Home | Category: Languages and Writing / Literature

CUNEIFORM

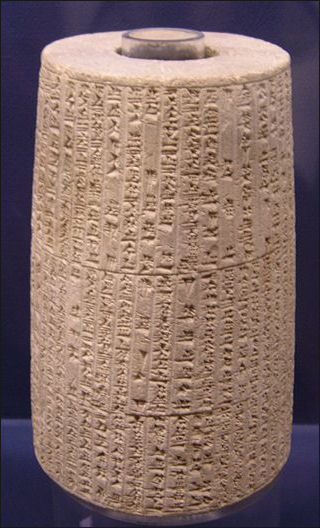

Nebuchadnezzar Barrel cylinder Cuneiform, the script language of ancient Sumer and Mesopotamia, consists of small, repetitive impressed characters that look more like wedge-shape footprints than what we recognize as writing. Cuneiform (Latin for "wedge shaped") appears on baked clay or mud tablets that range in color from bone white to chocolate to charcoal. Inscriptions were also made on pots and bricks. Each cuneiform sign consists of one or more wedge-shaped impressions that are made with three basic marks: a triangle, a line or curbed lines made with dashes.

Cuneiform (pronounced “cune-AY-uh-form”) was devised by the Sumerians more than 5,200 years ago and remained in use until about A.D. 80 A.D. when it was replaced by the Aramaic alphabet Jennifer A. Kingson wrote in the New York Times: "Evolving roughly at the same time as early Egyptian writing, it served as the written form of ancient tongues like Akkadian and Sumerian. Because cuneiform was written in clay (rather than on paper on papyrus) and important texts were baked for posterity, a large number of readable tablets have survived to modern times. Many of them written by professional scribes who used a reed stylus to etch pictograms into clay. [Source: Jennifer A. Kingson, New York Times November 14, 2016]

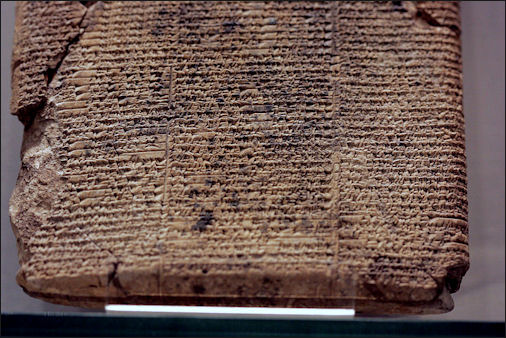

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: Ancient Mesopotamian literature commonly refers to the vast — and as yet far from complete — body of writings in cuneiform script which has come down from Ancient Mesopotamia. It is mostly found on clay tablets on which the writing was impressed when the clay was still moist. The writing reads, as does the writing on a printed English page, from left to right on the line, the lines running from the top of the page downwards. There are indications, however, that cuneiform writing once read from top to bottom and then, column for column, from right to left. The tablets when inscribed were usually allowed to dry naturally, occasionally, if durability was of the essence, they were baked at a high temperature to hard ceramic.[Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

Cuneiform was used by speakers of 15 languages over 3,000 years. The Sumerians, Babylonians and Eblaites had large libraries of clay tablets. The Elbaites wrote in columns and used both sides of the tablets. The latest datable tablet, from Babylon, described the planetary positions for A.D. 74-75.

The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology has one of the world’s largest collections of cuneiform tablets from early Mesopotamia. Yale also has a bunch, including a tablets of meal recipes.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture” by Karen Radner and Eleanor Robson (2020) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History” by Marc Van De Mieroop (1999) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform” by Irving Finkel (2015) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform” by C. B. F. Walker (1987) Amazon.com;

“A New Workbook of Cuneiform Signs” by Daniel C Snell (2022) Amazon.com;

“Supplement to a New Workbook of Cuneiform Signs: Teaching Old Akkadian and Old Babylonian Sign Forms” by Daniel C Snell (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Archæology of the Cuneiform Inscriptions” by Archibald Henry Sayce (1906) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform Texts from Various Collections” by Albrecht Goetze Amazon.com;

