HISTORY OF SHARIA

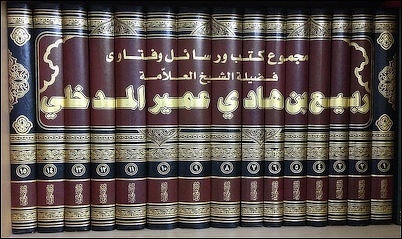

Hanbali Fiqh Musnad

Islamic Law, or Sharia, s a set of legal codes based on scriptures from the Qur'an (the Muslim holy book), the Hadith (sayings and conduct of the prophet Muhammad) and fatwas (the rulings of Islamic scholars) — and interpretations of these scriptures by classical Islamic schools of thought. Governing public, private, social, religious and political life of Muslims, the laws are based on the principal that Qur’anic commands are divine and absolute and can not be questioned. All aspects of a Muslim's life are governed by Sharia. Muslim law tells followers how to perform their prayers, how to pay their alms, how to observe the fast. It also describes how Muslims should dress, what food Muslims can eat and even what greetings can be exchanged. Sharia is expected to be abided by as a system of laws and rules for living. It also sets forth an ethical ideal of which one is supposed to conform to.

During his lifetime, Muhammad was both spiritual and temporal leader of the Muslim community. He established the concept of Islam as a total and all-encompassing way of life for both individuals and society. Muslims believe that God revealed to Muhammad the rules governing decent behavior. It is therefore incumbent on the individual to live in the manner prescribed by revealed law and on the community to perfect human society on earth according to the holy injunctions. Islam recognizes no distinction between religion and state. Religious and secular life merge, as do religious and secular law. In keeping with this conception of society, all Muslims traditionally have been subject to religious law, or sharia. [Source: Library of Congress]

As a comprehensive legal system, sharia developed gradually through the first four centuries of Islam, primarily through the accretion of precedent and interpretation by various judges and scholars. During the tenth century, legal opinion began to harden into authoritative rulings, and the figurative bab al ijtihad (gate of interpretation) closed. Thereafter, rather than encouraging flexibility, Islamic law emphasized maintenance of the status quo.

Joseph Schacht wrote in the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”: “The sacred law of Islam, the Shari'a, occupies a central place in Muslim society, and its history runs parallel with the history of Islamic civilization. It has often been said that Islamic law represents the core and kernel of Islam itself and, certainly, religious law is incomparably more important in the religion of Islam than theology. As recently as 1959, the then rector of al-Azhar University, Shaykh Mahmud Shaltut, published a book entitled 'Islam, a faith and a law' (al-Islam, 'aqida wa-shari'a), and by far the greater part of its pages is devoted to an expose of the religious law of Islam, down to some technicalities, whereas the statement of the Islamic faith occupies less than one-tenth of the whole. It seems that in the eyes of this high Islamic dignitary the essential bond that unites the Muslims is not so much a common simple creed as a common way of life, a common ideal of society. [Source:Joseph Schacht, “Law and Justice”, from the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”, vol. II, pt. VIII/Chapter 4, beginning with pg. 539, Schacht (1902-1969) was a professor at Columbia University and expert on Muslim law. Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu =^=]

“The development of all religious sciences, and therefore of a considerable part of intellectual life in Islam, takes its rhythm from the development of religious law. Even in modern times, the main intellectual effort of the Muslims as Muslims is aimed not at proving the truth of Islamic dogma but at justifying the validity of Islamic law as they understand it. It will therefore be indicated for us to survey the development of Islamic law within the framework of Islamic society and civilization, tentative as this survey is bound to be. Islamic law itself is one of our most important sources for the investigation of Islamic society, and explaining Islamic law in terms of Islamic society risks using a circular argument. Besides, the scarcity of expert historical and sociological studies of Islamic law has more often been deplored than it has inspired efforts to fill this gap.” =^=

Websites on Sharia: Oxford Dictionary of Islam /web.archive.org ; Encyclopædia Britannica britannica.com ; Four Sunni Schools of Thought masud.co.uk ; Sharia by Knut S. Vikør, Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Politics web.archive.org ; Law by Norman Calder, Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World web.archive.org ; Sharia Law in the International Legal Sphere – Yale University web.archive.org ; 'Recognizing Sharia' in Britain, anthropologist John R. Bowen discusses Britain's sharia courts bostonreview.net ; "The Reward of the Omnipotent" late 19th Arabic manuscript about Sharia wdl.org

See Separate Articles:

SHARIA (ISLAMIC LAW): SOURCES, PRINCIPALS, SOCIETY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FOUR SCHOOLS OF SUNNI SHARIA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ISLAMIC JUSTICE SYSTEM: COURTS, QADIS (JUDGES) AND FATWAS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

EXTREME SHARIAH PUNISHMENTS factsanddetails.com ;

MUSLIM VIEWS AND INTERPRETATIONS OF SHARIA africame.factsanddetails.com

BLASPHEMY, APOSTASY AND SHARIA africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Sharī'a: Theory, Practice, Transformations” by Wael B. Hallaq Amazon.com ;

“The Lawful and the Prohibited in Islam (Al-Halal Wal Haram Fil Islam) by Yusuf Al-Qaradawi Amazon.com ;

“Sharia Law for Non-Muslims” by Bill Warner PhD, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Introduction to Islamic Law: Principles of Civil, Criminal, and International Law under the Shari‘a” by Jonathan G. Burns Amazon.com ;

“Sharia Incorporated: A Comparative Overview of the Legal Systems of Twelve Muslim Countries in Past and Present” by Isabell Otto Amazon.com ;

“An Introduction to Islamic Law” by Wael B. B. Hallaq Amazon.com ;

“Islamic Jurisprudence According to the Four Sunni Schools: Al-Fiqh 'Ala al-Madhahib al-Arba 'ah–Volume I Acts of Worship” by 'Abd al-Rahman al-Jazir Amazon.com ;

“The Four Juristic Schools: Their Founders, Development, Methodology & Legacy”

by Islamic Research Team Do Fatwa Kuwait Amazon.com ;

