Home | Category: Jewish Sects and Religious Groups / Jewish Sects and Religious Groups

HASIDIC JEWS

1917.jpg)

Jews in Khorostkiv in western Ukraine in 1917 Hasidism is a revivalist mystical movement that originated in Poland in the 18th century, They are extremely pious and emotional Jews known for their unusual clothing styles and preservation of 18th century customs and rituals. They are also known for their strong devotion to individual leaders, their ascetic lifestyles, ecstatic religion experiences, devotion to prayer and study and their emphasis on the traditional Jewish concept of simple delight in the service of God.

Hasidism (also spelled Hassidism or Chasidism) followed the example of the Baal Shem Tov (1698-1760) who said that you didn’t have to be an ascetic to be holy and promoted the idea that worship was something that one should enjoy. According to the BBC: The movement included large amounts of Kabbalic mysticism as well, and the way it made holiness in every day life both intelligible and enjoyable, helped it achieve great popularity among ordinary Jews. However it also led to divisions within Judaism, as many in the religious establishment were strongly against it. In Lithuania in 1772 Hassidism was excommunicated, and Hassidic Jews were banned from marrying or doing business with other Jews. [Source: BBC]

Hasidic Jews often speak Yiddish as their first language or their only language. They often live in isolated communities and rigidly follow strict rules but also lose themselves in mystical, ecstatic experiences with God that are not unlike those experienced by evangelical Christians.

The Hasidim still owe their allegiance to various dynasties of rabbis. Hasidic groups often are like cults led by a particular, charismatic rabbi. Among the more well known ones are Ba’al Shem Tov, Dov Baer and Jacob Joseph. The best-known Hasidic rabbis with large followings today are the Lubavitcher and the Satmarer in New York, and the Gerer, Viznitzer, and Belzer in Israel. Neo-Hasidism of Martin Buber is not a movement but rather empathy for some of the Hasidic values that relate to the spiritual predicament of mankind.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Holy Days: The World Of The Hasidic Family” by Lis Harris Amazon.com ;

“Rebbe: The Life and Teachings of Menachem M. Schneerson, the Most Influential Rabbi in Modern History” by Joseph Telushkin, Rich Topol, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Gerus Guide - The Step By Step Guide to Conversion to Orthodox Judaism” by Rabbi Aryeh Moshen Amazon.com ;

“How to Run a Traditional Jewish Household” by Blu Greenberg Amazon.com ;

“Conservative Judaism” by Behrman House Amazon.com ;

“Modern Conservative Judaism: Evolving Thought and Practice" by Rabbi Elliot N. Dorff, Rabbi Julie Schonfeld Amazon.com ;

“Reform Judaism: A Jewish Way of Life” by Charles A. Kroloff Amazon.com ;

“A Life of Meaning: Embracing Reform Judaism's Sacred Path” by Rabbi Dana Evan Kaplan Amazon.com ;

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com ;

“Judaism: History, Belief and Practice” by Dan Cohn-Sherbok Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Orthodox, Ultra-Orthodox and Hasidic Jews

Professor Joshua Shanes wrote: Of all the Jewish denominations, the Orthodox groups are perhaps most misunderstood. They all share a commitment to Jewish law — especially regarding gender roles and sexuality, food consumption and Sabbath restrictions — but there are many divisions, generally categorized on a spectrum from “modern” to “ultra” Orthodox.[Source: Joshua Shanes, Associate Professor of Jewish Studies, College of Charleston, The Conversation, June 15, 2023]

Modern Orthodoxy celebrates secular education and integration into the modern world, yet insists on a relatively strict approach to ritual observance and traditional tenets of belief. They also tend to see Zionism — the modern movement calling for Jewish national rights, today connected to support for Israel — as part of their religious worldview, rather than just a political belief.

Payot on young Hasidic man The ultra-Orthodox, on the other hand — sometimes called “Haredim” or Haredi Jews — advocate segregation from the outside world. Many continue to speak Yiddish, the traditional language of Jews in Eastern Europe, or to dress as traditional Jews did in Europe before the Holocaust.

