HANDBOOKS FOR BABYLONIAN PRAYERS AND INCANTATIONS

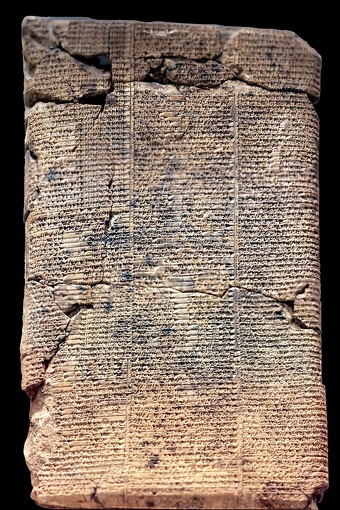

There are numerous prayers and incantations in Mesopotamian literature, usually recited by incantation-priests (ašipu). There were so many there were handbooks for them. Among the better known prayers are Utukke limnuti, ("The Evil Demons"), against demons of diseases; Bit rimki, ("The Bath House") containing ritual and incantations for purifying the king by means of lustrations; the series "Mouthwashing"; and the series Maqlu and Šurpu, devoted to the burning of witches in effigy and other white magic; and many more. The making of handbooks for these prayers began at the very beginning of writing with the making of sign lists. [Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica]

According to Encyclopaedia Judaica Individual prayers were sorted under the incantation priest: Prayers, with hymns to gods as their introductory part, developed into penitential psalms and prayers classed as incantations.To a large extent treatment of illness that was considered to be caused by evil demons was the task of the ašipu, who thus overlaps in function with the physician or asu, who worked mainly with medicaments of various kinds. It is often difficult to distinguish between his handbooks and those of the ašipu.

Laments, including laments for great public disasters, were read by the kal- (Sumerian gala) or "elegist." Laments tended to grow in length and to become more and more repetitious. They also tended to be held in more general terms and lost the close connection with identifiable historical events which characterized the older laments for destroyed cities…

There were even handbooks for omens. Omens were an Akkadian genre in Old-Babylonian times. In the following centuries the collections of omens, their systematization, and the systematic extension of possible ominous data, grew. The handbooks for the use of the barû, the "seer," were numerous. There were series dealing with omens from the shape of the liver of sacrificial animals, from dreams, from monstrous births, from ominous happenings of all kinds in city and country, astronomical omens, omens from wind and weather, and so on.

See Separate Article: MESOPOTAMIAN HYMNS, SONGS AND LAMENTS africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Sumerian Hymns and Prayers to God Nin-Ib: From the Temple Library at Nippur”

by Hugo Radau (2022) Amazon.com;

“Sumerian Hymns from Cuneiform Texts in the British Museum: Transliteration, Translation and Commentary” by Frederick Augustus Vanderburgh (1908) Amazon.com;

“Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer” by Diane Wolkstein (1983) Amazon.com;

“Kesh Temple Hymn” Music Amazon.com;

“Before the Muses”, An Anthology of Akkadian Literature, by Benjamin R Foster (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Library of Ancient Wisdom: Mesopotamia and the Making of History” by Laura Selena Wisnom (2025) Amazon.com;

“From Distant Days: Myths, Tales, and Poetry of Ancient Mesopotamia” by Benjamin R Foster (1995) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion” by Thorkild Jacobsen (1976) Amazon.com;

“Anunnaki Gods: The Sumerian Religion” by Joshua Free Amazon.com;

“A Handbook of Ancient Religions” by John R. Hinnells (2007) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary” by Jeremy Black (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture” by Francesca Rochberg Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography” by Wayne Horowitz (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Social World of the Babylonian Priest” by Bastian Still (2019) Amazon.com

Eclipse Rituals and Prayers in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said:“As we have seen, neither the cause or the nature of an eclipse was understood until a very late period, and, accordingly, the term “darkening” was applied indiscriminately to any phenomenon that temporarily obscured the moon. At the end of each month, therefore, the king proceeded to the sanctuary to take part in a ritual that must have had the same sombre character as the “lamentation” cult. In a collection of prayers, technically known as “Prayers for the Lifting Up of the Hand,” i.e., prayers of imploration, we have an example of a prayer recited on the disappearance of the moon at the end of the month, to which an allusion to an eclipse is added. The addition illustrates the association of ideas between the disappearance of the moon and a genuine eclipse. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“One suggested the other, and we gain the impression that the belief prevailed that unless one succeeded in pacifying the gods at the end of the month, an eclipse would soon follow. It was a belief hard to disprove; if no eclipse took place, the conclusion followed that the gods had been pacified. The prayer reads thus:

“O Sin, O Nannar, mighty one . . .