“The Amarna Scholarly Tablets” by Shlomo Izre'el (1997) Cuneiform Tablets in Egypt Amazon.com;

“Digital Cuneiform” by Johannes Bergerhausen (2014) Amazon.com;

Writing on Clay in Mesopotamia

A shortage of stone and the abundance of clay had another and unique influence upon Babylonian culture. It led to the invention of the written clay tablet, which has had such momentous results for the civilization of the whole Eastern world. The pictures with which Babylonian writing began were soon discarded for the conventional forms, which could so easily be impressed by the stylus upon the soft clay. It is probable that the use of the clay as a writing material was first suggested by the need there was in matters of business that the contracting parties should record their names. The absence of stone made every pebble valuable, and pebbles were accordingly cut into cylindrical forms and engraved with signs. When the cylinder was rolled over a lump of wet clay, its impress remained forever. The signs became cuneiform characters, and the Babylonian wrote them upon clay instead of stone. The seal-cylinder and the use of clay as a writing material must consequently be traced to the peculiar character of the country in which the Babylonian lived. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Papyrus, it is true, was occasionally used, but it was expensive, while clay literally lay under the feet of everyone. While the clay was still soft, the cuneiform or “wedge-shaped” characters were engraved upon it by means of a stylus. They had originally been pictorial, but when the use of clay was adopted the pictures necessarily degenerated into groups of wedge-like lines, every curve becoming an angle formed by the junction of two lines. As time went on, the characters were more and more simplified, the number of wedges of which they consisted being reduced and only so many left as served to distinguish one sign from another. The simplification reached its extreme point in the official script of Assyria. At first the clay tablet after being inscribed was allowed to dry in the sun.

But sun-dried clay easily crumbles, and the fashion accordingly grew up of baking the tablet in a kiln. In Assyria, where the heat of the sun was not so great as in the southern kingdom of Babylonia, the tablet was invariably baked, holes being first drilled in it to allow the escape of the moisture and to prevent it from cracking. Some of the early Babylonian tablets were of great size, and it is wonderful that they have lasted to our own days. But the larger the tablet, the more difficult it was to bake it safely, and consequently the most of the tablets are of small size. As it was often necessary to compress a long text into this limited space, the writing became more and more minute, and in many cases a magnifying glass is needed to read it properly. That such glasses were really used by the Assyrians is proved by Layard's discovery of a magnifying lens at Nineveh. The lens, which is of crystal, has been turned on a lathe, and is now in the British Museum. But even with the help of lenses, the study of the cuneiform tablets encouraged short sight, which must have been common in the Babylonian schools. In the case of Assur-bani-pal this was counteracted by the out-of-door exercises in which he was trained, and it is probable that similar exercises were also customary in Babylonia.

Sumerian Writing

Clay tablets with pictographs appeared around 4000 B.C. The earliest with Sumerian writing appeared around 3200 B.C. Around 2,500 B.C., Sumerian writing evolved into partial syllabic script capable of recording the vernacular. A Sumerian clay tablet from around 3200 B.C. inscribed in wedgelike cuneiform with a list of professions “is among the earliest examples of writings that we know of so far,” according to the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute’ director, Gil J. Stein. [Source: Geraldine Fabrikant. New York Times, October 19, 2010] The Sumerian are credited with inventing writing around 3200 B.C. based on symbols that showed up perhaps around 8,000 B.C. What distinguished their markings from pictograms is that theye were symbols representing sounds and abstract concepts instead of images. No one knows who the genius was who came up with this idea. The exact date of early Sumerian writing is difficult to ascertain because the methods of dating tablets, pots and bricks on which the oldest tablets with writing were found are not reliable.

By around 3200 B.C., the Sumerians had developed an elaborate system of pictograph symbols with over 2,000 different signs. A cow, for example, was represented with a stylized picture of a cow. But sometimes it was accompanied by other symbols. A cow symbols with three dots, for example, meant three cows.

