Home | Category: Pre-Islamic Arabian and Middle Eastern History / Pre-Islamic Arabia / Pre-Islamic Arabian and Middle Eastern History

FRANKINCENSE TRAIL

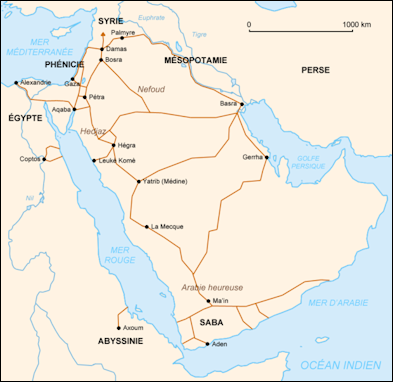

Nabateen trade routes on which frankincense was carried The Frankincense Trail describes a seaborne and caravan trade route for frankincense and myrrh, linking the places were frankincense was produced in present-day Oman, Yemen, and northern Somalia with markets in the Nile valley, the Fertile Crescent, ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, and India. [Source: Thomas Abercrombie, National Geographic, October 1985; David Roberts, Smithsonian]

Cultivated from a desert tree that grows in wadis, frankincense is an aromatic gum used in making incense, medicines and as base for amouage perfumes. It was valued by the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans to make incense and fragrances used in burials, sacrifices and important rituals.

Some have suggested that frankincense was the first substance to be traded on a worldwide basis. The Frankincense Trail was the basis for the first civilization to grow up on the Arabian peninsula. The languages of the ancient people along the Frankincense Trail is largely undeciphered.

Frankincense was a fabulous source of wealth to those who grew it and were involved in trading it from 1000 B.C. to A.D. 700. There was a certain mystery as to where it came from as well as stories of terrible things happening to people who tried to find where it came from.

See Separate Article: FRANKINCENSE AND MYRRH africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Gold, Frankincense, Myrrh, And Spiritual Gifts Of The Magi” by Winston James Head Amazon.com ;

“Frankincense & Myrrh: Through the Ages, and a complete guide to their use in herbalism and aromatherapy today” by Martin Watt and Wanda Sellar Amazon.com ;

“Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam” by Robert G. Hoyland Amazon.com ;

“Pre-Islamic Arabia: Societies, Politics, Cults and Identities during Late Antiquity”

by Valentina A. Grasso Amazon.com ;

“Inscriptional Evidence of Pre-Islamic Classical Arabic: Selected Readings in the Nabataean, Musnad, and Akkadian Inscriptions” by Saad D Abulhab Amazon.com ;

“The Ancient Near East: A Very Short Introduction” by Amanda H. Podany, Fajer Al-Kaisi, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East”

by Amanda H. Podany a Amazon.com ;

“The Nabataeans: Builders Of Petra” by Dan Gibson Amazon.com ;

“Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans” by Jane Taylor Amazon.com ;

”History of the Arab People” by Albert Hourani(1991) Amazon.com ;

"Arabian Sands” (Penguin Classics) by Wilfred Thesiger Amazon.com

Frankincense

Pure frankincense comes in the form of pale, yellow, translucent, gummy blobs. It has a natural oil content, which means that it burns well. A number of medicinal qualities have been ascribed to it. At spice and perfume shops in modern Omani markets pebble-like clumps frankincense are sold in baskets. Buyers often hold the clumps up to the light. They more light that penetrates it the better quality.

Frankincense produces musky, lemony smoke. It has traditionally been burned on the top of coals in censors made of ceramic or stone. Saudi ones are made of wood and decorated with mirrors. Modern electric ones from Taiwan are made of aluminum and come with a chord.

In the Arab world, frankincense is burned to scent clothes and rooms and ward off evil spirits. As a parting gesture at parties and gatherings burning frankincense is passed around so men can douse their beards in the smoke and women do the same with their hair.

