Home | Category: Medieval Period / Abbasids / Sharia / Abbasids

EARLY SHARIA

Tile on a wall at Nishapur with a hadith

Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr. Wrote in “A Concise History of the Middle East”: “At the dawn of Islamic history, the administration and enforcement of i the law was handled by the caliphs and their provincial governors. Greater complexity of society led to more specialization, and they began to appoint Muslims who knew the Quran and the sunnah (of the caliphs as well as of Muhammad) to serve as quadis or "judges." As the judicial system evolved, an aspiring qadi at first got his training under an experienced master jurist. The schools were instituted in the big city mosques for the training of one (or more) of the various legal rites. The training schools for propagandists of Isma'ili Shi'ism and later the madrasahs founded by the Seljuks and other Sunni dynasties became centers for training judges and legal experts. Students would read the law books and commentaries under the guidance of one or several masters. When they had memorized enough of the information to function as qadis, they would receive certification to practice on their own. [Source: Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr., “A Concise History of the Middle East,” Chapter. 8: Islamic Civilization, 1979, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu /~]

“Various other judicial offices also evolved; the mufti ("jurisconsult"), who gives authoritative answers to technical questions about the law for a court or sometimes for individuals; the shahid ("witness"), who certifies that a certain act took place, such as the signing of a contract; and the muhtasib (market inspector), who enforces the Shari'ah in public places. It is interesting to note that the Muslim legal system had and still has no lawyers; that is, opposing parties are not represented by attorneys in court cases. Muslims felt that an advocate or attorney might well enrich himself at the expense of the litigant or the criminal defendant. There were also no prosecutors or district attorneys. In most cases the qadi had to decide on the basis of the evidence presented by the litigants and the witnesses, guided by relevant sections of the Shari'ah and sometimes by the advice of a mufti. /~\

“The caliph was supposed to assure that justice prevailed in the ummah not by interpreting the Shari'ah, but by appointing the wisest and best qadis to administer it. True, many of the Umayyad caliphs flouted the Shari'ah in their personal lives, but its rules remained valid for the ummah as a whole. We must always distinguish between what an individual can get away with doing in his home (or palace, or dormitory room) and what he can do in public, in the possible presence of a police officer. But no Umayyad or Abbasid caliph could abolish the Shari'ah or claim that it did not apply to him as to all other Muslims. When the caliphs could no longer appoint qadis and other legal officers, the various sultans and princes who took over his powers had to do so. When the caliphate could no longer serve as the symbol of Muslim unity, then everyone's common acceptance of the Shari'ah bridged the barriers of contending sects and dynasties to unite Islam. Even when the Crusaders or Mongols entered the lands of Islam and tried to enforce other codes of conduct, Muslims went on following the Shari'ah in their everyday lives. And, to a degree that may surprise some Westerners, they still do. You can go into a bazaar (covered market) in Morocco and feel that it is, in ways you can sense even if you cannot express them, like bazaars in Turkey, Pakistan, or thirty other Muslim countries. A Sudanese student greets me with the same salam alaykum ("peace to you") that I have heard from Iranians and Algerians. The common performance of worship, observance of the Ramadan fast, and of course the pilgrimage to Mecca are all factors unifying Muslims from every part of the world. /~\

See Separate Article: HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF SHARIA (ISLAMIC LAW) africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Sharia: Sharia by Knut S. Vikør, Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Politics web.archive.org ; Encyclopædia Britannica britannica.com ; Four Sunni Schools of Thought masud.co.uk ;

Law by Norman Calder, Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World web.archive.org ;

Sharia Law in the International Legal Sphere – Yale University web.archive.org ;

'Recognizing Sharia' in Britain, anthropologist John R. Bowen discusses Britain's sharia courts bostonreview.net ;

"The Reward of the Omnipotent" late 19th Arabic manuscript about Sharia wdl.org; Islamic History: History of Islam: An encyclopedia of Islamic history historyofislam.com ; Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World oxfordislamicstudies.com ; Sacred Footsetps sacredfootsteps.com ;

Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ;

Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Abbasid Caliphate” by Tayeb El-Hibri Amazon.com ;

“Caliphate: The History of an Idea” by Hugh Kennedy Amazon.com ;

“Sharī'a: Theory, Practice, Transformations” by Wael B. Hallaq Amazon.com ;

“The Lawful and the Prohibited in Islam (Al-Halal Wal Haram Fil Islam) by Yusuf Al-Qaradawi Amazon.com ;

“The Four Juristic Schools: Their Founders, Development, Methodology & Legacy”

by Islamic Research Team Do Fatwa Kuwait Amazon.com ;

