Home | Category: Babylonians and Their Contemporaries / Neo-Babylonians / Deities

MARDUK

The main Babylonian god was Marduk while the main Assyrian god was Ashur. Ultimately simply called Bel, or Lord, Marduk was the chief god of the city of Babylon and the national god of Babylonia. Originally he seems to have been a god of thunderstorms. A poem, known as Enuma elish, dating from the reign of Nebuchadrezzar I (1124-03 B.C.), describes Marduk as being so powerful and all-encompassing that he has 50 names, each one a deity or of a divine attribute. He became "lord of the gods of heaven and earth" after conquering the monster of primeval chaos, Tiamat. All nature, including man, was created by him. The destiny of kingdoms and individuals was in his hands. [Source: Kenneth Sublett, piney.com]

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Statues of gods featured prominently throughout the ancient world, but many of those that are best known from literary evidence have never been found. These include a wooden statue of the Babylonian god Marduk that was covered in gold and silver and housed in Babylon’s main temple. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine November/December 2023]

See Separate Article ISHTAR (INANNA) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RELATED ARTICLES:

MESOPOTAMIAN DEITIES: EVOLUTION, MEANING, IMAGES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MESOPOTAMIAN DEMONS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

IMPORTANT MESOPOTAMIAN DEITIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BABYLONIAN DEITIES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary” by Jeremy Black (1992) Amazon.com;

“Sumerian Gods and Their Representations” by Irving L. Finkel, Markham J. Geller (1997) Amazon.com;

“Anunnaki Gods: The Sumerian Religion” by Joshua Free Amazon.com;

“A Handbook of Gods and Goddesses of the Ancient Near East: Three Thousand Deities of Anatolia, Syria, Israel, Sumer, Babylonia, Assyria, and Elam” by Douglas R. Frayne , Johanna H. Stuckey, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer” by Diane Wolkstein (1983) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography” by Wayne Horowitz (2011) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion” by Thorkild Jacobsen (1976) Amazon.com;

“A Handbook of Ancient Religions” by John R. Hinnells (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture” by Francesca Rochberg Amazon.com

Marduk and Other Gods

Morris Jastrow said: “Anu, Enlil, Ea, presiding over the universe, are supreme over all the lower gods and spirits combined as Annunaki and Igigi, but they entrust the practical direction of the universe to Marduk, the god of Babylon. He is the first-born of Ea, and to him as the worthiest and fittest for the task, Anu and Enlil voluntarily commit universal rule. This recognition of Marduk by the three deities, who represent the three divisions of the universe—heaven, earth, and all waters,—marks the profound religious change that was brought about through the advance of Marduk to a commanding position among the gods. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“From being a personification of the sun with its cult localised in the city of Babylon, over whose destinies he presides, he comes to be recognised as leader and director of the great Triad. Corresponding, therefore, to the political predominance attained by the city of Babylon as the capital of the united empire, and as a direct consequence thereof, the patron of the political centre becomes the head of the pantheon to whom gods and mankind alike pay homage. The new order must not, however, be regarded as a break with the past, for Marduk is pictured as assuming the headship of the pantheon by the grace of the gods, as the legitimate heir of Anu, Enlil, and Ea.

Marduk from Elam

“There are also ascribed to him the attributes and powers of all the other great gods, of Ninib, Shamash, and Nergal, the three chief solar deities, of Sin the moon-god, of Ea and Nebo, the chief water deities, of Adad, the storm-god, and especially of the ancient Enlil of Nippur. He becomes like Enlil “the lord of the lands,” and is known pre-eminently as the bel or “lord.” Addressed in terms which emphatically convey the impression that he is the one and only god, whatever tendencies toward a true monotheism are developed in the Euphrates Valley, all cluster about him.

Marduk“ is so constantly termed the “son of Ea” that there can be no doubt of his having originated in the region of the Persian Gulf at the head of which lay Eridu, the seat of the worship of Ea. Ea and Marduk thus bear the same relation to each other as do Enlil and Ninib on the one hand, and Anu and Enlil on the other. Of the character of Ea there is fortunately no doubt. He is the god of the waters, and the position of Eridu, at (or near) the point where the Euphrates and Tigris empty into the Persian Gulf, suggests that he is more particularly the guardian spirit of these two streams.

