Home | Category: Education, Transportation and Health

HEALTH IN MESOPOTAMIA

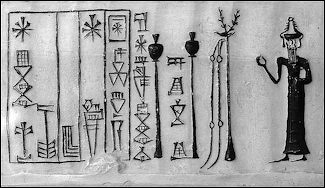

Amulet to ward off plague Anthropologist J. Lawrence Angel discovered that 30,000 years ago men averaged 5 feet 11 and women averaged 5 foot 6. In Greco-Roman times men were 5 foot 6 and women were 5 foot 0. In 1960, American men were 5 foot 9. Angel also estimated that on average men lived to be 33.3 years old and women 28.7 years old during paleolithic times and that men had lost an average of 2.2 teeth when died: 3.5 teeth in 6,500 B.C.; 6.6 missing in Roman times.

Analysis of excavated Assyrian skeletons revealed signs of sinus infections, poor nutrition and good nutrition, high fevers and thickness of the skull associated with meningitis. The "eye for an eye" phrase came from a list of penalties for surgeons on the Code of Hammurabi. If a surgeon caused someone to lose an eye through negligence the surgeon could lose his eyes.

To a large extent the treatment of illnesses believed to be be caused by evil demons was the task of the ašipu (priests) , who thus overlaps in function with the physician or asu, who worked mainly with medicaments of various kinds. It is often difficult to distinguish between his handbooks and those of the ašipu. [Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica]

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“An Ancient Mesopotamian Herbal” by Barbara Boeck, Shahina A. Ghazanfar, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

“Illness and Health Care in the Ancient Near East: The Role of the Temple in Greece, Mesopotamia, and Israel” (Harvard Semitic Monographs) by Hector Avalos (1995)

“Gastrointestinal Disease and Its Treatment in Ancient Mesopotamia: The Nineveh Treatise” by J. Cale Johnson and Krisztián Simkó (2022) Amazon.com;

Amazon.com;

“Temples of Enterprise: Creating Economic Order in the Bronze Age Near East”

by Michael Hudson (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Healing Goddess Gula: Towards an Understanding of Ancient Babylonian Medicine” by Barbara Böck (2013) Amazon.com;

“Science and Secrets of Early Medicine: Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, China, Mexico, Peru”

By Jurgen Thorwald (1963) Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Medicine: Mesopotamia’s Akkadian Queen Puabi Seated with Attendants (C. 2600 BC) Was the First Woman-Surgeon” Novel by Andrew S. Olearchyk and Renata M. Olearchyk (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Babylonian Medicine: Theory and Practice” by Markham J. Geller (2015) Amazon.com;

“Epilepsy in Babylonia” by Marten Stol (1993) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“Health and Disease in the Neolithic Lengyel Culture” by Václav Smrcka, Olivér Gábor Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Disease” by Charlotte Roberts, Keith Manchester Amazon.com;

“Ancient Medicine” (Sciences of Antiquity) by Vivian Nutton (2012) Amazon.com;

“Mummies, Disease and Ancient Cultures” by Thomas Aidan Cockburn, Eve Cockburn (1998) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Medicine” by John F. Nunn (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Papyrus Ebers: Ancient Egyptian Medicine” by Cyril P. Bryan (Translator) 2021) Amazon.com;

Beliefs About Disease in Mesopotamia

Illness had traditionally been thought of as punishment from the gods. Even so Sumerian cuneiform tablets relate that Mesopotamians had some awareness of deadly pathogens in 1770 B.C. Excavation of Assyrian tombs belonging to the elite, perhaps kings and queens, revealed that the people had few cavities but suffered from dental abscesses. Many ancient people believed that tooth pain was caused by creatures called toothworms. Describing one such worm a Babylonian poet wrote:

” The earth had created the rivers...

The marsh had created the worm

The worm went weeping...

Lift me up among the teeth

And the gums cause me to dwell!

The blood of the tooth I will suck.

And the gums will I gnaw the roots!”

