Home | Category: Religion / Life, Families, Women / Literature

MESOPOTAMIAN HYMNS AND LOVE SONGS

Many of the myths and stories about Mesopotamia deities are written in verse and were meant to be accompanied with musical instruments. Some of the hymns embodied in them, as well as the incantations and magical ceremonies, were doubtless familiar to the people or derived from current traditions and stories known to everyone. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

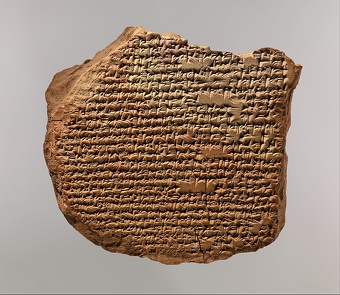

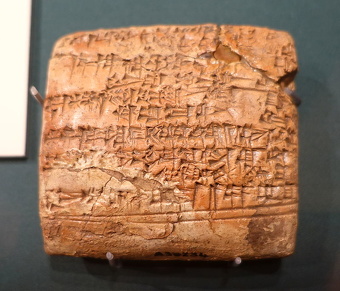

The early works in which the hymns were collected and procured, and which has been compared with the Veda of India, was at once the Bible and the Prayer-book of Chaldea. The hymns were in Sumerian, which thus became a sacred language, and any mistake in the recitation of them was held to be fatal to the validity of a religious rite. Not only, therefore, were the hymns provided with a Semitic translation, but from time to time directions were added regarding the pronunciation of certain words.

The bulk of the hymns was of Sumerian origin, but many new hymns, chiefly in honor of the Sun-god, had been added to them in Semitic times. They were, however, written in the old language of Sumer; like Latin in the Roman Catholic Church, that alone was considered worthy of being used in the service of the gods. It was only the rubric which was allowed to be written in Semitic; the hymns and most of the prayers were in what had come to be termed “the pure” or “sacred language” of the Sumerians. Each hymn is introduced by the words “to be recited,” and ends with amanû, or “Amen.”

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: A particular group of hymns to gods deserves, however, special mention: the "processional hymns." These are hymns meant to be sung as accompaniment on the occasion of ritual processions of the gods and on ritual journeys to visit other deities in other cities. Occasionally, as in the case of the composition called "The Journey of Nanna to Nippur," they approach narrative form, describing the stages of the journey by boat and Nanna's cordial reception by Enlil in Nippur before launching into a long catalog of the blessings bestowed upon him by Enlil to take along home to Ur. Somewhat similar hymns celebrate, respectively, Inanna's and Ninurta's journeys to Eridu, and a hymn of this kind, verging on both the myth and the hymn to temples in "Enki Builds Eengurra," which tells how Enki built his temple in Eridu, then traveled by boat to Nippur, where he invited the gods to a party to celebrate the completion of his new home, and where his father Enlil spoke the praise of it. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

Love songs, of which Sumerian literature has quite a few, may perhaps also be considered hymns of praise, albeit of a special distinctive character. Some of these are put in the mouth of the divine lovers, Dumuzi and Inanna, or deal with episodes of their courtship, in some the beloved is the king, particularly Shu-Sin of the Third Dynasty of Ur. These songs praise his physical attractions and express the longing and love of the girl who sings of him. It seems not unlikely that a considerable number of these songs were the work of a poetess in the circle around Shu-Sin; one would guess the lukur priestess Kubatum.

See Separate Article: MUSIC IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Kesh Temple Hymn” Music Amazon.com;

“The Music of the Most Ancient Nations - Particularly of the Assyrians, Egyptians and Hebrews” by Carl Engel (2010) Amazon.com;

“Sumerian Hymns and Prayers to God Nin-Ib: From the Temple Library at Nippur”

by Hugo Radau (2022) Amazon.com;

“Sumerian Hymns from Cuneiform Texts in the British Museum: Transliteration, Translation and Commentary” by Frederick Augustus Vanderburgh (1908) Amazon.com;

“Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer” by Diane Wolkstein (1983) Amazon.com;

“The Exaltation of Inanna” by William W. Hallo (1968) Amazon.com;

“Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart” Poems by Enheduanna (2000) Amazon.com;

