Home | Category: Hittites and Phoenicians

HITTITES AND THEIR RIVALS

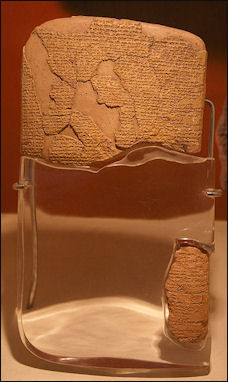

Treaty of Kadesh

between Hittites and Egyptians The Hittites founded a kingdom in Anatolia (Turkey) in the 18th century B.C., Their capital was Hattusas (Boğazköy). They controlled a powerful empire in the 15th–13th centuries B.C. and expanded east and south in the 15th century B.C. and conquered n Syria before being checked by the Egyptians. The first Hittite kingdoms, archaeologists believe, formed in central Anatolia in about 2100 B.C. The Hittites appear in the Hebrew Bible, and ancient Egyptian inscriptions record that the Hittite Empire battled the Pharaoh Ramses II in 1274 B.C. at the Battle of Kadesh — an ancient city near modern-day Homs, Syria — in one of history's earliest battles. Under attack from Assyria, the Hittite Empire disintegrated in c.1200 B.C. [Source: Live Science]

The Hittites were charioteers who wrote manuals on horsemanship. Ninth century B.C. stone reliefs show Hittite warriors in chariots. "Charioteers were the first great aggressors in human history," the historian Jack Keegan wrote. They had an easy time conquering the nomads and farmers that inhabited the region. Donkeys were their fastest animal. See Horsemen.

Rivals of ancient Egypt, the Hittites controlled an area that roughly corresponds to modern Turkey and Syria. Around 2000 B.C. the Hittites were unified under a king named Labarna. A later king pushed their domain into Mesopotamia and Syria. The empire lasted into 1650 B.C. A more powerful kingdom rose in 1450 B.C. This kingdom possessed iron.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Kingdom of the Hittites” by Trevor R. Bryce (Oxford University Press, 1998) Amazon.com;

“The Hittites and Their Contemporaries in Asia Minor” by James G. Macqueen (1975) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamian History: Sumerians, Hittites, Akkadian Empire, Assyrian Empire, Babylon” by History Hourly (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Hittites and Their World” by Billie Jean Collins (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Hattian and Hittite Civilizations” by Ekrem Akurgal (1995) Amazon.com;

“Warriors of Anatolia: A Concise History of the Hittites” by Trevor R. Bryce (2018) Amazon.com;

“Hittite Fortifications c.1650-700 BC” by Konstantin Nossov (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Hittites: Lost Civilizations” by Damien Stone (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Hittites” by Leopold Messerschmidt (1903) Amazon.com;

“Hattusili, the Hittite Prince Who Stole an Empire: Partner and Rival of Ramesses the Great” by Trevor R. Bryce (2024) Amazon.com;

"Life and Society in the Hittite World” by Trevor Bruce (Oxford University Press, 2002).

Amazon.com;

“After 1177 B.C.: The Survival of Civilizations” by Eric H. Cline (2024) Amazon.com;

“I, the Sun” Novel by Janet Morris (1983) Amazon.com;

Akkadians, Amorites and Hittites

Morris Jastrow said: Two factors exercised “a decided influence in further modifying the Sumero-Akkadian culture; one of these is the Amoritish influence, the other is a conglomeration of peoples collectively known as the Hittites. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“Hittites do not make their appearance in the Euphrates Valley until some centuries after Sargon, but since it now appears that ca. 1800 B.C. they had become strong enough to invade the district, and that a Hittite ruler actually occupied the throne of Babylonia for a short period, we are justified in carrying the beginnings of Hittite influence back to the time at least of the Ur dynasty. This conclusion is strengthened by the evidence for an early establishment of a Hittite principality in north-western Mesopotamia, known as Mitanni, which extended its sway as early at least as 2100 B.C. to Assyria proper.

