Home | Category: First Cities, Archaeology and Early Signs of Civilization / Sumerians and Akkadians

NEOLITHIC SYRIA

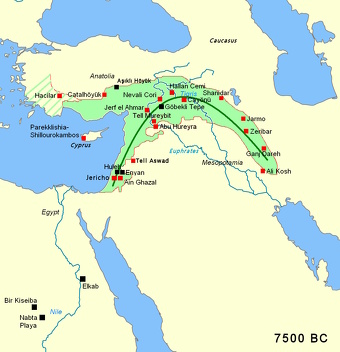

“Past studies have highlighted two main hypotheses to describe and explain the beginnings of plant domestication. In the 1990s, the belief was that domesticated plants had first appeared in Turkey, and that this was a rapid process that spread to the neighbouring regions in a short space of time.In contrast, the recent dominant theory is that cereal domestication was a protracted process that developed all over the Middle East from 11,600 to 10,700 years ago. However, it remained unclear whether domestication happened at the same time in the different countries or if there was regional diversity. ||*||

“In research, published in PNAS, researchers have tried to answer this question. They have shown that the cultivation of cereals during the Neolithic was only common in the southern-central Levant – such as in southern Syria. It took more time to arrive in other regions of the eastern Fertile Crescent – such as Iraq, Iran and southern Turkey.||*||

“The researchers started working at the archaeological Neolithic site of Tell Qarassa North in southern Syria. There, plant remains suggest that by 10,700 years ago cereals such as barley were being cultivated in important proportions. The study presents it as one of the earliest sites in the Middle East with evidence of morphologically domesticated wheat and barley. But when the scientists from the University of the Basque Country and the University of Copenhagen looked at the evidence from sites located in the eastern Fertile Crescent, they found no evidence of similar practices at this time.

RELATED ARTICLES:

NEOLITHIC TELL SITES IN SYRIA: URBANIZATION, WARFARE AND TIES TO URUK AND THE SUMERIANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

STONE AGE PALESTINE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NEOLITHIC SITES IN ISRAEL-PALESTINE: LARGE, OLD AND UNDERWATER SITES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NEOLITHIC ISRAEL-PALESTINE: CULTS, SPIRIT MASKS AND EARLY URBANIZATION africame.factsanddetails.com ;

JERICHO: HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGY, PEOPLE, PLASTERED SKULLS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NEOLITHIC JORDAN: SITES, AIN GHAZAL, STRANGE STATUES AND HUNTING KITES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NATUFIANS (12,500-9500 B.C.): SETTLEMENTS, PROTO-AGRICULTURE, ARCHAEOLOGY factsanddetails.com ;

NATUFIAN LIFE AND CULTURE (14,500-11,500 YEARS AGO) africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ORIGIN AND EARLY HISTORY OF AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Lithic Technology of Neolithic Syria” (BAR Archaeopress) by Yoshihiro Nishiaki (2000) Amazon.com;

“Tell Hamoukar, Volume 1. Urbanism and Cultural Landscapes in Northeastern Syria: The Tell Hamoukar Survey, 1999-2001" (Oriental Institute Publications) by Jason A. Ur (2011) Amazon.com;

“Excavations at Tell Brak 4: Exploring an Upper Mesopotamian Regional Centre, 1994-1996. (McDonald Institute Monographs) by Wendy Matthews (2003) Amazon.com;

“Excavations at Tell Nebi Mend, Syria: Volume by Peter J. Parr (2015) Amazon.com;

“Tell Qaramel 1999-2007: Protoneolithic and Early Pre-pottery Neolithic Settlement in Northern Syria” (English and French Edition) by Youssef Kanjou and Ryszard F. Mazurowski (2016) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Archaeology of Jordan (BAR International) by Donald O. Henry (2000) Amazon.com;

“Life in Neolithic Farming Communities: Social Organization, Identity, and Differentiation” by Ian Kuijt (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Revolution in the Near East: Transforming the Human Landscape”

by Alan H. Simmons and Dr. Ofer Bar-Yosef (2011) Amazon.com;

“Natufian Foragers in the Levant: Terminal Pleistocene Social Changes in Western Asia” by Ofer Bar-Yosef and François R. Valla (2013) Amazon.com;

“Early Urbanizations in the Levant: A Regional Narrative” by Raphael Greenberg (2002) Amazon.com;

