fourth and sixth centuries A.D., until they abandoned the site. The shrine shows that old religious practices persisted even after Christianity arose, Frankfurter told Live Science. At the time the shrine was in use, Christianity was the official religion of the Roman Empire.

Sacred Ibises

The ibis, with its narrow, curved beak and flashy white feathers and was the sacred bird of Thoth, the ancient Egyptian god of wisdom and writing. Bundled up ibises were the most common type of animal mummy in ancient Egypt. According to an ancient text, the Temple of Thoth in the necropolis of Saqqara at one time had 60,000 living ibises being readied for mummification, and archaeologists estimate that some four million ibis mummies were eventually buried there. A few mummies have been found with papyri petitioning the gods for help to resolve a family matter or cure an illness. The majority of animal mummies in the necropolis were not accompanied by written petitions and that it’s possible most were intended to carry oral messages. Perhaps pilgrims whispered their requests in the ears of the mummies, which then delivered their messages to the gods.

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: Beginning about 600 B.C., ibises were frequently mummified and given as sacrifices to the god. “Pilgrims would offer an ibis mummy to Thoth on his feast day either to ask for a wish to be granted or to thank him,” says archaeologist Sally Wasef of Griffith University. At the peak of this practice, upwards of 10,000 ibises were sacrificed every year, a number so large that some scholars have proposed that the birds must have been bred in centralized farms to meet the demand. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2020]

Although more than four million ibis mummies have been found at the site of Tuna el-Gebel, which lies on the Nile River about 170 miles south of Cairo, no massive ibis breeding facility has ever been located. This has raised the question of whether such installations actually existed. An international team of researchers recently conducted a study of genomes from 14 ibis mummies dating to 2,500 years ago, and found a surprising degree of genetic diversity. The ancient birds were nearly as diverse as the modern population, which inhabits most of Africa. The researchers suggest that the ibises sacrificed by ancient Egyptians were probably imported from across the continent.

Herodotus of Ibises and Phoenixes

Fifth Century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: On account of this deed it is (say the Arabians) that the ibis has come to be greatly honoured by the Egyptians, and the Egyptians also agree that it is for this reason that they honour these birds. The outward form of the ibis is this: — it is a deep black all over, and has legs like those of a crane and a very curved beak, and in size it is about equal to a rail: this is the appearance of the black kind which fight with the serpents, but of those which most crowd round men's feet (for there are two several kinds of ibises) the head is bare and also the whole of the throat, and it is white in feathering except the head and neck and the extremities of the wings and the rump (in all these parts of which I have spoken it is a deep black), while in legs and in the form of the head it resembles the other. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

There is also another sacred bird called the phoenix which I did not myself see except in painting, for in truth he comes to them very rarely, at intervals, as the people of Heliopolis say, of five hundred years; and these say that he comes regularly when his father dies; and if he be like the painting he is of this size and nature, that is to say, some of his feathers are of gold color and others red, and in outline and size he is as nearly as possible like an eagle.

This bird they say (but I cannot believe the story) contrives as follows: — setting forth from Arabia he conveys his father, they say, to the temple of the Sun (Helios) plastered up in myrrh, and buries him in the temple of the Sun; and he conveys him thus: — he forms first an egg of myrrh as large as he is able to carry, and then he makes trial of carrying it, and when he has made trial sufficiently, then he hollows out the egg and places his father within it and plasters over with other myrrh that part of the egg where he hollowed it out to put his father in, and when his father is laid in it, it proves (they say) to be of the same weight as it was; and after he has plastered it up, he conveys the whole to Egypt to the temple of the Sun. Thus they say that this bird does.

