Home | Category: Education, Transportation and Health

EDUCATION IN MESOPOTAMIA

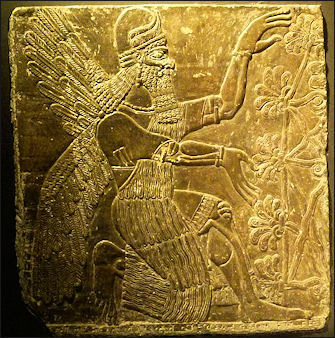

Winged Genius Assistant Few people in Mesopotamia could read or write. Schooling was provided at temples or academies or at the homes of priests and bureaucrats. Students studied languages, arithmetic, accounting and Sumerian literature. Textbooks were cuneiform tablets.

Most students were future scribes who were taught to write on cuneiform tablets at academies and temple schools. A series of benches excavated at Mari are believed to be from an ancient classroom. Many lessons consisted of teachers writing on one side of a tablet and students writing on the other side or students copying books. Many tablets that have come down to us today are student copies of early chapters (most didn’t get very far because few later chapters exist).

Instructors were men. Part of the boy's education, we are informed, consisted in his being taught to shoot with the bow and to practise other bodily exercises. But the larger part of his time was given to learning how to read and write. The acquisition of the cuneiform system of writing was a task of labor and difficulty which demanded years of patient application. A vast number of characters had to be learned by heart. They were conventional signs, often differing but slightly from one another, with nothing about them that could assist the memory; moreover, their forms varied in different styles of writing, as much as Latin, Gothic, and cursive forms of type differ among ourselves, and all these the pupil was expected to know. Every character had more than one phonetic value; many of them, indeed, had several, while they could also be used ideographically to express objects and ideas. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Commentaries, moreover, had been written upon the works of ancient authors, in which difficult or obsolete terms were explained. The pupils were trained to write exercises, either from a copy placed before them or from memory. These exercises served a double purpose — they taught the pupil how to write and spell, as well as the subject which the exercise illustrated. A list of the kings of the dynasty to which Hammurabi belonged has come to us, for instance, in one of them. In this way history and geography were impressed upon the student's memory, together with extracts from the poets and prosewriters of the past.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Back to School in Babylonia” by Susanne Paulus, Marta Diaz Herrera, et al. (2023) Amazon.com;

“Old Babylonian Texts in the Schøyen Collection, Part Two: School Letters, Model Contracts, and Related Texts” by A. R. George and Gabriella Spada (2019) Amazon.com;

“Learning to Pray in a Dead Language: Education and Invocation in Ancient Sumerian”

by Joshua Bowen and Megan Lewis )2020) Amazon.com;

“The Library of Ancient Wisdom: Mesopotamia and the Making of History” by Laura Selena Wisnom (2025) Amazon.com;

“Sin and Sanction in Israel and Mesopotamia: A Comparative Study” by K Van Der Toorn (1985) Amazon.com;

“Wisdom Literature in Mesopotamia and Israel” (Society of Biblical Literature Symposium) by Richard J. Clifford (2007) Amazon.com;

“Mathematics in Ancient Iraq: A Social History” by Eleanor Robson (2008) Amazon.com;

“Alphabet Scribes in the Land of Cuneiform: Sēpiru Professionals in Mesopotamia in the Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid Period” by Yigal Bloch (2018) Amazon.com;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East” by Amanda H Podany (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Knowledge Networks: A Social Geography of Cuneiform Scholarship in First-Millennium Assyria and Babylonia” by Eleanor Robson (2019) Amazon.com;

“Scholars and Scholarship in Late Babylonian Uruk” by Proust, Christine Proust, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“Philosophy Before the Greeks: The Pursuit of Truth in Ancient Babylonia” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2015) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

Scribes in Mesopotamia

One of the highest positions in Mesopotamia society was the scribe, who worked closely with the king and the bureaucracy, recording events and tallying up commodities. The kings were usually illiterate and they were dependent on the scribes to make their wishes known to their subjects. Learning and education was primarily the provenance of scribes.

