Home | Category: Jews in the Greco-Roman Era

JEWISH WARS

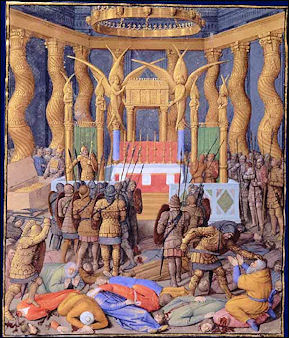

Medieval vision of the sacking

of Herod's Temple

The Jewish Wars — also known as the Jewish–Roman Wars — were a series of large-scale revolts by the Jews of Judaea and the Eastern Mediterranean against the Roman Empire between A.D. 66 and 135. The First Jewish–Roman War (A.D. 66–73) and the Bar Kokhba revolt (B.C. 132–136) were nationalist rebellions, striving to restore an independent Judean state (more or less in present-day Israel) , while the Kitos War (A.D. 115–117 CE) was more of an ethno-religious conflict, mostly fought outside of Judaea, which at the time of the wars was a Roman province. [Source: Wikipedia]

The devastating impact the Jewish Wars had on the Jewish people can not be emphasized enough. At the time the wars began, by some estimates, Jews made up seven percent of the population of the Roman Empire. The wars transformed them from a major population in the Eastern Mediterranean into a dispersed and persecuted minority.

The First Jewish-Roman War climaxed with Roman sacking of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Jewish Temple. Other towns and villages in Judaea were also razed. Maybe tens of thousands died and perhaps hundreds of thousands were uprooted or displaced. Those who remained were stripped of all forms of political autonomy. The brutal put down of the Bar Kokhba revolt a half century later resulted in an even worse massacre. So many Jews were killed Judea experienced a significant population drops. Jews that weren’t killed outright were expelled, or sold into slavery. On top of this Jews were banned from residing in the area of Jerusalem, which the Romans rebuilt into the pagan colony of Aelia Capitolina. The province of Judaea was renamed Syria Palaestina.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FLAVIANS (RULED FROM A.D 69-96): TITUS, DOMITIAN AND THE JEWISH WARS europe.factsanddetails.com

SECOND TEMPLE OF JERUSALEM (HEROD'S TEMPLE) africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIFE OF THE JEWS AROUND THE TIME OF JESUS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

UNREST AND PERSECUTION OF JEWS IN THE A.D. FIRST CENTURY ROMAN EMPIRE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MASADA: HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGY, MASS SUICIDE africame.factsanddetails.com

SIEGE OF JERUSALEM BY THE ROMANS IN A.D. 70 africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; Bible and Biblical History: ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Bible History Online bible-history.com Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Jewish History: ; Complete Works of Josephus at Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org ; Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Jewish War” by Flavius Josephus , Betty Radice, et al. (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“The Antiquities of the Jews” by Flavius Josephus, Allan Corduner, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Masada - The Complete Epic Mini-Series” (DVD) Amazon.com ;

“The Jewish Revolt AD 66–74" by Si Sheppard and Peter Dennis Amazon.com ;

“Jews In The Roman World” by Michael Grant Amazon.com ;

“The Jews among the Greeks and Romans: A Diasporan Sourcebook”

by Professor Margaret Williams Amazon.com ;

“The Herods: Murder, Politics, and the Art of Succession”

by Bruce Chilton, Paul Heitsch, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Herod's Temple: A Useful Guide To The Structure And Ruins Of The Second Temple In Jerusalem” by Michael Lustig Amazon.com ;

“An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel, and Jesus” by Lester L. Grabbe Amazon.com ;

“Between the Testaments: Pharisees, Sadducees and Essenes” by Robert C. Jones Amazon.com ;

“The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English: Seventh Edition”by Geza Vermes (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

“The Story of the Jews” Volume One: Finding the Words 1000 BC-1492 AD by Simon Schama (Author) Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Unrest, Messiahs, and ewish Guerilla Movements

The A.D. first century, when Jesus lived, was a time of social unrest when many Jews were interested in the coming of a Messiah. The unrest can be traced back to the Maccabean revolt in 167 B.C., a nationalist Jewish rebellion against Greek rulers. Many young Jewish men died as martyrs. The Maccabean revolt set off a long period of chaos, social upheaval and expectations of a Messiah. Jews, in Jesus's time, believed that the Messiah was more likely to be a strong military leader than a gentle, moralizing preacher. The prophet Isaiah predicting that the Messiah would be a "Prince of Peace" who conquered the Assyrians "like the mire of the streets," reduced Damascus to "a ruinous heap," transformed Babylon into a city inhabited only by owls, satyrs and other "doleful creatures," and in Egypt “turn everyone against his neighbor, city against city, and kingdom against kingdom."

