Home | Category: Religion / Deities

MESOPOTAMIAN DEITIES

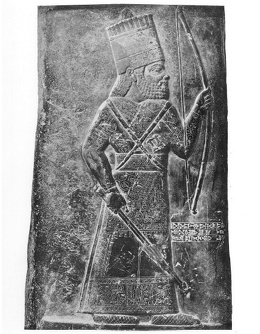

Ashur, the main god of Assyria

Ira Spar of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Unlike some later monotheistic religions, in Mesopotamian mythology there existed no systematic theological tractate on the nature of the deities. Examination of ancient myths, legends, ritual texts, and images reveals that most gods were conceived in human terms. They had human or humanlike forms, were male or female, engaged in intercourse, and reacted to stimuli with both reason and emotion. Being similar to humans, they were considered to be unpredictable and oftentimes capricious. Their need for food and drink, housing, and care mirrored that of humans. Unlike humans, however, they were immortal and, like kings and holy temples, they possessed a splendor called melammu. Melammu is a radiance or aura, a glamour that the god embodied. It could be fearsome or awe inspiring. Temples also had melammu. If a god descended into the Netherworld, he lost his melammu. Except for the goddess Inanna (Ishtar in Akkadian), the principal gods were masculine and had at least one consort. Gods also had families.[Source: Spar, Ira. "Mesopotamian Deities", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Unlike some later monotheistic religions, in Mesopotamian mythology there existed no systematic theological tractate on the nature of the deities. Examination of ancient myths, legends, ritual texts, and images reveals that most gods were conceived in human terms. They had human or humanlike forms, were male or female, engaged in intercourse, and reacted to stimuli with both reason and emotion. Being similar to humans, they were considered to be unpredictable and oftentimes capricious. Their need for food and drink, housing, and care mirrored that of humans. Unlike humans, however, they were immortal and, like kings and holy temples, they possessed a splendor called melammu. Melammu is a radiance or aura, a glamour that the god embodied. It could be fearsome or awe inspiring. Temples also had melammu. If a god descended into the Netherworld, he lost his melammu. Except for the goddess Inanna (Ishtar in Akkadian), the principal gods were masculine and had at least one consort. Gods also had families.” \^/

RELATED ARTICLES:

MESOPOTAMIAN DEMONS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

IMPORTANT MESOPOTAMIAN DEITIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

BABYLONIAN DEITIES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Sumerian Gods and Their Representations” by Irving L. Finkel, Markham J. Geller (1997) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary” by Jeremy Black (1992) Amazon.com;

“Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer” by Diane Wolkstein (1983) Amazon.com;

“A Handbook of Gods and Goddesses of the Ancient Near East: Three Thousand Deities of Anatolia, Syria, Israel, Sumer, Babylonia, Assyria, and Elam” by Douglas R. Frayne , Johanna H. Stuckey, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion” by Thorkild Jacobsen (1976) Amazon.com;

“Anunnaki Gods: The Sumerian Religion” by Joshua Free Amazon.com;

“A Handbook of Ancient Religions” by John R. Hinnells (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture” by Francesca Rochberg Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography” by Wayne Horowitz (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Social World of the Babylonian Priest” by Bastian Still (2019) Amazon.com

Sumerian Spiritual World

The Sumerian had no conception of what we mean by a god. The supernatural powers he worshipped or feared were spirits of a material nature. Every object had its zi, or “spirit,” which accompanied it like a shadow, but unlike a shadow could act independently of the object to which it belonged. The forces and phenomena of nature were themselves “spirits;” the lightning which struck the temple, or the heat which parched up the vegetation of spring, were as much “spirits” as the zi, or “spirit,” which enabled the arrow to reach its mark and to slay its victim. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900][Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

When contact with the Semites had introduced the idea of a god among the Sumerians, it was still under the form of a spirit that their powers and attributes were conceived. The Sumerian who had been unaffected by Semitic teaching spoke of the “spirit of heaven” rather than of the god or goddess of the sky, of the “spirit of Ea” rather than of Ea himself, the god of the deep. Man, too, had a zi, or “spirit,” attached to him; it was the life which gave him movement and feeling, the principle of vitality which constituted his individual existence. In fact, it was the display of vital energy in man and the lower animals from which the whole conception of the zi was derived.

The force which enables the animate being to breathe and act, to move and feel, was extended to inanimate objects as well; if the sun and stars moved through the heavens, or the arrow flew through the air, it was from the same cause as that which enabled the man to walk or the bird to fly. The zi of the Sumerians was thus a counterpart of the ka, or “double,” of Egyptian belief. The description given by Egyptian students of the ka would apply equally to the zi of Sumerian belief. They both belong to the same level of religious thought; indeed, so closely do they resemble one another that the question arises whether the Egyptian belief was not derived from that of ancient Sumer.

