Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

BATTLE OF KADESH

Some regard the Battle of Kadesh as the first true battle. The Egyptians and Hittites challenged one another for control of the eastern Mediterranean. The Hittites had iron weapons, the Egyptians didn’t. In 1288 B.C., the fifth year of his reign, Ramses and his young sons mounted chariots and led an army of 20,000 men — a huge number at that time — to Syria for a "superpower showdown" against the Hittite king Muwatallis, whose a force was nearly twice as big as the Egyptian force. [Source: Rick Gore, National Geographic, April 1991]

At stake was Kadesh, a fortress town in Syria that guarded the trade routes to the east (the Egyptians, and probably, the Hittites imported silk from China). Seti I, Ramses father, had captured the city, but when he returned to Egypt, the Hittites recaptured it.

Ramses's army was surprised by an ambush from the Hittites outside of Kadesh and the Egyptian army scattered. According to an inscription of dubious merit, Ramses found himself abandoned but nevertheless mounted his chariot and led a charge and Egyptian reinforcements arrived and this time the Hittites were on the run. In reality the Egyptians were routed but neither side was able to gain territory on the other, so Ramses went home and raised a monument to declare his great victory.

Ramses led military campaigns against the Hittites until he was in his 40s. After 15 years of fighting the Egyptians and Hittites signed a peace treaty that proved to be so cordial that the Hittite king Hattusilis III sent his eldest daughter,Maat-Hor-Nefersure to wed Ramses II in 1246 B.C. The marriage almost didn't come off because of a last minute argument between Ramses II and Hattusilis over the dowry.

The marriage between Ramses and Maat-Hor-Nefersure ushered in a long period of peace and prosperity that lasted until Ramses' death. Ramses later married another one of Hattusilis's daughters. The Hitittes may have even sent craftsman to Egypt to make iron shields and weapons for the Egyptians.♣

See Separate Article: RIVAL KINGDOMS OF THE HITTITE EMPIRE africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Ancient Egypt Magazine ancientegyptmagazine.co.uk; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Egyptian Study Society, Denver egyptianstudysociety.com; The Ancient Egypt Site ancient-egypt.org; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Eastern Mediterranean in the Age of Ramesses II” by Marc Van De Mieroop Amazon.com;

“When Egypt Ruled the East” by George Steindorff and Keith C. Seele (1963) Amazon.com;

“Qadesh 1300 BC: Clash of the Warrior Kings” (1993) by Mark Healy Amazon.com;

“Battles of the Ancient World 1285 BC - AD 451: From Kadesh to Catalaunian Field”

by Kelly Devries (2011) Amazon.com;

“Warfare in New Kingdom Egypt” by Paul Elliott (2017) Amazon.com;

“War in Ancient Egypt: The New Kingdom” by Anthony J. Spalinger (2008) Amazon.com;

"Ramesses II, Egypt's Ultimate Pharaoh" by Peter Brand Amazon.com;

“Pharaoh Triumphant. The Life and Times of Ramesses II” by Kenneth Kitchen (1990) Amazon.com;

”Pharaoh Seti I: Father of Egyptian Greatness” by Nicky Nielsen (2020) Amazon.com;

“Ramesses: Egypt's Greatest Pharaoh” by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ramesses the Great: Egypt's King of Kings” by Toby Wilkinson Amazon.com;

“The Kingdom of the Hittites” by Trevor R. Bryce (Oxford University Press, 1998) Amazon.com;

“The Hittites and Their World” by Billie Jean Collins (2007) Amazon.com;

“Hattusili, the Hittite Prince Who Stole an Empire: Partner and Rival of Ramesses the Great” by Trevor R. Bryce (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Hittites and Their Contemporaries in Asia Minor” by James G. Macqueen (1975) Amazon.com;

“The Temple of Ramesses II in Abydos: Volume 1, Wall Scenes - Part 1, Exterior Walls and Courts & Part 2, Chapels and First Pylon (2 volumes)” by Sameh Iskander and Ogden Goelet (2015) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“I, the Sun” Novel by Janet Morris (1983) Amazon.com;

"The New Kingdom" by Wilbur Smith, Novel (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Late New Kingdom in Egypt (c. 1300–664 BC) A Genealogical and Chronological Investigation (Oxbow Classics in Egyptology) by M. L. Bierbrier (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz (1978, 2009) Amazon.com;