“Blasphemy and Apostasy in Islam: Debates in Shi’a Jurisprudence” by Mohsen Kadivar, Hamid Mavani, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Islam Explained: A Short Introduction to History, Teachings, and Culture” by Ahmad Rashid Salim Amazon.com ;

“No God but God” by Reza Aslan Amazon.com ;

“Welcome to Islam: A Step-by-Step Guide for New Muslims” by Mustafa Umar Amazon.com

Roots of Islamic Law

Bronze man from pre-Islamic Yemen

Joseph Schacht wrote in the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”: “Islamic law had its roots in pre-Islamic Arab society. This society and its law showed both profane and magical features. The law was magical in so far as the rules of investigation and evidence were dominated by sacral procedures, such as divination, oath, and curse; and it was profane in so far as even penal law was reduced to questions of compensation and payment. There are no indications that a sacred law existed among the pagan Arabs; this was an innovation of Islam. The magical element left only faint traces, but Islamic law preserved the profane character of a considerable portion of penal law. It also preserved the essential features of the law of personal status, family, and inheritance as it existed, no doubt with considerable variations of detail, both in the cities and among the bedouin of Arabia. [Source: Joseph Schacht, “Law and Justice”, from the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”, vol. II, pt. VIII/Chapter 4, beginning with pg. 539, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu =^=]

“All these subjects were dominated by the ancient Arabian tribal system, combined with a patriarchal structure of the family. Under this system, the individual lacked legal protection outside his tribe, the concept of criminal justice was absent and crimes were reduced to torts, and the tribal group was responsible for the acts of its members. This led to blood feuds, but blood feuds were not an institution of ancient Arab tribal law, they stood outside the law and came under the purview of the law only when they were mitigated by the payment of blood-money, and at this moment the profane character of ancient Arabian law asserted itself again. There was no organized political authority in pre-Islamic Arab society, and also no organized judicial system. =^=

“However, if disputes arose concerning rights of property, succession, and torts other than homicide, they were not normally decided by self-help but, if negotiation between the parties was unsuccessful, by recourse to an arbitrator. Because one of the essential qualifications of an arbitrator was that he should possess supernatural powers, arbitrators were most frequently chosen from among soothsayers. The decision of the arbitrator was obviously not an enforceable judgment, but a statement of what the customary law was, or ought to be; the function of the arbitrator merged into that of a lawmaker, an authoritative expounder of the normative legal custom or sunna. Transposed into an Islamic context, this concept of sunna was to become one of the most important agents, if not the most important, in the formation of Islamic law, and the 'ulama', the authoritative expounders of the law, became not in theory but in fact the lawmakers of Islam. =^=

Muhammad and Islamic Law

Joseph Schacht wrote in the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”: “Muhammad began his public activity in Mecca as a religious reformer, and in Medina he became the ruler and lawgiver of a new society on a religious basis, a society which was meant, and at once began, to replace and supersede Arabian tribal society. Already in Mecca, Muhammad had had occasion to protest against being regarded as merely another soothsayer by his pagan countrymen, and this brought about, in the early period of Medina, the rejection of arbitration as practised by the pagan Arabs. But when Muhammad was called upon to decide disputes in his own community, he continued to act as an arbitrator, and the Qur'an, in a roughly contemporaneous passage, prescribed the appointment of an arbitrator each from the families of husband and wife in the case of marital disputes. In a single verse only, which again is roughly contemporaneous with the preceding passage, the ancient Arab term for arbitration appears side by side with, and is in fact superseded by, a new Islamic one for a judicial decision: ' But no, by thy Lord, they will not (really) believe until they make thee an arbitrator of what is in dispute between them and and within themselves no dislike of that which thou decidest, and submit with (full) submission' (Sura 4. 65). [Source: Joseph Schacht, “Law and Justice”, from the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”, vol. II, pt. VIII/Chapter 4, beginning with pg. 539, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu =^=]

Mohammed and his wife Aisha freeing the daughter of a tribal chief; From the Siyer-i Nebi

“Here the first verb refers to the arbitrating aspect of Muhammad's activity, and the second, ' to decide ', from which the Arabic term qadi is derived, emphasizes the authoritative character of his decision. This is the first indication of the emergence of a new, Islamic, concept of the administration of justice. Numerous passages in the Qur'an show that this ideal demand was slow to be fulfilled, but Muhammad's position as a prophet, backed in the later stages of his career in Medina by a considerable political and military power, gave him a much greater authority than could be claimed by an arbitrator; he became a 'Prophet-Lawgiver'. But he wielded his almost absolute power not within but without the existing legal system; his authority was not legal but, for the believers, religious, and, for the lukewarm, political. He was essentially a townsman, and the bitterest tirades in the Qur'an are directed against the bedouin. =^=

“Muhammad's legislation, too, was a complete innovation in the law of Arabia. Muh ammad, as a prophet, had little reason to change the existing customary law. His aim was not to establish a new legal order, but to teach men what to do in order to achieve their salvation. This is why Islamic law is a system of duties, of ritual, legal, and moral obligations, all of which are sanctioned by the authority of the same religious command. Thus the Qur'an commands to arbitrate with justice, to give true evidence, to fulfil one's contracts, and, especially, to return a trust or deposit to its owner. As regards the law of family, which is fairly exhaustively treated in the Qur'an, the main emphasis is laid on how one should act towards women and children, orphans and relatives, dependants and slaves. In the field of penal law, it is easy to understand that the Qur'an laid down sanctions for transgressions, but again they are essentially moral and only incidentally penal, so much so that the Qur'an prohibited wine-drinking but did not enact any penalty, and the penalty was determined only at a later stage of Ishmic law. The reasons for Qur'anic legislation on all these matters were, in the firs tplace, the desire to improve the position of women, of orphans and of the weak in general, to restrict the laxity of sexual morals and to strengthen the marriage tie, to restrict private vengeance and retaliation and to eliminate blood feuds altogether; the prohibition of gambling, of drinking wine and of taking interest are directly aimed at ancient Arabian standards of behaviour. =^=