“Pictured as half-man, half-fish, he is the skar Apsi, “King of the Watery Deep.” The “Deep,” however, is not the salt ocean but the sweet waters flowing under the earth, which feed the streams, and through streams and canals irrigate the fields. This Apsu was personified, and presented a contrast and opposition to Tiamat, the personification of the salt ocean. The creation myth of Eridu, therefore, pictures a conflict at the beginning of time between Apsu and Tiamat, in which the former, under the direction of Ea, triumphs and holds in check the forces accompanying the monster Tiamat.”

Rise of Marduk — Babylon's God King

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: In the third millennium B.C., Babylon was a small, obscure city. Marduk was a minor deity with equally obscure origins who seems to have been associated with agriculture and canals, and whose symbol was a spade. During this period, Nippur was Mesopotamia’s most sacred city, and its god, Enlil, wielded ultimate divine power. But in the second millennium B.C., especially during the reign of Hammurabi (r. ca. 1792–1750 B.C.), Marduk became an ever more consequential god. As Babylon’s influence grew, he assumed the powers and name of Addu, a storm god who was the patron deity of the city of Halab, modern-day Aleppo. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, March/April 2022]

Toward the end of his reign, Hammurabi defeated the ruler of the city of Eshnunna, which had been allied with the Elamite people who lived in modern-day Iran and posed a constant threat to Babylonia. At the same time, cuneiform texts celebrated Marduk’s victory over Eshnunna’s patron god Tishpak. Marduk then appropriated Tishpak’s chief symbol, the lion-dragon hybrid beast known as mušhuššu, or “furious snake,” with whom he would be associated for the rest of Babylonian history. Depictions of mušhuššu that decorated the city’s famed Ishtar Gate, which was built more than 1,000 years later, still commemorated Marduk’s victory over Tishpak, and Babylon’s over an important ally of Elam.

By the twelfth century B.C., Marduk played a central role in an updated Mesopotamian creation story known as the Enuma Elish, which later cuneiform tablets preserve in many versions. The standard account of this narrative legitimized the god’s position as ruler of the divine pantheon once headed by Enlil and explains how Babylon supplanted Nippur as Mesopotamia’s most important religious center. In the creation myth, Marduk is a young warrior god and the only deity willing to do combat with Tiamat, the goddess of the sea and embodiment of chaos. In return for facing Tiamat, the gods agree to make Marduk king of the gods. Upon killing the goddess, Marduk claims his throne and brings order to the cosmos and creates the world. He makes Babylon the first city and home to his Esagila temple, where Marduk lived in the form of his sacred statue. This version of the Enuma Elish completely ignores Enlil and his sacred city of Nippur, erasing Babylon’s rival from the creation story.

Babylon’s status as Mesoptomia’s chief city waxed and waned, and it was sometimes captured by outside powers, events Marduk’s followers needed to account for. One text known as the Marduk Prophecy recounts how Babylonians sometimes angered the god. Their city was consequently then seized by enemies such as the Hittites from Anatolia and Elamites, each of whom “godnapped” Marduk by capturing his sacred statue and taking it back to their respective capitals. The prophecy refers to these events as the travels of Marduk, as if the god chose to be borne away to foreign lands. Those second millenium B.C. sojourns were brought to an end by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezar I (r. ca. 1125–1104 B.C.), during whose reign the Enuma Elish may have first been written down. The king sacked the Elamite city of Susa, reclaimed Marduk’s statue, and brought it back home to Babylon, once again establishing it as Mesopotamia’s capital of both earthly and cosmic rule.

