Home | Category: Late Stone Age and Copper and Bronze Age / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples

CHALCOLITHIC AGE PALESTINE (4,500 to 3,300 B.C.)

The Chalcolithic Age (chalcos, copper; lithos, stone) extended from the middle of the fifth to near the end of the fourth millennium B.C. It is called Chalcolithic because people were were using stone as well as copper depending on the application. Gerald Larue wrote: “ During this period the art of smelting and molding copper was developed, and stone and bone tools were now augmented by a limited supply of implements made of this new substance. The skill developed by smiths in the handling of copper is amply illustrated in the several hundred beautifully fashioned cultic items from the end of the Chalcolithic period that were discovered in a cave near the Dead Sea in the spring of 1961. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“Villages and towns of varying size were now spread throughout Palestine and permanent houses were built of stone, mud-brick and wood, although cave living was still common, and near Beer-sheba there was a whole village with underground living and storage quarters. A rich variety of stone, pottery and copper artifacts, fine flint work, paintings and carvings mark cultural growth in this period. New burial patterns were developed. Often the dead were interred in large storage jars, and at other times bodies were cremated and the remains placed in specially made pottery urns and interred in caves.

Exposed rocks in western Jordan, in the Wadi Faynan region, contain bluish copper ore that can easily be removed my hand. Around 4500 B.C. people discovered that the copper ore, when heated to temperatures yields a metal strong enough to make tools as well as religious objects and other items. The copper found in Wadi Faynan was moved along ancient trading routes from Jordan to Israel, mostly likely on foot and by donkey, to places like the Basheba Valley, where fertile alluvial soils along stream beds supported increasingly large populations. [Source: Katherine Oziment, National Geographic, April 1999]

A Copper Age village, with more than a thousand people and dated to 4200 B.C., was found in Shiquim in the Besheeba Valley in Israel in the 1970s. The people lived in mud brick and stone houses and built an extensive network of underground rooms used to store grain. Large structures used for religious, economic and social purposes were built.

According to Archaeology magazine: The earliest known evidence of domestication of a fruit tree was uncovered at the Chalcolithic site of Tel Tsaf in the Jordan Valley in Israel . During excavations, archaeologists unearthed the 7,000-year-old charred remains of wood, which they determined belonged to olive trees. Although prevalent throughout the Mediterranean world, olives are not endemic to the Jordan Valley. Experts believe that olive trees were imported to the site and cultivated there, allowing its inhabitants to become wealthy by trading in the trees’ valuable products. [Source: Archaeology magazine, September 2022]

See Separate Article: COPPER (CHALCOLITHIC) AGE (4,500 to 3,300 B.C.) factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Bible and Biblical History: ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Bible History Online bible-history.com Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Jewish History Websites: Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Journey to the Copper Age: Archaeology in the Holy Land” by Thomas E. Levy and Kenneth L. Garrett (2007) Amazon.com;

“Masters of Fire: Copper Age Art from Israel” by Michael Sebbane, Osnat Misch-Brandl, et al. (2014) Amazon.com;

The Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Ages in the Near East and Anatolia

by James Mellaart (1966) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Cyprus: From Earliest Prehistory through the Bronze Age” by A. Bernard Knapp (2013) Amazon.com;

“Cyprus Before the Bronze Age: Art of the Chalcolithic Period” by Vassos Karageorghis and Edgar J. Peltenburg (1990) Amazon.com;

“Early Cyprus: Crossroads of the Mediterranean” by Vassos Karageorghis Amazon.com;

“Where God Came Down” by Joel P. Kramer Amazon.com ;

“Archaeology of the Bible: The Greatest Discoveries From Genesis to the Roman Era”

by Jean-Pierre Isbouts Amazon.com ;

“Unearthing the Bible: 101 Archaeological Discoveries That Bring the Bible to Life” Amazon.com ;

“Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology: A Book by Book Guide to Archaeological Discoveries Related to the Bible” by J. Randall Price and H. Wayne House Amazon.com ;

“NIV, Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible (Context Changes Everything) by Zondervan, Craig S. Keener Amazon.com ;

“Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times” by Donald Redford Amazon.com ;

