Home | Category: Jews in the Greco-Roman Era

UNREST AMONG THE JEWS IN THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE

Medieval vision of the

coming of the Jewish Messiah There were many uprisings by the Jews during the period of Roman rule. In the A.D. 1st century there were conflicts between the Essenes, the Pharisees and the Hellinized priests that ruled the Temple. Messianic fervor led to several uprisings that eventually forced the Romans to put down two major Jewish revolts, in A.D. 70 and A.D. 125, the destroy the Jewish Temple and disperse the Hebrew population. It has been suggested that if the Jews hadn't revolted there would have been no Jewish diaspora and history would have been very different.

According to the BBC: “This was a period of great change — political, religious, cultural and social turmoil abounded in Palestine. The Jewish academies flourished but many Jews could not bear being ruled over by the Romans. During the first 150 years CE the Jews twice rebelled against their Roman leaders, both rebellions were brutally put down, and were followed by stern restrictions on Jewish freedom.” [Source: BBC]

Holland Lee Hendrix told PBS: “The first thing I think I would say about the situation of Judea at the time of Jesus, is that it really is a burgeoning economy. It's a new world because of the arrival of Rome, and because of the accomplishments of Herod's rule. But at the same time, these very accomplishments produce some tensions. We could probably think of it best if we think of it as almost two intersecting axes. The first is a series of religious tensions, many of them focusing on the Temple. The Temple is both the center of continuity, it's the center of devotion, and yet it can be the center of religious controversy and apocalyptic expectation or sectarian identity. Such as that we see at ... at Qumran, and among the Dead Sea Scrolls. [Source: Holland Lee Hendrix, President of the Faculty Union Theological Seminary \=/ Frontline, PBS, April 1998 \=/]

“On the other side, there is the political and socioeconomic tension that we see reflected in the rise of social banditry. Let's remember that Josephus actually mentions over a dozen of these rebel bandit kinds of figures, like Judas the Galilean and The Egyptian. All the way from the time from Herod, himself and going down to the time of the first revolt. And at least, according to Josephus, there's a kind of increasing sense of political unrest that comes with them. Now, this political tension though, is also fueled by religious ideas and expectations. And here again, Jerusalem and the Temple seem at times to be a kind of focal point of their ideas. \=/

RELATED ARTICLES:

FLAVIANS (RULED FROM A.D 69-96): TITUS, DOMITIAN AND THE JEWISH WARS europe.factsanddetails.com

SECOND TEMPLE OF JERUSALEM (HEROD'S TEMPLE) africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIFE OF THE JEWS AROUND THE TIME OF JESUS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

JEWISH WARS AND REVOLTS AGAINST ROME africame.factsanddetails.com

MASADA: HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGY, MASS SUICIDE africame.factsanddetails.com

SIEGE OF JERUSALEM BY THE ROMANS IN A.D. 70 africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; Bible and Biblical History: ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Bible History Online bible-history.com Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Jewish History: Complete Works of Josephus at Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org ; Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Christianity: BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Jewish War” by Flavius Josephus , Betty Radice, et al. (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“The Antiquities of the Jews” by Flavius Josephus, Allan Corduner, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Masada - The Complete Epic Mini-Series” (DVD) Amazon.com ;

“The Jewish Revolt AD 66–74" by Si Sheppard and Peter Dennis Amazon.com ;

“Jews In The Roman World” by Michael Grant Amazon.com ;

“The Jews among the Greeks and Romans: A Diasporan Sourcebook”

by Professor Margaret Williams Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jewish People During the Babylonian, Persian, and Greek Periods”by Charles Foster Kent Amazon.com ;

“The Herods: Murder, Politics, and the Art of Succession”

by Bruce Chilton, Paul Heitsch, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Herod's Temple: A Useful Guide To The Structure And Ruins Of The Second Temple In Jerusalem” by Michael Lustig Amazon.com ;

“An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel, and Jesus” by Lester L. Grabbe Amazon.com ;

“Between the Testaments: Pharisees, Sadducees and Essenes” by Robert C. Jones Amazon.com ;

“The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English: Seventh Edition”by Geza Vermes (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

“The Story of the Jews” Volume One: Finding the Words 1000 BC-1492 AD by Simon Schama (Author) Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Unrest and Messiahs