“Islamic Jurisprudence According to the Four Sunni Schools: Al-Fiqh 'Ala al-Madhahib al-Arba 'ah–Volume I Acts of Worship” by 'Abd al-Rahman al-Jazir Amazon.com ;

“The Great Caliphs: The Golden Age of the 'Abbasid Empire” by Amira K. Bennison Amazon.com ;

“Baghdad During the Abbasid Caliphate” by G Le Strange Amazon.com ;

“Pathfinders: The Golden Age Of Arabic Science” by Jim Al-Khalili Amazon.com ;

“The Arabs: A History” by Eugene Rogan Amazon.com ;

“The New Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 1, Formation of the Islamic World, 6th to 11th Centuries Amazon.com

Development of Islamic Law Under the Abbasids

Joseph Schacht wrote in the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”: “When the Umayyads were overthrown by the 'Abbasids in A.D. 750, Islamic law, though still in its formative stage, had acquired its essential features; the need of Arab Muslim society for a new legal system had been filled. The early 'Abbasids continued and reinforced the islamizing trend which had become more and more noticeable under the later Umayyads. For reasons of dynastic policy, and in order to differentiate themselves from their predecessors, the 'Abbasids posed as the protagonists of Islam, attracted specialists in religious law to their court, consultet them on problems within their competence, and set out to translate their doctrines into practice. But this effort was shortlived. The early specialists who had formulated their doctrine not on the basis of, but in a certain opposition to, Umayyad popular and administrative practice, had been ahead of realities, and now the early 'Abbasids and their religious advisers were unable to carry the whole of society with them. [Source: Joseph Schacht, “Law and Justice”, from the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”, vol. II, pt. VIII/Chapter 4, beginning with pg. 539, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu =^=]

page 1 of the Malaki text "The Commentary of the Šay , the Head, the Extremely Knowledgeable A mad al-Šāfiʻī al-Janājī al-Mālikī on the Commentary of the Šay al-Islām Zakarīyā al-An ārī on the Compendium on the Science of WDL"

“This double-sided effect of the 'Abbasid revolution shows itself clearly in the development of the office of qadi. The qadi was not any more the legal secretary of the governor; he was normally appointed by the caliph, and until relieved of his office, he must apply nothing but the sacred law, without interference from the government. But theoretically independent though they were, the qddis had to rely on the political authorities for the execution of their judgments, and being bound by the formal rules of the Islamic law of evidence, their inability to deal with criminal cases became apparent. (Under the Umayyads, they or the governors themselves had exercised whatever criminal justice came within their competence.) Therefore the administration of the greater part of criminal justice was taken over by the police, and it remained outside the sphere of practical application of Islamic law. The centralizing tendency of the early 'Abbasids also led, perhaps under the influence of a feature of Sassanid administration, to the creation of the office of chief qadi. It was originally an honoriflc title given to the qadi of the capital, but the chief qadi soon became one of the most important counsellors of the caliph, and the appointment and dismissal of the other qadis, under the authority of the caliph, became the main function of his office. =^=

“An institution which the early 'Abbasids, and perhaps already the later Umayyads, borrowed from the administrative tradition of the Sassanid kings was the 'investigation of complaints' concerning miscarriage or denial of justice, or other allegedly unlawful acts of the qadis, difficulties in securing the execution of judgments, wrongs committed by government officials or by powerful individuals, and similar matters. Very soon, formal courts of complaints were set up, and their jurisdiction became to a great extent concurrent with that of the qadis' tribunals. The very existence of these tribunals, which were established ostensibly in order to supplement the deficiencies of the jurisdiction of the qadis, shows that their administration of justice had largely broken down at an early period. since then, there has been a double administration of justice, one religious and the other secular, in practically the whole of the Islamic world. =^=

“At the same time, the office of the 'inspector of the market' was islamized. Its holder, in addition to his ancient functions, was now entrusted with discharging the collective obligations of enforcing Islamic morals, and he was given the Islamic title of muhtasib, it was now part of his duties to bring transgressors to justice and to impose summary punishments, which on occasion came to include the flogging of the drunk and the unchaste, and even the amputation of the hands of thieves caught in the act; but the eagerness of the rulers to enforce these provisions commonly made them overlook the fact that the procedure of the muhtasib did not always satisfy the strict demands of the law. =^=