Nancy Demand of Indiana University wrote: “Mesopotamian diseases are often blamed on pre-existing spirits: gods, ghosts, etc. However, each spirit was held responsible for only one of what we would call a disease in any one part of the body. So usually "Hand of God X" of the stomach corresponds to what we call a disease of the stomach. A number of diseases simply were identified by names, "bennu" for example. Also, it was recognized that various organs could simply malfunction, causing illness. [Source: The Asclepion, Prof.Nancy Demand, Indiana University - Bloomington]

Gods could also be blamed at a higher level for causing named diseases or malfunctioning of organs, although in some cases this was a way of saying that symptom X was not independent as usual, but was caused in this case by disease Y. It can also be shown that the plants used in treatment were generally used to treat the symptoms of the disease, and were not the sorts of things generally given for magical purposes to such a spirit. Presumably specific offerings were made to a particular god or ghost when it was considered to be a causative factor, but these offerings are not indicated in the medical texts, and must have been found in other texts.

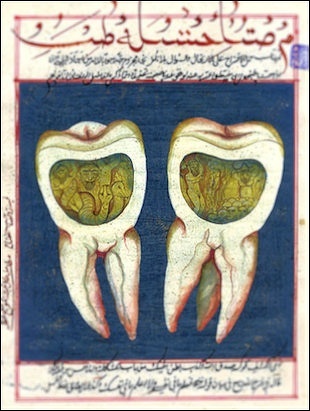

Legend of the Worm

18th century Ottoman deiction of tooth worms

In the "Legend of the Worm" the worm was vampire-like and absorbed the blood of victims, but specialized in gums. According to the Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology: The legend relates that the worm came into existence as follows: Anu created the heavens, the heavens created the earth, the earth created the rivers, and the rivers created the canals, then the canals created marshes, and the marshes created the worm. In due time the worm appeared before Shamash, the sun god, and Ea, god of the deep, weeping and hungry. "What will you give me to eat and drink?" it cried. The gods promised that it would get dried bones and scented wood. [Source: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, Encyclopedia.com]

The worm realized that this was the food of death, and answered: "What are dry bones to me? Set me upon the gums that I may drink the blood of the teeth and take away the strength of the gums." When the worm heard this legend repeated, it came under the magician's power and was dismissed to the marshes, while Ea was invoked to smite it. Different demons were exorcised by different processes. A fever patient might receive the following treatment:

Sprinkle this man with water,

Bring unto him a censer and a torch,

That the plague demon which resteth in the body of the man,

Like water may trickle away.

Demons might also be attacked by a form of image magic. The magician began by fashioning a figure of dough, wax, clay, or pitch. This figure might be placed on a fire, mutilated, or placed in running water to be washed away. As the figure suffered, so did the demon it represented, by the magic of the word of Ea.

Letters by Ancient Mesopotamian with Health Problems

Bau-gamilat, the handmaid of the king, is constantly ill; she cannot eat a morsel of food; let the king send orders that some physician may go and see her.” In another letter the writer expresses his gratitude to the King for his kindness in sending him his own doctor, who had cured him of a serious disease. “May Ishtar of Erech,” he says, “and Nana (of Bit-Ana) grant long life to the king my lord, for he sent Basa the physician of the king my lord to save my life and he has cured me; therefore may the great gods of heaven and earth be gracious to the king my lord, and may they establish the throne of the king my lord in heaven for ever; since I was dead, and the king has restored me to life.” [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

In fact there are a good many letters which relate to medical matters. Thus Dr. Johnston gives the following translation of a letter from a certain Arad-Nana, who seems to have been a consulting physician, to Esar-haddon about a friend of the prince who had suffered from violent bleeding of the nose: “As regards the patient who has a bleeding from the nose, the Rab-Mag (or chief physician) reports: ‘Yesterday, toward evening, there was a good deal of hæmorrhage.’ The dressings have not been properly applied. They have been placed outside the nostrils, oppressing the breathing and coming off when there is hæmorrhage. Let them be put inside the nostrils and then the air will be excluded and the hæmorrhage stopped. If it is agreeable to my lord the king I will go to-morrow and give instructions; (meanwhile) let me know how the patient is.”

