Home | Category: Culture, Science, Animals and Nature

WILD ANIMALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

hippo relief

In Pharonic times, the Nile was home to hippos and crocodiles. Many of the animals that we associate with the Serengeti Plains of Tanzania and Kenya like antelopes, hyenas, lions, cheetahs and jackals were found in Egypt and Mesopotamia 4000 years ago. Until maybe a hundred years ago leopards, cheetahs, oyrx, aardwolves, striped hyenas and caracals could be found in the mountains and deserts. An ancient Egyptian papyrus describes dozens of venomous snakes, including rare 4-fanged serpent.

Robert Partridge of the BBC wrote: “Animals of all kinds were important to the Ancient Egyptians, and featured in the daily secular and religious lives of farmers, craftsmen, priests and rulers. The great cats of Africa were highly regarded by the Ancient Egyptians, and the king was often referred to as being as brave and fearless as a lion. Great cats were hunted, and their skins were greatly prized, but they were not always killed and the smaller cats, such as the cheetah, were often tamed and kept as pets. A gilded figure of a cheetah, with the distinctive 'tear' mark, was found on one of Tutankhamun's funerary beds. “ [Source: Robert Partridge, BBC, February 17, 2011]

“Jackals were often seen in the deserts close to the towns and villages, scavenging whatever food they could from their human neighbours. They were also often found in cemeteries, and for this reason jackals became associated with the dead-as represented by the god Anubis. This god was worshipped both as the guardian of cemeteries and as the god who presided over the embalming of the dead.” An image of a jackal made of carved wood was found in the tomb of Tutankhamun. Dog-faced hamadryas baboons were considered sacred but were not native to Egypt. They were mummified and portrayed in images in temples and monoliths. Sacred ones were kept at temples and enshrined in death at catacombs, where priest prayed and made offerings to them.

Many animals were associated with religion and magic and divinity. Ibises, jackals, lions and many other animals were associated with specific gods and were worshipped as divinities. Hippos were warriors against Seth, the god of evil. Hedgehogs possessed magical powers in the grave. The ancient Egyptians used to wear hedgehog amulets to ward off snakebites. Hedgehogs have a resistance but are not immune to snake venom. Snakes were widely worshiped and associated with the Nile River and fertility. Cobras were symbols of divine rule and were prominently featured on the head dresses of the Pharaohs. Lotus flowers are featured in ancient Egyptian art. They are now found in the Nile Delta. The papyrus reed is fairly uncommon now. It has been largely displaced by other kinds of grasses.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SACRED ANIMALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: CULTS AND WORSHIP africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ANIMAL MUMMIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SACRED BIRDS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: IBISES, FALCONS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BABOONS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Ancient Egyptians and the Natural World: Flora, Fauna, and Science” by Prof. Dr. Salima Ikram, Jessica Kaiser, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt's Wildlife: An AUC Press Nature Foldout”

by Dominique Navarro and Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Wildlife: Past and Present” by Dominique Navarro (2016)

Amazon.com;

“A Guide to Extinct Animals of Ancient Egypt” by Anthony Romilio (2021) Amazon.com;

:A Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Egypt” by Sherif Bahaa El Din (2006) Amazon.com;

“A Field Guide to the Mammals of Egypt” by Richard Hoath (2009) Amazon.com;

“Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2015) Amazon.com;

“Soulful Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt” by Edward Bleiberg, Yekaterina Barbash , et al. (2013) Amazon.com;

“Beloved Beasts”by Salima Ikram (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Cat In Ancient Egypt” by Jaromir-Malek Amazon.com;

“Cats in Ancient Egypt: A Captivating Guide” (2025) Amazon.com;

“Between Heaven and Earth: Birds in Ancient Egypt” by Rozenn Bailleul-LeSuer (2012) Amazon.com;

“Egypt - Ancient and Modern: History, Birds and Wildlife” (Birding Travelogues)

by Mark Dennis and Sandra Dennis (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

Herodotus on the Fens (Marshes) of Ancient Egypt

Fens are peat-forming wetlands that rely on groundwater input and require thousands of years to develop and cannot easily be restored once destroyed. Fens are also hotspots of biodiversity. They often are home to rare plants, insects, and small mammals.