“The main political aim of the Prophet, the dissolution of the ancient bedouin tribal organization and the creation of an essentially urban community of believers in its stead, gave rise to new problems in family law, in the law of retaliation and in the law of war, and these had to be dealt with. The encouragement of polygamy by the Qur'an is a case in point. A similar need seems to have called for extensive modifications of the ancient law of inheritance, the broad outlines of which were, however, preserved; here, too, the underlying tendency of the Qur'anic legislation was to favour the underprivileged; it started with enunciating ethical principles which the testators ought to follow, and even in its final stage, when fixed shares in the inheritance were allotted to persons previously excluded from succession, the element of moral exhortation had not disappeared. This feature of Qur'anic legislation was preserved by Islamic law, and the purely legal attitude, which attaches legal consequences to relevant acts, is often superseded by the tendency to impose ethical standards on the believer. =^=

Early Islamic Law

Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr. Wrote in “A Concise History of the Middle East”: “The first Muslims based their ideas of right and wrong on the customary norms of the society they knew, that of western Arabia. Caravan traders had worked out elaborate rules about commercial transactions and property rights, while criminal law still held to the principles of retribution based on the tribal virtues (the muruwwah). Muhammad's mission broadened and strengthened the realm of rights and responsibilities. The Quran spelled out many points, and Muhammad's precepts and practices (what later Muslims would call his sunnah) fixed some of the laws of the nascent ummah. After the Prophet died, his survivors tried to pattern their lives on what he had said or done, and on what he had told them to do or not to do. Muhammad's companions, especially the first four caliphs, became role models to the Muslims who came later; indeed, their practices were the sunnah for the caliphs and governors who followed them. Gradually, the traditional norms of Arabia took on an Islamic pattern, as the companions inculcated the values of the Quran and the sunnah in their children and instructed the new converts to Islam. Even after the men and women who had known Muhammad died out, the dos and don'ts of Islam were passed down by word of mouth for another century. /~\

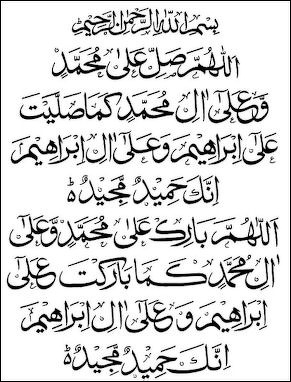

darood ("Blessings of Allah be upon him and his household and peace")

Charles F. Gallagher wrote in “International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences”: During this formative period the administration of justice was carried out somewhat haphazardly by Qur’anic precepts as they were customarily interpreted by the Arabs, and with the incorporation of some elements of Roman and pre-Islamic law, administrative procedures were modified and more fully incorporated in the embryonic body of legal practice. Toward the end of the Umayyad period, between about A.D. 725 and 750, the Qur’an and the sunnah had become established as the principal sources of Muslim jurisprudence, but there had also grown up a body of jurists and men interested in legal problems who in their experience were finding it necessary to go beyond these sources to devise laws for the community.[Source: Charles F. Gallagher, “International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences”, 1960s, Encyclopedia.com]

Up to this time law and religion were inextricably interconnected and rested upon the infallible revelation of the Qur’an and its presumably infallible verification in detail by the tradition. The infallibility of these two sources, however, was not of the same order; in fact, the proliferation of narratives in the tradition was such that scholars were aware that many of them were spurious. In order to establish the veracity of the tradition beyond any doubt and reinforce its position as an anchor of the legal system, a science of hadith criticism was introduced in the second and third centuries A.H. This placed stress on the reliability of each member of the chain of authorities cited.

Biographies of transmitters were compiled and their subjects carefully investigated, after which each narrative (hadith) was classified for legal purposes as sound, good, or weak. Many traditions that modern Western scholarship considers highly dubious were classified as sound in this process, for many theologians were at bottom less interested in the historical objectivities of a given tradition than in the practical consequences of its acceptance and application to community life. Later, in the ninth century A.D., hadith study developed into a full-fledged scholastic enterprise; the great compilations of al-Bukhari (d. 870) and Muslim (d. 875) have enjoyed almost universal authority in Islam.

Early Development of Islamic Law

Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr. wrote; After the Prophet died, his survivors tried to pattern their lives on what he had said or done, and on what he had told them to do or not to do. Muhammad's companions, especially the first four caliphs, became role models to the Muslims who came later; indeed, their practices were the sunnah for the caliphs and governors who followed them. Gradually, the traditional norms of Arabia took on an Islamic pattern, as the companions inculcated the values of the Quran and the sunnah in their children and instructed the new converts to Islam. Even after the men and women who had known Muhammad died out, the dos and don'ts of Islam were passed down by word of mouth for another century. /~\

“Because of the Arab conquests, the early Muslims picked up many concepts and institutions of Roman and Persian law. Quran reciters and Muhammad's companions gradually gave way to arbiters and judges who knew the laws and procedures of more established empires. As the ummah grew and more arguments arose about people's rights and obligations within this hybrid system, the leaders and the public realized that the laws of Islam must be made clear, uniform, organized, acceptable to most Muslims, and thereby enforceable. By the time the Abbasids took power in 750, Muslims were starting to study the meaning of the Quran, the life of Muhammad and the sayings and actions ascribed to him by those who had known him. A specifically Islamic science of right versus wrong, or jurisprudence, thus evolved. Its Arabic name, fiqh, originally meant "learning," and even now a close relation exists in the Muslim mind between fuqaha (experts on the Shari'ah) and the ulama (the Muslim religious scholars, or literally "those who know").” /~\

