Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society / Culture, Science, Animals and Nature

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CALENDAR

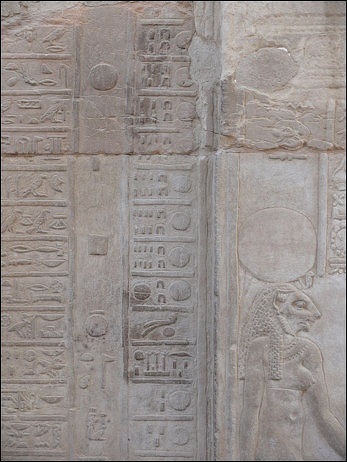

Calendar at Kom Ombo

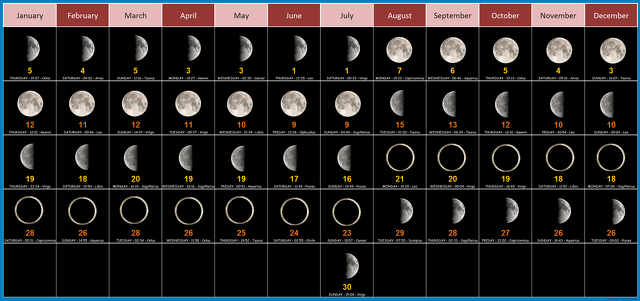

Although Mesopotamians devised the first calendars the Egyptians conceived the modern 365-day, 12 month calendar. Egypt devised a 365-day calendar as early as the 5th millennium based on flood of the Nile which occurred at almost the same time every year. The Egyptian year began in July when the Nile usually flooded and was marked by the rising of the star Sirius in the eastern horizon just before daybreak.

Egyptians added five days to the 360-day calendar, consisting of twelve 30-day months. The ancient Egyptian civil calendar had three seasons: 1) Akhet (Flooding); 2) Peret (Growing or Sowing); and 3) Shemu (Harvest). Each season had four months with 30 days. The additional five days were tacked onto the end of Harvest and set aside for feasting during the annual flooding of the Nile. The Hindus and Chinese also used 365-day calendars.

The Egyptians discovered that not only did the star Sirius line up with the rising sun around the time of flooding every year they also noticed that Sirius lined up with the sun about six hours (a ¼ a day) different every year. They were among the first people to realize the need for a leap day. For a while they inserted a leap day into their calendar but then abandoned it. This meant their calendar would slip a day every four years and an entire month every 120 years.

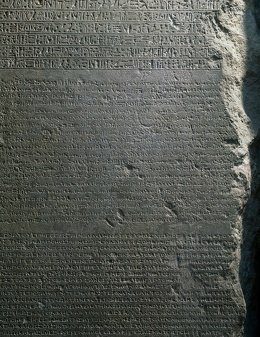

A trilingual description of changes to be made to the Egyptian calendar have been found at several places, including the temple of Bubastis, the 8th century capital of Egypt. The 2,200-year-old stelae described planned changes for the Egyptian calendar that were implemented 250 years later by Julius Caesar (See Leap Year Below).

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Ritual Year In Ancient Egypt: Lunar & Solar Calendars and Liturgy”

by Mogg Morgan (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Calendar : The 5000 Year Struggle to Align the Clock and the Heavens and What Happened to the Missing Ten Days” by David Ewing Duncan (1999) Amazon.com;

“Time in Antiquity” by Robert Hannah Amazon.com;

Festivals and Calendars of the Ancient Near East” by Mark Cohen (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Biblical Calendar Then and Now: by Bill Bishop and Karen Bishop (2018) Amazon.com

“Dendera, Temple of Time: The Celestial Wisdom of Ancient Egypt” by José María Barrera (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Science, Vol. II: Calendars, Clocks, and Astronomy, Memoirs, American Philosophical Society by Marshall Clagett (1995) Amazon.com;

“Astronomy, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World: Parapegmata and Related Texts in Classical and Near-Eastern Societies” (Reissue Edition) by Daryn Lehoux Amazon.com;

“Royal Festivals in the Late Predynastic Period and the First Dynasty” by Alejandro Jiminez Serrano (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Discoverers” by Daniel Boorstin (1985) Amazon.com;

“Sundials: Their Theory and Construction” by Albert Waugh (1973) Amazon.com;

“Down to the Hour: Short Time in the Ancient Mediterranean and Near East (Time, Astronomy, and Calendars: Texts and Studies” by Kassandra J. Miller (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Timepiece of Shadows: a History of the Sun Dial”

by Henry Spencer Spackman (1895) Amazon.com;

Ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian Concepts of Time

The Egyptians invented the 24 hour day and helped pioneer the concept of time as an entity. They divided the day into two cycles of 12 hours each. The origin of the 12-hour division might come from star patterns in the sky or from the Sumerian number system which was based on the number 12.