Fifth Century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: All these are customs practised by the Egyptians who dwell above the fens: and those who are settled in the fenland have the same customs for the most part as the other Egyptians, both in other matters and also in that they live each with one wife only, as do the Greeks; but for economy in respect of food they have invented these things besides: — when the river has become full and the plains have been flooded, there grow in the water great numbers of lilies, which the Egyptians call lotus; these they cut with a sickle and dry in the sun, and then they pound that which grows in the middle of the lotus and which is like the head of a poppy, and they make of it loaves baked with fire. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

The root also of this lotus is edible and has a rather sweet taste: it is round in shape and about the size of an apple. There are other lilies too, in flower resembling roses, which also grow in the river, and from them the fruit is produced in a separate vessel springing from the root by the side of the plant itself, and very nearly resembles a wasp's comb: in this there grow edible seeds in great numbers of the size of an olive-stone, and they are eaten either fresh or dried. Besides this they pull up from the fens the papyrus which grows every year, and the upper parts of it they cut off and turn to other uses, but that which is left below for about a cubit in length they eat or sell: and those who desire to have the papyrus at its very best bake it in an oven heated red-hot, and then eat it. Some too of these people live on fish alone, which they dry in the sun after having caught them and taken out the entrails, and then when they are dry, they use them for food.

Crocodiles in Ancient Egypt

crocodile sculpture

The Egyptians revered crocodiles. Their river god Sobek is modeled after one. Entire crocodiles families were mummified and placed in sacred tombs with gold bracelets placed on their ankles. A Greek historian visiting an Egyptian Crocodileopolis saw priests feed them honey wine and cakes.

Robert Partridge of the BBC wrote: “Crocodiles were a real danger to the Egyptians and, like other dangerous animals, were given divine status in the hope that in return they would not attack humans. The Nile crocodile can grow to six metres in length, and there are many tales of Ancient Egyptians being killed by them. Crocodiles are no longer found in Egypt. [Source: Robert Partridge, BBC, February 17, 2011]

The crocodile was regarded as the ruler of the water, and it was believed that the water-god Sobek assumed his shape. Pictures of the time of the Old Kingdom represent them frequently — the crocodile lying in wait for the cows when they should come into the water The crocodile was hunted, in spite of its sanctity as being sacred to the water god; and that there are no representations of this sport is owing probably to the fact that they had scruples of conscience about it. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

RELATED ARTICLE: CROCODILES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MUMMIES, WORSHIP, TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com

Hippos in Ancient Egypt

In Pharonic times, the Nile was home to hippos as well as crocodiles. Hippos were considered pests because they ruined crops. Robert Partridge of the BBC wrote: “The hippopotamus was a danger to boats on the river Nile, and to people working on or near the river banks. These animals were represented by the goddess Tauret, and offerings were made to her in the hope of placating her. She was also a goddess of fertility, represented as a pregnant hippopotamus. Many models of hippopotami were made of blue Egyptian faience, their bodies decorated with representations of the river plants that grew where the animals lived. [Source: Robert Partridge, BBC, February 17, 2011]

The marshes of the Nile and the Nile Delta were home to crocodiles and hippos as well as birds and fish that were important sources of meat. The hippopotamus especially, with its furious roar, and his "extremely pugnacious, restless nature" ' was accounted the embodiment of all that was rough and wild. Old Kingdom pictures show show the hippopotamus attacking the rudder of a boat, or even seizing a crocodile. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Ancient Egyptians greatly feared hippos, viewing them as dangerous and aggressive animals, especially when provoked, according to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. These mostly herbivorous mammals were regarded as having insatiable appetites. They wreaked such havoc on farmers' fields one papyrus refers to a particularly bad harvest in which "the worm took half and the hippopotamus ate the rest. " Ancient Egyptians feared hippos, to the point that they removed three of the statuette's legs so it wouldn't cause chaos in the afterlife. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, July 5, 2024]

Hippopotamus Hunting in Ancient Egypt

Hippo hunts were a common sport among the ancient Egyptians, who would use harpoons to snare the large beasts, which were associated with chaos. By 3000 B.C., depictions of kings successfully battling hippos became commonplace, as it was a way to show rulers overcoming chaos. However, due to overhunting, the last wild hippos disappeared from Egypt by the early 19th century, according to The Met. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, July 5, 2024]

Unlike with the crocodile, there were few religious scruples about the hippopotamus, and men of rank of all times liked to have representations of hippopotamus-hunting in their tombs, the more so because the spice of danger made them proud of their success. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Ancient Egyptians seem to have pursued the hippopotamus only on the water from their boats; a harpoon served as weapon, the shaft of which freed itself from the point as soon as the animal was hit. If the wounded animal dashed down into deep water, the hunter allowed him to do so, by letting out the line attached to the harpoon, though there was danger of the boat being carried under. The hippopotamus was soon obliged to rise to the surface to breathe, and then the sportsman could wound him again. Gradually, as in whaling, the powerful animal was exhausted by frequent attacks, and finally a rope was thrown over his great head and the creature was dragged to land.