By around 3100 B.C., these pictographs began representing sounds and abstract concepts. A stylized arrow, for example, was used to represent the word "ti" (arrow) as well as the sound "ti," which would have been difficult to depict otherwise. This meant individual signs could represent both words and syllables within a word.

The first clay tablets with Sumerian writing were found in the ruins of the ancient city of Uruk. It is no known what the said. They appear to have been list of rations of foods. The shapes appear to have been based on objects they represent but there is no effort to be naturalistic portrayals The marks are simple diagrams. So far over a half a million tablets and writing boards with cuneiform writing have been discovered.

John Alan Halloran of sumerian.org wrote: “When the Sumerians invented their writing system around 5400 years ago, it was a pictographic and ideographic system like the Chinese...Yes. Some of the Sumerian ideograms gradually became used as syllabograms, which included the vowel indications. Writing on clay was an inexpensive yet permanent way of recording transactions. The cultural influence of the Sumerians upon later Mesopotamian peoples was enormous. Cuneiform writing has been found at Amarna in Egypt, in the form of an alphabet at Ugarit, and among the Hittites who used it to render their own Indo-European language.” [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org]

Book: “A Manual of Sumerian Grammar and Texts,” by John L. Hayes is a good introduction to Sumerian writing.

Evolution of the Earliest Sumerian Writing

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: The earliest evidence of writing from Mesopotamia — or indeed from anywhere — dates back to around the middle of the fourth millennium B.C. to the period known variously as the Protoliterate period or Uruk iv. Before this, however, literature doubtlessly existed in Mesopotamia in oral form, and as such it probably continued alongside written literature for long spans of time. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com =]

The uses of writing were from the beginning those of aiding memory and of organizing complex data, as is well illustrated by the two genres that comprise the earliest written materials: sign lists and accounts. In time, new genres evolved from these genres: lexical texts, derived from sign lists; contracts and boundary stones, derived from accounts of gifts that accompanied a legal agreement to serve as a testimony to it; and, as a new departure, monumental inscriptions: votive and building inscriptions; and the letter, originally, as shown by its form, an aide-mémoire for the messenger delivering it as an oral message. =

Ira Spar of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Some of the earliest signs inscribed on the tablets picture rations that needed to be counted, such as grain, fish, and various types of animals. These pictographs could be read in any number of languages much as international road signs can easily be interpreted by drivers from many nations. Personal names, titles of officials, verbal elements, and abstract ideas were difficult to interpret when written with pictorial or abstract signs. [Source: Spar, Ira. "The Origins of Writing", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004 metmuseum.org \^/]

“A major advance was made when a sign no longer just represented its intended meaning, but also a sound or group of sounds. To use a modern example, a picture of an "eye" could represent both an "eye" and the pronoun "I." An image of a tin can indicates both an object and the concept "can," that is, the ability to accomplish a goal. A drawing of a reed can represent both a plant and the verbal element "read." When taken together, the statement "I can read" can be indicated by picture writing in which each picture represents a sound or another word different from an object with the same or similar sound. \^/

“This new way of interpreting signs is called the rebus principle. Only a few examples of its use exist in the earliest stages of cuneiform from between 3200 and 3000 B.C. The consistent use of this type of phonetic writing only becomes apparent after 2600 B.C. It constitutes the beginning of a true writing system characterized by a complex combination of word-signs and phonograms—signs for vowels and syllables—that allowed the scribe to express ideas. By the middle of the third millennium B.C., cuneiform primarily written on clay tablets was used for a vast array of economic, religious, political, literary, and scholarly documents.” \^/

The use of writing as a means to organize and remember data underlies such genres as date lists and king lists. However, it is quite late that this power to organize complex data is fully utilized, with the creation of canonical series and handbooks, a development which begins in Old Babylonian Times and culminates in the Kassite period around the middle of the second millennium B.C. =

Scribes in Ancient Mesopotamia

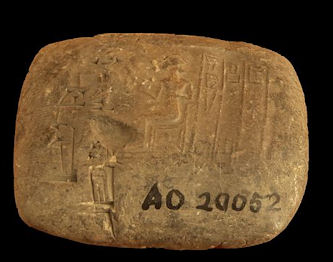

daily salary in Ur One of the highest positions in Mesopotamia society was the scribe, who worked closely with the king and the bureaucracy, recording events and tallying up commodities. The kings were usually illiterate and they were dependent on the scribes to make their wishes known to their subjects. Learning and education was primarily the provenance of scribes.

