Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

OPET FESTIVAL

The Opet Festival in Thebes was held annually during the season of Nile flooding. It celebrated the annual reunion of the Thebean Triad: the great god Amum, his wife Mut and their son Khonsu. Details of the ceremony are carved in a relief in the processionary colonnade in Luxor Temple.

The ceremony may be been developed by Queen Hatshepsut. Opet means "southern sanctuary," a reference to Luxor Temple, the southern temple in Thebes. The Opet Festival began on the nineteenth day of the second month of the flood (the end of August). Earlier versions of the festival lasted 11 days. By the 18th dynasty (1550-1298 B.C.) the festival was the main event on the Egyptian calendar. In Ramses II's time it continued for 27 days. The festival itself may have lasted into the Roman era.

The Egyptians believed that towards the end of annual agricultural cycle the gods and the earth became exhausted and needed a jolt from the chaotic energy of the cosmos to get the process going again. To achieve this goal magical regeneration was invoked at the annual Opet festival at Karnak and Luxor. Lasting for 27 days, it was also a celebration of the link between pharaoh and the god Amun. The main even t was procession that began at Karnak and ended at Luxor Temple, 2.4 kilometers (1½ miles) to the south. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com] John Darnell of Yale University wrote: “The annual Opet Festival, during which the bark of Amun—and ultimately those of Mut, Khons, and the king as well—journeyed from Karnak to Luxor, became a central religious celebration of ancient Thebes during the 18th Dynasty. The rituals of the Opet Festival celebrated the sacred marriage of Amun—with whom the king merged—and Mut, resulting in the proper transmission of the royal ka and thus ensuring the maintenance of kingship. [Source: John Darnell, Yale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Opet Festival, eponymous celebration of the month Paophi (second month of the Akhet season), was an annual event at the time of its earliest attestation during the reign of Hatshepsut . Opet began on II Akhet 15 under Thutmose III and lasted 11 days; by the beginning of the reign of Ramesses III, the festival stretched over 24 days, perhaps with three days added to the conclusion of the festival by the end of his reign (Grandet suggests a 24 day observance at Medinet Habu, with 27 days of festivities on the east bank). The eve of Opet was also observed , and a Festival of Amun that Occurs after the Opet Festival is also known. The final day of the festival occurred on III Akhet 2 during Piye’s visit to Thebes. The festival appears to have continued into the Roman Period, and echoes thereof may have survived in Coptic and Islamic celebrations as well.

“The name of the festival, Hb Ipt, relates to that of Luxor Temple, Ip(A)t-rsyt, which was perhaps the Upper Egyptian counterpart of an earlier Heliopolitan IpAt, the “southern” specification relating Luxor Temple to that northern shrine and not to Karnak; the Opet Festival’s relationship to Heliopolitan prototypes would explain a number of Heliopolitan toponyms that appear in Luxor Temple as probable references to portions or aspects of Luxor Temple itself. The participants may have considered the multiple-day event to consist of various sub- festivals grouped together.

See Separate Articles: FESTIVALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: PROCESSIONS, FEASTS, TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Royal Festivals in the Late Predynastic Period and the First Dynasty” by Alejandro Jiminez Serrano (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Ritual Year In Ancient Egypt: Lunar & Solar Calendars and Liturgy”

by Mogg Morgan (2014) Amazon.com;

Festivals and Calendars of the Ancient Near East” by Mark Cohen (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Festivals of Opet, the Valley, and the New Year: Their Socio-Religious Functions”

by Masashi Fukaya (2020) Amazon.com;

“Reliefs and Inscriptions at Luxor Temple, Volume 1: The Festival Procession of Opet in the Colonnade Hall” (1994) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Feast in Ancient Egypt” by Ellen Morris (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Food and Festivals” by Stewart Ross (2001) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Temple Ritual: Performance, Patterns, and Practice” by Katherine Eaton (2013) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Science, Vol. II: Calendars, Clocks, and Astronomy, Memoirs, American Philosophical Society by Marshall Clagett (1995) Amazon.com;

“Astronomy, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World: Parapegmata and Related Texts in Classical and Near-Eastern Societies” (Reissue Edition) by Daryn Lehoux Amazon.com;