“Thanks to the excavations conducted by the German expedition at Kalah-Shergat (the site of the old capital of Assyria known as Ashur), we can now trace the beginnings of Assyria several centuries further back than was possible only a few years ago. The proper names at this earliest period of Assyrian history show a marked Hittite or Mitanni influence in the district, and it is significant that Ushpia, the founder of the most famous and oldest sanctuary in Ashur, bears a Hittite name. The conclusion appears justified that Assyria began her rule as an extension of Hittite control. With a branch of the Hittites firmly established in Assyria as early as ca. 2100 B.C., we can now account for an invasion of Babylonia a few centuries later. The Hittites brought their gods with them, as did the Amorites, and, with the gods, religious conceptions peculiarly their own. Traces of Hittite influence are to be seen e.g., in the designs on the seal cylinders, as has been recently shown by Dr. Ward, who, indeed, is inclined to assign to this influence a share in the religious art, and, therefore, also in the general culture and religion, much larger than could have been suspected a decade ago.

“Who those Hittites were we do not as yet know. Probably they represent a motley group of various peoples, and they may turn out to be Aryans. It is quite certain that they originated in a mountainous district, and that they were not Semites. We should thus have a factor entering into the Babylonian-Assyrian civilisation—leaving its decided traces in the religion—which was wholly different from the two chief elements in that civilisation—the Sumerian and the Akkadian.”

Hittite-Akkadian Treaty between Mursilis and Duppi-Tessub

Preamble: These are the words of the Sun Mursilis, the great king, the king of the Hatti land, the valiant, the favorite of the Storm-god, the son of Suppiluliuma, the great king, the king of the Hatti land, the valiant. [Source: Ancient Near Eastern Texts, ed. by J. B. Pritchard (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), pp. 203-205, Internet Archive, from Creighton]

Preamble: These are the words of the Sun Mursilis, the great king, the king of the Hatti land, the valiant, the favorite of the Storm-god, the son of Suppiluliuma, the great king, the king of the Hatti land, the valiant. [Source: Ancient Near Eastern Texts, ed. by J. B. Pritchard (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), pp. 203-205, Internet Archive, from Creighton]

Historical Prologue: Aziras was the grandfather of you, Duppi-Tessub. He rebelled against my father, but submitted again to my father. When the kings of Nuhasse land and the kings of Kinza rebelled against my father, Aziras did not rebel. As he was bound by treaty, he remained bound by treaty. As my father fought against his enemies, in the same manner fought Aziras. Aziras remained loyal toward my father as his overlord as did not incite my father's anger. My father was loyal toward Aziras and his country; he did not undertake any unjust action against him or incite his or his country's anger in any way. 300 shekels of refined and first-class gold, the tribute which my father had imposed upon your father, he brought year for year; he never refused it.

When my father became god (i.e. died) and I seated myself on the throne of my father, Aziras behaved toward me just as he had behaved toward my father. It happened that the Nuhasse kings and the king of Kinza rebelled a second time against me. But Aziras, your grandfather, and DU-Tessub, your father did not take their side; they remained loyal to me as their lord. When he grew too old and could no longer go to war and fight, DU-Tessub fought against the enemy with the foot soldiers and the charioteers of the Amurru land just as he had fought with foot soldiers and charioteers against the enemy. And the Sun destroyed them.

When your father died, in accordance with your father's word I did not drop you. Since your father had mentioned to me your name with great praise, I sought after to you. To be sure, you were sick and ailing, but although you were ailing, I, the Sun, put you in the place of your father and took your brothers and sisters and the Amurru land in oath for you.

When I, the Sun, sought after you in accordance with your father's word and put you in your father's place, I took you in oath for the king of the Hatti land, the Hatti land, and for my sons and grandsons. So honor the oath of loyalty to the king and the king's kin! And I, the king, will be loyal toward you, Duppi-Tessub. When you take a wife, and when you beget an heir, he shall be king in the Amurru land likewise. And just as I shall be loyal toward you, even so shall I be loyal toward your son.