In ancient Mesopotamia writing — and also reading — was a professional rather than a general skill. Being a scribe was an honorable profession. Professional scribes prepared a wide range of documents, oversaw administrative matters and performed other essential duties.Some scribes could write very fast. One Sumerian proverb went: "A scribe whose hands move as fast the mouth, that's a scribe for you."

Scribes were the only formally educated members of society. They were trained in the arts, mathematics, accounting and science. They were employed mainly at palaces and temples where their duties included writing letters, recording sales of land and slaves, drawing up contracts, making inventories and conducting surveys. Some scribes were women.

See Separate Article: CUNEIFORM (MESOPOTAMIAN WRITING): DEVELOPMENT, SCRIBES, PRODUCTION, SUBJECTS africame.factsanddetails.com

Schools in Ancient Mesopotamia

The school must have been attached to the library, and was probably an adjacent building. This will explain the existence of the school-exercises which have come from the library of Nineveh, as well as the readingbooks and other scholastic literature which were stored within it. At the same time, when we remember the din of an oriental school, where the pupils shout their lessons at the top of their voices, it is impossible to suppose that the scribes and readers would have been within ear-shot. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Nor was it probable that there was only one school in a town of any size. The practice of herding large numbers of boys or girls together in a single school-house is European rather than Asiatic. The school in later times developed into a university. At Borsippa, the suburb of Babylon, where the library had been established in the temple of Nebo, we learn from Strabo that a university also existed which had attained great celebrity. From a fragment of a Babylonian medical work, now in the British Museum, we may perhaps infer that it was chiefly celebrated as a school of medicine.

In Assyria education was mainly confined to the upper classes. The trading classes were perforce obliged to learn how to read and write; so also were the officials and all those who looked forward to a career in the diplomatic service. But learning was regarded as peculiarly the profession of the scribes, who constituted a special class and occupied an important position in the bureaucracy.

Education for Girls in Mesopotamia

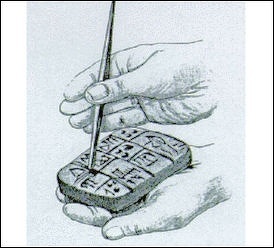

writing cuneiform

One of the texts which, in Sumerian days, was written as a head-line in his copy-book declared that “He who would excel in the school of the scribes must rise like the dawn.” Girls also shared in the education given to their brothers. Among the Babylonian letters that have been preserved are some from ladies, and the very fact that women could transact business on their own account implies that they could read and write. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Thus the following letter, written from Babylon by a lover to his mistress at Sippara, assumes that she could read it and return an answer: “To the lady Kasbeya thus says Gimil-Marduk: May the Sun-god and Marduk, for my sake, grant thee everlasting life! I am writing to enquire after your health; please send me news of it. I am living at Babylon, but have not seen you, which troubles me greatly. Send me news of your arrival, so that I may be happy. Come in the month Marchesvan. May you live forever, for my sake!”

The Tel-el-Amarna collection actually contains letters from a lady to the Egyptian Pharaoh. One of them is as follows: “To the king my lord, my gods, my sun-god, thus says Nin, thy handmaid: At the feet of the king my lord, my gods, my sun-god, seven times seven I prostrate myself. The king my lord knows that there is war in the land, and that all the country of the king my lord has revolted to the Bedouin. But the king my lord has knowledge of his country, and the king my lord knows that the Bedouin have sent to the city of Ajalon and to the city of Zorah, and have made mischief (and have intrigued with) the two sons of Malchiel; and let the king my lord take knowledge of this fact.” The oracles delivered to Esar-haddon by the prophetesses of Arbela are in writing, and we have no grounds for thinking that they were written down by an uninspired pen.