“Whereas Islamic law had been adaptable and growing until the early 'Abbasid period, from then onwards it became increasingly rigid and set in its final mould. A doctrine which had to be derived exclusively from the Qur'an and, even more important, from a number of detailed Traditions from the Prophet, and became more and more hedged in by the ever growing area of the consensus of the scholars, and by the closing of the gate of ijtihad, was unable to keep pace with the changing demands of society and commerce. This essential rigidity of Islamic law helped it to maintain its stability over the centuries which saw the decay of the political institutions of Islam. From the early 'Abbasid period onwards, we notice an increasing gap between theory and practice.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Internet Medieval Sourcebook: J. Schacht::Law and Justice from the Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. II, pt. VIII/chpt. 4, beginning with pg. 539. sourcebooks.web.fordham.edu

Caliphs and Qadis Under the Abbasids

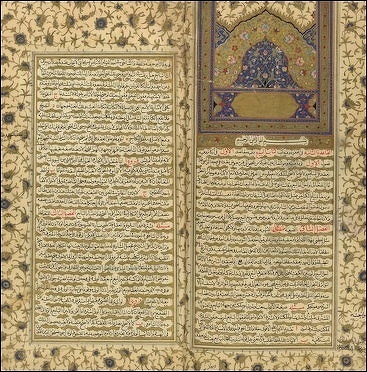

Shia fiqh: Tazkarat al-Fuqaha

Joseph Schacht wrote in the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”: “The caliph, too, was given a place in the religious law of Islam. He was endowed with the attributes of a religious scholar and lawyer, bound to the sacred law in the same way as qadis were bound to it, and given the same right to the exercise of personal opinion as was admitted by the schools of law. The caliph retained full judicial power, the qadis were merely his delegates, but he did not have the right to legislate; he could only make administrative regulations within the limits laid down by the sacred law, and the qadis were obliged to follow his instructions within those limits. This doctrine disregarded the fact that what was actually legislation on the part of the caliphs of Medina, and particularly of the Umayyads, had to a great extent entered the fabric of Islamic law. [Source: Joseph Schacht, “Law and Justice”, from the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”, vol. II, pt. VIII/Chapter 4, beginning with pg. 539, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu =^=]

The later caliphs and other secular rulers often enacted new rules; but although this was in fact legislation, the rulers used to call it administration, and they maintained the fiction that their regulations served only to apply, to supplement, and to enforce the sacred law. This ambiguity pervaded the whole of Islamic administration during the Middle Ages and beyond. In practice, the rulers were generally content with making regulations on matters which had escaped the control of the qads~, such as police, taxation and criminal justice. The most important examples of this kind of secular law are the siyasa of the Mamluk sultans of Egypt which applied to the military ruling class, and, later, the qanun-nama of the Ottoman sultans. Only in the present generation has a secular, modernist legislation, directly aimed at modifying Islamic law in its traditional form, come into being; this became possible only through the reception of Western political ideas. But the postulate that law, as well as other human relationships, must be ruled by religion, has become an essential part of the outlook of the Muslim Arabs, including the modernists among them. =^=

“Notwithstanding all this, the office of qadt in the form which it essentialiy acquired under the early 'Abbasids, proved to be one of the most vigorous institutions evolved by Islamic society. Qadis were often made military commanders, and examples are particularly numerous in Muslim Spain and in the Maghrib in general. They often played important political parts, although it is not always possible to distinguish the purely personal element from the prestige inherent in the office. Particularly in the Ayyubid and in the Mamluk periods, they were appointed to various administrative offices. They even became heads of principalities and founders of small dynasties from the fifth/eleventh century onwards, when the central power had disintegrated; there are especially numerous examples in Muslim Spain in the time of the Party Kings and others occur in Syria, Anatolia and Central Asia. In the Ottoman system of provincial administration, the qadi was the main authority in the area of his jurisdiction, and elsewhere, as in medieval Persia, he became the main representative of what is called the religious institution. To some extent the qadi (and the other religious scholars, too) were the spokesmen of the people; they played an important part not only in preserving the balance of the state but also in maintaining Islamic civilization, and in times of disorder they constituted an element of stability. Nevertheless, as far as the essence of the qadi's office was concerned, a real independence of the judiciary, though recognized in theory, was hardly ever achieved in practice. =^=

