Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society / Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN FESTIVALS

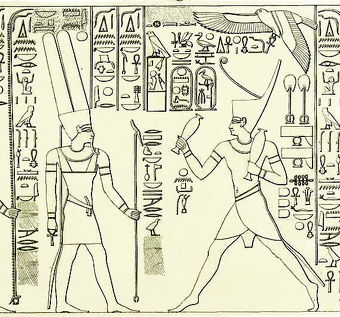

During ancient Egyptian festivals statues of the gods were carried by priests in a procession to other temples so they could visit with other gods. During a festival that celebrated the founding of the first Egyptian kingdom the pharaoh did a dance while wearing a short skirt with an animal tail hanging from behind it.

A "sexual union between the king and queen" was probably part of the Great fertility Festival of Min. During the Ptolemaic era an effigy of Osiris was sacrificed and then reborn with barley spraying from the top of the effigy like a sparklers from a Roman candle. ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

During festivals offerings were made and incense was burned. In certain cases other ceremonies were added as well, For example, at Aysut under the Middle Kingdom,' lamps were lighted before the statue of the deceased on the first and last days of the year. At other festivals, also on the same days, friends came to the temple singing songs in praise of the departed. Among the main events, particularly during the Old Kingdom, as we gather from the countless representations of I them, was the slaughter of sacrificial animal such as an ox or an antelope. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

See Separate Article: SACRIFICES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: PIGS, BULLS AND POSSIBLY HUMANS africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Royal Festivals in the Late Predynastic Period and the First Dynasty” by Alejandro Jiminez Serrano (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Ritual Year In Ancient Egypt: Lunar & Solar Calendars and Liturgy”

by Mogg Morgan (2014) Amazon.com;

Festivals and Calendars of the Ancient Near East” by Mark Cohen (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Festivals of Opet, the Valley, and the New Year: Their Socio-Religious Functions”

by Masashi Fukaya (2020) Amazon.com;

“Reliefs and Inscriptions at Luxor Temple, Volume 1: The Festival Procession of Opet in the Colonnade Hall” (1994) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Feast in Ancient Egypt” by Ellen Morris (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Food and Festivals” by Stewart Ross (2001) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Temple Ritual: Performance, Patterns, and Practice” by Katherine Eaton (2013) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Science, Vol. II: Calendars, Clocks, and Astronomy, Memoirs, American Philosophical Society by Marshall Clagett (1995) Amazon.com;

“Astronomy, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World: Parapegmata and Related Texts in Classical and Near-Eastern Societies” (Reissue Edition) by Daryn Lehoux Amazon.com;

“The Calendar : The 5000 Year Struggle to Align the Clock and the Heavens and What Happened to the Missing Ten Days” by David Ewing Duncan (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Biblical Calendar Then and Now: by Bill Bishop and Karen Bishop (2018) Amazon.com

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Ancient Egyptian Calendars

Although Mesopotamians devised the first calendars the Egyptians conceived the modern 365-day, 12 month calendar. Egypt devised a 365-day calendar as early as the 5th millennium based on flood of the Nile which occurred at almost the same time every year. The Egyptian year began in July when the Nile usually flooded and was marked by the rising of the star Sirius in the eastern horizon just before daybreak.

Egyptians added five days to the Babylonian 360-day calendar. The ancient Egyptian civil calendar had three season: 1) Akhet (Flooding); 2) Peret (Growing or Sowing); and 3) Shemu (Harvest). Each season had four months with 30 days. The additional five days were tacked onto the end of Harvest and set aside for feasting during the annual flooding of the Nile. The Hindus and Chinese also used 365-day calendars.

The Egyptians discovered that not only did the star Sirius line up with the rising sun around the time of flooding every year they also noticed that Sirius lined up with sun about six hours (a ¼ a day) different every year. They were among the first people to realize the need for a leap day. For a while they inserted a leap day into their calendar but then abandoned it. This meant their calendar would slip a day every four years and an entire month every 120 years.

A trilingual description of changes to be made to the Egyptian calendar was found at the temple of Bubastis, the 8th century capital of Egypt. The 2,200-year-old stellate described planned changes for the Egyptian calendar that were implemented d250 years later by Julius Caesar.