Another letter from AradNana translated by the same Assyriologist is as follows: “To the king my lord, thy servant Arad-Nana: May there be peace for ever and ever to the king my lord. May Ninip and Gula grant health of soul and body to the king my lord. All is going on well with the poor fellow whose eyes are diseased. I had applied a dressing covering the face. Yesterday, toward evening, undoing the bandage which held it (in place), I removed the dressing. There was pus upon the dressing, the size of the tip of the little finger. If any of your gods set his hand thereto, let him say so. Salutation for ever! Let the heart of the king my lord be rejoiced. Within seven or eight days the patient will recover.”

Mesopotamian Medicines

The Sumerians are considered the originators of medication. They used medicines as early as 3,500 B.C. and developed enemas, suppositories, lotions, pills, inhalations, ointments, snuffs, poultices, and infusions.

The world oldest known prescriptions, cuneiform tablets dating back to 2000 B.C. from Nippur, Sumer, described how to make poultices, salves and washes. The ingredients, which included mustard, fig, myrrh, bat dropping, turtle shell powder, river silt, snakeskins and "hair from the stomach of a cow," were dissolved into wine, milk and beer.

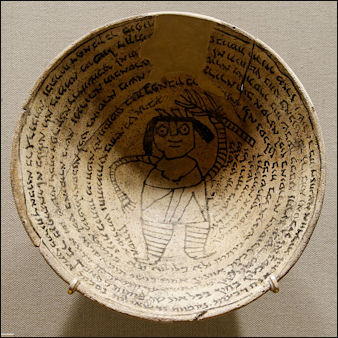

Incantation bowl

with demon, Nippur Cuneiform tablets suggest Mesopotamians used salt water for gargling, sour wine as a disinfectant, potassium nitrate obtained from urine as an astringent, and willow bark (source of aspirin) to relieve fever.

By trial and error, the Sumerians discovered that alkaline substances neutralize the stomach's natural acids and reduce the production of pepsin, which irritates the stomach's lining. The chief ingredient in their stomach relief medicines was sodium bicarbonate (baking soda).

The earliest known laxatives, used in Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, were made from ground senna pods and yellowish castor oil around 2500 B.C. The Assyrians were particularly adept laxative makers. They developed "bulk-forming" laxatives made from bran and "saline" laxatives with sodium and "stimulant" laxatives that acted on the intestinal walls to produce defecation.

“Astral Magic in Babylonia” (1995) by Erica Reiner traces the roots of Greek medicine and science to Babylonian magical practices using plants and other ingredients and seeking to harness the powers of celestial bodies.

Herodotus wrote in 430 B.C.:“The following custom seems to me the wisest of their institutions next to the one lately praised. They have no physicians, but when a man is ill, they lay him in the public square, and the passers-by come up to him, and if they have ever had his disease themselves or have known any one who has suffered from it, they give him advice, recommending him to do whatever they found good in their own case, or in the case known to them; and no one is allowed to pass the sick man in silence without asking him what his ailment is. I.198: They bury their dead in honey, and have funeral lamentations like the Egyptians. When a Babylonian has consorted with his wife, he sits down before a censer of burning incense, and the woman sits opposite to him. At dawn of day they wash; for till they are washed they will not touch any of their common vessels. This practice is observed also by the Arabians.” [Source: Herodotus, “The History”, translated by George Rawlinson, (New York: Dutton & Co., 1862]

See Separate Article: MEDICINE IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Health Care in Mesopotamia