Becoming a Qadi in the Abbasid Period

Calligraphy name of Abu Hanifa, founder of the Hanifi Sharia school

On how he became a qadi (judge, magistrate), Al-Tanûkhî wrote in “Ruminations and Reminiscences” in A.D. 980: “The Caliph “said to me: ‘Sir, whenever you see any kind of wrong committed, great or small, or anything of the sort great or small, then order it to be righted and remonstrate about it, even with him (pointing to Badr); and if anything befalls you and you are not listened to, then the sign between us is that you sound the call to prayer at about this time; I, hearing your voice, will summon you and will do this to any one who refuses to listen to you, or injures you.' I invoked a blessing on him and departed; then the rumor spread among the Dailemites and the Turks, and I have never asked any one to right another or to desist from wrong-doing, but he has obeyed me to my satisfaction for fear of Mu'tadid, so that up to this time I have not had to sound the call." “[Source: D. S. Margoliouth, ed., The Table Talk of a Mesopotamian Judge, (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1922), pp. 64-67, 164-68, 135-37, 93, 2 9-92, 86-87, 31, 160, 97-101, 172-73, 84-86, 204-6]

“I was told by my father that when Abu Yusuf cultivated the society of Abu Hanifah in order to learn law, he was very poor, and his attendance on his teacher prevented him from earning his livelihood. So he used to return at the end of the day to short rations in an ill-appointed establishment. This went on a long time, his wife resorting to various expedients in order to maintain herself day by day. At last her patience was exhausted, and when one day he had gone to the lecture-room, spent the whole day there, and returned at night to ask for his meal, she produced a covered dish. When he removed the cover he found it to contain some note-books. To his question what this meant, she replied that it was what he was occupied with the whole day, so he had better eat it at night. Deeply affected, he went without food that night, and stayed away from the lecture next morning until he had secured some food for the household. Coming then to Abu Hanifah, and being asked why he was so late, he told the truth. Why, asked Abu Hanifah, did you not tell me, so that I might have helped you? You need not be anxious; if your life is preserved your legal earnings will enable you to feast on almond paste and shelled pistachios. Abu Yusuf stated that when he had entered the service of Rashid [Caliph, r. 786-809], and enjoyed his favor, one day a dish of almond paste and pistachios was brought to the imperial table. When I tasted it, he said, tears came to my eyes, as I remembered Abu Hanifah. When Rashid asked me the reason of my emotion, I told him this story.

quote from Abu Yusuf, a student of Hanafi that helped spread his school

“The occasion, said my father, of Abu Yusuf entering the service of Rashid was that one of the generals had forsworn himself, and wished to consult a jurist on the matter. Abu Yusuf, being fetched, gave it as his opinion that he had not forsworn himself; and the general presented him with some dinars, took a house for him near his own, and attached him to himself. One day when the general visited Rashid, he found him depressed, and, inquiring the reason, was told that the Caliph was troubled by a religious question, and requested him to fetch a jurist whom he might consult. The general brought Abu Yusuf. Abu Yusuf narrated as follows: Entering a corridor between the apartments, I saw a handsome lad with the marks of royalty upon him, imprisoned in one of the chambers which opened on the corridor. The lad made a sign to me with his finger, to implore my assistance, but I did not understand his meaning. I was then taken into the presence of Rashid, and when I appeared before him, I saluted and stood. He asked me my name, to which I replied, Ya'qub, God prosper the Commander of the Faithful. He then said: What say you of a sovereign who witnesses a man committing a mortal sin? Must he inflict the penalty? Not necessarily, I replied. When I said this, Rashid prostrated himself, and it occurred to me that he must have seen one of his own sons committing that offence and that the person who had signalled to me for assistance was the adulterous son. Presently Rashid raised his head and asked me my authority. Because, I replied, the Prophet said: "Avert penalties by doubts," and there is here a doubt which invalidates the penalty.

“What doubt is there, he asked, when there is ocular evidence? Ocular evidence, I replied, does not necessitate it any more than knowledge of the occurrence would necessitate it; and the law does not inflict penalties from mere knowledge. Why? he asked. Because, I replied, the penalty is a right of God, which the sovereign is commanded to maintain, so that it becomes as it were his own right; and no person may exact his right by virtue of his own knowledge, nor himself enforce it. The Muslims are agreed that the penalty requires for its enforcement confession or evidence. They are not agreed that knowledge is sufficient to necessitate its enforcement. Thereupon Rashid prostrated himself a second time, and ordered that I should be given a vast sum as well as a monthly allowance among the jurists, and that I should be attached to the Palace. Before I had got outside I received a gift from the young man and another from his mother, and others from his followers, and thereby I got the foundation of a fortune. The Caliph's allowance was added to the allowance which I was receiving from the general, and, being attached to the Palace, I was asked for an opinion by one servant and for advice by another, and by giving opinions and advice I gained authority with them and won their respect, and presents kept reaching me from them, so that my position strengthened. Then the Caliph summoned me to a lengthy interview, to ask my opinion concerning an emergency, and treated me with cordiality; and I proceeded to advance in his favor until he made me judge.”