In ancient Mesopotamia writing — and also reading — was a professional rather than a general skill. Being a scribe was an honorable profession. Professional scribes prepared a wide range of documents, oversaw administrative matters and performed other essential duties.Some scribes could write very fast. One Sumerian proverb went: "A scribe whose hands move as fast the mouth, that's a scribe for you."

Scribes were the only formally educated members of society. They were trained in the arts, mathematics, accounting and science. They were employed mainly at palaces and temples where their duties included writing letters, recording sales of land and slaves, drawing up contracts, making inventories and conducting surveys. Some scribes were women.

High Position of Scribes in Ancient Mesopotamia

In ancient Mesopotamia scribes constituted a special class and occupied an important position in the bureaucracy. They acted as clerks and secretaries in the various departments of state, and stereotyped a particular form of cuneiform script, which we may call the chancellor's hand, and which, through their influence, was used throughout the country. In Babylonia it was otherwise. Here a knowledge of writing was far more widely spread, and one of the results was that varieties of handwriting became as numerous as they are in the modern world. The absence of a professional class of scribes prevented any one official hand from becoming universal. We find even the son of an “irrigator,” one of the poorest and lowest members of the community, copying a portion of the “Epic of the Creation,” and depositing it in the library of Borsippa for the good of his soul. Indeed, the contract tablets show that the slaves themselves could often read and write. The literary tendencies of Assur-bani-pal doubtless did much toward the spread of education in Assyria, but the latter years of his life were troubled by disastrous wars, and the Assyrian empire and kingdom came to an end soon after his death. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The scribes were a large and powerful body, and in Assyria, where education was less widely diffused than in Babylonia, they formed a considerable part of the governing bureaucracy. In Babylonia they acted as librarians, authors, and publishers, multiplying copies of older books and adding to them new works of their own. They served also as clerks and secretaries; they drew up documents of state as well as legal contracts and deeds. They were accordingly responsible for the forms of legal procedure, and so to some extent occupied the place of the barristers and attorneys of to-day. The Babylonian seems usually, if not always, to have pleaded his own case; but his statement of it was thrown into shape by the scribe or clerk like the final decision of the judges themselves. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Under Nebuchadnezzar and his successors such clerks were called “the scribes of the king,” and were probably paid out of the public revenues. Thus in the second year of Evil-Marduk it is said of the claimants to an inheritance that “they shall speak to the scribes of the king and seal the deed,” and the seller of some land has to take the deed of quittance “to the scribes of the king,” who “shall supervise and seal it in the city.” Many of the scribes were priests; and it is not uncommon to find the clerk who draws up a contract and appears as a witness to be described as “the priest” of some deity.

Production of Cuneiform Tablets

According to Archaeology magazine: “First developed around 3200 B.C. by Sumerian scribes in the ancient city-state of Uruk, in present-day Iraq, as a means of recording transactions, cuneiform writing was created by using a reed stylus to make wedge-shaped indentations in clay tablets. Later scribes would chisel cuneiform into a variety of stone objects as well. Different combinations of these marks represented syllables, which could in turn be put together to form words. Cuneiform as a robust writing tradition endured 3,000 years. The script — not itself a language — was used by scribes of multiple cultures over that time to write a number of languages other than Sumerian, most notably Akkadian, a Semitic language that was the lingua franca of the Assyrian and Babylonian Empires. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

Cuneiform symbols were made by scribes who used a stylus — with a triangular tip cut from reed — to make impressions on damp clay. The reeds could make straight lines and triangles but could not easily make curved lines. Different characters were made by superimposing identical triangles in different combinations. Complex characters had around 13 triangles. The moistened tablets were left to dry in the hot sun. After archaeologists excavate the tablets they are carefully cleaned and baked for preservation. The process is expensive and slow.