Marduk Replaces the Sumerian God Enlil as the Main Mesopotamian God

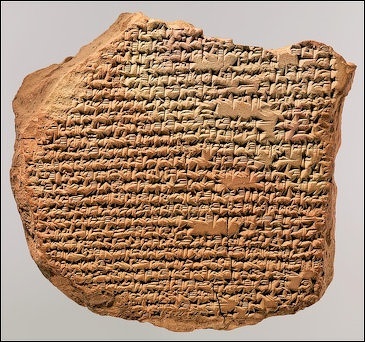

Inscription from Ekur, the temple of Enlil

Morris Jastrow said: “We see the same process repeated, though under somewhat different circumstances, at a subsequent period when, in consequence of the political ascendency of Babylon, Marduk is advanced to the head of the systematised pantheon. The time-honoured nature myth, somewhat modified in form, is transferred to him, but by this time the Ninib cult had receded into the background, and Enlil alone is introduced as transferring his powers and attributes to Marduk. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“Marduk is represented as replacing Enlil, from which one might conclude that, as a further compromise between Enlil and Ninib, the myth was actually told of both, despite the incongruity involved in making a storm-god the conqueror of chaotic confusion. This is not only possible but probable, since, with the expansion of Enlil into a god presiding over vegetation, thus taking on the traits of a sun-god, his original character would naturally be obscured. As he was the head of the pantheon, possessing all the powers attributed to other gods, the tendency would arise to make him the central figure of all myths—the pre-eminent hero and conqueror. At the same time Ninib, as the old-time solar deity of Nippur, also absorbs the duties of other solar gods worshipped in other centres. He is identified with a god Ningirsu, “the lord of Girsu,”—a section of Lagash—who became the chief god of the district controlled by Gudea and his predecessors, of whose solar character there can be no doubt.

“In a certain hymn Ninib, is associated not only with Girsu, which here as elsewhere stands for Lagash and the district of which it was the centre, but also with Kish whose patron deity was known as Zamama. In this same composition he is identified also with Nergal, the solar deity of Uruk, with Lugal-Marada, “King of Marada,” the designation of the solar god localised in Marada, and with the sun-god of Isin. The god Ninib appears to have become in fact a general designation for the sun and the sun-god, though subsequently replaced by Babbar, “the shining one,” the solar deity of Sippar. This title in its Semitic form, Shamash, eventually became the general designation for the “sun” because of the prominence which Sippar, through the close association between Sippar and Babylon, acquired as a centre of the sun cult.

Enuma Elish, The Fifty Names of Marduk

Enuma Elish, The Fifty Names of Marduk, Tablet VIb - VII begins:

<br/>Let us then proclaim his fifty names:..'He whose ways are orious, whose deeds are likewise,

(1) MARDUK, as An, his father,"' called him from his birth;...

Who provides grazing and drinking places, enriches their stalls,

Who with the flood-storm, his weapon, vanquished the detractors,

(And) who the gods, his fathers, rescued from distress.

Truly, the Son of the Sun,"' most radiant of gods is he.

In his brilliant light may they walk forever!

On the people he brought forth, endowed with li[fe]...

The service of the gods he imposed that these may have ease.

Creation, destruction, deliverance, grace-

Shall be by his command."' They shall look up to him! [Source: E. A. Speiser, piney.com]

(2) MARUKKA verily is the god, creator of all,

Who gladdens the heart of the Anunnaki (earth spirits), appeases their [spirits].

(3) MARUTUKKU verily is the refuge of the land, protection of its people].

Unto him shall the' people give praise.

(4) BARASHAKUSHU... stood up and took hold of its... reins;

Wide is his heart, warm his sympathy. [Source: E. A. Speiser]

Hymn to Marduk cuneiform tablet

(5) LUCALDIMMFRANKIA is his name which we

proclaimed in our Assembly.

His commands we have exalted above the gods, his fathers.

Verily, he is lord of all the gods of heaven and earth,

The king at whose discipline the gods above and below are in mourning."

(6) NARI-LUGALDIMMNKIA is the name of him Whom we have called the monitor"' of the gods;

Who in heaven and on earth founds for us retreats"' in trouble,

And who allots stations to the Igigi (Sky Spirits) and Anunnaki.

At his name the gods shall tremble and quake in retreat.

(7) ASARULUDU is that name of his Which Amu, his father, proclaimed for him.

He is truly the light of the gods, the mighty leader, Who, as the protecting deities"' of gods

and land, In fierce single combat saved our retreats in distress. Asaruludu, secondly, they have named

(8) NAMTILLAKU,The god who maintains life,"'

Who restored the lost gods, as though his own creation; The lord who revives the dead gods by his pure incantation, Who destroys the wayward foes. Let us praise his prowess!...