Hippopotamus-hunting is often represented in the Theban tombs, the pictures are unfortunately generally disturbed. Fully described, the harpoon of the Old Kingdom does not seem to have been so complicated as the one there described of the New Kingdom It is doubtful, according to Wilkinson's figure, whether it was a lasso which was thrown over the animal’s head. It might be a net like that still used in Africa to throw over the heads of wild boar.

Insects, Frogs and Snakes in Ancient Egypt

grasshopper

Robert Partridge of the BBC wrote: “The small scarab or dung-beetle collects animal dung, rolls it into a ball, then lays its eggs in this ball. The Egyptians imagined a huge scarab beetle rolling the ball of the sun across the sky, which led to an association of the beetle with the sun god Ra. A representation of a scarab beetle can often be seen on amulets made to protect the wearer against evil. The Egyptian name for the scarab was Kheper, and it appears in many royal names, such as the Cartouche of King Kheperkare, Senuseret I. [Source: Robert Partridge, BBC, February 17, 2011]

“The banks of the river Nile provided a rich area for smaller forms of wildlife such as amphibians and insects. Frogs could be a particular nuisance if there were too many of them, but they served the useful purpose of keeping the insect population in check. Many tomb reliefs depicting activities such as fishing are brought to life by the addition of images of frogs and dragonflies. The images are remarkable for the attention to detail of the artists who created them. |::|

“The Ancient Egyptians were very wary of snakes, especially the poisonous Egyptian cobra and the black-necked spitting cobra, which could spit venom into the eyes of an aggressor. The cobra was adopted as protector of the king, and representations of the snake (referred to by Egyptologists as an uraeus), with its hood raised and ready to spit venom, sometimes adorn the brows of various kings. One example of solid gold inlaid with coloured stones, belonged to King Senuseret I. |::|

Cobras were an important symbol of the ancient Egyptians. A cobra was on the headdress of the pharaoh and appears often in art and religious imagery. Egyptian cobras were represented in Egyptian mythology by the cobra-headed goddess Meretseger. A stylised Egyptian cobra — in the form of the “uraeus” representing the goddess Wadjet — was the symbol of sovereignty for the Pharaohs.

See Egyptian cobras under VENOMOUS SNAKES IN THE MIDDLE EAST africame.factsanddetails.com ; See scarabs Under ANCIENT EGYPTIAN SYMBOLS africame.factsanddetails.com

Pets and Wild Animals in Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians kept pets. Pet cats date back to ancient Egypt. Dogs go back thousands of years before that. The Egyptians may have succeeded in domesticating cranes, ibex, gazelles, oryx and baboons. Bas reliefs show men trying to tame hyenas by tying them up and force feeding them meat.

Robert Partridge of the BBC wrote: “'Man's best friend' was considered not just as a family pet, but was also used for hunting, or for guard duty, from the earliest periods of Egyptian history. Pet dogs were well looked after, given names such as 'Blackey' or 'Brave One', and often provided with elaborate leather collars. The mummy of a dog, probably a royal pet; was found in a royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings. [Source: Robert Partridge, BBC, February 17, 2011]

“Cats were kept to protect food stores from rats, mice and snakes, and were kept as pets. They are shown in paintings beneath their owners' chairs, or on their laps. Egyptian cats resembled modern tabby cats. The Egyptian name for cat is 'miw'. Cats also had a symbolic or religious meaning, as represented by the goddess Bastet, and in later periods of Egyptian history cat mummies were used as offerings to the gods.” |::|

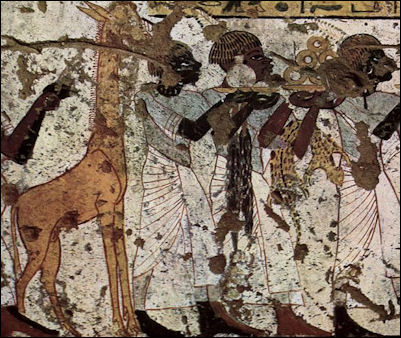

The Egyptians were fond of cheetahs and kept herds of gazelles and antelopes. Oryxes and other kinds of antelope were kept as household pets. Even though the Egyptians may have tamed elephants there is no evidence they were domesticated like elephants in ancient Carthage.