“The Calendar : The 5000 Year Struggle to Align the Clock and the Heavens and What Happened to the Missing Ten Days” by David Ewing Duncan (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Biblical Calendar Then and Now: by Bill Bishop and Karen Bishop (2018) Amazon.com

Pictorial Evidence of the Opet Festival

John Darnell of Yale University wrote: “The ancient inscriptional sources for the events of the Opet Festival are primarily pictorial and mostly located within Karnak Temple: Hatshepsut and Thutmose III—Red Chapel, Karnak, and Deir el-Bahri; Thutmose III—Akhmenu, Karnak; Amenhotep III—third pylon, Karnak; Tutankhamen—colonnade hall, Luxor; Horemheb—court between the ninth and tenth pylons, Karnak; Sety I—hypostyle hall, Karnak; Ramesses II—court between the eighth and ninth pylons, Karnak; Ramesses III—bark shrine in first court, Karnak, and Medinet Habu; Herihor—Khons Temple, Karnak. Although no text overtly explains the significance of the event, the Opet-procession scenes of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III on the Red Chapel, and those of Tutankhamen in the colonnade hall, reveal a number of otherwise unattested aspects of the festival, with the scenes of Herihor in Khons Temple supplying additional details of the navigation; textually, the most explicit and nuanced indications of the significance of the festival are the songs recorded in Tutankhamen’s Opet scenes. [Source: John Darnell, Yale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Scene from the King's 30 year jubilee

“The earliest and one of the most informative series of scenes appears on the south side of the Red Chapel of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III at Karnak. These scenes reveal the transportation of the bark of Amun from Karnak along a land route; stopping at six bark shrines on the way to Luxor, Amun’s bark then returned to Karnak by water, his riverine barge towed by the royal barge. After a stop in the wsxt-Hbt, the festival courtyard of the temple, priests carried the portable bark to the chapel of Amenhotep I, Mn-mnw-Imn. To the accompaniment of singers, musicians, and acrobats, the bark finally made its way toward the Hwt-aAt (“the great mansion”) and ultimately the inner sanctuary of Karnak.

“Hatshepsut’s scenes attest six shrines—embellished with Osiride figures of the queen—along some portion of the route between Karnak and Luxor, the first in south Karnak possibly near the temple of Kamutef, the rest as yet unidentified. Portions of a structure of Hatshepsut, probably the shrine nearest the temple of Luxor, were incorporated into the bark shrine of Ramesses II in the first court, perhaps near the shrine’s original location. Although the assumed line of six shrines stretching between Karnak and Luxor—indicative of an entirely terrestrial journey—is uncertain, associations between the southern axis of Karnak and the Opet Festival support such a reconstruction. Only the bark of Amun appears under Hatshepsut, but by the reign of Tutankhamen, the barks of Amun, Mut, and Khons, along with that of the king, took part in the festival.

“The presence of Opet related scenes in the Akhmenu suggests that under the sole rule of Thutmose III, the festival may have begun in that temple. The bark of Amun would have exited the third pylon, as in the Tutankhamen scene on the west wall in the colonnade hall at Luxor. By the reign of Tutankhamen, and perhaps already under Amenhotep III, to judge from architectural evidence at Luxor Temple, the bark of Khons would have joined the procession in southern Karnak, before the entourage reached the area of the Mut Temple and the first of Hatshepsut’s shrines on the land route. Under Tutankhamen, after being joined by the bark of Mut, the procession then proceeded to the Nile embarkation, river west of Hatshepsut’s northernmost bark shrine. Although the New Kingdom riverine barge Amun-Userhat existed under Ahmose and some sort of vessel participated in the Beautiful Festival of the Wadi already during the early Middle Kingdom, the Opet scenes of Tutankhamen are the first to depict a river journey in both directions; the procession disembarked at Luxor (for a possible Luxor dock under Ramesses III, see Cabrol 2001: 607 - 608) and entered the court of Luxor Temple before the colonnade hall, ultimately through the west wall entrance of the Ramesside court. The text on a sphinx of Nectanebo I on the route between Karnak and Luxor describes the construction (refurbishment) of the route for Amun, r jr[=f] Xn=f nfr m Ipt rsyt, “so that he might carry out his good navigation in Luxor”, revealing that the basic sense of “navigation” would be the same for the deity traveling within the portable bark, both on the deck of the riverine barge and the shoulders of the priests.”