“Before the Muses”, An Anthology of Akkadian Literature, by Benjamin R Foster (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Library of Ancient Wisdom: Mesopotamia and the Making of History” by Laura Selena Wisnom (2025) Amazon.com;

“From Distant Days: Myths, Tales, and Poetry of Ancient Mesopotamia” by Benjamin R Foster (1995) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion” by Thorkild Jacobsen (1976) Amazon.com;

“Anunnaki Gods: The Sumerian Religion” by Joshua Free Amazon.com;

“A Handbook of Ancient Religions” by John R. Hinnells (2007) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary” by Jeremy Black (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture” by Francesca Rochberg Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography” by Wayne Horowitz (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Social World of the Babylonian Priest” by Bastian Still (2019) Amazon.com

Hymns to Gods

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: Praise, with its attendant effects of enhancement and expression of allegiance to persons and to values, can take descriptive as well as narrative form and becomes then hymnal rather than mythical or epic. Mesopotamian literature focused such hymnal praise particularly on three subjects: gods, temples, and kings. The resultant genres are not, however, kept rigidly apart, and sections of a hymn to a god may well be devoted to praise of his temple, just as hymning a temple generally includes praise of its divine owner. The royal hymns abound in addresses to the gods to assist and protect the king hymned. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

Among major hymns directed to gods, there is reason to mention first the great hymn to Enlil of Nippur called Enlil suraše. It tells how Enlil chose Nippur as his abode, describes its sacred character so fiercely intolerant of all evil, moves on to Enlil's temple in it, Ekur, describes the latter's rituals and sacred personnel, and then Enlil himself as the key figure in the administration of the universe, planning for the maintenance and well-being of all creatures; it ends with a brief acknowledgement also of Enlil's spouse, Ninlil, who shares his powers with him.

Another remarkable hymn is a hymn to the sun-god Utu, which praises him as maintainer of justice and equity in the universe and the last recourse of those who have no-one else to turn to. Utu's sister, Inanna, is hymned as the evening star in a hymn of ten sections. It describes her role in judging human conduct, and ends with a description of her rite of the holy marriage as performed under Iddin-Dagan of Isin with the king embodying her divine bridegroom, Dumuzi. Other hymns dealing with this rite may be considered actual cult texts. Most likely they accompanied a performance of the ritual acts, for often they furnished a running account of what is done in the rite as seen by an observer at close quarters.

A very remarkable and ancient hymn to Inanna (cos i, 518–22) was written, according to Sumerian tradition, by a daughter of king Sargon of Agade, Enheduanna, who was high priestess of the moon-god Nanna in Ur. In the hymn, she has been driven out by enemies, feels abandoned by her divine husband Nanna, and turns in her distress to Inanna, the divine protector of her father and her family — and also, at that time, holder of the kingship of the gods. The description of Inanna in this hymn is that of a goddess of rains and thunderstorms.

Other hymns to goddesses of notable literary qualities are a long hymn to the goddess Nanshe in Nina emphasizing her role as upholder of morals and ethics, a long hymn to the goddess Nininsina praising her powers to heal and to drive out demons of disease, and a hymn to the goddess Nungal in Nippur, a prison goddess with strong Netherworld affinities. The hymn to her describes in detail the features of her temple, which serves as a place of ordeal and place where she judges and imprisons evildoers. It then moves into a self-praise by the goddess in which she lists her various functions and those of her husband Birtum. Many more such hymns could be mentioned, but these may suffice as examples of the genre and of the variety of treatment it allows.

Enheduana’s Hymns

Enheduanna (circa 2354 B.C.) was the first writer whose name was recorded and the first female author. She was the daughter of King Sargon, the great leader of Akkad and the destroyer of Sumeria. He lived from about 2334 B.C. to 2279 B.C. Enheduanna's name means “ornament of heaven” Her birth name is unknown. Enheduana’s hymnal cycle is a good place to observe the concepts of personal gods and goddesses. There is some display of personal religion in in-nin-me-husa (INM), “Inanna & Ebih” [Bottéro] in which Enheduanna reveals herself once in the poem by speaking anonymously in the first person :

“I, also, would like to celebrate

the good wishes of the queen of battle,

the eldest daughter of Sin”

[INM, l. 23].