This is especially true of Hasidic Jews, who make up about half of the ultra-Orthodox population worldwide. Hasidism is a mystical movement born in 18th-century Ukraine, but today mostly concentrated in New York and Israel. Hasidic Jews are known for being particularly strict about shunning secular culture and education, but they remain also a mystical movement focused on God’s close presence. They are divided into subgroups named after cities in Eastern Europe, and they follow leaders known as “Rebbes,” who wield enormous power in their communities.

Haredim are particularly committed to gender segregation, separating men and women beyond what previous Jewish traditions called for, and tend toward the strictest interpretation of Jewish law, even when traditional understanding of a rule has been more lenient.

Whether modern or Haredi, Orthodox Judaism sees itself as “traditional.” However, it is more accurate to say it is “traditionalist.” By this I mean that Orthodoxy is attempting to recreate a pre-modern religion in a modern era. Not only has Orthodox Judaism innovated many rituals and teachings, but people today have greater awareness that other types of life are available — creating a firm break with the traditional world Orthodoxy claims to perpetuate.

History of Hasidism

The Hasidic movement was founded in central Europe in the 18th century by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tob (Boav Shem Toyva, (1700-1760)), a mystic who lived in Medshibish Ukraine, now regarded as a great center of Hasidism. The Hasidic communities in central Europe were largely wiped out during the Holocaust. Most Hasidic Jews are found in Israel and the United States.

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: Hasidism reinterpreted teachings of Kabbalist (a form of mystical Judaism that originated in the 13th century) so that they neutralized the sting of messianic disappointment that lingered after the death of Shabbetai Tzevi (1626–76), mystic that lived in the Ottoman Empire that many believed was the Messiah (See Below). Israel ben Eliezer and his disciples redirected the longing for redemption to the experience of God in the here and now through the everyday acts of prayer, ritual, and good deeds. Rejoicing in the all-pervasive presence of God through song and dance was also deemed to be a valid form of divine service. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

In addition to writing numerous works on Kabbalah, Hasidic teachers developed a unique genre of mystical parables and stories that were eventually collected in widely circulated collections. Many of these parables and stories are ascribed to Baal Shem Tov, who himself did not write any books. Rabbi Nahman of Bratzlav (1772–1811), his great-grandson, was a particularly gifted storyteller whose mystical tales and subtle theology, rich with psychological insight, continue to exercise a unique fascination on Jews beyond the Hasidic movement.

Sabbatai Zevi and Hasidic Messiahism

Sabbatai Zevi (1626–1676) was an Ottoman Jewish mystic, false messiah and ordained rabbi from Smyrna (now İzmir, Turkey). Likely of Ashkenazi origin, he claimed to be the long-awaited Jewish Messiah and founded the Sabbatean movement. He was arrested in Istanbul and served time in several different prisons and tried for of fomenting sedition.

Jacob Kat wrote in the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences: Jewish tradition had foreseen a radical change in the status of religious law in the Messianic era. According to the widely held view, with the appearance of the Messiah the religious commandments would no longer be held binding. Throughout the Middle Ages, Messianic expectations evoked Messianic pretenders, but as they were quickly disproved, the possible implications for religious practice were not realized. [Source: Jacob Kat, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Encyclopedia.com]

Different, however, was Sabbatai Zevi, who from 1665 to 1666 succeeded in keeping all Jewry in suspenseful waiting for the final call. He introduced new religious rites and partook in forbidden food in order to demonstrate by deed the end of the old era and the commencement of the new. When called to account by the Turkish authorities for causing mass upheavals, Sabbatai Zevi, to save his life, converted to Islam. A number of his followers accepted this as a necessary stage in the process of redemption, and in the course of theological justification for the converted Messiah, heretical theologies arose which were linked with the prevailing dualistic doctrines of the cabala.