At the time of Jesus's birth, the Holy Land was crawling with militant Jewish groups engaged in a prolonged guerilla-style warfare against the Roman army. The districts of Palestine, where Jesus lived and worked were major centers of insurgent activity.

Abatur at the scales

an image with Essenes roots? Militants Jewish groups and “bandit-guerrillas” were active in the decades before the birth of Christ and they continued being active decades after his death until a full scale Jewish revolt in A.D. 68 when a leader named Manahem took control of the temple area by driving out the Roman troops and executing the high priests. Six Roman legions were required to put the revolt down. Josephus chronicled five major Jewish military messiahs, not including Jesus or John the Baptist, between 40 B.C. and A.D. 73.

The Romans referred to the Jewish insurgents as bandits even though most of their targets were absentee landlords and tax collectors. They were also sometimes called "zealots" (a reference to their zeal for Jewish law and the promise of God's covenant). Bandit-guerrillas who were caught were often crucified or beheaded in public.

The zealot-bandits practiced guerilla tactics that would have made Mao proud: they seized armories, staged hit and run attacks and assassinations and carried out suicide mission and terrorist attacks on the palaces of important leaders. Many of the fighters lived in caves or mountain hideouts. Some urban guerilla fighter were known as "dagger men," because they carried knives in the folds of their robes.

From time to time these guerilla leaders lead uprisings that were quickly dashed by the Roman military. Herod made a name for himself by ambushing two threatening Jewish leaders. One leader was executed in front of a cave in full view of his wife and seven children. In 4 B.C. Jews angry over the execution of students caught trying to remove a Roman eagle from temple decoration launched a city-wide riot. Eventually some 2,000 Jews were crucified.

A violent protest broke out over the Roman transgression of the Jewish taboo on graven images and the use of temple funds to build an aqueduct to supply the Romans with water for their bathes. During a Passover feast in 50 A.D. a Roman centurion raised his tunic and farted into a group of pilgrims. "The less restrained of the young men and the naturally tumultuous segments of the people rushed into battle," Josephus reported. The Roman infantry was called in and Josephus claimed 30,000 people were trampled to death.

Josephus

Much of what we know about the Jewish Wars comes from Josephus. Titus Flavius Josephus (A.D. 37 – c. 100), also called Joseph ben Matityahu, was a 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian and hagiographer of priestly and royal ancestry who recorded Jewish history, with special emphasis on the 1st century AD and the First Jewish–Roman War, which resulted in the Destruction of Jerusalem and its temple in 70. His most important works were “The Jewish War” (c. A.D. 75) and “Antiquities of the Jews” (c. A.D. 94). “Against Apion” contains the first mention of a five-book Torah. [Source: ccel.org]

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: The main source for both the prelude to the Jewish War and the war itself is Josephus, a Jewish aristocrat who was himself a general of a local Jewish militia. He left behind two works of history: the Jewish War in seven books, a focused account of the years 66-74 AD somewhat on the Thucydidean model, and the Jewish Antiquities, a universal history of the Hebrews in twenty books from the creation to 66 AD. Of these two works, the Jewish War is the earlier, and it begs to be contextualized. [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

“Josephus surrendered to the Romans in 67, whereupon he managed to ingratiate himself with Vespasian by predicting (correctly, as it happened) that Vespasian would become the emperor ( BJ 3.8 [400-402]). He was then attached to the Flavian gens, and after the war he went to Rome, where he wrote the Jewish War under the close supervision of Titus and Vespasian.

“Antiquities of the Jews” by Josephus

Preface to the Antiquities of the Jews

Book I -- From Creation to the Death of Isaac

Book II -- From the Death of Isaac to the Exodus out of Egypt

Book III -- From the Exodus out of Egypt to the Rejection of the Generation

Book IV -- From the Rejection of that Generation to the Death of Moses

Book V -- From the Death of Moses to the Death of Eli

Book VI -- From the Death of Eli to the Death of Saul

Book VII -- From the Death of Saul to the Death of David

Book VIII -- From the Death of David to the Death of Ahab

Book IX -- From the Death of Ahab to the Captivity of the Ten Tribes

Book X -- From the Captivity of the Ten Tribes to the First Year of Cyrus

rendering of Josephus

Book XI -- From the First Year of Cyrus to the Death of Alexander the Great

Book XII -- From the Death of Alexander the Great to the Death of Judas Maccabeus