Semitic World of Gods

Wholly different was the idea which underlay the Semitic conception of a spiritual world. He believed in a god in whose image man had been made. It was a god whose attributes were human, but intensified in power and action. The human family on earth had its counterpart in the divine family in heaven. By the side of the god stood the goddess, a colorless reflection of the god, like the woman by the side of the man. The divine pair were accompanied by a son, the heir to his father's power and his representative and interpreter. As man stood at the head of created things in this world, so, too, the god stood at the head of all creation. He had called all things into existence, and could destroy them if he chose. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900][Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The Semite addressed his god as Baal or Bel, “the lord.” It was the same title as that which was given to the head of the family, by the wife to the husband, by the servant to his master. There were as many Baalim or Baals as there were groups of worshippers. Each family, each clan, and each tribe had its own Baal, and when families and clans developed into cities and states the Baalim developed along with them. The visible form of Baal was the Sun; the Sun was lord of heaven and therewith of the earth also and all that was upon it.

But the Sun presented itself under two aspects. On the one side it was the source of light and life, ripening the grain and bringing the herb into blossom; on the other hand it parched all living things with the fierce heats of summer and destroyed what it had brought into being. Baal, the Sun-god, was thus at once beneficent and malevolent; at times he looked favorably upon his adorers, at other times he was full of anger and sent plague and misfortune upon them. But under both aspects he was essentially a god of nature, and the rites with which he was worshipped accordingly were sensuous and even sensual.

Evolution of Babylonian Deities

Such were the two utterly dissimilar conceptions of the divine out of the union of which the official religion of Babylonia was formed. The popular religion of the country also grew out of them though in a more unconscious way. The Semite gave the Sumerian his gods with their priests and temples and ceremonies. The Sumerian gave in return his belief in a multitude of spirits, his charms and necromancy, his sorcerers and their sacred books. Unlike the gods of the Semites, the “spirits” of the Sumerian were not moved by human passions. They had, in fact, no moral nature. Like the objects and forces they represented, they surrounded mankind, upon whom they would inflict injury or confer benefits. But the injuries were more frequent than the benefits; the sum of suffering and evil exceeds that of happiness in this world, more especially in a primitive condition of society. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900][Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Sumerian image, maybe a spirit

Hence the “spirits” were feared as demons rather than worshipped as powers of good, and instead of a priest a sorcerer was needed who knew the charms and incantations which could avert their malevolence or compel them to be serviceable to men. Sumerian religion, in fact, was Shamanistic, like that of some Siberian tribes today, and its ministers were Shamans or medicine-men skilled in witchcraft and sorcery whose spells were potent to parry the attacks of the demon and drive him from the body of his victim, or to call him down in vengeance on the person of their enemy.

Shamanism, however, pure and simple, is incompatible with an advanced state of culture, and as time went on the Shamanistic faith of the Sumerians tended toward a rudimentary form of polytheism. Out of the multitude of spirits there were two or three who assumed a more commanding position than the rest. The spirit of the sky, the spirit of the water, and more especially the spirit of the underground world, where the ghosts of the dead and the demons of night congregated together, took precedence of the rest. Already, before contact with the Semites, they began to assume the attributes of gods. Temples were raised in their honor, and where there were temples there were also priests.

This transition of certain spirits into gods seems to have been aided by that study of the heavens and of the heavenly bodies for which the Babylonians were immemorially famous. At all events, the ideograph which denotes “a god” is an eight-rayed star, from which we may perhaps infer that, at the time of the invention of the picture-writing out of which the cuneiform characters grew, the gods and the stars were identical.

Development of Babylonian and Assyrian Gods

Morris Jastrow said: “The religion of Babylonia and Assyria passes, in the course of its long development, through the various stages of the animistic conception of nature towards a concentration of the divine Powers in a few supernatural Beings. Naturally, when our knowledge of the history of the Euphrates Valley begins, we are long past the period when practically all religion possessed by the people was summed up in the personification of the powers of nature, and in some simple ceremonies revolving largely around two ideas, Taboo and Totemism. The organisation of even the simplest form of government, involving the division of the community into little groups or clans, with authority vested in certain favoured individuals, carries with it as a necessary corollary a selection from the various personified powers who make themselves felt in the incidents and accidents of daily life. This selection leads ultimately to the formation of the pantheon. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

Nebo

“The gods that are prominent in the cult of a religion, in both its official and its popular forms, may be defined as the remainder of the large and indefinite number of Powers recognised everywhere by primitive man. While in the early animistic stage of religion the Power or spirit that manifests itself in the life of the tree is put on the same plane with the spirit supposed to reside in a flowing stream, or with the Power that manifests itself in the heat of the sun or in the severity of a storm, repeated experience gradually teaches man to differentiate between such Powers as markedly and almost continuously affect his life, and such as only incidentally force themselves on his notice. The process of selection receives, as has been already intimated, a strong impetus by the creation of little groups, arising from the extension of the family into a community. These two factors, repeated experience and social evolution, while perhaps not the only ones involved, constitute the chief elements in the unfolding of the religious life of a people.