Copper Age in Jordan

Wael Abu Azizeh wrote: It is in the Jordan Valley that the earliest Chalcolithic sites of Jordan were discovered and studied. In Tulaylat al-Ghassul, eight digs carried out from 1929 to 1938 by the Pontifical Biblical Institute, revealed traces of a culture yet unknown, whose origins stem from the Neolithic period. Since these initial discoveries, a high concentration of sites attributed to this period have been identified; along the Jordan Valley (Abu Hamid, Tabaqat Fahl (Pella) and North Tell al-Shuna), and on the highlands of the plateau (Sahab, Qattar, Abu Snesla and Iraq al-Amir). [Source: Wael Abu Azizeh, “Atlas of Jordan”, p. 114-116 Open Edition Books, 2014]

The location of sites is always closely linked to the hydrographic network of wadis that allowed the development of flooded agriculture. In villages, the houses of nuclear families were built using sun-dried bricks, with plastered walls sometimes decorated with remarkable geometric, zoomorphic or anthropomorphic polychrome paintings. Most of the domestic activities of food preparation and craftwork took place in courtyards attached to houses, where the ovens and storage facilities could be found. Large grain silos, like those found at Abu Hamid, reflect the specialization of livelihoods of these people and testify to the emergence of a centralized redistribution of agricultural products. Along with the continued use of carved stone, copper appeared. Although its use is very limited and rare in the domestic context, in Faynan in particular, significant copper mines and work sites are associated with ore deposits.

In the desert peripheries of Jordan, a recent research has revealed a very different situation. Exploration eastwards in the black basalt desert and in the region of the Azraq oasis, and to the south in the Hisma Basin have revealed the existence of a considerable number of nomadic shepherd camps, on the margins of farming villages in the Jordan Valley and Transjordan plateau (Hibr, Azraq, Quweisa and Jabal al-Jill). Surveys carried out with the support of Ifpo in an unexplored area in Al-Thulaythuwat, near the Saudi border, brought new proof of this Chalcolithic desert culture. The habitat of these semi-nomadic shepherds is represented by circular stone enclosures, with rooms which were once covered with a structure made of light materials: courtyards, storage areas and homes (plate II.9 and II.10, fig. II.13). Livestock pens associated with these camps show the particularity of the livelihood of these people, closer to that of semi-nomadic shepherds from the northern Negev in Palestine or from the north-west of the Hijaz in the south.

Objects from Middle East Copper Age Settlements

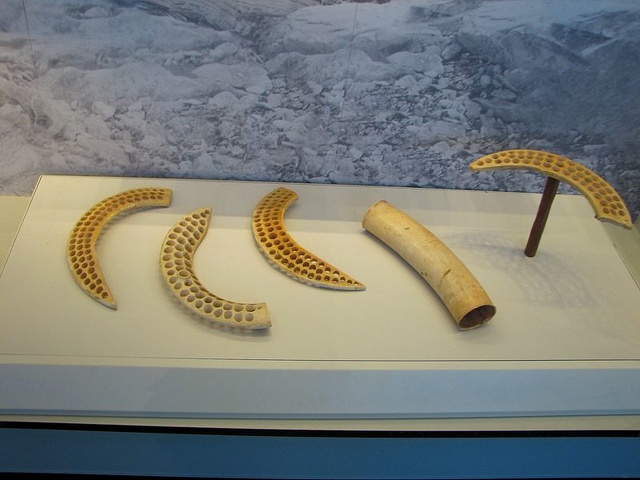

In Copper Age Middle East Period people living primarily in what is now southern Israel fashioned awls, axes, adzes, chisels, vessels, mace heads, ornate standards, crowns and eight-inch rings (probably used as ingots because they were easy to transport and store). In a canyon called Nahal Mishmar on west side of the Dead Sea, archaeologists found 429 objects, dated to 3500 B.C., in reed mats that showed incredible artistry and technical skill.

People from the Chalcolithic Period also made objects from ivory and stone such as figures with large noses and breasts carved from hippopotamus and elephant tusk, violin-shaped figures made of schist, granite and limestone that may have been goddesses from a fertility cult.