Book XIII -- From the Death of Judas Maccabeus to the Death of Queen Alexandra

Book XIV -- From the Death of Queen Alexandra to the Death of Antigonus

Book XV -- From the Death of Antigonus to the Finishing of the Temple by Herod

Book XVI -- From the Finishing of the Temple by Herod to the Death of Alexander and Aristobulus

Book XVII -- From the Death of Alexander and Aristobulus to the Banishment of Archelaus

Book XVIII -- From the Banishment of Archelaus to the Departure of the Jews from Babylon

Book XIX -- From the Departure of the Jews from Babylon to FAdus the Roman Procurator

Book XX -- From Fadus the Procurator to Florus

[Source: Complete Works of Josephus at Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL), translated by William Whiston, ccel.org ]

“War of the Jews” by Josephus

Preface to the War of the Jews

Book I -- From the Taking of Jerusalem by Antiochus Epiphanes to the Death of Herod the Great

Book II -- From the Death of Herod till Vespasian was sent to subdue the Jews by Nero

Book III -- From Vespasian's coming to Subdue the Jews to the Taking of Gamala

Book IV -- From the Siege of Gamala to the Coming of Titus to besiege Jerusalem

Book V -- From the Coming of Titus to besiege Jerusalem to the Great Extremity to which the Jews were reduced

Book VI -- From the Great Extremity to which the Jews were reduced to the taking of Jerusalem by Titus

Book VII -- From the Taking of Jerusalem by Titus to the Sedition of the Jews at Cyrene

The Life of Flavius Josephus - Autobiography

Josephus's Discourse to the Greeks concerning Hades

Flavius Josephus Against Apion

Biases in Josephus’s Accounts of the Jewish Wars

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: Clearly the circumstances were not conducive to objectivity. Two major kinds of bias are detectable in this narrative. First, and most obviously, there is a whitewash of the Flavians, who unfailingly prosecute the war with a minimum of acrimony, sparing the Jews wherever possible, and ever ready to give them a chance to surrender. Titus is even made to oppose the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, which in Josephus' account happens as the result of a firebrand flung by a lone legionary in defiance of Titus' orders ( BJ 6.5 [252]); to spare religious sanctuaries was the standard practice of ancient warfare, but in this case the Temple was also a fortress, indeed the main stronghold of the Jewish resistance, and so a legitimate military target. The pro-Flavian bias of the Jewish War may be savored in Josephus' description of Vespasian's elevation by his troops: ‘But the more he declined, the more insistent his officers became, and the soldiers surrounded him, swords in hand, and threatened to kill him if he refused to rule as he was entitled. After earnestly impressing on them his many reasons for rejecting imperial honors, and failing to convince them, he finally yielded to their call.’ ( BJ 4.4 [603-604]; cf. Suetonius Vesp. 6) [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

“But at the time of the writing of the Jewish War, Vespasian was already securely established as emperor, so legitimation of his rule cannot be called the primary motive of the work. The second major area of bias concerns the war guilt of the Jews. For Josephus, the war was in the first instance caused by the corrupt and inept Roman procurators, and secondarily the work of misguided bands of extremists, sicarii (thugs) and zealots who led the people astray; he is concerned to exculpate the Jewish aristocracy. For Josephus, the legitimate representatives of Judaism were the Pharisees, Sadduccees, Essenes and high priests; in his account all of these groups work consistently to prevent the rebellion. We shall see that this is a false picture, but its purpose is clear: Josephus is concerned to discourage further reprisals by the Romans against the Jews, both in Palestine and those of the Diaspora, and to effect a reconciliation in the wake of the bitter struggle. /+/

Josephus’s Insights Into the Jewish Wars

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “That Josephus himself recognized the shortcomings of his Jewish War is evident. Again, in the Thucydidean mold the account of the war is prefaced with a cursory narrative of the preceding years, in this case covering the period 170 BC to 66 AD. In the later revisionist and more comprehensive Jewish Antiquities he chooses to go over much of the same ground again. The Jewish Antiquities was published in 93-94 AD, when the post-war position of the Jews was settled and Josephus himself was relatively free from political pressures; in it modern historians have found the true Josephus, at his best both meticulous and even-handed. [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