“In the case of the religion of Babylonia and Assyria we find the process of selection leading in the main to the cult of the sun and the moon, of the Power that manifests itself in vegetation, and of the Power that is seen in storms and in bodies of water. Sun, moon, vegetation, storms, and water constitute the forces with which man is brought into frequent, if not constant, contact. Agriculture and commerce being two leading pursuits in the civilisation that developed in the Euphrates Valley, it is natural to find the chief deities worshipped in the various political centres of the earliest period of Babylonian history to be personifications of one or the other of these five Powers. The reasons for the selection of the sun and moon are obvious.

“The two great luminaries of the heavens would appeal to a people even before a stage of settled habitation, coincident with the beginnings of agriculture, would be reached. Even to the homeless nomad the moon would form a guide in his wanderings, and as a measure of time would be singled out among the Powers that permanently and continuously enter into the life of the group and of the individual. With an advance from the lower to the higher nomadic stage, marked by the domestication of animals, with its accompanying pastoral life, the natural vegetation of the meadows would assume a larger importance, while, when the stage is reached when man is no longer dependent upon what nature produces of her own accord but when he, himself, becomes an active partner in the work of nature, his dependency upon the Power that he recognises in the sun would be more emphatically brought home to him. Long experience will teach him how much his success or failure in the tilling of the soil must depend upon the favour of the sun, and of the rains in the storms of the winter season. Distinguishing between the various factors involved in bringing about his welfare, he would reach the conception of a great triad—the sun, the power of vegetation and fertility residing in the earth, and the power that manifests itself in storms and rains.

Mesopotamian Deities, Power and Nature

Ira Spar of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Possessing powers greater than that of humans, many gods were associated with astral phenomena such as the sun, moon, and stars, others with the forces of nature such as winds and fresh and ocean waters, yet others with real animals—lions, bulls, wild oxen—and imagined creatures such as fire-spitting dragons. [Source: Spar, Ira. Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“In the Sumerian hymn "Enlil in the E-Kur," the god Enlil is described as controlling and animating nature: “Without the Great Mountain Enlil . . . the carp would not . . . come straight up[?] from the sea, they would not dart about. The sea would not produce all its heavy treasure, no freshwater fish would lay eggs in the reedbeds, no bird of the sky would build nests in the spacious lands; in the sky, the thick clouds would not open their mouths; on the fields, dappled grain would not fill the arable lands, vegetation would not grow lushly on the plain; in the gardens, the spreading trees of the mountain would not yield fruit. \^/

Nergal

“As supreme figures, the gods were transcendent and awesome, but unlike most modern conceptions of the divine, they were distant. Feared and admired rather than loved, the great gods were revered and praised as masters. They could display kindness, but were also fickle and at times, as explained in mythology, poor decision makers, which explains why humans suffer such hardships in life. \^/

“Generally speaking, gods lived a life of ease and slumber. While humans were destined to lives of toil, often for a marginal existence, the gods of heaven did no work. Humankind was created to ease their burdens and provide them with daily care and food. Humans, but not animals, thus served the gods. Often aloof, the gods might respond well to offerings, but at a moment's notice might also rage and strike out at humans with a vengeance that could result in illness, loss of livelihood, or death.” \^/

Mesopotamian Deities, Politics and Cities

Ira Spar of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Cuneiform tablets as early as the third millennium indicate that the gods were associated with cities. Each community worshipped its city's patron deity in the main temple. The sky god An and his daughter Inanna were worshipped at Uruk; Enlil, the god of earth, at Nippur; and Enki, lord of the subterranean freshwaters, at Eridu. This association of city with deity was celebrated in both ritual and myth. A city's political strength could be measured by the prominence of its deity in the hierarchy of the gods. Babylon, a minor city in the third millennium, had become an important military presence by the Old Babylonian period and its patron deity, noted in a mid-third millennium text from Abu-Salabikh as ranking near the bottom of the gods, rose to become the head of the pantheon when Babylon ascended to military supremacy in the late second millennium. [Source: Spar, Ira. Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