Describing the burning of freshly harvested frankincense, Ashon Molavi wrote in Business Week: “Mohammed flicks a lighter and touches the frankincense with flame. There is a sizzling sound, and pale smoke dances and disappears. Mohammed fans the smoke toward me and urges me to run it through my hair.”

Myrrh and Other Goods Carried in the Frankincense Trail

myrrh

Myrrh is another Arabian aromatic traditionally used as an anointing oil and base for cosmetics and perfumes, medicines, fumigants and cooking ingredient. It was used in royal mummies in ancient Egypt and as an ingredient in sacred ointments used by Jews in the Old Testament. Before his crucifixion Jesus was offered myrrh with wine, which he refused. After his death his body was treated with "a mixture of myrrh and aloes."

Myrrh, “Commiphora” , comes from a desert tree with bright white bark. At one time it cost three times more than frankincense. Myrrh is produced in South Yemen near Mablaqah Pass.

Indigo was carried with the frankincense. Some of it was grown locally. Some was brought from India. Until fairly recently dark blue indigo loincloths were favored by tribes of "blue men" Bedouins in southern Arabia. In the chilly highlands, Bedouin claimed that a mixture of indigo and sesame oil applied to their skins helped keep them warm. The frankincense caravans also gold and precious stones.

Frankincense, Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Bible and the Three Wise Men

Babylonians, Sumerians, Assyrians and Persians offered frankincense and other aromatics to their gods. Known as the "perfume of the gods," frankincense was used in ancient Egyptian rites and as a base for perfumes and an ingredient in mummy preservation oils. The first known reference to frankincense is an inscription on the 15th-century B.C. tomb of Queen Hatshepsut. It describes expeditions sent to Punt (probably Somalia) to fetch it.

In the Bible frankincense symbolized divinity and myrrh was associated with death and persecution of Jesus. When the Queen of Sheba made her celebrated visit to Solomon she brought a "a very great retinue, with camels bearing aromatics and very much gold.” Myrrh and frankincense are mentioned in the New Testament as two of the three gifts (alongside gold ) that the magi "from the East" — The Wise Men — presented to the Christ Child (Matthew 2:11).

Ruth Eglash wrote in the Washington Post, “Frankincense and myrrhare forever intertwined with the Christmas story as the gifts the wise men took to the baby Jesus in Bethlehem. While frankincense endured, myrrh almost disappeared after the fall of the Roman Empire. The balsamon tree, whose extract was used to make myrrh’s exotic perfumes and embalming oil, no longer grew on the banks of the Dead Sea, where ancient Hebrew farmers worked. Although various species of the plant — known scientifically as ―commiphora — were found in other places in the Middle East, as well as in Asia, Africa and the Americas, the myrrh industry was all but dead in the Holy Land. [Source: Ruth Eglash, Washington Post December 24, 2016]

Frankincense and the Greeks and Romans

The Romans and Greeks craved frankincense, which was as valuable as gold. Describing Greece in 450 B.C., when Athens was its peak, Herodotus wrote, "The whole country is scented [with aromatics from Arabia] and exhales an odor marvelously sweet." Herodotus wrote the place where frankincense grew was guarded by flying serpents. Another Greek historian wrote of the people, "many suppose that they are partaking of ambrosia."

Boswellia flower One of the main purposes of frankincense was to hide awful smells. The Romans used it as a deodorant and for perfumed cremation rites. Nero reportedly used a year's supply at the funeral for his consort Poppaea. In Roman times, frankincense was widely used to consecrate temples, mask the odor of cremations, make cosmetics and treat illness such as gout and a "broken head" and "malignant ulcers about the seat."

The frankincense trade was its peak in the A.D. 2nd century, when South Arabia shipped more than 3,000 tons annually to Greece and Rome. The whole trade was controlled by a cartel not unlike OPEC of today. Pliny identified the tribes that produced frankincense and myrrh as "tent dwellers" called the Scenitae. "They are the richest races in the world."