Asaruludu, whose name was thirdly called

(9) NAMRU, The shining god who illumines our ways.

Three each of his names"' have Anshar, Lahmu, and Lahamu proclaimed;

Unto the gods, their sons, they did utter them:

"We have proclaimed three each of his names.

Like us, do you utter his names!" joyfully the gods did heed their command,

As in Ubshukinna their exchanged counsels:

"Of the heroic son, our avenger,

Of our supporter we will exalt the name!"

They sat down in their Assembly to fashion"' destinies,

All of them uttering his names in the sanctuary.

(10) ASARU, bestower of cultivation, who established water levels;

Creator of grain and herbs, who causes [vegetation to sprout]."'

(11) ASARUALIM, who is honored in the place of counsel, [who excels in counsel];

To whom the gods hope,"' when pos[sessed of fear]...

Tutu is (14) ZIUKKINNA, life of the host of [the gods], Who established... for the gods the holy heavens; Who keeps a hold on their ways, determines [their courses];

He shall not be forgotten by the beciouded."' Let them [remember]... his deeds!

Tutu they thirdly called

(15) ZIKU, who establishes holiness,

The god of the benign breath, the lord who hearkens and acceeds;

Who produces riches and treasures, establishes abundance;...

Who has turned all our wants to plenty;

Whose benign breath we smelled in sore distress.

Let them speak, let them exalt, let them sing his praises!

Tutu, fourthly, let the people magnify as (16) AGAKU,

The lord of the holy charm, who revives the dead;

Who had mercy on the vanquished gods,

Who removed the voke imposed on the gods, his enemies,

(And) who, to redeem them, created mankind;

The merciful, in whose power it lies to grant life.

May his words endure, not to be forgotten,

In the mouth of the black-headed, whom his hands have created.

Tutu, fifthly, is (I7) TUKU, whose holy spell their mouths shall murmur;

Who with his holy charm has uprooted all the evil ones.

(18) SHAZU, who knows the heart of the gods, Who examines the inside;

From whom the evildoer cannot escape;

Who sets up the Assembly of the gods, gladdens their hearts;

Who subdues the insubmissive; their wide-spread [pro]tection;

Who directs justice, roots [out] crooked talk,

Who wrong and right in his place keeps apart...

(44) IRKINGU, who carried off Kingu in the thick"' of the battle

Who conveys guidance for all, establishes rulership.

(45) KINMA, who directs all the gods, the giver of counsel,

At whose name the gods quake in fear, as at the storm.

(46) ESIZKUR shall sit aloft in the house of prayer;

May the gods bring their presents before him,

That (from him) they may receive their assignments; None can without him create artful works.

Four black-headed ones are among his creatures;... Aside from him no god knows the answer as to their days.

(47) GIBIL, who maintains the sharp point of the weapon,

Who creates artful works in the battle with Tiamat; Who has broad wisdom, is accomplished in insight, Whose mind"-' is so vast that the gods, all of them, cannot fathom (it).

(48) ADDU be his name, the whole sky may he cover.

May his beneficent roar ever hover over

the earth;

May he, as Mummu,"' diminish the clouds;...

Below, for the people may he furnish sustenance.

(49) ASHARU, who, as is his name, guided"' the gods of destiny;

of all the gods is verily in his charge.

(50) NEBIRU shall hold the crossings of heaven and earth;

Those who failed of crossing above and below,

Ever of him shall inquire.

Nebiru is the star... which in the skies is brilliant.

Verily, he governs their turnings,"' to him indeed they look,

Saying: "He who the midst of the Sea restlessly crosses,

Let 'Crossing' be his name, who controls... its midst.

May they uphold the course of the stars of heaven;

May he shepherd all the gods like sheep.

May he vanquish Tiamat; may her life be strait and short!...

Into the future of mankind, when days have grown old,

May she recede... without cease and stay away forever.'