Background Behind the Battle of Kadesh

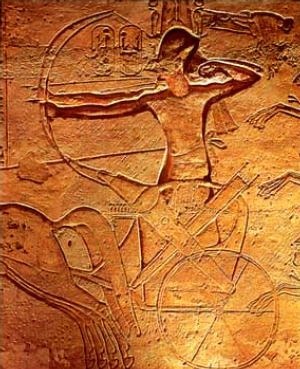

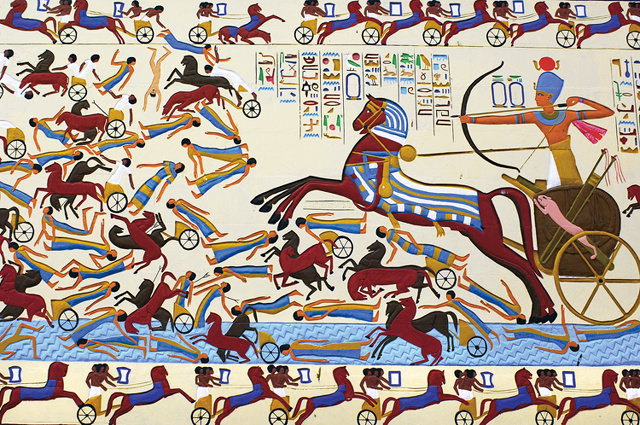

Ramesses II on chariot Ramses II desired northern Syria because of vital routes linking the Caucasus and Anatolia with Mesopotamia. The region was controlled by the Hittites, whose power and prosperity was mostly dependent on control of these routes and metal sources. Although Ramses II inscriptions proclaim victory at the key battle of Kadesh (Qadesh), it seems more likely that Ramses was turned back by the Hittite king Muwatalli. Many historians view the battle at Kadesh as a disaster for the Egyptians — a near defeat caused poor military intelligence on the part of the Egyptians and salvaged only with the help of last-minute arrival of reinforcements from the Lebanese coast. In Ramses II' accounts of the event, which, cover entire walls of some of his monuments, the battle was a dramatic and glorious Egyptian victory achieved single-handedly by Ramses himself. This battle took place in the 5th year of Ramses (c 1275 B.C. by the most commonly used chronology).” [Source: Crystal Links]

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “As was usual in those days, the threat of foreign aggression against Egypt was always at its greatest on the ascension of a new Pharaoh. Subject kings no doubt saw it as their duty to test the resolve of a new king in Egypt. Likewise, it was incumbent on the new Pharaoh it make a display of force if he was to keep the peace during his reign.” [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

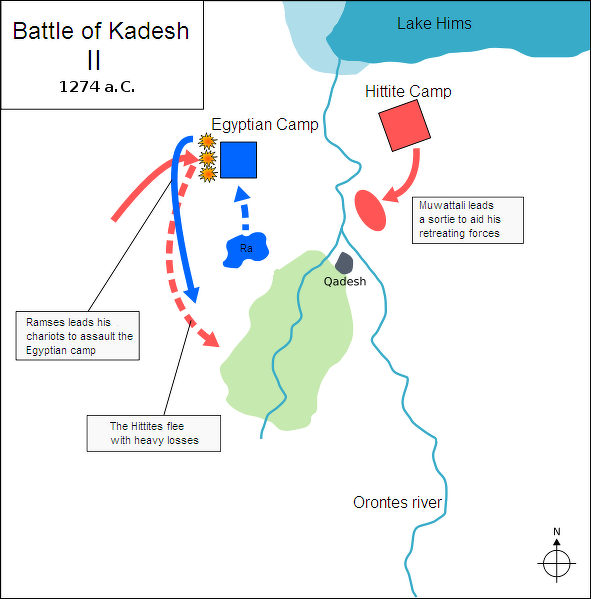

“On his second campaign against the Hittites, Ramses found got himself in trouble attacking “the deceitful city of Kadesh”. “He had divided his army into four sections: the Amun, Ra, Ptah and Setekh divisions. Ramses himself was in the vanguard, leading the Amon division with the Ra division about a mile and a half behind. He had decided to camp outside the city – but unknown to him, the Hittite army was hidden and waiting. They attacked and routed the Ra division as it was crossing a ford. With the chariots of the Hittites in pursuit, Ra fled in disorder – spreading panic as they went. They ran straight into the unsuspecting Amun division. With half his army in flight, Ramses found himself alone. With only his bodyguard to assist him, he was surrounded by two thousand five hundred Hittite chariots. ^^^

“The king, realising his desperate position, charged the enemy with his small band of men. He cut his way through, slaying large numbers as he escaped. “I was,” said Ramses, “by myself, for my soldiers and my horsemen had forsaken me, and not one of them was bold enough to come to my aid.” At this point, the Hittites stopped to plunder the Egyptian camp – giving the Egyptians time to regroup with their other two divisions. They then fought for four hours, at the end of which time both sides were exhausted and Ramses was able to withdraw his troops.” ^^^

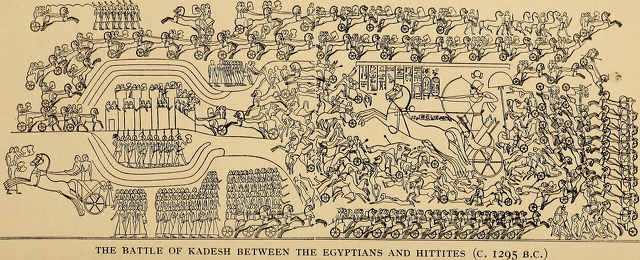

Largest Chariot Battle Ever — at Kadesh

The Hittites and Egyptians fought in the biggest chariot battle ever. Luis Alberto Ruiz wrote in National Geographic: The site of the city of Kadesh lies near Homs in western Syria. In 1275 B.C. it was held by the Hittites. By taking it, Ramses would neutralize the Hittite threat to his northern sphere of interest, and claim the territories once captured by Thutmose III, and since lost. The Egyptian sources for the battle recount how Ramses’ army had been misled into believing the Hittites were far away. On approaching the city, the Egyptians were surprised by the enemy who were concealed behind the town. [Source: Luis Alberto Ruiz, National Geographic, May 1, 2020]