Stipulations: But you, Duppi-Tessub, remain loyal toward the king of the Hatti land, the Hatti land, my sons and my grandsons forever! The tribute which was imposed upon your grandfather and your father-they presented 300 shekels of good, refined first-class gold weighed with standard weights-you shall present it likewise. Do not turn your eyes to anyone else! Your fathers presented tribute to Egypt; you shall not do that!

With my friend you shall be friend, and with my enemy you shall be enemy. If the kings of the Hatti land is either in the Hurri land, or in the land of Egypt, or in the country of Astata, or in the country of Alse-any country contiguous to the territory of your country that is friendly with the king of the Hatti land-as the country of Mukis, the country of Halba and the country of Kinza-but turns around and becomes inimical toward the king of the Hatti land while the king of the Hatti land is on a marauding campaign-if then you, Duppi-Tessub, do not remain loyal together with your foot soldiers and your charioteers and if you do not fight wholeheartedly; or if I should send a prince or a high officer with foot soldiers and charioteers to re-enforce you, Duppi-Tessub, for the purpose of going out to maraud in another country-if then you, Duppi-Tessub, do not fight wholeheartedly that enemy with your army and your charioteers and speak as follows: "I am under an oath of loyalty, but how am I to know whether they will beat the enemy, or the enemy will beat them?"; or if you even send a man to that enemy and inform him as follows: "An army and charioteers of the Hatti land are on their way; be on your guard!"-if you do such things, you act in disregard of your oath.

Fall of the First Babylonian Empire to the Hittites and Kassarites

After Hammurabi’s death, the Babylonians were harassed by Indo-European tribes in the northern mountains. The Babylon empire came to an end when the Indo-European Hittites sacked Babylon in 1595 B.C. Around the same time the Hykos invaded Egypt and the Hurrians occupied Syria. The late second millennium B.C. has been called “the first international age.” It was a time when there was more interaction between kingdoms.

Around the second millennia B.C. the Indo Europeans tribes from north of India similar to the Aryans invaded Asia Minor. The Hittites, and later the Greeks, Romans, Celts and nearly all Europeans and North Americans descended from these tribes. They carried bronze daggers. The Hittite Empire dominated Asia Minor and parts of the Middle East from 1750 B.C. to 1200 B.C. Once regarded as a magical people, the Hittites were known for their military skill, the of development of an advanced chariot, and as one of the first cultures to smelt iron and forge it weapons and tools. They fought with spears from chariots and did not possess more advanced composite bow.

Hittite rule

After a period of increasing turmoil and internal weakness, Babylon was taken over by Kassites, an Iranian people, in about 1575 B.C. Their rule seems to have had little discernable effect on Babylon’s political structure, but the lack of written records from this period makes certainty impossible. [Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Encyclopedia.com]

The Kassites, a tribe from the Zagros mountains in present-day Iran, arrived in Babylonia and filled a vacuum left by the Hittite invasion. The Kassites, controlled Mesopotamia from 1595 to 1157 B.C. They introduced war chariots, The Kassites were defeated by the Elamites in 1157 B.C. A 300-year Middle Eastern Dark lasted from 1157 to 883 B.C. During this period the Assyrians in what is now northern Syria gained strength.

See Separate Article: BABYLON AND BABYLONIA: GEOGRAPHY AND OCCUPIERS africame.factsanddetails.com

Hittites and Egyptians

During the New Kingdom in ancient Egypt (1539 to 1075 B.C.), the Egyptian empire extended southward to the land of Punt (Somalia) and the 5th Cataract near present-day Khartoum, Sudan, and eastward across the Middle East past Palestine and Syria to the Euphrates River of Mesopotamia. The powerful Hittites and Mitanni in the north at various times were both enemies and allies. Assyria and Babylon sent tributes.

Under the Pharaoh Akhenate, who ruled for 17 years from 1353 B.C. to his death in 1336 B.C., the Egyptian kingdom was neglected and Egypt's arch enemies the Hittites began encroaching from the east. In the middle of tense period with the Hittites, when Egypt’s possessions in Syria were being threatened, Akhenaten died. A Hittite text described an Egyptian attack on Kadesh in present-day Syria during Tutankhamun’s (King Tut’s) rule (1334 to 1325 B.C.).

