Home | Category: Literature

GILGAMESH

Gilgamesh The “ Story of Gilgamesh” is the world’s oldest known epic and regarded by many as the world’s first piece of literature. It is an epic about a legendary Sumerian king named Gilgamesh, who oppressed his people, defied the gods and, like Apollo or Hercules, attempts to find the secret to the Afterlife, only to lose his most treasured friend — returning home an older, wiser and a more compassionate monarch. Gilgamesh is believed to have been a real person. The story has been traced to the Akkadians.

First recorded around 2000 B.C., Gilgamesh stories are based on a Mesopotamian ruler of the same name who governed the city of Uruk about seven hundred years earlier. Originally written in Akkadian, these stories were translated into several Near Eastern languages and became the most famous literary creation of the ancient Babylonians. Ira Spar of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The myth known today as The Epic of Gilgamesh was considered in ancient times to be one of the great masterpieces of cuneiform literature. Copies of parts of the story have been found in Israel, Syria, and Turkey and references to the hero are attested in Greek and Roman literature. [Source: Ira Spar, Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art "Gilgamesh", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The Story of Gilgamesh” — often also referred to as “The Epic of Gilgamesh” — has been dated to around 1200 B.C. Among those who have been inspired by the story were Philip Roth and Saddam Hussein. Saddam wrote a novel inspired by the epic called “Zabibah and the King”. The Japanese anime classic “Princess Mononoke” is loosely based on one episode of the Gilgamesh story. In this episode a growing urban area requires resources from a forest but is unable to gain access until a the guardian deity Funbaba is driven out. Gilgamesh and his sidekick Enkidu fight with and kill Funbaba.

See Separate Article: GILGAMESH STORY UNTIL HE SLAYS THE BULL OF HEAVEN africame.factsanddetails.com ; GILGAMESH STORY: FROM THE NETHER WORLD TO THE END africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Gilgamesh: A New English Version” by David Mitchell (Free 2004), an excellent translation. Amazon.com;

“The Epic of Gilgamesh: A Norton Critical Edition” by Benjamin R. Foster (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Epic of Gilgamesh” (Penguin Classics) by Andrew George (2003) Amazon.com;

“Gilgamesh the King” (The Gilgamesh Trilogy) Book 1 of 3: The Gilgamesh Trilogy by Ludmila Zeman, Illustrated, for Kids, (1998) Amazon.com;

“Epic of Gilgamesh, illustrated for adults, Valentin Rey (2024) Amazon.com;

“Gilgamesh: The Life of a Poem” by Michael Schmidt (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Buried Book: The Loss and Rediscovery of the Great Epic of Gilgamesh” by David Damrosch (2007) Amazon.com;

“Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others” by 1989) Amazon.com;

“Before the Muses”, An Anthology of Akkadian Literature, by Benjamin R Foster (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Library of Ancient Wisdom: Mesopotamia and the Making of History” by Laura Selena Wisnom (2025) Amazon.com;

“From Distant Days: Myths, Tales, and Poetry of Ancient Mesopotamia” by Benjamin R Foster (1995) Amazon.com;

Website:The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature etcsl.orinst.ox

Evolution of the Gilgamesh Story

Gilgamesh dates back to around 1800 B.C. (the Old Babylonian period). The final and most popular version was produced somewhere between 1300 and 1000 B.C., and the original Sumerian poems that the later epic was based upon date to the late third millennium B.C.

Joan Acocella wrote in The New Yorker: ““There was a real king called Gilgamesh, it seems. Or, at least, his name appears in a list of kings compiled around 2000 B.C., and he probably lived in the first half of the third millennium B.C. For at least a thousand years after his death, poems were written about him, in various Mesopotamian languages. [Source: Joan Acocella, The New Yorker, October 7, 2019]

Then, sometime between 1300 and 1000 B.C., one Sin-leqi-unninni (his name means “The moon god Sin hears my prayers”) collected and edited the stories. We might call Sin-leqi-unninni a scribe or a redactor. According to one scholar, he was also a professional exorcist. What matters is that he pulled together the Gilgamesh poems that he had at hand and, adding this and deleting that, and attaching a beginning and an end, he made a unified literary work, in his language, Akkadian. This composition is what Assyriologists call the Standard Version of “Gilgamesh.” It was incised on eleven tablets, back and front, with roughly three hundred lines on each tablet.

