Home | Category: Jewish Sects and Religious Groups / Jewish Sects and Religious Groups

LUBAVITCHERS AND CHABAD-LUBAVITCH

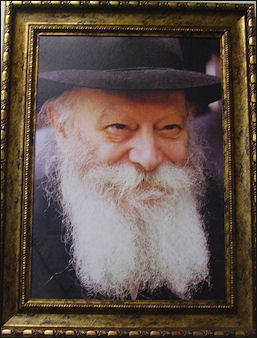

Rabbi Schneerson Chabad-Lubavitch is a Hasidic Branch of Judaism with Kabbalist roots. Founded in Belarus in the 18th century, it has 90,000–95,000 adherents and 3,000 organizations in 75 countries whose goal is to prepare their host cities for the coming of the Messiah. In the meantime Chabad Houses provide religious support and community services for Jewish expats. Members of sect are active in the former Soviet Union, setting up Jewish schools, community centers and orphanages.

Lubavitchers are named after Lubavichy, a town near Smolensk, Russia, where the movement was based from 1813 to 1915.

Chabad come from the Hebrew words for wisdom, comprehension, and knowledge. The group is now headquartered in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. It has been said its outreach programs are meeting the spiritual needs of many Jews eager to reconnect with their faith.

Chabad-Lubavitch's popularity and strength is mainly because of Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the grand rabbi and spiritual leader of the Lubavitch movement from 1951 until 1994. Schneerson, still fondly called the rebbe by his devoted followers, died in 1994 without naming a successor. His image and teachings remain ubiquitous omnipresent in the Lubavitch community. [Source: Carolyn Drake, National Geographic, February 2006]

Jonathan Mahler wrote in the New York Times: Lubavitch is insignificant in terms of the global Jewish population...but it plays an outsize role in worldwide Jewish life. Unlike other, insular Hasidic movements, the Lubavitch credo, articulated repeatedly by Rebbe Schneerson himself, calls for encouraging secular Jews to become more observant. Between its emissaries and far-flung outposts (in 2002 alone, Lubavitch opened 34 Jewish schools around the world), the movement has almost certainly done more to promote the growth of Judaism than any other organization. As of the early 2000s, the Lubavitch movement was very strong. “Its 2002 budget was close to $1 billion, and it continued to open new schools, synagogues and Jewish outreach centers all over the world. [Source: Jonathan Mahler, New York Times, September 21, 2003]

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Rebbe: The Life and Teachings of Menachem M. Schneerson, the Most Influential Rabbi in Modern History” by Joseph Telushkin, Rich Topol, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Holy Days: The World Of The Hasidic Family” by Lis Harris Amazon.com ;

“The Gerus Guide - The Step By Step Guide to Conversion to Orthodox Judaism” by Rabbi Aryeh Moshen Amazon.com ;

“How to Run a Traditional Jewish Household” by Blu Greenberg Amazon.com ;

“Conservative Judaism” by Behrman House Amazon.com ;

“Modern Conservative Judaism: Evolving Thought and Practice" by Rabbi Elliot N. Dorff, Rabbi Julie Schonfeld Amazon.com ;

“Reform Judaism: A Jewish Way of Life” by Charles A. Kroloff Amazon.com ;

“A Life of Meaning: Embracing Reform Judaism's Sacred Path” by Rabbi Dana Evan Kaplan Amazon.com ;

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com ;

“Judaism: History, Belief and Practice” by Dan Cohn-Sherbok Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Rabbi Schneerson

Menachem Mendel Schneerson was the seventh and last leader of Lubavitch. He died in Brooklyn in 1994. Many of his followers believed that he was the Messiah or kind of pre-Messiah. Schneerson’s office receives more than 1,000 letters day requesting blessings. Among the things Schneerson encouraged parents to do was put blessings such as psalms in the cribs of newborn infants.

A number of miracles have been attributed to Schneerson. In July 1992, for example, the daughter of a woman diagnosed with stomach cancer asked Schneerson for a blessing and was told to put mezuzas through her house, light Shabbis candles and perform good deeds. The mother did all things. Three days later when a biopsy was performed no cancer was found. Her doctor said, “Someone’s prayers were answered.” .