The Babylonians are often given credit for devising the first calendars, and with them the first conception of time as an entity. They developed and used the 360-day year — divided into 12 lunar months of 30 days (real lunar months are 29½ days) — devised by the Sumerians and introduced the seven day week, corresponding to the four waning and waxing periods of the lunar cycle. The ancients Egyptians adopted the 12-month system to their calendar. The ancient Hindus, Chinese, and Egyptians, all used 365-day calendars.

The Babylonians stuck stubbornly to the lunar calendar to define the year even though 12 lunar months did not equal one year. In 432 B.C., the Greeks introduced the so-called Metonic cycle in which every 19 years seven of the years had thirteen months and 12 years had 12 months. These kept the seasons in synch with the year and the roughly kept the days and months of the Metonic year in sync with those on the lunar calendar. The Metonic calendar was too complicated for everyday use and used mostly by astronomers.

The Mesopotamians also invented the 60 minute hour. The idea of measuring the year was more important than measuring the day. People could judge the time of day by following the sun. Judging the time of year was more difficult and important in knowing when to plant crops, expect rain or snow and harvest crops. That is why a yearly calendar was developed before clocks and minutes and seconds didn’t come to the Middle Ages.

The Babylonians have been credited with coming up with the idea of dividing the hour into 60 minutes. The number 60 seemed to be prized especially since 360 divided by six is 60 and some scholars have speculated that is why hours are made up of 60 minutes and minutes are made up of 60 seconds. Other believe the number 60 was arrived at by multiplying the visible planets (5, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) by the number of months (12).

See Separate Article: CALENDARS, TIME MEASUREMENTS AND SEASONS IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian 365-Day Year

Ancient Egyptian calendar at Elephantine Island

The first references to a 365-day calendar, which specify a year of twelve 30-day months and 5 epagomenal days (‘monthless days’ added to the calendar to make it approximately equal to the solar year) are found in the records of Egypt’s Fourth and Fifth Dynasties around 2600 B.C., according to Adrienn Almàsy-Martin, an Egyptologist at the University of Oxford. The inaccuracy this introduces is sufficient to cause a slow drift of the seasons through the calendar.

Indi Bains wrote in National Geographic History: The ancient Egyptians noticed a celestial coincidence that occurred annually at the same time as the flooding of the Nile — the appearance of Sirius, the brightest star in the sky. In the same way that some constellations are not visible all year, Sirius was not visible to the ancient Egyptians for the same 70 contiguous days of every year because it was too close to the sun. Annually after this absence, Sirius would reappear on the eastern horizon in the dawn sky, rising close to and just before the sun — a phenomenon known as “heliacal rising.” [Source: Indi Bains, National Geographic History, February 22, 2024]

Egyptian civilization depended upon the Nile floods to bring the rich silt that fertilized its farmlands. The reappearance of Sirius, linked as it was to the crucial Nile inundation, and which also occurred at the summer solstice, was keenly observed, and heralded the beginning of the ancient Egyptian new year. By measuring the elapsed time between each annual heliacal rising of Sirius, astronomers eventually realized the solar year was a quarter-day longer than 365 days. While this realization likely happened earlier in history, the Canopus Decree of 238 B.C. is our earliest recorded evidence for the leap year.