Gilgamesh Story

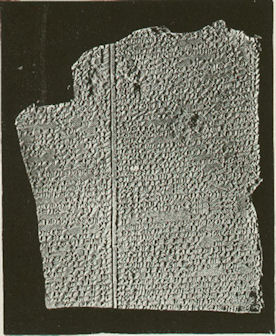

Gilgamesh Tablet According to the story Gilgamesh ruled Uruk, one the great cities of Sumer around 2800 B.C. In the first half of the epic Gilgamesh is mainly concerned with performing heroic deeds and making a name for himself. Towards the end he becomes consumed with him searching for a plant that will bring eternal life. Among his feats are killing wild bulls and chopping down cedar trees in what is now Lebanon. He ultimately fails in his effort to elude death — he finds the plant of immortality but has it snatched away by a snake — but achieved immortality by building Uruk’s great city wall.

Ira Spar of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The poem begins by explaining that Gilgamesh, although he thought that he "was wise in all matters," had to endure a journey of travail in order to find peace. Two-thirds human and one-third deity, the hero as king is unaware of his own strengths and weaknesses. He oppresses his own people. In response to complaints by the citizens of Uruk, the gods create Enkidu, a double, who becomes the hero's friend and companion. Initially described as a wild animal–like creature, Enkidu ("Lord of the Pleasant Place") has sex with a temple prostitute and is transformed into a civilized being. No longer animal-like, he now possesses wisdom "like a god," a distinguishing characteristic of humans. [Source: Ira Spar, Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art "Gilgamesh", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“After an initial confrontation, Gilgamesh and Enkidu become friends and decide to make a name for themselves by journeying to the Cedar Forest to fight against Humbaba, the giant whom the gods have placed as guardian of the sacred trees. The two kill the monster and take cedar back to Uruk as their prize. Back in Uruk, the goddess Ishtar, sexually aroused by Gilgamesh's beauty, tries to seduce him. Repulsed, the headstrong goddess sends the Bull of Heaven to destroy Uruk and punish Gilgamesh. But Gilgamesh and Enkidu meet the challenge and Gilgamesh slays the bull. The gods retaliate by causing Enkidu to fall ill and die. Gilgamesh, devastated by the death of his friend, now realizes that he is part mortal and sets out on a fruitless journey to seek immortality. \^/

“On his travels in search of the secret of everlasting life, Gilgamesh meets a scorpion man and later a divine female tavern keeper who tries to dissuade him from continuing his search. But Gilgamesh is arrogant and determined. Upon learning that Uta-napishtim ("I Found Life"), a legendary hero who had obtained eternal life, dwelt on an island across the "Waters of Death," Gilgamesh crosses the sea and is greeted by the immortal hero. Uta-napishtim explains to Gilgamesh that his quest is in vain, as humans were created to be mortal. But upon questioning, Uta-napishtim reveals that he was placed by the gods on this remote island after being informed that the world would be destroyed by a great flood. Building a boxlike ark in the shape of a cube, Uta-napishtim, the Babylonian creation myths, took on board his possessions, his riches, his family members, craftsmen, and creatures of the earth. After riding out the storm, he and his wife were granted immortality and settled on the island far from civilization. Devastated by this news and realizing that he, too, will someday expire, Gilgamesh returns to Uruk and examines its defensive wall. Finally, he comprehends that the everlasting fame he so vainly sought lay not in eternal life but in his accomplishments on behalf of both his people and his god. \^/

Patchwork, Fragments and Missing Sections of Gilgamesh Texts

Joan Acocella wrote in The New Yorker: ““We don’t have a complete copy of Sin-leqi-unninni’s tablets. Through the actions of time, wind, and, above all, war — Nineveh, with Ashurbanipal’s library, was attacked and destroyed by neighboring forces in 612 B.C. — a great deal of the text was lost. Some of the holes can be plugged with material from other Gilgamesh poems, but even once that has been done important sections are missing. Of an estimated thirty-six hundred lines, we have only thirty-two hundred, whole or in part. (Translations often supply ellipses where text is missing, and use italics and brackets to mark varying degrees of conjecture.) [Source: Joan Acocella, The New Yorker, October 7, 2019]

“Furthermore, the thing that we are looking at, after the insertions, is a patchwork of texts created at various times and places, in what are often different, if related, languages. One highly respected translation, by Andrew George, a professor of Babylonian at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, gives what remains of Sin-leqi-unninni’s text and then appends the “Pennsylvania tablet”; the “Yale tablet”; the “Nippur school tablet,” in Baghdad; the “fragments from Hattusa” (now Boğazköy, in central Turkey); and so on.