Elephants in elaborate tombs were found in cemetery in Hierakonpolis, dated to 3500 B.C. One of the elephants was ten to eleven years old. That is the age when young males are expelled from the herd. Modern animals trainers say elephants at that age are young and inexperienced and can be captured and trained.

See Separate Article: PETS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: CATS, DOGS, WILD ANIMALS africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Animal Mummies

pet cheetah in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians not only mummified their rulers, they also made mummies of baboons, ibises, cats, dogs, rabbits, Nile perch, bulls, vultures, elephants, donkeys, lizards, shrews, scarab beetles, horses, gazelles, crocodiles, snakes, catfish, ducks and falcons. They were often elaborately wrapped in bandages printed with magical spells and carefully painted. John Taylor of the British Museum told AP, "The Egyptians mummified almost everything that moved, as they were considered representative of gods and goddesses."

The animal mummies were usually carefully wrapped and placed in a coffin or jar. Sometimes the animal mummies were placed in small limestone coffins. Some coffins were topped by golden shrews. Shrews were symbols of the sun’s renewal. They were sometimes given as offerings. Research has show that the animals were often prepared and embalmed with the same care as humans.

Millions of mummified animals have been found. It was long thought that animals were simply wrapped in coarse linen rags and immersed in preservative. Research by Richard Evershed, an expert on archaeological chemistry at the University of Bristol, found the same materials — including fine linen, beeswax, cedar resins, bitumen and pistacia — used in human mummies were also used in mummies of cats, ibises and hawks dated to between 9th and 4th centuries B.C.

Today animal mummies are among the most popular exhibits in the treasure-filled Egyptian Museum. A.R. Williams wrote in National Geographic, “Visitors of all ages, Egyptians and foreigners, press shoulder to shoulder to get a look. Behind glass panels lie cats wrapped in strips of linen that form diamonds, stripes, squares and crisscrosses. Shrews in boxes of carved limestone, rams covered with gilded and beaded casings. A gazelle wrapped in a tattered matt of papyrus...A 17-foot, knobby-backed crocodile, buried with baby croc mummies in its mouth. Ibises in bundles with intricate appliques. Hawks. Fish. Even tiny scarab beetles and the dung balls they ate. [Source: A.R. Williams, National Geographic, November 2009]

The oldest-known animal mummies, dated to 2950 B.C., are dogs, lions and donkeys buried with kings in the 1st dynasty in their funeral complexes at Abydos, Symbols of the god Troth, ibises were mummified in greater numbers than any other animal.

See Animal Mummies

Herodotus on Hippos, Ibises and Winged Snakes

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”:Hippopotamuses are sacred in the district of Papremis, but not elsewhere in Egypt. They present the following appearance: four-footed, with cloven hooves like cattle; blunt-nosed; with a horse's mane, visible tusks, a horse's tail and voice; big as the biggest bull. Their hide is so thick that, when it is dried, spearshafts are made of it. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“Near Thebes there are sacred snakes, harmless to men, small in size, and bearing two horns on the top of their heads. These, when they die, are buried in the temple of Zeus, to whom they are said to be sacred. There is a place in Arabia not far from the town of Buto where I went to learn about the winged serpents. When I arrived there, I saw innumerable bones and backbones of serpents: many heaps of backbones, great and small and even smaller. This place, where the backbones lay scattered, is where a narrow mountain pass opens into a great plain, which adjoins the plain of Egypt. Winged serpents are said to fly from Arabia at the beginning of spring, making for Egypt; but the ibis birds encounter the invaders in this pass and kill them. The Arabians say that the ibis is greatly honored by the Egyptians for this service, and the Egyptians give the same reason for honoring these birds. 76.