Many cuneiform tablets are dated by the year, month and day. Tablets from monarchs, ministers and other important people were impressed with their seal, which was applied on the wet clay like a paint roller with a cylinder seal. Some cylinder seals produced reliefs that were quite elaborate, made up of scores of images and markings. Important messages were encased in an "envelope" of more clay to insure privacy.

Contents of Cuneiform Tablets

Most of the early writing was used to make lists of commodities. The writing system is believed to have developed in response to an increasingly complex society in which records needed to be kept on taxes, rations, agricultural products and tributes to keep society running smoothly. The oldest examples of Sumerian writing were bills of sales that recorded transactions between a buyer and seller. When a trader sold ten head of cattle he included a clay tablet that had a symbol for the number ten and a pictograph symbol of cattle.

The Mesopotamians could also be described as the worlds first great accountants. The recorded everything that was consumed in the temples on clay tablets and placed them in the temple archives. Many of the tablets recovered were lists of items like this. They also listed "errors and phenomena" that seemed to result in divine retribution such as sickness or bad weather.

Cuneiform writing began mainly as a means of keeping records but developed into a full blown written language that produced great works of literature such as the Gilgamesh story. By 2500 B.C. Sumerian scribes could write almost anything with 800 or so cuneiform signs, including myths, fables, essays, hymns, proverbs, epic poetry, lamentations, laws, lists of astronomical events, list of plants and animals, medical texts with lists ailments and their herbal . There are tablets that record intimate correspondence between friends.

Subjects of Cuneiform Tablets

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: In early 2016, hundreds of media outlets around the world reported that a set of recently deciphered ancient clay tablets revealed that Babylonian astronomers were more sophisticated than previously believed. This implicitly challenged the perception that cuneiform tablets were used merely for basic accounting, such as tallying grain, rather than for complex astronomical calculations. While most tablets were, in fact, used for mundane bookkeeping or scribal exercises, some of them bear inscriptions that offer unexpected insights into the minute details of and momentous events in the lives of ancient Mesopotamians. [Source:Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: In early 2016, hundreds of media outlets around the world reported that a set of recently deciphered ancient clay tablets revealed that Babylonian astronomers were more sophisticated than previously believed. This implicitly challenged the perception that cuneiform tablets were used merely for basic accounting, such as tallying grain, rather than for complex astronomical calculations. While most tablets were, in fact, used for mundane bookkeeping or scribal exercises, some of them bear inscriptions that offer unexpected insights into the minute details of and momentous events in the lives of ancient Mesopotamians. [Source:Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

One of the most famous Sumerian tablets contain a story about a great flood that destroyed Sumer. It is virtually the same story ascribed to Noah in the Old Testament. The same tablets also contain “ The Story of Gilgamesh” .

The world oldest known prescriptions, cuneiform tablets dating back to 2000 B.C. from Nippur, Sumer, described how to make poultices, salves and washes. The ingredients, which included mustard, fig, myrrh, bat dropping, turtle shell powder, river silt, snakeskins and "hair from the stomach of a cow," were dissolved into wine, milk and beer.

The oldest known recipe dates back to 2200 B.C. It called for snake skin, beer and dried plums to be mixed and cooked. Another tablet from the same period has the oldest recipe for beer. Babylonian tablets now housed at Yale University also listed recipes. One of the two dozen recipes, written in a language only deciphered in the last century, described making a stew of kid (young goat) with garlic, onions and sour milk. Other stews were made from pigeon, mutton and spleen.

Reports in Ancient Mesopotamia

Documents stored in libraries maintained by a succession of rulers. Tablets reported on international trade, described different jobs, kept track of cattle allotments to civil servants and recorded grain payments to the king.

