Home | Category: First Cities, Archaeology and Early Signs of Civilization

NEOLITHIC JORDAN

The Neolithic period (8000-4000 B.C.) is when people began relying less on wild resources and began manipulating their environment more, particularly in the form of farming and domesticating animals. Jordan was at the the center of this revolution. Some of the world’s oldest settlements, civilizations and different were established there. [Source: Welcome Jordan]

During the Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, in present-day Jordan, three great changes took place: 1) First, people settled down in communities and small villages. This corresponded with the introduction of grain agriculture, domesticated peas and lentils, and the newly-widespread practice of goat herding. The combination of settled life and "food security" led to a sigprompted a significant rise in population which reached into the tens of thousands. 2) The second basic shift in settlement patterns was prompted by climate change. The deserts of Jordan area grew warmer and drier over time, becoming virtually uninhabitable throughout much of the year from 8,500 to 7,500 years ago. This created two divisions: the desert in the east and the "sown" areas to the west. 3) One of the most significant development of the late Neolithic period (5500-4500 B.C.) was the making of ceramic pottery. Before this time pottery was fashioned from plaster. It appears that the technology to systematically make vessels from clay was introduced to the area by people from Mesopotamia, to the northeast.

In the earliest Neolithic age (the pre-Pottery Neolithic A, 10,000 – 8800 B.C.) people began to live in more permanent settlements. Bill Finlayson wrote: In order to stay in one place they established these settlements at the junction between different environments, so that they could obtain food from many different habitats without having to move. The site of Wadi Faynan 16 is a good example, being located at the mouth of the Wadi Ghuwayr, giving people easy access to the river and its resources, a route up into the mountains, at the same time as looking out over the Wadi Araba. People also made it easier to stay in one place by beginning to sow and harvest wild plants such as barley. At Dhra’, situated in a similar location at the base of the mountains leading up to Kerak, people began to build granaries, allowing them to store the harvest and consume the grain over the rest of the year. [Source: Bill Finlayson, “The First Villages. The Neolithic Period (10,000-4500 B.C.)”,”Atlas of Jordan”, Open Edition Books, 2014]

In the next period (the Pre-Pottery Neolithib, (8800–6500 B.C.) the wild animals and plants that had been increasing controlled, gradually became domesticated, and the old geographical positions were no longer required. Settlements spread over much of Jordan as population rose with the new food sources. At the beginning of the period people still lived in small settlements with circular architecture, such as at Beidha and Shkarat Msaied, although this became more elaborate and solid. By the end of the period, settlements had become large and densely packed, famously so at the mega sites of Ayn Ghazal and Basta, made of rectangular buildings with little space between them. The rising importance of farming led people to place these large settlements along the edge of the Jordanian plateau, in a similar setting to where modern agriculture is practiced. Small sites began to appear in the arid areas of Jordan, such as the Jafr basin, where crops were probably being grown in temporary settlements, from where food may have been brought back to the large sites to help feed the rising populations. By the end of the period, pastoral economies had begun to develop, with some of the population taking their animals into the arid zone, and only returning for part of the year to the permanent settlements. This development was very important for Jordanian history, as it provided the roots of the relationship between nomadic pastoralists and settled farmers.

The system of major sites collapsed, probably due to a combination of climate change affecting environments around these large sites that had been over exploited by a mixture of tree felling (to use as fuel for both domestic and industrial purposes, and for architecture) and goat herding to sustain the large settled populations, with no developed understanding of soil management. Around that time a new phase started (the Late Neolithic, or Pottery Neolithic period). Ceramic Neolithic or Pottery Neolithic, is the final part of the Neolithic period. It followed PPNB and is sometimes further divided into Pottery Neolithic A (PNA) and Pottery Neolithic B (PNB) phases. The Late Neolithic period in Southwest Asia began with the first experiments with pottery, around 7000 B.C. and lasted until the discovery of copper metallurgy and the start of the Chalcolithic (Copper Age) around 4500 B.C. Again, settlement patterns changed. One significant change was that instead of the focus being on the large sites, many people dispersed into small settlements, that we can understand as agricultural villages. Another change was that people moved into more open country, such as Tell Wadi Faynan, set in the middle of what are still used as agricultural fields. Another big change to the landscape was the first real signs of what many would understand as farming, the building of terraces to hold soil, and the spreading of domestic rubbish to fertilise the soil. Some famous Jordanian sites, such as Pella, seem to have first been occupied in this period.

RELATED ARTICLES:

STONE AGE PALESTINE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NEOLITHIC SITES IN ISRAEL-PALESTINE: LARGE, OLD AND UNDERWATER SITES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NEOLITHIC ISRAEL-PALESTINE: CULTS, SPIRIT MASKS AND EARLY URBANIZATION africame.factsanddetails.com ;

JERICHO: HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGY, PEOPLE, PLASTERED SKULLS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NEOLITHIC SITES IN SYRIA africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Prehistoric Archaeology of Jordan (BAR International) by Donald O. Henry (2000) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Cultural Ecology and Evolution: Insights from Southern Jordan” by Donald O. Henry (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Spring of the Gazelle an Early Neolithic Society” by Kemal Yildirim (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Early Prehistory of Wadi Faynan, Southern Jordan: Archaeological Survey of Wadis Faynan, Ghuwayr and Al Bustan” by Bill Finlayson and Steven Mithen (2014) Amazon.com;

“Early Village Life at Beidha, Jordan: Neolithic Spatial Organization and Vernacular Architecture: The Excavations of Mrs. Diana Kirkbride-Helbæk” by Brian F. Byrd (Author) Amazon.com;