These gave rise to a number of sects, some of which were syncretisms of Judaism and Islam and lived on the margin of Jewish society, while others, although remaining within the confines of the Jewish community, were of a heretical and even antinomian or nihilistic character. These groups led a more or less clandestine existence among Jews in Turkey, Poland, Bohemia, and Moravia, thus disrupting the age-old religious unity of the Jewish people.

Hasidics developed theological responses to the Holocaust, most significantly Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902–94), head of the Lubavitcher, or Habad, branch of Hasidism. He viewed the Holocaust as the "birth pangs of the Messiah," the tribulations preceding Redemption, whose imminent advent was indicated by the "miraculous" birth of the State of Israel. The rabbi's messianic enthusiasm was expressed by his dedication to the spiritual "ingathering" of the exiled of Israel, which he pursued by establishing a worldwide program to instill in secularized and assimilated Jews a love of the Torah. Many of Rabbi Schneerson's followers believe that he himself was the longed-for Messiah, who, despite his death, will soon return as the manifest Redeemer of Israel and the world. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

See Separate Article: SATMARS AND LUBAVITCHERS — THE LARGEST HASIDIC SECTS africame.factsanddetails.com

Hasidim Beliefs

Hasidism emphasized of more mystical, or spiritual approach to Judaism that relied more on personal experience than on formal education, eschewing the traditional view that study and education was the best way to know God. The movement was considered quite radical at the time, and those who opposed it were called mitnagdim, meaning "opponents." [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

Jacob Kat wrote in the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences: Hasidism arose in Poland in the middle of the eighteenth century. Originating in the small rural communities of Podolia, this movement centered on popular religious leaders of lower rank, wandering preachers, popular healers, and the like. Its first leader, Israel Ba’al Shem-Tov (who died in 1760) possessed an extraordinary gift for communicating his mystical experiences to his followers. During his lifetime the movement was still a local one, but in the following decades, under his disciples, it spread throughout eastern Europe and was checked only where it encountered savage opposition, as in Lithuania, for example. Hasidism did not challenge the validity of religious law, and except for some minor changes in liturgy and ritual, the accepted body of law and custom was left intact. What Hasidism did introduce was a new overriding religious value — that of communion with God, which was to be achieved either through enthusiasm or contemplation. [Source: Jacob Kat, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Encyclopedia.com]

The Hasidic leader was expected to have attained this “union” and to communicate it to his followers. Thus, a new type of religious leader arose whose legitimation did not stem primarily from his knowledge of the law but from his charismatic qualities. A new “community” was thus formed upon the basis of personal contact and was not bound by traditional territorial divisions. Those who could settle around the leader did so, while those who could not returned regularly to participate in the religious experiences of the community. In the course of time the leader was viewed not only as the guarantor of religious experience but also as a figure whose intervention was essential for the material well-being of the individual. The followers who gathered around provided for his support and that of his household, which often took on the dimensions of a court. And as in courts, the succession tended to become hereditary. The new religious leadership did not supplant the traditional rabbinical type, but it did encroach upon its authority.

Hasidism also had a deep impact upon many nonreligious aspects of life. It lessened the ascetic tendencies in Jewish living and encouraged emotional self-expression in the form of storytelling and song. It also loosened religious and communal disciplines and sanctioned the quiescent attitude toward the demands of practical life. It was a religious movement, but its total impact was to produce a new Jewish mentality.

Hasidic Clothing and Hairstyles

Payesuman Most of the Hasidim wear a special garb, consisting of a girdle for prayer, a long black coat, and fur hat. Beards are generally worn long and earlocks are grown. Hasidic Jews often have beards and long hair like the prophets in the Bible. One famous rabbi never got a haircut because it would have meant removing his yarmulke, which would have obligated him to stop learning.