O Sin, unparalleled, illuminator of the darkness!

Granting light to the people of all lands,

Guiding aright the black-headed people.

Bright is thy light, in the heavens thou art exalted!

Brilliant is thy torch, like fire burning,

Thy brightness fills the wide earth.

The joy [?] of mankind is increased at thy appearance.

O lofty one of the heavens, whose course no one can fathom! Supreme is thy light like Shamash, thy first-born.

Before thee the great gods prostrate themselves,

The oracle of all lands is entrusted to thee.

The great gods beseech thee to give counsel!

Assembled, they stand in submission to thee!

O Sin, glorious one of E-Kur, they beseech thee that thou mayest render a decision!

The day of disappearance is the day of the proclaiming the decision of the great gods !

The thirtieth day is thy holy day, a day of appeal to thy divinity.

In the evil hour of an eclipse of the moon in such and such a month and on such and such a day.

Against the evil omens and the evil unfavourable signs which threaten my palace and my land.

“Besides the beginning and end of the month, the middle of the month was fraught with significance. Experience must have taught the priests and the people that a genuine eclipse of the moon could take place only at this period, when the moon appears to be taking a “rest” for a few days—remaining apparently unchanged. The middle of the month was therefore designated as shabbatum, conveying the idea of “resting.” The term corresponds to the Hebrew Shabbath or Shabbathon, which among the Hebrews was applied originally to the four phases of the moon, and then to a regular interval of seven days, without reference to the moon’s phases, and thus became the technical term for the weekly “day of rest.” In a previous lecture, we dwelt on the importance attached to the appearance of the full-moon.

“An appearance too early or somewhat belated augured a misfortune,—defeat in war, bad crops, insufficient flooding of the canals, or death. Rejoicing therefore followed the appearance of the full-moon at the expected time; and joy was multiplied when the danger of an eclipse was passed. This Babylonian “Sabbath” was, therefore, appropriately designated as “a day of pacification” when the gods appeared to be at peace with the world, smiling on the fields and gracious toward mankind.

“Among the collections of hymns to Sin there are several that bear the impress of having been composed for the celebration of the full-moon:

“O Sin, resplendent god, light of the skies, son of Enlil, shining one of E-Kur!

With universal sway thou rulest all lands! thy throne is placed in the lofty heavens!

Clothed with a superb garment, crowned with the tiara of ruler-ship, full grown in glory!

Sin is sovereign—his light is the guide of mankind, a glorious ruler,

Of unchangeable command, whose mind no god can fathom.

O Sin, at thy appearance the gods assemble, all the kings prostrate themselves.

Nannar, Sin . . . thou comest forth as a brilliant dark-red stone.

. . . as lapis lazuli. At the brilliancy of Sin the stars rejoice, the night is filled with joy.

Sin dwells in the midst of the resplendent heavens, Sin, the faithful beloved son.

Exalted ruler, first-born of Enlil . . .

Light of heaven, lord of the lands . . .

His word is merciful in Eridu . . .

Thou hast established Ur as thy dwelling[?].

“The sun, as well as the moon, was celebrated in hymns, and there can be little doubt that, in the many localities of sun-worship, both at his rising and at his setting, the priests daily chanted those hymns, accompanied by offerings and by a more or less elaborate ritual.”

New Moon Rituals in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said:The complement to the day of disappearance of the moon, elsewhere called “a day of distress,” is the new-moon day, when, amidst exclamations of joy, the return of the moon is hailed as its release from captivity. A prayer for this occasion—to be recited at night—is attached to the above text and reads as follows:

“O god of the new-moon, unrivalled in might, whose counsel no one can grasp,

I have poured for thee a pure libation of the night, I have offered to thee a pure drink.