Joseph Schacht wrote in the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”: “Islamic law as we know it today cannot be said to have existed as yet in the time of Muhammad; it came gradually into existence during the first century of Islam. It was during this period that nascent Islamic society created its own legal institutions. The ancient Arab system of arbitration, and Arab customary law in general, continued under the first successors of Muhammad, the caliphs of Medina. In their function as supreme rulers and administrators, the early caliphs acted to a great extent as the lawgivers of the Islamic community; during the whole of this first century the administrative and legislative functions of the Islamic government cannot be separated. But the object of this administrative legislation was not to modify the existing customary law beyond what the Qur'an had done; it was to organize the newly conquered territories for the benefit of the Arabs, and to assure the viability of the enormously expanded Islamic state. [Source: Joseph Schacht, “Law and Justice”, from the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”, vol. II, pt. VIII/Chapter 4, beginning with pg. 539, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu =^=]

Abu Bakr, the First Caliph, stops the Meccan Mob

“The first caliphs did not, for instance, hesitate to repress severely any manifestation of disloyalty, and even to punish with flogging the authors of satirical poems directed against rival tribes, a recognized form of poetic expression which, however, might have threatened the internal security of the state. This particular decision did not become part of Islamic law, but other enactments of the caliphs of Medina gained official recognition, not as decislons of the caliphs, but because they could be subsumed under oneor the other of the official sources of Islamic law which later theory came to recognize. The introduction of stoning to death as a punishment for unchastity under certain conditions is one such enactment. In the theory of Islamic law, its authority derives from alleged commands of the Prophet; there also exists an alleged verse of the Qur'an to this effect which, however, does not form part of the official text and must be considered spurious. Traditions reporting alleged acts and sayings of the Prophet came into use as proof-texts in law not earlier than the end of the first century of Islam, and the spurious verse of the Qur'an represents an earlier effort to establish the validity of the penal enactment in question. That the need of this kind of validation was felt at all, shows how exceptional a phenomenon the legislation of Muhammad had been in the eyes of his contemporaries. =^=

“The political schisms which rent the Islamic community when it was still less than forty years old, led to the secession of the two dissident, and later 'heterodox', movements of the Kharijites and of the Shi'a, but they did not lead to significant new developments in Islamic law; the essentials of a system of religious law did not as yet exist and the political theory of the Shi'a, which more than anything else might have been expected to lead to the elaboration of quite a different system of law, was developed only later. In fact, those two groups took over Islamic law from the 'orthodox' or Sunni community as it was being developed there, making only such essentially superficial modifications as were required by their particular political and dogmatic tenets. In one respect, however, the exclusive, and therefore ' sectarian ', character of the two secessionist movements influenced not so much the positive contents as the emphasis and presentation of their doctrines of religious law; the law of the Shi'a is dominated by the concept of taqiyya, 'dissimulation' (a practice which, it is true, was forced upon them by the persecutions which they had to suffer), and by the distinction between esoteric and exoteric doctrines in some of their schools of thought; and that of the Kharijites is dominated by the complementary concepts of walaya, 'solidarity', and bara'a, 'exclusion', 'excommunication'. =^=

Sunna, Precedent or Normative Custom

Umar, the Second Caliph, Sees the Poor Widow

Joseph Schacht wrote in the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”: “At an early period, the ancient Arab idea of sunna, precedent or normative custom, reasserted itself in Islam. Whatever was customary was right and proper, whatever their forefathers had done deserved to be imitated, and in the idea of precedent or sunna the whole conservatism of Arabs found expression. This idea presented a formidable obstacle to every innovation, including Islam itself. But once Islam had prevailed, the old conservatism reasserted itself within the new community, and the idea of sunna became one of the central concepts of Islamic law. [Source: Joseph Schacht, “Law and Justice”, from the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”, vol. II, pt. VIII/Chapter 4, beginning with pg. 539, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu =^=]

“Sunna in its Islamic context originally had a political rather than a legal connotation. The question whether the administrative acts of the First two caliphs, Abu Bakr and 'Umar, should be regarded as binding precedents, arose probably when a successor to 'Umar had to beappointed in 23/644, and the discontent with the policy of the third caliph, 'Uthman, which led to his assassination in 35/655, took the form of a charge that he, in his turn, had diverged from the policy of his predecessors and, implicitly, from the Qur'an. In this connexion, there arose the concept of the 'sunna of the Prophet', not yet identified with any set of positive rules, but providing a doctrinal link between the sunna of Abu Bakr and 'Umar' and the Qur'an. The earliest evidence for this use of the term 'sunna of the Prophet' dates from about 76/695, and we shall see later how it was introduced into the theory of Islamic law. =^=

“The thirty years of the caliphs of Medina later appeared, in the picture that the Muslims formed of their own history, as the golden age of Islam. This is far from having been the case. On the contrary, the period of the caliphs of Medina was rather in the nature of a turbulent interval between the first years of Islam under Muh ammad and the Arab kingdom of the Umayyads. Not even the rulings of the Qur'an were applied without restriction. It can be shown from the development of Islamic legal doctrines that any but the most perfunctory attention given to the Qur'anic norms, and any but the most elementary conclusions drawn from them, belong almost invariably to a secondary and therefore later stage. In several cases the early doctrine of Islamic law is in direct conflict with the clear and explicit wording of the Qur'an. Sura 5.6, for instance, says clearly: ' O you who believe, when you rise up for worship, wash your faces and your hands up to the elbows, and wipe over your heads and your feet up to the ankles'; the law nevertheless insists on washing the feet, and this is harmonized with the text by various means.

Sura 2.282 endorsed the current practice of putting contracts, particularly those which provided for performance in the future, into writing, and this practice did in fact persist in Islam. Islamic law, however, emptied the Qur'anic command of all binding force, denied validity to written documents, and insisted on the evidence of eye-witnesses,in the Qur'anic passage play only a subsidiary part. It is, of course, true that many rules of Islamic law, particularly in the law of family and in the law of inheritance, not to mention worship and ritual, were, in the nature of things, based on the Qur'an and, we must assume, on the example of Muhammad from the very beginning. But even here we notice (as far as we are able to draw conclusions on this early period from the somewhat later doctrines of Islamic law) a regression, in so far as pagan and tribal Arab ideas and attitudes succeeded in overriding the intention, if not the wording, of the Qur'anic legislation. This went parallel to, and was indeed caused by, the exacerbation of tribal attitudes in the turbulence created by the Arab wars of conquest and their success. The Qur'an, in a particular situation, had encouraged polygamy, and this, from being an exception, now became one of the essential features of the Islamic law of marriage. It led to a definite deterioration in the position of married women in society, compared with that which they had enjoyed in pre-Islamic Arabia, and this was only emphasized by the fact that many perfectly respectable sexual relationships of pre-Islamic Arabia had been outlawed by Islam.