2,200-Year-Old Slab Contains the World’s First Mention of Leap Year

The Tanis Stele is a limestone slab is more than two meters (seven feet) tall and nearly one meter (three feet) wide. Discovered in 1866 by German scholars visiting the site of the ancient Egyptian city of Tanis in the Nile Delta, it bears an inscription in two languages — Egyptian (written in both hieroglyphs and Demotic script) and ancient Greek — like the more-famous Rosetta Stone. The inscription, dated to 238 B.C., is a copy of the Canopus Decree for Pharaoh Ptolemy III and follows the standard of the time, including praise for the pharaoh and descriptions of military campaigns. [Source:Indi Bains, National Geographic History, February 22, 2024]

It also contains the oldest known reference to leap year, which reads: “And so that the seasons should always correspond to the established order of the universe, and that it should not happen that some of the public festivals which take place in winter are celebrated in summer, as the sun changes by one day in the course of four years… (it was resolved) to add from now onwards one festival day in honor of the gods…every four years to the five additional days, before the new year, so that all may now know that the former defect in the arrangement of the seasons…”

Indi Bains wrote in National Geographic History: Multiple copies of the Canopus Decree would have existed in ancient times, according to Almàsy-Martin, and six complete or fragmented versions of the decree have survived to this day. The two best-preserved examples — from Tanis in 1866 and the site of Kom el-Hisn, in 1881 — are in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. While they were discovered after the decipherment of the Rosetta Stone in 1822, the better-preserved examples of the Canopus Decree feature a greater number of hieroglyphs and their study ended all remaining doubt about the Rosetta’s decipherment. For this reason, their inscription is considered second only to the Rosetta’s in significance for understanding ancient Egyptian.

We know Ptolemy III’s directive in the Canopus Decree to add an additional day to the calendar every four years was ultimately unsuccessful, but not when or why his directions were ignored. It is possible the priests controlling the calendar didn’t want to change their traditions, or perhaps they thought the drift of the seasons through the calendar was unnoticeable within a typical 40-year lifetime. What we do know is that when the Romans annexed Egypt in 30 B.C., the Egyptians were again using a 365-day calendar, and by 22 B.C — a few years after the Egyptian-inspired Julian calendar had been implemented in Rome — Emperor Augustus had reintroduced the leap day back to the Egyptians.

Ancient Egyptian Calendar System

The Egyptians devised the solar calendar by recording the yearly reappearance of Sirius (the Dog Star) in the eastern sky. It was a fixed point which coincided with the yearly flooding of the Nile. Their calendar had 365 days and 12 months with 30 days in each month and an additional five festival days at the end of the year. However, they did not account for the additional fraction of a day and their calendar gradually became incorrect. Eventually Ptolemy III added one day to the 365 days every four years. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: The calendar system of ancient Egypt is unique to both the cosmology of the Egyptians and their religion. Unlike the modern Julian calendar system, with it's 365 days to a year, the Egyptians followed a calendar system of 360 days, with three seasons, each made up of 4 months, with thirty days in each month. The seasons of the Egyptians corresponded with the cycles of the Nile, and were known as Inundation (pronounced akhet which lasted from June 21st to October 21st), Emergence (pronounced proyet which lasted from October 21st to February 21st), and Summer (pronounced shomu which lasted from February 21st to June 21st). [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“The beginning of the year, also called "the opening of the year", was marked by the emergence of the star Sirius, in the constellation of Canis Major. The constellation emerged roughly on June 21st., and was called "the going up of the goddess Sothis". The star was visible just before sunrise, and is still one of the brightest stars in the sky, located to the lower left of Orion and taking the form of the dogs nose in the constellation Canis Major. +\

“Though the Egyptians did have a 360 day calendar, in a literal sense they did have a 365 day calendar system. The beginning of the year was marked by the addition of five additional days, known as "the yearly five days". These additional five days, were times of great feasting and celebration for the Egyptians, and it was not uncommon for the Egyptians to rituals, and other celebratory dealings on these days. The Egyptian calendar also took on other important functions within Egyptian life specifically in dealing with the astrology of the people. “ +\

Importance of Solstices to Ancient Egyptians

The summer solstice generally coincided with the peak of the annual Nile flood, which was key to Egypt’s agricultural success. Both the summer and the winter solstice were associated with resurrection.[Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, March/April 2023]

The ancient Egyptians appeared to have valued the winter solstice based on the position of some buildings and tombs. Why was this so? Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: The winter solstice had an important meaning for the ancient Egyptians, researchers told Live Science. "The winter solstice marked the beginning of the daily victory of light against darkness, culminating in the summer solstice, the longest day on the earthly plane," study lead author María Dolores Joyanes Díaz, a researcher at the University of Málaga in Spain, told Live Science. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, November 29, 2022]

Moreover, the solstice was seen as a moment of renewal. "After the winter solstice the days begin to be longer, which was interpreted as a rebirth," Jiménez-Serrano added. "This concept was transferred to [the] physic[al] world, specifically to the statue that represented the dead governor."