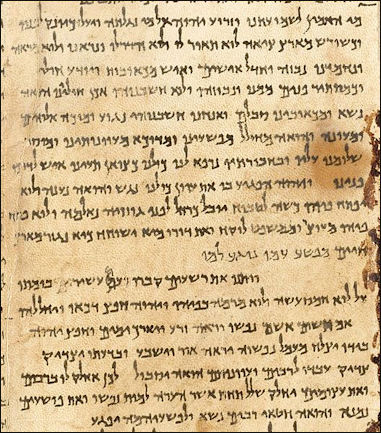

Dead Sea scroll written by the Essenes Jesus was born at a time of social unrest when many Jews were interested in the coming of a Messiah. The unrest can be traced back to the Maccabean revolt in 167 B.C., a nationalist Jewish rebellion against Greek rulers. Many young Jewish men died as martyrs. The Maccabean revolt set off a long period of chaos, social upheaval and expectations of a Messiah.

Messiah literally means the “anointed one” in Hebrew, and was widely understood to mean “King of the Jews." In Jesus's time Jews regarded the ideal Messiah as a redeemer or Davidic king, who take the faithful to a peaceful world, far different from the chaotic one that people lived in at that time. As a consequence of this religion began to focus more on the destiny of the individual, meting out justice in way that righted injustice of the world and dealt with the afterlife. From out of this grew the concept of a Judgment Day, resurrection and salvation.

Jews, in Jesus's time, believed that the Messiah was more likely to be a strong military leader than a gentle, moralizing preacher. The prophet Isaiah predicting that the Messiah would be a "Prince of Peace" who conquered the Assyrians "like the mire of the streets," reduced Damascus to "a ruinous heap," transformed Babylon into a city inhabited only by owls, satyrs and other "doleful creatures," and in Egypt “turn everyone against his neighbor, city against city, and kingdom against kingdom."

The prophet Jeremiah expressed similar sentiments. According to him, God said that the Philistines "shall cry and all the inhabitants of the land shall howl," the Egyptians "shall be satiate and made drunk with their blood," and the daughters of Ammon shall "be burned in fire" when the Messiah comes.

Pharisees, Sadducees and Essenes

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “The Pharisees, whose name may have meant "separatists," were a group of religious lay leaders committed to the purification of Judaism through meticulous observance of moral and ceremonial laws. They supported the temple cult but were most uneasy about the usurpation of the high priesthood by one of non-priestly caste. More often they were identified with synagogues, the local autonomous gathering places of the masses, where prayer and study were conducted. In addition to the study of the scriptures, the Pharisees emphasized the teachings of the elders or oral tradition as a guide to religion. They professed belief in the resurrection of the body and in a future world where rewards and punishments were meted out according to man's behavior in this life. They believed in angels through whom revelations could come, and later were to develop a belief in a Messiah.3 They tended to view alliances with foreigners with suspicion. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“The Sadducees were pro-Greek, aristocratic priests, whose interests were centered in the temple and the cultic rites. Their name was probably derived from Zadok, the famous priest of the time of David and Solomon (II Sam. 8:17;. 15:24; I Kings 1:34). Because the offices of high priest and governor were combined, the Sadducees tended to be deeply involved in high-level politics. Politically, they were committed to independence and to the concept of the theocratic state, as were most Jews. Although they were opposed to foreign domination, they did not object to the introduction of foreign elements into Jewish life. Like the Pharisees, they stressed the importance of observance of the Torah, but they rejected the authority of oral tradition. When confronted by situations not covered in the Torah, they enacted new laws. They rejected the Pharisaic doctrine of a resurrection and a future life and held to the older Jewish belief in Sheol. Nor did they accept the belief in angels.

The Essenes were a breakaway, apocalyptic Jewish sect that lived around the Dead Sea. Regarded as the authors of the Dead Sea scrolls, they moved to the desert to await the Messiah and believed in baptism and redemption. Since their monasteries were so close to John's baptismal site many believe they were early purveyors of Christianity. Most everything that is known about the Essenes has been derived from the Dead Sea scrolls.