“Jericho: Dreams, Ruins, Phantoms” by Robert Ruby (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Leopard's Tale” by Ian Hodder (2006) Amazon.com;

“Peopling the Landscape of Çatalhöyük: Reports from the 2009-2017" by Ian Hodder Amazon.com;

“Projectile Points, Hunting and Identity at Neolithic Çatalhöyük, Turkey”

by Lilian Dogiama (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World” by David W. Anthony (2010) Amazon.com;

Neolithic Pre-Pottery and Pottery Stages in Southwest Asia

In the archaeology of Southwest Asia (the Near East, Middle East) — which includes the Levant (Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon) and Anatolia (present-day Turkey) — the Middle to Late Neolithic period, also known as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period, is divided into two periods: 1) Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) and 2) Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB). The terms were originally defined by Kathleen Kenyon, an archaeologist who worked extensively at Jericho in Palestine in the 1950s. PPNA and PPNB cultures developed from the Mesolithic. Southern- Levantine-based Natufian culture. However, PPNB shows evidence of a northerly origin, possibly indicating an influx from northeastern Anatolia. [Source: Wikipedia]

Tell Hamoukar

1) The PPNA culture dates around 12,000 to 10,800 years ago (10,000–8800 B.C.) and is associated most with the southern Levant. It is characterized by tiny circular mud-brick dwellings, the early cultivation of crops, the hunting of wild game, and unique burial customs in which bodies were buried below the floors of dwellings. 2) The PPNB culture was centered in upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, and dates to around 10,800 to 8,500 years ago (8800–6500 B.C.). It differs from the PPNA period in that people relied more on domesticated animals to supplement their mixed agrarian and hunter-gatherer diet. In addition, the flint tool kit of the period is new and quite different from that of the earlier period.

Ceramic Neolithic or Pottery Neolithic, is the final part of the Neolithic period. It followed PPNB and is sometimes further divided into Pottery Neolithic A (PNA) and Pottery Neolithic B (PNB) phases. The Late Neolithic period in Southwest Asia began with the first experiments with pottery, around 7000 B.C. and lasted until the discovery of copper metallurgy and the start of the Chalcolithic (Copper Age) around 4500 B.C.

Were Cereals First Domesticated at Tell Qarrassa in Syria?

According to the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC): 11,000 years ago, a Syrian community began a practice which would change man's relationship with his surroundings forever: the initiation of cereal domestication and, with it, the commencement of agriculture, a process which lasted several millennia. The discoveries, made at the Tell Qarassa North archaeological site, situated near the city of Sweida in Syria, are the oldest evidence of the domestication of three species of cereal: one of barley and two of wheat (spelt and farrow). The team from the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and the Universities of Cantabria and the Basque Country (both in northern Spain) was led by CSIC's Juan José Ibáñez, and excavated in the area between 2009 and 2010. Scientific investigators from the Universities of Copenhagen and London also collaborated in the study which was published in magazine Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). [Source: Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) December 5, 2016]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: After the end of the last Ice Age, people settle in areas where they can exploit the local species of wheat and barley, and animals such as gazelle. Most of these settlements occur in an arc, the so-called Fertile Crescent, stretching from the southern tip of the Dead Sea north toward the Anatolian plateau, moving east to the northern Mesopotamian plains, and ending in southwestern Iran. In the eastern Mediterranean, this culture is known as Natufian and lasts more than a thousand years, from around 11,000 B.C. to about 9300 B.C., when the sites appear to be abandoned.

By 8500 B.C., permanent settlements appear in large numbers where an increasingly wider range of domesticated plants and animals offer an ever more reliable form of subsistence. As these new communities grow, more elaborate forms of architecture and artistic representation reflect an increasingly differentiated social hierarchy. In the third millennium B.C., during the Early Bronze Age, local city-states develop. These are variously linked by trade with Egypt, north Syria, and Anatolia.

Gideon Lewis-Kraus wrote in The New Yorker: About eight thousand years ago, the villagers of Tell Sabi Abyad, in present-day Syria, saw to a variety of complex tasks — pasturing the flocks; sowing, harvesting, and threshing grain; weaving flax; making beads; and carving stones — that presumably required extensive inter-household coöperation, yet everyone lived in uniform dwellings. Though writing wasn’t invented for another three thousand years, a scheme of geometric tokens, stored and archived in a central if nondescript depot, had been put in place to monitor resource administration. The archeological remains of the village, remarkably preserved by a catastrophic fire that baked its structures of mud and clay, show no signs of caste division or a presiding authority. [Source: Gideon Lewis-Kraus, The New Yorker, November 8, 2021]

Grains Domesticated in Syria Before Mesopotamia and Anatolia?

