Home | Category: Education, Transportation and Health

ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN MEDICINES

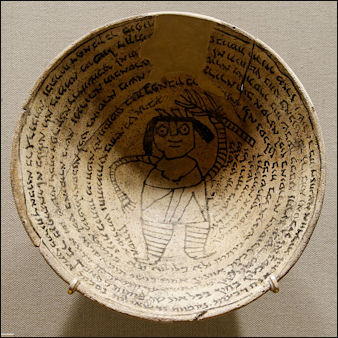

Incantation bowl

with demon, Nippur The Sumerians are considered the originators of medication. They used medicines as early as 3,500 B.C. and developed enemas, suppositories, lotions, pills, inhalations, ointments, snuffs, poultices, and infusions.

By trial and error, the Sumerians discovered that alkaline substances neutralize the stomach's natural acids and reduce the production of pepsin, which irritates the stomach's lining. The chief ingredient in their stomach relief medicines was sodium bicarbonate (baking soda).

The earliest known laxatives, used in Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, were made from ground senna pods and yellowish castor oil around 2500 B.C. The Assyrians were particularly adept laxative makers. They developed "bulk-forming" laxatives made from bran and "saline" laxatives with sodium and "stimulant" laxatives that acted on the intestinal walls to produce defecation.

“Astral Magic in Babylonia” (1995) by Erica Reiner traces the roots of Greek medicine and science to Babylonian magical practices using plants and other ingredients and seeking to harness the powers of celestial bodies.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Astral Magic in Babylonia” by Erica Reiner (1995) Amazon.com;

“An Ancient Mesopotamian Herbal” by Barbara Boeck, Shahina A. Ghazanfar, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

“Illness and Health Care in the Ancient Near East: The Role of the Temple in Greece, Mesopotamia, and Israel” (Harvard Semitic Monographs) by Hector Avalos (1995)

“Gastrointestinal Disease and Its Treatment in Ancient Mesopotamia: The Nineveh Treatise” by J. Cale Johnson and Krisztián Simkó (2022) Amazon.com;

Amazon.com;

“Temples of Enterprise: Creating Economic Order in the Bronze Age Near East”

by Michael Hudson (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Healing Goddess Gula: Towards an Understanding of Ancient Babylonian Medicine” by Barbara Böck (2013) Amazon.com;

“Science and Secrets of Early Medicine: Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, China, Mexico, Peru”

By Jurgen Thorwald (1963) Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Medicine: Mesopotamia’s Akkadian Queen Puabi Seated with Attendants (C. 2600 BC) Was the First Woman-Surgeon” Novel by Andrew S. Olearchyk and Renata M. Olearchyk (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Babylonian Medicine: Theory and Practice” by Markham J. Geller (2015) Amazon.com;

“Epilepsy in Babylonia” by Marten Stol (1993) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“Health and Disease in the Neolithic Lengyel Culture” by Václav Smrcka, Olivér Gábor Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Disease” by Charlotte Roberts, Keith Manchester Amazon.com;

“Ancient Medicine” (Sciences of Antiquity) by Vivian Nutton (2012) Amazon.com;

“Mummies, Disease and Ancient Cultures” by Thomas Aidan Cockburn, Eve Cockburn (1998) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Medicine” by John F. Nunn (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Papyrus Ebers: Ancient Egyptian Medicine” by Cyril P. Bryan (Translator) 2021) Amazon.com;

Some Ancient Mesopotamian Cures

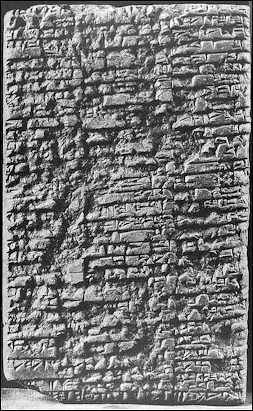

The world oldest known prescriptions, cuneiform tablets dating back to 2000 B.C. from Nippur, Sumer, described how to make poultices, salves and washes. The ingredients, which included mustard, fig, myrrh, bat dropping, turtle shell powder, river silt, snakeskins and "hair from the stomach of a cow," were dissolved into wine, milk and beer.