On the location of the frankincense trail Pliny wrote: "The export of frankincense is along one narrow track" in "”octo mansionibus distant” " that lay along eight oases, each a day apart to the east and south of Shabawa.” He also wrote that Alexandria was major processing center for frankincense and that a rigid security system was set up to protect it. "Good heavens! No vigilance is sufficient to guard the factories...before [the workers] are allowed to leave the premises they have to take off all their clothes...Frankincense...is conveyed to Sabota on camels...The kings have made it a capital offense for camels so laden to turn aside from the high road."

Strabo on the Land Frankincense

Strabo (64 B.C. – c. A.D. 24) was a Greek geographer, philosopher, and historian who came from Asia Minor at around the time the Roman Republic was becoming the Roman Empire. Strabo is best known for his work Geographica ("Geography"), which describes the history and characteristics of people and places in different regions known during his lifetime, [Source: Wikipedia]

Strabo wrote in A.D. 22: “XVI.iv.25. The aromatic country, as I have before said, is divided into four parts. Of aromatics, the frankincense and myrrh are said to be the produce of trees, but cassia the growth of bushes; yet some writers say, that the greater part (of the cassia) is brought from India, and that the best frankincense is that from Persia. According to another partition of the country, the whole of Arabia Felix is divided into five kingdoms (or portions), one of which comprises the fighting men, who fight for all the rest; another contains the husbandmen, by whom the rest are supplied with food; another includes those who work at mechanical trades. One division comprises the myrrh region; another the frankincense region, although the same tracts produce cassia, cinnamon, and nard. Trades are not changed from one family to another, but each workman continues to exercise that of his father. The greater part of their wine is made from the palm. [Source: Strabo: Geography, Book XVI, Chap. iv, 1-4, 18-19, 21-26, c. A.D. 22, Strabo, The Geography of Strabo: Literally Translated, with Notes, trans. by H. C. Hamilton & W. Falconer (London: H. G. Bohn, 1854-1857), pp. 185-215]

frankinsence In Dhofar Oman “A man's brothers are held in more respect than his children. The descendants of the royal family succeed as kings, and are invested with other governments, according to primogeniture. Property is common among all the relations. The eldest is the chief. There is one wife among them all. He who enters the house before any of the rest, has intercourse with her having placed his staff at the door; for it is a necessary custom which every one is compelled to observe, to carry a staff. The woman, however, passes the night with the eldest. Hence the male children are all brothers. They have sexual intercourse also with their mothers. Adultery is punished with death, but an adulterer must belong to another family.

“A daughter of one of the kings was of extraordinary beauty, and had fifteen brothers, who were all in love with her, and were her unceasing and successive visitors; she, being at last weary of their importunity, is said to have employed the following device. She procured staves to be made similar to those of her brothers; when one left the house she placed before the door a staff similar to the first, and a little time afterwards another, and so on in succession, but making her calculation so that the person who intended to visit her might not have one similar to that at her door. On an occasion when the brothers were all of them together at the market-place, one left it, and came to the door of the house seeing the staff there, and conjecturing some one to be in his apartment, and having left all the other brothers at the marketplace, he suspected the person to be an adulterer; running therefore in haste to his father, he brought him with him to the house, but it was proved that he had falsely accused his sister.

“Merchandise is conveyed from Leuce-Come-to Petra, thence to Rhinocolura [modern Al-Arish] in Phoenicia, near Egypt, and thence to other nations. But at present the greater part is transported by the Nile to Alexandria. It is brought down from Arabia and India to Myus Hormus [modern Bãr Safajah],, it is then conveyed on camels to Coptus of the Thebaïs, situated on a canal of the Nile, and Alexandria.

branches of frankincense tree in Yemen

“Some merchandise is altogether imported into the country, others are not altogether imports, especially as some articles are native products, as gold and silver, and many of the aromatics; but brass and iron, purple garments, styrax, saffron, and costus (or white cinnamon), pieces of sculpture, paintings, pieces of statues, are not to be procured in the country. They look upon the bodies of the dead as no better than dung, according to the words of Heracleitus, "dead bodies more fit to be cast out than dung;" wherefore they bury even their kings beside dung-heaps. They worship the sun, and construct the altar on the top of a house, pouring out libations and burning frankincense upon it every day.”