Some 3,000 Hittite chariots and 40,000 foot soldiers smashed into the smaller Egyptian force, which was scattered by the charge. The Egyptian record of the battle uses the imagery of massed chariots to highlight Ramses’ heroic solitude at this moment: “There is no one at my side . . . But I find that [the god] Amun’s grace is better far to me than ten thousand chariots.”

Ramses rallied his forces and managed to fight the battle to a respectable draw, later claiming victory. Despite the boastful claims of his Abu Simbel reliefs, the Hittites continued to dominate Syria. In 1258 B.C., in another sign of Hittite regional strength, Ramses concluded a peace treaty with them. In 1245 B.C. he married a Hittite princess. (Their wedding was one of the biggest in Egyptian history.)

Account of the Battle of Kadesh and Other Hittite Campaigns

"The Asiatic Campaigning of Ramses II", a text that describes the Battle of Kadesh found on the wall of several buildings associated with Ramses II, reads: “Now then, his majesty had prepared his infantry, his chariotry, and the Sherden of his majesty's cap-turing, whom he had carried off by the victories of his arm, equipped with all their weapons, to whom the orders of combat had been given. His majesty journeyed northward, his infantry and chariotry with him. He began to march on the good way in the year 5, 2nd month of the third season, day 9, (when) his majesty passed the fortress of Sile. [He] was mighty like Montu when he goes forth, (so that) every foreign country was trembling before him, their chiefs were presenting their tribute, and all the rebels were coming, bowing down through fear of the glory of his majesty. His infantry went on the narrow passes as if on the highways of Egypt. Now after days had passed after this, then his majesty was in Ramses Meri-Amon, the town which is in the Valley of the Cedar. [Source: James B. Pritchard, “Ancient Near Eastern Texts” (ANET), Princeton, 1969, pp.255-256 web.archive.org]

Hittites with swords, maybe made of iron

“His majesty proceeded northward. After his majesty reached the mountain range of Kadesh, then his majesty went forward like his father Montu, Lord of Thebes, and he crossed the ford of the Orontes, with the first division of Amon (named) "He Gives Victory to User-maat-Re Setep-en-Re.'' His majesty reached the town of Kadesh ....Now the wretched foe belonging to Hatti, with the numerous foreign countries which were with him, was waiting hidden and ready on the northeast of the town of Kadesh, while his majesty was alone by himself with his retinue. The division of Amon was on the march behind him; the division of Re was crossing the ford in a district south of the town of Shabtuna, at the dis-stance of one iter from the place where his majesty was ; the division of Ptah was on the south of the town of Arnaim; and the division of Seth was marching on the road. His majesty had formed the first ranks of battle of all the leaders of his army, while they were (still) on the shore in the land of Amurru ....

Year 5, 3rd month of the third season, day 9, under the majesty of (Ramses II). When his majesty was in Djahi on his second victorious campaign, the goodly awakening in life, prosperity, and health was at the tent of his majesty on the mountain range south of Kadesh. After this, at the time of dawn, his majesty appeared like the rising of Re, and he took the adornments of his father Montu. The lord proceeded northward, and his majesty arrived at a vicinity south of the town of Shabtuna.... [add full text of battle here]

Another text related to later campaigning by Ramses II against the Hittites reads: “ The town which his majesty desolated in the year 8, Merom. The town which his majesty desolated in the year 8, Salem. The town which his majesty desolated on the mountain of Beth-Anath, Kerep (Palestine ?). The town which his majesty desolated in the land of Amurru, Deper (region of Tunip in Syria?). The town which his majesty desolated, Acre. The wretched town which his majesty took when it was wicked, Ashkelon. It says: "Happy is he who acts in fidelity to thee, (but) woe (to) him who transgresses. thy frontier! Leave over a heritage, so that we may relate thy strength to every ignorant foreign country!”