I bow down to thee, I stand before thee, I seek thee!

Direct thoughts of favour and justice towards me!

That my god and my goddess who since many days have been angry towards me,

May be reconciled in right and justice, that my path may be fortunate, my road straight!

And that he may send Zakar, the god of dreams, in the middle of the night to release my sins!

May I hear that thou hast taken away my iniquity.

That for all times I may celebrate thy worship!

[Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

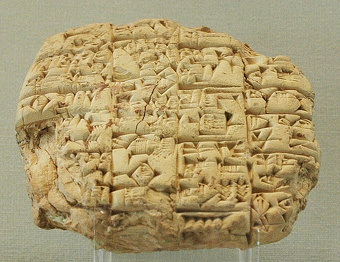

“We have an interesting proof that this new-moon prayer was actually used on the occasion of the appearance of the new-moon. A tablet has been found at Sippar, containing this very prayer, put into the mouth of Shamash-shumukin (the brother of King Ashurbanapal) who, by appointment of his brother, ruled over Babylonia for twenty years (648-628 B.C.). Attached to this prayer are directions for the accompanying ritual, which includes an offering of grain, dates, and meal, of binu wood, butter, cream, and wine.

“To this day the Arabs greet the new-moon with shouts of joy, and the Jewish ritual prescribes a special service for the occasion which includes the recital of psalms of “joy.” This joy on the reappearance of the moon is well expressed in various “Sumerian” hymns, originating with the moon-cult at Ur. They have all the marks of having been chanted by the priests when the first crescent was seen in the sky. The crescent is compared to a bark, in which the moon-god sails through the heavens. In one of these chants we read:

Self-created, glorious one, in the resplendent bark of heaven!

Father Nannar, lord of Ur!

Father Nannar, lord of E-Kishirgal !

Father Nannar, lord of the new-moon!

Lord of Ur, first-born son of Enlil!

As thou sailest along, as thou sailest along!

Before thy father, before Enlil in thy sovereign glory!

Father Nannar, in thy passing on high, in thy sovereign glory!

O bark, sailing on high along the heaven in thy sovereign glory!

Father Nannar, as thou sailest along the resplendent road

Father Nannar, when, like a bark on the floods, thou sailest along!

Thou, when thou sailest along, thou, when thou sailest along!

Thou when thou risest, thou when thou sailest along!

In thy rising at the completion of the course, as thou sailest along!

Father Nannar, when like a cow thou takest care of the calves !

Thy father looks on thee with a joyous eye—as thou takest care!

Come! glory to the king of splendour, glory to the king who comes forth!

Enlil has entrusted a sceptre to thy hand for all times,

When over Ur in the resplendent bark thou mountest.

“In this somewhat monotonous manner, and evidently arranged for responsive chanting, the hymn continues. The keynote is that of rejoicing at the release of the new-moon, once more sailing along the heavens, which it is hoped augurs well also for relief from anxiety on earth.”

Sumero-Akkadian Prayer to Every God

Mircea Eliade of the University of Chicago wrote: This Sumero-Akkadian prayer to Every God “is, in effect, a general prayer, asking any god for pardon for any transgression. The writer, in his suffering, admits that he may have broken some divine rule. But he does not know either what he has done or what god he has offended. Furthermore, he claims that the whole human race is ignorant of the divine will and thus is perpetually committing sin. The gods, therefore, should have mercy and remove his transgressions. [Source: Eliade Site]

May the fury of my lord's heart be quieted toward me.

May the god who is not known be quieted toward me;

May the goddess who is not known be quieted toward me.

May the god whom I know or do not know be quieted toward me;

May the goddess whom I know or do not know be quieted toward me,

May the heart of my god be quieted toward me;

May the heart of my goddess be quieted toward me.

May my god and goddess be quieted toward me.

May the god who has become angry with me be quieted toward me,

May the goddess who has become angry with me be quieted toward me.