Election of Uthman, the Third Caliph

As against tribal pride and exclusiveness, the Qur'an had emphasized the fraternity rather than the equality of all Muslims, nevertheless, social discrimination and Arab pride immediately reasserted themselves in Islam. Non-Arab converts to Islam, whatever their previous social standing, were regarded as second-class citizens (mawali) during the first hundred and fifty years of Islam, and all schools of law had to recognize degrees of social rank which did not amount to impediments to marriage but nevertheless, in certain cases, enabled the interested party to demand the dissolution of the marriage by the qadi. The Qur'an had taken concubinage for granted, but in the main passage concerning it (Sura 4.3) concubinage appears as a less expensive alternative to polygamy, a concept far removed from the practice of unlimited concubinage in addition to polygamy which prevailed as early as the first generation after Muhammad and was sanctioned by all schools of law. Also, the Qur'anic rules concerning repudiation, which had been aimed at safeguarding the interests of the wife, lost much of their value by the way in which they were applied in practice. Early Islamic practice, influenced no doubt by the insecurity which prevailed in the recently founded garrison-cities with their mixed population, extended the seclusion and the veiling of women far beyond what had been envisaged in the Qur'an, but in doing this it merely applied the clearly formulated intention of the Qur'an to new conditions. Taking these modifications into account, the pre-Islamic structure of the family survived into Islamic law. =^=

“During the greater part of the first/seventh century, Islamic law, in the technical meaning of the term, did not as yet exist. As had been the case in the time of Muhammad, law as such fell outside the sphere of religion; if no religious or moral objections were involved, the technical aspects of law were a matter of indifference to the Muslims. This accounts for the widespread adoption, or rather survival, of certain legal and administrative institutions and practices of the conquered territories, such as the treatment of the tolerated religions which was closely modelled on the treatment of the Jews in the Byzantine empire, methods of taxation, the institution ofemphyteusis, and so forth. The principle of the retention of pre-Islamic legal practices under Islam was sometimes openly acknowledged, e.g. by the historian al-Baladhuri (d. 279/892), but generally speaking fictitious Islamic precedents were later invented as a justification. =^=

“The acceptance of foreign legal concepts and maxims, extending to methods of reasoning and even to fundamental ideas of legal science, however, demands a more specific explanation. Here the intermediaries were the cultured converts to Islam. During the first two centuries of the Hijra, these converts belonged mainly to the higher social classes, they were the only ones to whom admission to Islamic society, even as second-class citizens, promised considerable advantages, and they were the people who (or whose fathers) had enjoyed a liberal education, that is to say, an education in Hellenistic rhetoric, which was the normal one in the countries of the Near East which the Arabs had conquered. This education invariably led to some acquaintance with the rudiments of law. The educated converts brought their familiar ideas with them into their new religion. In fact, the concepts and maxims in question were of that general kind which would be familiar not only to lawyers but to all educated persons. In this way, elements originating from Roman and Byzantine law, from the canon law of the Eastern Churches, from Talmudic and rabbinic law, and from Sassanid law, infiltrated into the nascent religious law of Islam during its period of incubation, to appear in the doctrines of the second/eighth century. =^=

Development of Islamic Law

Islamic law evolved between the eighth and tenth centuries. Because Islam has no ordained priesthood, direction of the Muslim community rests on the learning of religious scholars (ulama) who are expert in understanding the Quran and its appended body of commentaries. Islamic scholars reputed for their knowledge of the Qur’an, hadiths, and sunna were accepted as authoritative interpreters of seriat . Several of them compiled texts of case law that formed the basis of legal schools. Eventually, Sunni Muslims came to accept four schools of law as equally valid.[Source: Library of Congress *]

Islamic law has it roots in the laws and rules laid out in the Qur’an. These were first supplemented with rules, interpretations and insights offered by early Caliphs and governors who drew on Arab traditions and their own experience and judgements and by Muslim scholars who gave various issues a great deal of study, discussion and thought. The drive to create a Muslim legal system began when groups of students of the Qur’an in major cities who felt these laws and rules needed to be codified.

Islamic law was originally not developed just for Muslims it was developed for all of mankind. It was regarded as the word of god and thus had to be universally and absolutely followed by everyone. The basic foundation of Sharia, argued by the pioneering jurist al-Shafi’i (died 820), is that the laws of the Qur’an and laws with direct eye-witness links to Muhammad would have precedence over all other laws.

Development of Sharia Schools

Hanbali fiqh books

By the end of the eighth century, four main schools of Muslim jurisprudence had emerged in Sunni Islam to interpret the sharia (Islamic law). Prominent among these groups was the Hanafi school and the Shafii school. Because Islam has no ordained priesthood, direction of the Muslim community rests on the learning of religious scholars (ulama) who are expert in understanding the Quran and its appended body of commentaries. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Eventually, Sunni Muslims came to accept four schools of law as equally valid. Two schools of seriat exist in contemporary Turkey: the Hanafi, founded by Iraqi theologian Abu Hanifa (ca. 700-67), and the Shafii, founded by the Meccan jurist Muhammad ash Shafii (767-820). Most Muslim Turks follow the Hanafi school, whereas most Sunni Kurds follow the Shafii school. *

During the first centuries of Islam there were hundred schools of Islamic law. Some were influenced by Roman law and Greek-style speculative reasoning, which alarmed conservatives and divided the community and triggered a movement to unify the Muslim community and reduce the number of schools.

The problem of dealing with so many schools was a weeding out process and popularity contest influenced by group politics, fashion, trends, ideas and political and religious support and respect and authority that certain schools had at certain times. Over time certain schools fell out of favor and lost adherents while other schools gained favored and won adherents; minor schools were squeezed and large ones grew into orthodox, established institutions.

