Home | Category: Pre-Islamic Arabian and Middle Eastern History / Pre-Islamic Arabia / Pre-Islamic Arabian and Middle Eastern History

FRANKINCENSE

frankincence Cultivated from a desert tree that grows in wadis, frankincense is an aromatic gum used in making incense, natural medicines and as base for amouage perfumes. It was valued by the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans to make incense and fragrances used in burials, sacrifices and important rituals. Frankincense is produced in present-day Oman, Yemen, Ethiopia and northern Somalia. [Source: Thomas Abercrombie, National Geographic, October 1985; David Roberts, Smithsonian]

JoAnna Klein wrote in the New York Times: “For thousands of years, cultures around the world have revered the sweet aroma of frankincense. In Ancient Egypt, embalmers stuffed it inside the bodies and tombs of pharaohs and queens and its ashes were ground into eyeliner. Religious texts say rabbis burned it as offerings in Jerusalem’s temples, the three biblical Magi gifted it to the newborn Jesus Christ and the Prophet Muhammad prescribed it for fumigating houses and treating numerous ailments. It was also a staple in ancient Chinese medicine. Today its smoke still permeates centers of worship and Ethiopian coffee ceremonies. [Source: JoAnna Klein, New York Times, July 5, 2019]

Pure frankincense comes in the form of pale, yellow, translucent, gummy blobs. It has a natural oil content, which means that it burns well. A number of medicinal qualities have been ascribed to it. At spice and perfume shops in modern Omani markets pebble-like clumps frankincense are sold in baskets. Buyers often hold the clumps up to the light. They more light that penetrates it the better quality.

When dried and burned, frankincense sap produces a fragrant smoke which has perfumed churches and mosques around the world for centuries. Frankincense produces musky, lemony smoke. It has traditionally been burned on the top of coals in censors made of ceramic or stone. Saudi ones are made of wood and decorated with mirrors. Modern electric ones from Taiwan are made of aluminum and come with a chord.

In the Arab world, frankincense is burned to scent clothes and rooms and ward off evil spirits. As a parting gesture at parties and gatherings burning frankincense is passed around so men can douse their beards in the smoke and women do the same with their hair. Describing the burning of freshly harvested frankincense, Ashon Molavi wrote in Business Week: “Mohammed flicks a lighter and touches the frankincense with flame. There is a sizzling sound, and pale smoke dances and disappears. Mohammed fans the smoke toward me and urges me to run it through my hair.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Gold, Frankincense, Myrrh, And Spiritual Gifts Of The Magi” by Winston James Head Amazon.com ;

“Frankincense & Myrrh: Through the Ages, and a complete guide to their use in herbalism and aromatherapy today” by Martin Watt and Wanda Sellar Amazon.com ;

“Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam” by Robert G. Hoyland Amazon.com ;

“Pre-Islamic Arabia: Societies, Politics, Cults and Identities during Late Antiquity”

by Valentina A. Grasso Amazon.com ;

“Inscriptional Evidence of Pre-Islamic Classical Arabic: Selected Readings in the Nabataean, Musnad, and Akkadian Inscriptions” by Saad D Abulhab Amazon.com ;

“The Ancient Near East: A Very Short Introduction” by Amanda H. Podany, Fajer Al-Kaisi, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East”

by Amanda H. Podany a Amazon.com ;

“The Nabataeans: Builders Of Petra” by Dan Gibson Amazon.com ;

“Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans” by Jane Taylor Amazon.com ;

”History of the Arab People” by Albert Hourani(1991) Amazon.com ;

"Arabian Sands” (Penguin Classics) by Wilfred Thesiger Amazon.com

Frankincense Trees

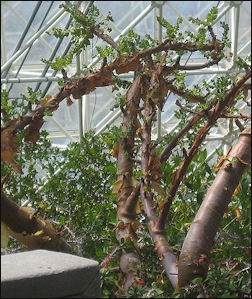

Boswellia tree Frankincense, or olibanum comes from boswellia, a genus of trees and shrubs endemic to the Horn of Africa, Arabian Peninsula and parts of India. boswellia papyrifera, which grows in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan and Darfur, is the species responsible for most of the world’s frankincense. According to the New York Times: When frankincense tappers make gashes into some species of mature boswellia’s woody skin, sap seeps out like blood from a wound. It dries into a scab of resin, which is harvested and sold raw, or turned into oil or incense. [Source: JoAnna Klein, New York Times, July 5, 2019]

Several species of the trees of the genus “Boswellia” yield frankincense. Growing wild in wadis and dry gravel beds, the varities found in Oman and Yemen are stumpy trees that sometimes look like large tumbleweeds with a thick trunk and branches. They reach a height of about eight feet and branches out to a width about equal to its height. The branches flower in September.