Nancy Demand of Indiana University wrote: By examining the surviving medical tablets it is clear that there were two distinct types of professional medical practitioners in ancient Mesopotamia. The first type of practitioner was the ashipu, in older accounts of Mesopotamian medicine often called a "sorcerer." One of the most important roles of the ashipu was to diagnose the ailment. In the case of internal diseases, this most often meant that the ashipu determined which god or demon was causing the illness. The ashipu also attempted to determine if the disease was the result of some error or sin on the part of the patient. The phrase, "the Hand of..." was used to indicate the divine entity responsible for the ailment in question, who could then be propitiated by the patient. The ashipu could also attempt to cure the patient by means of charms and spells that were designed to entice away or drive out the spirit causing the disease.The ashipu could also refer the patient to a different type of healer called an asu. [Source: The Asclepion, Prof.Nancy Demand, Indiana University - Bloomington +++]

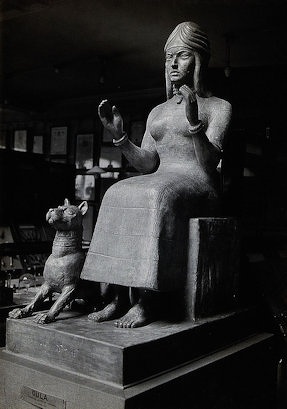

fragment of a talisman used to exorcise the sick

“Beyond the role of the ashipu and the asu, there were other means of procuring health care in ancient Mesopotamia. One of these alternative sources was the Temple of Gula. Gula, often envisioned in canine form, was one of the more significant gods of healing. While excavations of temples dedicated to Gula have not revealed signs that patients were housed at the temple while they were treated (as was the case with the later temples of Asclepius in Greece), these temples may have been sites for the diagnosis of illness. In his book Illness and Health Care in the Ancient Near East: the Role of the Temple in Greece, Mesopotamia, and Israel, Hector Avalos states that not only were the temples of Gula sites for the diagnosis of illness (Gula was consulted as to which god was responsible for a given illness), but that these temples were also libraries that held many useful medical texts. +++

“The primary center for health care was the home, as it was when the ashipu or asu were employed. The majority of health care was provided at the patient's own house, with the family acting as care givers in whatever capacity their lay knowledge afforded them. Outside of the home, other important sites for religious healing were nearby rivers. The Mesopotamian believed that the rivers had the power to care away evil substances and forces that were causing the illness. Sometimes a small hut was set up for the afflicted person either near the home or the river to aid in the families centralization of home health care.” +++

Ancient Mesopotamian Physicians

The physician is mentioned at a very early date. Thus we hear of “Ilu- bani, the physician of Gudea,” the High-priest of Lagas (2700 B.C.), and a treatise on medicine, of which fragments exist in the British Museum, was compiled long before the days of Abraham. It continued to be regarded as a standard work on the subject even in the time of the second Assyrian empire, though its prescriptions are mixed up with charms and incantations. But an attempt was made in it to classify and describe various diseases, and to enumerate the remedies that had been proposed for them. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Nancy Demand of Indiana University wrote: The asu “was a specialist in herbal remedies, and in older treatments of Mesopotamian medicine was frequently called "physician" because he dealt in what were often classifiable as empirical applications of medication. For example, when treating wounds the asu generally relied on three fundamental techniques: washing, bandaging, and making plasters. All three of these techniques of the asu appear in the world's oldest known medical document (c. 2100 B.C.). [Source: The Asclepion, Prof.Nancy Demand, Indiana University - Bloomington +++]

“The knowledge of the asu in making plasters is of particular interest. Many of the ancient plasters (a mixture of medicinal ingredients applied to a wound often held on by a bandage) seem to have had some helpful benefits. For instance, some of the more complicated plasters called for the heating of plant resin or animal fat with alkali. This particular mixture when heated yields soap which would have helped to ward off bacterial infection. +++

“While the relationship between the ashipu and the asu is not entirely clear, the two kinds of healers seemed to have worked together in order to obtain cures. The wealthiest patients probably sought medical attention from both an ashipu and an asu in order to cure an illness. It seems that the ashipu and the asu often worked in cooperation with each other in order to treat certain ailments. Beyond sharing patients, there seems to have been some overlap between the skills of the two types of healers: an asu might occasionally cast a spell and an ashipu might prescribe drugs. Evidence for this crossing of supposed occupational lines has been found in the library of an ashipu that contained pharmaceutical recipes.” +++