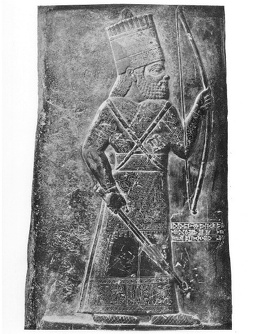

Marduk relief

Psalm to Marduk: Poem of the Righteous Sufferer

Tablet 1 of Poem of the Righteous Sufferer reads:

I will praise the lord of Wisdom, solicitous god,

Furious in the night, calming in the daylight;

Marduk! lord of wisdom, solicitous god,

Furious in the night, claiming in the daylight;

Whose anger engulfs like a tempest,

Whose breeze is sweet as the breath of morn

In his fury not to be withstood, his rage the deluge,

Merciful in his feelings, his emotions relenting.

The skies cannot sustain the weight of his hand,

His gentle palm rescues the moribund.

Marduk! The skies cannot sustain the weight of his hand,

His gentle palm rescues the moribund.

When he is angry, graves are dug,

His mercy raised the fallen from disaster.

When he glowers, protective spirits take flight,

[Source: Foster, Benjamin R. (1995) “Before the Muses: myths, tales and poetry of Ancient Mesopotamia,” CDL Press, Bethesda, Maryland, piney.com]

He has regard for and turns to the one whose god has forsaken him.

Harsh is his punishments, he.... in battles

When moved to mercy, he quickly feels pain like a mother in labor.

He is bull-headed in love of mercy

Like a cow with a calf, he keeps turning around watchfully.

His scourge is barbed and punctures the body,

His bandages are soothing, they heal the doomed.

He speaks and makes one incur many sins,

On the day of his justice sin and guilt are dispelled.

He is the one who makes shivering and trembling,

Through his sacral spell chills and shivering are relieved.

Who raises the flood of Adad, the blow of Erra,

Wh reconciles the warthful god and goddess

The Lord divines the gods´ inmost thoughts

But no god understand his behavior,

Marduk divines the gods´s inmost thoughts

But no god understand his behavior!

As heavy his hand, so compassionate his heart

As brutal his weapons, no life-sustaining his feelings,

Without his consent, who could cure his blow?

Against his will, who could sin and escape?

I will proclaim his anger, which runs deep, like a fish,

He punished me abruptly, then granted life

I will teach the people, I will instruct the land to fear

To be mindful of him is propitious for ......

After the Lord changed day into night

And the warrior Marduk became furious with me,

My own god threw me over and disappeared,

My goddess broke rank and vanished

He cut off the benevolent angel who walked beside me

My protecting spirit was frightened off, to seek out someone else

My vigor was taken away, my manly appearance became gloomy,

My dignity flew off, my cover leaped away.

Terrifying signs beset me

I was forced out of my house, I wandered outside,

My omens were confused, they were abnormal every day,

The prognostication of diviner and dream interpreter could not explain what I was undergoing.

What was said in the street portended ill for me,

When I lay down at nights, my dream was terrifyng

The king, incarnation of the gods, sun of his people

His heart was enraged with me and appeasing him was impossible

Courtiers were plotting hostile against me,

They gathered themselves to instigate base deeds:

If the first !I will make him end his life"

Says the second "I ousted him from his command"

So likewise the third "I will get my hands on his post!"

"I will force his house!" vows the fourth

As the fifth pants to speak

Sixth and seventh follow in his train!" (literally in his protective spirit)

The clique of seven have massed their forces,

Merciless as fiends, equal to demons.

So one is hteir body, united in purpose,

Their hearts fulminate against me, ablaze like fire.

Slander and lies they try to lend credence against me...

NABU (NEBO) , MARDUK’S CLOSE ASSOCIATE

Nebo

Nebo was a close associate of Marduk. Nebo was the city-god of Borsippa, a town across the Euphrates from Babylon. Over time Nebo rose into prominence and attained honors almost equal to those of Marduk, and the twin cities of Babylon and Borsippa acquired almost inseparable gods.