Inanna dominates the poem and speaks for herself for fifty per cent of the poem: l. 26-51, 64-111, 154-166, 168-181. In fact, she is the one to introduce the main argument of the poem- that Mt. Ebih has not shown her the proper respect and that she will teach it to fear her:

“Since it [Ebih] didn’t kiss the ground infront of me,

Nor did it sweep the dust before me with it’s beard,

I will lay my hand on this instigating country:

I will teach it to fear me!” [INM, l.29-35]

This hymn may be an allusion to a historical event commemorating one of Sargon’s triumphs over a northern region that refused to relinquish its independance [Bottéro, p.220]. It would have then served as both political and religious propaganda, promoting the unequivocal domination of Sargon’s empire and personal goddess, Inanna. Inanna is portrayed as an unrelenting, warring devastatrix, characteristic of third millenium ruler metaphors:

“I’ll bring war [to Ebih], I’ll instigate combat,

I’ll draw arrows from my quiver,

I’ll unleash the rocks from my sling in a long salute,

I’ll impale it [Ebih] with my sword” [INM l. 98-102]

The marriage of politics and religion is further underlined, when after she has successfully overtaken Ebih she installs a throne and a temple and sets up rituals unique to her cult:

“Also, I erected a temple,

Where I inaugurated important events:

I set up an unshakeable throne!

I gave out dagger and sword to...,

Tambourine and drum to homosexuals,

I changed men into women!” [INM, l.172-176]

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see The Concept Of Personal God(dess) In Enheduana's Hymns to Inanna at Anglefire, Internet Archives

See Separate Article: ENHEDUANNA — WORLD’S FIRST NAMED WRITER africame.factsanddetails.com

Hymns to Temples and Kings

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: Praise of temples looms large, as we have mentioned, in many of the hymns to gods. It may also be the main theme of a hymn. Such hymns to temples would seem to have been represented already in the Fara and Abu Salabikh materials. A particularly noteworthy example of the genre is a cycle of hymns to all the major temples in Sumer and Akkad composed by the already mentioned Enheduanna and faithfully copied in the schools for centuries afterwards. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

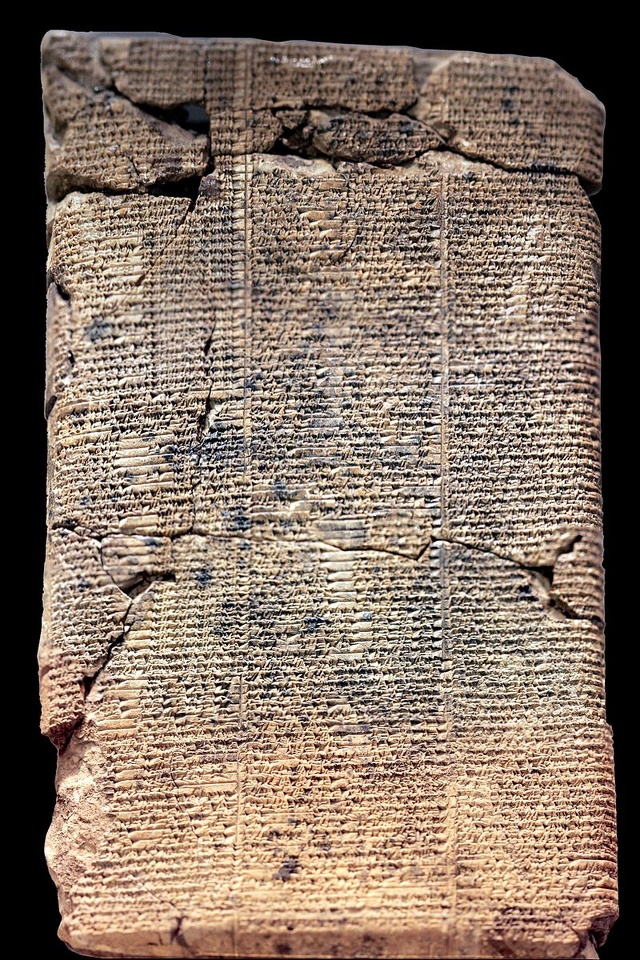

Even older, is the much copied "Hymn to the Temple of Kesh," which is already represented in the Abu Salabikh materials. The finest example of the genre is, however, a hymn which never entered the standard body of school literature: the great hymn to the temple of Ningirsu in Girsu, E-ninnu, written on the occasion of its rebuilding by Gudea. The hymn was originally written on three large clay cylinders, of which the second and third are preserved. It describes in detail the communication of Ningirsu's wishes to Gudea in a dream, the care taken to check that the god's message was correctly understood and to carry out the task correctly, the bringing of building materials from afar, the actual building process step for step, and finally the occupation of the new temple by Ningirsu, the appointment of its divine staff, and the concluding "housewarming party" for the gods.