“Life in Neolithic Farming Communities: Social Organization, Identity, and Differentiation” by Ian Kuijt (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Revolution in the Near East: Transforming the Human Landscape”

by Alan H. Simmons and Dr. Ofer Bar-Yosef (2011) Amazon.com;

“Natufian Foragers in the Levant: Terminal Pleistocene Social Changes in Western Asia” by Ofer Bar-Yosef and François R. Valla (2013) Amazon.com;

“Early Urbanizations in the Levant: A Regional Narrative” by Raphael Greenberg (2002) Amazon.com;

“Jericho: Dreams, Ruins, Phantoms” by Robert Ruby (1995) Amazon.com;

“Excavations at Jericho Volume Three: The Architecture and Stratigraphy of the Tell”

by Kathleen M. Kenyon and T. A. Holland Amazon.com;

“Dame Kathleen Kenyon: Digging Up the Holy Land (UCL Institute of Archaeology Publications) by Miriam C Davis (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Leopard's Tale” by Ian Hodder (2006) Amazon.com;

“Peopling the Landscape of Çatalhöyük: Reports from the 2009-2017" by Ian Hodder Amazon.com;

“Projectile Points, Hunting and Identity at Neolithic Çatalhöyük, Turkey”

by Lilian Dogiama (2023) Amazon.com;

“Religion at Work in a Neolithic Society: Vital Matters” by Ian Hodder Amazon.com;

“Religion in the Emergence of Civilization” by Ian Hodder (2010) Amazon.com;

“Dolní Vestonice–Pavlov: Explaining Paleolithic Settlements in Central Europe”

by Jirí A. Svoboda Amazon.com;

“The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World” by David W. Anthony (2010) Amazon.com;

First Hominins in Jordan

Jordan is rich in archaeological remains from the Paleolithic periods. The Levant, in general, and Jordan, in particular, was located at the cross-roads between Africa, Europe and Asia, so that at least some of periodic expansions out of Africa passed through the region. The oldest prehistoric sites — such as Ubeidiya, on the west bank of the Jordan River south of Lake Tiberias — date back to 1.5 million years ago. During the Paleolithic periods hunter gatherers traveled from place to place looking for food and non-food resources. They lived in both open-air locations and caves. Most Paleolithic research in Jordan is in the Western Highlands, the Southern Mountain Desert and the Azraq Basin. Here, early archaeological sites are largely associated with lakeshore environments in areas with East African flora and fauna in what were grassland savannas over much of the Pleistocene.[Source: Maysoun al-Nahar, “Atlas of Jordan”, Open Edition Books, 2014]

The Lower Paleolithic of Jordan (1.5 million to 250,000 years ago) is characterized by the appearance of the earliest hominin stone artifacts late and associated with Homo erectus. The most important Lower Paleolithic sites and other occurrences in Jordan are in the Western Highlands and southern deserts at 1) the Mashari‘ site cluster in the Tabaqat Fahl Formation, exposed in the Wadis Hammeh, Himar and Hamma, near Pella; 2) Abu Habil, some 15 kilometers to the south; 3) the upper Wadi Zarqa, north of Amman; 4) Fjaje near Shawbak, in the Wadi Bustan, and 5) the Judayid Basin below the Ras al-Naqb escarpment, north of the port city ofAqaba.

Diring the Middle Paleolithic (150,000 to 45,000 years ago), Neanderthals lived in what is now Jordan and Homo sapiens (modern humans) showed up. Maysoun al-Nahar wrote: Although most of the Middle Paleolithic sites in Jordan are heavily deflated, some sites remain in situ, such as Ayn Dufla, Tor Sabiha and Tor Faraj Rockshelters in the Wadi al-Hasa, C Spring and Ayn Soda in the Azraq Basin, Abu Habil in the Jordan Valley, and various sites in the Jafr Basin, Wadi Hisma and Ras al-Naqb areas of southern Jordan. They are defined techno-typologically as related to the Levantine Mousterian Complex with extensive use of Levallois technology,

In the Middle Palaeolithic many of the above-mentioned locations were characterized by lakes, marshes and seasonal ponds with both arboreal (e.g., Quercus) and riparian vegetation (e.g., Cyperus). The early part of the Middle Paleolithic, based on pollen evidence from Ain Difla in the Wadi al-Hasa, appears to have been relatively cool and dry, although more moist than modern conditions in this region. For example, fauna assemblages from these sites include gazelle, equids, and ostrich at Tor Faraj and equids, caprines or ibex, and gazelle at Ayn Dufla.

Modern Humans in Jordan

During Upper Paleolithic (45,000 to ca 20,000 years ago), anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens), lived in Jordan. Maysoun al-Nahar wrote: In comparison to earlier Palaeolithic periods, Jordan has many in situ Upper Paleolithic sites. They are found either as open-air sites or rockshelters, such as Jebel Qalkha and Wadi Humayma in the Wadi Hisma, Ayn Buhaira open-air site and Yutil al-Hasa Rockshelter in the Wadi al-Hasa, Wadi al-Jilat 9, Uwaynid 18, and Wadi Enoqiyya in the Azraq area, and Wadi Hamma in the Jordan Valley. [Source: Maysoun al-Nahar, “Atlas of Jordan”, Open Edition Books, 2014]

Two major lithic technological complexes characterize sites of the southern Levant during the Upper Paleolithic period. They are the Ahmarian and the Levantine Aurignacian. While Ahmarian sites are known from sites in Jordan, Levantine Aurignacian ones have not yet been found. Upper Palaeolithic sites are attributed to the Ahmarian by the predominance of a blade/bladelet technology that emphasized the production of Microliths (such as Ouchtata bladelets) and al-Wad points, as well as different types of endscrapers and burins.