Scholars cannot afford to ignore these outliers, because the symbols that constitute cuneiform, up to a thousand of them, changed over the millennium that produced Sin-leqi-unninni’s materials. So the word for “goddess of love and war” on a fragment in Baghdad may be different from its analogue in the vitrines of the British Museum. Indeed, meanings may change in the present as well, as additional discoveries are made. After a new piece came to light in 2015, George wrote that the energetic Enkidu and Shamhat had not one but two weeklong sex acts before repairing to Uruk. The text has no stability. It shifts in your hands.

History of Gilgamesh Story

In the period before 2700 B.C., the Sumerians considered most of their kings to be gods, or at least heroes. The deification and heroization of kings mostly ceased after Gilgamesh, king of Uruk. No contemporary information is known about Gilgamesh, who, if he was in fact an historical person, would have lived around 2700 B.C. Some early Sumerian tales about Gilgamesh make the point that he was not a great king. The story, "Gilgamesh and Agga of Kish," shows him forced to acknowledge the overlordship of the Great King of Kish, possibly Mesannepada of Ur. [Source: Internet Archive, from UNT]

Ira Spar of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The tale revolves around a legendary hero named Gilgamesh (Bilgames in Sumerian), who was said to be the king of the Sumerian city of Uruk. His father is identified as Lugalbanda, king of Uruk, and his mother is the wise cow goddess Ninsun. No contemporary information is known about Gilgamesh, who, if he was in fact an historical person, would have lived around 2700 B.C. Nor is there any preserved early third-millennium version of the poem. During the twenty-first century B.C., Shulgi, ruler of the Sumerian city of Ur, was a patron of the literary arts. He sponsored a revival of older literature and established academies of scholars at his capital Ur and at the holy city of Nippur. Shulgi claimed Lugalbanda as his father and Gilgamesh as his brother. [Source: Ira Spar, Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art "Gilgamesh", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

Sumerian King List lists Gilgamesh

“Although little of the courtly literature of the Shulgi academies survives, and Sumerian ceased to be a spoken language soon after the end of his dynasty, Sumerian literature continued to be studied in the scribal schools of the following Old Babylonian period. Five Sumerian stories about Gilgamesh were copied in these schools. These tales, which were not part of an epic cycle, were originally oral narratives sung at the royal court of the Third Dynasty of Ur. \^/

“"Gilgamesh and Akka" describes the triumph of the hero over his overlord Akka, ruler of the city of Kish. "Gilgamesh and Huwawa" recounts the journey of the hero and his servant Enkidu to the cedar mountains, where they encounter and slay the giant Huwawa, the guardian of the forest. A third tale, "Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven," deals with Gilgamesh's rejection of the amorous advances made by Ishtar, the Queen of Heaven. Seeking revenge, the goddess sends the Bull of Heaven to kill Gilgamesh, but the hero, with the assistance of Enkidu, slays the monster. In "Gilgamesh and the Netherworld," the hero loses two sport-related objects, which fall into the Netherworld. Enkidu descends into the depths to find them and, upon his return to life, describes the horrid fate that awaits the dead. In the final composition, "The Death of Gilgamesh," the hero dreams that the gods are meeting to review his exploits and accomplishments. They decide that he, like all of humankind, shall not be granted eternal life. \^/

“In addition to the Sumerian compositions, young scribes studying in the Old Babylonian schools made copies of different oral stories about the hero Gilgamesh. One noteworthy tale was sung in Akkadian rather than in Sumerian. Called "Surpassing All Other Kings," this poem combined some elements of the Sumerian narrative into a new Akkadian tale. Only fragments of this composition survive. By the end of the eighteenth century B.C., large areas of southern Mesopotamia, including Nippur, were abandoned; the scribal academies closed as the economy collapsed. A shift in political power and culture took place under the newly ascendant Babylonian dynasties centered north of Sumer. Hundreds of years later, toward the end of the second millennium B.C., literary works in Babylonian dominated scribal learning. Differing versions of classic compositions, including the Akkadian Gilgamesh story, proliferated and translations and adaptations were made by poets in various lands to reflect local concerns. \^/

“Some time in the twelfth century B.C., Sin-leqi-unninni, a Babylonian scholar, recorded what was to become a classic version of the Gilgamesh tale. Not content to merely copy an old version of the tale, this scholar most likely assembled various versions of the story from both oral and written sources and updated them in light of the literary concerns of his day, which included questions about human mortality and the nature of wisdom. "Surpassing All Other Kings" now became a new composition called "He Who Saw the Deep." In the poem, Sin-leqi-unninni recast Enkidu as Gilgamesh's companion and brought to the fore concerns about unbridled heroism, the responsibilities of good governance, and the purpose of life. The new version of the epic explains that Gilgamesh, although he is king of Uruk, acts as an arrogant, impulsive, and irresponsible ruler. Only after a frustrating and vain attempt to find eternal life does he emerge from immaturity to realize that one's achievements, rather than immortality, serve as an enduring legacy.” \^/