“Now this is the appearance of the ibis. It is all quite black, with the legs of a crane, and a beak sharply hooked, and is as big as a landrail. Such is the appearance of the ibis which fights with the serpents. Those that most associate with men (for there are two kinds of ibis36 ) have the whole head and neck bare of feathers; their plumage is white, except the head and neck and wingtips and tail (these being quite black); the legs and beak of the bird are like those of the other ibis. The serpents are like water-snakes. Their wings are not feathered but very like the wings of a bat.

hippos and crocodiles from the mastaba of Princess Idut

Herodotus and Strabo on Animals in Libya and Mauritania

Herodotus wrote in Book IV.42-43 The Histories (c. 430 B.C.): . For the eastern side of Libya, where the wanderers dwell, is low and sandy, as far as the river Triton; but westward of that the land of the husbandmen is very hilly, and abounds with forests and wild beasts. For this is the tract in which the huge serpents are found, and the lions, the elephants, the bears, the aspics, and the horned asses. Here too are the dog-faced creatures, and the creatures without heads, whom the Libyans declare to have their eyes in their breasts; and also the wild men, and wild women, and many other far less fabulous beasts.[Source: Herodotus, “The History,” trans. George Rawlinson (New York: Dutton & Co., 1862]

“Among the wanderers are none of these, but quite other animals; as antelopes, gazelles, buffaloes, and asses, not of the horned sort, but of a kind which does not need to drink; also oryxes, whose horns are used for the curved sides of citherns, and whose size is about that of the ox; foxes, hyaenas porcupines, wild rams, dictyes, jackals, panthers, boryes, land-crocodiles about three cubits in length, very like lizards, ostriches, and little snakes, each with a single horn. All these animals are found here, and likewise those belonging to other countries, except the stag and the wild boar; but neither stag nor wild-boar are found in any part of Libya. There are, however, three sorts of mice in these parts; the first are called two-footed; the next, zegeries, which is a Libyan word meaning "hills"; and the third, urchins. Weasels also are found in the Silphium region, much like the Tartessian. So many, therefore, are the animals belonging to the land of the wandering Libyans, in so far at least as my researches have been able to reach.

Strabo wrote in “Geography,” XVII.iii.1-11 (A.D. c. 22): “Writers in general are agreed that Mauretania is a fertile country, except a small part which is desert, and is supplied with water by rivers and lakes. It has forests of trees of vast size, and the soil produces everything. It is this country which furnishes the Romans with tables formed of one piece of wood, of the largest dimensions, and most beautifully variegated. The rivers are said to contain crocodiles and other kinds of animals similar to those in the Nile. Some suppose that even the sources of the Nile are near the extremities of Mauretania. In a certain river leeches are bred seven cubits in length, with gills, pierced through with holes, through which they respire. This country is also said to produce a vine, the girth of which two men can scarcely compass, and bearing bunches of grapes of about a cubit in size. All plants and pot-herbs are tall, as the arum and dracontium [snake-weed]; the stalks of the staphylinus [parsnip?], the hippomarathum [fennel], and the scolymus [artichoke] are twelve cubits in height, and four palms in thickness. The country is the fruitful nurse of large serpents, elephants, antelopes, buffaloes, and similar animals; of lions also and panthers. It produces weasels (jerboas?) equal in size and similar to cats, except that their noses are more prominent, and multitudes of apes, of which Poseidonius relates that when he was sailing from Gades to Italy, and approached the coast of Africa, he saw a forest low upon the sea-shore full of these animals, some on the trees, others on the ground, and some giving suck to their young. He was amused also with seeing some with large dugs, some bald, others with ruptures and exhibiting to view various effects of disease.”[Source: Strabo, “The Geography of Strabo” translated by H. C. Hamilton, esq., & W. Falconer (London: H. G. Bohn, 1854-1857), pp. 279-284]

Strabo on Animals in the Horn of Africa

Elephant in Libyan cave art

Strabo wrote in “Geography” (A.D. 22): “It produces also leopards of great strength and courage, and the rhinoceros. The rhinoceros is little inferior to the elephant; not, according to Artemidorus, in length to the crest, although he says he had seen one at Alexandria, but it is somewhat about a span less in height, judging at least from the one I saw. Nor is the color the pale yellow of boxwood, but like that of the elephant. It was of the size of a bull. Its shape approached very nearly to that of the wild boar, and particularly the forehead; except the front, which is furnished with a hooked horn, harder than any bone. It uses it as a weapon, like the wild boar its tusks. It has also two hard welts, like folds of serpents, encircling the body from the chin to the belly, one on the withers, the other on the loins. This description is taken from one I myself saw. Artemidorus adds to his account of this animal, that it is peculiarly inclined to dispute with the elephant for the place of pasture; thrusting its forehead under the belly of the elephant, and ripping it up, unless prevented by the trunk and tusks of his adversary. [Source: Strabo, “The Geography of Strabo:” XVI.iv.4-17; XVII.i.53-54, ii.1-3, iii.1-11, translated by H. C. Hamilton, esq., & W. Falconer (London: H. G. Bohn, 1854-1857), pp. 191-203, 266-272, 275-284]