Some of the best frankincense grows on a desert plateau that borders the green Qara mountains of the Dhofar region of southern Oman. This area has the right combination of high humidity, white limestones soils, higher winter temperatures, steady tropical sun, and heavy dew from the monsoons. The mountains and escarpments along the coast block the monsoon rains and produce a microclimate where frankincense trees grow. Frankincense groves are often located in places known only to the men who harvest them. Some of the groves are two-day walks along difficult foot trails.

Harvesting Frankincense

The fragrant oil of frankincense trees is harvested like rubber by cutting the bark and letting the resin ooze out. When the resin hardens into crystals it is collected with a scraping knife usually once in the spring. About half a kilogram is taken each time from each tree.

Describing the harvesting of frankincense in Oman, Thomas Abercrombie wrote in National Geographic, "With a few deft strokes of his spatula-like chisel, Haj Mahana bin Saleim chipped away the gray, papery outer bark, smoothing a patch the size of his hand. Magically, milk white tears welled in the green wound. The old Bedouin began scraping another branch. With his bowl he moved from tree to tree, pursuing a harvest unchanged for thousands of years. At some trees, tapped three weeks earlier, Haj Mahana collected handfuls of precious ooze, now harden to a translucent golden hue: pure frankincense." Haj Mahana told National Geographic, "We throw away the first scrapings. A second cutting weeks later gives low quality. Only the third cutting produces real frankincense.”

frankinsence In Dhofar Oman Reporting from Erigavo, Somalia, Jason Patinkin of Associated Press wrote; In a tradition dating to Biblical times, men rise at dawn in the rugged Cal Madow mountains of Somaliland in the Horn of Africa to scale rocky outcrops in search of the prized sap of wild frankincense trees. Bracing against high winds, Musse Ismail Hassan climbs with his feet wrapped in cloth to protect against the sticky resin. With a metal scraper, he chips off bark and the tree's white sap bleeds into the salty air. "My father and grandfather were both doing this job," said Hassan, who like all around here is Muslim. "We heard that it was with Jesus." [Source: Jason Patinkin, Associated Press, December 24, 2016]

“The Cal Madow mountains, which rise from the Gulf of Aden in sheer cliff faces reaching over 8,000 feet (2,440 meters), are part of Somaliland, an autonomous republic in Somalia's northwest. Harvesting frankincense is risky. The trees can grow high on cliff edges, shallow roots gripping bare rock slithering with venomous snakes. Harvesters often slip and tumble down canyon walls. "Every year people either break both legs or die. Those casualties are so often," said Hassan, adding that he wished he had proper ropes and climbing gear. "It's a very dangerous job, but we don't have any alternative." Once the resin is collected, women sort the chunks by color and size. The various classes of resin are shipped to Yemen, Saudi Arabia and eventually Europe and America.

Frankincense Village in Somililand

Mary Harper of the BBC wrote: A little further up the hill is a frankincense village where the trees have been passed down from generation to generation. A woman sat on a turquoise plastic chair in her porch surrounded by children, their mothers and baby goats. "I have no idea what you're talking about," said Racwi Mohamed Mahamud when I asked her about the story of the Magi bearing gifts. "All I know is that my family has owned these trees for hundreds of years. They are passed from great-great-grandfather to great-grandfather to grandfather to father to son." [Source: Mary Harper, BBC News, Daallo Mountain, January 5, 2023]

She ordered a young man to fetch some frankincense recently tapped from a tree. He came out carrying a cloth bundle, set it on the ground and opened it. The air was filled with a delicious woody perfume. We sifted through the sticky substance to find nuggets of frankincense. These are cleaned, dried and graded before being sold to middlemen who export them across the world to burn in churches, mosques and synagogues and to create medicine, essential oils, expensive cosmetics and fine perfumes, including Chanel No 5.

myrrh

Ms Mahamud looked at me blankly when I asked her what she thought about her frankincense eventually ending up in fancy department stores promising miracle anti-ageing properties and mysterious, seductive aromas. "That sounds like nonsense to me," she said. "We burn frankincense to chase away flies and mosquitoes. We inhale it to clear colds and we consume it to cure inflammation. That's it."