A suitable subject for hymning was also the king, and a great many royal hymns are extant. The oldest examples of the genre deal with Ur-Namma, the first king of the Third Dynasty of Ur. A high point of productivity was reached with his successor, Shulgi, who figures in more than 20 hymnal compositions, and the genre continues to be productive through the first half of the succeeding Isin Dynasty, at which point it begins to peter out. The last example is a hymn to Abi-eshuh of the First Dynasty of Babylon. The content of the genre is varied in the extreme. Many of the hymns deal with the election of the king by the assembly of the gods, or with divine favors showered upon him. Some contain appeals to the gods on the kin's behalf, and some — the royal hymns in the narrower sense — contain a sustained praise of the king, his abilities, e.g., as warrior or as scholar, his virtues, e.g., his sense of justice and fairness, and the prosperity he brought to the country. Frequently these hymns take the form of self-praise and are put in the mouth of the king himself.

Laments and Dirges

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: Laments for Gods Lament for the dead god was a central part of the cult of most dying gods and many such laments are preserved. To the Dumuzi cult belongs the moving lament by his mother in "A Reed-Pipe — My Heart Plays a Reed-Pipe (Instrument) of Dirges for Him in the Desert" and many others. Most often there is an element of narrative, reflecting the fact that these laments were part of the ritual of going to the god's destroyed fold in the desert. The Damu laments likewise tend to alternate with narrative sections, but the lament of Aruru for her lost son, and the lament of Lisin are examples of pure laments. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

As the loss of gods and kings was mourned, so were the great public disasters: destruction of cities and their temples at the hand of enemies. The lament was intended to soothe the emotions of the bereaved god and channel them, and thus prepare the way for divine will to restoration. To the genre of lament for destroyed temples belongs what is perhaps the highest achievement of Sumerian poetry, the magnificent and deeply moving "Lament for the Destruction of Ur," which deals with the capture and destruction of the city by the Elamites and the Sua people that ended the Third Dynasty of Ur. The vivid and very detailed, but much less powerful, "Lament for Ur and Sumer" (cos i: 535–39) deals with the same event. Among later laments there is the long "Lament for Nippur and Ekur" connected with the restoration of Ekur by Ishme-Dagan, which ends with a long section in which Enlil promises to restore the temple. Other laments for Ekur and for Inanna's temple in Uruk, eanna, popular in later times, go back to the end of the Isin-Larsa period. As in the Dumuzi laments, so in the laments for temples, narrative and lyrical sections alternate, the dramatic events around the day of destruction being told in all their stark detail.

Laments for kings and heroes in non-narrative lyric form have not so far been found, but two examples of dirges for ordinary mortals succeeded in entering the standard body of literature. They were written by a certain Ludingirra, one in honor of his father, the other on occasion of his wife's death.

Public Lamentation Rituals in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “A further development of the taboo , but in a much higher direction, is represented by the public lamentation ritual, which from early days appears to have formed a part of the official cult on occasions of public distress, when the gods had manifested their displeasure by sending a pestilence, by disaster in war, by atmospheric disturbances, dealing death and destruction, or by terrifying phenomena in the heavens. We have numerous examples of such lamentations whereof the antiquity is sufficiently attested by the fact that they are written in Sumerian, though for a better understanding translations into Babylonian, either in whole or in part, were added in the copies made at a later date. The basis of these texts is likewise the notion of uncleanliness. The entire land was regarded as having become taboo through contamination of some kind, or through some offence of an especially serious character. The gods are depicted as having deserted the city and shown their anger by all manner of calamities that have been visited upon the country and its inhabitants. Atonement can be secured only by an appeal to the gods, and a feature of this atonement ritual—as we may also call this service—is abstention from food and drink. We may well suppose that on such occasions the people repaired to the temples and participated in the service, though no doubt the chief part was taken by the priests and the king. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“It was probably for these occasions that purification ceremonies (which appear to have been particularly elaborate) were prescribed for the priests, though it should be added that for all other occasions, also, the priests had to take precautions so as to be in a state of ritualist cleanliness before undertaking any service in the temples. Atonement for the priests and the king, for the former as the mediators between the gods and their worshippers, for the latter as standing nearer to the gods than the masses and in a measure, as we have seen, a god’s representative on earth, was an essential preliminary to obtaining forgiveness for the people as a whole. In the public lamentation-songs it is the general condition of distress that is emphasised, and the impression is gained that the priests send forth their appeals to the gods for forgiveness on behalf of the people in general.