After Tutankhamun’s death there was a vacuum of power and major crisis to fill it. Tutankhamun’s wife Anhesanamun launched a coup and pleaded for help from the Hittites. “My husband is dead,” she wrote them. “Send me your son and I will make him king.” The Hittite prince Zannanza was sent to marry her but he was killed — presumably by an assassin — as he entered Egyptian territory.

Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic, “We know that after Tutankhamun's death, an Egyptian queen, most likely Ankhesenamun, appeals to the king of the Hittites, Egypt's principal enemies, to send a prince to marry her, because "my husband is dead, and I have no son." The Hittite king sends one of his sons, but he dies before reaching Egypt. I believe he was murdered by Horemheb, the commander in chief of Tutankhamun's armies, who eventually takes the throne for himself. But Horemheb too dies childless, leaving the throne to a fellow army commander. The new pharaoh's name was Ramses I. With him begins another dynasty, one which, under the rule of his grandson Ramses the Great, would see Egypt rise to new heights of imperial power.

Ramses the Great, also known as Ramses II, had eight wives — including his younger sister and three daughters — and numerous concubines, which included several Hittite princesses. At the Temple in Abu Simbel are also a number of dedications. Important among these is one of Ramses II's marriage to the daughter of a Hittite king. Beyond the entrance is the Great Hall of Pillars, with eight 32-foot-high pillars of Ramses defied as the God Osiris. The walls have inscriptions recording the Battle of Kadesh against the Hittites.

Marriage, Murder and Hittite-Egyptian Relations

A succession crisis near the end of the 18th Dynasty in Egypt affected the lives of Amenhotep III’s surviving family members and also sealed the fate of an Anatolian prince, Zannanza, son of the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I (r. ca. 1370–1330 B.C.). Luis Alberto Ruiz wrote in National Geographic: One sign that the Hittites had returned as major players in the region was a letter from an Egyptian queen to Suppiluliumas I. The pharaoh had recently died (scholars believe it was most likely Tutankhamun, but it could have been his father, Akhenaten). She asked him to send one of his sons in marriage. Unfortunately for Hittite-Egyptian relations, the son, when he arrived, was killed by an Egyptian faction who opposed the queen. Hittites recorded this offense in one of the “plague prayers” inscribed during the rule of Suppiluliumas’s successor, Mursilis II. The words show the central role chariots played in both the war and regional diplomacy that followed: "My father sent infantry and chariot fighters and they attacked the border territory. And, moreover, he sent (more troops); and again, they attacked. [The] men of Egypt became afraid. They came, and they asked my father outright for his son for kingship. And when they led him away, they killed him. And my father became angry, and he went into Egyptian territory, and he attacked the infantry and chariot fighters of Egypt." [Source: Luis Alberto Ruiz, National Geographic, May 1, 2020]

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Cuneiform tablets unearthed in the Hittite capital of Hattusa in modern-day Turkey called The Deeds of Suppiluliuma tell the story of the prince’s involvement in an effort at diplomacy that went disastrously awry. A vivid passage in this account of Suppiluliuma I’s reign records a panicked missive written to the king by an Egyptian royal identified as a dakhamunzu, which seems to be a rendering of the Egyptian term for the “king’s wife.” In her letter, the dakhamunzu tells Suppiluliuma I that her husband, the king, is dead and that she has no children. She needs to remarry, and suggests a mutually beneficial arrangement. “They say you have many sons: Give me one of your sons,” she writes, “to me he will be husband, but in the land of Egypt he will be king!” [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

During the reign of the pharaoh Akhenaten, Suppiluliuma I conducted a series of aggressive campaigns against Egyptian client states in Syria. The fact that Egypt and the Hittite Kingdom were engaged in a high-stakes proxy war seems to have caused Suppiluliuma I to harbor grave doubts about the offer, and he eventually dispatched a diplomatic mission to gauge the dakhamunzu’s sincerity. Only after months of considering the proposal did he eventually send his son Zannanza to Egypt to be wed and crowned pharaoh.