Cuneiform tablets suggest Mesopotamians used salt water for gargling, sour wine as a disinfectant, potassium nitrate obtained from urine as an astringent, and willow bark (source of aspirin) to relieve fever.

Herodotus wrote in 430 B.C.:“The following custom seems to me the wisest of their institutions next to the one lately praised. They have no physicians, but when a man is ill, they lay him in the public square, and the passers-by come up to him, and if they have ever had his disease themselves or have known any one who has suffered from it, they give him advice, recommending him to do whatever they found good in their own case, or in the case known to them; and no one is allowed to pass the sick man in silence without asking him what his ailment is. I.198: They bury their dead in honey, and have funeral lamentations like the Egyptians. When a Babylonian has consorted with his wife, he sits down before a censer of burning incense, and the woman sits opposite to him. At dawn of day they wash; for till they are washed they will not touch any of their common vessels. This practice is observed also by the Arabians.” [Source: Herodotus, “The History”, translated by George Rawlinson, (New York: Dutton & Co., 1862]

The remedies are often a compound of the most heterogeneous drugs, some of which are of a very unsavory nature. However, the patient, or his doctor, is generally given a choice of the remedies he might adopt. Thus for an attack of spleen he was told either to “slice the seed of a reed and dates in palm-wine,” or to “mix calves' milk and bitters in palm-wine,” or to “drink garlic and bitters in palm-wine.” “For an aching tooth,” it is laid down, “the plant of human destiny (perhaps the mandrake) is the remedy; it must be placed upon the tooth.[Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The fruit of the yellow snakewort is another remedy for an aching tooth; it must be placed upon the tooth.… The roots of a thorn which does not see the sun when growing is another remedy for an aching tooth; it must be placed upon the tooth.” Unfortunately it is still impossible to assign a precise signification to most of the drugs that are named, or to identify the various herbs contained in the Babylonian pharmacopoeia. As time passed on, the charms and other superstitious practices which had at first played so large a part in Babylonian medicine fell into the background and were abandoned to the more uneducated classes of society. The conquest of Western Asia by the Egyptian Pharaohs of the eighteenth dynasty brought Babylonia into contact with Egypt, where the art of medicine was already far advanced.

Difficulty Working Out the Ingredients of Mesopotamian Medicine

Pharmacopoeia from Nippur, 225 BC

Nancy Demand of Indiana University wrote: ““ Another important consideration for the study of ancient Mesopotamian medicine is the identification of the various drugs mentioned in the tablets. Unfortunately, many of these drugs are difficult or impossible to identify with any degree of certainty. Often the asu used metaphorical names for common drugs, such as "lion's fat" (much as we use the terms "tiger lilly" or "baby's breath"). [Source: The Asclepion, Prof.Nancy Demand, Indiana University - Bloomington +++]

Of the drugs that have been identified, most were plant extracts, resins, or spices. Many of the plants incorporated into the asu medicinal repertoire had antibiotic properties, while several resins and many spices have some antiseptic value, and would mask the smell of a malodorous wound. Beyond these benefits, it is important to keep in mind that both the pharmaceuticals and the actions of the ancient physicians must have carried a strong placebo effect. Patients undoubtedly believed that the doctors were capable of healing them. Therefore, at the very least, visiting the doctor psychologically reinforced the notion of health and wellness."

“Whether or not ancient Mesopotamian medicine passed on a legacy that ultimately influenced the doctors of subsequent civilizations is a question that will never be complete answered. While many of the basic tenants of medicine, such as bandaging and the collection of medical texts, began in Mesopotamia, other cultures may have developed these practices independently. Even in Mesopotamia itself, many of the ancient techniques became extinct after surviving for thousands of years. It was Egyptian medicine that seems to have had the most influence on the later development of medicine, through the medium of the Greeks.” [Source: The Asclepion, Prof.Nancy Demand, Indiana University - Bloomington]