“We have already had occasion to indicate the preeminent position occupied by the city of Nippur in the religious life of Babylonia. It is therefore interesting to note that the atonement and lamentation ritual worked out by the priests of this centre became the pattern which was followed in other places —such as Isin, Ur, Larsa, Sippar, Babylon, and Borsippa. The proof is furnished by examples of lamentations, bearing internal evidence of their original connection with the temple E-Kur at Nippur, but in which insertions have been made to adapt them to other centres. The laments themselves are rather monotonous in character, though the rhythmic chanting no doubt lessened the monotony and heightened their solemnity. They describe the devastation that has been wrought, repeating in the form of a litany the prayer that the gods may be appeased. Occasionally, the laments contain picturesque phrases.

“As an instance, one will perhaps be sufficient, which contains the insertions referred to, adapting the Nippur composition to Ur and Larsa.

O honoured one, return, look on thy city!

O exalted and honoured one, return, look on thy city!

O lord of lands, return, look on thy city!

O lord of the faithful word, return, look on thy city!

O Enlil, father of Sumer, return, look on thy city!

O shepherd of the dark-headed people, return, look on thy city!

O thou of self-created vision, return, look on thy city!

Strong one in directing mankind, return, look on thy city!

Giving repose to multitudes, return, look on thy city!

To thy city, Nippur, return, look on thy city!

To the brick construction of E-Kur, return, look on thy city!

To Ki-Uru, the large abode, return, look on thy city!

To Dul-Azag, the holy place, return, look on thy city!

To the interior of the royal house, return, look on thy city!

To the great gate structure, return, look on thy city!

To E-Gan-Nun-Makh, return, look on thy city!

To the temple storehouse, return, look on thy city!

To the palace storehouse, return, look on thy city!

Unto the smitten city—how long until thou returnest?

To the smitten—when wilt thou show mercy?

The city unto which grain was allotted,

Where the thirsty was satiated with drink.

Where she could say to her young husband, “my husband,”

Where she could say to the young child, “my child,”

Where the maiden could say, “my brother.”

In the city where the mother could say, “my child,”

Where the little girl could say, “my father.”

There the little ones perish, there the great perish.

In the streets where the men went about, hastening hither and thither,

Now the dogs defile her booty,

Her pillage the jackal destroys,

In her banqueting hall the wind holds revel,

Her pillaged streets are desolate.

Mesopotamia Lamentations and the Destruction of Its Cities

Morris Jastrow said: “In reading the closing lines of this litany, we are instinctively reminded of the prevailing note in the Biblical book of Lamentations, the five chapters of which represent independent compositions. These lamentation-songs still constitute, in orthodox Judaism, an integral part of the ritual for the day commemorative of the double destruction of Jerusalem —the first by Nebuchadnezzar in 586 B.C., and the second in 70 A.D., by the Romans—and, precisely as in ancient Babylonia, fasting constitutes one of the features of the day. Whether or not the second destruction actually occurred on the day commemorated is more than doubtful; and it is not even certain that the first destruction occurred on the 9th day of the 5th month. It is more likely that this day had acquired a significance as a day of fasting and lamentation, long before Jerusalem fell a prey to Babylonia, and for this reason was chosen by the Jews in commemoration of the great national catastrophe. Be this as it may, the resemblance between the Hebrew and the Babylonian “lamentation” rituals suggests a direct influence on the Hebrews; which becomes all the more plausible if it be recalled that another fast day, which in post-exilic times became for the Jews the most solemn day of the year, took its rise during the sojourn of the Jews in Babylonia. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“Destructions of cities are often mentioned in the dates attached to business documents of ancient Babylonia. We have also a series of texts in which the distress incident to national catastrophes brought about by the incursion of enemies is set forth in diction which recalls the style of the lamentation-psalms. It is interesting to note that in the' astrological omens (which formed the subject of the previous lecture) references to invasions by foreign foes are very frequent, and phrases are introduced, clearly taken from these commemorative compositions. All this points to the deep impression made upon the country by the disasters of the past, and suggests the question whether, in commemoration of these events, a certain day of fasting and lamentation may not have been yearly set aside, whereon the ancient compositions of the “Nippur” ritual were recited or sung in the temples, with an enumeration of the various occasions in the past when the gods had manifested their displeasure and wrath.