See Separate Article: FOUR SCHOOLS OF SUNNI SHARIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Ijma (Consensus of the Community)

Imam al-Sadiq

The problem of dealing with doctrinal disputes was dealt with within the schools through the “Consensus of the Community" (ijma), based on the principal that the “Community will never agree upon an error." Rulings within each school were unified and consolidated by a particular ijma . Each school recognized the ruling that were acceptable and authoritative with the system of that school.

Charles F. Gallagher wrote in “International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences”: The construction of the Muslim legal edifice was completed by the introduction of the principle of consensus (ijmda‘) as the guarantor of legal theory and beyond that of the integrity of the entire frame-work of Muslim religious thought. The doctrine of ijma‘ has been subsumed in a tradition that relates the saying of Muhammad, “My community will not agree in error.” During the second century A.H. it had been established that the consensus of the community, which meant that of the jurists and scholars dealing with religious and legal matters, was binding. The extension of this concept by these very jurists, to stamp with approval the legal systems they had elaborated, removed the possibility of a revision of their work by later generations and gave final validity to the entire structure. Ijma‘ verifies the authenticity and the proper interpretation of the Qur’an; it guarantees the correct transmission of the sunnah tradition and the proper use of qiyas. It covers all aspects of the holy law and admits the validity of distinctions between the orthodox legal schools. [Source: Charles F. Gallagher, “International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences”, 1960s, Encyclopedia.com]

Of the highest importance, however, is the fact that consensus itself becomes, as Gibb has noted, “a third channel of revelation” and is elevated to infallibility itself alongside the Qur’an and the sunnah, which it sanctions. While it is often suggested that the principle of consensus was adopted as a device of convenience by the legal scholars, a broader view leads to the conclusion that the Muslim community’s sense of its own divinely instituted and rightly guided nature has always been so highly developed that it produced an unwavering belief in its own charisma and infallibility. The ideal of Islamic law taken as a whole is absolutist and charismatic at its roots and may be considered a reflection of the Islam which Muslims have brought into being, either, as they would believe, through their unerring understanding of God’s word or, as Western scholars believe, through their own will and actions.

Development of Islamic Law Under the Umayyads

Joseph Schacht wrote in the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”: “The rule of the caliphs of Medina was supplanted by that of the Umayyads in 4I/66I. The Umayyads and their governors were responsible for developing a number of the essential features of Islamic worship and ritual. Their main concern, it is true, was not with religion and religious law, but with political administration, and here they represented the centralizing and increasingly bureaucratic tendency of an orderly adrninistration as against bedouin individualism and the anarchy of the Arab way of life. Both Islamic religious ideals and Umayyad administration co-operated in creating a new framework for Arab Muslim society. In many respects Umayyad rule represents the consummation, after the turbulent interval of the caliphate of Medina, of tendencies which were inherent in the nature of the community of Muslims under Muhammad. It was the period of incubation of Islamic civilization and, within it, of the religious law of Islam. [Source: Joseph Schacht, “Law and Justice”, from the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”, vol. II, pt. VIII/Chapter 4, beginning with pg. 539, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu =^=]

“The administration of the Umayyads concentrated on waging war against the Byzantines and other external enemies, on assuring the internal security of the state, and on collecting revenue from the subject populations and paying subventions in money or in kind to the Arab beneficiaries. We therefore find evidence of Umayyad regulations or administrative law mainly in the helds of the law of war and of fiscal law. All this covered essentially the same ground as the administrative legislation of the caliphs of Medina, but the social background was sensibly different. The Umayyads did not interfere with the working of retaliation as it had been regulated by the Qur'an, but they tried to prevent the recurrence of Arab tribal feuds and assumed the accountancy for payments of blood-money, which were effected in connexion with the payment of subventions. On the other hand, they supervised the application of the purely Islamic penalties, not always in strict conformity with the rules laid down in the Qur'an. =^=

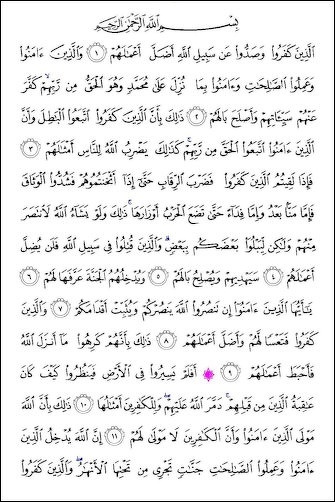

Sura 47

“The Umayyads, or rather their governors, also took the important step of appointing Islamic judges or qadis. The offlce of qadi was created in and for the new Islamic society which came into being, under the new conditions resulting from the Arab conquest, in the urban centres of the Arab kingdom. For this new society, the arbitration of pre-Islamic Arabia and of the earliest period of Islam was no longer adequate, and the Arab arbitrator was superseded by the Islamic qadi. It was only natural for the qadi to take over the seat and wand of the arbitrator, but, in contrast with the latter, the qadi was a delegate of the governor. The governor, within the limits set for him by the caliph, had full authority over his province, administrative, legislative, and judicial, without any conscious distinction of functions; and he could, and in fact regularly did, delegate his judicial authority to his 'legal secretary', the qadi. The governor retained, however, the power of reserving for his own decision any lawsuit he wished, and, of course, of dismissing his qadi at will.