Early Frankincense Trail Routes

In ancient times, the area around Qana (present-day Bir Ali on the Gulf of Aden in Yemen) was a major frankincense production area. In the early years of the trade, frankincense was mainly carried on the sea or on land routes in donkey caravans in which the distances between towns and water sources was not that great.

Between 2000 B.C. and 1000 B.C., complex trade network evolved to transport frankincense and other items overland that traversed long distances over the desert, where water was scarce. Many archeologists believe these routes were developed after the domestication of the camel, which could travel further on much less water than donkeys. Some scientists believe the trade began before the domestication of the camel, before the region changed from savannah to desert.

Caravanserai and towns grew up around the water sources. Some of these became quite rich and even became the center of kingdoms.

Frankincense Trail Routes

The Frankincense Trail caravan routes passed through a series of kingdoms — Main, Hadramawr, Sheba, and Qataban — in what is now Yemen, and then paralleled the Red Sea coast, about 70 miles inland, and passed through Mecca and Medina in present-day Saudi Arabia before reaching it destination, Petra in the kingdom of Nabataea in what is now Jordan.

From Petra, frankincense moved in overland routes to Asia Minor, Palmyra, Damascus, and the Parthian Empire, centered in present-day Iran, or to relatively close Gaza and Alexandria, where it was transported to ports in the Roman Empire. The exact route is largely unknown and archeologists are still trying to sort it out.

Frankincense also traveled north on maritime routes from Arabia Felix (Happy Arabia) to the Mediterranean, where much of it ended up in Greece and Rome. The main seaport for the frankincense-producing Dhofar region was Sumhuram in present-day Oman. It now lies inland from the sea and consists of a fortress and the remains of houses and storerooms. From Sumhuram the frankincense was transported 400 miles to Qana, in present-day Yemen, where it was loaded on larger ships bound for India and the Sinai.

According to “Periplus of the Erythaean Sea” , an ancient navigation manual compiled by an unknown Greek the frankincense was moved "to Qana on rafts held up by inflated skins after the manner of the country, and in boats."

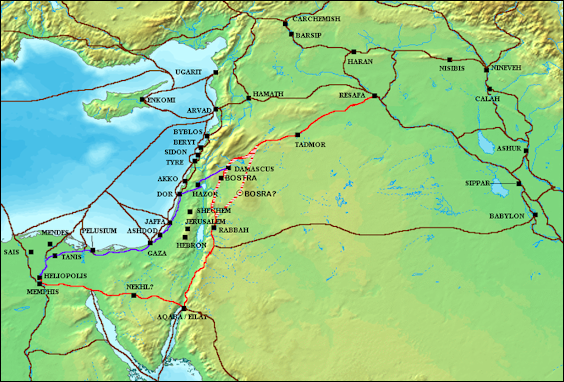

Ancient Levant trade routes

Frankincense Trail Cities

Legends of the frankincense trades became associated with the a city called Ubar (Iram). Ubar (60 miles from Salahar) is ancient fortress city mentioned in the Koran as "Iram of the columns” and described by early European explorers as "the Atlantis of the Sands.” It reached its peak as the source of much of the frankincense for the Frankincense Trail trade route and was said to be “rich in treasure, with date gardens and a fort of red silver.” The ruins of Ubar were discovered under the sand in 1992 using satellite imagery and clues gleaned from ancient historians and European explorers. Between 1992 and 1994, a fortress, administrative center and protected water supply were uncovered under the sand. Remain from neolithic times, the frankincense era, and the early Islamic era have all been found.