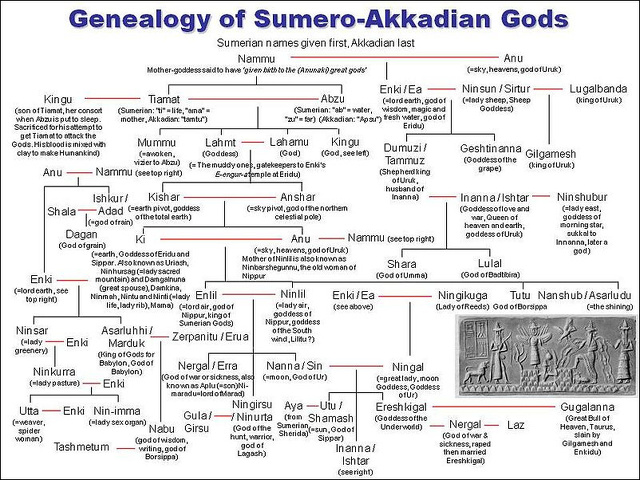

“Political events influenced the makeup of the pantheon. With the fall of Sumerian hegemony at the end of the third millennium, Babylonian culture and political control spread throughout southern Mesopotamia. At the end of the third millennium B.C., Sumerian texts list approximately 3,600 deities. With the fall of Sumerian political might and the rise of the Amorite dynasties at the end of the third millennium and beginning of the second millennium, religious traditions began to merge. \^/

Older Sumerian deities were absorbed into the pantheon of Semitic-speaking peoples. Some were reduced to subordinate status while newer gods took on the characteristics of older deities. The Sumerian god An became the Semitic Anu, while Enki became Ea, Inanna became Ishtar, and Utu became Shamash. As Enlil, the supreme Sumerian god, had no counterpart in the Semitic pantheon, his name remained unchanged. Most of the lesser Sumerian deities now faded from the scene. At the end of the second millennium, the Babylonian myth "Enuma Elish" refers to only 300 gods of the heavens. In this process of associating Semitic gods with political supremacy, Marduk surpassed Enlil as chief of the gods and, according to "Enuma Elish," Enlil gave Marduk his own name so that Marduk now became "Lord of the World." Similarly, Ea, the god of the subterranean freshwaters, says of Marduk in the same myth, "His name, like mine, shall be Ea. He shall provide the procedures for all my offices. He shall take charge of all my commands." \^/

Babylonian and Assyrian Gods and the Climate of Mesopotamia

Shamash

Morris Jastrow said: ““All this applies with peculiar force to the climate of the Euphrates Valley, with its two seasons, the rainy and the dry, dividing the year. The welfare of the country depended upon the abundant rains, which, beginning in the late fall, continued uninterruptedly for several months, frequently accompanied by thunder, lightning, and strong winds. In the earliest period to which we can trace back the history of the Euphrates Valley we find entire districts covered with a network of canals, serving the double purpose of avoiding the destructive floods occasioned by the overflow of the Euphrates and the Tigris, and of securing a more direct irrigation of the fields. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“To the sun, earth, and storms there would thus be added, as a fourth survival from the animistic stage, the Power residing in the two great streams, and in the Persian Gulf, which to the Babylonians was the “Father of Waters.” Commerce, following in the wake of agriculture, would lend an additional importance to the watery element as a means of transportation, and the sense of this importance would find a natural expression in the cult of water deities. While the chief gods of the pantheon thus evolved are identical with the Powers or spirits that belong to the animistic stage of religion, we may properly limit the designation “deities” to that period in the development of the religious life with which we are here concerned and which represents, to emphasise the point once more, a natural selection of a relatively small number out of a promiscuous and almost unlimited group of Powers.

“It is perhaps more or less a matter of accident that we find in one of the centres of ancient Babylonia the chief deity worshipped as a sun-god, in another as a personification of the moon, and in a third as the goddess of the earth. We have, however, no means of tracing the association of ideas that led to the choice of Shamash, the sun-god, as the patron deity of Larsa and Sippar, the moon-god Sin as patron of Ur and Harran, and Ishtar, the great mother-goddess, the personification of the power of vegetation in the earth and of fertility among animals and mankind, as the centre of the cult in Uruk. On the other hand, we can follow the association of ideas that led the ancient people of the city of Eridu, lying at one time at or near the mouth of the Persian Gulf, to select a water deity known as Ea as the patron deity of the place. In the case of the most important of the storm deities, Enlil or Ellil, associated with the city of Nippur, we can also follow the process that resulted in this association; but this process is of so special and peculiar a character that it merits to be set forth in ampler detail.