(lines I 1- 1 8 cannot be restored with certainty)

in ignorance I have eaten that forbidden by my god;

in ignorance I have set foot on that prohibited by my goddess.

0 Lord, my transgressions are many; great are my sins.

0 my god, (my) transgressions are many; great are (my) sins.

my goddess, (my) transgressions are many; great are (my) sins.

O god whom I know or do not know, (my) transgressions are many;

great are (my) sins,

O goddess whom I know or do not know, (my) transgressions are many;

great are (my) sins;

The transgression which I have committed, indeed I do not know;

The sin which I have done, indeed I do not know.

The forbidden thing which I have eaten, indeed I do not know;

The prohibited (place) on which I have set foot, indeed I do not know;

The lord in the anger of his heart looked at me;

The god in the rage of his heart confronted me;

When the goddess was angry with me, she made me become ill.

The god whom I know or do not know has oppressed me;

The goddess whom I know or do not know has placed suffering upon me.

Although I am constantly looking for help, no one takes me by the hand;

When I weep they do not come to my side.

I utter laments, but no one hears me;

I am troubled; I am overwhelmed, I can not see.

O my god, merciful one, I address to thee the prayer, 'Ever incline to

me';

I kiss the feet of my goddess, I crawl before thee.

(lines 41-9 are mostly broken and cannot be restored with certainty)

How long, 0 my goddess, whom I know or do not know, eye thy hostile

heart will be quieted?

Man is dumb; he knows nothing;

Mankind, everyone that exists-what does he know?

Whether he is committing sin or doing good, he does not even know.

0 my lord, do not cast thy servant down;

He is plunged into the waters of a swamp, take him by the hand.

The sin which I have done, turn into goodness;

The transgression which I have committed, let the wind carry away;

My many misdeeds strip off like a garment.

0 my god, (my) transgressions are seven times seven; remove my

transgressions,

O my goddess, (my)transgressions are seven times seven; remove my

transgressions;

O god whom I know or do not know, (my) transgressions are seven times seven;

remove my transgressions;

O goddess whom I know or do not know, (my) transgressions are seven times

seven; remove my transgressions.

Remove my transgressions (and) I will sing thy praise.

May thy heart, like the heart of a real mother, be quieted toward me;

Like a real mother (and) a real father may it be quieted toward me.

[Source: Translation by Ferris J. Stephens, in Ancient Near Eastern Texts (Princeton, 1950), PP. 391-2; reprinted in Isaac Mendelsohn (ed.), Religions of the Ancient Near East, Library of Religion paperbook series (New York, 1955 X PP. 175-.7)]

Penitential Prayer to God

Ishtar Descent into the Underworld

This “Penitential Prayer to Every God” was found on a tablet which dates from the mid-seventh century B.C.. The original prayer is from Sumer and probably dates from somewhat earlier. [Source: "Penitential Psalms," Robert F. Harper, trans., in “Assyrian and Babylonian Literature,” R. F. Harper, ed. (New York, 1901). Reprinted in: Eugen Weber, ed., The Western Tradition, Vol I: From the Ancient World to Louis XIV. Fifth Ed., (Lexington, MA; D.C. Heath,1995) pp. 38 and 39, Then Again]

May the wrath of the heart of my god be pacified!

May the god who is unknown to me be pacified!

May the goddess who is unknown to me be pacified!

May the known and unknown god be pacified!

May the known and unknown goddess be pacified!

The sin which I have committed I know not.

The misdeed which I have committed I know not.

A gracious name may my god announce!

A gracious name may my goddess announce!

A gracious name may my known and unknown god announce!

A gracious name may my known and unknown goddess announce!

Pure food have I not eaten,

Clear water have I not drunk.

An offense against my god I have unwittingly committed.

A transgression against my goddess I have unwittingly done.

0 Lord, my sins are many, great are my iniquities!

My god, my sins are many, great are my iniquities! . . .

The sin, which I have committed, I know not.

The iniquity, which I have done, I know not.

The offense, which I have committed, I know not.

The transgression I have done, I know not.

The lord, in the anger of his heart, hath looked upon me.

The god, in the wrath of his heart, hath visited me.