In 1993, archaeologists found a skeleton of a Copper Age warrior in a cave near Jericho. The skeleton was found in a reed mat and linen ocher-died shroud (probably woven by several people with a ground loom) along with a wooden bowl, leather sandals, a long flint blade, a walking stick and a bow with tips shaped like a ram's horns. The warrior's leg bone showed a healed fracture.

According to Archaeology magazine: A copper alloy awl found at the Middle Chalcolithic site of Tel Tsaf in the Jordan Valley is the oldest known metal object in the Middle East. It dates to between 5100 and 4600 B.C., perhaps a millennium before native copper metallurgy emerged in the region. The composition of the tool suggests that it was imported from the north, which may have been the source for metallurgical technology that would later emerge. It was found in the most elaborate burial of the period in the region, suggesting it was a particularly rare and coveted item. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2014]

6,500-Year-Old Copper Smelting Forge Found Near Beersheba — the World's Oldest Furnace?

In October 2020 in the Journal of Archaeological Science, Israeli scientists announced they had found the oldest known furnace found — a nearly 6,500-year-old forge used to smelt copper — in the desert around Beersheba. The furnace was found 100 kilometers (63 miles from the mine), indicating the importance of the technology and the lengths Copper Age people went through to keep its location secret. [Source:Caroline Delbert, Popular Mechanics, October 13, 2020]

“The excavation revealed evidence for domestic production from the Chalcolithic period, about 6,500 years ago,” dig director Talia Abulafia said in a statement. “The surprising finds include a small workshop for smelting copper with shards of a furnace — a small installation made of tin in which copper ore was smelted — as well as a lot of copper slag." “Tossing lumps of ore into a fire will get you nowhere,” researcher Erez Ben-Yosef said in the statement. “You need certain knowledge for building special furnaces that can reach very high temperatures while maintaining low levels of oxygen."

“It’s those extraordinary temperatures, still a part of metallurgy today even on the massive global scale, that leads the way to traces you can still see after 6,500 years. “Multiple fragments of furnaces, crucibles and slag were excavated, and found to represent an extensive copper smelting workshop located within a distinct quarter of a settlement,” the paper explains. “Typological and chemical analyses revealed a two-stage technology (furnace-based primary smelting followed by melting/refining in crucibles), and lead isotope analysis indicated that the ore originated exclusively from Wadi Faynan.”

Caroline Delbert wrote in Popular Mechanics The researchers found the workshop evidence more than 100 kilometers (60 miles) from Wadi Faynan, the suspected location of the mine, which is puzzling at first. Then they realized the likely explanation was that copper smelters were worried about intellectual property theft during a time when they had at least a local monopoly on production of valuable copper. This led the researchers to append the idea that the furnace represented another milestone: the beginning of protective “startup”-like innovation culture. “It’s important to understand that the refining of copper was the high tech of that period. There was no technology more sophisticated than that in the whole of the ancient world,” Ben-Yosef said in the statement.

“That contributed to the Ghassulian culture, a group that thrived locally and reached huge artistic achievements. The statement explains: “This culture, which spanned the region from the Beer Sheva Valley to present-day southern Lebanon, was unusual for its artistic achievements and ritual objects, as evidenced by the wondrous copper objects discovered at Nahal Mishmar and now on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.”

Nahal Mishmar Treasure

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In 1961, a spectacular collection of objects dating from the Chalcolithic period (ca. 4000–3300 B.C.) was excavated in a cave in the Judaean Desert near the Dead Sea. Hidden in a natural crevice and wrapped in a straw mat, the hoard contained 442 different objects: 429 of copper, six of hematite, one of stone, five of hippopotamus ivory, and one of elephant ivory. Many of the copper objects in the hoard were made using the lost-wax process, the earliest known use of this complex technique. For tools, nearly pure copper of the kind found at the mines at Timna in the Sinai Peninsula was used. However, the more elaborate objects were made with a copper containing a high percentage of arsenic (4–12 percent), which is harder than pure copper and more easily cast. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org, October 2004 \^/]

“Carbon-14 dating of the reed mat in which the objects were wrapped suggests that it dates to at least 3500 B.C. It was in this period that the use of copper became widespread throughout the Levant, attesting to considerable technological developments that parallel major social advances in the region. Farmers in Israel and Jordan began to cultivate olives and dates, and herders began to use milk products from domesticated animals. Specialized artisans, sponsored by an emerging elite, produced exquisite wall paintings, terracotta figurines and ossuaries, finely carved ivories, and basalt bowls and sculpture.”