Archaeologist George Smith announced the discovery of “The Epic of Gilgamesh” in 1872. He found and translated the tablets which contained the epic and told the story of the cleansing flood. Historian Marina Warner observes that “his joy was occasioned above all by the independent corroboration the poem offered to the historicity of the Bible. He was a fervent Christian and longed, as many did, for archaeology to prove the scriptures’ reliability.” When Smith first shared the story with the public it “was the first time the ‘Epic of Gilgamesh’ had been heard and understood after an interval of two thousand years: the longest sleeper ever among the world’s great poems.” What this means, she continues, is that we read it as representing a kind of “double history, as an ancient epic and a modern narrative poem.” [Source: David L. Ulin, Los Angeles Times, February 27, 2014]

George Smith and the Discovery of the Story of Gilgamesh

After the fall of the Assyrian Empire in the 6th century B.C., the first great library of the world — which contained the Gilgamesh story — was also lost. In 1844,Sir Austen Henry Layard, a British lawyer and pioneering archaeologist, began the first excavations of the Assyrian and Babylonian ruins in Nineveh and Nimrud and the great library — the library of Ashurbanipal — was found. Many of the actual discoveries were made by Hormuzd Rassam, an Iraqi archaeologist, who was friend and protege of Layard and who excavated Nineveh and Nimrud through the 19th century, making many great discoveries only to have the credit taken by Englishmen, whose acceptance and admiration he greatly craved. [Source: The New Yorker]

Thousands of tablets from the library were taken to the British Museum, where they were examined by an amateur linguist named George Smith, who had ended his formal education at 14 and taught himself to read Akkadian. One day in 1867 during his lunch break from his day job as a printer’s engraver he was combing through the tablets — which were mostly records of business and government transactions — he came across what seemed to be a narrative of the Biblical flood and with that began the rediscovery of “The Story of Gilgamesh”.

Many of the tablets that contain the flood story were painstakingly assembled from fragments. After Smith made his initial discovery from a small fragment he had to wait a few days for restorer Robert Ready to show to reconstruct the tablet and make it easier to read. On the wait and the Eureka moment his friend E.A. Wallis Budge later recalled, “Smith was constitutionally a highly, nervous man, and his irritation at Ready’s absence knew no bounds.” When Ready finally did show up and Smith could read the text, Budge said, “Smith took the tablet and began to read over the lines that Ready had brought to light and when he saw that they contained the portion of the legend he had hoped to find there, he said: “I am the first man to read after more than two thousand years of oblivion.” Setting the tablet on the table, Smith jumped and rushed around the room in a greats state of excitement.” He is said to have been so excited he tore off his clothes.

Smith had studied the shards of cuneiform tablets for around ten years before his discovery. Joan Acocella wrote in The New Yorker: In George Smith’s time, the British Museum lacked not only electrical light, but gaslight as well. (The management was afraid of fire.) Some of the higher-up staff had lanterns, but George Smith was not a higher-up. If it was a foggy day and the windows did not admit enough light to read by, he had to go home. On other days, though, he was at his post. “With devotion and patient application,” Michael Schmidt writes, these scholars “deciphered the languages, finding human voices in the clay, and a king terrified of dying came back to the long half-life of poetry.”

The Gilgamesh flood story could support the truth of Genesis, or so it seemed to Smith. “And to others. In 1872, when Smith presented his findings to the Society of Biblical Archaeology, even William Gladstone, the Prime Minister, was in attendance. The discovery became front-page news across Europe and the United States. Soon, London’s Daily Telegraph gave Smith a grant to go to the region to see if he could add to his findings. Within days, he hit pay dirt — a shard that appeared to complete the flood story — and the British Museum financed two further trips for him. On the second of these, he died of dysentery in Aleppo, at the age of thirty-six. He never lived to understand that, in fact, he had not proved the truth of the Old Testament with his clay tablet. (Both flood narratives could have been descended from older sources, quite possibly fictional.) He had done something else, though. He had discovered what was then, and still is, the oldest long poem in the world, “Gilgamesh.”