Northern Bald Ibis — The Akh Bird

northern bald ibis

Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “Three different kinds of ibis species are attested from ancient Egypt: the sacred ibis, the glossy ibis, and the northern bald ibis. Pictorial representations of the latter bird—easily recognizable by the shape of its body, the shorter legs, long curved beak, and the typical crest covering the back of the head—were used in writings of the noun akh and related words and notions (e.g., the blessed dead). We can deduce from modern observations that in ancient times this member of the ibis species used to dwell on rocky cliffs on the eastern bank of the Nile, that is, at the very place designated as the ideal rebirth and resurrection region (the akhet). Thus, the northern bald ibises might have been viewed as visitors and messengers from the other world—earthly manifestations of the blessed dead (the akhu). The material and pictorial evidence dealing with the northern bald ibis in ancient Egypt is accurate, precise, and elaborate in the early periods of Egyptian history (until the final phase of the third millennium B.C.). Later, the representations of this bird became schematized and do not correspond to nature. Thus, they do not present us with any direct and convincing evidence for the presence of the northern bald ibis in Egypt, and, moreover, they most probably witness both the bird’s decline and its disappearance from the country. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“As for the connection between the northern bald ibis and the akh, some scholars reached the conclusion that there was no (or only a phonetic) intrinsic relation between the two; others connected the root word akh with the term jakhu (“light, radiance or glow”) suggesting that the “glowing” purple and green feathers on the wings of the bird represented its link to the ideas of light, splendor, and brilliance. There are, however, scholars who have challenged the theory that the word akh was primarily connected with light and glare and suggested that the original meaning of the notions akh and akhu might have been linked, for example, to the idea of a mysterious, invisible force and to the efficacy of the sun at the horizon.

“Although there are many (probably secondary) aspects of the northern bald ibis’ nature that could have been important for the Egyptians such as, for example, the above- mentioned glittering colors on its wings, or its calling and greeting display, the main factor in holding the bird in particular esteem and connecting it with the akhu and the idea of resurrection was its habitat. This member of this ibis species used to dwell at the very place designated as the ideal rebirth and resurrection region (the eastern horizon as the akhet); moreover, its flocks might have very well represented the society of the “returning” dead. The ancient Egyptians saw migratory birds as the souls or spirits of the dead, and the fact that the northern bald ibis counts among the migratory birds might also have been very important. The arrival of these birds could have been a sign of the coming “spring” or the harvest season, as was the case at Bireçik. Thus, we find circumstantial evidence, which seems to support the theory that in ancient Egypt, the northern bald ibises were viewed as visitors and messengers from the other world and were earthly manifestations of the blessed dead.”

Characteristics of the Northern Bald Ibis

Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “The northern bald ibis is a middle-sized (height: 70 - 80 cm,weight: 1.3 kg, wingspan: 125 - 135 cm) gregarious bird that nests in colonies. These birds have a long curved red bill, red legs, and an unfeathered reddish head with the typical dark crest of neck plumes covering its back. The main color of the birds is black, with tints of blue, green, and copper. This iridescent purple and green “shoulder patch” on the wings of the bird is well visible in the sunlight. The northern bald ibises prefer to inhabit an arid or semi-arid environment, with cliffs for breeding and nesting. These birds feed during the day in adjacent dry fields and along rivers or streams by pecking on the ground. They live in areas with low level vegetation (arid, but preferably cultivated, places), where they can find worms, insects, lizards, and other small animals on which they feed. When the birds awake, or when they come together at sunset, this is always, but especially in the morning, marked by high activity. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The northern bald ibis has been found in North Africa and Ethiopia, the Middle East, and throughout Central Europe. However, only a few colonies survive in the world today, totaling in all not more than about 400 individuals. Some of them nest in the Souss Massa Park in Morocco , a few breed in Central Syria, and many northern bald ibises are kept in zoos or raised in special projects. The northern bald ibis still counts among the most critically endangered species and is on the Red List. Causes of the decline are thought to be pesticides, human persecution, habitat loss, and global fluctuation in rainfall.

“These ibises are usually migratory, they spend about four months in a breeding area, and their wintering period lasts between five and six months. The Syrian colony was observed to migrate through Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen to the central highlands of Ethiopia. On their return journey, they followed the western shore of the Red Sea through Eritrea to Sudan before crossing the Red Sea.

“In ancient Egypt, the northern bald ibises most probably nested on rocks and cliffs to the east of the Nile, as suggested both by Egyptian religious texts that connect the akhu with the eastern horizon (akhet) and modern observations made in Bireçik, Turkey and Morocco. It may, thus, be conjectured that every morning part of the colony flew to the Nile in search of food, descending on fields, settlements, or even cemeteries. In the evening, the birds probably would have flocked together and returned to the horizon.”