See Separate Articles: CALENDARS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

New Year’s in Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptian New Year occurred in mid-July on our calendar, Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The ancient Egyptian festival of Wepet Renpet (“opening of the year”) that celebrated the new year was not just a time of rebirth — it was dedicated to drinking. Archeological discoveries at the Temple of Mut in Egypt have revealed that during the reign of Hatshepsut the first month of the year included a “Festival of Drunkenness.” The festival was based on a myth in which the god Seth saved mankind from the war mongering goddess Sekhmet when he got her blackout drunk.[Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 31, 2014]

In October 2023, archaeologists announced that they had uncovered a New Year's scene from ancient Egypt painted on roof of the 2,200-year-old Temple of Esna. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: The paintings show the Egyptian deities Orion (also called Sah), Sothis and Anukis on neighboring boats with the sky goddess Nut swallowing the evening sky above them — a mythology that details the Egyptian New Year, according to a statement from the University of Tübingen in Germany, which jointly led the restoration with the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, October 19, 2023]

In the depiction, Orion represents the constellation of the same name, while Sothis represents Sirius, a star which was invisible in the night sky in ancient Egypt for 70 days of the year before becoming visible again in east, that day marking the ancient Egyptian New Year, Christian Leitz, an Egyptology professor at the University of Tübingen who is part of the team, said in the statement. The Nile seasonally flooded at this time, and the ancient Egyptians believed that about 100 days after the appearance of Sirius, the goddess Anukis was responsible for the receding of the Nile's flood waters. As the team finished cleaning the ceiling, they restored several other paintings. One of them — a representation of a lion's body with four wings and a ram's head — represents the "south wind," according to an inscription. In ancient Egypt, the south wind was associated with scorching heat and it's possible that the "lion represents the power of the heat," Leitz said.

Processions in Ancient Egypt

Processions were a fixture of festivals and funerals in ancient Egypt. Martin Stadler of Wuerzburg University wrote: “Egyptian processions were performed, and acquired meaning, in a religious context. Funeral processions, for example, symbolized the deceased’s transition into the hereafter. The most important processions, however, were the processions of deities that took place during the major feasts, especially those feasts that recurred annually. [Source: Martin Stadler, Wuerzburg University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

The deity left his or her sanctuary on these occasions and thus provided the only opportunities for a wider public to have more or less immediate contact with the deity’s image, although in most cases it still remained hidden within a shrine. These processions often involved the journey of the principal deity of the town to visit other gods, not uncommonly “deceased” ancestor gods who were buried within the temple’s vicinity. The “wedding” of a god and his divine consort provided yet another occasion for a feast for which processions were performed.

“They may be categorized as either processions of deities, in which royal processions would be included, or funeral processions. Processions of deities may be subdivided into those that took place within the temple and those that exited the temple. The former were not open to the wider public but had a profound impact on the architectural design of a temple, because the deity’s statue was carried around to “visit” interior stations or chapels, or—at least from the Late Period onward—the deity’s earthly manifestation was brought to the temple’s roof for the cosmic rejuvenation of the god through ritual unification with the sun, as part of the celebration of the rites of the New Year’s feast. Alongside these internal processional ways, votive statues were erected by the Egyptian elite to guarantee their permanent (even posthumous) presence in the audience whenever a deity epiphanized.

See Separate Article: PROCESSIONS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Major Festivals in Ancient Egypt