“Camel-leopards are bred in these parts, but they do not in any respect resemble leopards, for their variegated skin is more like the streaked and spotted skin of fallow deer. The hinder quarters are so very much lower than the fore quarter that it seems as if the animal sat upon its rump, which is the height of an ox; the fore legs are as long as those of the camel. The neck rises high and straight up, but the head greatly exceeds in height that of the camel. From this want of proportion, the speed of the animal is not so great, I think as it is described by Artemidorus, according to whom it is not to be surpassed. It is not however a wild animal, but rather like a domesticated beast; for it shows no signs of savage disposition.

“This country, continues Artemidorus, produces also sphinxes, cynocephali, and cebi, which have the face of a lion, and the rest of the body like that of a panther; they are as large as deer. There are wild bulls also, which are carnivorous, and greatly exceed ours in size and swiftness. They are of a red color. The crocuttas [the spotted hyena] is, according to this author, of mixed progeny of a wolf and a dog. What Metrodorus the Scepsian relates, in his book "on Custom," is like fable, and to be disregarded. Artemidorus mentions serpents also of thirty cubits in length, which can master elephants and bulls: in this he does not exaggerate. But the Indian and African serpents are of a more fabulous size, and are said to have grass growing on their backs.

Strabo on the Elephant and Ostrich Eaters

ostrich egg from Ancient Egypt

Strabo wrote in “Geography” (A.D. 22): “Above is the city Darada, and a hunting-ground for elephants, called "At the Well." The district is inhabited by the Elephantophagi (or Elephant-eaters), who are occupied in hunting them. When they descry from the trees a herd of elephants directing their course through the forest, they do not then attack, but they approach by stealth and hamstring the hindmost stragglers from the herd. Some kill them with bows and arrows, the latter being dipped in the gall of serpents. The shooting with the bow is performed by three men, two, advancing in front, hold the bow, and one draws the string. Others remark the trees against which the elephant is accustomed to rest, and, approaching on the opposite side, cut the trunk of the tree low down. When the animal comes and leans against it, the tree and the elephant fall down together. The elephant is unable to rise, because its legs are formed of one piece of bone which is inflexible; the hunters leap down from the trees, kill it, and cut it in pieces. The nomads call the hunters Acatharti, or impure. [Source: Strabo, “The Geography of Strabo:” XVI.iv.4-17; XVII.i.53-54, ii.1-3, iii.1-11, translated by H. C. Hamilton, esq., & W. Falconer (London: H. G. Bohn, 1854-1857), pp. 191-203, 266-272, 275-284]

“Above this nation is situated a small tribe — the Struthophagi (or Bird-eaters), in whose country [about modern Lake Tana] are birds of the size of deer, which are unable to fly, but run with the swiftness of the ostrich. Some hunt them with bows and arrows, others covered with the skins of birds. They hide the right hand in the neck of the skin, and move it as the birds move their necks. With the left hand they scatter grain from a bag suspended to the side; they thus entice the birds, until they drive them into pits, where the hunters despatch them with cudgels. The skins are used both as clothes and as coverings for beds. The Ethiopians called Simi are at war with these people, and use as weapons the horns of antelopes.

“Bordering on this people is a nation blacker in complexion than the others, shorter in stature, and very short-lived. They rarely live beyond forty years; for the flesh of their bodies is eaten up with worms. Their food consists of locusts, which the south-west and west winds, when they blow violently in the spring-time, drive in bodies into the country. The inhabitants catch them by throwing into the ravines materials which cause a great deal of smoke, and light them gently. The locusts, as they fly across the smoke, are blinded and fall down. They are pounded with salt, made into cakes, and eaten as food. Above these people is situated a desert tract with extensive pastures. It was abandoned in consequence of the multitudes of scorpions and tarantulas, called tetragnathi (or four-jawed), which formerly abounded to so great a degree as to occasion a complete desertion of the place long since by its inhabitants.