Sources on Mesopotamian Medicine

Nancy Demand of Indiana University wrote: “Most of the information available to modern scholars comes from cuneiform tablets. There are no useful pictorial representations that have survived in ancient Mesopotamian art, nor has a significant amount of skeletal material yet been analyzed. Unfortunately, while an abundance of cuneiform tablets have survived from ancient Mesopotamia, relatively few are concerned with medical issues. Many of the tablets that do mention medical practices have survived from the library of Asshurbanipal, the last great king of Assyria. The library of Asshurbanipal was housed in the king's palace at Nineveh, and when the palace was burned by invaders, around 20,000 clay tablets were baked (and thereby preserved) by the great fire. [Source: The Asclepion, Prof.Nancy Demand, Indiana University - Bloomington +++]

We have indeed evidence that the medical system and practice of Egypt had been introduced into Asia. When the great Egyptian treatise on medicine, known as the Papyrus Ebers, was written in the sixteenth century B.C., one of the most fashionable oculists of the day was a “Syrian” of Gebal, and as the study of the disease of the eye was peculiarly Egyptian, we must assume that his science had been derived from the valley of the Nile. It must not be supposed, however, that the superstitious beliefs and practices of the past were altogether abandoned, even by the most distinguished practitioners, any more than they were by the physicians of Europe in the early part of the last century.[Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

“In the early 1920's, the 660 medical tablets from the library of Asshurbanipal were published by Cambell Thompson. Other medical texts have been published more recently. For example, Franz Kocher has published a series of volumes called Die Babylonishch-Assyrische Medizin. The first four of these contain 420 tablets found from sites other than Assurbanipal's library, including the library of a medical practitioner (an asipu) from Neo-Assyrian Assur, as well as Middle Assyrian and Middle Babylonian texts. +++

“The remaining two volumes of Kocher's work augment Campbell Thompson, providing new joins of broken fragments and much material uncovered in the British Museum. At least one more volume of Nineveh texts has been announced. In addition, the series Spaet Babylonische Texte aus Uruk contains some 30 medical texts not included in Kocher's work. The vast majority of these tablets are prescriptions, but there are a few series of tablets that contained entries that were directly related to one another, and these have been labeled "treatises." +++”

“Modern Sources: Hector Avalos, Illness and Health Care in the Ancient Near East: the Role of the Temple in Greece, Mesopotamia, and Israel; M.Stol, Epilepsy in Babylonia (1993) JoAnn Scurlock, "Witchcraft and Magic in the Ancient Nar East and the Bible," in Encyclopedia of Women and World Religion; JoAnn Scurlock, "Physician, Exorcist, Conjurer, Magician: A Tale of Two Healing Professionals," Papers of the 1995 Mesopotamian Magic Conference. Mary Coleman and JoAnn Scurlock, "Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers in Ancient Mesopotamia," Journal of Tropical Medicine (forthcoming); Journal des Médecines Cunéiformes http://www.oriental.cam.ac.uk/jmc

"Treatise of Medical Diagnosis and Prognoses”

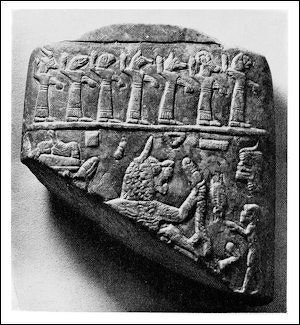

fragment of a talisman used to exorcise the sick

Nancy Demand of Indiana University wrote: “The largest surviving such medical treatise from ancient Mesopotamia is known as "Treatise of Medical Diagnosis and Prognoses." The text of this treatise consists of 40 tablets collected and studied by the French scholar R. Labat. Although the oldest surviving copy of this treatise dates to around 1600 B.C., the information contained in the text is an amalgamation of several centuries of Mesopotamian medical knowledge. [Source: The Asclepion, Prof.Nancy Demand, Indiana University - Bloomington +++]

“The diagnostic treatise is organized in head to toe order with separate subsections covering convulsive disorders, gynecology and pediatrics. It is unfortunate that the antiquated translations available at present to the non-specialist make ancient Mesopotamian medical texts sound like excerpts from a sorceror's handbook. In fact, as recent research is showing, the descriptions of diseases contained in the diagnostic treatise demonstrate a keen ability to observe and are usually astute. +++