See Separate Article: PHARISEES, SADDUCEES AND ESSENES africame.factsanddetails.com

Jewish Guerilla Movements

At the time of Jesus's birth, the Holy Land was crawling with militant Jewish groups engaged in a prolonged guerilla-style warfare against the Roman army. The districts of Palestine, where Jesus lived and worked were major centers of insurgent activity.

Militants Jewish groups and “bandit-guerrillas” were active in the decades before the birth of Christ and they continued being active decades after his death until a full scale Jewish revolt in A.D. 68 when a leader named Manahem took control of the temple area by driving out the Roman troops and executing the high priests. Six Roman legions were required to put the revolt down. Josephus chronicled five major Jewish military messiahs, not including Jesus or John the Baptist, between 40 B.C. and A.D. 73.

The Romans referred to the Jewish insurgents as bandits even though most of their targets were absentee landlords and tax collectors. They were also sometimes called "zealots" (a reference to their zeal for Jewish law and the promise of God's covenant). Bandit-guerrillas who were caught were often crucified or beheaded in public.

Tactics of the Jewish Guerilla Movements

Abatur at the scales

an image with Essenes roots? The zealot-bandits practiced guerilla tactics that would have made Mao proud: they seized armories, staged hit and run attacks and assassinations and carried out suicide mission and terrorist attacks on the palaces of important leaders. Many of the fighters lived in caves or mountain hideouts. Some urban guerilla fighter were known as "dagger men," because they carried knives in the folds of their robes.

From time to time these guerilla leaders lead uprisings that were quickly dashed by the Roman military. Herod made a name for himself by ambushing two threatening Jewish leaders. One leader was executed in front of a cave in full view of his wife and seven children. In 4 B.C. Jews angry over the execution of students caught trying to remove a Roman eagle from temple decoration launched a city-wide riot. Eventually some 2,000 Jews were crucified.

A violent protest broke out over the Roman transgression of the Jewish taboo on graven images and the use of temple funds to build an aqueduct to supply the Romans with water for their bathes. During a Passover feast in 50 A.D. a Roman centurion raised his tunic and farted into a group of pilgrims. "The less restrained of the young men and the naturally tumultuous segments of the people rushed into battle," Josephus reported. The Roman infantry was called in and Josephus claimed 30,000 people were trampled to death.

The rebels had a few victories. In A.D. 26, Jews confronted Roman soldiers over the raising of a flag with Caesar's face near the central shrine of The Temple. The Jews bared their necks and dared the Romans to attack them. The result: the flags were taken down.

Edicts of Jewish Rights and Tiberius's Expulsion of the Jews from Rome

Edict of Augustus on Jewish Rights reads: , 1 B.C.: Caesar Augustus, pontifex maximus, holding the tribunician power, proclaims: Since the nation of the Jews and Hyrcanus, their high priest, have been found grateful to the people of the Romans, not only in the present but also in the past, and particularly in the time of my father, Caesar, imperator, it seems good to me and to my advisory council, according to the oaths, by the will of the people of the Romans, that the Jews shall use their own customs in accordance with their ancestral law, just as they used to use them in the time of Hyrcanus, the high priest of their highest god; and that their sacred offerings shall be inviolable and shall be sent to Jerusalem and shall be paid to the financial officials of Jerusalem; and that they shall not give sureties for appearance in court on the Sabbath or on the day of preparation before it after the ninth hour. But if anyone is detected stealing their sacred books or their sacred monies, either from a synagogue or from a mens' apartment, he shall be considered sacrilegious and his property shall be brought into the public treasury of the Romans. [Source: Tacitus, The Histories of Tacitus, trans. A. D. Godley (London: Macmillan, 1898)]

Augustus was succeeded by son Riberius. David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Tacitus relates that in 19 BC Tiberius expelled the Jews from Rome (Ann. 2.85), and forcibly conscripted 4,000 of them for the unenviable task of fighting pirates in Sardinia. But it would be an error to see this as a sign of general antipathy or hostility to the Jews. As Josephus tells the story, Tiberius was angered by the misdeeds of a single Jew who converted a noble Roman lady, Fulvia, and persuaded her to make a large contribution for the Temple at Jerusalem, which he then diverted for his own use (AJ 18.3.5). This suggests that the real problem was not the Jews themselves but their isolated successes in winning converts among the Roman upper class. Suetonius also makes it clear that this action was part of a wider crackdown on foreign, especially Eastern, superstitions. [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