Uber contains remains that date back to 5,000 B.C. It thrived a thousand years and then suddenly collapsed around the A.D. 4th century. According to one theory it was built over a limestone cave which collapsed suddenly and the city was swallowed into the sand. In the Koran, Ubar was characterized as a kind of Muslim version of decadent Babylon and was destroyed by Allah because the people were wicked. A more likely explanation for Ubar’s demise is that it died with the collpase of the frankincense trade and with the Christianising of the Roman Empire.

In the late 1990s, archeologists discovered 65 separate archeological sites on the frankincense trail west of Ubar in Oman and Yemen. The finds included a pair of ancient fortresses like the one at Ubar, 30 “triliths” (stone markers), Stonehedge-like standing stones and boulders with inscriptions of Yemeni-style daggers. Many of the sites were found using satellite imagery and following the most logical route that caravaneers at that time would have used. Locals along the route actually pointed out the sites. One site contained 2000-year-old porcelain from China and stoneware from Vietnam.

Other places associated with the Frankincense Trail include Timna, the capital of the Qatabanian kingdom and a powerful city, and Hadramis, which grew rich when the frankincense trade was at its peak, controlling the routes on which it flowed to the Romans and Greeks.

Hadramawt Valley in Yemen

Hadramawt is a region in south-central Yemen with many associations to the Frankincense Trail. The most fertile lands of the region are in the east where the isolated valley of Wadi Hadramwat narrow and bends towards the sea. Here you cam find the sister cities of Shibam, Sayun and Tarim. The Hadramawt is somewhat reminescient of the Nile Valley in that parts of it are ribbons of vivid green surrounded by barren, sterile hills and canyon walls. Along the roads today you can see stunning mud and stone houses, men riding donkeys, camel carts loaded with alfalfa, groves of date palms, fortress farms, fig trees, pools of water, cliffs, rock formations, shepherds with their flocks, women wearing broad straw hats and covered from the head to toe in black abayas.

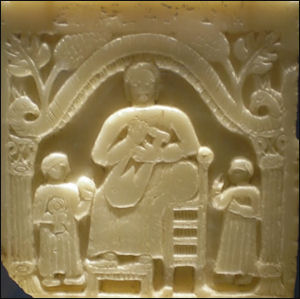

Frankincense-Trail-era art Wadi Hadramawt is the largest wadi on the Arabian peninsula. It is extends for about 100 miles and is flanked by stone deserts. The main valley is about 300 meters deep and the valley floor sits at an elevation of 700 meters. In some places the valley is 20 miles wide. As one travels deeper into it the walls get narrower and narrower. Although the region is very dry, the wadi is comprised of many tributary wadis that funnel water and fertile silt into the valley bottom, which can support 200,000 people through agriculture and herding.

Wadi Hadramawt has been inhabited by a number of civilizations. Before the A.D. 3rd century it was part of Shawba. Beginning in the 16th, it was fought over by the Kathirids and Quaitis. The Ottomans never really controlled it. No colonial power had much influence in the region until the British signed some agreements with local sheiks.

Shawba (220 miles east of Aden) was once one of the most powerful towns in Arabia. The capital of the Hadramawt Valley, it covered 500 acres and housed 5,000 people. Thriving for about 1,000 years beginning around 800 B.C., it grew rich by monopolizing and taxing the frankincense caravan routes. Fine ivories, fresco panels, stone incense burners, pillars inscribed with griffins unearthed in at Shabwah are in the National Museum in Aden. Shawba suddenly collapsed around A.D. 220. Archeologists aren’t sure. Some believe they over-cultivated their land. High the salt content in the soil around the site indicates over-irrigation may have played a role in its decline. Salt is still mined under the ruins. Now many

Marib and Sheba in Yemen

Present-day Yemen was once part of the ancient kingdom of Saba (Biblical Sheba), the most well-known and strongest of the kingdoms that appeared along the Frankincense Trail trade routes. It first appeared around 1000 B.C. and endured to the A.D. 4th century. The Koran describes Saba as a land with "two gardens on the right hand and the left...A fair land and indulgent Lord!" Because the people rejected Allah they were cursed with "gardens bearing bitter fruit, the tamarisk and here and there a lote-tree."