The Beth-Shan Stelae of Ramses reads: “Year 9, 4th month of the second season, day 1 ... When day had broken, he made to retreat the Asiatics .... They all come bowing down to him, to his palace of life and satisfaction, Per-Ramses-Meri-Amon-the-Great of Victories (the capital in Delta). [Source: II ANET., p.254. BASOR (1952): 24-32]

Images of the Battle of Kadesh at Ramesseum

The account that the inscriptions give us of this battle is confirmed by the great series of pictures on the pylons of the Ramesseum (the funerary temple of Ramses II) we see there how the two captured spies of the prince of the Hittites are induced by a merciless torture to betray their secret, and how the king, seated on “his golden throne," after hearing the fatal news, wastes his time by demonstrating to his princes the uselessness of his own officers. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Next we see how the soldiers of the “first army of Amun “pitch their camp; the shields are placed side by side so as to construct a great four-cornered enclosure. One entrance only is left, and this is fortified with barricades and is defended by four divisions of infantry. In the middle of the camp a large square space indicates the position of the royal tent; the smaller tents of the officers surround it. The wide space between these tents and the outer enclosure serves as a camping-ground for the common soldiers and for the cattle, and here we see a series of life-like scenes, in the representation of which the Egyptian artist has evidently taken great delight. In one corner stand the rows of war-chariots; the horses are unharnessed and paw the ground contentedly, while they receive their food.

Close by are posted the two-wheeled baggage cars; the oxen are looking round at the food, and do not appear to trouble themselves about the king's big tame lion, which has lain down near them wearied out. The most characteristic animal in the camp, however, is the donkey with his double panniers, in which he has to carry the heavy sacks and jars of provisions. We meet with him here, there, and everywhere, in all manner of positions; for instance, he drops on his knee indignantly, as if he could carry his panniers no longer; he prances about when the soldiers want to lade him with the sacks; he lies down and brays, or he takes his ease rolling in the dust near his load. The boys also, whose business it is to fasten up the donkeys to pegs, contribute to the general liveliness of the camp; in more than one place they have begun to quarrel about their work, and in their anger they beat each other with the pegs. Other boys belonging to the camp have to hang the baggage on posts, or to bring food for the soldiers, or to fetch the skins of water. These boys insist upon quarrelling too; the skins are thrown down, and they use their fists freely.

In contrast to these scenes of daily life in the camp, we have on the other hand a representation of the wild confusion of battle. " Close to the bank of the Orontes is the royal chariot, in which the king stands drawn up to his full height; behind and on each side the chariots of the Hittites surround him, while many more are crossing the stream. The Egyptian chariots are indeed in the rear of the king, but in order to come to his help they would have first to force a way through the chariots of the Hittite. In the meantime, the Pharaoh fights by himself, and pours down such a frightful rain of arrows on the enemy that they fly in wild confusion. Hit by the arrows, their horses take fright, dash the chariots to pieces, and throw out the warriors, or they get loose and breaking through their own ranks, spread confusion everywhere. The dead and the wounded Hittites fall one upon another; those who escape the arrows of the king throw themselves into the Orontes and try to swim across to Kadesh, which is seen on the opposite bank surrounded by walls and trenches. All do not succeed in making their way through this confusion of horses and men, and in swimming the stream; thus we see the soldiers pulling out the body of the prince of Charbu from the water. Cherpaser, the “scribe of letters “of the prince of the Hittites, was also drowned; T'ergannasa and Pays his chariot drivers were shot, as were also T'e'edura, the chief of his bodyguard, Kamayta the commander of the corps of elite, 'Aagem, a chief of the mercenaries, and several other men of rank; Met'arema, the brother of the prince of the Hittites, fell before he could reach the stream to save himself.

Whilst the Pharaoh thus slays the Hittites, the prince of the latter people stands watching the battle from the corner between Kadesh and the Orontes in the midst of a mighty square of 8000 foot soldiers of the elite of his troops; “he does not come out to fight, because he is afraid before his Majesty, since he has seen his Majesty. " When he sees that the battle is lost, he says in admiration: “He is as Seth the glorious, Ba'al lives in his body. "

Poem on the Battle of Kadesh

The Battle of Kadesh has been detailed in the poem of Pentaur, the son of Ramses III. In the poem, Ramses II is exalted as a great warrior and leader. The poem was inscribed upon the walls of five temples, one of which was at Karnak, on orders of Ramses II. Accompanying poem on these walls were enormous engraved illustrations of the scenes of the poem. Many commemorate the exploits of Ramses II in his battle with the Hittites. In the poem the Khita is the Egyptian name foe the Hittites.

Pen-ta-ur’s Victory of Ramses II Over the Khita: (1326 B.C.) reads

“THEN the king of Khita-land,

With his warriors made a stand,

But he durst not risk his hand

In battle with our Pharaoh;

So his chariots drew away,

Unnumbered as the sand,

And they stood, three men of war

On each car;

And gathered all in force

Was the flower of his army,

for the fight in full array,

But advance, he did not dare,

Foot or horse.

[Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. III: Egypt, Africa, and Arabia, trans. W. K. Flinders Petrie, pp. 154-162]

“So in ambush there they lay,

Northwest of Kadesh town;

And while these were in their lair,

Others went forth south of Kadesh,

on our midst, their charge was thrown

With such weight, our men went down,

For they took us unaware,

And the legion of Pra-Hormakhu gave way.

“But at the western side

Of Arunatha's tide,

Near the city's northern wall,

our Pharaoh had his place.

And they came unto the king,

And they told him our disgrace;

Then Ramses uprose,

like his father, Montu in might,

All his weapons took in hand,

And his armor did he don,

Just like Baal, fit for fight;

And the noble pair of horses that carried Pharaoh on,

Lo! "Victory of Thebes" was their name,

And from out the royal stables of great Miamun they came.