Hammurabi's Code of Laws 215-227: Physicians, Barbers and Vets

The Babylonian king Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.) is credited with producing the Code of Hammurabi, the oldest surviving set of laws. Recognized for putting eye for an eye justice into writing and remarkable for its depth and judiciousness, it consists of 282 case laws with legal procedures and penalties. Many of the laws had been around before the code was etched in the eight-foot-highin black diorite stone that bears them. Hammurabi codified them into a fixed and standardized set of laws. [Source: Translated by L. W. King]

Gula, the Sumerian god of healing

215) If a physician make a large incision with an operating knife and cure it, or if he open a tumor (over the eye) with an operating knife, and saves the eye, he shall receive ten shekels in money. [Source: Translated by L. W. King]

216) If the patient be a freed man, he receives five shekels.

217) If he be the slave of some one, his owner shall give the physician two shekels.

218) If a physician make a large incision with the operating knife, and kill him, or open a tumor with the operating knife, and cut out the eye, his hands shall be cut off.

219) If a physician make a large incision in the slave of a freed man, and kill him, he shall replace the slave with another slave.

220) If he had opened a tumor with the operating knife, and put out his eye, he shall pay half his value.

221) If a physician heal the broken bone or diseased soft part of a man, the patient shall pay the physician five shekels in money.

222) If he were a freed man he shall pay three shekels.

223) If he were a slave his owner shall pay the physician two shekels.

224) If a veterinary surgeon perform a serious operation on an ass or an ox, and cure it, the owner shall pay the surgeon one-sixth of a shekel as a fee.

225) If he perform a serious operation on an ass or ox, and kill it, he shall pay the owner one-fourth of its value.

226) If a barber, without the knowledge of his master, cut the sign of a slave on a slave not to be sold, the hands of this barber shall be cut off.

227) If any one deceive a barber, and have him mark a slave not for sale with the sign of a slave, he shall be put to death, and buried in his house. The barber shall swear: "I did not mark him wittingly," and shall be guiltless.

Surgery in Mesopotamia

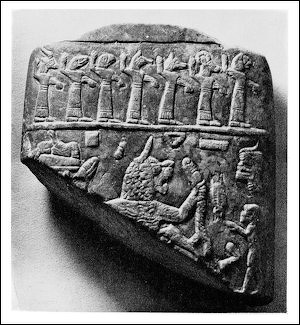

entwined snakes of Mesopotamia

Nancy Demand of Indiana University wrote: “Among Hammurabi's laws were several that pertained to the liability of physicians who performed surgery. These laws state that a doctor was to be held responsible for surgical errors and failures. Since the laws only mention liability in connection with "the use of a knife," it can be assumed that doctors in Hammurabi's kingdom were not liable for any non-surgical mistakes or failed attempts to cure an ailment. [Source: The Asclepion, Prof.Nancy Demand, Indiana University - Bloomington +++]

“It is also interesting to note that according to these laws, both the successful surgeon's compensation and the failed surgeon's liability were determined by the status of his patient. Therefore, if a surgeon operated and saved the life of a person of high status, the patient was to pay ten shekels of silver. If the surgeon saved the life of a slave, he only received two shekels. However, if a person of high status died as a result of surgery, the surgeon risked having his hand cut off. While if a slave died from receiving surgical treatment, the surgeon only had to pay to replace the slave. This use of status to evaluate misdeeds does not seem to appear in other, similar "codes" however. +++