Indeed, the “bit riduti,” or “place of education,” where Assur-bani-pal tells us he had been brought up, was the woman's part of the palace.The instructors, however, were men, and part of the boy's education, we are informed, consisted in his being taught to shoot with the bow and to practise other bodily exercises.

Language Learning in Ancient Mesopotamia

Education, as we have seen, meant a good deal more than merely learning the cuneiform characters. It meant, in the case of the Semitic Babylonians and Assyrians, learning the ancient agglutinative language of Sumer as well. A knowledge of the cuneiform syllabary necessitated also a knowledge of the language of the Sumerians, who had been its inventors, and it frequently happened that a group of characters which had expressed a Sumerian word was retained in the later script with the pronunciation of the corresponding Semitic word attached to them, though the latter had nothing to do with the phonetic values of the several signs, whether pronounced singly or as a whole. The children, however, must have been well taught. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

This is clear from the remarkably good spelling which we find in the private letters; it is seldom that words are misspelt. The language may be conversational, or even dialectic, but the words are written correctly. The school-books that have survived bear testimony to the attention that had been given to improving the educational system. Every means was adopted for lessening the labor of the student and imprinting the lesson upon his mind. The cuneiform characters had been classified and named; they had also been arranged according to the number and position of the separate wedges of which they consisted.

Dictionaries had been compiled of Sumerian words and expressions, as well as lists of Semitic synonyms. Even grammars had been drawn up, in which the grammatical forms of the old language of Sumer were interpreted in Semitic Babylonian. There were reading-books filled with extracts from the standard literature of the country. Most of this was in Sumerian; but the Sumerian text was provided with a Semitic translation, sometimes interlinear, sometimes in a parallel column.

In later times Sumerian ceased to be spoken except in learned society, and consequently bore the same relation to Semitic Babylonian that Latin bears to English. In learning Sumerian, therefore, the Babylonian learned what was equivalent to Latin in the modern world. And the mode of teaching it was much the same. There were the same paradigms to be committed to memory, the same lists of words and phrases to be learned by heart, the same extracts from the authors of the past to be stored up in the mind. Even the “Hamiltonian” system of learning a dead language had already been invented.

Exercise Tablets In Ancient Mesopotamian Schools

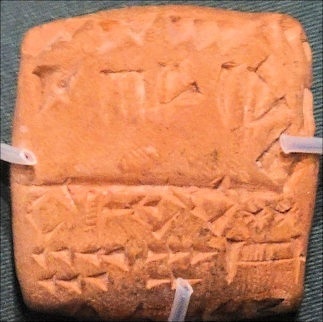

math exam: calculating the area of a square, knowing one side

Many tablets are left half completed. Other have mistakes that have been rubbed out or have disapproving tick marks added by teachers. There are indications of unsteady hand, lack of patience, and trouble learning. Scribes that passed the examinations at the scribe academy were given the title "The one who knows the tablets." Some tablets also featured aimless doodling in what seems to be a manifestation of daydreaming.

Katy Blanchard of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology told the New York Times in a Babylonian classroom, “there would be a bucket in the middle of the room” where students would toss their practice tablets for recycling. Those reusable tablets, she said, were “like the original Etch A Sketch.” [Source: Jennifer A. Kingson, New York Times November 14, 2016]

A selection from a paternal essay went: "Why do you idle about? Go to school, stand before your 'school-father,' recite your assignment, open your schoolbag, write your tablet, let your 'big brother' write your new tablet for you. After you have finished your assignment and reported to your monitor, come to me."

It continued: "Don't stand about in the public square or wander about the boulevard. When walking on the street, don't look all around...Go to school, it will be of benefit to you...I, night and day am I tortured because of you. Night and day you waste in pleasures.”