Arch of Titus relief of the Roman sacking of Jerusalem

“Let us now consider the evidence for the thesis that maladministration by the Roman procurators caused the Jewish revolt. An event from the administration of the first Claudian procurator, Cuspius Fadus (44-46?), illustrates the tenseness of the situation and the myriad opportunities for misunderstanding and overreaction. Here is Josephus' account of the incident: “Now it came to pass, while Fadus was procurator of Judea, that a certain magician, whose name was Theudas, persuaded a great part of the people to take their effects with them and to follow him to the river Jordan, for he told them that he was a prophet and that by his own command he would divide the river and afford them an easy passage over it; and many were deceived by his words. However, Fadus did not permit them to make any advantage of his wild attempt, but sent a troop of horsemen out against them, who fell on them unexpectedly, slew many of them, and took many others alive. They also took Theudas alive, and cut off his head, and carried it to Jerusalem. ( Ant. 20.5.1 [97]) /+/

“Although Josephus does not say why people were following Theudas or why they wished to cross the Jordan with all of their possessions, the answer may be inferred both from Josephus' account and from a general knowledge of trends in the popular religion of the time. The legacy of the Old Testament prophets had been transmuted into a fervently eschatological mode; like many another Hebrew prophet, including (at least in his earthly corporeal form) Jesus, Theudas must have been predicting that the end of the world was at hand, and that the destruction would fall first upon Jerusalem and its environs. Moreover, his promise to part the waters of the Jordan river is an unmistakable allusion to the parting of the Red Sea by Moses, the liminal event in the escape of the Jews from Egyptian slavery ( Exodus 14. 26-29). This means that the episode of Theudas is more than an example of procuratorial misconduct; many of Theudas' followers must have been actual slaves (making their flight illegal and justifying the intervention of the authorities, from a legal if not from a moral point of view). Others would have been poor but free persons who nevertheless saw themselves as enslaved, either to the Romans or to the landed Jewish aristocracy, or both. In the massacre at the river Jordan, then, we have a confluence of class tension and religious extremism. It is the Jewish War in microcosm. /+/

“The administration of Fadus' successor, Ti. Iulius Alexander (?46-48), was uneventful save for a famine, which was relieved in the usual fashion by the public generosity of a local notable, in this case the Jewish convert Queen Helena of Adiabene. Under the next procurator, Ventidius Cumanus (48-52), there was an unfortunate episode: during the celebration of Passover, while the Jews were gathered in prayer outside the Temple, a Roman soldier mooned the crowd (Ant. 20.5.3 [112]). A riot ensued, in which a large number of Jews (20,000, by Josephus' surely exaggerated reckoning) were trampled to death. This event lends no support to the class warfare theory. Neither does it especially show procuratorial negligence, nor make the case that the Romans simply did not understand the Jewish attitude towards the sacred rituals; Cumanus seems to have tried to calm the situation, and presumably the soldier knew full well that his exhibitionism would be provocative. This same Cumanus proved his understanding of the Jewish attitude towards sacrilege when he ordered the execution of a legionary who had publicly destroyed a scroll of the Torah. If anything, the Passover massacre lends support to the Schü rer thesis: the Jews brought trouble onto themselves by their fanaticism and inflexibility. /+/

“More evidence, perhaps, for the Schü rer line in the downfall of Cumanus. Sometime around 50 AD a group of Galileans making the holiday pilgrimage to Jerusalem got into a scrape with members of the non-Jewish community in Samaria. This developed into a little civil war, in which Cumanus took part on the side of the Samaritans, and the disorder was such that the provincial governor of Syria, C. Ummidius Quadratus, was forced himself to come to Palestine and judge among the parties in conflict. He found the Jews so violently opposed to Cumanus, whom they accused of taking bribes from the Samaritans, that he referred the whole matter to the emperor himself, and sent Cumanus to Rome together with representatives of both sides. Fortunately for the Jews, they had powerful advocates at the court in the persons of King Agrippa II and the younger Agrippina, who together persuaded Claudius to find against the Samaritans; Cumanus was deposed and exiled. What to make of this? Josephus' account of the whole affair is suspicious ( Ant. 20.6), especially in so far as it is never clear what, if the Samaritans did start it by murdering the pilgrims as he claims, their motive is supposed to have been. There is no clear grounds for faulting Cumanus' conduct in the affair; taking Josephus' account with several grains of salt, it looks as if he was simply using force to try to restore order. Oesterley says that Ummidius Quadratus' intervention, whereby he pulled rank on the procurator Cumanus, must have lessened the respect for the authority of the procurator among the masses of the Jews and thereby contributed to the rise of revolutionary spirit; if so, this is a minor factor only, as by all indications the procurators had been getting little enough respect as it was. The episode is important for two reasons: (1) it led to the exchange of a bad procurator for a slightly less bad one, and (2) it illustrates how hard it must have been to try to keep the lid on the boiling pot of Palestine.” /+/