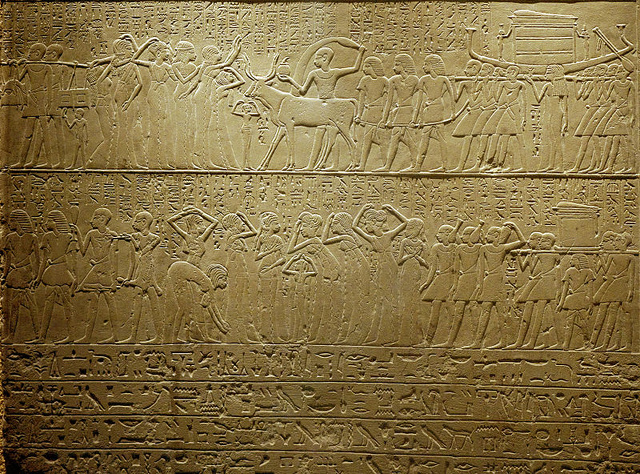

The Heb-Sed festival was "one of the most important feasts for ancient Egyptians that celebrates the end of the 30th year of the king's ascension to the throne," Abdel Rahim Rihan, director general of research, archaeological studies and scientific publication in South Sinai at the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, told Al-Monitor. "The depictions of this festival show the king on his throne in full strength, with the crowds around him happy and excited, waiting for his speech promising them another 30-year reign full of prosperity and opulence. On this occasion, the king would also make offerings to the gods." During the festival's highpoint, the pharaoh would have run around a race track in the courtyard to demonstrate his physical prowess, Rahim Rihan added. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, published January 25, 2022]

Annual animal cult festivals were big events. A.R Williams wrote in National Geographic, “Like country fairs, these great gatherings enlivened religious centers up and down the Nile. Pilgrims arrived by the hundreds of thousands and setup camp. Music and dancing filled the processional rite. Merchants sold food, drink and souvenirs. Priests became salesmen, offering wrapped mummies, as well as more elaborate ones for people who cold spend more — or thought they should. With incense swirling all around, the faithful ended their journey by delivering their chosen mummy to the temple with a prayer.”

The key annual event occurred in midsummer, and it involved not only the sun but also the bright star Sirius (which they equated with the astral god Sothis). Every spring Sirius disappears for several weeks , hidden by the sun’s glare. The New Year began when Sirius first became visible again in the predawn sky, heralding the flooding of the Nile.

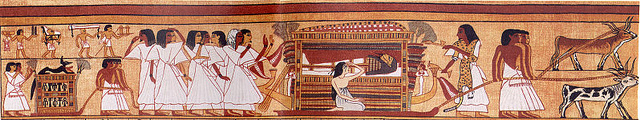

The Apis bull was one of the most revered animals in all of ancient Egypt. A.R. Williams wrote in National Geographic, “On the bull’s burial day, city residents surged into the streets to observe this occasion of national mourning. Wailing and tearing at their hair, they crowded the route at the catacomb now known as Serapeum in the desert necropolis of Saqqara. In a procession, priest temple, singers, and exalted officials delivered the mummy to the network of vaulted galleries carved into the bedrock of limestone. There among the long corridors of previous burials, they interred the mummy in a massive wooden or granite sarcophagus.”

The great festivals of ancient Egypt were similar in character, with the chief feature being a representation of some important event in the history of the god whose day was celebrated. In the Middle Kingdom, during the festival of Osiris of Abydos, the former battles of Osiris were represented; the “enemies of Osiris were beaten,"' and this god was then carried in procession to his tomb in the cemetery of Abydos, and buried. Afterwards there was a representation of “that day of the great fight," on which “all his enemies “were beaten at the place “Nedyt." In the festival of 'Epuat, the god of the dead, celebrated at Aysut, must have been very similar; he was also “conducted by a procession to his tomb," which was situated in the necropolis there." Indications of this kind are frequent, especially in the later texts. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Opet Festival

The Opet Festival in Thebes was held annually during the season of Nile flooding. It celebrated the annual reunion of the Thebean Triad: the great god Amum, his wife Mut and their son Khonsu. Details of the ceremony are carved in a relief in the processionary colonnade in Luxor Temple.

The ceremony may be been developed by Queen Hatshepsut. Opet means "southern sanctuary," a reference to Luxor Temple, the southern temple in Thebes. The Opet Festival began on the nineteenth day of the second month of the flood (the end of August). Earlier versions of the festival lasted 11 days. By the 18th dynasty (1550-1298 B.C.) the festival was the main event on the Egyptian calendar. In Ramses II's time it continued for 27 days. The festival itself may have lasted into the Roman era.