Carolyn Drake wrote in National Geographic: The late Lubavitch rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson lit that fuse for thousands. A small, vocal faction of Lubavitchers believe that Schneerson is the Messiah and revere him as such. But most simply honor the memory of the man who helped energize a religion devastated by Hitler and Stalin. Born in Ukraine in 1902, Schneerson arrived in the United States in 1941, devout and driven. He belonged to the Orthodox Chabad-Lubavitch group. [Source: Carolyn Drake, National Geographic, February 2006]

Growth of Lubavitch Under Rabbi Schneerson

The Lubavitch group was relatively small and little known when Schneerson became rebbe in 1951. During his 43-year tenure he pioneered a system of shluchim, or emissaries, charged with going out into the world to open Chabad centers, spreading knowledge of the Torah and Judaism. Some feared that the Lubavitch movement would dwindle after the rebbe's death in 1994. But today there are more than 3,000 centers in 70 countries — nearly half of them founded after Schneerson's death.

Jonathan Mahler wrote in the New York Times: Although Schneerson's predecessor had escaped to Brooklyn during World War II, many of his followers had been trapped in Europe. This meant that the rebbe inherited a movement decimated by Hitler and Stalin. In the 1950's,Schneerson set about rebuilding Lubavitch in a small section of Crown Heights. By the 1960s there were thousands of Lubavitchers living in Crown Heights, and thousands more coming every week to hear Schneerson's stirring sermons. The rebbe himself rarely left Brooklyn, but he sent emissaries, a sort of Jewish Peace Corps, into the darkest corners of the world to rekindle the embers of Judaism. [Source: Jonathan Mahler, New York Times, September 21, 2003]

Schneerson's reputation soon transcended the movement, yet even as his fame grew and it became almost impossible to get an audience with him, Chaim Meyer Lieberman, a follower, told the New York Times he felt a close connection to his rebbe. ''He took a personal interest in my life,'' he said. As the youngest of his 17 children, a 4-year-old, is doing laps around the room and shrieking.

According to National Geographic:Like all religious groups, this one has its detractors, its dropouts, its dark episodes. Schneerson sparked enormous controversy in his day. He supported a strict interpretation of the Torah, preaching that only those born to a Jewish mother or converted by Orthodox rabbis could earn Israeli citizenship — a message that outraged many Jews. In 1991 when a car in the rebbe's entourage hit and killed a black child, some members of the black community in Crown Heights became enraged, and violence erupted. Critics of the movement today deride perceived restrictions on women and the cultlike devotion of the messianic faction.

Lubavitcher Missionary Work

Missionary work is important to Lubavitchers. One man who established a Chabad center in St. Thomas, Virgin Islands told National Geographic, “The biggest milestone in the Lubavitch community is when a new couple goes to a community where Jewish awareness is not strong. One Lubavitcher told National Geographic missionary work helps create a holier world that will hasten the Messiah's coming. One Rabbi spoke passionately about bringing Jews back to their faith: "We have to renew that spark." [Source: Carolyn Drake, National Geographic, February 2006]

Chabad-Lubavitch stresses an inclusive approach to religion. A Chabad-Lubavitch rabbi in Tokyo told the Japanese Times, “Chabad is for Jews, but for non-Jews as well. We don’t open solely for Jews, because God created everyone. Most of our friends are Japanese . We’re not trying to covert people. God created many different nations, and they don’t need to bother to change or become kosher.

Chabad-Lubavitch followers are called Chabadnicks, They are regarded as fundamentalists and are much more involved in missionary work, even proselyting, than has traditionally been the norm, among Jewish sects. Chabadnicks have many similar views as fundamentalist Christian and Muslims. They regard homosexuality as a sexual perversion and are anti-abortion. In Israel they support the right-wing Greater Israel party. One of its leaders Rabbi Eliiezer Shach has described Chabad-Lubavitch as the sect closest to true Judaism.

Lubavitch Family Life

Carolyn Drake wrote in National Geographic: Schneerson vastly expanded the practice of sending emissaries out into the world to spread Orthodox Jewish faith. He encouraged wives to participate as emissaries along with their husbands, and advised women to pursue the mission in a distinctly feminine way, offering instruction on how to keep a kosher kitchen, how to follow the laws of family purity, and how to raise spiritual children. [Source: Carolyn Drake, National Geographic, February 2006]

A Lubavitch man's well-worn prayer book hints at his devotion. Reading prayers three times a day is one of thousands of Jewish laws governing all aspects of life. "As Jews, we spend our lifetime trying to follow specific laws and rituals," says Lubavitch spokesman Rabbi Zalman Shmotkin. "We view them not simply as rigid and restricting commandments, but as conduits to tap into the divine."

A father of nine, Rabbi Yosroel Shimon Kalmenson reads bedtime stories to some of his children and nephews at his home in Crown Heights. The books, television programs, and games that Lubavitch children use are infused with Jewish and Hasidic values, which support a traditional interpretation of the Torah.