Mesopotamian Hierarchy of Deities

Ira Spar of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Beginning in the second millennium B.C., Babylonian theologians classified their major gods in a hierarchical numerical order. Anu was represented by the number 60, Enlil by 50, Ea by 40, Sin, the moon god, by 30, Shamash by 20, Ishtar by 15, and Adad, the god of storms, by 6.” [Source: Spar, Ira. Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

Morris Jastrow said: “Anu, Enlil, Ea, presiding over the universe, are supreme over all the lower gods and spirits combined as Annunaki and Igigi, but they entrust the practical direction of the universe to Marduk, the god of Babylon. He is the first-born of Ea, and to him as the worthiest and fittest for the task, Anu and Enlil voluntarily commit universal rule. This recognition of Marduk by the three deities, who represent the three divisions of the universe—heaven, earth, and all waters,—marks the profound religious change that was brought about through the advance of Marduk to a commanding position among the gods. From being a personification of the sun with its cult localised in the city of Babylon, over whose destinies he presides, he comes to be recognised as leader and director of the great Triad. Corresponding, therefore, to the political predominance attained by the city of Babylon as the capital of the united empire, and as a direct consequence thereof, the patron of the political centre becomes the head of the pantheon to whom gods and mankind alike pay homage. The new order must not, however, be regarded as a break with the past, for Marduk is pictured as assuming the headship of the pantheon by the grace of the gods, as the legitimate heir of Anu, Enlil, and Ea. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“There are also ascribed to him the attributes and powers of all the other great gods, of Ninib, Shamash, and Nergal, the three chief solar deities, of Sin the moon-god, of Ea and Nebo, the chief water deities, of Adad, the storm-god, and especially of the ancient Enlil of Nippur. He becomes like Enlil “the lord of the lands,” and is known pre-eminently as the bel or “lord.” Addressed in terms which emphatically convey the impression that he is the one and only god, whatever tendencies toward a true monotheism are developed in the Euphrates Valley, all cluster about him.

“The cult undergoes a correspondingly profound change. Hymns, originally composed in honour of Enlil and Ea, are transferred to Marduk. At Nippur, as we shall see, there developed an elaborate lamentation ritual for the occasions when national catastrophes, defeat, failure of crops, destructive storms, and pestilence revealed the displeasure and anger of the gods. At such times earnest endeavours were made, through petitions, accompanied by fasting and other symbols of contrition, to bring about a reconciliation with the angered Powers. This ritual, owing to the religious preeminence of Nippur, became the norm and standard throughout the Euphrates Valley, so that when Marduk and Babylon came practically to replace Enlil and Nippur, the formulas and appeals were transferred to the solar deity of Babylon, who representing more particularly the sun-god of spring, was well adapted to be viewed as the one to bring blessing and favours after the sorrows and tribulations of the stormy season, which had bowed the country low.

“Just as the lamentation ritual of Nippur became the model to be followed elsewhere, so at Eridu, the seat of the cult of Ea, the water deity, an elaborate incantation ritual was developed in the course of time, consisting of sacred formulas, accompanied by symbolical rites for the purpose of exorcising the demons that were believed to be the causes of disease and of releasing those who had fallen under the power of sorcerers. The close association between Ea and Marduk (the cult of the latter, as will be subsequently shown, having been transferred from Eridu to Babylon), led to the spread of this incantation ritual to other parts of the Euphrates Valley. It was adopted as part of the Marduk cult and, as a consequence, the share taken by Ea therein was transferred to the god of Babylon. This adoption, again, was not in the form of a violent usurpation by Marduk of functions not belonging to him, but as a transfer willingly made by Ea to Marduk, as his son.

“In like manner, myths originally told of Enlil of Nippur, of Anu of Uruk, and of Ea of Eridu, were harmoniously combined, and the part of the hero and conqueror assigned to Marduk. Prominent among these myths was the story of the conquest of the winter storms, pictured as chaos preceding the reign of law and order in the universe. In each of the chief centres the character of creator was attributed to the patron deity, thus in Nippur to Enlil, in Uruk to Anu, and in Eridu to Ea. The deeds of these gods were combined into a tale picturing the steps leading to the gradual establishment of order out of chaos, with Marduk as the one to whom the other gods entrusted the difficult task. Marduk is celebrated as the victor over Tiamat—a monster symbolising primeval chaos. In celebration of his triumph all the gods assemble in solemn state, and address him by fifty names,—a procedure which in ancient phraseology means the transfer of all the attributes involved in these names. The name is the essence, and each name spells additional power. Anu hails Marduk as “mightiest of the gods,” and, finally, Enlil and Ea step forward and declare that their own names shall henceforth be given to Marduk. “His name,” says Ea, “shall be Ea as mine,” and so once more the power of the son is confirmed by the father.