Activity of Qadi (Magistrate) in the Abbasid Period

Abbasid qadi

In “Ruminations and Reminiscences,” Al-Tanûkhî wrote in A.D. 980: “I was told by the Qadi Abu Bakr Muhammad bin ‘Abd al-Rahman that he had been informed by a steward of Abu'l-Mundhir Nu'man bin ‘Abdallah how it was the latter's custom at the close of the winter season to collect all the poplin, wool, blankets, stoves and other appliances for winter which he had been using and sell them by auction; he would then send to the Qadi's prison and find out what prisoners were there in consequence of their own confessions (not of evidence brought against them, and were without means. He would pay their debts out of the price obtained for these goods, or else would make a settlement permitting of their release, if the debt was heavy. [Source: D. S. Margoliouth, ed., The Table Talk of a Mesopotamian Judge, (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1922), pp. 64-67, 164-68, 135-37, 93, 2 9-92, 86-87, 31, 160, 97-101, 172-73, 84-86, 204-6]

“He would then turn his attention to small dealers such as confectioners and pedlars, people whose business capital was from one to three dinars, and give them some sum such as ten dinars or a hundred dirhems as additional capital. He would also turn his attention to those who were selling in the market such things as kettles, pots, torn shirts, etc. which would probably only be sold owing to extreme need, and to old women who were selling their spinning, give them many times the value of the articles, and allow them to retain them. Many more things of this sort would he do, and order me to carry out, expending the price of his goods on these objects. When winter came he would similarly collect his dabiqi, gold and silver network, matting, water-coolers, and other appliances for summer, and deal with them in the same way. When next summer or winter came, he would get in fresh supplies of everything he wanted.

“When I grew tired of this procedure on his part, I said to him: "Sir, you are crippling yourself without achieving any profitable result; for you are buying these garments, instruments and furniture at abnormally high prices at the times when there is a demand for them, whereas you sell them at the season when there is no demand for them, and get in consequence no more than half price. Thereby you lose a vast sum. If you will permit, I will put all you want sold up to auction, and when they are about to be knocked down, will buy them in for you at a higher price, reserve them for you for the summer or winter, and devote out of your estate an amount equal to that for which they were knocked down to these objects." He said: "I do not want this done. These are goods which God has permitted me to enjoy throughout my summer or winter, and He has brought me to the time wherein I can dispense with them. I have no assurance that I shall live to the time when I shall need them again. Possibly I may have offended God either for them or with them. I prefer to sell the articles themselves, and devote the actual price to these objects, by way of thanking God for having brought me to the time wherein I no longer need them, and as compensation for any offence which I may have committed in connection with them. Then if God spare me for the time when I shall require them, they will not be very costly and I shall have no difficulty in purchasing the like, renewing my stock and enjoying the new articles. There is a further advantage about my selling them cheap and buying them dear, which is that the poorer dealers from whom I buy and to whom I sell will get the profit from me, whereas this will not affect my fortune."

Collecting a Debt in the Abbasid Period

Abbasid coins

In “Ruminations and Reminiscences,” Al-Tanûkhî wrote in A.D. 980: “I was told by the Qadi Abu'l-Hasan Muhammad bin Qadi 'Abd al-Wahid Hashimi that a large sum was owed to a leading tradesman by one of the generals, who deferred paying; and, said the tradesman, "I made up my mind to appeal to Mu'tadid [Caliph, r. 892-902], because whenever I went to the general, he had the door shut against me and let his slaves revile me, whereas if I tried mild methods and used mediation, it was useless.... Then one of my friends said to me: ‘I will recover your money, and you need not appeal to the Caliph. Come with me at once.' ‘So,' said he, ‘I arose and he brought me to a tailor in Tuesday Street, an old man who was seated, sewing and reading the Quran. Telling him my story, he asked him to call on the general, and see me righted. The general's residence was near the tailor's, and the latter started with us. As we were walking, I lagged behind and said to my friend: "You are exposing this aged man, yourself, and me to serious annoyance. When he comes to the door of my debtor, he will be cuffed, and you and I with him. For the general paid no attention to the remonstrances of So-and-so, and So-and-so, nor even troubled about the vizier. Is he likely to trouble about our friend here?" My friend laughed and said: "Never mind, walk on and keep quiet." “[Source: D. S. Margoliouth, ed., The Table Talk of a Mesopotamian Judge, (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1922), pp. 64-67, 164-68, 135-37, 93, 2 9-92, 86-87, 31, 160, 97-101, 172-73, 84-86, 204-6]