Morris Jastrow said: “Opposite Babylon lies the famous town of Borsippa, designated in the inscriptions as “the city of the Euphrates,” which, as may be concluded from the name and from other indications, appears to be an older settlement than Babylon itself, and to have assumed earlier a position of importance as an intellectual and religious centre. When, however, Hammurabi raised Babylon to be the capital of his empire, Borsippa was obliged to yield its prerogatives, and gradually sank to the rank of a mere dependency upon Babylon—a kind of suburb to the capital city. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The patron deity of Borsippa was a god known as Nebo, whose cult appears at one time to have been carried over into Babylon—perhaps before Marduk became the patron deity of the place. Marduk, however, replaces Nebo as Enlil replaced Ninib; but, just as at Nippur the older sun cult does not disappear, and Ninib becomes the son of Enlil, so the Nebo cult at Babylon is maintained, and Nebo is viewed as the son of Marduk. In both places, therefore, the “father” god appears to be the intruder who sets aside an older chief deity. The combination of Marduk and Nebo, expressed in these terms of relationship, continues to the end of the Babylonian empire. Nebo has a sanctuary within the temple area of Esagila at Babylon which bears the same name, Ezida, “the true house,” as the one given to Nebo’s temple at Borsippa. In return, Marduk has an Esagila, a “lofty house,” in Borsippa. In the Assyrian and later Babylonian periods the two names, Esagila and Ezida, are generally found in combination, as though inseparable in the minds of the Babylonians. Similarly, the two gods, Marduk and Nebo, are quite commonly invoked together, e.g., in the formula of greeting at the beginning of official letters, which, even in the case of the correspondence of the Assyrian monarchs, begin: “May Nebo and Marduk bless the king my lord!” “Who was this god Nebo? The question is not easy to answer, though the most satisfactory view is to regard him as a counterpart of Ea. Like Ea, he is the embodiment and source of wisdom. The art of writing—and therefore of all literature—is more particularly associated with him. A common form of his name designates him as the “god of the stylus,” and his symbol on Boundary Stones is likewise the stylus of the scribes. He was regarded by the Assyrians also as the god of writing and wisdom, and Ashurbanapal, in the colophons to the tablets of his library, names Nebo and his consort Tashmit as the pair who instructed the king to preserve and collect the literary remains of the past. The study of the heavens formed part of the wisdom which is traced back to Nebo; and the temple school at Borsippa became one of the chief centres for the astrological and, subsequently, for the astronomical lore of Babylonia. The archives of that school in fact formed one of the chief resources for the scribes of Ashurbanapal, though the archives at Babylon were also largely drawn upon. In the Persian and Greek periods the school of Borsippa is frequently mentioned in colophons attached to school texts of various kinds, and it is not improbable that the school survived the one at Babylon.

“Like Ea, Nebo is also associated with the irrigation of the fields and with their consequent fertility. A hymn praises him as the one who fills the canals and the dikes, who protects the fields and brings the crops to maturity. From such phrases the conclusion has been drawn by some scholars that Nebo was originally a solar deity, like Marduk, but his traits as a god of vegetation can be accounted for on the supposition that he was a water-deity, like Ea, whose favour was essential to rich harvests. We may, however, also assume that the close partnership between him and Marduk had as a consequence a transfer of some of the father Marduk’s attributes as a solar deity to Nebo, his son, just as Ea passed his traits on to his son, Marduk. Although he is called upon to heal, Nebo plays no part in the incantation-ritual, which revolves, as we shall see, around two ideas—water, represented by Ea, and fire, represented by the fire-god Gibil or Nusku. The predominance of the Ea ritual in incantations left no room for a second water-deity— there was place only for Marduk as an intermediary between Ea and suffering mankind. We may, therefore, rest content with the conclusion that Nebo, like Marduk, belongs to the Eridu group of deities, that, as a counterpart to Ea, his duty was always of a secondary character, and that, with the growing importance of the Marduk cult, he becomes an adjunct to Marduk. This relationship is expressed by making Nebo the son of Marduk. The two pass down through the ages as an inseparable pair—representing a duality, and forming a parallel to that constituted by Ea and Marduk.