Felix, Festus, Florus and Events Before the Jewish Wars

Antonius Felix

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “The administration of the next procurator, M. Antonius Felix (52-60), was eventful ... and disastrous. It is during his tenure that the Christians begin to appear in the sources as a major contributor to the popular unrest, and it is this same Felix who judged St. Paul guilty (of what, it is not clear) and sent him to prison ( Acts 24). Both Paul and his Jewish prosecutor, Tertullus, address Felix with respect: ‘Your Excellency, because of you we have long enjoyed peace, and reforms have been made for this people because of your foresight. We welcome this in every way and everywhere with utmost gratitude.’ ( Acts 24:2-3) “Even Josephus has something good to say about Felix: “As for the affairs of the Jews, they grew worse and worse continually, for the country was filled with thugs and charlatans, who deluded the multitude. Yet Felix caught and put to death many of those impostors every day, together with the thugs.’ ( Ant. 20.8.5 [160]) [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

“But would not be wise to conclude that Felix was very much better liked than Cumanus had been. Tertullus is flattering the governor in the manner appropriate to the circumstances of his speech, and even the apostle was not incapable of the obligatory rhetorical flattery on occasion (cf. Acts 24:10). Certainly it was part of Felix's job to suppress lawlessness, and Josephus does not hesitate to commend his use of military force against the sicarii. Notice though that in the quoted passage Josephus lumps the thugs together with the false prophets, though the two phenomena were unquestionably separate. In the parallel account of the same events in the Jewish War, the sicarii and the messianic impostors start out as two separate entities, but they are inexorably merged, especially after a large group (30,000 according to Josephus) in the late 50's follows one of these false messiahs (identified by Josephus only as the Egyptian) into the wilderness, where they are attacked by Felix's troops as a revolutionary body and annihilated: ‘The impostors and the brigands, banding together, incited many to revolt, exhorting them to assert their independence. They threatened to kill any who submitted willingly to Roman domination, and to suppress all those who would accept servitude voluntarily.’ ( BJ 2.13.6 [264]) This is reflective of Josephus' agenda, as described above: to exculpate the Pharisees and the Jewish aristocracy, and to account for the religious element of the growing spirit of rebellion (as it could not be denied) by representing it as a perversion of the true Judaism. /+/

“Felix was succeeded in 60 AD by M. Porcius Festus, whose two year administration continued the pattern already established by his predecessor. From Josephus he gets a brief word of praise for continuing to harass the sicarii. But yet another false prophet led his followers into the desert to be slain by Festus' troops (unless this be a doublet of one of the prior episodes -- Ant. 20.8.10 [188]). Festus is remembered primarily for his fair treatment of St. Paul, whom he released from prison in recognition of his right of appeal to the emperor as a Roman citizen ( provocatio ; see Acts 25:6-12). Between the death of Festus in 62, and the arrival of his successor Albinus (62-64), the Sadducee high priest took it upon himself to step up the persecution of the Christians; his best known victim was James, reputedly the brother of Jesus. Other than that, Albinus' tenure left the impression of a truly Verrine rapacity ( BJ 2.14.1 [272-3]). Although he too pursued the sicarii, at times he was willing to play both ends against the middle in the political rivalries of the Jews, so long as there was a profit in the game. On the verge of being replaced, and knowing that he would be tried for extortion, Albinus got his revenge in advance by releasing all of the sicarii he had imprisoned (cf. Ant. 20.9.5, where Josephus represents the act as an attempt to curry favor with the Jews at the last minute and so avoid prosecution). /+/

“Such a man was Albinus, but by comparison his successor Gessius Florus made him appear an angel. The crimes of Albinus were, for the most part, perpetrated secretly and in disguise; Gessius, on the contrary, paraded all the wrongs he did to the nation openly ... ( BJ 2.14.2 [277]). Here the apologetic character of the BJ appears in full relief. The pot is boiling, boiling over, but it must be that Florus himself is stirring it, even for his own selfish purposes. The Jews are complaining about him to the governor of Syria: ‘If the peace lasted, he foresaw that he would have the Jews accuse him before Caesar, but if he contrived to make them revolt, he hoped that this greater outrage would forestall any inquiry into less serious offenses. So, to ensure a nationwide revolt, he added daily to their sufferings. ( BJ 2.14.3 [283]) /+/