“After obtaining their attestations I left with them; and when we reached the tailor's place I flung down the money before him, saying: "Sir, through you God has restored me my property, and I shall be pleased if you will accept a quarter, a a third, or a half of it, which I gladly offer." "Friend," he replied, "you are indeed in a hurry to return evil for good! Take yourself off with your property, with the blessing of God!" I said that I had one more request. When he bade me utter it, I asked him to tell me the reason why the general had yielded to him, when he had treated the greatest men in the empire with contempt. "Sir," he replied, "you have got what you wanted, so please do not interrupt me in the occupation by which I earn my livelihood." When I insisted, he said: "I have been a leader of prayer and have been teaching the Qur'an in this mosque for forty years, earning my living by tailoring which is the only trade I know.

“A’We arrived at the general's door, and when his slaves saw the tailor, they treated him with reverence, and rushed to kiss his hand, which he would not permit. Then they said: "What has brought you, sir? The master is riding, and if it be something which we can do, we shall do it at once; but if not, then come in and sit down ‘till he comes." This encouraged me, and we went inside and sat down. Presently the man came, and when he saw the tailor, he was most respectful, and said: "Before I change my clothes you must give me your orders." The tailor then spoke to him about my affair. He assured the tailor that he had not in his house more than five thousand dirhems, but begged him to take those and his silver and gold harness as pledges for the rest which he would pay within a month. I readily assented, and he produced the dirhems and the harness to the value of the remainder; of this I took possession, and made the tailor and my friend attest the arrangement whereby the pledge for the remainder of the money was to remain in my possession for a month, and if this term were exceeded I was at liberty to sell it and recoup myself from the proceeds.

Abduction of Woman and Punishment for It

In “Ruminations and Reminiscences,” Al-Tanûkhî wrote in A.D. 980:“A long time ago, after saying the sunset prayer, as I was going homewards I passed by a Turk, who was in this house. Suddenly a woman of fair countenance passed by, and the Turk who was drunk seized hold of her, trying to drag her into the house, while she resisted and called for help, which was not forthcoming, no one coming forward to rescue her from the Turk in spite of her cries. Among other things she was saying that her husband had sworn he would divorce her if she spent a night away from his house, and if the Turk compelled her to disobey this he would ruin her home in addition to the crime which he could be committing, and the disgrace which he would bring upon her." “[Source: D. S. Margoliouth, ed., The Table Talk of a Mesopotamian Judge, (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1922), pp. 64-67, 164-68, 135-37, 93, 2 9-92, 86-87, 31, 160, 97-101, 172-73, 84-86, 204-6]

“"I went up to the Turk and stopped him, requesting him to let the woman go, but he struck me on the head with a club that was in his hand, giving me a painful wound, and forced the woman to enter the house. I went home, washed off the blood, bound up the wound, and when the pain had eased went out to say the evening prayer. When that was over I said to the congregation: ‘Come with me to this godless Turk, to remonstrate with him, and not leave him until we make him release the woman.' They rose up, and we went and made a great noise at his door, and presently he came out at the head of a number of his slaves, raining blows upon us, and he singled me out, striking me a blow of which I nearly died. My neighbors carried me to my dwelling in a dying condition. My family treated my wounds, and I slept, but very slightly owing to the pain, and I woke up at midnight and could sleep no longer as I thought about the affair. Then I said to myself: The fellow must have been drinking all night, and will not know the time; if I sound the call to prayer, he will suppose that the dawn has commenced, and will release the woman so that she can reach her house before dawn. She will thus escape from one of the two disasters, and her home will not be ruined in addition to what has befallen her. So I went out to the mosque walking as best I could, and mounting the minaret, sounded the call, and then sat down and looked out upon the street, waiting to see the woman come out; if she did not come out, I would start prayer, that there might be no doubt in the Turk's mind that it was morning and he might release her.

Only a little while elapsed and the woman was still with him when the street became filled with horse and foot, with torches, and men crying: ‘Who is it who has just been calling to prayer? Where is he?' At first I was too terrified to speak, but then I thought I would address them and perhaps get help for the woman. So I called out from the minaret: ‘I was the person.' They said to me: ‘Come down and answer the Commander of the Faithful.' Thinking to myself that deliverance was near, I descended, and went with them, and found them to be a company of guards with Badr, who brought me before Mu'tadid. When I saw him, I shook and trembled, but he encouraged me, and then asked me what had induced me to alarm the Muslims by sounding the call to prayer at a wrong time, so that people who had business would go about it prematurely, and those who meant to fast would restrain themselves at a time when they were allowed to break their fast. I said: ‘If the Commander of the Faithful will grant me amnesty, I will tell the truth.' He told me my life was safe. I then recounted to him the story of the Turk, and showed him the marks upon me, and he ordered Badr at once to bring the soldier and the woman."