Tiberius

“He abolished foreign cults at Rome, particularly the Egyptian (i.e. the worship of Isis) and the Jewish, forcing all citizens who had embraced these superstitious faiths to burn their religious vestments and other accessories .... Tiberius also banished all astrologers, except such as asked for his forgiveness and undertook to make no more predictions (Suet. Tib. 36). /+/

“Philo says that Tiberius' henchman Sejanus hated the Jews and intended to persecute them throughout the Empire. But in fact what anti-Semitism appears in the pagan sources from the period is almost entirely expressed by Greeks. An area of particular tension between Jews and Greeks was the city of Alexandria, which had attracted a large community of diaspora Jews by virtue of its status as a major trading center. Jews had long been prominent as commanders in the army of the Ptolemies, where they were given special dispensation from fighting on the Sabbath. At Alexandria the Jews enjoyed a privileged legal position. Most were not citizens, but they had a separate citizen body (politeuma) with their own council of elders, assembly, and courts. /+/

Edict of Claudius on Jewish Rights, A.D. 41: Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, pontifex maximus, holding the tribunician power, proclaims: . . .Therefore it is right that also the Jews, who are in all the world under us, shall maintain their ancestral customs without hindrance and to them I now also command to use this my kindness rather reasonably and not to despise the religious rites of the other nations, but to observe their own laws.

Fate of Jews Outside Judea

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “The Alexandrian Jews became the outlet for Greek frustration over the transformation of Egypt and Alexandria from one of the centers of the world in the Hellenistic Age to the capital of an imperial province after Actium. A party of Alexandrian nationalists, led by a Greek named Isidorus, rallied supporters around the banner of anti-Semitism. Prior to the death of Tiberius, the equestrian governor of Egypt, A. Avillius Flaccus, had managed to keep the nationalists under control, at one point even expelling their leader Isidorus from the city. But in early 38, the year in which Flaccus was due to be replaced in Egypt by Macro, he seems to have formed some sort of alliance with Isidorus. The reasons for this are not entirely clear; Philo alleges that Flaccus feared Caligula because Flaccus had supported the banishment of Caligula's mother, the elder Agrippina, and further that Flaccus formed his alliance with Isidorus because he hoped that the Alexandrian Greeks would protect him if Caligula decided to seek his head. Most moderns dismiss this as improbable, especially because Caligula had the opportunity to replace Flaccus in this most important and prestigious of imperial provinces, but chose instead to let him serve out his term. But whatever the reason, Flaccus had become more sympathetic to Isidorus and his party of anti-Semites, and the stage was set for conflagration, touched of by the arrival in Alexandria of M. Iulius Agrippa. [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

“This Agrippa (M. Julius Agrippa, not to be confused with Augustus' friend M. Vipsanius Agrippa), a grandson of Herod, had grown up at the Imperial court in Rome, a hostage of sorts, and counted among his friends both Tiberius' son Drusus and the future emperor Gaius. Imprisoned by Tiberius in 36, Agrippa was released by Gaius upon his accession and named king of one of the two tetrarchies in Judea not being administered by a prefect. On his way to take up this office, Agrippa decided to stop and visit the Jewish community in Alexandria; on the face of it, not an unreasonable move, since the Alexandrian Jews were an important part of his constituency and, as later events proved, Agrippa had ambitions for reuniting Palestine under his own leadership. In Alexandria, a lavish parade through the streets by Agrippa, with his entourage and bodyguard, rubbed the faces of the Alexandrian Greeks in the fact that they were governed by a Roman equestrian, while the Jews were allowed to have a king. Too late, Agrippa realized the damage he had caused and slipped out of the country. /+/

Violence Involving Jews

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Isidorus and his partisans went on a rampage of anti-Jewish violence (a vivid description of the atrocities is provided by Philo, Emb. 120-138). Some temples were burned; in others, statues of the emperor were erected. Flaccus responded by creating the first Jewish ghetto: henceforth, the Jews were confined to one of the five districts of the city. Whether this was an attempt to protect the Jews, or a punishment and an indication that Flaccus held them responsible for the violence, is a matter of debate. But the results were clear enough: disease spread through the overcrowded ghetto, and unfortunate Jews who strayed outside of the limits were burned, torn apart, or trampled by mobs. Some relief came later in 38, when Flaccus was finally deposed and replaced by the much more moderate and diplomatic G. Vitrasius Pollio. The ghetto was abolished and the Jews regained some of the property which had been taken over by the mobs. Both Jews and Greeks sent embassies to Rome; Philo's first-hand account of that embassy is extant. [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