Lessons in Sumerian Math

As well as providing a medium for the first writing, cuneiform clay tablet were the first recording medium to be used in education. Nicholas Wade wrote in the New York Times: Many of the 13 tablets at a 2010 exhibition at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, part of New York University, were “exercises of students learning to be scribes. Their plight was not to be envied. They were mastering mathematics based on texts in Sumerian, a language that even at the time was long since dead. The students spoke Akkadian, a Semitic language unrelated to Sumerian. But both languages were written in cuneiform, meaning wedge-shaped, after the shape of the marks made by punching a reed into clay. [Source: Nicholas Wade, New York Times, November 22, 2010 ^=^]

“They include two celebrated tablets, known as YBC 7289 and Plimpton 322, that have played central roles in the reconstruction of Babylonian math. YBC 7289 is a small clay disc containing a rough sketch of a square and its diagonals. Across one of the diagonals is scrawled 1,24,51,10 — a sexagesimal number that corresponds to the decimal number 1.41421296. Yes, you recognized it at once — the square root of 2. In fact it’s an approximation, a very good one, to the true value, 1.41421356.^=^

“Below is its reciprocal, the answer to the problem, that of calculating the diagonal of a square whose sides are 0.5 units. This bears on the issue of whether the Babylonians had discovered Pythagoras’s theorem some 1,300 years before Pythagoras did. No tablet bears the well-known algebraic equation, that the squares of the two smaller sides of a right-angled triangle equal the square of the hypotenuse. But Plimpton 322 contains columns of numbers that seem to have been used in calculating Pythagorean triples, sets of numbers that correspond to the sides and hypotenuse of a right triangle, like 3, 4 and 5. ^=^

“Plimpton 322 is thought to have been written in Larsa, just north of Ur, some 60 years before the city was captured by Hammurabi the lawgiver in 1762 B.C. Other tablets bear lists of practical problems, like calculating the width of a canal, given information about its other dimensions, the cost of digging it and a worker’s daily wage. With some tablets the answers are stated without any explanation, giving the impression that they were for show, a possession designed to make the owner seem an academic.” ^=^

Study of History, Law and Unusual Phenomena in Ancient Mesopotamia

History, too, was a favorite subject of study. Like the Hebrews, the Assyrians were distinguished by a keen historical sense which stands in curious contrast to the want of it which characterized the Egyptian. The Babylonians also were distinguished by the same quality, though perhaps to a less extent than their Assyrian neighbors, whose somewhat pedantic accuracy led them to state the exact numbers of the slain and captive in every small skirmish, and the name of every petty prince with whom they came into contact, and who had invented a system of accurately registering dates at a very early period. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Nevertheless, the Babylonian was also a historian; the necessities of trade had obliged him to date his deeds and contracts from the earliest age of his history, and to compile lists of kings and dynasties for reference in case of a disputed title to property. The historical honesty to which he had been trained is illustrated by the author of the Babylonian Chronicle in the passage relating to the battle of Khalulê, which has been already alluded to. The last king of Babylonia was himself an antiquarian, and had a passion for excavating and discovering the records of the monarchs who had built the great temples of Chaldea.

Law, again, must have been much studied, and so, too, was theology. The library of Nineveh, however, from which so much of our information has come, gives us an exaggerated idea of the extent to which the pseudo-science of omens and portents was cultivated. Its royal patron was a believer in them, and apparently more interested in the subject than in any other. Consequently, the number of books relating to it are out of all proportion to the rest of the literature in the library. But this was an accident, due to the predilections of Assur-bani-pal himself. The study of omens and portents was a branch of science and not of theology, false though the science was. But it was based upon the scientific principle that every antecedent has a consequent, its fallacy consisting in a confusion between real causes and mere antecedents.

Certain events had been observed to follow certain phenomena; it was accordingly assumed that they were the results of the phenomena, and that were the phenomena to happen again they would be followed by the same results. Hence all extraordinary or unusual occurrences were carefully noted, together with whatever had been observed to come after them. A strange dog, for instance, had been observed to enter a palace and there lie down on a couch; as no disaster took place subsequently it was believed that if the occurrence was repeated it would be an omen of good fortune. On the other hand, the fall of a house had been preceded by the birth of a child without a mouth; the same result, it was supposed, would again accompany the same presage of evil. These pseudoscientific observations had been commenced at a very early period of Babylonian history, and were embodied in a great work which was compiled for the library of Sargon of Akkad.