"I would understand it within the common sun cult as a symbol of new beginnings and resurrection," Lara Weiss, a curator of the Egyptian and Nubian collection at the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, the Netherlands, told Live Science. "The winter solstice could be interpreted as [the] beginning of the annual course of the sun."

Herodotus on the Egyptian Calendar

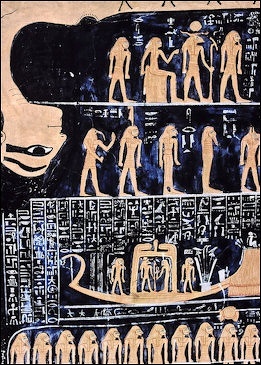

Goddess Nut with humans representing stars, from the tomb of Ramses VI

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “But as to human affairs, this was the account in which they all agreed: the Egyptians, they said, were the first men who reckoned by years and made the year consist of twelve divisions of the seasons. They discovered this from the stars (so they said). And their reckoning is, to my mind, a juster one than that of the Greeks; for the Greeks add an intercalary month every other year, so that the seasons agree; but the Egyptians, reckoning thirty days to each of the twelve months, add five days in every year over and above the total, and thus the completed circle of seasons is made to agree with the calendar. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“Furthermore, the Egyptians (they said) first used the names of twelve gods4 (which the Greeks afterwards borrowed from them); and it was they who first assigned to the several gods their altars and images and temples, and first carved figures on stone. Most of this they showed me in fact to be the case. The first human king of Egypt, they said, was Min. In his time all of Egypt except the Thebaic5 district was a marsh: all the country that we now see was then covered by water, north of lake Moeris,6 which is seven days' journey up the river from the sea.

“Other things originating with the Egyptians are these. Each month and day belong to one of the gods, and according to the day of one's birth are determined how one will fare and how one will end and what one will be like; those Greeks occupied with poetry exploit this. More portents have been discovered by them than by all other peoples; when a portent occurs, they take note of the outcome and write it down; and if something of a like kind happens again, they think it will have a like result. As to the art of divination among them, it belongs to no man, but to some of the gods; there are in their country oracles of Heracles, Apollo, Athena, Artemis, Ares, and Zeus, and of Leto (the most honored of all) in the town of Buto. Nevertheless, they have several ways of divination, not just one.”

Ancient Egyptian Astrology and the Cairo Calendar

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: Most of our understanding of Egyptian astrology is contained within the Cairo Calendar, which consists of a listing of all the days of an Egyptian year. The listings within the calendar all take the same form and can be broken up into three parts: I, the type of day (favorable, unfavorable etc), II, a mythological event which may make a particular day more favorable or unfavorable, III, and a prescribed behavior associated with that day. Unlike modern astrology as found within newspapers, where one can choose whether to follow the advice there in or not, the Egyptians strictly adhered to what an astrologer would advise. As is evidenced by the papyrus of the Cairo Calendar, on days where there were adverse or favorable conditions, if the astrologers told a person not to go outside, not to bathe, or to eat fish on a particular day, such advice was taken very literally and seriously. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“Some of the most interesting and misunderstood information about the Ancient Egyptians concerns their calendarical and astrological system. Of the greatest fallacy about Ancient Egypt and it's belief in astrology concerns the supposed worship of animals. The Egyptians did not worship animals, rather the Egyptians according to an animals astrological significance, behaved in certain ritualistic ways toward certain animals on certain days. For example, as is evidenced by the papyrus Cairo Calendar, during the season of Emergence, it was the advisement of the Seers (within the priestly caste), and the omens of certain animals they saw, which devised whether a specific date would be favorable or unfavorable. +\