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: Cuneiform private and public correspondence includes references to judicial or quasi-judicial acts that have a bearing on the practice of law in ancient Mesopotamia. The correspondence of private persons very often contains reports about dispositions of property in accordance with established customs, or possibly some references to legal action, which usually concerned questions of property. The correspondence of officials, including that of rulers, naturally concerned every area of political and economic administration, as well as other subjects, and occasionally mention materials directly pertinent to the subject of law. Among these are to be found the relatively scarce references to situations which would fall under the rubric of criminal law, as opposed to civil matters, with which all the other categories of private documents are almost exclusively concerned. Thus among the letters of Hammurapi of Babylon and of his older contemporary Rîm-Sin of Larsa there are references to official corruption and how the king dealt with it, and a royal order for the execution of an individual charged with homicide. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

The category of material that may be defined as literature provides still another source of information about the legal institutions of the area. From sources such as proverbs, didactic compositions of various kinds, wisdom literature, and even from epics and legends, may be culled a not inconsiderable amount of information about legal behavior in ancient Mesopotamia. Although these categories of documents constitute the only body of evidence for the actual practice of law in the cuneiform civilizations, the private documents must be utilized in a systematic way for the reconstruction of the real legal institutions of these societies themselves. It is often difficult also to assess the degree to which usages and procedures observed in the private documents represent true and fast "rules" or at least established custom; they may represent nothing more than the momentary whims of kings and officials without having the status of fixed rules or precedents. This condition contrasts with the formal legal corpora, which at least pretend to represent rules designed for application in all like cases and conditions, and which certainly represent the consensus on ideal moral and legal practice within the societies for which they were propounded.

Royal Inscriptions

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: Royal inscriptions are among the most important sources of ancient Near Eastern history. One of the most intriguing examples is found on the statue of King Idrimi, who ruled Alalakh, a city in present-day Turkey, in the fifteenth century B.C. A lengthy cuneiform inscription sprawls across the statue, spinning a first-person tale of exile, triumph, and redemption. “In Aleppo, the house of my father,” it begins, “a bad thing occurred, so we fled to the Emarites, my mother’s kin.” Idrimi, a younger son unwilling to play a diminished role, decamps for Canaan, where he finds countrymen who recognize his royal lineage. With their help, he wins over his home city and is proclaimed its rightful ruler by the king of Mitanni, the major regional power. Idrimi then repairs Alalakh’s toppled city wall, conquers more cities, builds a palace, cares for his people, and performs the necessary prayers and sacrifices. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

“The portion of the inscription that covers Idrimi’s reign is very similar to inscriptions left behind by kings from across the ancient Near East, from Hammurabi of Babylonia (r. 1792–1750 B.C.) to Ashurnasirpal II of Assyria (r. 883–859 B.C.). “The things Idrimi does once he becomes king are the things that Near Eastern kings conventionally claimed to have done in their inscriptions,” says Jacob Lauinger, an Assyriologist at Johns Hopkins University. However, Lauinger adds, the portion covering Idrimi’s exile is more akin to the Old Testament stories of Joseph and David, both younger sons who reach great heights. Just as the inscription’s narrative is a hybrid, so is its language. It is written in Akkadian cuneiform — as was only proper for a royal inscription at the time — but with clear Canaanite influences, such as the placement of verbs at the beginning of clauses.

“Although the text reads as if written by Idrimi during his reign, a recent reanalysis of the statue’s stratigraphy suggests it may actually have been written several decades later. As scholars continue to puzzle over this most unusual royal inscription, the wish expressed in its final lines has been fulfilled: “I wrote my service down on my tablet. May one regularly look upon them [the words] so that they [the words] may call blessings on me regularly.”

“During the millennia in which cuneiform script was used, Mesopotamia saw city-states jockey for resources, empires grow and dissipate, and seemingly countless kings made and unmade on the battlefield. Successful military campaigns brought land and resources, affirmed royal power, and granted privileged access to the gods. In turn, sculptures, reliefs, and cuneiform writings were commissioned to memorialize victories and legitimize claims. The Stela of the Vultures documents one of these conflicts from Sumer’s Early Dynastic III period (2600–2350 B.C.). “The monument stands at the beginning of a long line of historical narratives in the history of art,” says Irene J. Winter, a professor emeritus at Harvard University, in her analysis of the stela.