“Marduk and Nebo sum up, again, the two chief Powers of nature conditioning the welfare of the country—the sun and the watery element— precisely as do Ea and Marduk; with these latter, however, for reasons that have been given, the order is reversed, just as we have the double order, Anu and Enlil—sun and storm—by the side of Enlil and Ninib—storm and sun. The name Nebo designates the god as a “proclaimer,” while another sign with which his name is commonly written describes him as an artificer or creator. No doubt in his seat of worship, Borsippa, Nebo was at one time looked upon as the creator of the universe, just as Ea, Enlil, Ninib, and Marduk were so regarded in their respective centres. He is portrayed as holding the “tablets of fate” on which the destinies of individuals are inscribed. As “writer” or “scribe” among the gods, he records their decisions, as proclaimer or herald, he announces these decisions. Such functions point to his having occupied from an early period the position of an intermediary, and we are probably not wrong in supposing that the god whose orders he carries out was originally Ea, who was later replaced in this capacity by Marduk. Nebo could, however, retain his attributes as the god of writing without injury to the dignity and superiority of Marduk, for in the ancient Orient, as in the Orient of to-day, the kdtib or scribe is not a person of superior rank. Authorship was at no time in the ancient Orient a basis for social or political prestige. A writer was essentially a secretary who acted as an intermediary.

“The rank that Nebo holds in the systematised pantheon is due, therefore, almost entirely to his partnership with Marduk, and it is interesting to note that the Assyrian kings avail themselves of this association occasionally to play off Nebo, as it were, against Marduk. Some of them appear to pay their homage to Nebo rather than to Marduk, because the latter was in a measure a rival to the head of the Assyrian pantheon. Adad-nirari IV. (810-782 B.C.) goes so far in his adoration of Nebo as to inscribe on a statue of this god (or is it his own statue?): “Trust in Nebo! Trust in no other god !” The Nebo cult, which, like that of other gods, had its ebb and flow, must have enjoyed a special popularity in Assyria in the 9th century.”

Marduk Versus Nebo

ruins of the ziggurat and temple of Nebu in Borsippa

Morris Jastrow said: “No such rivalry between the Marduk and Nebo cults appears ever to have existed in Babylonia, though it is perhaps not without significance that in the days of the neo-Babylonian empire no less than three of the rulers bear names in which Nebo enters as one of the elements. The position of Marduk was, however, at all times too strong to be seriously affected by fashions in names or changes in the cult. He not only remains during all periods after Hammurabi the head of the pantheon, but as the ages rolled on he absorbed, as has already been pointed out, the attributes of all the great gods of the pantheon. He becomes the favourite of the gods as well as of men. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“Starting out at Babylon with the absorption of the character of Ea, combining in his person the two Powers, water and the sun, which comprise so large a share of divine government and control of the universe, he ends by taking over also the duties of Enlil of Nippur. This is of the greatest significance. It argues for the boldness of the Marduk priests and for the security of Marduk’s position that they gave to Marduk the title that was so long the prerogative of Enlil, to wit, bel, “the lord” paramount. The old nature-myths are once more adopted by the priests of Marduk and transformed so as to give to Marduk the central position. It is he who seizes the tablets of fate from the Zu bird—the personification of some solar deity,—and henceforth holds the destiny of mankind in his hands.

“The creation-myth is transformed into a paeon celebrating the deeds of Marduk. What in one version was ascribed to Anu, in another to Ninib, in a third to Enlil, and in a fourth to Ea, is in the Babylon version ascribed to Marduk. Two series of creation-stories are combined; one embodying an account of a conflict with a monster, the symbol of primaeval chaos, the other a story of rebellion against Ea which is successfully quelled. In the first group we can distinguish three versions, one originating at Uruk in which the solar god Anu becomes the conqueror of Tiamat, the other two originating at Nippur, an earlier one in which the solar god Ninib takes the part assigned, in the Uruk version, to Anu, and a later one in which Enlil replaces Ninib. The character of the myth is thereby changed. Instead of symbolising the triumph of the sun of the springtime over the storms of winter, it becomes an illustration of the subjugation of chaos by the rise of law and order in the universe.