John Darnell of Yale University wrote: “The annual Opet Festival, during which the bark of Amun—and ultimately those of Mut, Khons, and the king as well—journeyed from Karnak to Luxor, became a central religious celebration of ancient Thebes during the 18th Dynasty. The rituals of the Opet Festival celebrated the sacred marriage of Amun—with whom the king merged—and Mut, resulting in the proper transmission of the royal ka and thus ensuring the maintenance of kingship. [Source: John Darnell, Yale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Opet Festival, eponymous celebration of the month Paophi (second month of the Akhet season), was an annual event at the time of its earliest attestation during the reign of Hatshepsut . Opet began on II Akhet 15 under Thutmose III and lasted 11 days; by the beginning of the reign of Ramesses III, the festival stretched over 24 days, perhaps with three days added to the conclusion of the festival by the end of his reign (Grandet suggests a 24 day observance at Medinet Habu, with 27 days of festivities on the east bank). The eve of Opet was also observed , and a Festival of Amun that Occurs after the Opet Festival is also known. The final day of the festival occurred on III Akhet 2 during Piye’s visit to Thebes. The festival appears to have continued into the Roman Period, and echoes thereof may have survived in Coptic and Islamic celebrations as well.

See Separate Articles: OPET FESTIVAL OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Festival Honoring Sokar and Orisis

Festivals for the god Sokar are known to have taken since the Old Kingdom. Sokar (Sokaris, Seker) was a falcon-headed god, with a necropolis and cult-center in Memphis, where Sokar was initially venerated as patron of craftsmen, and later as a deity connected to the district of the necropolis. Sokar was also identified with Ptah and Osiris, and he is mentioned in texts as Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. In the New Kingdom, Sokar’s cult was strong. The festival of Sokar was an integral part of the Osiris festivities of the month of Khoiak. [Source; Alexandra V. Mironova, Calendars and Festivals of the Ancient Near East, St. Petersburg State University, July 14, 2020]

According to the calendar of Ramesses III from Medinet Habu, the festival of Sokar took place on the 26 day of Koiak. On its eve, the 25th, during the night ‘festival of two goddesses’ (ntryt), Egyptians made necklaces of five onions and put them on their necks. Those five onions were associated with the teeth of Osiris or Horus and had a link to the rite of ‘opening of the mouth’ which was to revive the five senses of a dead person. People with bunches of onions followed the barque-hennu of Sokar in the ritual circumambulation the temple walls. Th e ceremony performed the solar path and served for magical protection from the evil forces. In addition to that, worshippers, perhaps, visited the district of the necropolis, where they made offerings of the deceased. Later, the procession head to the ‘Tent of purification’ (ibw), where funeral rites were held.

One of the rituals of the Osiris ceremony connected to the festival of Sokar was ‘plowing the soil’ (xbz-tA). It was. It meant the release of life forces of Osiris hidden in the soil in the form of seeds. In this case, Sokar acted as a god of dead soil and played the role of mediator between the death and the new birth of Osiris. Festivals of the month of Koiak were finished on the 30th day, when the ritual of setting the Djed column was fulfilled — it symbolized the complete resurrection of Osiris.

Erection of the Pillar of Djed

The feast of the “erection of the pillar Djed," at the close of the above-mentioned feast on the 30th day of month of Koiak was of great importance because it was solemnised on the morning of the royal event, The festivities began with a sacrifice offered by the king to Osiris, the “lord of eternity" at the place where the “noble pillar” was lying on the ground, the object of the festival. Ropes were placed round it, and the monarch, with the help of the royal relatives and of a priest, draws it up. The queen, “who fills the palace with love," looks on at the sacred proceedings, and her sixteen daughters make music with rattles and with the jingling sistrum, the usual instrument played by women on sacred occasions. Six singers join in a song to celebrate the god, and four priests bring in the usual tables of offerings to place them before the pillar which is now erect. . [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