pet gazelle “Next to the harbor of Eumenes, as far as Deire and the straits opposite the six islands, live the Ichthyophagi, Creophagi, and Colobi, who extend into the interior. Many hunting-grounds for elephants, and obscure cities and islands, lie in front of the coast. The greater part are nomads; husbandmen are few in number. In the country occupied by some of these nations styrax grows in large quantity. The Icthyophagi, on the ebbing of the tide, collect fish, which they cast upon the rocks and dry in the sun. When they have well-broiled them, the bones are piled in heaps, and the flesh trodden with the feet is made into cakes, which are again exposed to the sun and used as food. In bad weather, when fish cannot be procured, the bones of which they have made heaps are pounded, made into cakes and eaten, but they suck the fresh bones. Some also live upon shellfish, when they are fattened, which is done by throwing them into holes and standing pools of the sea, where they are supplied with small fish, and used as food when other fish are scarce. They have various kinds of places for preserving and feeding fish, from whence they derive their supply.

“Some of the inhabitants of that part of the coast which is without water go inland every five days, accompanied by all their families, with songs and rejoicings, to the watering places, where, throwing themselves on their faces, they drink as beasts until their stomachs are distended like a drum. They then return again to the sea-coast. They dwell in caves or cabins, with roofs consisting of beams and rafters made of the bones and spines of whales, and covered with branches of the olive tree. The Chelonophagi (or Turtle-eaters) live under the cover of shells (of turtles), which are large enough to be used as boats. Some make of the sea-weed, which is thrown up in large quantities, lofty and hill-like heaps, which are hollowed out, and underneath which they live. They cast out the dead, which are carried away by the tide, as food for fish.

In Ancient Egypt 38 Large Mammals; Today. Eight

Virginia Gewin wrote in Nature: “Ancient Egyptian rock inscriptions and carvings on pharaonic tombs chronicle hartebeest and oryx — horned beasts that thrived in the region more than 6,000 years ago. Researchers have now shown that those mammal populations became unstable in concert with significant shifts in Egypt’s climate. [Source: Virginia Gewin, Nature, August 8, 2013 ~]

“The finding is based on a fresh interpretation of an archaeological and palaeontological record of ancient Egyptian mammals pieced together more than a decade ago by the zoologist Dale Osborn. Thirty-eight large-bodied mammals existed in Egypt roughly six millennia ago, compared to just eight species today. “There are interesting stories buried in the data — at the congruence of the artistic and written record,” says Justin Yeakel, an ecologist at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, British Columbia, who presented the research this week at the annual meeting of the Ecological Society of America in Minneapolis, Minnesota. For example, the philosopher Aristotle said 2,300 years ago that lions were present, though rare, in Greece; shortly thereafter, the beasts appeared in the local art record for the last time, Yeakel says. ~

“Overlaying records of climate and species occurrences over time, his team found that three dramatic declines in Egypt’s ratio of predators to prey coincided with abrupt climate shifts to more arid conditions. The timing of these aridification events also corresponds to major shifts in human populations at the end of the African Humid Period, about 5,500 years ago; during the Akkadian collapse, about 4,140 years ago in what is now Iraq; and about 3,100 years ago, when the Ugaritic civilization collapsed in what is now Syria. ~

trading a giraffe “Once they found the climate correlation, Yeakel and Mathias Pires, an ecological modeller from the University of Sao Paolo in Brazil, examined the consequences of the ancient extinctions on food-web stability. The researchers adapted a method for modelling food-web interactions with limited data. They simulated millions of potential predator–prey interactions using data about species’ body sizes. Tests using data from modern Serengeti food webs suggest the model correctly predicts 70% of predator-prey interactions. ~

“Normally, as food webs get smaller, they become more stable, says Yeakel. But his simulations showed that the proportion of stable food webs in Egypt declined over time, with the largest drop in stability occurring over the past 200 years. “Food webs are giant messy networks,” says Carl Boettiger, a computational ecologist at University of California, Santa Cruz, who was not involved with the work. “This approach is a powerful way to infer the stability of the food web without knowing specifically who eats who, much less the whole network structure,” he adds. ~

“Yeakel and his colleagues confirmed that the extinction patterns in Egypt cannot be explained by random events. They also found that the presence or absence of any one species did not seem to have much impact on a food web — in sharp contrast to conditions today in many landscapes, possibly owing to rapid changes caused by human encroachment. “We’ve lost redundancy in ecosystems,” Yeakel says, “which is why the absence of any one species can alter the stability of the system.” ~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024