People young and old strolled about, chatting, drinking tea and complaining about how low frankincense prices made it difficult to make ends meet, especially during this time of high inflation and severe drought. The tappers and graders get very little of the money made from frankincense, with a kilogram selling for between $5 (£4.15) and $9. There have been scandals involving ruthless middlemen and greedy foreign companies. They get slightly more for myrrh which currently sells for $10/kg. Like frankincense, it is a resin tapped from small, thorny trees. It is used to embalm dead bodies and to make perfume, incense and medicine.It is believed to have antiseptic, analgesic and anti-inflammatory qualities and is used in toothpaste, mouthwash and skin salves.

Myrrh

Myrrh is another Arabian aromatic traditionally used as an anointing oil and base for cosmetics and perfumes, medicines, fumigants and cooking ingredient. It was used in royal mummies in ancient Egypt and as an ingredient in sacred ointments used by Jews in the Old Testament. Before his crucifixion Jesus was offered myrrh with wine, which he refused. After his death his body was treated with "a mixture of myrrh and aloes."

Myrrh is a sap-like natural gum or resin that is extracted from cuts in the bark of a number of small, thorny tree species of the genus Commiphora. Myrrh “Commiphora” is a desert tree with bright white bark. At one time it cost three times more than frankincense. Myrrh is produced in South Yemen near Mablaqah Pass.

Myrrh resin has been used for millennia as a perfume, incense, and medicine and was sometimes mixed with wine and ingested. Myrrh is mentioned as a rare perfume with intoxicating qualities in several places in the Old Testament. In Genesis 37:25 the Ishmaelite traders who bought Joseph from Jacob's sons had "camels ... loaded with spices, balm and myrrh". In Exodus 30:23-25 explains that how Moses used 500 shekels of liquid myrrh tas a core ingredient of the sacred anointing oil. [Source: Wikipedia]

Some believe that the myrrh the three wise men carried was the oil used by Jewish high priests to anoint the kings of Israel. Jesus was offered wine and myrrh before the crucifixion (Mark 15:23). According to John's Gospel, Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea brought a 100-pound mixture of myrrh and aloes to wrap Jesus' body (John 19:39). The Gospel of Matthew relates that as Jesus went to the cross, he was given vinegar to drink mingled with gall: and when he had tasted thereof, he would not drink (Matthew 27:34); the Gospel of Mark describes the drink as wine mingled with myrrh (Mark 15:23). Muslims still use incense derived myrrh in their holy sites and use the resin for health purposes.

Frankincense in the Ancient World and the Bible

Nabateen trade routes on which frankincense was carried Babylonians, Sumerians, Assyrians and Persians offered frankincense and other aromatics to their gods. Known as the "perfume of the gods," frankincense was used in ancient Egyptian rites and as a base for perfumes and an ingredient in mummy preservation oils. The first known reference to frankincense is an inscription on the 15th-century B.C. tomb of Queen Hatshepsut. It describes expeditions sent to Punt (probably Somalia) to fetch it.

In the Bible frankincense symbolized divinity and myrrh was associated with death and persecution of Jesus. When the Queen of Sheba made her celebrated visit to Solomon she brought a "a very great retinue, with camels bearing aromatics and very much gold.” Frankincense was brought as gift to baby Jesus by the Three Wise Men.

The Romans and Greeks craved frankincense, which was as valuable as gold. Describing Greece in 450 B.C., when Athens was its peak, Herodotus wrote, "The whole country is scented [with aromatics from Arabia] and exhales an odor marvelously sweet." Herodotus wrote the place where frankincense grew was guarded by flying serpents. Another Greek historian wrote of the people, "many suppose that they are partaking of ambrosia."