Based on plant remains found at a site in Syria it appears grains were domesticated in Syria long before they appeared in Iraq or Iran and even before they were domesticated in Anatolia (Turkey), the purported birthplace of agriculture. Léa Surugue wrote in the International Business Times: “Ancient plant remains suggest that the domestication of cereals, which led to the beginning of agriculture, appeared at different times in the Levant and in the eastern Fertile Crescent. Some countries, such as ancient-days Turkey, Iran and Iraq, saw Neolithic populations exploiting legumes, fruits and nuts long before they cultivated cereals. [Source: Léa Surugue, International Business Times, December 5, 2016 ||*||]

Although it was already known that cereal breeding took place in the Near East, it was not known whether the first domesticated cereals appeared in one region or in several regions simultaneously, or, if the first case were true, in which region. "The process began when hunter gatherer communities started collecting wild cereals, leading in turn to these wild cereals being sown, then reaped using sickles. This initial crop husbandry led to the selective breeding of cereal grains. Gradually, domestic traits became more and more dominant", explains Ibañez.

To be precise, it is this work at Tell Qarrassa which allows samples of cereals from the very first phase in the domestication process to be identified. Of all the cereals which were grown at the site, around 30 percent show domestic traits whilst the remainder continue to show traits which are characteristic of wild cereals. "We now know that the cereals from Tell Qarassa were sown in autumn and harvested in February and March, before reaching full maturity to prevent the risk- given that they were still partially wild- of heads breaking off and being lost at harvest. The crop was cut close to the ground so as to make full use of the straw and, once collected, it would be thrashed and the grain cleaned in the courtyards outside their homes before being stored inside. Prior to being eaten, the grain was crushed in a mortar and pestle then ground in hand mills", explains the CSIC investigator.

The information obtained at Tell Qarassa shows both the advanced level of technical development of these first farming communities and also that the domestication process of cereals unfolded at varying rates in the different regions of the Near East. "It has yet to be discovered whether the later appearance of domesticated cereals in these regions was due to the use of those cereals originating in the south of Syria which we have been studying, or whether other independent domestication processes took place elsewhere", concludes Ibañez.

'Wand' Engraved With Human Faces Found at Tell Qarassa

In 2014, archaeologists found an ancient 'wand' engraved with two human faces near a burial site in southern Syria. The 9,000-year-old item, probably made of an auroch rib bone, likely depicted 'powerful supernatural beings,' archaeologists said. They excavated the wand from Tell Qarassa, one the few archaeological sites not damaged by war in Syria. [Source: Haaretz, Mar 17, 2014]

Haaretz reported: The five centimeters (two inch) wand was found near a burial site, where 30 headless skeletons were discovered previously. Archaeologists say the findings shed light on the rituals of people who lived in the Neolithic period. "The find is very unusual. It's unique," study co-author Frank Braemer, an archaeologist at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in France told Livescience.

"Earlier traditions of figurative art had avoided the detailed and naturalistic representation of the human face. Fundamental changes occurred during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic with the famous plastered skulls of Jericho and other sites," International Business Times cited the archaeologists as saying. "Statues, masks and smaller carvings also appeared," they said in the findings, which were published in March in the journal Antiquity.

The auroch-bone wand, found by archaeologists during digs at Tell Qarassa in 2007 and 2009, was possibly used in a burial ritual, archaeologists believe."This small bone object from a funerary layer can be related to monumental statuary of the same period in the southern Levant and south-east Anatolia that probably depicted powerful supernatural beings," the experts said. "It may also betoken a new way of perceiving human identity and of facing the inevitability of death. By representing the deceased in visual form, the living and the dead were brought closer together."