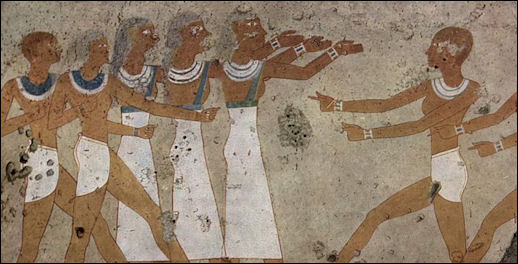

So far, we can understand the festival; it represents the joyful moment when the dead Osiris awakes to life again, when his backbone, represented in later Egyptian theology by the Djed, stands again erect. The farther ceremonies of this festival however refer to mythological events unknown to us. Four priests, with their fists raised, rush upon four others, who appear to give way, two others strike each other, one standing by says of them, “I seize Horus shining in truth." Then follows a great flogging scene, in which fifteen persons beat each other mercilessly with their sticks and fists; they are divided into several groups, two of which, according to the inscription, represent the people of the town Pe and of the town Dep. This is evidently the representation of a great mythological fight, in which were engaged the inhabitants of Pe and Dep, i.e. of the ancient city of Buto, in the north of the Delta. The ceremonies which close the sacred rite are also quite problematic: four herds of oxen and asses are seen driven by their herdsmen; in the accompanying text we are told, “four times they go round the walls on that day when the noble pillar of Dyed is erected."

We cannot conceive an Egyptian god without his house, in which he lives, in which his festivals are solemnized, and which he never leaves except on processional days. The site on which it is built is generally holy ground' i.e. a spot on which, since the memory of man, an older sanctuary of the god had stood. Even those Egyptian temples which seem most modern have usually a long history; the edifice may originally have been very insignificant, but as the prestige of the god increased, larger buildings were erected, which again, in the course of centuries, were enlarged and rebuilt in such a way that the original plan could no longer be traced. This is the history of ncarly all hgyptian temples, and explains the fact that we know so little of the temples of the Old and of the Middle Kingdom; the) have all been metamorphosed into the vast buildings of the New Kingdom.

Temple Festivals of the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods

Filip Coppens of Charles University, Prague wrote: “Egyptian temples of the Ptolemaic and Roman periods provided the setting for the dramatic performance of various cultic activities, such as festivals. This overview describes the nature, distribution (national; regional; local), and setting (within the temple; within the precinct; outside the temple domain) of these festivals, as well as our main sources of information (reliefs; inscriptions; current research) relating to them. A few representative examples, including the national feast of the “Opening of the Year,” the regional “Beautiful Feast of Behdet,” involving Dendara and Edfu, and the local celebration of the “Coronation of the Sacred Falcon” in Edfu, are covered here in greater detail to exemplify the nature and proceedings of the festivals.[Source: Filip Coppens, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Egyptian temple domains of Ptolemaic and Roman times formed the center stage for the dramatic performance of various cultic ceremonies, processions, and rituals throughout the year. The cultic activities performed in and around the temples are commonly divided, based on how frequently they took place, into two main types: daily rituals and annual festivals. These two types of ceremonies, in essence very similar and characterized by their cyclical nature (whether they took place every day or just once a year), reflect the Egyptian cyclical concept of time.

“In the daily rising and setting of the sun, the coming and going of the seasons, the phases of the moon, and the ever-recurring annual inundation of the Nile, the Egyptians observed the cyclical aspect of many natural phenomena and construed their ceremonies and festivals along a similar pattern. An ever- recurring theme in almost all festivals is their focus on fertility, birth, and the continued renewal of life. Also regularly featured in these festivals are the references to the confirmation of the existing world-order, personified by the legitimate pharaoh, and the victory over the forces of chaos.

“The essence of both the daily temple ritual and the annual festival consisted of “seeing the god” or “revealing his (i.e., the god’s) face” (mAA nTr/wn-Hr), and the “appearance” (xaw) and “coming out” (prt) of the statue of the deity. A recurring part of both the daily and the annual rites included the statue’s purification, anointment, clothing with linen, and adornment with regalia. In the daily temple ritual all activities remained confined to the main sanctuary of the temple; however, during the festivals the statues of the gods left the confines of their residence within the temple and often made a dramatic appearance in the outside world. The most typical and recurring aspect of all the festivals was indeed the appearance in procession of the statues of the gods from the sanctuary, chapels, or the temple crypts. This feature constitutes the major difference between the rather “passive” daily temple ritual and the “active” annual festivals..