Archeological evidence indicates that the climate during the early Upper Paleolithic was slightly moister than the late Middle Paleolithic. Conditions became drier throughout the Upper Paleolithic. Nevertheless, the appearance of the high water tables in the highlands increased spring flow and continued to feed numerous lakes, marshes and seasonal ponds here. In the Azraq Basin, faunal assemblage from Jilat and Uwaynid are characterized by steppe and sub-desert environments, but those from the vicinity of the Azraq Oasis suggest the persistence of nearby springs and tracts of marshland.

Epipalaeolithic Period (23,000–11,600 Years Ago) in Jordan

The Epipalaeolithic (EP) period (ca. 23,000 - 11,600 years ago) in Jordan documents a remarkable series of transitions from mobile hunter-gatherers in the Upper Palaeolithic to sedentary food-producing villagers in the Neolithic. Lisa A. Maher wrote: Throughout the EP, societies undergo dramatic changes in social organization, technology, economy and ideology. Most notably, we find the first domestic animals (dogs), formalised cemeteries, early semi-sedentary sites, and the appearance of mega-sites where large groups congregated repeatedly. These mega-sites became significant places in the landscape foundational to the establishment of later Neolithic farming villages. [Source: Lisa A. Maher, “Atlas of Jordan”, Open Edition Books, 2014]

EP groups are known for producing small (microlithic) stone tools formed into a variety of shapes and hafted into multi-purpose composite tools. They subsisted on hunted game, wild plants and, more rarely, aquatic resources. The period can be divided roughly into three phases; Early, Middle and Late. However, within each phase several localised industries are known. The most well-known of these are the Kebaran (early), characterised by narrow micropoints and obliquely truncated bladelets; the Geometric Kebaran (middle) with a shift towards the production of geometric microliths, especially trapeze/rectangles; and the Natufian (late) identified by high frequencies of lunates, along with arched and straight-backed bladelets and microburins (specialised by-products of bladelet segmentation).

EP sites are found throughout Jordan; however, the nature and density of occupation changes over time. Our knowledge of settlement and society during this period in Jordan comes from two primary sources: intensive regional surveys in Wadi al-Hasa, the Azraq Basin and Black Desert, Wadi Ziqlab, Wadi al-Hamma, and southern Jordan, as well as excavation at several sites within these study areas.

In the Early EP small sites are found in caves or rockshelters and in open-air settings of western Jordan and the Azraq Basin. Sites such as Tor al-Tareeq and Ayn Qasiyya were likely tied to large permanent lakes supported by the wet climate of the Last Glacial Maximum and groups took advantage of the varied wildlife that flourished at these ‘oases’. In addition, the region’s first mega-sites appear in Jordan in the early EP. Kharana IV and Jilat 6 are anomalous because of their size — each covers ~20,000 square meters — and their incredibly high densities of lithics, fauna, groundstone and pierced marine shells.. They also document hut structures, hearths, living floors and burials. At Kharana IV, differences in tool technology between phases indicates that several groups occupied the site over thousands of years; while cementum analyses of gazelle teeth from layers within the same phases indicates that site occupations likely extended over multiple seasons.

World's Earliest Buildings Made 20,000 Years Ago in Jordan?

Some of the earliest evidence of prehistoric architecture has been found in the Jordanian desert. In 2012, archaeologists said they had found Jordan’s earliest buildings, dated to approximately 20,000 years ago. Cambridge University reported: “Archaeologists working in eastern Jordan have announced the discovery of 20,000-year-old hut structures, the earliest yet found in the Kingdom. The finding suggests that the area was once intensively occupied and that the origins of architecture in the region date back twenty millennia, before the emergence of agriculture. The research, published 15 February, 2012 in PLoS One by a joint British, Danish, American and Jordanian team, describes huts that hunter-gatherers used as long-term residences and suggests that many behaviours that have been associated with later cultures and communities, such as a growing attachment to a location and a far-reaching social network, existed up to 10,000 years earlier. [Source:Cambridge University, February 18, 2012]

“Excavations at the site of Kharaneh IV are providing archaeologists with a new perspective on how humans lived 20,000 years ago. Although the area is starkly dry and barren today, during the last Ice Age the deserts of Jordan were in bloom, with rivers, streams, and seasonal lakes and ponds providing a rich environment for hunter-gatherers to settle in. “What we witness at the site of Kharaneh IV in the Jordanian desert is an enormous concentration of people in one place,” explained Dr Jay Stock from the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Cambridge and co-author of the article. “People lived here for considerable periods of time when these huts were built. They exchanged objects with other groups in the region and even buried their dead at the site. These activities precede the settlements associated with the emergence of agriculture, which replaced hunting and gathering later on. At Kharaneh IV we have been able to document similar behaviour a full 10,000 years before agriculture appears on the scene.”

The archaeologists spent three seasons excavating at the large open-air site covering two hectares. They recovered hundreds of thousands of stone tools, animal bones and other finds from Kharaneh IV, which today appears as little more than a mound 3 meters high rising above the desert landscape. Based on the size and density of the site, the researchers had long suspected that Kharaneh IV was frequented by large numbers of people for long periods of time; these latest findings now confirm their theory. “It may not look very impressive to the untrained eye, but it is one of the densest and largest Palaeolithic open-air sites in the region,” said Dr Lisa Maher, from the University of California, Berkeley, who spearheads the excavations. “The stone tools and animal bone vastly exceed the amounts recovered from most other sites of this time period in southwest Asia.” In addition, the team also recovered rarer items, such as shell beads, bones with regularly incised lines and a fragment of limestone with geometric carved patterns.