Hittites Attack Ramses II in the Poem

“Then the king he lashed each horse,

And they quickened up their course,

And he dashed into the middle of the hostile, Hittite host,

All alone, none other with him, for he counted not the cost.

Then he looked behind, and found

That the foe were all around,

Two thousand and five hundred of their chariots of war;

And the flower of the Hittites, and their helpers, in a ring —

Men of Masu, Keshkesh, Pidasa, Malunna, Arathu,

Qazauadana, Kadesh, Akerith, Leka and Khilibu —

Cut off the way behind,

[Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. III: Egypt, Africa, and Arabia, trans. W. K. Flinders Petrie, pp. 154-162]

Retreat he could not find;

There were three men on each car,

And they gathered all together, and closed upon the king.

"Yea, and not one of my princes, of my chief men and my great,

Was with me, not a captain, not a knight;

For my warriors and chariots had left me to my fate,

Not one was there to take his part in fight."

“Then spake Pharaoh, and he cried:

"Father Ammon, where are you?

Shall a sire forget his son?

Is there anything without your knowledge I have done?

From the judgments of your mouth when have I gone?

Have I e'er transgressed your word?

Disobeyed, or broke a vow?

Is it right, who rules in Egypt, Egypt's lord,

Should e'er before the foreign peoples bow,

Or own their rod?

Whate'er may be the mind of this Hittite herdsman horde,

Ramses II Pleas for Help from the Gods

Sure Ammon at should stand higher

than the wretch who knows no God?

Father Ammon, is it nought

That to you I dedicated noble monuments, and filled

Your temples with the prisoners of war?

That for you a thousand years shall stand the shrines

I dared to build?

The king, probably, is here identifying himself with Ammon.

That to you my palace-substance I have brought,

That tribute unto you from afar

A whole land comes to pay,

That to you ten thousand oxen for sacrifice I fell,

And burn upon your altars the sweetest woods that smell;

That all your heart required, my hand did ne'er gainsay?

I have built for you tall gates and wondrous works beside the Nile,

I have raised you mast on mast,

For eternity to last,

[Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. III: Egypt, Africa, and Arabia, trans. W. K. Flinders Petrie, pp. 154-162]

From Elephantin's isle

The obelisks for you I have conveyed,

It is I who brought alone

The everlasting stone,

It is I who sent for you,

The ships upon the sea,

To pour into your coffers the wealth of foreign trade;

Is it told that such a thing

By any other king,

At any other time, was done at all?

Let the wretch be put to shame

Who refuses your commands,

But honor to his name

Who to Ammon lifts his hands.

To the full of my endeavor,

With a willing heart forever,

I have acted unto you,

And to you, great God, I call;

For behold! now, Ammon, I,

In the midst of many peoples, all unknown,

Unnumbered as the sand,

Here I stand,

All alone;

There is no one at my side,

My warriors and chariots afeared,

Have deserted me, none heard

My voice, when to the cravens I, their king, for succor, cried.

But I find that Ammon's grace

Is better far to me

Than a million fighting men and ten thousand chariots be.

Yea, better than ten thousand, be they brother, be they son,

When with hearts that beat like one,

Together for to help me they are gathered in one place.

The might of men is nothing, it is Ammon who is lord,

What has happened here to me is according to your word,

And I will not now trangress your command;

But alone, as here I stand,

To you my cry I send,

Unto earth's extremest end,

Saying, 'Help me, father Ammon, against the Hittite horde."'

“Then my voice it found an echo in Hermonthis' temple-hall,

Ammon heard it, and he came unto my call;

And for joy I gave a shout,

From behind, his voice cried out,

"I have hastened to you, Ramses Miamun,

Behold! I stand with you,

Behold! 'tis I am he,

Own father thine, the great god Ra, the sun.

Lo! mine hand with thine shall fight,

And mine arm is strong above

The hundreds of ten thousands, who against you do unite,

Of victory am I lord, and the brave heart do I love,

I have found in you a spirit that is right,

And my soul it does rejoice in your valor and your might."

Ramses II’s Escape from the Hittites

“Then all this came to pass, I was changed in my heart

Like Monthu, god of war, was I made,

With my left hand hurled the dart,

With my right I swung the blade,

Fierce as Baal in his time, before their sight.

Two thousand and five hundred pairs of horses were around,

And I flew into the middle of their ring,

By my horse-hoofs they were dashed all in pieces to the ground,

None raised his hand in fight,

For the courage in their breasts had sunken quite;

And their limbs were loosed for fear,

And they could not hurl the dart,

And they had not any heart

To use the spear;

And I cast them to the water,

Just as crocodiles fall in from the bank,

So they sank.

And they tumbled on their faces, one by one.

At my pleasure I made slaughter,

So that none

E'er had time to look behind, or backward fled;

Where he fell, did each one lay

On that day,

From the dust none ever lifted up his head.