Honoring Rabbi Schneerson

Carolyn Drake wrote in National Geographic: The faithful feel Schneerson's presence most acutely at his grave in Queens. "It has become a beacon that people flock to," says Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky, a top Lubavitch leader. [Source: Carolyn Drake, National Geographic, February 2006]

Portrait of decorates the side of a "mitzvah tank" — a mobile synagogue — parked in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Lubavitch emissaries, or outreach workers, drive the vehicle to various parts of Manhattan and Brooklyn, where they conduct religious activities and teach less observant Jews about their faith.

Hundreds of people visits Schneerson’s grave every day, which they believe holds the rebbe’s soul. The grave is next to the grave of his father in law and predecessor. The site is covered with written prayers and requests for guidance of blessings. One Lubavitch rabbi told National Geographic, “We believe that the soul never dies. There remain an accessibility, not just in memories, but in fact.

Describing an event honoring Schneerson in 2023, Adam Gopnik wrote in The New Yorker: The Moshiach came to Madison Avenue this summer. All over a not particularly Jewish neighborhood, posters of the bearded, Rembrandtesque Rebbe Schneerson appeared, mucilaged to every light post and bearing the caption “Long Live the Lubavitcher Rebbe King Messiah forever!” This was, or ought to have been, trebly astonishing. First, the rebbe being urged to a longer life died in 1994, and the new insistence that he was nonetheless the Moshiach skirted, as his followers tend to do, the question of whether he might remain somehow alive. Second, the very concept of a messiah recapitulates a specific national hope of a small and oft-defeated nation several thousand years ago, and spoke originally to the local Judaean dream of a warrior who would lead his people to victory over the Persians, the Greeks, and, latterly, the Roman colonizers. And, third, the disputes surrounding the rebbe from Crown Heights are strikingly similar to those which surrounded the rebbe Yeshua, or Jesus, when his followers first pressed his claim: was this messianic pretension a horrific blasphemy or a final fulfillment? Yet there it was, another Jewish messiah, on a poster, in 2023. [Source: Adam Gopnik, The New Yorker, August 21, 2023]

Belief That Rabbi Schneerson Was the Messiah

Many Lubavitchers believe or believed that Schneerson, who died in Brooklyn in 1994 was the Messiah or kind of pre-Messiah. Jonathan Mahler wrote in the New York Times:When the rebbe was alive, just about every Lubavitcher was confident he was the messiah. Because all Lubavitchers consider the messianic era to be imminent, it stands to reason that every generation would believe that its particular rebbe might be the messiah. Even given this predisposition, though, the movement's faith in the messianic potential of Schneerson, who was childless, was always uncommonly strong. This was partly a matter of historical context. When the rebbe took the reins of the movement, the Jewish people had just survived the worst calamity in their 3,000-year history -- a propitious moment for them to be delivered from the sufferings of their exile. [Source: Jonathan Mahler, New York Times, September 21, 2003]

As the years passed, the Lubavitch community became increasingly convinced that their rebbe met all of the requirements, laid out by Maimonides, to be the Jewish messiah. Most significant was his emphasis on outreach. ''Maimonides said the messiah would be a Jewish leader who will 'repair the breaches,''' one messianic rabbi, Eli Cohen, told me, ''or fix that which is missing in Jewish observance, and that's what the rebbe did.'' World events -- specifically the fall of the Soviet Union, which had suppressed the practice of Judaism, and the struggle over Israel -- fanned the community's messianic flames.

The biggest difficulty in trying to figure out what the rebbe really wanted is that he, too, was aware of his movement's image and thus sent different signals to those inside and outside the community. This was more than a mere P.R. gesture. The rebbe seemed to believe that bringing secular Jews back into the fold was a critical part of the process of redemption and was thus understandably wary of scaring people off with messianic zealotry. What does seem clear is that the rebbe was, for many years, eager to quell the tide of messianism when it began to rise. But as he grew older, he became more reluctant to do so. Among the messianists' abiding articles of faith are two videotapes of the rebbe in his later years. One shows him smiling as a crowd of Lubavitchers sing Yechi around him; in the other, he is accepting a petition signed by thousands that identifies him as the messiah.