“Moreover, Josephus has Florus closely in league with the sicarii. Given what we have already seen, that Josephus is concerned to conflate brigandage and Messianic cults, and that the only time he has anything good to say about a Roman procurator is when action is taken against these enemies, Florus' alleged partnership with the sicarii ought to mean that whereas his predecessors had short-sightedly regarded these mass departures into the wilderness to await the coming of the Messiah as acts of war, Florus saw that that they posed no threat (at least not to Roman authority over the province) and let them go unpunished. From another angle, though, this inaction was in itself short-sighted, since free reign to the Messianic movements was anathema to the religious authorities and the aristocracy, and thus exacerbated the internal tensions. /+/

Beginning of the Jewish Wars

Medieval vision of the

coming of the Jewish Messiah David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “As Josephus sees it, the war began when Florus demanded a payment of 17 talents from the treasury of the Temple, claiming to be collecting back taxes and acting on Nero's orders. The populace blocked his way to the Temple, the troops cut a path to the door. In itself, this riot was no worse than the one occasioned by the untimely display of the legionary buttocks; but it came at a time when the balance of power in the province had been so upset, and the tensions among the various groups were so pronounced, that there was no going back. [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

“The Messianic element of the popular religion played a large role. The ravages and ineptitude of the procurators did not help. Class hatred was also a factor, but to some degree this element is exaggerated by Josephus, who wants to make it clear that the best people among the Jews, those on whom the Romans had always relied, were not guilty. I will not here try to narrate the events of the war, still less attempt to disentangle the shifting factions which composed the rebel armies, but one thing needs to be made clear: the Jewish war was no less a civil war than a war against Roman overlordship. When the Romans paused (as when Vespasian temporarily suspended his own command, as the law required, upon the death of the man who had conferred it on him) the Jews immediately turned to fighting one another. “ /+/

In A.D. 64, Nero blamed the great fire of Rome on the Jews. Shortly afterwards there was a Jewish revolt that lasted from A.D. 66 to 73. Six Roman legions (35,000 men), Rome's most modern weaponry and siegecraft, and the leadership of two future Roman emperors to put down.

Jewish Revolt in A,D 66 and Siege of Jerusalem in A.D. 70

In A.D. 66, there was a Jewish revolt at Herod's Temple in Jerusalem. At that time bandit-guerrillas were at the height of their power and they were everywhere. A leader named Manahem took control of the temple area by driving out the Roman troops and executing the high priests. The same year there was also a major revolt in Caesara that led to the death of 20,000 people, nearly all of the Jews that lived in the city.

Nero dispatched Vespasian and a large Roman force to Judea (Israel) to put down the rebellion. Halfway through the war Nero was overthrown and Vespasian was proclaimed emperor by the Roman army. Nero died in A.D. 68, when the Jewish revolt had escalated. Vespasian didn't last long. He was succeeded by his son Titus.

The first revolt, in 70 CE, led to the destruction of the Temple. This brought to an end the temple worship and is still perceived by traditional Jews as the biggest trauma in Jewish history. It is marked by the fast day of Tisha B'av (meaning the ninth day of the month of Av). A second revolt, in 132 CE, resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands of Jews, the enslaving of thousands of others, and the banning of Jews from Jerusalem

In response to a revolt against their rule, the Romans reclaimed Jerusalem after ruthlessly besieging the city and destroying the city’s Second Temple in A.D. 70. The Roman army under Titus put down the revoltand punished rebellious Jewish zealots by salting agricultural land, slaughtered and enslaved thousands of Jews, and looted menorahs and other sacred objects. Thousands of Jewish slaves were brought to Rome from Judea. During a huge triumphal procession, commemorated by the Arch of Titus, Jewish prisoners were paraded through the streets and strangled at the Forum.

See Separate Article: SIEGE OF JERUSALEM BY THE ROMANS IN A.D. 70 africame.factsanddetails.com

Evidence of Ancient Roman Battle Found in Jerusalem

Archaeologists discovered a field of stones and other projectiles outside an ancient wall in Jerusalem that could be artifacts from the 2,000-year-old war between the Jews and Romans. According to the Live Science: The excavations, which took place in Jerusalem Russian Compound, revealed a thick wall, believed to be the city's "Third Wall," described by the historian Josephus. The ground outside the wall was covered with these large battle stones, which researchers think date back to the Roman siege of Jerusalem in A.D. 70. [Source Megan Gannon, Live Science October 16 and 22, 2016]

Outside the wall, the archaeologists found that the ground was littered with large ballista stones (stones used as projectiles with a type of crossbow) and sling stones, suggesting that this area had been under heavy fire from Roman siege engines. The Romans would have shot these stones with slings or other more sophisticated siege engines like ballista.