The identity of Hasidic sects, the origin of the ancestors, their piety and income level can be determined by those with sharp eyes and the correct knowledge by examining the brim width, crown height and fur-type of “streimel”. [

Covered from head to toe in black, Hasidic men wear ankle-length frock coats (“rekel” ) and broad, round-rimmed Fedora-style hats. On the Sabbath and holidays they wear sombrero-style fur hats (“streimel” ). “Ziziths” are ritual fringes that hang below the hems of suits that remind ultra-Orthodox Jews of the Lord’s commandments.

Like conservative Muslim women, Hasidic women are mostly hidden away in the houses. When they do come out their arms, necks. legs and heads have to be covered, usually in black. Some married women shave their heads and wear wigs when they go out. Men and women wear their traditional clothes even during the hottest months of the summer.

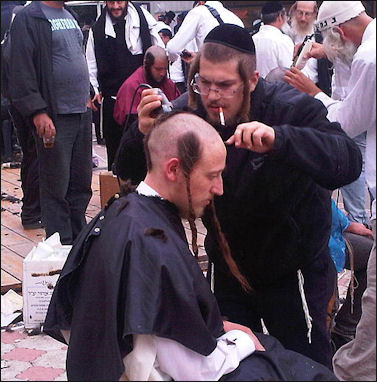

The long strands of braided or unbranded hair that hangs down in front of the ears of Hasidic Jewish men are called "payees” (singular “ payot”, "pe'ot"), or earlocks, which sometimes are tightly curled and other times are thick and straight. When a Hasidic boy is about eight he receives his first ceremonial haircut: his entire head is shaved except a four inch square in front of his ears with a dangling earlock. The ritual is performed during an annual festival of Zefat and is done in accordance with the Biblical command, "Ye shall not round the corners of your heads..."♣

Headgear is very important in defining one’s identity. Moroccan Sephardim wear multicolored embroidered caps. Modern Orthodox Zionist favor small knitted “kipa”, or scullcaps. The followers of the late Lubavitcher Rebbe Menachem Schneerson sport felt fedoras. The identity of Hasidic sects, the origin of their ancestors, their piety and income level can be determined by those with sharp eyes and the correct knowledge by examining the brim width, crown height and fur-type of “shtreimel”, the sombrero-style hats worn by Hasidic men on the Sabbath and holidays. [Source: David Remnick, The New Yorker]

Customs of Hasidic Jews

Hasidic Jews have a belief that has been described as passionate superstition. The painter Marc Chagall once said that Hasidic Jews in his home town used to believed "behind every blade of grass stands an angel urging it on: Grow! Grow!”

Hasidic girls Describing a group prayer session, the sister of a Hasidic Jew wrote in Newsweek, The rebbe “began to slice the air feebly with karate-chop waves of the right hand, turning toward each member of his flock standing before him. The Hasidm leaned from the benches and chopped back feverishly, eager to catch the rebbe’s glance and receive his blessing...All around me, Hasidm began to chant with joy. The sound rolled over me like the blast from a great church organ...We began to swayback and forth...It was impossible not to feel stirred by such emotion.”

Sabbath meals among Hasidic Jews are ritualistic events with multiple layers of meaning, often incorporating re-enactments of ritual sacrifice and deep love for other Jews. A meal sometimes ends with a rugby-scrum-like surge towards an esteemed rabbi to grab food that has been touched and blessed by him. During a Yom-Kippur-eve ritual Hasidic Jews wave a chicken over themselves and their families in the belief that their sins will be transferred to the chicken. After the bird is killed and plucked it is made into a soup.