In the late 80's and early 90's, the rebbe, no doubt increasingly aware of his approaching mortality as well as of his lack of progeny, began speaking more and more frequently about the messiah -- not explicitly nominating himself but nonetheless encouraging a messianic urgency among his followers and even occasionally hinting that the messianic era had already begun.Max Kohanzad was a teenager in the Lubavitch yeshivas during those critical years. He and his classmates spent four hours a day poring over the rebbe's messianic discourses.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Waiting for the Messiah of Eastern Parkway” in the New York Times Magazine nytimes.com

Then Schneerson Dies

Jonathan Mahler wrote in the New York Times: But that consensus was ruptured on the night of June 12, 1994. Lieberman remembers hearing the blare of the horn used to signal the end of the Sabbath. Only the Sabbath had ended hours earlier. The rebbe had suffered a stroke a few months before, and Lieberman correctly feared the worst. [Source: Jonathan Mahler, New York Times, September 21, 2003]

Hustling over to the Lubavitcher headquarters, he saw hundreds of Lubavitchers converging outside. Some wept; others, however, were gleeful, downing vodka, dancing and singing Yechi. Lieberman was stunned. As his grief turned to anger, he spoke to a prominent rabbi in the community, who stood near him. ''How can you stand by here when you see this display,'' he remembers saying to the rabbi, ''and not open up your mouth?''

In the aftermath of the rebbe's death, Max Kohanzad was among the jubilant messianic Lubavitchers whose behavior so appalled Lieberman. ''I spent the entire day with the other yeshiva students singing Yechi and anticipating the actual redemption,'' says Kohanzad. ''What was understood was that this was the day utopia was going to begin.''

Though he'd been sick for years, the rebbe's death came as a shock to the community. Some Lubavitchers, like Lieberman, started the process of accepting the reality that their messiah in waiting was gone. ''Sure I felt disappointment, but you have to move on,'' Lieberman says. ''What can one say other than that life is not always what you want it to be?'' But many clung stubbornly to their faith, insisting that the rebbe never really died or that the process of redemption was under way and that the rebbe would soon return and be revealed as the messiah. ''Exactly how this is going to come about we really don't know,'' Rabbi Cohen says. ''What we do know is that if you open your eyes, you can see that bit by bit it's coming to pass.''

Lubavitch Messianists

Mahler wrote in the New York Times: Thirty-five years old and skinny, with long kinky black hair and a Frank Zappa goatee, Baruch Thaler left the Lubavitch movement several years ago, but his mother, stepfather and five siblings are all still very much a part of it. Making one of his occasional trips to Crown Heights on a recent afternoon, Thaler takes me to meet his mother. ''This is what a messianic house looks like,'' he says, ushering me into the living room of his family's semiattached home. He is wearing a white shirt, untucked, black jeans and sneakers and a black knitted yarmulke that he has put on for the occasion. [Source: Jonathan Mahler, New York Times, September 21, 2003]

On the bookshelf is a stack of Beis Moshiach magazines, the local messianic weekly, as well as the Igros Kodesh, a collection of the rebbe's letters that messianists use for guidance by flipping to a random page and reading the rebbe's words as an answer to something about which they need advice. Thaler's mother, Rachel, 57, with blue eyes and braces on her teeth, comes down the stairs in traditional Orthodox garb — a brown wig and ankle-length skirt — and takes a seat next to her son on the couch. It is one of the peculiarities of the movement that for every Lieberman, an Old World Hasid, there is a New Age seeker like Rachel Thaler, who was a lapsed Jew living on a macrobiotic commune in upstate New York when she discovered Lubavitch in the early 1970's.

As with many fundamentalist faiths, whose most zealous practitioners tend to be converts, the most ardent messianists were not born into Hasidism but are rather ba'al teshuvah, or returnees to the faith, like Rachel. ''God recreates the world every second,'' she says, explaining her messianic faith to me. ''It's like a movie — every frame can be totally different.'' Later I ask Thaler about his mother's messianism. ''Does believing in a man hanging on a cross make any more sense?'' he replies. ''Once you're in that mind-set, it's not a great wonder that you have people like my mother who seek the answers to life's crucial decisions based on opening a book.''