The goddess hath become angry with me, and hath grievously stricken me.

The known or unknown god hath straitened me.

The known or unknown goddess hath brought affliction upon me.

I sought for help, but no one taketh my hand.

I wept, but no one came to my side.

I lamented, but no one hearkens to me.

I am afflicted, I am overcome, I cannot look up.

Unto my merciful god I turn, I make supplication.

I kiss the feet of my goddess and [crawl before her] . . .

How tong, my god . . .

How long, my goddess, until thy face be turned toward me?

How long, known and unknown god, until the anger of thy heart be pacified?

How long, known and unknown goddess, until thy unfriendly heart be pacified?

Mankind is perverted and has no judgment.

Of all men who are alive, who knows anything?

They do not know whether they do good or evil.

0 lord, do not cast aside thy servant!

He is cast into the mire; take his hand.

The sin which I have sinned, turn to mercy!

The iniquity which I have committed, let the wind carry away.

My many transgressions tear off like a garment!

My god, my sins are seven times seven; forgive my sins!

My goddess, my sins are seven times seven; forgive my sins!

Known and unknown god, my sins are seven times seven; forgive my sins.

To Ishtar, Begetress of All: Babylonian Prayer, c. 1600 B.C.

“To Ishtar, Begetress of All” (1600 B.C.) goes:

1. O fulfiller of the commands of Bel..........

Mother of the gods, fulfiller of the commands of Bel

You who brings forth verdure, you O lady of mankind, —

5. Begetress of all, who makes all offspring thrive

Mother Ishtar, whose might no god approaches,

Majestic lady, whose commands are powerful

A request I will proffer, which — may it bring good to me!

O lady, from my childhood I have been exceedingly hemmed in by trouble!

“10. Food I did not eat, I was bathed in tears!

Water I did not quaff, tears were my drink!

My heart is not glad, my soul is not cheerful;

....................I do not walk like a man.

15. ...........painfully I wail!

My sighs are many, my sickness is great!

O my lady, teach me what to do, appoint me a resting-place!

My sin forgive, lift up my countenance!

.......................................................

“20. My god, who is lord of prayer, — -may he present my prayer to you!

My goddess, who is mistress of supplication, — may she present my prayer to you!

God of the deluge, lord of Harsaga, — may he present my prayer to you!

The god of pity, the lord of the fields, — may he present my prayer to you!

God of heaven and earth, the lord of Eridu, — may he present my prayer to you!

“21. The mother of the great water, the dwelling of Damkina, —

may she present my prayer to you!

Marduk, lord of Babylon, — may he present my prayer to you!

His spouse, the exalted offspring of heaven and earth, —

may she present my prayer to you!

The exalted servant, the god who announces the good name, —

may he present my prayer to you!

“22. The bride, the first-born of Ninib, — may she present my prayer to you!

The lady who checks hostile speech, — may she present my prayer to you!

The great, exalted one, my lady Nana, — may she present my prayer to you!

[Source: George A. Barton, “Archaeology and the Bible”,” 3rd Ed., (Philadelphia: American Sunday School, 1920), pp. 398-401]

To Ishtar, He Raises to You a Wail: Babylonian Prayer

“To Ishtar, He Raises to You a Wail” (1600 B.C.) reads:

“1. ...........He raises to you a wail;

....................He raises to you a wail

On account of his face which for tears is not raised, he raises to you a wail;

On account of his feet on which fetters are laid, he raises to you a wail;

“5. On account of his hand, which is powerless through oppression, he raises to you a wail;

On account of his breast, which wheezes like a bellows, he raises to you a wail;

O lady, in sadness of heart I raise to you my piteous cry, "How long?"

O lady, to your servant — speak pardon to him, let your heart be appeased!

To your servant who suffers pain — favor grant him!

“10. Turn your gaze upon him, receive his entreaty!

To your servant with whom you are angry — be favorable unto him!

O lady, my hands are bound, I turn to you!

For the sake of the exalted warrior, Shamash, your beloved husband,

take away my bonds!

“15. Through a long life let me walk before you!

My god brings before you a lamentation, let your heart be appeased!