The wand was created when the inhabitants of the region were making the transition from hunter-gatherers to farmers. According to Archaeology magazine: “The carved bone artifact has been interpreted as a kind of wand used in funerary rituals. Although there are other examples of carved bone wands, none display human faces. Only two faces remain on this example, but it is clear that the wand was deliberately broken or cut, and that, at one time, there were probably more faces on the bottom. [Source: Archaeology magazine, July-August 2014]

“It is the quality of the faces on the wand, not just their existence, that is revolutionary. According to Tell Qarassa project archaeologists, the artifact is of great significance for the study of the origins and meanings of human representation. Previously, humans were portrayed in a stylized way, but on the wand and other contemporaneous artifacts from the Neolithic Near East, faces start to be portrayed more naturalistically. The artist clearly wanted to focus attention on the closed eyes and mouth, as these are the most deeply engraved features. While no individual person is represented, there is a deliberate attempt to stress facial traits and, according to the archaeologists, concepts of personhood. This represents “a major innovation in the way the first farming communities conceived of the human image and a new way of perceiving human identity,” says archaeologist Juan José Ibañez Estevez.

See Separate Article: NEOLITHIC SKULL CULTS AND HUMAN SACRIFICES IN THE MIDDLE EAST africame.factsanddetails.com

Natufians

The Natufian culture refers to mostly hunter-gatherers who lived in modern-day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria approximately 15,000 to 11,500 years ago. Merging nomadic and settled lifestyles, they were among the first people to build permanent houses and cultivate edible plants. The advancements they achieved are believed to have been crucial to the development of agriculture during the time periods that followed them.

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica: Mainly hunters, the Natufians supplemented their diet by gathering wild grain; they likely did not cultivate it. They had sickles of flint blades set in straight bone handles for harvesting grain and stone mortars and pestles for grinding it. Some groups lived in caves, others occupied incipient villages. They buried their dead with their personal ornaments in cemeteries. Carved bone and stone artwork have been found. [Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica ]

Matti Friedman wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Natufians were linked by characteristic tools, particularly a small, half-moon-shaped flint blade called a lunate,. They also showed signs of the “intentional cultivation” of plants, according to Ofer Bar-Yosef, professor of prehistoric archaeology at Harvard University, using a phrase that seems carefully chosen to avoid the loaded term “agriculture.” Other characteristic markers included jewelry made of dentalium shells, brought from the Mediterranean or the Red Sea; necklaces of beads made of exquisitely carved bone; and common genetic characteristics like a missing third molar. [Source: Matti Friedman, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2023]

See Separate Article: NATUFIANS (12,500-9500 B.C.): SETTLEMENTS, PROTO-AGRICULTURE, ARCHAEOLOGY factsanddetails.com ; NATUFIAN LIFE AND CULTURE (14,500-11,500 YEARS AGO) africame.factsanddetails.com

Jerf el Ahmar

Jerf el Ahmar is a Neolithic site on the Euphrates River in northern Syria,in northern Syria, which dates to between 9,200 and 8,700 B.C. It contained a sequence of round and rectangular buildings and is currently flooded by the Lake Assad following the construction of the Tishrin Dam. For five centuries, the site was occupied by the Mureybet culture, which had artifacts such as flint weapons and decorated small stones. The first transitions to agriculture in the region could be observed by the discovery of wild barley and einkorn. The first evidence of lentil domestication appears in the early Neolithic at Jerf el Ahmar. [Source: Wikipedia]

Jerf el-Ahmar contains a structure with an enormous 30-foot-in-diameter room. In the room is a bench with friezes of triangles. Believed to have been a meeting place built with collective labor, it seems plausible that it once sat at the center of a town. The site has also yielded evidence of ritual beheading, and cultivation and milling of grains, crossbreeding of crops such peas and lentils and the domestication of aurochs (wild oxen).

Trevor Watkins of the University of Edinburgh wrote: “There are at least three other early aceramic Neolithic settlement sites in the Euphrates valley in north Syria, contemporary with Jerf el Ahmar, that possessed similar buildings. They are large, circular, subterranean structures within the settlement, though each has distinctive features. The most distinctive is the circular structure of massive mudbrick that is emerging at Dja’de el Mughara. The building has massive internal buttresses, or stub-walls, whose mud-plastered surfaces are revealing painted, polychrome, rectilinear designs. These communal buildings clearly involved great investment of labour and the coordination of the skills and efforts of many of the community. [Source: Trevor Watkins, University of Edinburgh,“Household, Community and Social Landscape: Maintaining Social Memory in the Early Neolithic of Southwest Asia”, proceedings of the International Workshop, Socio-Environmental Dynamics over the Last 12,000 Years: The Creation of Landscapes II (14th –18th March 2011)” in Kiel January 2012 /+]

“It appears that the structures (those where the investigations and analysis have progressed sufficiently to inform us) were in use for a long time, though we as yet have no information as to what took place within them. It is a reasonable inference that their construction, maintenance, modification and repeated use served to perpetuate collective memory, something that will be pursued later. Even more remarkable are two sites that have the superficial appearance of settlements, but were central places to which many people came from a number of communities for specific purposes. /+\

Abu Hureyra — Where Agriculture First Developed?