Images and Symbols of Mesopotamian Deities

Ira Spar of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “From about the middle of the third millennium B.C., many deities were depicted in human form, distinguished from mortals by their size and by the presence of horned headgear. Statues of the gods were mainly fashioned out of wood, covered with an overleaf of gold, and adorned with decorated garments. [Source: Spar, Ira. Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The goddess Inanna wore a necklace of lapis lazuli and, according to the myth "The Descent of Ishtar into the Netherworld," she was outfitted with elaborate jewelry. Texts refer to chests, the property of the god, filled with gold rings, pendants, rosettes, stars, and other types of ornaments that could adorn their clothing. Statues were not thought to be actual gods but were regarded as being imbued with the divine presence. Being humanlike, they were washed, dressed, given food and drink, and provided with a lavishly adorned bedchamber. \^/

“Deities could also be represented by symbols or emblems. Some divine symbols, such as the dagger of the god Ashur or the net of Enlil, were used in oath-taking to confirm a declaration. Divine symbols appear on stelae and naru (boundary stones) representing gods and goddess. Marduk, for example, the patron deity of Babylon, was symbolized with a triangular-headed spade; Nabu, the patron of writing, by a cuneiform wedge; Sin, the moon god, had a crescent moon as his symbol; and Ishtar, the goddess of heaven, was represented by a rosette, star, or lion.” \^/

Symbols of the Gods on Boundary Stones

Boundary Stones with symbols of the gods include one from the reign gf the Kassite King Nazi-maruttash (c. 1320 B.C.) found at Susa and now in the Louvre. Morris Jastrow said: “The symbols shown on Face D are: in the uppermost row, Anu and Enlil, symbolised by shrines with tiaras; in the second row—probably Ea [shrine with goat-fish and ram’s head ], and Ninlil (shrine with symbol of the goddess); third row—spear-head of Marduk, Ninib (mace with two lion heads); Zamama (mace with vulture head); Nergal (mace with lion's head); fourth row, Papsukal (bird on pole), Adad (or Ranunan—lightning fork on back of crouching ox); running along side of stone, the serpen t-god, Siru. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“On Face C are the symbols of Sin, the moon-god (crescent); Shamash the sun-god (solar disc); Ishtar (eight-pointed star); goddess Gula sitting on a shrine with the dog as her animal at her feet; Ishkhara (scorpion); Nusku, thefire-god (lamp). “The other two faces (A and B) are covered with the inscription. Nineteen gods are mentioned at the dose of the inscription, where these gods are called upon to curse any one who defaces or destroys the stone, or interferes with the provisions contained in the inscription.

Another boundary stone of which two faces are shown is dated in the reign of Marduk-baliddin, King of Babylonia (c. 1170 B.C.) and was found at Susa and now in the Louvre. The symbols shown in the illustration are: Zamama (mace with the head of a vulture); Nebo (shrine with four rows of bricks on it, and homed dragon in front of it); Ninib (mace with two lion heads); Nusku, the god of fire Gamp); Marduk (spear-head); Bau (walking bird); Papsukal (bird perched on pole); Anu and Enlil (two shrines with tiaras); Sin, the moon-god (crescent). In addition there are Ishtar (eight-pointed star),nShamash (sun disc), Ea (shrine with ram's head on it and goat-fish before it), Gula (sitting dog), goddess Ishkhara (scorpiqn), Nergal (mace with lion head), Adad (or Ramman—crouching ox with lightning fork on bade), Sim—the serpent god (coiled serpent on top of stone).

“All these gods, with the exception of the last named, are mentioned in the curses at the close of the inscription together with their consorts. In a number of cases, (e. g., Shamash, Nergal, and Ishtar) minor deities of the same character are added which came to be regarded as forms of these deities or as their attendants; and lastly some additional gods notably Tammuz (under the form Damu), his sister Geshtin-Anna (or belit seri), and the two Kassite deities Shukamuna and Shumalia. In all forty-seven gods and goddesses are enumerated which may, however, as indicated, be reduced to a comparatively small number.”