“The basis for deciding whether a date was favorable or unfavorable was based upon a belief in possession of good or evil spirits, and upon a mythological ascription to the gods. Simply, an animal was not ritually revered because it was an animal, but rather because it had the ability to become possessed, and therefore could cause harm or help to any individual near them. It was also conceived of that certain gods could on specific days take the form of specific animals. Hence on certain days, it was more likely for a specific type of animal to become possessed by a spirit or god than on other days. The rituals that the Egyptians partook of to keep away evil spirits from possessing an animal consisted of sacrifice to magic, however, it was the seers and the astrologers who guided many of the Egyptians and their daily routines. Hence, the origin of Egyptians worshipping animals, has more to do with the rituals to displace evil spirits, and their astrological system, more so than it does to actually worshipping animals.” +\

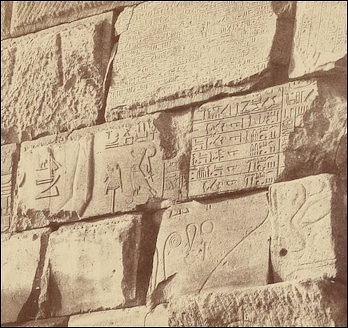

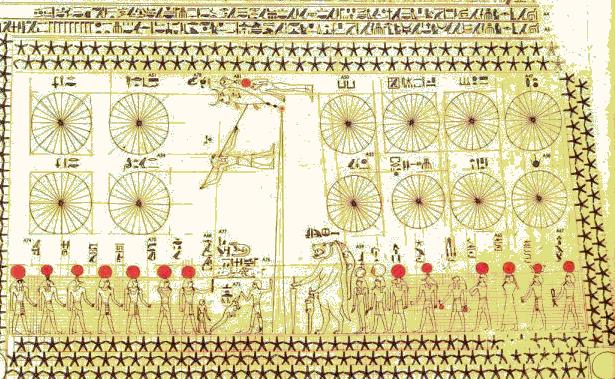

Calendar Senenmut-Grab

Links Between the Ancient Egyptian and Coptic Christian Calendar

Saphinaz-Amal Naguib of the University of Oslo wrote: “Cultural changes usually occur as part of long processes of transformation. However, some events may trigger rapid changes in a culture’s structures, generate innovations, and bring about new ways of life. The construction of the Aswan High Dam was such an event. Inaugurated in January 1971, the Aswan High Dam has radically altered Egypt’s ecology and led to the disappearance of most rituals and religious practices related to the Nile and its inundation. It has modified a cumulative body of local knowledge and made the agricultural calendar meaningless. Nevertheless, some religious practices tied to the seasonality of the Nile are still recognizable in Coptic Christianity. Their memory lingers on in the Coptic calendar, a solar calendar that is based on the ancient Egyptian one, which used to be the agricultural calendar of Egypt. For instance, like the ancient Egyptians, Copts celebrate their New Year (cayd el-nayruuz) on the first of Tuut, which corresponds to the month of September. Before the building of the Aswan High Dam, the river’s level attained its peak around the middle of the month. Land- taxes would not be collected before the Nile had reached the ideal height of sixteen cubits. The final level of the river was measured on the seventeenth of Tuut and was called “the level of the Cross.” The Coptic synaxarium reminds us that the day is dedicated to the Feast of the Cross (cayd el-saliib). [Source: Saphinaz-Amal Naguib, University of Oslo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“The third month of the year, Haatuur, begins with the three “nights of darkness,” during which Coptic liturgy is imbued with funerary tones. From an Egyptological point of view it harks of Plutarch’s statement that Osiris was killed during this month. Nothing in the Coptic liturgy reminds us of the mysteries of Osiris that were celebrated during Khoiak, the fourth month of the year. Yet during this month it is a custom among Egyptians, both Copts and Muslims, to sow seven types of grain on cotton-wool wrapped around a bottle or on the model of a doll cut in cardboard. The sprouting figure is considered as an omen of a “green year”—that is, a prosperous and happy one. The fifth month, Tuubah, was known for the quality and purity of the Nile’s water. People used to store mayyat Tuubah—Nile water drawn during this month— for special occasions. Big jars filled with it were placed near cemeteries, tombs of saints, and other pilgrimage sites. It was believed that the waters would cure diseases and prevent all kinds of ailments. Copts celebrate the Feast of Immersion (cayd el-ghitaas) commemorating the Baptism of Christ on the eleventh of Tuubah and visit their dead on the following day.