Tell Abu Hureyra is a prehistoric archaeological site in the Upper Euphrates valley in Syria. Located in modern-day Raqqa Governorate on a plateau near the south bank of the Euphrates, 120 kilometers (75 miles) east of Aleppo, it was inhabited between 13,300 and 7,800 years ago in two main phases:Abu Hureyra 1, a village of sedentary hunter-gatherers; and Abu Hureyra 2, home to some of the world's first farmers during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period. The almost continuous sequence of occupation through the Neolithic Revolution has made Abu Hureyra one of the most important sites in the study of the origins of agriculture. [Source: Wikipedia]

The site is significant because the inhabitants of Abu Hureyra started out as hunter-gatherers but gradually moved to farming, making them the earliest known farmers in the world. Cultivation started at the beginning of the Younger Dryas period at Abu Hureyra. Evidence uncovered at Abu Hureyra suggests that rye was the first cereal crop to be systematically cultivated. In light of this, it is now believed that the first systematic cultivation of cereal crops was around 13,000 years ago.

During the Late Glacial Interstadial, Abu Hureyra site experienced climatic change. Due to lake level changes and aridity, the vegetation expanded into lower areas of the fields. Abu Hureyra accumulated vegetation that consisted of grasses, oaks, and Pistacia atlantica trees. The climate changed from warm and dry months to abruptly cold and dry months.

Abu Hureyra is a tell, or ancient settlement mound comprised of is a massive accumulation of collapsed houses, debris, and lost objects accumulated over the course of the habitation of the ancient village. The mound is nearly 500 meters (1,600 feet) across, 8 meters (26 feet) deep, and contained over 1,000,000 cubic meters (35,000,000 cubic feet) of archaeological deposits. Today the tell is inaccessible as its submerged beneath the waters of Lake Assad.

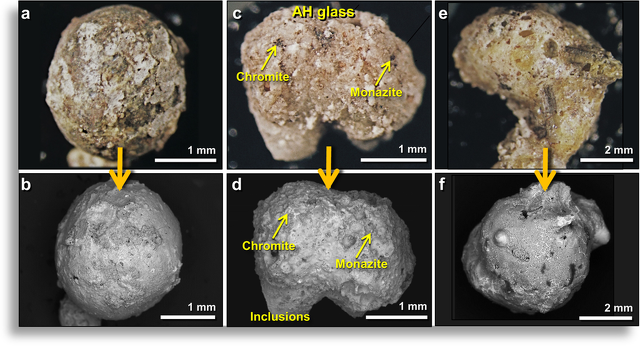

The site was excavated as a rescue operation before it was flooded by Lake Assad, the reservoir of the Tabqa Dam which was being built at that time. The site was excavated by Andrew M. T. Moore in 1972 and 1973. It was limited to only two seasons of fieldwork. Despite the limited time frame, a large amount of material was recovered and studied over the following decades. Since around 2012 Moore and others have published several papers reporting on meltglass, nanodiamonds, microspherules, and charcoal and high concentrations of iridium, platinum, nickel, and cobalt from the site of Abu Hureyra, which they attribute to an impact event that destroyed the village around 10,800 B.C.