Messiah Party at Lubavitch Headquarters

Jonathan Mahler wrote: The synagogue in the basement of the Lubavitch headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, is the closest thing to holy ground for the Hasidic movement, though with its peeling paint, dirty linoleum floors, wooden benches and unidentifiable odor, it feels more like a junior-high-school cafeteria than your average Jewish sanctuary. But at a little before 10 p.m. on a recent Friday night, the place is thick with spirituality. Small clusters of bearded men bob furiously in prayer, while a smattering of women watch from behind the plexiglass in the balcony above. [Source: Jonathan Mahler, New York Times, September 21, 2003]

“In the center of the room, a group of about 25 men are dancing hypnotically in a circle. A few bounce little boys on their shoulders as they chant a single phrase over and over: Yechi adonenu morenu verabbenu melech hamoshiach leolam voed. A middle-aged man standing near me catches my eye. Like everyone else here, he's wearing the Lubavitch uniform — black wool suit, white shirt and black fedora. When he opens his mouth to speak, I expect his words to come out coated in Yiddish. Instead, they're pure Brooklyn. ''That's the No. 1 hit in Crown Heights,'' he says, stroking his big red beard and grinning.

“It looks almost like a rain dance, only instead of precipitation, these Lubavitchers are trying to hasten the arrival of the messiah. There's just one problem. The words of the accompanying song — ''May our master, teacher and rabbi, the king messiah, live forever'' — refer specifically to a man who died nine years ago: Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson... The Yechi, as it is known, is sung as a demonstration of faith that their beloved rebbe will be back soon — rising from the great beyond in a manner more befitting Jesus Christ than the savior of the Jewish people.

Lubavitch Anti-Messianists

Mahler wrote: If Yechi — ''May he live'' — is a demonstration of faith to some, it borders on a profane outburst to others. A swath of Lubavitchers are not only unwilling to utter the Yechi; they also refuse to be present in synagogues or at gatherings where it is chanted. To understand the concern of these so-called anti-messianists, consider that only a few men in Jewish history have been revered as the messiah after their deaths. One was Jesus. Another was Sabbatai Zevi, who won hundreds of thousands of followers across Palestine and Eastern Europe after publicly declaring himself the messiah in 1665. (Zevi's death was, relatively speaking, a small challenge to his adherents, who had already chosen to stick by him after his conversion to Islam.)

For the anti-messianists, their messianic brethren present a public-relations disaster of epic proportions. They worry that their Hasidic movement, which is 300 years old and has survived pogroms, Communism and the Holocaust, will become confused with a cult. What's more, they can hardly ignore the obvious Christian overtones of messianism: what kind of Jews believe in a second coming?

In 1968, Lieberman participated in the building of the synagogue in the basement of 770, which was formerly a medical clinic. Today Lieberman refuses to pray there during the Sabbath, when the messianism reaches its most fevered pitch, opting instead for one of the community's nonmessianic synagogues. ''It's such an abomination,'' he says in disgust. ''My blood pressure goes through the roof when I walk in there.''

But there is no question that the continuing messianism has the potential to cause significant attrition among the next generation. It is difficult enough to keep young people in a small enclave in the heart of Brooklyn insulated from the temptations of the secular world without also asking them to believe that a man who died nine years ago is about to return and redeem them.

Lubavitch Messianists Versus Anti-Messianists

Mahler wrote: What started as a fissure between the community's messianists and anti-messianists has gradually opened into a canyon, with each side insisting that it is the true heir to the rebbe's vision. Over the years, the conflict between the two factions has also become one of propaganda, with rival publishing houses, magazines and bookstores. There are also endless semantic distinctions between the two factions, the most common of which is that anti-messianists write ''Of Blessed Memory'' after the rebbe's name, while messianists insist on ''Long Live King Messiah.'' There is even a Lubavitch version of the school-prayer debate, over whether the yeshivas should encourage students to sing Yechi. (Some do, some don't.) [Source: Jonathan Mahler, New York Times, September 21, 2003]

The messianists, who say they believe they can hasten the rebbe's return by persuading as many people as possible that he is the messiah, promote their agenda in the streets, proselytizing regularly in non-Lubavitch neighborhoods, approaching strangers and prodding them to recite Yechi. Their calls are echoed by two messianic talk-radio shows, ''Living With Moshiach'' (the Hebrew word for messiah) and ''Moshiach in the Air.''

The messianists are clearly straying from Jewish norms with their belief in a resurrected messiah. And yet, they are also reclaiming an abandoned element of the religion; Judaism, after all, was the original Western messianic faith. Still, for most Jews today, observant and secular alike, the very concept of a messiah has become, at most, a metaphorical one. And the idea of one Jew trying to persuade another one that a deceased Brooklyn rabbi is the messiah is repellent. ''I'm embarrassed to tell you some of the things I've seen,'' Lieberman says. About a year ago, he watched in humiliation as the police were called in to confront a group of Lubavitchers who were camped out in front of a synagogue in Borough Park, Brooklyn, trying to persuade members of another Hasidic community to accept the rebbe as their messiah.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024