“"I was taken apart, and after a short time the soldier and the woman were produced, and Mu'tadid proceeded to ask her about the affair, which she narrated as I had done. Mu'tadid then ordered Badr to send her at once to her husband with a trustworthy escort, who should bring her into her house and explain the affair to her husband, with a request from the Caliph to him not to send her away, but to treat her kindly. He then summoned me, and while I stood listening, he began to question the soldier as follows: ‘How much, fellow, is your allowance?' He gave the amount. ‘Your pay?' So much. ‘Your perquisites?' So much. Then he began to enumerate the gratuities which the man received, and the Turk acknowledged to an enormous amount. Then he asked him how many slave-girls he possessed. He gave the number.

“The Caliph said to him: ‘Were not these and the ample fortune which you enjoyed sufficient for you, but you must needs violate the commands of God, and injure the majesty of the Sultan, and not only perpetrate this offence, but in addition assault the person who tried to make you do right?' The soldier was conscience-smitten and could make no reply. The Caliph then ordered them to fetch a sack, some cement-makers' pestles, bonds and fetters. The man was bound and fettered, and put into the sack, and the attendants were then ordered to pound him with the pestles. "This was done in my sight, and for a time the man screamed, then his voice stopped as he was dead. The Caliph ordered the body to be thrown into the Tigris, and told Badr to seize the contents of his dwelling.

Crime and Fraud the Abbasid Empire

In “Ruminations and Reminiscences,” Al-Tanûkhî wrote in A.D. 980: “The following is a curious device put in practice by a thief in our time. I was informed by Abu'l-Qasim 'Ubaidallah bin Muhammad the Shoemaker that he had seen a thief caught and charged with picking the locks of small tenements supposed to be occupied by unmarried persons. Entering the house he would dig a hole such as is called "the well" in the nard game, and throw some nuts into it as though some one had been playing with him, and leave by the side a handkerchief containing some two hundred nuts. He would then proceed to wrap up as many of the goods in the house as he could carry, and if he passed unobserved, he would depart with his burden. If, however the master of the house came on the scene, he would abandon the loot and endeavor to fight his way out. If the master of the house proved doughty, sprung upon him, held him, tried to arrest him, and called out Thieves!, and the neighbors assembled, he would address the master of the house as follows: You are really wanting in humor. Here have I been playing nuts with you for months, and, though you beggared me and took away all I possessed, I made no complaint, nor did I shame you before your neighbors; and now that I have won your goods, you begin to charge me with larceny, you mean and wretched creature! Between us is the gambling-house, the place where we became acquainted. State in the presence of the people there or of the people here that I have cheated, and I will leave you your goods. The man might continue to assert that the other was a thief, but the neighbors supposed that he was unwilling to be branded as a gambler, and in consequence charged the other with theft; whereas in reality he was a gambler and the other man was speaking the truth. They would endeavor to make peace between the two, presently the thief would walk away with his nuts, and the master of the house would be defamed. [Source: D. S. Margoliouth, ed., The Table Talk of a Mesopotamian Judge, (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1922), pp. 64-67, 164-68, 135-37, 93, 2 9-92, 86-87, 31, 160, 97-101, 172-73, 84-86, 204-6]

from Arabian Nights

“He informed me that he knew of another whose plan was to enter the residences of families, especially those in which there were women whose husbands were out. If he succeeded in getting anything he would go away; if he were perceived and the master of the house came, he would suggest that he was a friend of the wife, and some officer's retainer; and ask the master to keep the matter quiet from his employer for the sake of both; displaying a uniform, and suggesting that if the master chose to dishonor his household, he could not bring him before the Sultan on a charge of adultery. However much the master might shout Thief!, he would repeat his story, and when the neighbors assembled, they would advise the master of the house to hush the matter up. When the master objected, they would attribute his conduct to marital affection and help the thief to escape from his hand. Sometimes they would compel the master to let the thief go. Likewise the more the wife denied and swore with tears that the man was a thief, the more inclined would they be to let him go; so he would get off, and the master would afterwards divorce his wife, and part from his children's mother. This thief thus ruined more than one home and impoverished others, until he went into a house where there was an old woman aged more than ninety years; he not knowing of this. Caught by the master of the house he tried to make his usual insinuation; the master said to him: Scoundrel! There is no one in the house but my mother, who is ninety years old and for more than fifty of them she has spent her nights in prayer and her days in fasting; do you maintain that she is carrying on an amour with you or you with her? So he hit him on the jaw and when the neighbors came together and the thief told them the same story they told him he lied, they knowing the old lady's piety and devoutness. Finally he confessed the facts and was taken off to the magistrate.