One of the main purposes of frankincense was to hide awful smells. The Romans used it as a deodorant and for perfumed cremation rites. Nero reportedly used a year's supply at the funeral for his consort Poppaea. In Roman times, frankincense was widely used to consecrate temples, mask the odor of cremations, make cosmetics and treat illness such as gout and a "broken head" and "malignant ulcers about the seat."

Frankincense Trail

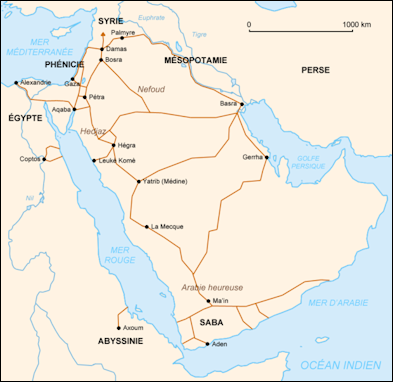

The Nabateans grew rich in part by controlling key choke points of the Frankincense Trail . The Frankincense Trail describes a seaborne and caravan trade route for frankincense and myrrh, linking the places were frankincense was produced in present-day Oman, Yemen, and northern Somalia with markets in the Nile valley, the Fertile Crescent, ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, and India. [Source: Thomas Abercrombie, National Geographic, October 1985; David Roberts, Smithsonian]

Cultivated from a desert tree that grows in wadis, frankincense is an aromatic gum used in making incense, medicines and as base for amouage perfumes. It was valued by the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans to make incense and fragrances used in burials, sacrifices and important rituals.

Some have suggested that frankincense was the first substance to be traded on a worldwide basis. The Frankincense Trail was the basis for the first civilization to grow up on the Arabian peninsula. The languages of the ancient people along the Frankincense Trail is largely undeciphered.

Frankincense was a fabulous source of wealth to those who grew it and were involved in trading it from 1000 B.C. to A.D. 700. There was a certain mystery as to where it came from as well as stories of terrible things happening to people who tried to find where it came from.

See Separate Article: FRANKINCENSE TRAIL africame.factsanddetails.com

Biblical and Egyptian Frankincense and Myrrh in Somaliland?

Mary Harper of the BBC wrote: I met Aden Hassan Salah on Daallo Mountain, part of the Golis range that straddles the self-declared republic of Somaliland and Puntland State in Somalia. Both territories claim the area. "The gold, frankincense and myrrh brought by the three wise men to baby Jesus definitely came from here," said the old man sitting in the dust under a tree. "The routes of the camel caravans that for centuries transported them from here to the Middle East can be seen from space," he said. [Source: Mary Harper, BBC News, Daallo Mountain, January 5, 2023]

The Bible refers to how these animals carried the gifts to Bethlehem where it is believed that Jesus was born. A younger man, dressed in a sarong and Manchester United football top, sprang up from the ground. His name was Mohamed Said Awid Arale. "As I'm sure you know, 'Puntland' means the 'land of exquisite aromas,'" he said. "One thousand, five hundred years before Jesus was born, Egypt's most powerful female pharaoh, Hatshepsut, made a famous expedition here. She ordered the construction of five boats for the journey, filled them with the three precious substances, and sailed back home.Gold was used to adorn Hatshepsut's body, frankincense was burned in her temples and myrrh was used to mummify her after she died."

Frankincense Today

In the 1990s, only a few tons of frankincense were produced each year in Yemen. Most of it was used in rituals and health remedies. Few people there cultivated frankincense anymore. Once the most valuable material in the world it sold for about $2 a bag in markets in Yemen and farmers made only around $150 from each year's harvest. Cheaper fragrances from India called incense supplied most of the world market.

These days is a strong demand for frankincense and thousands of tons of it are is exported each year. A good portion of this is used in Oman, Yemen and other Arab countries. Yemeni women ward off evil spirits after the birth of a child by burning frankincense An amber-colored powder is taken as remedy for nausea. A white frankincense gum called “shihri” is chewed throughout Arabia and is said to be "good for he teeth and gums" and "helps clear the brain."