“So far, the team has fully excavated two huts; but there may be several more hidden beneath the desert’s sands. “They’re not large by any means. They measure about 2–3 meters in maximum length and were dug into the ground. The walls and roof were made of brush wood, which then burnt and collapsed leaving dark coloured marks,” described Dr Tobias Richter from the University of Copenhagen and one of the project’s co-directors. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the hut is between 19,300 and 18,600 years old. Although a team of archaeologists working at Ohalo II on the shore of the Sea of Galilee (Israel) in 1989 found the region’s oldest hut structures, which date from 23,000 years ago, the team working at the Kharaneh IV site believe their discovery is no less significant, as Dr Maher explained: “Inside the huts, we found intentionally burnt piles of gazelle horn cores, clumps of red ochre pigment and a cache of hundreds of pierced marine shells. These shell beads were brought to the site from the Mediterranean and Red Sea over 250 kilometers away, showing that people were very well linked to regional social networks and exchanged items across considerable distances.”

Natufians

The Natufian culture refers to mostly hunter-gatherers who lived in modern-day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria approximately 15,000 to 11,500 years ago. Merging nomadic and settled lifestyles, they were among the first people to build permanent houses and cultivate edible plants. The advancements they achieved are believed to have been crucial to the development of agriculture during the time periods that followed them.

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica: Mainly hunters, the Natufians supplemented their diet by gathering wild grain; they likely did not cultivate it. They had sickles of flint blades set in straight bone handles for harvesting grain and stone mortars and pestles for grinding it. Some groups lived in caves, others occupied incipient villages. They buried their dead with their personal ornaments in cemeteries. Carved bone and stone artwork have been found. [Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica ]

Matti Friedman wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Natufians were linked by characteristic tools, particularly a small, half-moon-shaped flint blade called a lunate,. They also showed signs of the “intentional cultivation” of plants, according to Ofer Bar-Yosef, professor of prehistoric archaeology at Harvard University, using a phrase that seems carefully chosen to avoid the loaded term “agriculture.” Other characteristic markers included jewelry made of dentalium shells, brought from the Mediterranean or the Red Sea; necklaces of beads made of exquisitely carved bone; and common genetic characteristics like a missing third molar. [Source: Matti Friedman, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2023]

Lisa A. Maher wrote: In the Middle EP sites are found throughout the country as groups expanded territory and density of occupation. The first burial grounds with complex mortuary treatments, such as at Uyun al-Hammam, hint at the growing symbolic role of animals in social life as seen at later Natufian and Neolithic sites. The mega-sites continued to be occupied and base camps were also established in the west. In the Late EP (Natufian) the mega-sites are abandoned, probably due to increasing dry and hot conditions; however, groups establish more permanent settlements throughout the region, with stone-built structures and toolkits suggestive of much more intensive exploitation of particular plant resources such as cereals, tying groups to particular locations. At sites such as Wadi al-Hamma 27 we see all the hallmarks of large Natufian base camps, including circular stone structures, high densities of ground stone and plant remains, symbolic and decorative objects (such as a large basalt monolith carved with a geometric motif), toolkit caches, organisation of site activities, and human burials. [Source: Lisa A. Maher, “Atlas of Jordan”, Open Edition Books, 2014]

The EP period is of interest to those studying the origins of social complexity as it exhibits many early instances of features integral to understanding the development of hierarchical societies yet to come; the first domestic dog, extensive long-distance trade networks, exchange of non-local goods, sedentary base camps with storage facilities and stone architecture, thick deposits with multi-seasonal occupation, non-portable ground stone, also a rich bone tool and art industry, intensified plant use, and formal cemeteries. Although these features appear individually throughout the EP and don’t culminate until the Natufian, their presence emphasizes that the practices of the Neolithic have their origins much earlier.

See Separate Article: NATUFIANS (12,500-9500 B.C.): SETTLEMENTS, PROTO-AGRICULTURE, ARCHAEOLOGY factsanddetails.com ; NATUFIAN LIFE AND CULTURE (14,500-11,500 YEARS AGO) africame.factsanddetails.com

11,700-Year-Old Community Center in Wadi Faynan

According to Archaeology magazine: At Wadi Faynan in southern Jordan, excavations of a site belonging to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A culture suggest that the first buildings weren't necessarily homes or ritual spaces — but rather community centers for shared work. An oval-shaped mud building at the site, which dates to over 11,000 years ago, had mortars set into the floor, perhaps to process cultivated wild plants. Archaeologists believe there was little distinction between domestic and ritual spaces. Such divisions would come later, alongside the advent of agriculture. [Source: Archaeology magazine, September-October 2011]

The discovery of the remains of the 4,500-square-foot structure at Wadi Faynan is helping redefine the purpose of architecture at the point in history when roving bands of hunter-gatherers transitioned to sedentary societies. Rather than characterizing early Neolithic settlements dating to nearly 12,000 years ago as residential clusters tied to the advent of agriculture, structures such as the tower at Jericho on the West Bank and Göbekli Tepe in southern Turkey suggest an initial stage of settlement where people coalesced around communal activities and rituals. [Source: Archaeology magazine, Volume 65 Number 1, January-February 2012[Source: Nikhil Swaminathan

“Add to that list the oval-shaped building at Wadi Faynan, known simply as O75. It dates to 11,700 years ago and, according to Bill Finlayson, director of the Council for British Research in the Levant, who led its excavation, "it appears to have been built by digging a pit and then lining the walls with a very strong mud mixture." A floor was constructed from mud plaster and surrounded by two tiers of benches, three feet deep and one-and-a-half feet high, recalling an amphitheater. Postholes indicate that a roof covered a section of the structure.