“I was told by Abu Muhammad 'Abdallah bin 'Umar al-Harithi, on the authority of a professional connoisseur of stones with peculiar properties, who was of Khorasan, the following story. I passed, he said, by a pedlar in Egypt, and noticed that he had a stone with which I was acquainted, pretty to look at and weighing five drachms. He had put it in front of him among his goods. I was aware that it possessed the property of driving away flies, and had been on the look out for it for many years. When I saw it, I made a bid for it, and when he demanded five dirhems, I did not beat him down, but gave him the coins in good money. When they were in his possession and the stone in mine, he began to indulge in mirth at my expense, saying: How easily we can gull these asses who do not know what they give or what they take! I assure you I saw this pebble only a few days ago in the hands of a child, and gave him one sixth of a dirhem for it; and here has this fool been giving me five dirhems for it! I turned back and said to him: I would have you know that you are the fool, not I. How so, he asked. Come with me, I said, and I will show you. So I made him come, and presently we came to a huckster who was selling dates out of a dish, and the flies were buzzing all about. Bidding the man stand at a little distance from the dish, I placed the stone upon it, and when it was there all the flies flew away and left it, and for a time there was not a single fly there. Presently I took the stone away and the flies returned; then I replaced the stone and the flies flew off. I did this three times, then I concealed the stone, and said: Fool, this is the flystone, in search of which I have come the whole way from Khorasan. Among us, kings place it on their tables, and the flies will not come near, whence no fans nor flyflaps are required. Had you asked five hundred dinars for it, I should have given them you. The man heaved a deep sigh, so deep that I thought his end had come; after a time he recovered, and we parted. After some days I went off to Khorasan, having in my possession the stone, which I sold to Nasr bin Ahmad the governor for ten thousand dirhems.

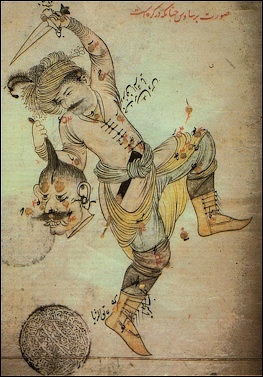

Torture in the Abbasid Empire

In “Ruminations and Reminiscences,” Al-Tanûkhî wrote in A.D. 980: “Among stories of extraordinary endurance is the following: When Babak al-Khurrami and his colleague Maziyar were brought before Mu'tasim [Caliph, r. 833-841], the latter said to the former: Babak, you have perpetrated what no-one before has perpetrated, now exhibit unparalleled endurance. Babak said: You shall see. When they were brought into the presence of Mu'tasim, the Caliph ordered their hands and feet to be amputated before him. The executioner commenced with Babak, whose right hand was amputated; as the blood began to flow, Babak began to smear therewith the whole of his face, until it was entirely disfigured thereby. [Source: D. S. Margoliouth, ed., The Table Talk of a Mesopotamian Judge, (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1922), pp. 64-67, 164-68, 135-37, 93, 2 9-92, 86-87, 31, 160, 97-101, 172-73, 84-86, 204-6]

“Mu'tasim bade them ask Babak why he did this. Being asked, he replied: Tell the Caliph thus: You have ordered my four limbs to be amputated, and are determined on my death; you are doubtless not going to cauterize the stumps, but will allow the blood to flow until I am decapitated. I was afraid the blood might flow out to such an extent that my face would be left pale, in which case those present might conclude from this paleness that I was afraid of death, supposing this rather than the loss of blood to be its cause; hence I smeared the blood all over my face that no such paleness might be seen.

“Mu'tasim said: Were it not that his crimes do not permit his being pardoned, he would deserve to be spared for this heroism. He then ordered the executioner's work to continue. After the four limbs had been amputated he was beheaded, the severed members were then placed on the trunk, naphtha was then poured upon them, and the whole set on fire. The same was done to his colleague and not one of them uttered a cry or a groan.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); Metropolitan Museum of Art, Encyclopedia.com, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024