“Then the wretched king of Khita, he stood still,

With his warriors and his chariots all about him in a ring,

Just to gaze upon the valor of our king

In the fray.

And the king was all alone,

Of his men and chariots none

To help him; but the Hittite of his gazing soon had fill,

For he turned his face in flight, and sped away.

Then his princes forth he sent,

To battle with our lord,

Well equipped with bow and sword

And all goodly armament,

Chiefs of Leka, Masa, Kings of Malunna, Arathu,

Qar-qa-mash, of the Dardani, of Keshkesh, Khilibu.

And the brothers of the king were all gathered in on place,

Two thousand and five hundred pairs of horse —

And they came right on in force,

The fury of their faces to the flaming of my face.

[Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. III: Egypt, Africa, and Arabia, trans. W. K. Flinders Petrie, pp. 154-162]

“Then, like Monthu in his might,

I rushed on them apace,

And I let them taste my hand

In a twinkling moment's space.

Then cried one unto his mate,

"This is no man, this is he,

This is Sutek, god of hate,

With Baal in his blood;

Let us hasten, let us flee,

Let us save our souls from death,

Let us take to heel and try our lungs and breath."

And before the king's attack,

Lands fell, and limbs were slack,

They could neither aim the bow, nor thrust the spear,

But just looked at him who came

Charging on them, like a flame,

And the King was as a griffin in the rear.

Behold thus speaks the Pharaoh, let all know,

I struck them down, and there escaped me none

Then I lifted up my voice, and I spake,

Ho! my warriors, charioteers,

Away with craven fears,

Halt, stand, and courage take,

Behold I am alone,

Yet Ammon is my helper, and his hand is with me now."

“When my Menna, charioteer, beheld in his dismay,

How the horses swarmed around us, lo! his courage fled away,

And terror and affright

Took possession of him quite;

And straightway he cried out to me, and said,

“"Gracious lord and bravest king, savior-guard

Of Egypt in the battle, be our ward;

Behold we stand alone, in the hostile Hittite ring,

Save for us the breath of life,

Give deliverance from the strife,

Oh! protect us, Ramses Miamun!

Oh! save us, mighty King!"

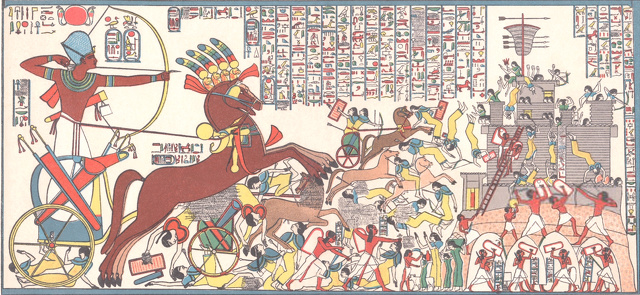

Modern interpretation of a Battle of Kadesh scene from the Ramesseum at the Pharaonic Village in Cairo

“Then the King spake to his squire,

"Halt! take courage, charioteer,

As a sparrow-hawk swoops down upon his prey,

So I swoop upon the foe, and I will slay,

I will hew them into pieces, I will dash them into dust;

Have no fear,

Cast such evil thought away,

These godless men are wretches that in Ammon put no trust."

Then the king, he hurried forward, on the Hittite host he flew,

"For the sixth time that I charged them," says the king — and listen well,

"Like Baal in his strength, on their rearward, lo! I fell,

And I killed them, none escaped me, and I slew, and slew, and slew."

Storming of Fortresses in Syria and Palestine

The Battle of Kadesh was not really a decisive victory. The war carried on afterwards for many years, and indeed with varying success, for we find the Pharaoh fighting, sometimes in the country of the Hittites, and sometimes close to his own frontier. The Hittites built fortresses in towns in Syria and Palestine. These fortresses have always essentially the same form; through the strong gates entrance is obtained to the broad lower story, which is crowned with battlements above, and provided on each side with four widely-projecting balconies; abo\e this story is a second narrower one with similar balconies, and barred windows. Several pictures represent the storming of these fortresses.

For example, near Ashkelon, a citadel was built on a hill. Its strong position however does not save it; the Egyptian soldiery force their way through the enemy to the walls, they burst open the gates with axes, they plant mighty scaling-ladders against the walls, and ascend, with their shields on their backs and their daggers drawn, to the first story. The inhabitants, who with their wives and children have taken refuge in the upper floor, seeing their destruction approach, are in despair; some try to let down the women and children over the wall, others crave the king's mercy, raising their hands in supplication.

The storming by Ramses II at Dapur which is represented in our illustration, was on a larger scale, and a more difficult affair. This fortress, as we see, deviates somewhat from the ordinary style of building. Below, a battlcmented wall surrounds an immense lower building, which supports four towers, the largest of which has windows and balconies. Above the towers is seen the standard of the town, a great shield pierced through with arrows. Outside, on the field of battle, the king fights the Hittites, who have hastened to the relief of the fortress; while under the conduct of his sons a systematic attack is made on the town.