Marib (100 miles east of San’a) was the capital of Saba (Biblical Sheba) and the largest of the caravan cities on the Frankincense Trail. Located at an important passage from the Qana frankincense production areas through the Hadramawt Valley, it grew from rich trade and supported a large population with agriculture nourished by water from a massive earthen dam that was built in the 8th century B.C. in a wadi between two mountains and stood for more a thousand years.

Frankincense-Trail-era art Over time the dam was enlarged. When Marin was at its peak, the dam was 680 meters long and 16 meters high and embraced sluice gates made from 500-pound stone blocks. It irrigated an area of 96 square miles and supported 50,000 people and the caravans and merchants that passed through. According to one inscription from the Himyarites “20,000 men, 14,600 camels and 12,000 pairs of donkeys were needed just to repair it.

Archeologist believe that as Sheba declined the dam at Marib was neglected. The reservoir silted up and large rocks blocked the irrigation canals. When the dam broke open around A.D. 570. Sheba collapsed.

Marib today is regarded as the most impressive archeological site in Yemen. The ruins are scattered over a wide area. In Old Marib, you can see the remains of blocky, multi-story buildings. Some have small windows and slabs with Sabean inscriptions. One of the most famous inscriptions found at site was a request to the moon god for protection of the requester’s sons and favors of their king. Statues of bronze and alabaster found here have made their way to some of Yemen’s museums.

There is a ruined an oval-shaped temple dedicated to the Sabaean moon god Ilumquh. A fine example of South Arabian architecture, it contains eight thick rectangular limestone pillars that rise like standing stones from the stone-littered desert. Little remains of the Great Dam, other than the sluice, and the canal network that once made the desert bloom.

Modern Baraqish (20 miles off the San’a-Marib Road) is the home of Main, another ancient kingdom on the Frankincense Trail. The city was founded around 400 B.C. and was still occupied in the mid-1700s. The 14-meter-high wall and 57 time bastions largely intact. There are also a domed ruins of a small mosque; a small masonry temple with images of sacrificial ibex and gazelles; dancing girls, offerings of wine; and rows of bird-like men with lyres and war clubs.

Decline of the Frankincense Trail and Rise of the Maritime Silk Road

Beginning around the A.D. 1st century, trade picked up between India and Rome and the Greek kingdom in Egypt on what became the maritime Silk Road. Ships traveled on the monsoons between India and the Middle East and navigated the Red Sea to points, where short caravans could take goods to Alexandria on the Mediterranean Sea. A number of ports in the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea — including Aden and Al-Munza (north of the Bab al Mandab strait, an entrance to the Red Sea) — grew rich from the trade at the expense of the land routes.

Frankincense-Trail-era art

from Yemen One of the greatest ancient Middle East ports was Berenlike on the Red Sea. In the 1990s archaeologists discovered this ancient city under the sands about 600 miles south of modern-day Suez, near the border of Egypt and Sudan. They found evidence of trade with Thailand and Java, and inscriptions in 11 languages including Greek, Hebrew Coptic and Sanskrit. It was surmised that the ships and crews mostly came from India based on the presence of lots teak, a wood native to India and Southeast Asia.

Berenlike was founded in the 3rd century B.C., rose in importance in the 1st century B.C. and was at its peak in the A.D. 1st century. It was abandoned in the 3rd and 4th centuries and was reborn in the 5th century and thrived until it silted over in the 6th century. It was located far south of the Mediterranean because of unfavorable winds in the Red Sea.

The collapse of the frankincense trade was brought about in part by the rise of Christianity and ban of pagan practices, many of which required frankincense, and replacing cremations with burials in the forth century. It was dealt a further blow with the rise of Islam. Islam has few rituals and few uses for incense.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024