Images and Material Evidence of the Northern Bald Ibises

Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “The only material evidence for the presence of the northern bald ibis in Egypt in the form of skeletal remains comes from Maadi where the so-called Maadi culture (c. 4000 - 3400 B.C.) had its settlements. This unique find represents both the earliest evidence for this bird in Egypt and its only confirmed preserved bodily remains. The northern bald ibis was not hunted or sacrificed in Egypt, nor was it kept in temples and mummified at death. This fact stands in striking contrast to the sacred ibis and the glossy ibis that are known to have been kept and mummified ; there are many thousand mummified examples of the sacred ibis. Thus to date only pictorial representations of the northern bald ibis are recorded from later periods of Egyptian history. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

seated ibis from the 21st or 22nd dynasty

“The earliest Egyptian example of the bird’s depiction is probably attested on the so-called Ibis slate palette dated to the Naqada IIIa-b Period. Other examples of its early representation come from the Late Predynastic and Early Dynastic Periods. Depictions of the northern bald ibis among other birds and animals are preserved on two ivory objects from Hierakonpolis. It was suggested that northern bald ibises also appear on small bone labels from the tomb U-j at Abydos, either by itself or together with an image of (desert) mountains. Although these carvings on six ivory labels are still considered to depict the northern bald ibis, this identification is questionable since several of these representations seem more likely to correspond to the secretary bird (Sagittarius serpentarius). A schematic representation of northern bald ibises also occurs on small cylinder seals and other objects dated to the Early Dynastic Period. There are, however, even more attestations of the akh sign from the Early Dynastic Period in different styles and accuracy.

“From the Old Kingdom onwards, a pictorial representation of this bird was constantly used as a hieroglyphic sign for the word root akh; thus, it is often to be found in texts, especially in those that deal with the blessed dead (akhu). Detailed hieroglyphs of Old Kingdom tombs reveal how precise the observations were that the Egyptians made about this bird. In the Dynasty 5 mastaba of Hetepherakhti from Saqqara, depictions of the northern bald ibis are shown in several styles and even with the remains of polychrome showing the dark blue and red colors, which match with the living species. Similar artistic accuracy of the akh sign was reached in the case of the Dynasty 5 mastabas of Akhet- hotep at Saqqara, and Seshathotep at Giza. On the other hand, depictions of this ibis attested in later tombs, as for example, the Dynasty 12 tomb of Hesu-wer , are not as detailed as earlier examples. It is noteworthy that in the famous Beni Hassan tomb of Khnumhotep II dated to Dynasty 12, the northern bald ibis is represented in a surprisingly incorrect manner: neither the shape nor the colors (white body and red wings) match those of the living bird. Other birds and animals in this tomb, on the other hand, are represented with unique accuracy and detail.”

Northern Bald Ibis Cult Ritual

Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “From the time of the New Kingdom onwards, a still mysterious ritual (nowadays called Vogellauf) is attested among cultic scenes depicted on temple walls. Seventeen representations of the ritual are preserved from temples, three from private coffins. The oldest evidence for this ritual activity dates back to the time of Hatshepsut; the latest is attested in the Temple of Dendera and comes from the first century B.C.. The Vogellauf (bird run) ritual was probably associated with two other ritual “runs” known as the Ruderlauf (paddle run) and the Vasenlauf . [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The representations of the ritual show the king running towards a deity with a northern bald ibis in his left hand and three rods or scepters of life, stability, and power in the right one. Among the recipients we mainly find female deities (Hathor, Bastet, Satet, Isis, or Weret-hekau) or the creator god (Amun or Ra-Harakhte). Unfortunately, the accompanying text does not specify the cultic activity that is being performed by the king: “running (or hurrying) to deity X so that he (the king) might perform the life-giving (ceremony?) forever.” The deity is also greeting the king (his/her son) in return and guaranteeing him his/her joy and favor.

“However, due to artistic inaccuracies and iconographical differences, it can be assumed that the Vogellauf ritual did not embrace any sacrifice of the bird. “Moreover, during the New Kingdom there were most probably no northern bald ibises at the king’s disposal. It is thus more likely that the northern bald ibis in the king’s hand is to be read symbolically. It either stood for the hieroglyph akh and referred to concepts linked to this word, or it represented a bird that was not present at the ritual (as a reminder or a representative: “hasting to the god with the first swallow”).”