“Virtually all expected diseases can be found described in parts of the diagnostic treatise, when those parts are fully preserved, as they are for neurology, fevers, worms and flukes, VD and skin lesions. The medical texts are, moreover, essentially rational, and some of the treatments, as for example those designed for excessive bleeding (where all the plants mentioned can be easily identified), are essentially the same as modern treatments for the same condition.” +++

Nineveh Medical Encyclopaedia

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Archaeologists also found an assemblage of 50 tablets that researchers have only recently realized compose a medical reference manual. Known as the Nineveh Medical Encyclopaedia, it is the oldest systematically organized medical handbook in the world. The compendium contains information about common bodily ailments, listed from head to toe, and provides diagnostic descriptions of each affliction and instructions on how to cure it. This sometimes involves mixing different plants together to create a potion or a salve. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

For example, one method of curing a headache instructs: Crush and sieve together kukru[an aromatic], burashu [juniper], nikiptu [spurge], kammantu [plant seed], sea algae, and ballukku [an aromatic]. You boil down the mixture in beer, you shave his head, and you put it on as a bandage; then he will recover.

Other ailments require supernatural remedies conjured by reciting magical incantations and appealing to Assyrian gods for help, such as this cure for an eye injury: If a man constantly sees a flash of light, he should say three times as follows: “I belong to Enlil and Ninlil, I belong to Ishtar and Nanaya.” He says this, then he should recover.

Nancy Demand of Indiana University wrote: The asu “was a specialist in herbal remedies, and in older treatments of Mesopotamian medicine was frequently called "physician" because he dealt in what were often classifiable as empirical applications of medication. For example, when treating wounds the asu generally relied on three fundamental techniques: washing, bandaging, and making plasters. All three of these techniques of the asu appear in the world's oldest known medical document (c. 2100 B.C.). [Source: The Asclepion, Prof.Nancy Demand, Indiana University - Bloomington +++]

“The knowledge of the asu in making plasters is of particular interest. Many of the ancient plasters (a mixture of medicinal ingredients applied to a wound often held on by a bandage) seem to have had some helpful benefits. For instance, some of the more complicated plasters called for the heating of plant resin or animal fat with alkali. This particular mixture when heated yields soap which would have helped to ward off bacterial infection. +++

“While the relationship between the ashipu and the asu is not entirely clear, the two kinds of healers seemed to have worked together in order to obtain cures. The wealthiest patients probably sought medical attention from both an ashipu and an asu in order to cure an illness. It seems that the ashipu and the asu often worked in cooperation with each other in order to treat certain ailments. Beyond sharing patients, there seems to have been some overlap between the skills of the two types of healers: an asu might occasionally cast a spell and an ashipu might prescribe drugs. Evidence for this crossing of supposed occupational lines has been found in the library of an ashipu that contained pharmaceutical recipes.” +++

Magic Cures and Spiritual Treatments

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: In the ancient Near East, illness was as much a spiritual affliction as a physical one. Demons and ghosts played large roles in diagnosis and treatment, but that’s not to say that the practice of medicine wasn’t codified. One collection of cuneiform texts lists hundreds of medically active substances. And the Late Babylonian diagnostic manual called Sakikku, or “All Diseases,” reveals the careful diagnostic observation of ashipu, or doctor-scholars. The manual, which dates to around the sixth century B.C., consists of 40 tablets, including a treatise on the diagnosis of epilepsy, called miqtu, or “the falling disease.” The writer explains the subtleties of the neurological disease’s presentation in great detail, provides basic prognoses, and ascribes different kinds of seizures to particular malevolent spirits. “[If the epilepsy] demon falls upon him and on a given day he seven times pursues him — [he has been touched by the] hand of the departed spirit of a murderer. He will die.” [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

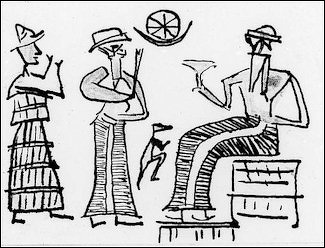

Adad, the god that causes colds

According to the Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology: In treating the sick, the magician might release a raven at the bedside of the sick person so that it would conjure the demon of fever to take flight likewise. Sacrifices could also be offered, as substitutes for patients, to provide food for the spirit of the disease. [Source: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, Encyclopedia.com]

A young goat was slain and the priest repeated:

The kid is the substitute for mankind;

He hath given the kid for his life,

He hath given the head of the kid for the head of the man.