Smith wrote the first true history of the Assyrians, painstakingly translated important Babylonian texts and became the world’s foremost expert on the Akkadian language and its exceedingly difficult script. He also discovered passages from an older flood story than the one in “Gilgamesh”, dating back to 1800 B.C. , during his own archaeology work, excavating in Nineveh. He worked furiously and wrote eight important books on the Assyrians before he died in Aleppo in 1877, a decade after making his initial discovery.

Different Gilgamesh Texts

There are different Gilgamesh texts” Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: 1)The epic tale "Gilgamesh and Agga” (Akka; cos i, 550–52) tells how Gilgamesh, vassal ruler of Uruk under Agga of Kish, persuades him to resist performing its corvée duties with weapon in hand. Agga and his longboats soon appear before Uruk's walls. Only Gilgamesh himself is valiant enough to make a successful sortie. He cuts his way to Agga's boat and takes Agga captive. Having thus proved himself, however, he grandly sets Agga free and even reaffirms his overlordship, all in gratitude for the fact that on an earlier occasion Agga had taken Gilgamesh in when the latter sought his protection as a fugitive. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

2) Also in some degree warlike in spirit, but with distinct romantic overtones of the strange and the far away, is the tale of "Gilgamesh and Humbaba," which tells how Gilgamesh, to win fame, undertakes an expedition against the terrible Humbaba in the cedar mountains in the west. The adventure nearly ends in disaster, but by deceit Gilgamesh gets Humbaba in his power and, when he is nobly inclined to spare him, Humbaba rouses the anger of Enkidu, Gilgamesh's servant, who promptly kills him.

3) A mythical element enters into the tale of "Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven." The city goddess of Uruk, Ishtar, has offered Gilgamesh marriage and has been rudely refused. To avenge herself, she asks the loan of the fierce "bull of heaven" from her father Anu. Anu reluctantly grants her wish. Contrary to expectations, however, the bull does not manage to kill Gilgamesh, but is itself slain by him and Enkidu.

4) Gilgamesh exhibits a quite different friendly, attitude toward Ishtar in another story, "Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld". In this tale, Ishtar finds a tree drifting on the river, pulls it in, and plants it, in the hope of making a bed and a chair from its wood when it is fully grown. By that time, however, the tree has been taken over by the Anzu bird, the demoness Lilith, and a great serpent. In her disappointment she turns to Gilgamesh, who scares off the unwelcome guests, fells the tree, and gives her wood for her bed and chair. From the tree stub and the branches he makes what seems to be a puck and stick for some hockey-like game, and celebrates the victory with a feast. At the feast, however, a waif, who has no one to take care of her, utters a cry of protest to the god of justice and fairness, Utu, and Gilgamesh's puck and stick fall into the Netherworld. Enkidu offers to go down and bring them up and Gilgamesh instructs him in how to behave so as not to be held back down there. Enkidu, however, disregards the instructions and so must remain in the Netherworld. All Gilgamesh can do is to obtain permission for Enkidu's ghost to come up to see him. Enkidu's ghost then ascends through a hole in the earth, the two embrace, and in answer to Gilgamesh's questions Enkidu tells him in detail how people are treated in the hereafter.

5) There is also a badly damaged tale called "The Death of Gilgamesh.

Gilgamesh Themes and Art

There are a lot of versions and variations of the Gilgamesh story with different characterizations and plot twists. Gilgamesh is described as being both two-thirds god and one-third man, and two-thirds man and one-third god but ultimately is destined to same fate as ordinary men. He is strong as a “wild bull,” and impulsive and reckless. As the King of Ur he is unaware of his own strengths and weaknesses and oppresses his own people so severely the ask the gods to create a friend for him to bring him under control. .

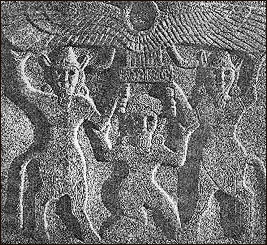

Akkadian cylinder seal

According to CCNY (City College of New York): Though the Epic of Gilgamesh “may originally have been an historical account the tale has many layers of myth and symbolism. One of those layers deals with life after death. The afterlife for the Mesopotamians mirrors the hardships the people faced in their daily existence.