“Some finds, including mortars for grinding found in raised platforms at the structure's center, suggest people of the time might have used the building as a venue to collectively process plants, such as barley and pistachio. O75 may have additionally offered a space for communal gatherings. "It could have been a locale where small groups of people were aggregating on a periodic basis," says A. Nigel Goring-Morris, a prehistoric archaeologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem who was not involved in the excavation.

Ain Ghazal

Ain Ghazal, an archeological site in Amman, Jordan was one of the largest population centers in the Middle East from 7200 to 5000 B.C., a period in human history when semi-nomadic hunters and gathers were adapting to farming and animals herding and organizing themselves into cities. The name Ain Ghazal (Gazelle’s Spring) is derived from a spring from which people in ancient times and today took their drinking water. The site extends past both banks of al-Zarqa’ river. Early Ain Ghazal was set on terraced ground on a valley-side. Evidence recovered from the excavations suggests that much of the surrounding countryside was forested and offered the inhabitants a wide variety of economic resources. Arable land is plentiful and closeby, which os atypical of many major Neolithic sites in the Near East. It seems that the region was rich in gazelles. Archaeologists found 13 gazelle horn cores in a room in a single building.

Ain Ghazal (also spelled Ein Ghazal and Ayn Ghazal) covers about 12 hectares (30 acres) and is located in metropolitan Amman, Jordan, about two kilometers (1.24 miles) north-west of Amman Civil Airport. At its peak Ain Ghazal was comprised of many buildings, which were divided into three distinct districts. The mud-brick houses were rectangular in shape and contained square main room and a smaller anteroom. Walls were plastered with mud on the outside, and with lime plaster inside that was renewed every few years. The stone tower and walls found at Jericho show that defense were found at Neolithic settlements at that time.

Ain Ghazal was established around 10,000 years ago when hunter-gatherers villages were well established and organized agricultural society and animal domestication were just beginning It is located in the eastern part of Amman, a junction where the inhabitants of the mountainous regions in the west and the Jordanian Badiya in the east meet. The site played an important role in the communication and the interaction between the people of those two regions throughout several epochs. [Source: Zeidan Kafafi,“Atlas of Jordan”, p. 111-113, Open Edition Books, 2014]

The history of Ain Ghazal is divided into two phases. Phase I starts around 8,300 B.C. and ends around 7,950 B.C.. Phase II last 7,950 B.C. to 7,550 B.C.. At its peak around 7000 B.C., the site covered over 10 to 15 hectares (25 to 37 acres) and was inhabited by around 3,000 people — four to five times more than Jericho. After 6500 B.C. however, the population dropped sharply to about 500 people within only a few generations, probably due to severe dry conditions that resulted from a climatic event 8,200 years ago. [Source: Wikipedia]

Zeidan Kafafi wrote: Ain Ghazal began as a farming village, with an area not exceeding 2 hectares. It developed and extended over time until it reached an area of 15 hectares between 7500-7000 B.C.. It continued to be inhabited continuously for around 3000 years. The archaeological material found at Ain Ghazal indicates that its inhabitants had access to a wide range of local and exotic resources within geographically-extensive trade and social networks, and exhibited rich and complex ideological, symbolic and cultural practices.

People of Ain Ghazal

The people of Ain Ghazal were farmers and hunters and gatherers. They used stone tools and weapons and made clay figures and vessels. They lived in multi-room houses with stone walls and timber roof beams and cooked in hearths. Plaster with decorations covered the walls and floors. They ate meat and milk products from goats, grew wheat barely, lentils, peas and chickpeas, hunted wild cattle, boar and gazelles and gathered wild plants, almonds, figs and pistachios.

Ain Ghazal figure

Zeidan Kafafi wrote: The excavated remains of Ain Ghazal indicate architectural development and diversification throughout its several stages of settlement. Excavators recognized two main types of constructions: houses and religious buildings. In the eastern and northern portions of the site, excavators found buildings that, judging from their architectural styles, seem to be dedicated to religious rites. Researchers also found objects related to these practices, such as plastered skulls, masks, and human and animal representations. [Source: Zeidan Kafafi,“Atlas of Jordan”, p. 111-113, Open Edition Books, 2014]

Before the adoption of pottery, people in Ain Ghazal utilized containers made of limestone, lime plaster, and other types of stone. Querns or hand mills, used to grind cereals, were made of basalt or limestone. C. 6500 B.C. fired pottery became commonly used. Pottery types common to the occupants of Ain Ghazal included pots, plates and cups used to cook, store or serve food.

Y-DNA haplogroup E1b1b1b2 has been found in 75 percent of the ʿAin Ghazal population and and in most Natufians. T1a (T-M70) is found among the later Middle Pre-Pottery Neolithic B inhabitants from ʿAin Ghazal. Currently, this is the oldest known sample ever found at any ancient site and wasn't found among the early and middle era populations. Therefore it is thought that the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B population is mostly composed of two different populations: members of early Natufian civilisation and a population resulting from immigration from the Fertile Crescent likely Iraq or possibly south-eastern Anatolia. [Source: Wikipedia]

Life of the People of Ain Ghazal

The diet of the inhabitants Ain Ghazal was varied. Domesticated plants included wheat and barley species, but legumes (primarily lentils and peas) appear to have been the primary staple. Wild plants were also consumed. The determination of whether the animals consumed were domesticated or wild is a topic of much debate. Goats were important animals. They were used in a domestic sense, although they may not have been morphologically domestic. Many of the phalanges recovered exhibit pathologies that are suggestive of tethering. A wide range of wild animal species were consumed at the site. Over 50 different species have been identified, including gazelle, aurochs, wild pigs and foxes.