In order to protect themselves from the shower of stones and arrows that the besieged pour down from above, the Egyptian soldiers advance under cover of pent-houses, which are pushed forward with poles. Then ensues the actual storming of the fortress by means of scaling-ladders, and again we find that it is two of the princes who, with almost incredible boldness, are climbing up the rungs of the scaling-ladders. Then we see the course of events round the fortress: some of the besieged let themselves down over the wall, more than one being killed in this attempt to escape; others bring tribute to the victors, and “say, whilst they adore the good god, ' Give us the breath of life, thou good ruler; we lie under the soles of thy feet. ' "

Booty, Celebrations and Stalemate in the War with the Hittites

“I have defied all nations," Ramses II boasted, “when I was alone, and my infantry and my chariot force had forsaken me; not one of them stood still or returned! I swear however that as truly as Ra loves me, and as truly as Atum rewards me, I myself truly did all that I have said, in the sight of my infantry and of my chariot force. " [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

After this success the good god returns home from the campaign, with “very great booty, the like of which had never been seen before," ' and the "living captives, which his hand had spared";" at the frontier canal, at the fortress T'aru, the great prophets and the princes of the south and of the north await him with their greeting. The priests have placed themselves on the right, and present to him, as if they were presenting an offering, large bouquets of flowers; on the left, their hands raised in supplication, stand the high officials, with the bald-headed governor at their head. “Welcome," they say, “from the countries that thou hast subdued; thy cause has conquered, and thine enemies are subject to thee. Thou shalt be king as long as Ra rules in heaven, and shalt renew thy courage. Thou lord of the people of the nine bows! Ra makes fast thy frontiers, and spreads out his arms as a protection behind thee. Thine axe strikes the heart of all countries, and their princes fall before thy sword. " '

The common people also take part in these rejoicings: “the young people of the triumphal town put on festive garments every day and (pour) pleasant oil on their heads, on their new coiffures; they stand at their doors, bouquets in their hands, Uad'et flowers from the temple of Hathor, and Mchet flowers from the tank; on the day when Ramses II makes his entry, the god of war of the two countries, on the morning of the Kaherka festival. Every one joins with his neighbour and recites his adoration. "

The facts that the actual results of the war were small, and that though Ramses II herewith closed two decades of the campaign, the enemy was yet acknowledged as an equal, seem not to have interfered with this celebration of the victory. We learn that in the 21st year, on the 22nd of Tybi, when the king repaired to the town, the house of Ramses, Tartesebu and Ramses, the Hittites ambassadors, were conducted into his presence, in order to “sue for peace from the Majesty of Ramses, the bull of the princes, who places his boundaries in every country where he will. " As a matter of fact however, they were the bearers of a document, concerning the peace which had already been concluded, a document which in no way reads like an enemy suing for peace.