Josephus said the wall was built to protect a neighborhood called Beit Zeita, which was built outside the city's boundaries at the time. The construction was started by Agrippa I, King of Judea, and was finished two decades later to help fortify the city as Jewish rebels prepared to revolt against Rome in A.D. 66. Among the other articles that were found were a corroded metal spearhead and broken jars that helped archaeologist date the battlefield back to Roman times.

Bar Kokhba Revolt and Its Aftermath

Caesarea

A second revolt — the Bar Kokhba Revolt in A.D. 132 — resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands of Jews, the enslaving of thousands of others, and the banning of Jews from Jerusalem. During the Bar Kokhba Revolt, the Jews rose up against the Roman Empire. Although the revolt had some initial successes, the Romans' counterattack resulted in mass slaughter. "Five hundred and eighty thousand men were slain in the various raids and battles, and the number of those that perished by famine, disease and fire was past finding out … thus nearly the whole of Judaea was made desolate," Roman historian Cassius Dio wrote in his book "Roman history" (translation by Earnest Cary). There is some debate on the accuracy of the death toll but it seems clear that many died. Numerous caves where refugees hid from the Roman army have been found in the Judean Desert. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, March 8, 2024]

Paul Mendes-Flohr wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: Sixty years after the destruction of the Temple, Simeon Bar Kokhba led the Jews in a revolt against their Roman overlords. When the emperor Hadrian disclosed plans to establish a Roman colony on the ruins of Jerusalem — to be called Aelia Capitolina in honor of himself, Aelius Hadrianus, and the god Jupiter Capitolinus — he provoked a war. Led by Simeon Bar Kokhba, the well-planned revolt, which broke out in 132, took the Romans by surprise. The Jewish rebels first liberated Jerusalem and then seized control of Judea and large parts of Galilee. Enthralled by Bar Kokhba's spectacular victories, many Jews, including Rabbi Akiva, widely regarded as the pre-eminent scholar of his generation, hailed him as the Messiah, and he was named the nasi (prince or president) of Judea. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices,2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

After three years the tenacious and valiant forces of the revolt were put down, and Bar Kokhba himself was killed in the last decisive battle, in the summer of 135. (According to one account, he was taken captive and enslaved.) The historian Cassius Dio wrote that 580,000 Judeans died in battle or from hunger and disease. and almost 1,000 villages were destroyed. In the aftermath the Jews were banished from Jerusalem, and Jewish ritual practices, including circumcision, study of the Torah, and observance of the Sabbath, were prohibited. The spiritual leadership was summarily executed, and most of the remaining Jewish population, including scholars, fled the country. The Romans quickly repopulated Judea with non-Jews, and the Land of Israel, aside from Galilee, ceased to be Jewish.

The fugitives from Judea scattered throughout the Mediterranean. Joined by scholars, these Jews spread to Asia Minor and westward to Spain, Gaul (France), and the Rhine valley, where they organized self-governing communities. Those Jews remaining in the Land of Israel also slowly reorganized themselves. The Sanhedrin (Greek for Council of the Elders), which formerly had its seat in Jerusalem, was reconstituted in Jabneh (Yavneh) as the supreme representative body in religious and communal affairs. The institution continued until the early fifth century, when the Roman authorities abolished the office of the presidency of the Sanhedrin.

In 2013, archaeologist announced they had discovered “a veritable treasure chest” of jewelry and coins buried inside a pit in the courtyard of an ancient building in southern Israel’s Kiryat Gat region. Archaeology magazine reported: According to the Israel Antiquities Authority’s Sa’ar Ganor, the cache likely dates to the time of the Bar Kokhba revolt, which lasted from A.D. 132 to 135, and was one of the largest Jewish uprisings against the Romans. “This was probably an emergency cache that was concealed at a time of impending danger by a wealthy woman who wrapped her jewelry and money in a cloth and hid them deep in the ground,” says Ganor. “It’s now clear that the owner never returned to claim it.” While there are other contemporary hoards from Israel, this example is exceptional for the inclusion of several gold coins, rare in Israel at this time. [Source: Mati Milstein, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2013]

Cave of Horror and Bar Kokhba Coins

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Imagine that you knew that you were going to die. Having taken refuge from a merciless military regime in a cave, you now realize that you are trapped in a prison of your own making. The enemy is camped above you and so you, your family, and your friends face a slow, painful death from starvation. What would you talk about? How would you console your children? How would you pass the days? The situation is horrifying and almost impossible for us to picture, but a new archaeological discovery sheds light on the last days of a small group of freedom fighters in ancient Judea. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, March 20, 2021]

“Fragments of a biblical scroll have been discovered in the uninvitingly named “Cave of Horror” in the Judean desert in Israel. The fragments, which are written in Greek and are almost two millennia old, are the literary legacy of a small band of Jewish rebels who starved to death there in the second century A.D. The discovery is the first time in 60 years that a biblical scroll has been found in an archaeological context, and it gives us insight into the final days of this small group.