Early History of the Opet Festival

John Darnell of Yale University wrote: “Although the earliest attestation of the festival and the earliest surviving 18th Dynasty constructions at Luxor date to the reign of Hatshepsut, one expects an ultimate 11th Dynasty origin, as for the three other major nodes of the Theban festival cycle. A platform in the area of the ninth pylon at Karnak may date to the reign of Senusret I, suggesting the presence of a processional route leading south from Karnak, along the route of the later north- south axis, presumably connecting Middle Kingdom Karnak with a contemporaneous structure at or near the later Luxor Temple. [Source: John Darnell, Yale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

The reign of Amenhotep III molded the procession and its architectural destination into the forms we recognize. Amenhotep III embellished Luxor Temple considerably, notably with the colonnade hall, an elaborate bark shrine as columned hall (like the hypostyle hall at Karnak); he may also have constructed a maru-temple in association with the Opet Festival. The architecture of the rooms immediately south of the hypostyle hall of Luxor Temple suggests that the bark of the king, first visible in Tutankhamen’s Opet scenes, was already an element of the procession under Amenhotep III.

The transformation of Amenhotep III from an individual ruler to the personification of the royal ka through a blurring of the boundary between the person of the king and the royal ka-nature in the rear rooms of Luxor Temple suggests that the Opet Festival under Amenhotep III and his successors became amongst other things a ritual of reconfirming the transmission of the royal ka. A later ruler might also begin to mingle his identity with that of an earlier incarnation of the royal ka, and a statue of the celebrating ruler’s immediate (legitimate) predecessor may have participated in the festival.”

Rituals at the Opet Festival

The climatic rituals of the Opet Festival occurred in the Sacrarium of Amenophis III (next to the Courtyard of Amenophis III of Luxor Temple). The pharaoh followed his priests into the inner sanctums of Luxor temple where no one else was allowed to go and performed rites to renew the energy of the Pharaoh and the gods for another year. Describing the rite for Ramses II Rick Gore wrote in National Geographic, "Wearing the solar crown with solar disks, ram's horns and cobras — symbols of divine rule — Ramses offers flowers and incense, dropping an aromatic pellet into a burner...Arum returns fumes, thereby renewing Ramses's own divinity."♣

The ritual offering of flowers, associated with regeneration, intensified during the feast, and people presented them in holders shaped like anks. Festival attendees scraped dust from the temples for healing and devotion, a practice that still remains today. Egyptologist Salima Ikram of Cairo’s American University told U.S. News and World Report, “Men drink their temple scrapings in tea to become more potent — early Viagra! — and said that women circle ths stone scarab near Karnak’s sacred lake seven times as a fertility ritual Haggag el Uqsuri in Luxor is a modern “moulid” (festival) that honor’s Luxor’s patron saint, Abu el Haggag, a 12th century Sufi mystic. It is believed to be based on the ancient Egyptian Opet Festival.

During the festival the people were given over 11000 loaves of bread and more than 385 jars of beer, and some were allowed into the temple to ask questions of the god. The priests spoke the answers through a concealed window high up in the wall, or from inside hollow statues.

Procession at the Opet Festival

The focal point of the early version of the festival was a procession in which the statue of Amun-Re, carried by 30 priests, and the statues of Mut and Kohonsu, were transported in boat shrines from the Temple of Karnak to the Temple of Luxor. The statues remained in the sanctuary of Luxor Temple for a couple of days before being carried back to Karnak on sacred boats.

Large crowds of people came out for processions. Merrymakers sang hymns, drank wine, anointed themselves with unguent and placed flowers on their heads. Participants in the procession included the Pharaoh, royal charioteers, priests, incense burners, fan bearers, bureaucrats, soldiers, musicians, singers and dancers. Female acrobats performed to rhythm of castanets, drums and sistrum rattles and priests carried offerings such as cattle, gazelles, wine, fruit, bouquets and lotus flowers. ♀

An Egyptian feast by Edwin Longshed

In a later version of the festival the pharaoh and the statues were carried to Luxor on ceremonial barges, which moved upstream with sails and two lines pulled by men on the shore. At the end of the festival the barge was carried downstream by the current.