The contemporary Christian author, John of Damascus, refers to these governors and their delegates, the qadis, as the lawgivers of Islam. By their decisions, the earliest Islamic qadis, did indeed lay the basic foundations of what was to become Islamic law. They gave judgment according to their own discretion or ' sound opinion' (ra'y), basing themselves on customary practice which in the nature of things incorporated administrative regulations, and taking the letter and the spirit of the Qur'anic regulations and other recognized Islamic religious norms into account as much as they thought fit. Whereas the legal subject-matter had not as yet been islamized to any great extent beyond the stage reached in the Qur'an, the office of qadi itself was an Islamic institution typical of the Umayyad period, in which care for elementary administrative efficiency and the tendency to islamize went hand in hand. The subsequent development of Islamic law, however, brought it about that the part played by the earliest qadi in creating it did not achieve recognition in the legal theory which finally prevailed. =^=

“The jurisdiction of the qadi extended to Muslims only; the non-Muslim subject populations retained their own traditional legal institutions, including the ecclesiastical and rabbinical tribunals, which in the last few centuries before the Arab conquest had to a great extent duplicated the judicial organization of the Byzantine state. This is the basis of the factual legal autonomy of the non-Muslims which was extensive in the Middle Ages, and has survived in part down to the present generation. The Byzantine magistrates themselves had left the lost provinces at the time of the conquest, but an office of local administration, the functions of which were partly judicial, was adopted by the Muslims: the office of the 'inspector of the market' or agoranome, of which the Arabic designation 'amil al-suq or sahib al-suq is a literal translation. In the last few centuries before the Muslim conquest this office had lost its originally high status, but had remained a popular institution among the settled populations of the Near East. Later, under the early 'Abbasids, it developed into the Islamic office of the mutasib. Similarly, the Muslims took over the office of the ' clerk of the court' from the Sassanid administration. =^=

Development of Islamic Law Under the Abbasids

Joseph Schacht wrote in the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”: “When the Umayyads were overthrown by the 'Abbasids in I32/750, Islamic law, though still in its formative stage, had acquired its essential features; the need of Arab Muslim society for a new legal system had been filled. The early 'Abbasids continued and reinforced the islamizing trend which had become more and more noticeable under the later Umayyads. For reasons of dynastic policy, and in order to differentiate themselves from their predecessors, the 'Abbasids posed as the protagonists of Islam, attracted specialists in religious law to their court, consultet them on problems within their competence, and set out to translate their doctrines into practice. But this effort was shortlived. The early specialists who had formulated their doctrine not on the basis of, but in a certain opposition to, Umayyad popular and administrative practice, had been ahead of realities, and now the early 'Abbasids and their religious advisers were unable to carry the whole of society with them. [Source: Joseph Schacht, “Law and Justice”, from the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”, vol. II, pt. VIII/Chapter 4, beginning with pg. 539, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu =^=]

Islamic organizational chart, Muamalat

“This double-sided effect of the 'Abbasid revolution shows itself clearly in the development of the office of qadi. The qadi was not any more the legal secretary of the governor; he was normally appointed by the caliph, and until relieved of his office, he must apply nothing but the sacred law, without interference from the government. But theoretically independent though they were, the qddis had to rely on the political authorities for the execution of their judgments, and being bound by the formal rules of the Islamic law of evidence, their inability to deal with criminal cases became apparent. (Under the Umayyads, they or the governors themselves had exercised whatever criminal justice came within their competence.) Therefore the administration of the greater part of criminal justice was taken over by the police, and it remained outside the sphere of practical application of Islamic law. The centralizing tendency of the early 'Abbasids also led, perhaps under the influence of a feature of Sassanid administration, to the creation of the office of chief qadi. It was originally an honoriflc title given to the qadi of the capital, but the chief qadi soon became one of the most important counsellors of the caliph, and the appointment and dismissal of the other qadis, under the authority of the caliph, became the main function of his office. =^=

See Separate Article: ISLAMIC LAW DURING THE ABBASID PERIOD (A.D. 750 TO 1258) africame.factsanddetails.com

Later Developments in Islamic Law

Joseph Schacht wrote in the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”: “The Ottoman empire in the sixteenth century is characterized by strenuous efforts on the part of the sultans to translate Islamic law in its Hanafi form into actual practice; this was accompanied by the enactment of qanun-name which, though professing merely to supplement Islamic law, in fact superseded it. On the part of the representatives of law we find, naturally enough, uncompromising rejection of everything that went against the letter of religious law, but at the same time unquestioning acceptance of the directives of the sultans concerning its administration, and, on the part of the chief muftis, a distinctive eagerness to harmonize the rules of the Shari'a with the administrative practice of the Ottoman state. A parallel effort in the Mughal empire in the seventeenth century was part of the orthodox reaction against the emphemeral religious experiment of the emperor Akbar. In the Persia of the Safavids, the religious institution, including the scholars and qadis, was controlled by the sadr, who exercised control over it on behalf of the political institution, thereby reducing the importance of the qadis. The Safavids' supervision of the religious institution was more thorough than had been that of the preceding Sunni rulers, and by the second half of the eleventh/seventeenth century the subordination of the religious institution to the political was officially recognized. This whole development had already begun under the later Timurids. [Source: Joseph Schacht, “Law and Justice”, from the “Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Islam”, vol. II, pt. VIII/Chapter 4, beginning with pg. 539, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu =^=]

Aqabozorg The 19th century saw the emergence of new Civil Courts and the relegation of Sharia to mostly family law. This process was accelerated in the 20th century and some Muslim countries such as Turkey got rid of Sharia altogether. In the civil courts and in some of the Islamic courts laws based on new legislation were introduced and other matters were addressed with laws based on new interpretations of Islamic scriptures and traditions and were not bound to any one particular Islamic legal school and included Sunni and Shia interpretations.

Some interpretations — such as limiting polygamy and giving women the rights in divorce — contradicted or went again the spirit of the Qur’an . Many of the new laws and interpretations were made by the ruling elite and were influenced by colonialism and West legal concept. Some of the decisions not only went against Islam but also undermined the spirit of the ijma (the Muslim community).