According to the University of Northern Texas: “The Epic of Gilgamesh is a story of man coming to grips with his own mortality. It reaches the secular conclusion that salvation (becoming one with God) is beyond hope and that the "immortality" of man lay in his deeds and the remembrance of them — an idea that is radically different from the prevailing ideas in ancient Egypt. The Gilgamesh of the epic was a predominantly heroic, yet tragic, figure. He was not a god. [Source: Internet Archive, from UNT]

Ira Spar of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Attempts to identify Gilgamesh in art are fraught with difficulty. Cylinder seals from the Old Akkadian period (ca. 2334–2154 B.C.) onward showing nude heroes with beards and curls grappling with lions and bovines cannot be identified with Gilgamesh. They are more likely to be associated with the god Lahmu ("The Hairy One"). A terracotta plaque in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, depicts a bearded hero grasping an ogre's wrist while raising his right hand to attack him with a club. To his left, a beardless figure pins down the monster's arm, pulls his hair, and is about to pierce his neck with a knife. This scene is often associated with the death of Humbaba. The Babylonian Gilgamesh epic clearly describes Enkidu as being almost identical to Gilgamesh, but no mention is made of the monster's long hair, and although Gilgamesh is said to strike the monster with a dagger, he holds an axe rather than a club in his hand. The scene on the Berlin plaque may reflect the older Sumerian story wherein Enkidu is described as a companion rather than a double of the hero. In this older tale, Enkidu is the one who "severed [Huwawa's] head at the neck." Similar images appear on cylinder seals of the second and first millennium B.C.” [Source: Ira Spar, Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art "Gilgamesh", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

Babylonian Gilgamesh

Ishtar

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:“The great national epos of Gilgamesh, which probably had in Babylonian literature some such place as the Odyssey or the Aeneid amongst the Greeks and Romans. It consists of twelve chapters or cantos. It opens with the words Sha nagbo imuru (He who saw everything). The number of extant tablets is considerable, but unfortunately they are all very fragmentary and with exception of the eleventh chapter the text is very imperfect and shows as yet huge lacunae. Gilgamesh was King of Erech the Walled. [Source: J.P. Arendzen, transcribed by Rev. Richard Giroux, Catholic Encyclopedia |=|]

“When the story begins, the city and the temples are in a ruinous state. Some great calamity has fallen upon them. Erech has been besieged for three years, till Bel and Ishtar interest themselves in its behalf. Gilgamesh has yearned for a companion, and the goddess Arurn makes Ea-bani, the warrior; "covered with hair was all his body and he had tresses like a woman, his hair grew thick as corn; though a man, he lives amongst the beasts of the field". They entice him into the city of Erech by the charms of a woman called Samuhat; he lives there and becomes a fast friend of Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh and Ea-bani set out in quest of adventure, travel through forests, and arrive at the palace of a great queen. Gilgamesh cuts off the head of Humbabe, the Elamite king. Ishtar the goddess falls in love with him and asks him in marriage. But Gilgamesh scornfully reminds her of her treatment of former lovers. Ishtar in anger returns to heaven and revenges herself by sending a divine bull against Gilgamesh and Ea-bani. This animal is overcome and slain to the great joy of the city of Erech. Warning dreams are sent to Gilgamesh and his friend Ea-bani dies, and Gilgamesh sets out on a far journey, to bring his friend back from the underworld. |=|

“After endless adventures our hero reaches in a ship the waters of death and converses with Pir-napistum, the Babylonian Noe, who tells him the story of the flood, which fills up the eleventh chapter of some 330 lines, referred to above. Pir-napistum gives to Gilgamesh the plant of rejuvenescence but he loses it again on his way back to Erech. In the last chapter Gilgamesh succeeds in calling up the spirit of Ea-bani, who gives a vivid portrayal of life after death "where the worm devoureth those who had sinned in their heart, but where the blessed lying upon a couch, drink pure water". Though weird in the extreme and to our eyes a mixture of the grotesque with the sublime, this epos contains descriptive passages of unmistakable power. A few lines as example: "At the break of dawn in the morning there arose from the foundation of heaven a dark cloud. The Storm god thundered within it and Nebo and Marduk went before it. Then went the heralds over mountain and plain. Uragala dragged the anchors loose, the Annunak raised their torches, with their flashing they lighted the earth. The roar of the Storm god reached to the heavens and everything bright turned into darkness." |=|

Gilgamesh in the Underworld: One of the Most Famous Parts

In Gilgamesh there are descriptions of the Underworld Gilgamesh does not visit the Underworld - Enkidu is the only person who describes the Underworld and this is the result of a dream.

Kapara relief

Gilgamesh winged sun In an Old Babylonian version of the epic (probably written around 1700 - 1800 BC, but not present in the "standard version" of the story a female tavern keeper tells ilgamesh in the middle of his journey to be virtuous and concern himself with matters of the world not the afterlife:

” The life that you seek you never will find...

Gaze on the child who hold your hand.

Let your wife enjoy your repeated embrace!