Although farming was the main economic activity at Ain Ghazal, hunting continued to be important. People continued to manufacture arrowheads out of flint, in order to hunt animals. They also used flint to make other tools such as axes, adzes, knives, sickle blades, drills, and scrapers for skin or wood.

Archeologists working in Ain Ghazal found what they say may be the world’s oldest known game. The game board, a limestone slab, has two sets of circular depressions and bears a striking resemblance to games played in the Middle East today with counting stones. The slab was found in a house, and because it seemed to serve no utilitarian or ceremonial function archeologists concluded it most likely was a game board. [National Geographic Geographica, February 1990].

At around 16,500 years old, the cemetery at Uyun al-Hammam is the oldest known in the Middle East. Recent excavations have uncovered the remains of at least 11 people. The remains of a red fox were also found, separated between two human graves, and with the bones of other animals. Later burials sometimes included dogs in the same way, so this fox may have been a pet or hunting companion. [Source: Archaeology magazine, May-June 2011]

Ain Ghazal Burial Practices

The mortuary practices of Ain Ghazal have been extensively studied. Post-mortem skull removal, was commonly restricted to just the cranium, but occasionally the mandible, and apparently followed preliminary primary interments of the complete corpse. Such treatment has commonly been interpreted as representing rituals connected with veneration of the dead or some form of "ancestor worship". [Source: Wikipedia]

There is evidence of class in the way the dead were treated. Some people were buried in the floors of their houses. After the flesh had wasted away, often the head was later retrieved and the skull buried in a separate shallow pit beneath the house floor. Some skulls were decorated. This could have been either a form of respect or so that they could impart their power to the house and the people in it. The corpses of some people were thrown on trash heaps and their bodies remain intact, indicating that not every deceased was ceremoniously honored after death. Scholars have estimated that a third of adult burials were found in trash pits with their heads intact. Why only some of the inhabitants were properly buried and others simply disposed of remains unresolved. Burials seem to have taken place approximately every 15–20 years, indicating a rate of one burial per generation, though gender and age were not constant in this practice.

Spanish researchers, led by Juan Ibáñez of the Milà y Fontanals Institution of the Spanish National Research Council, excavating near Amman and Ain Ghazal, discovered a collection of over a hundred 10,000-year-old flint objects that appear to be small human figures. The scientists reported their findings in an article published in 2020 in the journal Antiquity and speculated that perhaps the flint figures were representations of the recently deceased and, were part of a very early ancestor cult. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 26, 2020]

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: They the were digging at Kharaysin when they came across the roughly two inch-long figures....The flint images themselves aren’t much to look at: they are shaped like lumpy violins. Flint was commonly used during the Neolithic period to make weapons and tools, but a lack of wear and tear on these objects suggests that they were never put to any kind of practical utilitarian use. Similarities with another cache of more obviously human figurines from nearby ‘Ain Ghazal have led the research team to conclude that they are representations of human bodies. The fact that the figurines were found close to burial sites suggests that the human figures “were manufactured and discarded during mortuary rituals and remembrance ceremonies that included the extraction, manipulation and redeposition of human remains.”

Ain Ghazal Art

Archaeologists have unearthed skulls covered with plaster and with bitumen in the eye sockets at sites throughout Jordan, including Ain Ghazal and Beidha as well as in Palestine and Syria. Fairly recently, archaeologists finished restoring what may be one of the world's oldest statuess. Found at Ain Ghazal and estimated to be 8000 years old, it is just over one meter high and is of a woman with huge eyes, skinny arms, knobby knees and carefully depicted toes. [Source: Welcome Jordan]

In the earlier levels at ʿAin Ghazal there are small ceramic animals and human figures that seem to have been used as personal or familial ritual figures. The animal figures are of horned animals and the front part of the animal is the most clearly modeled. They give the impression of dynamic force. Some of the animal figures have been stabbed in their vital parts and then buried in the houses. Other figurines were burned and then discarded with the rest of the fire. [Source: Wikipedia]

The people of Ain Ghazal built ritual buildings and used large figurines or statues. It has been suggested that the building of the statues and buildings was a way for an elite group to demonstrate and underline its authority over those who owe the provide labor to the community.In addition to the larger statues, small clay and stone tokens, some incised with geometric or naturalistic shapes, were found at ʿAin Ghazal.

A total of 195 figurines (40 human and 155 animal) have been recovered from early Ain Ghazal levels. The vast majority of figurines are of cattle, a species that account for only 8 percent of the animal bones found at the site. This seems to illustrate importance of hunted cattle. It has also been suggested that the statues show the importance of hunters who hunt cattle –- likely a group activity

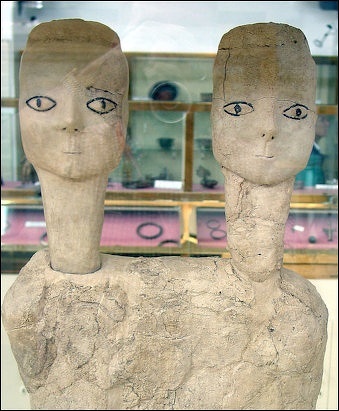

Ain Ghazal's Other-Worldly Figures

Mysterious human figures unearthed at Ain Ghazal, are also among the oldest human statues ever found. Made of lime plaster and dating back to 7000 B.C., the figures were about 3½ feet tall and have bitumen accented eyes and look like aliens from outer space. Scholars believe they played a ceremonial role and may have been images of gods or heroes.