That delay may have been costly. According to The Deeds of Suppiluliuma, Zannanza died en route, likely having been murdered. Another Hittite cuneiform source, The Second Plague Prayer of Mursilis II, confirms the outlines of the affair and states outright that Zannanza was killed by hostile Egyptians, who would have had ample time to organize a conspiracy against the dakhamunzu’s doomed suitor.

Some Egyptologists believe the episode took place after the death of Akhenaten and that the dakhamunzu in question was his widow Nefertiti. Many others think that Tutankhamun’s widow Ankhesenamun is the one who sought the Hittite king’s help. If Ankhesenamun is the king’s wife mentioned in The Deeds of Suppiluliuma, perhaps she was alarmed by events in Thebes, where the general — and eventual pharaoh — Horemheb, who likely already had his eye on the throne, was steadily consolidating power. It’s unknown who was responsible for the death of Zannanza, but many members of the Egyptian nobility, not just Horemheb, would gladly have had the Hittite prince assassinated rather than see a foreigner rule over the land of the Nile.

Ramses, the Hittites and the Battle of Kadesh

The Egyptians and Hittites challenged one another for control of the eastern Mediterranean. The Hittites had iron weapons, the Egyptians didn’t. In 1288 B.C., the fifth year of his reign, Ramses and his young sons mounted chariots and led an army of 20,000 men — a huge number at that time — to Syria for a "superpower showdown" against the Hittite king Muwatallis, whose a force was nearly twice as big as the Egyptian force. ♣

At stake was Kadesh, a fortress town in Syria that guarded the trade routes to the east (the Egyptians, and probably, the Hittites imported silk from China). Seti I, Ramses father, had captured the city, but when he returned to Egypt, the Hittites recaptured it.

Ramses's army was surprised by an ambush from the Hittites outside of Kadesh and the Egyptian army scattered. According to an inscription of dubious merit, Ramses found himself abandoned but nevertheless mounted his chariot and led a charge and Egyptian reinforcements arrived and this time the Hittites were on the run. In reality the Egyptians were routed but neither side was able to gain territory on the other, so Ramses went home and raised a monument to declare his great victory.

Ramses led military campaigns against the Hittites until he was in his 40s. After 15 years of fighting the Egyptians and Hittites signed a peace treaty that proved to be so cordial that the Hittite king Hattusilis III sent his eldest daughter,Maat-Hor-Nefersure to wed Ramses II in 1246 B.C. The marriage almost didn't come off because of a last minute argument between Ramses II and Hattusilis over the dowry.

The marriage between Ramses and Maat-Hor-Nefersure ushered in a long period of peace and prosperity that lasted until Ramses' death. Ramses later married another one of Hattusilis's daughters. The Hitittes may have even sent craftsman to Egypt to make iron shields and weapons for the Egyptians. Iron was introduced by the Hittites in the 13th century but wasn't common until the 6th or 7th century B.C.♣

The Battle of Kadesh marked the beginning of a decline for the Hittites. After the fall of the empire a number of small Hittite states were created. By the 8th century they were absorbed by the Assyrians.

See Separate Article: RAMSES II, THE HITTITES AND THE BATTLE OF KADESH africame.factsanddetails.com

Hyksos

The Hittites and the Hykos were the first people in the Middle East to use chariots. Chariots came before mounted riders. Around 1700 B.C., the Hyksos — a mysterious Semitic tribe from Caucasia in the northeast — invaded Egypt from Canaan and routed the Egyptians. The Hyksos were a chariot people. They and the Hittites were the first people to use chariots in the Middle East, an advancement that gave them an advantage over the people they conquered. The Hyksos introduced the horse and chariot to the Egyptians, who later used them to expand their empire.

Hyksos rule over Egypt was brief. They established themselves for a while in Memphis and exactly how they came to power is not clear. Later they established a capital in Avaris, along the Mediterranean in the Nile Delta. During the Second Intermediate Period they ruled northern Egypt while Thebes-based Egyptians ruled southern Egypt. In the 2nd Intermediate Period, the four rulers during 15 and 16 dynasties were Hyksos.