Study of Science, Astrology and Astronomy in Ancient Mesopotamia

One library contained a 72-book volume on astrology called “The Illumination of Bel.” But in this case the observations were not wholly useless. The study of astrology was intermixed with that of astronomy, of which Babylonia may be considered to be the birthplace. The heavens had been mapped out and the stars named; the sun's course along the ecliptic had been divided into the twelve zodiacal signs, and a fairly accurate calendar had been constructed. Hundreds of observations had been made of the eclipses of the sun and moon, and the laws regulating them had been so far ascertained that, first, eclipses of the moon, and then, but with a greater element of uncertainty, eclipses of the sun, were able to be predicted. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

One of the chapters or books in the “Illumination of Bel” was devoted to an account of comets, another dealt with conjunctions of the sun and moon. There were also tables of observations relating to the synodic revolution of the moon and the synodic periods of the planet Venus. The year was divided into twelve months of thirty days each, an intercalary month being inserted from time to time to rectify the resulting error in the length of the year. The months had been originally called after the signs of the zodiac, whose names have come down to ourselves with comparatively little change. But by the side of the lunar year the Babylonians also used a sidereal year, the star Capella being taken as a fixed point in the sky, from which the distance of the sun could be measured at the beginning of the year, the moon being used as a mere pointer for the purpose.

At a later date, however, this mode of determining time was abandoned, and the new year was made directly dependent on the vernal equinox. The month was subdivided into weeks of seven days, each of which was consecrated to a particular deity. These deities were further identified with the stars. The fact that the sun and moon, as well as the evening and morning stars, were already worshipped as divinities doubtless led the way to this system of astrotheology. But it seems never to have spread beyond the learned classes and to have remained to the last an artificial system. The mass of the people worshipped the stars as a whole, but it was only as a whole and not individually. Their identification with the gods of the state religion might be taught in the schools and universities, but it had no meaning for the nation at large.

Ancient Mesopotamian Scholarship

Exercises were set in translation from Sumerian into Babylonian, and from Babylonian into Sumerian, and the specimens of the latter which have survived to us show that “dog-Latin” was not unknown. But the dead language of Sumer was not all that the educated Babylonian or Assyrian gentlemen of later times was called upon to know. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Here, then, we have an Assyrian officer who is acquainted not only with Sumerian, but also with two of the living languages of Western Asia. And yet he was not a scribe; he did not belong to the professional class of learned men. Nothing can show more clearly the advanced state of education even in the military kingdom of Assyria. In Babylonia learning had always been honored; from the days of Sargon of Akkad onward the sons of the reigning king did not disdain to be secretaries and librarians. The linguistic training undergone in the schools gave the Babylonian a taste for philology. He not only compiled vocabularies of the extinct Sumerian, which were needed for practical reasons, he also explained the meaning of the names of the foreign kings who had reigned over Babylonia, and from time to time noted the signification of words belonging to the various languages by which he was surrounded.

Thus one of the tablets we possess contains a list of Kassite or Kossean words with their signification; in other cases we have Mitannian, Elamite, and Canaanite words quoted, with their meanings attached to them. Nor did the philological curiosity of the scribe end here. He busied himself with the etymology of the words in his own language, and just as a couple of centuries ago our own dictionary-makers endeavored to find derivations for all English words, whatever their source, in Latin and Greek, so, too, the Babylonian etymologist believed that the venerable language of Sumer was the key to the origin of his own. Many of the words in Semitic Babylonian were indeed derived from it, and accordingly Sumerian etymologies were found for other words which were purely Semitic. The word Sabattu, “the Sabbath,” for instance, was derived from the Sumerian Sa, “heart,” and bat, “to cease,” and so interpreted to mean the day on which “the heart ceased” from its labors.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024