In recent years demand has increased in the West. Besides its use as incense, frankincense gum is distilled into oil for use in perfumes, skin lotions, medicine and chewing gum. JoAnna Klein wrote in the New York Times: It’s found in natural medicine stores, spiritual shops, bespoke boutiques and online. Sephora, the big chain beauty store, sells essential oil and expensive perfumes that contain it, like Chanel No. 5. Just down the block from a Sephora in Downtown Brooklyn, Tea Brown, co-owner of a traveling spiritual shop called Tea on Mars, sells bags of the gnarled, golden resin from Somalia. It’s so popular, she says, she has to restock it daily. [Source: JoAnna Klein, New York Times, July 5, 2019]

Frankincense Under Threat

JoAnna Klein wrote in the New York Times: Frankincense may not be around much longer, warns a study published in July 2019 in Nature Sustainability. “The first time I said something about frankincense being under threat, there was panic,” said Frans Bongers, an ecologist at Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands who led the study. “I got a lot of people asking me about it,” including Catholic clergy and top suppliers. But as demand increases, over-exploitation and ecosystem degradation are bringing populations to the brink of collapse. The study’s authors estimate that without new trees to replace the old, half the intact forests — and half the frankincense they produce — will be gone within 20 years. [Source: JoAnna Klein, New York Times, July 5, 2019]

To find out its status, Dr. Bongers and colleagues surveyed boswellia papyrifera in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan and Darfur. The trees were old and dying, and most hadn’t produced a young tree in half a century. Models suggested that with no intervention, populations would collapse. Other Boswellia species face similar threats. “The problem, they found, was more people. They burn forests for agriculture and allow livestock that eat saplings to graze in forests. And increasing demand has incentivized poor tree tappers, who make only a tiny percentage of frankincense profit and rely on it for income, to take as much resin as they can in a short amount of time. That leaves overtapped trees that are weak and vulnerable to pests and early death before a new generation can replace them. Despite adult trees producing plenty of seeds, researchers seldom found any new saplings, let alone newly matured trees. Others are too weak to produce enough quality seeds.

According to Save Frankincense: An initial survey in October 2016, followed by subsequent field analyses in 2017 and 2018, revealed that the frankincense trees in certain areas of the growing region, including parts of the Cal Madow, are in rapid decline due to a wave of factors. During our surveys we saw hundreds of dead and dying trees in a number of locations. In just one location we were told that the village had seen a 75 percent decline in resin production. In another we were told that the harvesters were losing 100-200 trees per year in an area of only 10 square kilometers. Given the low densities at which the trees grow, this is a highly significant level of death. Though we have not yet surveyed the entire growing region, these findings are troubling. If the frankincense forests die, both a unique ecosystem and an African cultural legacy will be lost.

World's Last Wild Frankincense Forests, in Somaliland, Are under Threat

The cliffs near Daalo in the Cal Madow mountains in Somaliland, a breakaway region of Somalia, contain the last wild frankincense forests on Earth. The trees there are under threat as prices rise with the global appetite for essential oils. Overharvesting has trees dying off faster than they can replenish, putting the ancient resin trade at risk [Source: Jason Patinkin, Associated Press, December 24, 2016].

Jason Patinkin of Associated Press wrote: The last intact wild frankincense forests on Earth are under threat as prices have shot up in recent years with the global appetite for essential oils. Overharvesting has led to the trees dying off faster than they can replenish, putting the ancient resin trade at risk. "(Frankincense) is something that is literally given by God to humanity, so if we don't preserve it, if we don't take care of it, if we don't look after it, we will lose that," said Shukri Ismail, Somaliland's minister of environment and rural development.

The frankincense trade is Somaliland's largest source of government revenue after livestock and livestock products, Ismail said. Between 2010 and 2016 prices for raw frankincense shot up from around $1 per kilogram to $5 to $7, said Anjanette DeCarlo, an ecologist and director of Conserve Cal Madow, an environmental group.