For such is the destiny of mortal men.”

In “The Story of Gilgamesh” , the Underworld is described as a place where 1) a man with one son “lies prostrate at the foot of a wall and weeps bitterly over it,” 2) a man with two sons “dwells in a brick-structure and eats bread,” 3) a man with thee sons “drinks water out of waterskins of the deep,” 4) a man whose body has not been buried possesses “a spirit that does not rest,” and 5) a spirit with no one to take care of it “eats pieces of bread that have been thrown to it.”

Another Mesopotamian epic about a search for eternal life centers on Adapa, who receives special wisdom from Ea, the water god. The other gods are jealous and summon him to the land of gods. Ea tells him to be on his guard and not drink or eat anything on his visit. Adapa heeds the advise. Anu, the god of the sky, offers him some bread of life and drink of life that would bring him eternal life. The gods figured Adapa already knew so much he might as well be a god. Adapa refused and returned to earth to die. Some say this story gave birth to the Adam and Eve story.

Good Book About Gilgamesh

Joan Acocella wrote in The New Yorker: “The poet and scholar Michael Schmidt has just published a wonderful book, “Gilgamesh: The Life of a Poem” (Princeton), which is a kind of journey through the work, an account of its origins and discovery, of the fragmentary state of the text, and of the many scholars and translators who have grappled with its meaning. Schmidt encourages us to see “Gilgamesh” not as a finished, polished composition — a literary epic, like the Aeneid, which is what many people would like it to be — but, rather, something more like life, untidy, ambiguous. Only by reading it that way, he thinks, will we get close to its hard, nubbly heart. [Source: Joan Acocella, The New Yorker, October 7, 2019]

“Schmidt, in his book, sort of moseys through the poem, addressing topics as they arise. When the subject of war comes up, he nods at the wars in Iraq, which, beginning in 1990, were being waged when a number of translators of “Gilgamesh” were at work. When the characters are having sex, he discusses Assyrian sex. Did Gilgamesh and Enkidu have a homosexual relationship? He doesn’t think so, but he gives the evidence for and against. He also makes the important point that their friendship is the most tender relationship in the poem. Each night, when the two men are travelling to the Forest of Cedar, Enkidu makes a little house for Gilgamesh to sleep in, and, “like a net, lay himself in the doorway.”

“Schmidt doesn’t linger over the questions. He is broadminded. He is a poet, and the thing he is interested in is obtaining poetry, getting the grapes of carnelian truly red and round, getting Uta-napishti’s deathless world appropriately wan and bloodless. Going through the poem tablet by tablet, he stops at his favorite parts and reads to us from various translations. How excited he gets when the men leave for the Forest of Cedar! How ravished he is by the forest’s richness!

“A pigeon was cooing, a turtledove answering,

The forest was joyous with the [cry] of the stork,

The forest was lavishly joyous with the francolin’s [lilt].

Mother monkeys kept up their calls, baby monkeys chirruped.

“Sometimes Schmidt seems less a literary historian than just a friend, who has come over to our house for the evening, with a bottle, to read us a terrific poem....Schmidt estimates that the Iliad and the Odyssey have been studied by scholars for about a hundred and fifty generations; the Aeneid, for about a hundred; “Gilgamesh,” for only seven or eight. Translators of Homer and Virgil could look back on the work of great predecessors such as Pope and Dryden. Not so with “Gilgamesh.” The first sort-of-complete Western translation was produced at the end of the nineteenth century. I was not taught the poem in school, nor was anyone I know. There is no real tradition for reading it. Modern translators are pretty much on their own.

“Schmidt has emotions about these ancient tablets. When you handle one, he tells us, “especially the apprentice copyists’ tablets that fit in the palm, almost as if we were shaking hands with the original scribe, the sensation of living contact can be intense. The fine-grained river mud was rolled and patted into shape, sliced, lifted to the eye and, in dazzling sunlight of a scribal courtyard, under supervision, the cuneiform figures were incised.”