“With such a supposition, one could reasonably account for the additions in the old ritual, referring to catastrophes in Ur, Larsa, Sippar, Babylon, and so forth, instead of the mere substitution of these names for that of Nippur which would have sufficed if the purpose had been merely to recall some particular event. Lacking direct evidence of a day set apart as a general fast-day and day of penitence, humiliation, and prayer for favour and grace during the coming year, a certain measure of caution must be exercised; but we are fully justified in going so far at least as to assume that the lamentation ritual was performed in the great centres when there was an actual or impending catastrophe, and that on such occasions the dire events of the past were recalled in laments which, by virtue of the sanctity that everything connected with the cult at Nippur had acquired, were based on the “Nippur” ritual.

“The fear of divine anger runs, as an undercurrent, throughout the entire religious literature of Babylonia and Assyria. Rulers and people are always haunted by the fear lest Enlil, Sin, Shamash, Ea, Marduk, Nebo, Nergal, Ishtar, or some other deity manifest displeasure. This minor key is struck even in hymns which celebrate the kindness and mercy of the higher powers; there was a constant fear lest their mood might suddenly change. Death and sickness stood like spectres in view of all men, ready at any moment to seize their victims. Storms and inundations, however needful for the land, brought death and woe for man and beast. Enemies were constantly pressing in on one side or the other; and thus the occasions were frequent enough when the people were forced to cringe in contrition before the gods in the hope that they might soon smile with favour, and send joy into the heart of man, or else that a threatened blow might never fall.

See Lament for the Destruction of Ur Under UR: THE GREAT CITY OF SUMER AND HOMETOWN OF ABRAHAM africame.factsanddetails.com

Mesopotamia Penitential Psalms

Morris Jastrow said: “As a complement to the public lamentation ritual, we have numerous compositions in which woe is poured forth before a god or goddess, and emphasis is laid upon the consciousness of guilt. The soul is bowed down with the consciousness of some wrong committed, and even though the particular sin for which misfortune—sickness or some misadventure or trouble—has been sent is unknown to the suppliant himself, he yet feels that he must have committed some wrong to arouse such anger in the god who has struck him down. This is the significant feature in these “penitential psalms,” as they have been called, and one that raises them far above the incantation ritual, even though they assume the belief also in the power of demons and sorcerers to bring to pass the ills whereto human flesh is heir. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“To be sure, most, if not all, of these penitential psalms assume that the penitent is the king, just as most of the other classes of hymns are royal hymns; but this would appear to be due mainly to the official character of the archives from which the scribes of Ashurbanapal obtained their material. In compositions of Assyrian origin, or modified by Assyrian priests, the official character is even more pronounced, since these priests, acting directly at the command of their royal master, had him more particularly in mind. We are safe in assuming that these royal laments and confessions formed the model for those used by the priests when the lay suppliant came before them, though exactly to what extent they were used in the case of individuals, as supplementary to the incantation rites, it is impossible to say. Confession and lament are the burden of these psalms: “Many are my sins that I have committed, / May I escape this misfortune, may I be relieved from distress!” And again: “My eye is filled with tears, / On my couch I lie at night, full of sighs, /Tears and sighing have bowed me down.”

“The indications are distinct in these compositions that they formed part of a ritual, in which the officiating priest and the penitent each had his part. The priest, as mediator, enforces the appeal of the penitent:

“He weeps, overpowered he cannot restrain himself.

Thou hearest earnest lament, turn thy countenance to him!

Thou acceptest petition, look faithfully on him!