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “The statue of the god Amun was bathed with holy water, dressed in fine linen, and adorned in gold and silver jewellery. The priests then placed the god in a shrine and onto the ceremonial barque supported by poles for carrying. Pharaoh emerged from the temple, his priests carrying the barque on their shoulders, and together they moved into the crowded streets. A troop of Nubian soldiers serving as guards beat their drums, and musicians accompanied the priests in song as incense filled the air. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

At Luxor, Pharaoh and his priests entered the temple and ceremonies were performed to regenerate Amun, recreate the cosmos and transfer Amun’s power to Pharaoh. When he finally emerged from the temple sanctuary, the vast crowds cheered him and celebrated the guaranteed fertility of the earth and the expectation of abundant harvests.

John Darnell of Yale University wrote: “By the late 18th Dynasty, both legs of the procession traveled on the Nile, with accompanying elements keeping pace on land. Tutankhamen’s scenes allude to the terrestrial route by depicting two empty royal chariots, attended by charioteers—elements from the daily Amarna chariot ride of the royal Atenist couple in and out of Akhetaten, transported to Thebes and incorporated into the Opet Festival. The bark of the king makes its first appearance in the Opet-procession scenes of Tutankhamen at Luxor Temple as a carrier for the processional image of the divine ruler. The bark of the king leaves Karnak and returns thereto, but is not present in Luxor Temple in Tutankhamen’s scenes of the festival—apparently the king has merged with Amun during the procession into Luxor making the royal bark superfluous. Amun of Luxor appears to have been a fecundity figure, both ram- headed and ithyphallic anthropomorphic, related to Nubia and the inundation, appropriate both to the southern node of the east bank Theban festival cycle and to the ram-form of the deified ruler in Nubia. [Source: John Darnell, Yale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

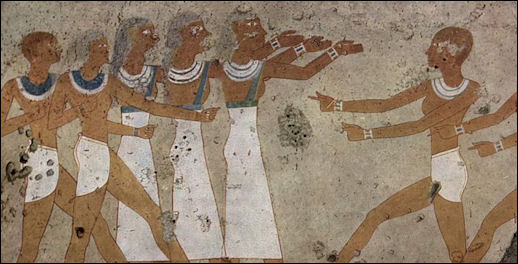

Participants of the Opet Festival

Scenes from the King's 30 year jubilee

John Darnell of Yale University wrote: “Accompanying the singing priests and priestesses are dancing foreigners: soldiers dressed as Libyans and using throwsticks as clappers, and Nubians leaping and swaying in a type of military dance with clubs. The presence of Nubians and Libyans is probably meant to evoke the groups amongst whom the solar eye goddess has recently sojourned, members of whom join her entourage for the return to Egypt. Also acrobatic dancers accompany the festival procession, the backward-leaning dance at once an evocation of the dance of the four winds and a display of eroticism. [Source: John Darnell, Yale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Soldiers and sailors are the most numerous of the festival participants in the colonnade hall scenes, and a number of military and civil officials participated in the preparations and execution of the Opet Festival; Ramesses II listed amongst those responsible for arranging the festival: members of the civil administration, provincial governors, border officials, heads of internal economic departments, officers of the commissariat, city officials, and upper ranks of the priesthood. In addition to overseeing aspects of the food preparation and rowing and towing the divine barges, at least one military official pronounces a hymn in honor of the king in front of the Opet-procession as it heads to Luxor on the west interior wall of the colonnade hall.

“The general populace appears to have been able to observe from the riverbanks, and at least some may have had limited access to the forepart of the temple. Celebrants may also have observed the event at other locations, such as the mortuary temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu, and a transplantation to Abydos appears to have occurred. Oracular manifestations of Amun could also occur during the festival, further relating events of the festival procession to the populace. During the second regnal year of a late 21st Dynasty ruler, the bark of Amun refused to leave his sanctuary for the Opet Festival, which finally took place sixty-five days later than usual, on day 23 of Khoiak, after the priest whose offenses occasioned the delay had appeared before a tribunal.”