Ritual immersion plays an important part in Hasidic life. A mikvah is a special bath for purification used by women after menstruation. Lubavitch men immerse themselves in mikvahs to cleanse themselves spiritually before walking to morning prayers. One rabbi told National Geographic, “Even the mundane things we do, form how we walk in the streets to how we interact with others, are meant to be infused with holiness.” [Source: Carolyn Drake, National Geographic, February 2006]

Satmars — One of the Largest Hasidic Sects

With more than 100,000 strong, the Satmars are the world’s largest Hassidic sect. They follow an interpretation of Jewish law that is exceptionally strict even in the orthodox world. Their policy is of unrelenting anti-Zionism; like other ultra orthodox they don’t recognize the state of Israel. However, unlike other extreme orthodox groups, they actively oppose its very existence. They are based in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, with a major outpost in Kiryat Joel, in Orange County, New York.[Source: ruthfilms.com]

Satmars are well-know for their anti-Zionist views. Clyde Haberman wrote in the New York Times: Satmar is not opposed to Jews living in the biblical land of Israel. But the existing state of, by and for Jews is another matter. Since Jews do not believe that the Messiah has yet come, the creation of this state by the Zionists is, for the Satmars, an abomination that can only delay God's redemption of the Jewish people.

“In Israel, Satmar's numbers are not overwhelming -- 3,000 or 4,000 people, according to some estimates. But the sect has influence well beyond those figures, and it is supported by a well-financed, politically active organization in the United States with important centers in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn and in Kiryas Joel, a village near West Point, N.Y.

Satmar is the dominant force in Eda Haredit, a coalition of Hasidic groups in Israel that are militantly opposed to the State of Israel. By contrast, a well-known rival, the Lubavitcher sect, is strongly pro-Zionist; its leader, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson has come out strongly against any Israeli compromise with the Arabs on territory.

Otherwise, on most theological matters -- and in their members' physical appearance -- it is often difficult for outsiders to distinguish the various Hasidic groups from one another. One element in Eda Haredit, a small sect called Naturei Karta, is so anti-Zionist that it has solidly allied itself with Mr. Arafat and his Palestine Liberation Organization. In fact, when Mr. Arafat issued his celebrated call last month for a "jihad" -- in Arabic, a holy war or struggle -- to liberate Jerusalem for Muslims, he cited Naturei Karta as a shining example of Jews who "are refusing to recognize the State of Israel and are considering themselves as Palestinians."

For the Satmars, Naturei Karta goes too far. The sect is not opposed to talking peace with Arab states. Indeed, a Satmar hero is Yaakov Yisrael De Haan, a fervent anti-Zionist who had contacts in the 1920's with Arab nationalist leaders and who is said to have been killed 70 years ago by the Haganah, the underground military of the Jewish settlement in pre-state Palestine.

Rabbi Moses Teitelbaum, Leader of the Satmars

Rabbi Moses Teitelbaum was the spiritual leader of the Satmars. In June 1994 he returned to Jerusalem after a long absence due to his anti-Zionist views. The New York Times reported: Tens of thousands of people, both the ardently loyal and the discreetly respectful, poured into the streets to welcome back this long-absent leader....The focus of adulation was Rabbi Moses Teitelbaum, spiritual leader of the Satmar Hasidic sect, who came to Jerusalem from Brooklyn to tell his disciples here that they must stay true to their beliefs. Among those tenets: total opposition to the Zionist entity whose soil they tread, for they believe it is a sin to create a Jewish state until after the Messiah comes. [Source: Clyde Haberman, New York Times, June 8, 1994]

Jerusalem is hardly unaccustomed to high-profile visitors. But the city and its Zionist police, who were left to cope with inevitable traffic jams, were turned on their collective ear by the 82-year-old Satmar Rebbe, or Grand Rabbi. By some estimates, he drew as many as 100,000 people when he went to the Mea Shearim neighborhood, a Hasidic stronghold that had been festooned for weeks with banners and wall posters welcoming "the king." Streets became surging rivers of men in black hats and caftans, of women in head scarves and long dresses. Many waited hours just for a glimpse of the Rebbe, women standing behind rope barriers and kept apart from the men, as they are in synagogues and other religious places. The turnout was so large that some abandoned false modesty. Without hesitation, Yehuda Meshi-Zehav, logistical coordinator for Rabbi Teitelbaum's two-week trip, pronounced this "royal visit" to be the "biggest welcome since King David moved his capital to Jerusalem from Hebron" -- 3,000 years ago.