Life at Abu Hureyra Site

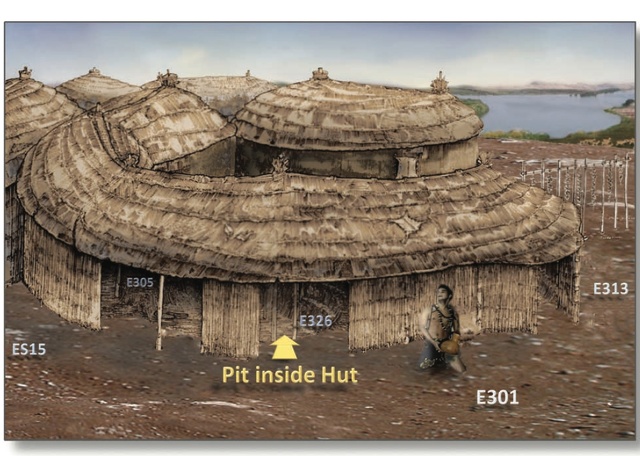

Tell Abu Hureyra was at the northern end of the area of Natufian culture (12,000 to 9,500 B.C.), near Mureybet. During the first settlement, Abu Hureyra 1, the village consisted of small round huts, cut into the soft sandstone of the terrace. The roofs were supported with wooden posts, and roofed with brushwood and reeds. Huts contained underground storage areas for food. The houses that they lived in were subterranean pit dwellings. The inhabitants are probably most accurately described as "hunter-collectors", as they didn't only forage for immediate consumption, but built up stores for longterm food security. They settled down around their larder to protect it from animals and other humans. From the distribution of wild food plant remains found at Abu Hureyra it seems that they lived there year-round. The population was small, housing a few hundred people at most—but perhaps the largest collection of people permanently living in one place anywhere at that time. [Source: Wikipedia]

The inhabitants of Abu Hureyra obtained food by hunting, fishing, and gathering of wild plants. Gazelle was hunted primarily during the summer, when vast herds passed by the village during their annual migration. These would probably be hunted communally, as mass killings also required mass processing of meat, skin, and other parts of the animal. The huge amount of food obtained in a short period was a reason for settling down permanently: it was too heavy to carry and would need to be kept protected from weather and pests.

Other prey included large wild animals such as onager, sheep, and cattle, and smaller animals such as hare, fox, and birds, which were hunted throughout the year. Different plant species were collected, from three different eco-zones within walking distance (river, forest, and steppe). Plant foods were also harvested from "wild gardens" with species gathered including wild cereal grasses such as einkorn wheat, emmer wheat, and two varieties of rye. Abu Hureyra 1 had a variety of crops that made up the system. Their resources consisted of 41 percent Rumex and Polygonum, 43 percent rye and einkorn, and the remaining 16 percent lentils. Several large stone tools for grinding grain were found at the site.

After 1,300 years the hunter-gatherers of the first occupation mostly abandoned Abu Hureyra, probably because of the Younger Dryas, an intense and relatively abrupt return to glacial climate conditions which lasted over 1,000 years, or because of the purported impact event. The drought disrupted the migration of the gazelle and destroyed forageable plant food sources. The inhabitants might have moved to Mureybet, less than 50 kilometers to the northeast on the other side of the Euphrates,[9] which expanded dramatically at this time. In comparison to Abu Hureyra 1, Abu Hureyra 2 had a different accumulation of resources, consisting of 25 percent Rumex/Polygonum, 3.7 percent rye/einkorn, 29 percent barley, 23.5 percent emmer, 9.4 percent wheat-free threshing, and 9.4 percent lentils.

Agriculture at Abu Hureyra

It is from the early part of the Younger Dryas that the first indirect evidence of agriculture was detected in the excavations at Abu Hureyra, although the cereals themselves were still of the wild variety. Some evidence has been found for cultivation of rye from 11050 B.C. in the sudden rise of pollen from weed plants that typically infest newly disturbed soil. Peter Akkermans and Glenn Schwartz found this claim about epipaleolithic rye, "difficult to reconcile with the absence of cultivated cereals at Abu Hureyra and elsewhere for thousands of years afterwards". It could have been an early experiment that didn't survive and continue. It has been suggested that drier climate conditions resulting from the beginning of the Younger Dryas caused wild cereals to become scarce, leading people to begin cultivation as a means of securing a food supply. Results of recent analysis of the rye grains from this level suggest that they may actually have been domesticated during the Epipalaeolithic. It is speculated that the permanent population of the first occupation was fewer than 200 individuals.[15] These individuals occupied several tens of square kilometers, a rich resource base of several different ecosystems. On this land they hunted, harvested food and wood, made charcoal, and may have cultivated cereals and grains for food and fuel.[15]

The first domesticated morphologic cereals came about at the Abu Hureyra site around 10,000 years ago. The village of Abu Hureyra had impressive agricultural advances for the time period. The rapid growth of farming led to the development of two different domesticated forms of wheat, barley, rye, lentils, and more due in part to a sudden cool period in the area. The cool period affected the supply of wild animals such as gazelle, which at the time was their main source of protein. Since their food supply became scarce it was critical that they find a way to provide for the population, this led to extensive agricultural efforts as well as the domestication of sheep and goats to provide a steady protein source. Another helpful factor was the ability to grow legumes, which fix nitrogen levels in the soil. This improved the fertility of the soil and allowed for the crop plants to flourish.