Reasons for Frankincense’s Decline

Studies have revealed high mortality rates among wild Boswellai papyrifera in Ethiopia and few new plants replacing them. Beetle infestations, fire and animal grazing all contribute. According to Save Frankincense: The demand for frankincense has risen dramatically in the last 5 years, and consequently the price has gone from around $1/kilo to $6/kilo of good resin. This increase in price, along with an increasing population, has kicked off a scramble to obtain resin. Consequently, we’ve observed the following issues: [Source: Save Frankincense]

Over Harvesting: The majority of frankincense trees we saw were cut far too much for them to be healthy. Traditional knowledge, according to clan elders and chiefs we intervie indicates that the trees should be cut no more than 6-12 times, depending on the size of the tree. Studies from Ethiopia on the closely related tree Boswellia papyrifera indicate that trees should not experience more than 9 cuts (Lemenih and Kassa 2011; Eschete et al. 2012) We observed trees with up to 120 cuts at a time, and routinely observed trees with over 50 cuts. This level of cutting significantly weakens the tree and will eventually kill them.

Traditionally, trees are harvested for only 6 months out of the year and allowed to rest by following a cycle of 2 years of tapping, 1 year of rest. Today, the trees are not rested but are harvested every year. Harvesting must stop when the rainy season starts, as the rain washes away the resin, but if the rains do not come, as they have not in the past few years, the harvesters begin tapping the tree again. This double cycle further stresses the trees.

Bad Technique: In an effort to obtain more resin, some harvesters have also begun cutting trees that are too young. Trees generally do not start being harvested until they are around 40 years. Harvesting immature trees presumably stunts their growth and limits their ability to grow into full productive trees. We observed a number of trees that had been completely stripped of their bark. The stripped bark is sold to Ethiopia for low-grade incense. While this practice might temporarily increase resin production as the tree struggles to defend itself, bark stripping will quickly kill the tree.

Pests and Environmental Factors: Many trees are killed by a combination of natural factors as well. Pests, locally called xare, are a significant source of mortality. These pests are likely wood-boring beetles, which burrow into and kill the trees. Limited water due to drought and changing climate also weakens the tree and limits its ability to produce resin to defend itself. Additionally, trees are often blown over and killed during intense wind storms. Overharvesting also weakens the trees, making them more susceptible to mortality by natural factors.

How Gold Miners Are Destroying Myrrh and Frankincense in Somililand

A gold rush in the mountains of Somaliland, frankincense and myrrh trees grow, which began in the late 2010s has led to the uprooting of frankincense and myrrh trees, some centuries old. Mary Harper of the BBC wrote: Today, one of the gifts brought to baby Jesus, gold, is sowing the seeds of destruction of the other two. "Gold-miners have swarmed into the mountains," said Hassan Ali Dirie who works for the Candlelight environmental organisation. "They cut down all the plants when they clear areas for mining. They damage the roots of the trees when they dig for gold. They block crucial waterways with their plastic bottles and other rubbish," he said.[Source: Mary Harper, BBC News, Daallo Mountain, January 5, 2023]

"Day by day, they are ensuring the slow death of these ancient trees. The first to go are the myrrh trees, which are uprooted when the diggers clear the land for surface mining. "Frankincense trees last a bit longer as they grow on rocks and are destroyed once the miners dig deep into the earth."

Many of goldminers are heavy khat users who us a lot of the money they earn to buy khat. They said the Islamist groups, al-Shabab and the Somali branch of Islamic State, had started to demand taxes from the gold-diggers. The villagers explained how the goldminers came to their area with their shovels and pickaxes. "We stood firm against them," said Ms Mahamud shaking her fist. "We said: 'You have come here for your crude, yellow gold. We have our green gold and nobody can take it away from us.'" The miners ran away and never came back.

Helping Endangered Frankincense

JoAnna Klein wrote in the New York Times: “But it’s not hopeless, Dr. Bonger said. Populations can be restored by planting more trees, ceasing burning and building fences to block livestock. Sustainable tapping regulations should be created, taught and enforced, he added, and international trade limited. Buyers at all levels of the supply chain should emphasize quality and sustainable harvesting over quantity to reduce overtapping. And consumers can continue demanding sustainable, socially conscious products. [Source: JoAnna Klein, New York Times, July 5, 2019]

“Anjanette DeCarlo, an environmentalist at the University of Vermont, study, has worked with frankincense in Somaliland. She suggests empowering landowners and creating plantations to take pressure off forests. Plantations already exist in Oman, and in Somaliland, she has planted nurseries with trees that will soon be available for sponsorship. Saving these rare trees, she said, would also protect their endangered habitat.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024