My goddess utters to you a prayer, let your anger be quieted!

The exalted warrior, Anu, your beloved spouse, — may he present my prayer to you!

Shamash, god of justice, may he present my prayer to you!

“20. .............the exalted servant, — may he present my prayer to you!

..........the mighty one of Ebarbar, — may he present my tears to you!

"Your eye turn truly to me," may he say to you!

"Your face turn truly to me," may he say to you!

"Let your heart be at rest", may he say to you!

“25. Let your anger be pacified", may he say to you!

Your heart like the heart of a mother who has brought forth, may it rejoice!

Like a father who has begotten a child, may it be glad!

[Source: George A. Barton, “Archaeology and the Bible”,” 3rd Ed., (Philadelphia: American Sunday School, 1920), pp. 398-401]

To Nanna, Lord of the Moon: Babylonian Prayer

“To Nanna, Lord of the Moon” (1600 B.C.) reads:

“1. O brilliant barque of the heavens, ruler in your own right,

Father Nanna, Lord of Ur,

Father Nanna Lord of Ekishshirgal,

Father Nanna, Lord of the brilliant rising,

“5. O Lord, Nanna, firstborn son of Bel,

You stand, you stand

Before your father Bel. You are ruler,

Father Nanna; you are ruler, you are guide.

O barque, when standing in the midst of heaven, you are ruler.

“10. Father Nanna, you yourself ride to the brilliant temple.

Father Nanna, when, like a ship, you go in the midst of the deep,

You got, you go, you go,

You go, you shine anew, you go,

You shine anew, you live again, you go.

“15. Father Nanna, the herd you restore.

When your father looks on you with joy, he commands your waxing;

Then with the glory of a king brilliantly you rise.

Bel a scepter for distant days for your hands has completed.

In Ur as the brilliant barque you ride,

“20. As the Lord, Nudimmud, you are established;

In Ur as the brilliant boat you ride.

........................................

. . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . .. . . .. .. .

The river of Bel Nanna fills with water.

“21. The brilliant river Nanna fills with water.

The river Diglat [Tigris] Nanna fills with water.

The brilliance of the Purattu [Euphrates] Nanna fills with water.

The canal with its gate Lukhe, Nanna fills with water.

The great marsh and the little marsh Nanna fills with water.

[Source: George A. Barton, “Archaeology and the Bible”,” 3rd Ed., (Philadelphia: American Sunday School, 1920), pp. 398-401]

To Bel, Lord of Wisdom: Babylonian Prayer

“To Bel, Lord of Wisdom” (1600 B.C.) goes:

1. O Lord of wisdom ruler...............in your own right,

O Bel, Lord of wisdom.............ruler in your own right,

O father Bel, Lord of the lands,

O father Bel, Lord of truthful speech,

“5. O father Bel, shepherd of the Sang-Ngiga [black-headed ones, or Babylonians],

O father Bel, who yourself opens the eyes,

O father Bel, the warrior, prince among soldiers,

O father Bel, supreme power of the land,

Bull of the corral, warrior who leads captive all the land.

“10. O Bel, proprietor of the broad land,

Lord of creation, you are chief of the land,

The Lord whose shining oil is food for an extensive offspring,

The Lord whose edicts bind together the city,

The edict of whose dwelling place strikes down the great prince

“15. From the land of the rising to the land of the setting sun.

O mountain, Lord of life, you are indeed Lord!

O Bel of the lands, Lord of life you yourself are Lord of life.

O mighty one, terrible one of heaven, you are guardian indeed!

O Bel, you are Lord of the gods indeed!

“20. You are father, Bel, who cause the plants of the gardens to grow!

O Bel, your great glory may they fear!

The birds of heaven and the fish of the deep are filled with fear of you.

O father Bel, in great strength you go, prince of life, shepherd of the stars!

O Lord, the secret of production you open, the feast of fatness establish, to work you call!

25. Father Bel, faithful prince, mighty prince, you create the strength of life!

[Source: George A. Barton, “Archaeology and the Bible”,” 3rd Ed., (Philadelphia: American Sunday School, 1920), pp. 398-401]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024