Saddle-Billed Stork — the Ba-Bird

saddle-billed stork

Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “The ba (bA) is undoubtedly among the most important ancient Egyptian religious notions,although it usually lacks an accurate translation. All interpretations and verbal images that are commonly used to describe the concept of the ba (i.e., as the “soul”) should be considered incomplete, since the original notion encompassed several different but interconnected aspects, spanning from the divine to the manifestation (eidolon) of the divine, and from the super-human manifestation of the dead to the notion of the soul (psyche) or reputation. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

“The term ba and its hieroglyphic renderings are attested for all periods of ancient Egyptian history, from the beginnings of the Egyptian writing system until the very dusk of the hieroglyphic script. Over the course of time, the word ba was written variously with signs representing a stork, a ram, a human-headed falcon, and, in the Pyramid Texts, a leopard’s head. It remains, however, disputable whether the ba of this spell has the same meaning as it does in other contexts. The stork of the G 29-sign represents both the earliest and the most attested depiction connected to the religious concept of the ba. Fortunately, this ba-sign can easily be recognized as the saddle-billed stork, Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis, since it usually shows the bird’s most characteristic features: long legs, long neck, a strong and sharp bill, and most importantly, the presence of a wattle (under the bill) or a lappet (at its chest). This bird should not be mistaken for the (American) jabiru (Jabiru mycteria)—an error made by Gardiner in his Grammar

The saddle-billed stork is a tall and majestic bird that can grow to a height of 150 cm, attaining a wingspan of up to 270 cm. White and black dominate its striking coloration. Its wings are mainly black, tipped with white feathers. The head and neck are completely black and feature a large, pointed bill, which is mainly red with a black band. A yellow frontal shield (called the “saddle”) at the upper end of the bill represents one of the most characteristic features of this bird. At the base of the lower mandible, where it meets the neck, the saddle-billed stork has the diagnostic small yellow wattle. All these characteristics (together with its specific posture and long legs) are usually present in its ancient Egyptian representations, and thus the saddle-billed stork can usually be easily recognized among other bird-signs. The bird is, however, depicted with varying accuracy in different historical periods. These non- migratory birds prefer to breed in marshes and water-lands, where they feed on fish, frogs, small reptiles, or even small birds. Nowadays, the saddle-billed stork is a permanent resident in sub-Saharan Africa; there have been no attested observations of this bird in present- day Egypt.

“The impressive size and stately appearance of the saddle-billed stork, which was probably the largest flying bird of ancient Egypt, might have largely influenced its significance to the Egyptians. These characteristics might also have played a key role in connecting this particular bird with the ba-concept, since it seems only logical that such an impressive bird should represent an earthly manifestation of divine (i.e., heavenly) powers.”

Images of the Saddle-Billed Stork

ba bird

Jírí Janák of Charles University in Prague wrote: “The earliest depictions of the saddle-billed stork in Egypt are attested on several knife and mace handles dated to the Late Predynastic Period. These images were rendered with great accuracy and they probably represent the earliest pictorial representations of the saddle- billed stork in human history. The best depiction is preserved on the so-called Carnarvon knife handle made of ivory. On it a row of these birds can be observed together with two parallel rows of powerful wild animals (elephants, bulls, and lions). The first row or register encompasses eight saddle-billed storks with a giraffe between the first and second stork. A similar scene can be observed on earlier objects, such as the Davis comb, where images of elephants, lions, bulls, hyenas or dogs, and antelopes or gazelles were engraved in five parallel registers, both on the front and the rear of the comb. On both sides, there is a row of five birds with a giraffe in between the first and the second bird. Four birds can doubtlessly be identified as saddle- billed storks, according to the presence of the above-mentioned characteristic features (the saddle, wattle, etc.). The last bird in both rows can only be described as a tall, long-legged bird with a strong bill (the yellow-billed stork?), since both the wattle and the saddle are missing. [Source: Jírí Janák, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2014, escholarship.org ]

“The handle of the so-called Brooklyn knife also bears several registers of animals, including elephants, lions, bulls, jackals, dogs, rams, and birds. The birds (mainly saddle-billed storks, identified by their main features) are depicted in the second register. As in the two above- mentioned cases, a giraffe occurs after the first stork. These storks also occur within a row of tall birds (below a row of elephants and above lions) on the Pitt-Rivers knife handle. A similar pattern appears on a mace handle from Sayala in Lower Nubia. This handle, dated to the Middle to Late A-Group, was embossed with the shapes of several wild animals. At the top, we can see an elephant, a giraffe, and a large stork. Identification of the latter bird is, however, doubtful, since it was depicted with neither a wattle nor saddle. On the other hand, other features (posture, huge bill, long neck, etc.) and the context would suggest that this image represents a depiction of the saddle-billed stork.