“At the same time as the ambassadors from Alexandria were preparing to make their cases at Rome, more trouble was brewing for the Jews on another front. Early in 40 BC (following Philo's chronology over Josephus's) there was a fracas in a little coastal town of Judea called Jamnia, where Jews and Greeks lived side-by-side. The Greeks set up an altar for the imperial cult, and some Jewish zealots promptly tore it down (Philo, Emb. 30). I say zealots advisedly, because in the usual course of things an altar to the imperial cult should not have been a problem, so long as it was not located on sacred ground; Jews all over the empire saw them every day. Caligula's reaction was typically irrational, and exemplary of his megalomania: to punish all the Jews, he gave orders to the governor of Syria that a gigantic statue of himself should be built and placed in the main Temple at Jerusalem. Fortunately, the governor of Syria, Publius Petronius, understood the Jews better than the emperor did. The Jews would sooner die than allow it. Tacitus suggests that Judea was on the point of rebellion: Then, when Caligula ordered the Jews to set up his statue in their temple, they chose rather to resort to arms. ( Hist. 5.9) /+/

“But this brief notice must be modified with reference to Josephus' account, from which it is clear that in consultation with Petronius the Jewish leadership offered a form of passive resistance; they would die to protect the sanctity of the temple, but they did not threaten to fight for it. In the event neither was necessary. Both Petronius and Agrippa, Gaius's boyhood friend, lobbied the emperor; but before Caligula could reach a decision, either about the temple at Jerusalem or about the Jews and Greeks in Alexandria, he was assassinated. /+/

Caligula, Agrippa and the Jews

Caligula

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Certainly it is tempting to see the roots of the great Jewish rebellion in the events of the last years of Caligula's reign. Undeniably, the threat of Caligula to desecrate the Temple of Jerusalem strengthened the hand of the Jewish nationalists, just as abusive government by corrupt prefects and procurators had in the past, and would again. Yet now, in the early 40's, the prevailing opinion among the leaders of the Jewish community was that peaceful coexistence with the Romans could and should continue. The Jews at Alexandria had taken up arms only against the Greeks; in the embassy, both sides, Jews and Greeks, urged that they were the ones trying to act in the best interests of the Roman empire. From the other side, there is every reason not to believe what Philo asserts, that Caligula was planning a major war against the Jews. The two legions which he ordered Petronius to take into Judea were solely to enforce the erection of the statue. [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

“The death of Caligula might have been expected to bring down his friend Agrippa, but (like his grandfather) Agrippa was a survivor, and he convinced Claudius to let him stay on, and even to increase his dominion. Universally regarded as a good king, Agrippa was scrupulous about observing Jewish customs, while at the same time he pleased his non-Jewish constituents with benefactions, buildings, and games. Unfortunately for the Jews, Agrippa lived on after Caligula for only three years; he was only 54 when he died. Had he survived longer, he might well have gotten the lid firmly on to the still simmering cauldron of Jewish discontent, and averted the terrible tragedy that followed twenty years after his demise. For in 44 Claudius put Judea once more under direct Roman control, and discontent at the subsequent maladministration of the procurators led inexorably to the Jewish War. /+/

Jewish Riots in Alexandria

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “On the news of Caligula's death the Jews of Alexandria seized the opportunity to get revenge for what they had suffered, and themselves embarked on a campaign of terror against the Greeks. The riots had to be put down by Roman troops. Too late, a letter arrived from Claudius: ‘I tell you once for all that unless you put a stop to this ruinous and obstinant enmity against each other, I shall be driven to show what a benevolent emperor can be when driven to righteous indignation. Wherefore once again I conjure you that ... the Alexandrians show themselves forebearing and kindly toward the Jews, who for many years have dwelt in the same city, and dishonor none of the right observed by them in the worship of their god, but allow them to observe their customs as in the time of the deified Augustus. And, on the other hand, I explicitly order the Jews not to agitate for more privileges than they formerly possessed, and in the future not to send out a separate embassy as if they lived in two separate cities.’ [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