While Kiryas Joel is far from rich, the sect has money. As a sign of the wealth, Rabbi Teitelbaum arrived today from New York in the company of 2,000 followers who had filled five jumbo jets (none of which belonged to El Al, the Zionist state's national carrier). Some 350 raffle winners got to fly on the Rebbe's plane. One New York loyalist, Elazar Kastenbaum, paid $500,000 to help cover the trip's costs, and his reward was to drive Rabbi Teitelbaum up winding hills to Jerusalem from the national airport named after the legendary Zionist figure, David Ben-Gurion.

For those interested in such matters, the honor cost Mr. Kastenbaum about $17,000 a mile. "But the honor isn't in the driving," Mr. Meshi-Zehav said. "The honor is in whom he's driving." The Rebbe himself came with $5 million to distribute among individuals and institutions of his sect, which was founded by his uncle, the late Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum, and which takes its name from the Romanian town of Satu Mare. Rabbi Moses Teitelbaum became Grand Rabbi after his uncle's death in 1979, and he last came to Israel 11 years ago.

Sex Life of Hasidic Jews

In some Hasidic sects, males over the age of nine can not touch members of the opposite sex other than their wives and they are not allowed to touch them in public. Some married couples sleep with a bed sheet between them that has a hole to allow sexual relations.

According to “Growing Up Sexually: “ These Jews have been located among the most sexually “repressive” in the world. “Since the sexes have been separated since childhood the anticipated sexual encounter following the marriage ceremony is a matter of great moment and anxiety”. “Ideally, neither men nor women have any sexual experience before marriage; because this area is rarely ever discussed, however, little information on the subject exists. On the Shabbes some Rebbes often obliquely caution parents to guard their children from committing the sin of masturbation. […] The Hasidic girl is carefully shielded from boys from her early years until her marriage. Matters relating to sex are never discussed. There is no preparation for the bodily changes that take place at puberty, nor is there much exchange between mother and daughter concerning marital relations”. Still, young couples “are warned that the performance of the sexual act must be in the line of duty along with other religious observances, but at no time should it serve as an “abominable deed of passion and lust” [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Poll states: “Both bride and groom have received instruction from their respective parent of the same sex regarding sexual experience, in spite of the fact that parents assume their youngsters to have acquired the necessary information from reading and hush-hush conversation with peers. […] Available evidence indicates little if any indulgence in masturbation, though transgression does not seem to meet with severe sanctions beyond strong disapproval or slight slapping of the offender’s hands. Similar behavior was observed with regard to heterosexual play, except that in this case control is accomplished by strict separation of the sexes, both within and outside the home, a separation that begins almost at birth.. […] Boys are gradually introduced to the subject of sex in school, where, accompanied by a degree of embarrassment, they encounter it in the Bible, the Talmud, and the law codes. Girls, on the other hand, are formally kept ignorant until immediately before marriage”.

Against all odds, the author found “traces of autoerotic behavior among boys between puberty and marriage, but it is impossible to even guess at its extent”. Thus, there appear to be few if any data on children’s sexual experiences. “It must be noted that hasidic boys are, for the most part, separated from women (other than their immediate family members) starting at the age of three. Their contact with women, therefore, is limited. After Bar Mitsva (thirteen years of age), their daily routine involves sitting and studying for most of the day. No time is allotted for exercise or any other sort of physical release, which is seen as glorifying the body and therefore forbidden. Even non-Hasidic teenagers have trouble maintaining a healthy, balanced attitude toward their bodies and growing sexuality”.