“The early representations of the saddle- billed stork among powerful animals in all the above-mentioned cases can by no means be regarded as coincidental. They suggest that this impressive bird made a significant impact on the mindset of the Egyptians, who consequently associated it with the idea of greatness and power. Moreover, we can assume that this association with power, greatness, and awe formed the basis of the relationship between the Egyptians’ concept of the ba as the earthly manifestation of heavenly (i.e., divine and otherwise unseen) power and its hieroglyphic representation.

“Early representations of the saddle-billed stork are also present on several of the famous bone labels from Tomb U-j at Abydos, where the bird can be recognized by its size, robust bill, and often by the “saddle” at the bill’s upper end. As for the Early Dynastic Period, saddle-billed stork depictions occur on several seals, and an accurate, though fragmentary, representation of this bird is attested on a fragment of a large porphyry jar from Hierakopolis. Fine images of the saddle-billed stork can also be encountered among hieroglyphs from the 3rd-Dynasty tomb of Khabausokar in Saqqara. In the latter case, however, the representations tend to be schematized: the upper wattle is in its standard place, but the bill is shortened, as it is in later periods. In the pyramid complex of the 4th- Dynasty king Sahura, the execution of the ba- sign remains similar to the ba-hieroglyph in Khabausokar’s tomb, though the position of the wattle differs slightly. An analogous depiction of this bird occurs on a slab stela from the tomb of Wepemnofret in Giza that was currently re- dated to the early phase of the 4th Dynasty. Representations of the saddle-billed stork become even more schematized during later phases of the Old Kingdom: its size and posture resemble those of a duck or goose rather than of a tall stork, its bill and neck are much shorter than on earlier representations, and the black (sic!) wattle “moves” from the base of the bill to the neck of the bird, and sometimes even to its chest.

“As for the artistic and hieroglyphic depictions of the saddle-billed stork, two facts are of particular importance. First, the best and the most elaborate depictions of the saddle- billed stork come from the earliest periods of Egyptian history. During the second phase of the Old Kingdom, the sign became schematized with the above-mentioned inaccuracies. From this period onwards, the schematized ba-sign remained almost unchanged. Second, there are no skeletal or other remains of the saddle-billed stork (e.g., mummified specimens) attested for any period of Egyptian history. Moreover, no artistic representations of this bird are present in any scene where other birds usually occur. These facts have led scholars to the conclusion that the bird disappeared from Egypt during the first half of the Old Kingdom, or its distribution area shrank to sub-Saharan regions, as happened to other animal species, such as the giraffe. This opinion can be supported by the lack of material, textual, and pictorial evidence for the presence of the saddle-billed stork in Egypt at least from the second half of the Old Kingdom and also by artistic and scribal inaccuracies in the writing of the ba-sign.

“In this context, it is especially significant that the earliest attestation of the notion of the ba in association with a non-royal person comes from the final phase of the Old Kingdom. According to some scholars, the concept of the ba had changed after the collapse of the Old Kingdom , in keeping with the often discussed and still questionable phenomenon of the “democratization of the afterlife”. Although the “democratization” theory has not been fully accepted and may even be abandoned in future, it is noteworthy that the shift in the characterization of the ba from “the manifestation of the divine” to the more general “manifestation of any super-human entity” occurred at the very end of the Old Kingdom and during the First Intermediate Period. This was the time when the original link between the notion/sign and its earthly model (the bird itself) got lost after centuries of the model’s absence and of the sign’s degradation and schematization. The new understanding and interpretation of the ba- notion subsequently found its expression in a new hieroglyph in the time of the Middle Kingdom. The iconographical value of this later sign stressed the new characteristics of the ba-notion (e.g., afterlife manifestation of the deceased, free movement, “migration” of the soul), which differed from the original aspects of greatness and power.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024