The Hyksos were thrown out of Egypt in 1567 B.C. Chronicles that portray Hyksos rule as cruel and repressive were probably Egyptian propaganda. More likely they came to power within the existing system rather than conquering it and ruled by respecting the local culture and keeping political and administrative systems intact.

3,300-Year-Old Hittite Tablet Describes Civil War and Invasion of Four Cities

A 3,300-year-old, palm-size clay tablet from in May 2023 by Kimiyoshi Matsumura, an archaeologist at the Japanese Institute of Anatolian Archaeology, in Büklükale, a Hittite site about 60 kilometers (37 miles) southeast of Ankara, describes a catastrophic foreign invasion of the Hittite Empire. The invasion took place during a Hittite civil war, apparently in an effort to aid one of the warring factions, according to a translation of the tablet's cuneiform text. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, March 12, 2024]

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Archaeologists think Büklükale was a major Hittite city. The new discovery suggests it was also a royal residence, perhaps on a par with the royal residence in the Hittite capital Hattuša (also spelled Hattusha), about 70 miles (112 kilometers) to the northeast.According to a translation by Mark Weeden, an associate professor of ancient Middle Eastern languages at University College London, the first six lines of cuneiform text on the tablet say, in the Hittite language, that "four cities, including the capital, Hattusa, are in disaster," while the remaining 64 lines are a prayer in the Hurrian language asking for victory. The Hittites used the Hurrian language for religious ceremonies, Matsumura told Live Science, and it appears that the tablet is a record of a sacred ritual performed by the Hittite king. "The find of the Hurrian tablet means that the religious ritual at Büklükale was performed by the Hittite king," he said in an email. "It indicates that, at the least, the Hittite king came to Büklükale … and performed the ritual."

Matsumura and his colleagues have been excavating the ruins at Büklükale for about 15 years. They'd found only broken clay tablets before, but this one is in near-perfect condition.Hurrian was originally the language of the region's Mitanni kingdom, which eventually became a Hittite vassal state. The language is still poorly understood, and experts have spent several months trying to learn the inscription's meaning, Matsumura said.It turns out, the Hurrian writing is a prayer addressed to Teššob (also spelled Teshub), the Hurrian name of the storm god who was the head of both the Hittite and Hurrian pantheons. It praises the god and his divine ancestors, and it repeatedly mentions communication problems between the gods and humans, he said. The prayer then lists several individuals who seem to have been enemy kings and concludes with a plea for divine advice, Matsumura said.

The invasion referenced by the newfound tablet doesn't seem to be related to the Bronze Age collapse. Matsumura said the tablet dates to the reign of the Hittite king Tudhaliya II, between about 1380 to 1370 B.C. — roughly 200 years before the Late Bronze Age collapse. The tablet "seems to come from a period of civil war which we know about from other [Hittite] texts," he said. "During this time, the Hittite heartland was invaded from many different directions at once … and many cities were temporarily destroyed."

Fall of the Hittite Kingdom

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “ Under Tudhaliya IV (r. 1245–1215 B.C.), Hattusha was further strengthened and the king completed the construction of a nearby religious sanctuary. However, during his reign, the empire began to suffer setbacks. The Assyrians launched attacks against the eastern borders of the empire as well as in Syria, reducing Hittite territory in these regions. At the same time, Hittite dependencies in the west were being lost.

Sometime around 1200 B.C., Hattusha was violently destroyed and never recovered. Who destroyed the capital is unknown but it was apparently part of the wider collapse of Hittite power. The reasons for the rapid disappearance of the Hittites, who had dominated Anatolia for centuries, remain unexplained. However, Hittite traditions were maintained in northern Syria by a number of dynasties established under the empire, such as at Carchemish, which continued to flourish through the early centuries of the first millennium B.C. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "The Hittites", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, metmuseum.org \^/]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, Anatolian Civilizations Museum in Ankara

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024