This massive increase in agriculture had a cost. Those who lived in the village of Abu Hureyra experienced several injuries and skeletal abnormalities. These injuries mostly came from the way the crops were harvested. In order to harvest the crops the people of Abu Hureyra would kneel for several hours on end. The act of kneeling for long durations would put the individuals at risk for injuring the big toes, hips, and lower back. There was cartilage damage in the toe that was so severe the metatarsal bones would rub together. In addition to this injury another common injury was for the last dorsal vertebra to be damaged, crushed, or out of alignment due to the pressure used during the grinding of grains. These skeletal abnormalities also can be found on the teeth of the Abu Hureyra people. Since the grain was stone ground many flakes of stone would still be left in the grain which over time would wear down the teeth. In rare cases women would have large grooves in their front teeth which suggests they used their mouth as a third hand while weaving baskets. This dates basket weaving as far back as 6500 B.C. and the fact so few women had these grooves shows that basket weaving was a rare skill to have.These baskets were extremely important to the success of the agriculture because the baskets were used to collect or spread seeds, and were also used to collect or distribute water.

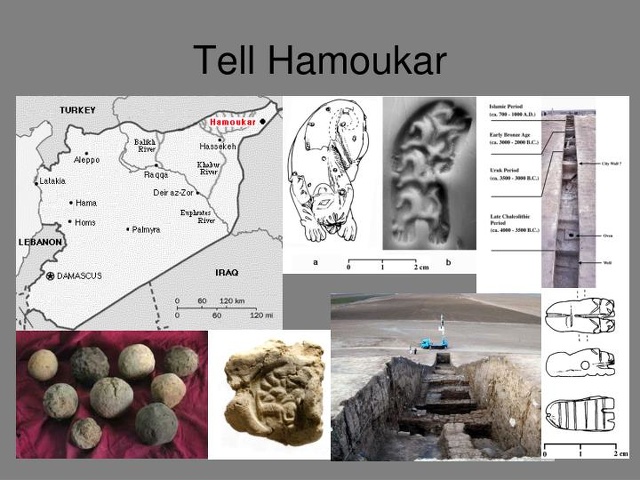

Tell Hamoukar

Tell Hamoukar is an interesting 6000-year-old site in eastern Syria near the border of Iraq and Turkey. With a central city covering 16 hectares, it is as highly developed as sites in southern Iraq such as Uruk and Nippur and seems to debunk the theories that ancient civilization developed in southern Iraq and spread northward and westward. Instead Tell Hamoukar is offered as proof that several advanced ancient civilizations developed simultaneously in different parts of the Middle East. [Source: Natural History magazine, Clemens Reichel of the Oriental Institute of Chicago]

Excavations indicate that Tell Hamoukar was first inhabited around 4000 B.C. perhaps as early as 4500 B.C. By around 3700 B.C. is covered at least 13 hectares and displayed signs of an advanced civilization: a 2.5-meter-high, 3.4 -meter-wide defensive wall, large scale bread making and meat cooking, a wide array of cylinder seals, presumably used to mark goods. Many seals were used to secure baskets and other containers of commodities.

The simplest seals had only simple markings. More elaborate ones had kissing bears, ducks and a leopard with 13 spots. Scholars believed that more elaborate seals were used by people of high status and indicate a hierarchically-ordered society. But as advanced as Tell Hamoukar and other places in the area were they are not regarded as advanced as those in southern Iraq, where writing developed.

Tell Hamoukar contains a 500-acre site with buildings with huge ovens, which offer evidence that people were making food for other people. The city seems to have been a manufacturing center for tools and blades that utilized obsidian supplies further north and supplied the tools throughout Mesopotamia to the south. Other sites being excavated in northern Syria include Tell Brak and Habuba Kabira, both of which appear to be much larger than previously thought.

A team led by Clemens Reichel of the Oriental Institute of Chicago and Syrian Department of Antiquities have been excavating Tell Hamoukar since 1999.. Guillermo Algaze of the University of California, San Diego is an archaeologist that specialize in north-south relations in Mesopotamia.

See Separate Article: NEOLITHIC TELL SITES IN SYRIA: URBANIZATION, WARFARE AND TIES TO URUK AND THE SUMERIANS africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Live Science, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. The Independent, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024