Translators and Poets Drawn to Gilgamesh

Joan Acocella wrote in The New Yorker: “ You might think that a poem that exists in a pile of broken pieces, in an extremely dead language, would be something that translators would run from in a hurry. The very opposite is the case. Presumably because it is, as Schmidt writes, such an “uncertain, porous” thing, translators are drawn to it. Often they are not, by profession, translators or Assyriologists but just poets. Others are Assyriologists, and, unsurprisingly, not all of them look kindly on people who publish versions of “Gilgamesh” without knowing the language in which it was written. Benjamin Foster, a professor of Assyriology and Babylonian literature at Yale, told an interviewer, “I have no patience with clueless folk who think that they can translate the epic without going to the trouble of mastering Babylonian, though of course they are welcome to retell it.” [Source: Joan Acocella, The New Yorker, October 7, 2019]

“Since the mid-twentieth century, there have been, by my count, nearly a score of full-scale translations of “Gilgamesh” into English. The majority of the translators, not to speak of the commentators, have stepped forth from among Foster’s “clueless folk.” What most of these people do is read a literal translation by an expert Assyriologist and then “poeticize” it, pushing it up into verse. Such a procedure should not scandalize anyone in our time. It is, basically, how Ezra Pound wrote his so-called translations of the Chinese poet Li Po, and Auden his versions of the Icelandic Eddas. But with a text so unknown as “Gilgamesh,” so hard for any of us to read, this method certainly raises some questions.

Huluppu Tree

Translations of Gilgamesh

Joan Acocella wrote in The New Yorker: “Schmidt recommends specific translations. He is acutely aware of the age of the poem, and its fragmentary condition, and its authorlessness — “a poem without a poet,” he calls it. The translations he is most wary of are those that try to cover over that strangeness, de-“otherize” the poem, solve its riddles, and thus “free us to be contented literary consumers.” He names names: in England, Nancy K. Sandars (1960); in the United States, Stephen Mitchell (2004). Both, he says, are “guilty as charged,” guilty of producing a poem that tries to convince us that Gilgamesh is our friend down the street, with problems like our own, and speaking the words that we would say. (Or not: in Mitchell’s translation, Gilgamesh, rebuking Ishtar, claims that she implored her father’s gardener, “Sweet Ishullanu, let me suck your rod.” He’s the one she eventually turned into a frog.) [Source: Joan Acocella, The New Yorker, October 7, 2019]

“All the same, Schmidt then goes on to suggest that if we haven’t yet read “Gilgamesh” we might as well start with Sandars, to get comfortable with the poem. Next, we should move on to one of the Assyriologists, Foster or George, and find out what the surviving inscriptions actually say. Finally, Schmidt sort of goes wild and sends us to “Dictator: A New Version of the Epic of Gilgamesh” (2018), in which the Belfast-born poet Philip Terry translates the poem into “Globish,” a fifteen-hundred-word vocabulary put together by a former I.B.M. executive, Jean-Paul Nerrière, and published in 2004 as a proposed language for international business, just as Akkadian, the language of “Gilgamesh,” was the lingua franca of Near Eastern commerce in its time. Here, in Globish — with plus signs indicating missing words that Terry apparently doesn’t want to guess at and vertical lines demarcating metrical units — are the trapper’s instructions to Shamhat for seducing Enkidu:

“Here be | the man | party | girl get | ready | for a | kiss + + +

Open | you leg | show WILD | MAN you | love box

Hold no | thing back | make he | breathe hard . . .

Then he | will come | close to | take a | look + + +

Take off | you skirt | so he | can . . . | screw you.”

“I think Schmidt is having a little fun with us here, and that he has read too many “Gilgamesh” translations. My own recommendation would be the same as his for the first two stops — Sandars, to get comfortable, and, after that, one of the Assyriologists, to get uncomfortable. Then I might go to “Gilgamesh Retold” (2018), by the Anglo-Welsh poet Jenny Lewis, who teaches at Oxford. Lewis’s version is very musical, with rhymes and chimes and shifting meters. It can be blunt. Its account of the murder of Humbaba is the nastiest I know. Yet her translation is also the most tender, the most tragic — the one, I think, that might be recommended by feminist scholars. When Enkidu meets Shamhat at the water hole, there is no talk of love boxes. Enkidu strokes her thighs; he sings to her. Likewise, when, as a result of his commerce with human beings, Enkidu loses his kinship with the animals, that melancholy fact is given its due:

“Far away, under the forest’s boughs

A small gazelle still searched for him in vain

And others sniffed the air to catch his scent

But there was nothing carried on the wind

And in his mind no thought of them was left.

“But I have a bizarre proposal: it would not be a bad idea, in approaching “Gilgamesh,” to start with Michael Schmidt’s book. Yes, it is a commentary, not an end-to-end translation, but it includes a lot of translated passages — the best ones, needless to say. And Schmidt’s argument for the poem as poetry, in the modern sense — concrete, unglazed, tough on the mind — is touching and persuasive. I read the book spellbound, in one sitting. (Like “Gilgamesh,” it is short, less than two hundred pages.)

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024