“Claudius' letters perfectly capture the perennial problem for the definition of Jewish national identity: was a Jew defined by a tie to a particular place, such as Jerusalem, or by adherence to the Mosaic law? The Jews of the first century AD wanted it both ways, to retain a marked sense of exclusivity and difference no matter where they were. This worked in Palestine itself; elsewhere, it ran directly counter to the trend of Roman imperial society in the direction of cosmopolitanism and universalism, and created the kind of antipathy which led Tacitus to say, “The Jews are extremely loyal toward one another, and always ready to show compassion, but toward every other people they feel only hate and enmity." ( Histories V.5) /+/

“We left the Jews early in the reign of Claudius, having narrowly averted the potential disaster of Caligula's insistence on the erection of a gigantic statue of himself in the temple at Jerusalem. They were poised on the edge of a precipice. The death in 44 of the good king Agrippa I, whose dominion Claudius had confirmed and whose territories he had even expanded, left Claudius a difficult choice. Agrippa's only son, Agrippa II, was at the time living in Rome -- it was typical for the sons of client kings to be brought up at Rome, so they could be hostages to guarantee the king's cooperation and at the same time be imbued with a full and lasting sense of the majesty of Roman power, the superiority of Roman culture. In any case, Claudius decided that Agrippa II was too young to become king in 44; thus Judea reverted to provincial status and was placed back under the administration of procurators. What was the state of the state at the time of the death of Agrippa I? /+/

Jews Under Agrippa I and Agrippa II

Agrippa II

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Not unlike his grandfather, Herod the Great,Agrippa I is a mass of carefully engineered contradictions, in his own person and practices an embodiment of the irresoluble forces which were pulling the Jewish state to pieces. He won Josephus' approval for living among the people in Jerusalem and scrupulously observing the daily rituals. At the same time, he catered to his non-Jewish constituency with lavish secular construction projects outside Jerusalem, baths, stoas, and even an amphitheater. This amphitheater saw one gladiatorial contest in which 1400 "criminals" perished (Josephus, Ant. 19.7.5 [337]). [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

“On the other side, he gratified the Pharisees by assisting in the persecution of Christians, notably James and Peter, though the latter miraculously escaped (Acts, 12. 3-19). This earned him from the Gospel authors the following account of his death: ‘And immediately, because he had not given the glory to God, an angel of the Lord struck him down, and he was eaten by worms and died." ( Acts, 12. 23; compare Jos. Ant. 19.8.2 [344 ff], where the cause of death looks to have been a burst appendix). The point, though, is that to be successful as a political leader in the Palestine of the first century AD required a person to show several different faces; thus the coins of Agrippa minted for use at Jerusalem bore no graven image, while those for use outside the city were graced with his image. /+/

“Agrippa II eventually was given a small kingdom in the north of Palestine, with his capital at Caesarea, and he ruled in his little corner (which was shuffled once or twice) until his death in 93; but despite the length of his rule, he is an insignificant figure, because the major historical events of the time were brewing at Jerusalem, to which city Agrippa II was only an occasional visitor. /+/

“A central question for the history of this period is: what were the causes of the Jewish War? As so often with these questions, more than one answer may be right, but modern accounts tend to emphasize one at the expense of others. In this case the main choices are: (1) the corrupt and bumbling administration of the procurators, who acted without either due regard for the delicate sensibilities of the Jews or awareness of the powder keg of religious tensions among the Pharisees, Sadduccees, Essenes, Zealots, Christians, and Gentiles; (2) the powder keg of religious tensions among the Pharisees, Sadduccees, Essenes, Zealots, Christians, and Gentiles, such that there was nothing the procurators could have been expected to do to prevent the explosion (so esp. Schü rer, author of the monumental 19th century work History of the Jewish People in German [translated and updated by various hands, Edinburgh 1973]; (3) a Marxist approach, not without some justification from the ancient sources, that the Jewish War was really the result of a revolt by the oppressed masses against the Jewish ruling class, whom the Romans (as always) supported.” /+/

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, Live Science, Archaeology magazine, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024