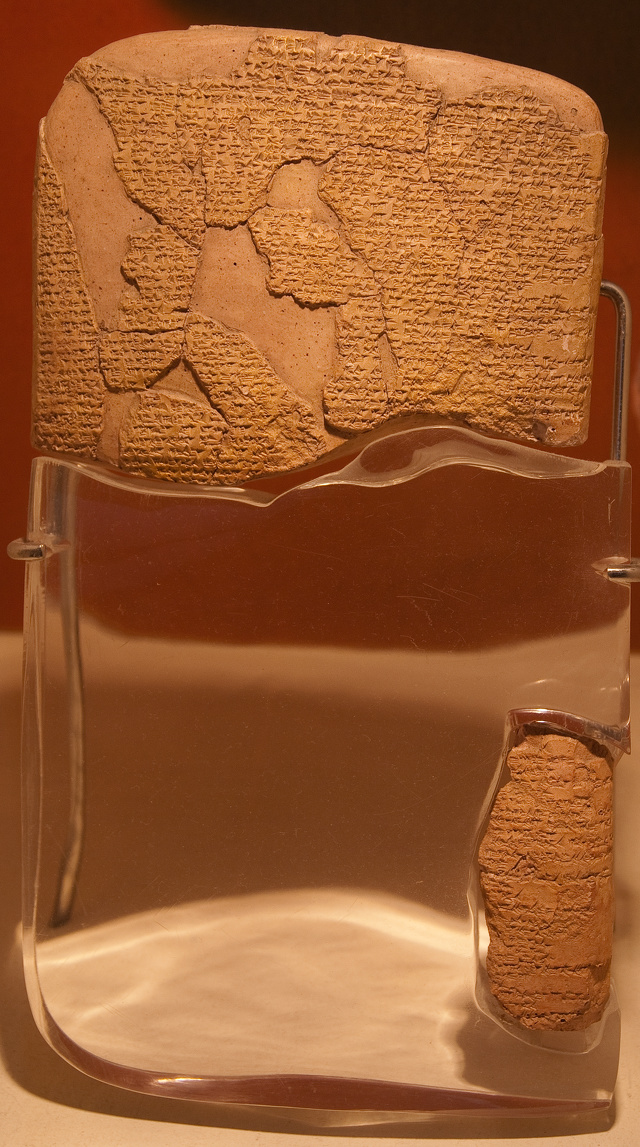

Peace Treaty After the Battle of Kadesh

Neither the Egyptians nor the Hittites were able to get the upper hand, and finally — after 20 years of war — Ramses made a peace treaty with the Hittites. John Ray of Cambridge University wrote: “The empty victory of Kadesh was followed by a greater achievement, an international peace treaty with the Hittites, a copy of which is now on the wall of the General Assembly building of the United Nations. The treaty covers extradition, arbitration of disputes, and mutual economic aid, a clause which was later honoured by the Egyptians when their old enemies were afflicted with food shortage.” [Source: John Ray, Cambridge University, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com:“It was agreed that Egypt was not to invade Hittite territory, and likewise the Hittites were not to invade Egyptian territory. They also agreed on a defence alliance to deter common enemies, mutual help in suppressing rebellions in Syria, and an extradition treaty. Thirteen years after the conclusion of this treaty in the thirty-fourth year of his reign, Ramses married the daughter of the Hittite prince. Her Egyptian name was Ueret-ma-a-neferu-Ra: meaning ” Great One who sees the Beauties of Ra”. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Added as a supplement to the treaty, is a proviso, which, though not of wide-reaching importance, is very characteristic of the relations that had hitherto existed between the two great kingdoms. During the war many of the Hittites had gone over to the Egyptians, and many Egyptians had gone over to the Hittites — for instance, we meet with one of the Hittites named Ramses — these had of course been received with open arms by the enemy. Now after the peace the question arose as to what should be done with these deserters, and how the two powers could disembarrass themselves of them in a fitting manner. The agreement which they came to on the subject runs thus: "If men have fled from the country of Egypt, if it be one man or two men or three men, and have come to the great prince of the Hittites, then shall the great prince of the Hittites take them into custody and cause them to be brought back to Ramses II the great monarch of Egypt. But with regard to him who is brought back to Ramses II the great monarch of Egypt, his crime shall not be brought up against him, neither shall his house nor his wives nor his children be (destroyed), neither shall his mother be slain, and he shall not be (punished) neither in his eyes nor in his mouth nor in his feet; and no crime whatever shall be brought up against him. " The same clause was enacted for the Hittites who had gone over to the Pharaoh.” [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

This remarkable document, which gives us a glimpse behind the scenes, shows us at the same time the true facts hidden beneath the bombastic phrases of the inscriptions, and marks at once a new departure in Egyptian politics — Egypt acknowledging the Hittites as an equal power, with whom she had to share the supremacy in Palestine. This friendly relationship was an enduring one; Ramses II married a daughter of the king of the Hittites, and when on one occasion the latter came to Egypt to visit his son-in-law, the Pharaoh caused him to be represented as a prince by his side in the temple of Abu Simbel. It was indeed an unheard-of thing that a “barbarian prince”, a “miserable chief," according to the customary expression, should be represented on a public monument as the associate of the Pharaoh; this was, as it were, an earnest of the new era that was approaching for Egypt.

The immediate and natural consequence of these years of peace was an increase of intercourse between the two countries; in fact, the friendship of the Pharaoh towards the prince of the Hittites went so far that he even sent to the latter ships of grain, when his country was suffering from a period of great calamity. " In spite of these friendly relations, the northeast frontier of Egypt was still carefully guarded by soldiers, for though Egypt might now be in the peaceful possession of the south of Palestine, yet the latter contained so many nomadic elements, that, even under the strictest rule, the tribes could not entirely be restrained from their predatory habits.

Ramses II’s Spin on the Battle of Kadesh

A relief from Abu Simbel tells the story of the Battle of Kadesh. Pharoah Ramses II can be seen firing arrows from his chariot surrounded by swarms of smaller attacking Hittite charioteers. Luis Alberto Ruiz wrote in National Geographic: For an Egyptian noble, living in or just after the time of Ramses II, the truth must have seemed clear and simple: In a heroic push to regain their former imperial lands in Syria, their great pharaoh had waged war against the Hittites at the Battle of Kadesh in 1275 B.C., where he had won a resounding victory.

Ramses was as much a master of public relations as he was of war, and historians now know that the Battle of Kadesh was not a definitive victory over the Hittites. It was almost certainly a draw. As masters of an empire that stretched through much of modern Turkey to parts of Syria, the Hittites were a worthy, formidable opponent. Based in their fortified capital of Hattusa (about 130 miles east of Ankara, Turkey, today), they rose to regional dominance in part because of their mastery of the chariot. Facing ranks of thousands of their chariots at Kadesh was certainly something for Ramses the Great to boast about. [Source: Luis Alberto Ruiz, National Geographic, May 1, 2020]

The official Egyptian record of the “victory,” the Poem of Pentaur, was inscribed on Ramses’ temples, including Abu Simbel in southern Egypt. The poem recounts how the Hittite king Muwatallis II “had sent men and horses, multitudinous as the sands … The charioteers of His Majesty [Ramses] were discomfited before them, but His Majesty stood firm.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024