“Processions with statues were reminiscent of the journey of the sun and the concept of (re)birth. Such processions often embarked from the darkness of the sanctuary or crypt, representing at times the netherworld or a tomb in which the “lifeless” statues resided, and proceeded to the sunlight outside the temple, which evoked notions of renewal and revitalization. The concept of a journey from darkness to light was also clearly reflected in the architectural layout of the temple: the statues of the gods left the sanctuary or crypt immersed in darkness, and on their way out passed through ever-broader and brighter halls, to finally appear through the gate of the pylon like the morning sun on the horizon.”

Sources on Temple Festivals of the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods

Filip Coppens of Charles University, Prague wrote: ““An important, if superficial, source of information on the numerous Egyptian festivals and processions is provided by the eleven extensive temple-calendars engraved upon the walls of the temples of Edfu, Kom Ombo, Dendara, and Esna. These calendars often provide little more than the name of the festival and the date and length of its celebration, which could last from a single day to several weeks. Occasionally, the calendars also indicate in a very general manner the main themes of the feast and at times even the location(s) where it took place, but do not allow any detailed reconstruction of the rituals carried out during the feast or their particular sequence. [Source: Filip Coppens, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Another important, although indirect, source of information regarding the temple festivals comprises several of the decrees that resulted from the annual priestly synods at the Ptolemaic court in Alexandria. The organization of the temples and the cult, including the festivals, formed an important topic of debate during these meetings (consult Hölbl 2001: 77 - 123 for a general introduction to these decrees). Most of the feasts mentioned in the temple calendars and priestly decrees can be dated to much earlier periods in Egyptian history; nonetheless, for a significant number of festivals we possess few references from prior eras.

“Although only a fraction of the textual material on the organization of Egyptian feasts has been preserved, it has been possible to reconstruct with some degree of accuracy the actual proceedings of a very limited group of Ptolemaic and Roman festivals on the basis of a series of hymns and scenes engraved on the temple walls. This is particularly the case for the temples at Edfu, Dendara, and Esna, whose walls describe the various ritual events that took place during some of the festivals. These festivals and processions can be divided into different categories on the basis of their local setting (within the temple, and inside or outside the temple precinct) and their geographical importance or impact (national, regional and local).”

Ptolemaic-Roman-Era Festivals Held at a Single Temple

Filip Coppens of Charles University, Prague wrote: “In contrast to festivals celebrated nationwide or within a specific region, a large number of festivals were both geographically and theologically limited to a single temple and its immediate surroundings. These festivals had their own local character, often inspired by the local deities and the general nature of the temple. The proceedings of several of these feasts are known from the temples of Edfu, Dendara, and Esna. The temple precinct of Edfu was, for instance, the setting for a number of festive processions involving the falcon god Horus and often focusing on his association with the kingship of Egypt. [Source: Filip Coppens, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“The “Festival of the Coronation of the Sacred Falcon” (xaw nswt) was but one of many examples of this type of feast. It was celebrated during the first days of the month of Tybi and is depicted in detail on the inner face of the temple’s enclosure wall. The festival followed almost immediately upon the feasts surrounding the internment and resurrection of the god Osiris, in his role as ruler of Egypt and father of Horus, at the end of the month of Khoiak. On the first day of the fifth month of the year, Horus, as the son and legitimate heir of Osiris, assumed the kingship over the two lands. The annual Festival of the Coronation of the Sacred Falcon can be seen as a re-enactment of both Horus and the ruling pharaoh taking their rightful place upon the throne of Egypt. The main events of this festival consisted of a series of processions within the temple precinct. The main stages of the feast included: a procession of the falcon-headed statue of Horus from the sanctuary to the “Temple of the Sacred Falcon”, located in front of the main temple; the election of a sacred falcon, reared within the temple precinct, as the heir of the god; the display of this falcon (from the platform between the two wings of the pylon) to the crowd of people gathered in front of the temple; the falcon’s coronation in the temple; and, finally, a festive meal in the “Temple of the Sacred Falcon”. Another important festival in the temple of Edfu of which more than the name has been preserved is the “Festival of Victory” (Hb qnt). Depicted on the interior of the enclosure wall.