In 1983 and 1985, two sets of plaster statues, all representing human figures, were excavated. The figures discovered 1985 were found by the driver of a bulldozers clearing the way for a road. Since plaster is fragile, the first set of statues was sent to the British Archaeological Institute, and the second set to the Smithsonian Institute, The whole 1985 site was unearthed and shipped to a Smithsonian laboratory where the figures it took ten years to assemble the figures. Conserved statues were returned to Jordan and can be seen in museums in Amman.

The strange anthropomorphic statues were found buried in pits in the vicinity of some special buildings that may have had ritual functions. These statues are half the size of of human. They have painted clothes, hair, and in some cases, ornamental tattoos or body paint. The eyes were created using plaster with a bitumen pupil and dioptase highlighting. Of the 32 plaster figures found, 15 of them are full figures, 15 are busts, and two are fragmentary heads. Three of the busts have were two heads. [Source: Wikipedia]

Both the full figures and busts were made by forming plaster over a skeleton made of bundles of reed wrapped in twine. Facial features were probably made by hand with simple tools made of bone, wood or stone. The plaster technology that was used was fairly advanced and required heating limestone to temperatures if 600̊ to 900̊C

Ba’ja Necklace

Ba'ja is a Neolithic village 14 kilometers (8.7 miles) north of Petra in southern Jordan. Like the nearby site of Basta, it was established around 7000 B.C. during the PPNB (Pre-Pottery Neolithic B) period.. The is located lies at an altitude of approximately 1,160 meters (3,810 feet), and is only accessible with a climbing route through a narrow, steep canyon. It is one of the largest neolithic villages in the Jordan area. [Source: Wikipedia]

Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology magazine: In 2018, archaeologists recovered more than 2,500 stone and shell beads from a child’s burial at the Neolithic village of Ba’ja. Most of the beads were found still in place on the neck and chest of an eight-year-old girl, who was interred in a fetal position 9,000 years ago. Although some beads had shifted due to the body’s placement, it was clear to archaeologist Hala Alarashi of the Spanish National Research Council that they had once been part of a magnificent necklace that fell apart as its connecting strings disintegrated. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology magazine, November/December 2023]

Based on the position of individual beads on the skeleton and repeating patterns of different bead types, Alarashi and her colleagues reconstructed the necklace. At the top, they connected strings of mostly red, black, and white beads to a hematite pendant found beneath the girl’s neck. At the bottom, they attached the strands to an engraved mother-of-pearl ring that was found on the body. Using geochemical analysis, the researchers also identified the materials that ancient artisans used to fashion the beads. Many were crafted from hematite, calcite, and mollusk shells, which were readily available in the area surrounding Ba’ja. A few, however, were made of more exotic materials, such as turquoise and amber, which the Ba’ja elite would have imported from far-flung locales throughout the Levant.

Sarah Kuta wrote in National Geographic History: Archaeologists have found other body ornaments in the ancient graves of children and adults at Ba’ja and other sites in the Near East, including in Syria and Turkey. But Alarashi says she’s never encountered one quite this elaborate or complex. The different types of beads — which are tubular, flat, or disc-shaped — are nearly identical in size and form, which suggests a highly skilled person or group used specialized tools to create them, she says. Some of the beads are made of locally available materials, while others would have come from far-flung locales like shells the Red Sea, some 60 miles to the south, and turquoise likely sourced from the Sinai Peninsula 150 miles away. And since the community of Ba’ja inhabited a remote and rugged site in the mountains near Petra, this raises questions about how and why the group would have sourced such materials, says Alarashi. [Source: Sarah Kuta, National Geographic History, August 25, 2023]

The beads present other puzzles, too. For instance, some appear to have been newly made at the time of the burial, while others were already well worn. “These differences mean something, but we don’t know what yet,” says Alarashi. “Who gave the used beads to this child? Maybe at the occasion of death, the elder of this child gave or participated in the creation of the necklace by giving their own old beads. Or maybe they gave the child the beads at birth.”

From the necklace and the complexity of the burial structure itself, archaeologists determined that the child — of undetermined sex — enjoyed high social status within their community. The burial was likely a “very important and emotional” moment for the group, one that may have also facilitated a period of reconciliation or negotiation between community members, says Alarashi. “These occasions of deep sorrow or moments of deep respect, that is the perfect time to resolve any tension or conflict,” she says. “We think the necklace and the burial played an additional role in this sense.”

Desert Kites

Neolithic hunters used “desert kites” to herd, trap and then kill prey. Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Desert kites consist of pairs of rock walls that extend across the landscape, often over several miles, and converge on an enclosure where prey such as gazelles could be herded and then easily dispatched. Ones in Jordan date to the Neolithic period (12,000 to 7,000 years ago). Reuters reported: “Although such structures can also be found elsewhere in the arid landscapes of the Middle East and south west Asia, these are believed to be the oldest, best preserved and the largest, the experts said. [Source: Suleiman Al-Khalidi and Hams Rabah, Reuters, February 23, 2022; Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, January/February 2023]

Desert kites are dry stone wall structures found in mainly in Southwest Asia (Middle East) but also in North Africa, Central Asia and Arabia. They were first discovered from the air during the 1920s. There are over 6,000 known ones, ranging in size from less than a hundred meters to several kilometres. They typically have a kite shape formed by two convergent "antennae" that run towards an enclosure, all formed by walls of dry stone less than one metre high, but variations exist. Research published in 2022 has shown that pits several metres deep often lie at the margins of enclosures, which have been interpreted as traps and killing pits. [Source: Wikipedia]