Female Consorts of Mesopotamia Gods

Morris Jastrow said: “While every male god of the pantheon had a consort, these goddesses had but a comparatively insignificant share in the cult. In many cases, they have not even distinctive names but are merely the counterpart of their consorts, as Nin-lil, “lady of the storm,” by the side of En-lil, “lord of the storm,” or still more indefinitely as Nin-gal, “the great lady,” the consort of the moon-god Sin, or as Dam-kina, “the faithful spouse,” the female associate of Ea, or as Shala, “the lady” paramount, the consort of Adad. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“In other cases they are specified by titles that furnish attributes reflecting the traits of their consorts, as Sarpanit, “the brilliantly shining one,” the common designation of the consort of Marduk—clearly an allusion to the solar quality of Marduk himself,—or as Tashmit, “obedience,” the consort of Nebo—plausibly to be explained as reflecting the service which Nebo, as son, owes to his father and superior, Marduk. In the case of Anu we find his consort designated by the addition of a feminine ending to his name. As Antum, this goddess is merely a pale reflection of her lord and master. Somewhat more distinctive is the name of the consort of Ninib, Gula, meaning “great one.” This, at least, emphasises the power of the goddess, though in reality it is Ninib to whom “greatness” attaches, while Gula, or Bau, as she is also termed, shines by reflected glory.

“In all these instances it is evident that the association of a female counterpart with the god is merely an extension to the circle of the gods of the social customs prevalent in human society; and the inferior rank accorded to these goddesses is, similarly, due to the social position assigned in the ancient Orient to woman, who, while enjoying more rights than is ordinarily supposed, is yet, as wife, under the complete control of her husband—an adjunct and helpmate, a junior if not always a silent partner, her husband’s second self, moving and having her being in him.

“But by the side of these more or less shadowy consorts there is one goddess who occupies an exceptional position, and even in the oldest historical period has a rank equal to that of the great gods. Appearing under manifold designations, she is the goddess associated with the earth, the great mother-goddess who gives birth to everything that has life—animate and inanimate. The conception of such a power clearly rests on the analogy suggested by the process of procreation, which may be briefly defined as the commingling of the male and female principles. All nature, constantly engaged in the endeavour to reproduce itself, was thus viewed as a result of the combination of these two principles. On the largest scale sun and earth represent such a combination. The earth bringing forth its infinite vegetation was regarded as the female principle, rendered fruitful by the beneficent rays of the sun. “Dust thou art and unto dust shalt thou return” illustrates the extension of this analogy to human life, which in ancient myths is likewise represented as springing into existence from mother-earth. It is, therefore, in centres of sun-worship, like that of Uruk, where we find the earliest traces of the distinctive personality of a mother-goddess. To this ancient centre we can trace the distinctive name, Ishtar, as the designation of this goddess, though even at Uruk, she is more commonly indicated by a vaguer title, Nana, which conveys merely the general idea of “lady.” The opening scene of the great national epic of Babylonia, known as the adventures of Gilgamesh, is laid in Uruk, which thus appears as the place in which the oldest portion of the composite tale originated.

Sun Gods in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “Whatever the reasons that led to this concentration of all the unfavourable phases of the sun-god on Nergal, the prominence that the cult of Babbar (or Shamash) at Sippar acquired was certainly one of the factors involved. This cult cannot be separated from that at Larsa. The designation of the god at both places is the same, and the name of the chief sanctuary of the sun-god at both Larsa and Sippar is E-Babbar (or E-Barra), “the shining house.” The cult of Babbar was transferred from the one place to the other, precisely as Marduk’s worship was carried from Eridu to Babylon. While Larsa appears to be the older of the two centres, Sippar, from the days of Sargon onward, begins to distance its rival, and, in the days of Hammurabi, it assumes the character of a second capital, ranking immediately after Babylon, and often in close association with that city. Even the cult of Marduk could not dim the lustre of Shamash at Sippar. During the closing days of the neo-Babylonian empire, the impression is imparted that there was, in fact, some rivalry between the priests of Sippar and those of Babylon. Nabonnedos, the last king of Babylonia, is described as having offended Marduk by casting his lot in with the adherents of Shamash, so that when Cyrus enters the city he is hailed as the saviour of Marduk’s prestige and received with open arms by the priests of Babylon. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

Shamash

“The original solar character of Marduk, we have seen, was obscured by his assuming the attributes of other deities that were practically absorbed by him, but in the case of Shamash at Sippar no such transformation of his character took place. He remains throughout all periods the personification of the beneficent power residing in the sun. The only change to be noted as a consequence of the pre-eminence of the cult at Sippar is that the sun-god of this place, absorbing in a measure many of the minor localised sun-cults, becomes the paramount sun-god, taking the place occupied in the older Babylonian pantheon by Ninib of Nippur. The Semitic name of the god—Shamash— becomes the specific term for the sun, not only in Babylonia but throughout the domain of the Semites and of Semitic influence.