The Cave of Horror (sometimes known as the Cave of Skulls) was discovered in 1960. Its name is derived from the 40 skeletons discovered when archaeologists first entered the cave. The human remains belong to members of the Bar Kokhba revolt. A group of refugees from the war — men, women, and children — fled to the desert and hid in caves on what is now the West Bank. The Romans camped above the caves at the top of the cliff and those hiding in the cave below slowly starved to death.

“Though the Cave of Horror was excavated in the 1960s the difficulty accessing the cave — it is 80 meters below the cliff top and archaeologists have to rappel down the cliff to access it — means that it has remained largely inaccessible. Interest in its secrets was sparked by a 2017 Israeli Antiquities Authority initiative to find and retrieve priceless scrolls hidden in the Judean caves before looters have the chance to steal them. The preemptive effort has meant that many previously excavated sites, like the Cave of Horror, are receiving renewed attention.

“Alongside a biblical scroll the team unearthed something macabre: the mummified remains of a small child. Inside the cave, in a shallow pit, they found the remains of a girl who died between the ages of 6 and 12, and had been interred in the fetal position. Her remains are 6,000 years old. Even more stunning was the discovery of a prehistoric woven basket estimated to be 10,500 years old. If the dating is correct this would make the basket the largest intact basket ever discovered.

“The excavation also unearthed a small cache of Bar Kokhba era coins bearing images of a palm tree and vine leaf. The coins, which bore the words “Year 1 for the redemption of Israel,” would have proved useless at the end, but the scrolls may well have served as a source of comfort and consolation to those awaiting their death.

In March 2024, archaeologists announced they found four coins dating to the period of the Bar Kokhba revolt in the Judaean desert of Israel. Live Science reported: The coins were found in the Mazuq Ha-he'teqim Nature Reserve, which is located in the West Bank. They date to the time of the Bar Kokhba revolt (A.D. 132 to 135). [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, March 8, 2024]

One coin has a Hebrew inscription that translates to "Eleazar the Priest," which may refer to Eleazar Hamod'ai, a rabbi who lived in the town of Beitar, the headquarters of the revolt, representatives for the Israel Antiquities Authority said in a statement. Beside Eleazar's name is an engraving of a date palm. On the other side of the coin is another Hebrew inscription, which says, "year one of the redemption of Israel." This indicates that the coin was minted in A.D. 132, during the first year of the revolt, the statement said. There is also an engraving of grapes. The three other newly discovered coins have an inscription saying "Simeon," which may refer to Simeon (also spelled Simon) bar Kokhba, the leader of the revolt, according to the statement.

Dead Sea Scrolls From the Cave of Horror

More than 80 scroll fragments were discovered in the excavation of the Cave of Horror and they were dated (on the basis of handwriting) to the end of the first century B.C.E.Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Like other ancient Greek manuscripts of the Bible, the name of God is preserved in Hebrew. The scroll fragments contain passages from the books of the prophets Zechariah and Nahum, suggesting that the fragments once formed part of a scroll of the 12 minor prophets in the Hebrew Bible. One section contains a poignant passage from Zechariah 8:16-17: “These are the things you are to do: Speak the truth to one another, render true and perfect justice in your gates. And do not contrive evil against one another, and do not love perjury, because all those are things that I hate — declares the Lord.” The fragment from the cave however replaces the word “gates” with “streets.” As Oren Ableman, a member of the IAA team who worked on the scroll fragments, told the Jerusalem Post that he “had never seen this before.” [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, March 20, 2021]

The passage from Zechariah 8:16–17 on the one fragment reads:

These are the things you are to do:

Speak the truth to one another,

render true and perfect justice in your gates.

And do not contrive evil against one another,

and do not love perjury,

because all those are things that I hate — declares the Lord.

Another featured a passage from Nahum 1:5–6:

The mountains quake because of Him,

And the hills melt.

The earth heaves before Him,

The world and all that dwell therein.

Who can stand before His wrath?

Who can resist His fury?

His anger pours out like fire,

and rocks are shattered because of Him.

[Source: Ed Mazza,·,Huffington Post, March 17, 2021]

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons, Schnorr von Carolsfeld Bible in Bildern, 1860 except Jewish sects table, Quora groups

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, Live Science, Archaeology magazine, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024