“In ancient Egypt solemnities commemorating the erection of the Djed-pillar were held during this month. The spring feast of shamm el-nasiim, which usually occurs during the month of Barmuudah, has been considered to derive from the ancient Egyptian Sokar Festival. The twelfth of Ba'uuna is dedicated to the archangel Michael, and the liturgy of that day includes prayers to the Nile. Before the building of the Aswan High Dam, this period coincided with the Night of the Drop (laylat el-nuqta), when the Nile was at its lowest level and the inundation period started. On that night a divine drop falling from the sky was said to initiate the rise of the Nile. To ancient Egyptians it corresponded with the appearance of the Dog Star, Sopdet (vocalized as Sothis by the Greeks), at dawn announcing the end of a cycle and the beginning of a new one. According to Pausanias, it was believed that during that night Isis mourning the loss of Osiris shed a tear, thus triggering the overflow. Furthermore, it is worth noting here that the archangel Michael seems to have taken over the characteristic of the god Thoth as regulator of the Nile.”

Egyptian calendar

“Coptic pilgrimages and mulids have gone through various developments giving way to innovations and hybridization. The term “mulid” (Arabic: mawlid, pl. mawaalid) stems from the root wld, meaning birth. It designates the birthday of a saint. More exactly, it marks the anniversary of the saint’s martyrdom or death and thereby her or his “rebirth.” By extension, mulid denotes the festivities held around the shrine of the saint, who is a center of pilgrimage. The shrine locality attracts fairs with all their various stalls and games. Mulids, whether Coptic or Muslim, pertain to popular religion and have been frowned upon by both religious and governmental authorities, which blame them for re-enacting pagan rituals, encouraging sexual licentiousness, and providing the grounds for the consumption of drugs. So much so that the term “mulid” signifies rowdiness and anarchy. Nevertheless, mulids are popular among people from different social backgrounds and until recently Copts and Muslims used to take part in each other’s mulids. Some mulids are recent creations, but the majority have a long history exemplifying the significance of a given site as a consecrated sacred space and bringing forth the descriptions of festivals dating back to the Pharaonic Period. Some saints and martyrs may have incorporated the characteristics of older local deities, but this is an opinion open to controversy.”

Ancient Egyptian Festivals

During ancient Egyptian festivals statues of the gods were carried by priests in a procession to other temples so they could visit with other gods. During a festival that celebrated the founding of the first Egyptian kingdom the pharaoh did a dance while wearing a short skirt with an animal tail hanging from behind it.

A "sexual union between the king and queen" was probably part of the Great fertility Festival of Min. During the Ptolemaic era an effigy of Osiris was sacrificed and then reborn with barley spraying from the top of the effigy like a sparklers from a Roman candle. ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Annual animal cult festivals were big events. A.R Williams wrote in National Geographic, “Like country fairs, these great gatherings enlivened religious centers up and down the Nile. Pilgrims arrived by the hundreds of thousands and setup camp. Music and dancing filled the processional rite. Merchants sold food, drink and souvenirs. Priests became salesmen, offering wrapped mummies, as well as more elaborate ones for people who cold spend more — or thought they should. With incense swirling all around, the faithful ended their journey by delivering their chosen mummy to the temple with a prayer.”

The key annual event occurred in midsummer, and it involved not only the sun but also the bright star Sirius (which they equated with the astral god Sothis). Every spring Sirius disappears for several weeks , hidden by the sun’s glare. The New Year began when Sirius first became visible again in the predawn sky, heralding the flooding of the Nile.

The Apis bull was one of the most revered animals in all of ancient Egypt. A.R. Williams wrote in National Geographic, “On the bull’s burial day, city residents surged into the streets to observe this occasion of national mourning. Wailing and tearing at their hair, they crowded the route at the catacomb now known as Serapeum in the desert necropolis of Saqqara. In a procession, priest temple, singers, and exalted officials delivered the mummy to the network of vaulted galleries carved into the bedrock of limestone. There among the long corridors of previous burials, they interred the mummy in a massive wooden or granite sarcophagus.”

See Separate Articles: FESTIVALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: PROCESSIONS, FEASTS, TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com OPET FESTIVAL OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024