“A place had, however, to be found for sun-cults at centres so important that they could not be absorbed even by Shamash of Sippar. Nippur retained its religious prestige throughout all vicissitudes, and its solar patron was regarded in the theological system as typifying more particularly the sun of the springtime; wThile at Cuthah Nergal was pictured as the sun of midsummer with all the associations connected with that trying season. The differentiation had to a large extent a purely theoretical import. The practical cult was not affected by such speculations and no doubt, at Cuthah itself, Nergal was also worshipped as a beneficent power. On the other hand, Ninib, as a survival of the period when he was the “Shamash” of the entire Euphrates Valley, is also regarded, like Nergal, as a god of war and of destruction along with his beneficent manifestations. In ancient myths dealing with his exploits his common title is “warrior,” and the planet Saturn, with which he is identified in astrology, shares many of the traits of Mars-Nergal. Shamash of Sippar also illustrates these two phases. Like Ninib, he is a “warrior,” and often shows himself enraged against his subjects.

“The most; significant feature, however, of the sun-cult in Babylonia, which applies more particularly to Shamash of Sippar, is the association of justice and righteousness with the god. Shamash, as the judge of mankind, is he who brings hidden crimes to light, punishing the wrongdoers and righting those who have been unjustly condemned. It is he who pronounces the judgments in the courts of justice. The priests in their capacity of judges speak in his name. Laws are promulgated as the decrees of Shamash; it is significant that even so ardent a worshipper of Marduk as Hammurabi places the figure of Shamash at the head of the monument on which he inscribes the regulations of the famous code compiled by him, thereby designating Shamash as the source and inspiration of law and justice.

“The hymns to Shamash, almost without exception, voice this ascription. He is thus addressed:

“The progeny of those who deal unjustly will not prosper.

What their mouth utters in thy presence

Thou wilt destroy, what issues from their mouth thou wilt dissipate.

Thou knowest their transgressions, the plan of the wicked thou rejectest.

All, whoever they be, are in thy care;

Thou directest their suit, those imprisoned thou dost release;

Thou hearest, O Shamash, petition, prayer, and imploration.”

Another passage of the hymn declares that

“He who takes no bribe, who cares for the oppressed

Is favoured by Shamash,—his life shall be prolonged.

Turning to the Storm God in Times of Drought

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: In southern Turkey’s Amuq Valley, a curious one-inch-tall lead figurine unearthed at a rural Bronze Age site is giving archaeologists a glimpse of how villagers living around 2000 B.C. responded to a period marked by increasing drought. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2023]

A team led by Mustafa Kemal University archaeologist Murat Akar discovered the figurine while excavating a grain silo at the site, which is known as Toprakhisar Höyük. The archaeologists were instantly struck by the object’s odd appearance. Taking the form of a bull, it resembles lead trinkets that were circulated by traders in Anatolia at that time. But it also bears a likeness to larger artifacts from Mesopotamia called foundation pegs, conical or nail-shaped objects inscribed with dedications to the gods and placed under the walls of important buildings.

Akar thinks the hybrid Anatolian-Mesopotamian figurine was made by newcomers who were drawn to Toprakhisar Höyük by the area’s resilient river system, which would have made it a haven during dry periods. “We believe that the Amuq Valley was a refugee zone at the beginning of the second millennium B.C.,” he says. “Beliefs, ideas, customs, and new cult and ritual habits were likely transmitted to the region through these population movements from northern Mesopotamia.” Bulls came to be closely associated with the area’s various storm god cults, which rose to prominence around the time the object was placed in the grain silo. Perhaps it was left there by people who sought the storm god’s protection from further hardship while they built a new life in a foreign land.

Mesopotamian Demons

Ira Spar of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Demons were viewed as being either good or evil. Evil demons were thought to be agents of the gods sent to carry out divine orders, often as punishment for sins. They could attack at any moment by bringing disease, destitution, or death. Lamastu-demons were associated with the death of newborn babies; gala-demons could enter one's dreams. Demons could include the angry ghosts of the dead or spirits associated with storms. [Source: Spar, Ira. Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Some gods played a beneficent role to protect against demonic scourges. A deity depicted with the body of a lion and the head and arms of a bearded man was thought to ward off the attacks of lion-demons. Pazuzu, a demonic-looking god with a canine face and scaly body, possessing talons and wings, could bring evil, but could also act as a protector against evil winds or attacks by lamastu-demons. Rituals and magic were used to ward off both present and future demonic attacks and counter misfortune. Demons were also represented as hybrid human-animal creatures, some with birdlike characteristics. \^/

“Although the gods were said to be immortal, some slain in divine combat had to reside in the underworld along with demons. The "Land of No Return" was to be found beneath the earth and under the abzu, the freshwater ocean. There the spirits of the dead (gidim) dwelt in complete darkness with nothing to eat but dust and no water to drink.This underworld was ruled by Eresh-kigal, its queen, and her husband Nergal, together with their household of laborers and administrators. \^/

See Separate Article: MESOPOTAMIAN DEMONS africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024