Hasidic Marriages and Women

According to National Geographic: Marriagea are often arranged by match makers or relatives. Couples date and seek the rebbe’s blessing at his grave site. Weddings often occur when the married couples are young. Mothers of the bride and groom often stand next to the couple when they tale their vows. Marriage and wedding customs vary from sect to sect. At engagement parties various Hasidic groups gather and mingle and men swap their distinctive hats to symbolize unity. “”We have different customs and in some our philosophies and dies, but we are all Jewish,” one Lubavitcher told National Geographic. [Source: Carolyn Drake, National Geographic, February 2006]

Men and women often sit in separate groups at social events. “We set very clear boundaries,” one Lubravitch woman told National Geographic,“It’s in the spirit of modesty.” Women dress with elbows and knees covered. Married women wear wigs or shawls over their hair. “We keep what’s precious hidden.” the Lubravitch woman told National Geographic. “There’s a sense of respect, of sacredness, about women.” Girls are allowed to expose their hair. Many attend yeshivas. [Source: Carolyn Drake, National Geographic, February 2006]

Lubravitch women often have many children and take their roles as mothers seriously. One told National Geographic, “It’s the mother who says morning prayers, who teaches the blessings, who shapes the values at home...In the Torah women are called “akert ha-bayit”, the foundation of the home. That doesn’t mean washing dishes. It’s educating our children in everything we think about life. That’s the nature of what a mother is.

Married Orthodox women wear wigs in public, reserving the sight of their natural hair for the sole eyes of their husbands. Such modesty comes at a price: A sheitel, Yiddish for wig, with a natural look can cost upwards of $1,000. There are hair stylists that a shop called Raizy's in Crown Heights. In some sects, after a wedding the bride shaves her hair and covers her head so as not to temp other men.

Wedding Dances of Hasidic Jews

At Hasidic weddings, among some sects, men dance with other men in line dances. George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “Hassidic Jews have a variety of specific dances for weddings, including the first dance after the ceremony, the knussen-kaleh mazel tov (bridegroom and bride, good luck); the patch tants (clap dance), an initiation dance for the bride; and the koilitch dance. The knussen-kaleh mazel tov is a farandole, danced in a snake-like line with the male relatives holding the bride’s veil, one on each side of her. In the other hand, they hold a handkerchief to which the other guests hold, forming a line. This dance is also known as a mitsveh (precept) dance. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

The patch tants is performed by the married women, who circle around the bride with the handkerchief held downward; during a grand chain (a right and left chain movement), the bride joins in, thus becoming one of them. Although dancing at weddings is generally a communal activity, there were also some solo or display dances performed for the couple, such as the koilitch dance — the dancer holds a loaf of white braided bread (khaleh) to signify that the couple’s home should never be without bread — and a dance performed by a beggar, who is specially invited as the couple’s first charitable act.

The dance of the kazatskies features the oldest male relative dancing to express his joy at the wedding and to demonstrate that he still has the strength to do so. During his performance, a female dancer, waving a handkerchief, dances a circle round him. The mothers-in-law may also dance the beroiges tants. At Orthodox Jewish weddings, the celebration room is divided into male and female halves so that the sexes do not actually dance together.

Hasidic Jews, Ecstasy and the Diamond Business

Much of the trade in large carat diamonds in the United States is controlled by Hasidic Jews. Andrew Cockburn wrote in National Geographic, The diamond businesses "revolves around personal contacts and connections, thrives on rumor and gossip and cherishes secrecy. Multimillion -dollar deals are clinched with a handshakes and the word “ mazal” , Hebrew for "good luck." Van Bockstael told National Geographic, "Nothing is what it seems in the diamond business, and half the time you don't even know if that is true."

The diamond business is regarded as a tough nut to crack. A Tel Aviv diamond merchant told the New York Times magazine, “The diamond company is usually a family company. People accumulate wealth slowly, over generations.” Many diamond businesses have tight security. Some have systems in their offices that photograph and fingerprint every person who enters.

Ecstasy Couriers to the United States have included Hasidic Jews, middle-class Texas families and Los Angeles strippers. Young Hasidic Jews, recruited because they were believed to arouse little suspicion by customs inspectors, reportedly have been given $1,500 each for carrying 30,000 to 45,000 pills in their suitcases.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2024