A pig might be offered:

Give the pig in his stead

And give the flesh of it for his flesh,

The blood of it for his blood.

The cures were numerous and varied. After the patient recovered, the mashmashu priests purified the house. The ceremony entailed the sprinkling of sacred water, the burning of incense, and the repetition of magical charms. People protected their homes against attack by placing certain plants over the doorways and windows. The halter of a donkey, or ass, was apparently used, in the same manner that horseshoes have been used in Europe to repel witches and evil spirits.

Treatment by a Royal Assyrian Doctor

Priests were invoked only when the ordinary remedies had failed, and when no resource seemed left except the aid of spiritual powers. Otherwise the doctor depended upon his diagnosis of the disease and the prescriptions which had been accumulated by the experience of past generations. At the head of the profession stood the court-physician, the Rab-mugi or Rab-mag as he was called in Babylonia. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

In Assyria there was more than one doctor attached to the royal person, but letters have come down to us from which we learn that the royal physicians were at times permitted to attend private individuals when they were sick. Thus we have a letter of thanks to the Assyrian King from one of his subjects full of gratitude to the King for sending his own doctor to the writer, who had accordingly been cured of a dangerous disease. “May Ishtar of Erech,” he says, “and Nana (of Bit-Anu) grant long life to the king my lord, for he has sent Basa, the royal physician, to save my life, and he has cured me; may the great gods of heaven and earth be therefore gracious to the king my lord, and may they establish the throne of the king my lord in heaven for ever, since I was dead and the king has restored me to life.”

Another letter contains a petition that one of the royal physicians should be allowed to visit a lady who was ill. “To the king my lord,” we read, “thy servant, Saulmiti-yuballidh, sends salutation to the king my lord: may Nebo and Marduk be gracious to the king my lord for ever and ever. Baugamilat, the handmaid of the king, is constantly ill; she cannot eat a morsel of food. Let the king send orders that some physician may go and see her.” In this case, however, it is possible that the lady, who seems to have been suffering from consumption, belonged to the harîm of the monarch, and it was consequently needful to obtain the royal permission for a stranger to visit her, even though he came professionally.

Assyrian the Demon Epilepsy Tablet

Candida Moss, Daily Beast: The earliest image of the ancient demon believed to cause epilepsy has been discovered in the archives of a museum in Berlin. The 2,670-year-old tablet, which was originally part of the library of a family of exorcists, shows the demon with curvy horns, a long tail, a serpent’s tongue, and what might be a reptilian eye. Not that different, in other words, than some Christian depictions of the Devil. [Source:Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 12, 2020]

Dr. Troels Pank Arbøll, an Assyriologist at the University of Copenhagen, discovered the demon when he was examining an ancient tablet at the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin. The tablet had been examined many times before, Arbøll told LiveScience, but he “was the first one to notice the drawing.” The clay tablet, which is written in ancient cuneiform, describes a cure for convulsions, twitching and muscle movement. The Assyrians call this disease “bennu,” a condition that many modern scholars believe refers to epilepsy. It was only when Arbøll examined the tablet more closely that he noticed the faint outline of a figure on the lower half of the tablet. He published the results of his research in Le Journal des Médecines Cunéiformes.

For ancient Assyrians, seizures were a symptom not of epilepsy, but of demonic possession. In her recently published book Ancient Medicine, Dr. Laura Zucconi writes that the “falling diseases” classified as bennu in ancient literature were either connected to a malicious demon or to the moon god Sin. It’s likely that a number of other conditions, including forms of mental illness, were also lumped into this category. The connection between the moon and insanity was very common in the ancient world; the English word “lunatic” comes from the Latin for “moon.” Ancient Assyrian cures for driving out the epilepsy demon include hanging “a mouse and a shoot of a thornbush” on the patient’s door; an exorcist dressed in a red garment and cloak; a raven, and a falcon.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024