Consummation of the Divine Union at the Opet Festival

Sed Festival scene

John Darnell of Yale University wrote: “Opet was not, however, solely a festival of royal identification with Amun. The riverine procession and the divine birth chamber become in late temple ritual the navigation of a god or goddess to the other to consummate the union that will result in the divine birth of the child god depicted—in borrowing from royal iconography of the New Kingdom—in the birth chamber of the temple, the mammisi. Opet was also a hieros gamos, a divine marriage, the result of which was the renewal of Amun in the person of his ever- renewing human vessel, the reigning king. [Source: John Darnell, Yale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

As the Amun-Min procession related the physical ruler to his predecessors, so the Opet Festival celebrated the renewal of the ka-force of Amun, and the transmission of the spirit of kingship in the eternal present. As a festival of annual renewal, the Opet Festival could reconfirm the royal coronation, which under Horemheb actually occurred at the time of the Opet Festival. The final major festival of Luxor, the Decade Festival with its visit to Medinet Habu, brought Amun of Luxor into contact with the entropic forces of death through his meeting with the primeval and transcendental forms of Amun and the Ogdoad on the west bank of Luxor.

“The union of a god with his temple may appear as a sexual union, and the nautical element of the Opet Festival is appropriate to a divine marriage ritual. Although absent from later Opet scenes, Hatshepsut’s Red Chapel records a harpist singing a song referring to the ithyphallic form of the double-plumed Amun, raised of arm (Dsr-a). Songs in the tomb of Amenemhat also refer to the appearance of the god from the temple and describe the temple of Karnak as a woman, drunk in religious ecstasy and attired in erotically Hathoric coiffure, awaiting with bed linens the arrival of the god—although that song is not clearly specific to Opet, the content may mirror that of the unrecorded song of the Red Chapel’s Opet harpist.”

Opet Festival Songs

John Darnell of Yale University wrote: “The Tutankhamen scenes record the texts of three songs accompanying the navigations, chanted by priests and priestesses. First Song:

“Oh Amun, Lord of the Thrones of the Two[Lan]ds, may you live forever!

A drinking place is hewn out, the sky is folded back to the south;

a drinking place is hewn out, the sky is folded back to the north;

that the sailors of Tutankhamen (usurped by Horemheb), beloved of Amun-Ra-Kamutef,

praised of the gods, may drink.” [Source: John Darnell, Yale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The directions, south and north, may allude to the southeast to northwest flight of the sun . The implied south to north journey of this song—like the actual return to Karnak from Luxor at the end of the Opet Festival—relates to the royal New Year’s Festival and the return of the wandering solar goddess from the south. The drinking place would be one of the booths that celebrants erected during nautical festivals. Such booths are consistent with the aspect of sexual union inherent in the Opet Festival; Neith probably appears in her role as “Lady of inebriation in the (season of) the fresh inundation waters”. The journey by land and a return by river—as the Opet Festival appears under Hatshepsut and Thutmose III—would thus evoke the dry period prior to the union of the god and returning solar goddess, the return to the north by river likewise emphasizing the returning flood. The journey to the south by land, and the towing of the barks against the current in the southerly riverine journey, also mirrored the nocturnal journey of the sun in the dry realms of the Land of Sokar. The sails of the barks appear to have been red in color, the return journey to Karnak thus evoking the red light of dawn, the veil of the new born solar deity.

“Second Song: Recitation:

“Hail, Amun, primeval one of the Two Lands, foremost one of Karnak,

in your glorious appearance amidst your [riverine] fleet,

on your beautiful Festival of Opet— May you be pleased with it.”

Third Song:: Recitation four times—Recitation for the bark:

“A drinking place is built for the party, which is in the voyage of the fleet.

The ways of the Akeru are bound up for you; Hapi is high.

May you pacify the Two Ladies, oh Lord of the White Crown/Red Crown.

It is Horus, strong of arm, who conveys the god with she the good one of the god.

For the king has Hathor already done the best of good things.”

Festival Hall of Thutmose III

The ways of Aker allude to the east/west axis of the solar journey, parallel to the first song’s “royal” south/north axis The songs associate the festival journey to the course of the sun , and at the same time allude to sexuality. The “best of good things” finds echoes in New Kingdom love poetry, a term for the consummation of sexual union. A further detail confirming the sexual aspect of the festival is a statement of a priest who bends forward and addresses the bark of Amun as it emerges from Luxor Temple at the end of the Opet Festival: “How weary is the cackling goose!”. This short statement alludes to the cry of creation uttered by the great cackler in the eastern horizon, appropriate to the smn-goose form of Amun as the deity prepares to sail to Karnak.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024