Marduk, Nebo, Creation and Monotheism

Morris Jastrow said: “In the Babylon or Marduk version, Anu is at first dispatched by the gods against the monster but is frightened at the sight of her. All the other gods, too, are in mortal terror of Tiamat but Marduk offers to proceed against her on condition that in case of his triumph the entire assemblage of the gods shall pay him homage and acknowledge his sway. The compact is accepted, and Marduk arms himself for the fray. The weapons that he takes— the four winds and the various storms, the tempest, the hurricane, and tornado—symbolise his absorption of the part of Enlil, the god of storms. Marduk meets Tiamat, and dispatches her by inflating her with an evil wind, and then bursting her open with his lance. The gods rejoice and give him their names, a procedure which, according to the views of antiquity, is equivalent to bestowing upon him their essence and their attributes.[Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“After all the gods have thus done, Enlil advances and hails Marduk as bêl mâtâti, “lord of lands,” which was one of Enlil’s special names, and finally Ea solemnly declares that Marduk’s name shall also be Ea]: “He who has been glorified by his fathers, He shall be as I am—Ea be his name!” The purpose of the story is evident. All the religious centres pay homage to Babylon—the seat of the Marduk cult; Marduk absorbs the attributes and powers of all the other gods.

“In the schools this prominence of Marduk as a reflection of the political supremacy of Babylon is still further developed, and finds a striking expression in a fragment of composition preserved for us by a fortunate chance:

Ea is the Marduk of canals;

Ninib is the Marduk of strength;

Nergal is the Marduk of war;

Zamama is the Marduk of battle;

Enlil is the Marduk of sovereignty and control;

Nebo is the Marduk of possession;

Sin is the Marduk of illumination of the night;

Shamash is the Marduk of judgments;

Adad is the Marduk of rain;

Tishpak is the Marduk of the host;

Gal is the Marduk of strength;

Shukamunu is the Marduk of the harvest.

“From this text, scholars have drawn the conclusion that the Babylonian religion resulted in a monotheistic conception of the universe. Is this justified? In so far as Marduk absorbs the characters of all the other gods, there is no escape from this much of the conclusion:—there was a tendency towards monotheism in the Euphrates Valley, as there was at one time in Egypt. On the other hand, it must be borne in mind that similar lists were drawn up by priests. They reveal the speculations of the temple-schools rather than popular beliefs, but even when thus viewed, their aim was probably to go no farther than to illustrate in a striking manner the universality of the god’s nature so as to justify his position at the head of the pantheon. This position was emphasised in an equally striking manner by the ceremonies of New Year’s day, when a formal assembly of the gods was held in a special shrine in Babylon, close by the temple area, with all the chief gods grouped about Marduk, (just as the princes, governors, and generals stand about the king), paying homage to him as their chief, and deciding in solemn state the fate of the country and of individuals for the coming year.

“The Babylonian priest could re-echo the ecstatic cry of the Psalmist (Ps. lxxxvi., 8) — “There is none like thee among the gods, O Lord, And there is nothing like thy works” — with this important difference, however, that, in the mind of the Hebrew poet, Jahweh was the only power that had a real existence, whereas to the Babylonian priest Marduk was merely the first and highest in the divine realm. Still, that the other gods are merely manifestations of Marduk (a fair implication of the list) is a thought which not improbably presented itself to some of the choicer minds among the priests, though it remained without practical consequences. A certain tendency toward a monotheistic conception of the universe is after all no unusual phenomenon, nor is monotheism in itself necessarily, the outcome of a deep religious spirit— it may sometimes be the product of rationalistic speculation. In many a Babylonian composition the term ilu, “god,” is used in a manner to convey the impression that there was only one god to be appealed to. Greek and Roman writers often speak of 0so<; and deus in much the same way as we ourselves do; and even among people on a low level of culture we are constantly surprised by indications that, albeit in a faint and imperfect manner, the thought occurs that all nature is the manifestation of a single Power, though generally not a Power to be directly approached. The distinctive feature of Hebrew monotheism is its consistent adherence to the principle of a transcendent deity, and of the reorganisation of the cult in obedience to this principle. No attempt was made at any time in Babylonia and Assyria to set aside the cult of other gods in favour of Marduk. On the contrary, side by side with the Marduk cult in Babylonia and with the cult of Ashur in Assyria, we find down to the latest period all— Sin, Shamash, Nebo, Ninib, Nergal, Adad, Ishtar —receiving in their special shrines the homage which tradition and long established ritual had prescribed.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024