“The temple of Esna provided the setting of a series of local festivals celebrated throughout the year, described in detail on the columns of its pronaos. The most important of these festivals took place on the first day of Phamenoth and was a combination of the local festival of the “Installation of the Potter’s Wheel,” a feast of local deity Khnum, and the Memphite festival of “Lifting up the Sky,” in honor of the god Ptah. Other important feasts that took place in and around the temple of Esna were the celebrations surrounding the “Arrival of Neith in Sais” and the “Festival of the Victory of Khnum” in the month of Epiphi. One of the best-known local festivals celebrated in Dendara was the “Festival of Intoxication” (Hb tx). The feast, described in detail on the walls of the pronaos, was celebrated in the month of Thoth and focused on the return of “the raging goddess from the South” and her enthronement.

“Other local festivities, similar to the ones mentioned above, took place in temples throughout Egypt, but very little is known of the nature and procedures of most of these feasts. A singular concept, however, appears to have been at the core of the numerous festivals celebrated throughout the year in Ptolemaic and Roman temples: it brought the statues of the gods in procession out of the confines of their residence in the temple, and through the performance of a series of ritual activities aimed to secure an ever-continuing renewal of life, fertility, and the established world-order. Concomitantly, the festivals often provided a unique and undoubtedly dramatic opportunity for the local populace to come into contact with their deities.”

Ancient Egyptian Funerary and Festival Rites That Live On in Coptic Christianity

Saphinaz-Amal Naguib of the University of Oslo wrote: “Coptic funerary rituals in today’s Egypt show many analogies to well-documented ancient Egyptian religious practices. Animal sacrifice, for example, is performed at the doorstep of the main entrance of the house when the coffin is taken out, on the same day at the cemetery, at the end of the mourning period, and periodically before the visits to the dead. The meat is distributed to the poor. However, due to various factors, these rituals have almost disappeared from large towns and cities. Visits to the dead, offerings of food and flowers, and libations at the cemetery are other reminders of Pharaonic Egypt. [Source: Saphinaz-Amal Naguib, University of Oslo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Copts go to the cemetery on fixed dates—specifically, the third day after death, after the rituals of “taking away the mattings” and “delivering the soul of the dead” have been carried out, then on the seventh, fifteenth, and fortieth day after death. Other periodic visits to the dead take place on the Coptic New Year (cayd el-nayruuz), on Nativity (cayd el-miilaad), on the Day of Immersion (yawm el-ghitaas), on Palm Sunday (‘ahad el-sacaf), during Pentecost (el-khamsiin or cayd el-cansara), and during pilgrimages and mulids. It is especially women who carry out these visits, or tuluuc (more commonly known as talca). Their attitudes resonate with those attributed to the goddesses Isis and Nephthys. Like them, they cry for the dead, lament over the corpse, bring offerings of food and flowers, and make libations of water.

“Coptic pilgrimages and mulids have gone through various developments giving way to innovations and hybridization. The term “mulid” (Arabic: mawlid, pl. mawaalid) stems from the root wld, meaning birth. It designates the birthday of a saint. More exactly, it marks the anniversary of the saint’s martyrdom or death and thereby her or his “rebirth.” By extension, mulid denotes the festivities held around the shrine of the saint, who is a center of pilgrimage. The shrine locality attracts fairs with all their various stalls and games. Mulids, whether Coptic or Muslim, pertain to popular religion and have been frowned upon by both religious and governmental authorities, which blame them for re-enacting pagan rituals, encouraging sexual licentiousness, and providing the grounds for the consumption of drugs. So much so that the term “mulid” signifies rowdiness and anarchy. Nevertheless, mulids are popular among people from different social backgrounds and until recently Copts and Muslims used to take part in each other’s mulids. Some mulids are recent creations, but the majority have a long history exemplifying the significance of a given site as a consecrated sacred space and bringing forth the descriptions of festivals dating back to the Pharaonic Period. Some saints and martyrs may have incorporated the characteristics of older local deities, but this is an opinion open to controversy.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024