“Regardless of the risks associated with performing surgery, at least four clay tablets have survived that describe a specific surgical procedure. Unfortunately, one of the four tablets is too fragmentary to be deciphered. Of the remaining three, one seems to describe a procedure in which the asu cuts into the chest of the patient in order to drain pus from the pleura. The other two surgical texts belong to the collection of tablets entitled "Prescriptions for Diseases of the Head." One of these texts mentions the knife of the asu scraping the skull of the patient. The final surgical tablet mentions the postoperative care of a surgical wound. This tablet recommends the application of a dressing consisting mainly of sesame oil, which acted as an anti-bacterial agent. +++

See Separate Article: SURGERY AND DENTISTRY IN ANTIQUITY AND VERY ANCIENT TIMES factsanddetails.com

Sumerian Eye Makeup, Conjunctivitis and the 'Evil Eye'

physicians cylinder seal impression from ur-lugal-Edinna

John Alan Halloran wrote in sumerian.org: “The Sumerian language has preserved a record of their battles against conjunctivitis, also known as 'pink eye', an eye condition which the Sumerians called igi-hulu, 'evil eye'. Conjunctivitis is an inflammation of the mucous membrane that covers the eyeball, which can be brought on by bacteria, viruses, or inadvertent soap in the eye. You can read about this potentially dangerous condition here: [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org January 27, 2014 ***]

“There is a Sumerian expression that indicates that this condition had already become a subject of fear and superstition in Sumerian times — igi-hul...dim2: to put the evil eye (on someone) ('eyes/face' + 'evil' + 'to fashion'). In most traditional cultures there is an extreme fear of the 'Evil Eye'. They recite incantations, give signs, and will do everything possible to avoid its fateful curse. ***

“The Sumerians were like many other peoples in having traditions about the medicinal use of different plants and herbs, some of which have antiseptic properties. These traditions are preserved in the vocabulary of their language. When Logogram Publishing publishes the English-Sumerian index to my Sumerian Lexicon (2006) book, it will be easier for researchers to look up what are these plants and herbs. But the Sumerian natural remedies were largely the same as are used today among the inhabitants of Iraq and Arabia. ***

“The Sumerian vocabulary confirms that the practice of eye makeup originated for eye protection, not for cosmetic reasons. It also shows that the practice of applying protective eye makeup was not limited to the ancient Egyptians. Here are two entries from my Sumerian Lexicon (2006) book: 1) šembi, šimbi: kohl, i.e., a cosmetic, mascara, or eye-protection paste originally made from charred frankincense resin and later from powdered antimony (stibium) or lead compounds (cf., šem-bi-zi-da, 'kohl'; šim, 'perfumed resin'; šim-gig, 'frankincense'; im-sig7-sig7, 'antimony paste'). 2) šem-bi-zi-da: kohl; a paste originally made from charred frankincense resin and later from powdered antimony (stibium) or lead compounds; a darkening eye cosmetic with antibacterial properties - used as a protection against eye disease as well as giving relief from the glare of the sun ('kohl' + 'good; true' + nominative; Akk., guhlu, 'kohl' - cf., igi-hulu, 'evil-eye'). ***

“The etymology shows that Akkadian guhlu is a loanword from Sumerian, where it evolved through vowel harmony from the Sumerian term for 'evil-eye' into our word 'kohl'. Furthermore, according to Stephan Guth, Professor of Arabic at the University of Oslo, our word 'alcohol' "is derived from the Arabic al-kuhl, which means 'kohl'. When the Europeans became familiar with this substance in Andalusia, which was also used for medical purposes, they referred to it and gradually all other fine powders, and subsequently all kinds of volatile essences, as alcohol." So the etymology of 'alcohol' can now be traced through a circuitous path all the way back to ancient Sumerian igi-hulu, 'evil-eye'. ***

“Frankincense resin has such strong antibiotic properties that the ancient Egyptians used its oil to clean the body and organs during mummification, helping to prevent putrefaction. A Google search for "charred frankincense" returns almost a thousand results. Frankincense, however, was rare and expensive, having to be imported from Arabia, which explains why the Sumerians learned to substitute powdered antimony or lead compounds for it in their eye makeup.” ***

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024