Similar structures have been in northern areas, notably under Lake Huron, and were used during the glacial peak of the last Ice Age to hunt reindeer. Recently one was found in the Baltic Sea. They have also been found in Greenland. Dating kites is difficult;various dating methods like radiocarbon dating and optically stimulated luminescence have yielded a wide range of dates. There are a handful of description in old travel reports. Some kites have later archaeological structures bult over them so if that structure can be dated we know at least the desert kite is at least older than the structure, and calculating erosion rates can provide a better date.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ARABIA AND MIDEAST FROM THE AIR: MUSTALIS, DESERT KITES AND FUNERARY AVENUES factsanddetails.com

9,000-YearNeolithic Hunting Shrine Located at a Desert Kite

In February 2022, the Jordan Minister of Tourism and Antiquities, announced the discovery of a 9,000-year-old shrine Jibal al-Khashabiyeh in the southeastern Badiya region in the Khashabiyeh Mountains in Jafr-Ma’an area near where hunter-gatherer community used stone traps to hunt deer and gazelles.

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: In the deserts of southeastern Jordan around 9,000 years ago, hunters erected a stone shrine that is one of the earliest ritual structures ever unearthed. A team led by archaeologists Mohammad Tarawneh of Al-Hussein Bin Talal University and Wael Abu-Azizeh of the French Institute of the Near East discovered the shrine in a Neolithic campsite near a network of “desert kites.” The team previously established that the kites near the shrine date to the Neolithic period and have now discovered clear evidence of the shrine’s connection to these enormous hunting installations. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, January/February 2023]

The shrine was built as a scale model of a kite, and one of two standing stelas found in the structure bears a stylized depiction of a desert kite. The team also unearthed a large stone altar with a number of incisions near a hearth. “One hypothesis is that the stone altar was used for butchering gazelle carcasses in the context of ritual activities carried out within the shrine,” says Abu-Azizeh. “The ritual performance most likely invoked supernatural forces for successful hunts.” A surprising cache of some 150 marine fossils was also found in the shrine, but the collection’s purpose remains unknown.

Reuters reported: “The team of French and Jordanian experts also found over 250 artifacts at the site, including exquisite animal figurines which they believe were used in rituals to invoke supernatural forces for successful hunts. The objects, which include two stone statues with carvings of human faces, are among some of the oldest artistic pieces ever found in the Middle East. "This is a unique site where large quantities of gazelles were hunted in complex rituals. It has no rival in the world from the stone age," said Wael Abu Azizeh, the co-director of the French archeological team. [Source: Suleiman Al-Khalidi and Hams Rabah, Reuters, February 23, 2022]

"They attest to the rise of extremely sophisticated mass hunting strategies, unexpected in such an early time frame," said a statement by the South Eastern Badia Archaeological Project (SEBAP) working on the site since 2013. “The settlement's circular hut-like dwellings and large quantities of gazelle remains show the inhabitants were not just hunting for their own needs but were also exchanging with neighbouring settlements.

Khatt Shebib and Big Circles

Heather Whipps amd Elizabeth Peterson wrote in Live Science: You might think that a 93-mile-long (150 kilometers) stone wall would have a very obvious purpose, but that is not the case for the Khatt Shebib. This mystery wall in Jordan was first reported in 1948, and archaeologists still aren't sure why it was built, when it was built or who built it. [Source: Heather Whipps, Elizabeth Peterson, Live Science, October 27, 2016]

The wall runs north-northeast to south-southwest and contains sections where two walls run side by side, as well as sections where the wall branches off. Though today the wall is in ruins, in its heyday, most of it would have stood about 3.3 feet (1 meter) high and just 1.6 feet (0.5 meters) wide; it's unlikely that the Khatt Shebib was built to keep out invading armies. However, it may have been constructed to keep out less threatening enemies — like hungry goats, for example. Traces of ancient agriculture to the west of the wall suggest that the structure may have served as a boundary between ancient farmlands and the pastures of nomadic farmers, according to archaeologists with the Aerial Archaeology in Jordan project. [See Photos of the Mysterious Ancient Wall in Jordan]

The Khatt Shebib isn't the only ancient structure in Jordan that has archaeologists puzzled; Stone circles, dating back 2,000 years and dotting the Jordanian countryside, also have scientists scratching their heads. Known simply as the "Big Circles," 11 of these structures have been spotted so far in Jordan. The circles are about 1,312 feet (400 m) in diameter and are just a few feet high. None of these short-walled circles have openings for people or animals to walk through, so it's unlikely that they are ancient examples of livestock corrals, according to archaeologists. So what exactly were they for? No one knows. Researchers are now comparing the Big Circles with other circular stone structures in the Middle East to figure out their mysterious purpose.

According to Archaeology magazine: “Researchers from the Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East have brought renewed attention to an archaeological phenomenon known as “Big Circles.” Spread across parts of Jordan and Syria, these manmade features have received very little archaeological attention and are relatively unknown, even to regional experts. They are thought to be at least 2,000 years old — two of them are cut by later Roman roads — but may date as far back as the Neolithic. Constructed of stone walls rarely rising more than a few feet, they measure about 1,300 feet in diameter, and, puzzlingly, show no evidence of entrances. “The combination of aerial recording of each circle, sites with which it may intersect, its context, and examination on the ground, have helped clarify their character and possible date,” says project director David Kennedy. The origin, function, and purpose of the circles remain a mystery, although Kennedy hopes that his work will provide a new perspective from which to analyze them. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2015]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and "Atlas of Jordan" except the map Researchgate, necklace and from Alarashi, Plos One

Text Sources: Live Science, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. The Independent, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024