Laments on the ruin of Ur

Sumerian Writing and Other Languages

The Sumerian language endured in Mesopotamia for about a thousand years. The Akkadians, the Babylonians, Elbaites, Elamites, Hittites, Hurrians, Ugaritans, Persians and the other Mesopotamian and Near Eastern cultures that followed the Sumerians adapted Sumerian writing to their own languages.

Written Sumerian was adopted with relatively few modifications by the Babylonians and Assyrians. Other peoples such as Elamites, Hurrians, and Ugaritans felt that mastering the Sumerian system was too difficult and devised a simplified syllabary, eliminating many of the Sumerian word-signs.

Archaic Sumerian, the earliest written language in the world, remains as one of the written languages that have not been deciphered. Others include the Minoan language of Crete; the pre-Roman writing from the Iberian tribes of Spain; Sinaitic, believed to be a precursor of Hebrew; Futhark runes from Scandinavia; Elamite from Iran; the writing of Mohenjo-Dam, the ancient Indus River culture; and the earliest Egyptian hieroglyphics;

See Separate Article: MESOPOTAMIAN WRITING: DIFFERENT LANGUAGES, AND DECIPHERING AND TRANSLATING CUNEIFORM africame.factsanddetails.com

Books and Libraries in Ancient Mesopotamia

A book generally consisted of several tablets, which may consequently be compared with our chapters. At the end of each tablet was a colophon stating what was its number in the series to which it belonged, and giving the first line of the next tablet. The series received its name from the words with which it began; thus the fourth tablet or chapter of the “Epic of the Creation” states that it contains “one hundred and forty-six lines of the fourth tablet (of the work beginning) ‘When on high unproclaimed,’ ” and adds the first line of the tablet which follows. Catalogues were made of the standard books to be found in a library, giving the name of the author and the first line of each; so that it was easy for the reader or librarian to find both the work he wanted and the particular chapter in it he wished to consult. The books were arranged on shelves; M. de Sarzec discovered about 32,000 of them at Tello in Southern Chaldea still in the order in which they had been put in the age of Gudea (2700 B.C.). [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Literature of every kind was represented. History and chronology, geography and law, private and public correspondence, despatches from generals and proclamations of the king, philology and mathematics, natural science in the shape of lists of bears and birds, insects and stones, astronomy and astrology, theology and the pseudo-science of omens, all found a place on the shelves, as well as poems and purely literary works. Copies of deeds and contracts, of legal decisions, and even inventories of the property of private individuals, were also stored in the libraries of Babylonia and Assyria, which were thus libraries and archive-chambers in one.

In Babylonia every great city had its collection of books, and scribes were kept constantly employed in it, copying and re-editing the older literature, or providing new works for readers. The re-editing was done with scrupulous care. Where a character was lost in the original text by a fracture of the tablet, the copyist stated the fact, and added whether the loss was recent or not. Where the form of the character was uncertain, both the signs which it resembled are given. Some idea may be formed of the honesty and care with which the Babylonian scribes worked from the fact that the compiler of the Babylonian Chronicle, which contains a synopsis of later Babylonian history, frankly states that he does “not know” the date of the battle of Khalulê, which was fought between the Babylonians and Sennacherib. The materials at his disposal did not enable him to settle it. It so happens that we are in a more fortunate position, as we are able to fix it with the help of the annals of the Assyrian King.

New texts were eagerly collected. The most precious spoils sent to Assur-bani-pal after the capture of the revolted Babylonian cities were tablets containing works which the library of Nineveh did not possess. The Babylonians and Assyrians made war upon men, not upon books, which were, moreover, under the protection of the gods. The library was usually within the walls of a temple; sometimes it was part of the archives of the temple itself. Hence the copying of a text was often undertaken as a pious work, which brought down upon the scribe the blessing of heaven and even the remission of his sins. That the library was open to the public we may infer from the character of some of the literature contained in it. This included private letters as well as contracts and legal documents which could be interesting only to the parties whom they concerned.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024