Thou receivest prayer, turn thy countenance to him!

Lord of prayer and petition, let the prayer reach thee!

Lord of petition and prayer, let the prayer reach thee!

“The appeal is here made to Enlil, Marduk, and Nebo, and closes with the refrain which is frequent in the penitential psalms:

May thy heart be at rest, thy liver be appeased!)

May thy heart like the heart of the young mother,—

Like that of the mother who has borne, and of the father who has begotten,—return to its place!

“Reference has been made to the fact that the sense of guilt in these hymns is so strong as to prompt the penitent to a confession, even when he does not know for what transgression—ritualistic or moral—he has been punished, nor what god or goddess he has offended. The penitent says in one of these psalms:

O lord my transgressions are many, great are my sins.

My god, my transgressions are many, great are my sins.

O god, whoever it be, my transgressions are many, great are my sins.

O goddess, whoever it be, my transgressions are many, great are my sins.

The transgressions I have committed, I know not.

The sin I have done, I know not.

The unclean that I have eaten, I know not.

The impure on which I have trodden, I know not...

The lord in the anger of his heart has looked at me,

The god in the rage of his heart has encompassed me.

A god, whoever it be, has distressed me,

A goddess, whoever it be, has brought woe upon me.

I sought for help, but no one took my hand,

I wept, but no one hearkened to me,

I broke forth in laments, but no one listened to me.

Full of pain, I am overpowered, and dare not look up.

To my merciful god I turn, proclaiming my sorrow.

To the goddess [whoever it be, I turn proclaiming my sorrow].

O lord, [turn thy countenance to me, accept my appeal].

O goddess, [look mercifully on me, accept my appeal].

O god [whoever it be, turn thy countenance to me, accept my appeal].

O goddess whoever it be, [look mercifully on me, accept my appeal].

How long yet, 0 my god, [before thy heart shall be pacified]?

How long yet, O my goddess, [before thy liver shall be appeased]?

O god, whoever it be, may thy angered heart return to its place!

O goddess, whoever it be, may thy angered heart return to its place!

“The higher intellectual plane reached by these compositions is also illustrated by the reflections attached to them on the weakness of human nature and the limitations of the human mind, unable to fathom the ways of the gods:

“Men are obtuse,—and no one has knowledge.

Among all who are,—who knows anything?

Whether they do evil or good,—no one has knowledge.

O lord, do not cast thy servant off!

In the deep watery morass he lies—take hold of his hand!

The sin that I have committed, change to grace!

The transgressions that I have committed,—let the wind carry off!

Tear asunder my many iniquities like a garment!

“Even more interesting are the reflections put into the mouth of an ancient—probably legendary— king of Nippur, Tabi-utul-Enlil, in a composition which combines with an elaborate and touching lament the story of an aged royal sufferer, who like Job was known for his piety, and yet was severely punished and sorely tried by painful disease. As in the book of Job, the tone of the composition is pessimistic and skeptical—at least to the extent of questioning whether any one can understand the hidden ways of the gods: “I attained (mature) life, to the limit of life I advanced. / Whithersoever I turned—evil upon evil! “This penitential psalm ends with the answer to the king’s appeal; its most striking passage is the following—one of the finest in the whole realm of Babylonian literature, and marked by a remarkably modem undertone. The king declares that he did everything to please the gods; he prayed to them; he observed the new-moon, and the festivals, and brought the gods offerings: “Prayer was my rule, sacrificing my law, / The day of worship of my god, my joy, / The day of devotion to my gods, my profit and gain.

“He instructed his people in the ways of the gods and did all in the hope of pleasing the higher powers —but apparently in vain:

“What, however, seems good to one, to a god may be displeasing.

What is spurned by oneself may find favour with a god.

Who is there that can grasp the will of the gods in heaven?

The plan of a god is full of mystery,—who can understand it?

How can mortals learn the ways of a god?

He who is still alive at evening is dead the next morning.

In an instant he is cast into grief, of a sudden he is crushed.

This moment he sings and plays,

In a twinkling he wails like a mourner.

Like opening and closing, (mankind’s) spirit changes.

If they hunger, they are like corpses.

Have they been satiated, they consider themselves a rival to their god.

If things go well, they prate of mounting to heaven.

If they are in distress, they speak of descending into Irkallu”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024