Asifa Quraishi-Landes wrote in the Washington Post: “In most Muslim countries modern laws have been introduced for almost all matters except for family law — mostly laws governing women and children — in which Sharia is used. Moderate Muslim states apply Sharia to family and religious law but not criminal, legal and state matters. Among 49 Muslim nations only Iran and Saudi Arabia follow Sharia law in its strictest sense. Afghanistan used to when it was ruled by the Taliban. Sharia is said to be applied behind close doors even in secular countries like Canada. Since the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and the Islamic revival the reintroduction of Sharia and to what degree has been a major issue in many Muslim countries. [Source: Asifa Quraishi-Landes, Washington Post, June 24, 2016]

Merging of Sharia and Western Law

Asifa Quraishi-Landes wrote in the Washington Post: “While it’s true that sharia influences the legal codes in most Muslim-majority countries, those codes have been shaped by a lot of things, including, most powerfully, European colonialism. France, England and others imposed nation-state models on nearly every Muslim-majority land, inadvertently joining the crown and the faith. In pre-modern Muslim lands, fiqh authority was separate from the governing authority, or siyasa. Colonialism centralized law with the state, a system that carried over when these countries regained independence. [Source: Asifa Quraishi-Landes, Washington Post, June 24, 2016 ~~]

“When Muslim political movements, such as Jamaat-e-Islami in Pakistan or the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, have looked to codify sharia in their countries, they have done so without any attention to the classical separation of fiqh and siyasa, instead continuing the legal centralization of the European nation-state. That’s why these movements look to legislate sharia — they want centralized laws for everything. But by using state power to force particular religious doctrines upon the public, they would essentially create Muslim theocracies, contrary to what existed for most of Muslim history.” ~~

In 1956, Sudan became the first sub-Saharan African country to gain independence from the British. Mark Fathi Massoud wrote: “ In the national archives and libraries of the Sudanese capital Khartoum, and in interviews with Sudanese lawyers and officials, I discovered that leading judges, politicians and intellectuals actually pushed for Sudan to become a democratic Islamic state. They envisioned a progressive legal system consistent with Islamic faith principles, one where all citizens — irrespective of religion, race or ethnicity — could practice their religious beliefs freely and openly. “The People are equal like the teeth of a comb,” wrote Sudan’s soon-to-be Supreme Court Justice Hassan Muddathir in 1956, quoting the Prophet Muhammad, in an official memorandum I found archived in Khartoum’s Sudan Library. “An Arab is no better than a Persian, and the White is no better than the Black.” Sudan’s post-colonial leadership, however, rejected those calls. They chose to keep the English common law tradition as the law of the land. [Source: Mark Fathi Massoud, Director of Legal Studies and Associate Professor of Politics, University of California, Santa Cruz, The Conversation, December 31, 2020]

There are reasons why early Sudan sidelined Sharia: 1) politics, 2) pragmatism and 3) demography. 1) Rivalries between political parties in post-colonial Sudan led to parliamentary stalemate, which made it difficult to pass meaningful legislation. So Sudan simply maintained the colonial laws already on the books. 2) There were practical reasons for maintaining English common law, too. Sudanese judges had been trained by British colonial officials. So they continued to apply English common law principles to the disputes they heard in their courtrooms. Sudan’s founding fathers faced urgent challenges, such as creating the economy, establishing foreign trade and ending civil war. They felt it was simply not sensible to overhaul the rather smooth-running governance system in Khartoum.

3) The continued use of colonial law after independence also reflected Sudan’s ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity. Then, as now, Sudanese citizens spoke many languages and belonged to dozens of ethnic groups. At the time of Sudan’s independence, people practicing Sunni and Sufi traditions of Islam lived largely in northern Sudan. Christianity was an important faith in southern Sudan. Sudan’s diversity of faith communities meant that maintaining a foreign legal system — English common law — was less controversial than choosing whose version of Sharia to adopt.

Sharia Today

Sharia What'sApp

Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr. Wrote in “A Concise History of the Middle East”: “But is the Shari'ah relevant today? The laws are immobile, critics claim, and cannot set the norms for human behavior in a rapidly changing world. Even in the period we have studied so far, strong rulers tried to bypass certain aspects of the Shari'ah, perhaps by a clever dodge, more often by issuing secular laws, or qanuns. The ulama, as guardians of the Shari'ah, had no police force with which to punish such a ruler. But they could stir up public opinion, even to the point of rebellion. No ruler would have dared to change the five pillars of Islam and, until recently, none interfered with laws governing marriage, inheritance, and other aspects of personal status. [Source: Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr., “A Concise History of the Middle East,” Chapter. 8: Islamic Civilization, 1979, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu /~]

“Islam today must deal with the same problem facing Orthodox Judaism: How can a religion based on adherence to a divinely sanctioned code of conduct survive in a world in which many of its nation-states and leading minds no longer believe in God -- or at any rate act as if they do not? Perhaps the time will come when practicing Muslims, Christians, and Jews will settle their differences -- even the Arab-lsraeli conflict -- in order to wage war on their common enemies: secularism, positivism, hedonism, and the various ideologies that have arisen in modern times. /~\

“What parts of the Shari'ah are irrelevant? Are the marriages contracted by young people for themselves more stable than those arranged for them by their parents? Has the growing frequency of fornication and adultery in the West strengthened or weakened the institution of the family? If the family is not to be maintained, in what environment should children be nurtured and taught how to act like men or women? Has the blurring of sex roles in modern society increased or decreased the happiness and security of men and women? Should the drinking of intoxicating beverages be allowed, let alone encouraged, when alcoholism is a major public health problem in most industrialized countries today? Does lending money at interest encourage or inhibit capital formation? Do gambling and other games of chance enrich or impoverish most of the people who engage in them? If the appeal to jihad in defense of Islam seems aggressive, in the name of what beliefs have the most destructive wars of this century been fought? Would Muslims lead better lives if they ceased to pray, fast in Ramadan, pay zakat, and make the hajj to Mecca? These are just some of the questions that must be answered by people who claim that Islam and its laws are anachronistic.” /~\

John L. Esposito wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”: In the contemporary era emphasis on Islam's message of social justice by Islamic movements, both moderate and militant, has been particularly powerful in gaining adherents from poorer and less advantaged groups in such countries as Algeria and Indonesia. In Israel and Palestine, and in Lebanon, groups like Hamas and Hezbollah devote substantial resources to social welfare activities and call for the empowerment of the poor and weak. They teach that social justice can be achieved only if the poor rise up against their oppressive conditions. [Source: John L. Esposito “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, Encyclopedia.com, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024