“The objects in the Nahal Mishmar hoard appear to have been hurriedly collected. It has been suggested that the hoard was the sacred treasure belonging to a shrine at Ein Gedi, some twelve kilometers away. Set in an isolated region overlooking the Dead Sea, the Ein Gedi shrine consists of a large mudbrick walled enclosure with a gatehouse. Across from the gatehouse is the main structure, a long narrow room entered through a doorway in the long wall. In the center of the room and on either side of the doorway are long narrow benches. Opposite the door is a semicircular structure on which a round stone pedestal stood, perhaps to support a sacred object. The contents of the shrine were hidden in the cave at Nahal Mishmar, perhaps during a time of emergency. The nature and purpose of the hoard remains a mystery, although the objects may have functioned in public ceremonies.” \^/

World’s Oldest Crown: Used for Funeral Rituals Near the Dead Sea

A crown dating to about 3,500 B.C. discovered in the Cave of Treasures near the Dead Sea was used for burial ceremonies during the Copper Age. The Epoch Times and Times of Israel reported: “The Nahal Mishmar Hoard is a collection of copper, bronze, ivory and stone artifacts found wrapped in a reed mat in a cave by the Dead Sea. [Source: Epoch Times and Times of Israel, June 9, 2015]

“A team searching for Dead Sea scrolls in 1961 discovered the treasure hidden in a crevice, behind a boulder deep within the cave. Carbon-dating of the mat places it in the Copper Age between 4,000-3,500 B.C. The amazing find included mace heads, scepters, tools and weapons, many of which were unlike anything ever found.

“One object of particular interest is a crown, believed to be the oldest in the world. It is a thick copper ring with doors and vultures protruding from the top. Based on the symbolism, researchers believe it was used for funeral rituals. The crown was unveiled by New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World as part of the “Masters of Fire: Copper Age Art from Israel” exhibit in 2015.

Rujm El-Hiri

Rujm El-Hiri is a megalith circle in present-day Israel that possibly dates to the Copper Age. S.E. Batt wrote for Listverse:: Also known as the “Wheel of Giants,” Rujm el-Hiri is a large, circular, megalithic structure near the Sea of Galilee. It appears as a giant stone wheel with inner rings and “spokes” that connect everything. Right in the middle of the ring, almost like a bull’s-eye, is a place for burial. [Source: S.E. Batt, Listverse July 1, 2016 ^^^]

“Not only are archaeologists unsure that the burial site was made at the same time as the wheel but further investigation of the site revealed that no burials actually took place in it. It’s thought that valuable artifacts were once here because there is proof that looters hit the site, including a Chalcolithic pin potentially dropped by a looter. ^^^

“As for proposed functions, archaeologists don’t believe it was a place built for dwelling or defense. Some believe that it was a calendar given how the sunrise on the solstices align with the entrances of the wheel. One popular explanation points to the burial site, claiming that people were placed there to undergo excarnation, the act of removing the flesh from a human body. The bones would be moved to another site, which explains the lack of evidence that a burial took place. However, it would be hard, if not impossible, to prove that this actually occurred at Rujm el-Hiri. Regardless, the site has been estimated to have taken 25,000 working days in total to build. Whatever purpose it was meant to perform, it was obviously very important.” ^^^

“Shark Hook” Used off Israel's Coast 6,000 Years Ago

In March 2023, researchers announced they had an unearthed a large copper "shark hook" at a newly discovered village buried under a known archaeological site in Israel. Live Science reported: Archaeologists unearthed the "shark hook" during a 2018 survey along the Mediterranean coast on the outskirts of Ashkelon, a city that was built on top of an ancient seaport of the same name and dates back as far as ancient Egypt. New excavations revealed parts of a village that date back around 6,000 years to the Chalcolithic period, also known as the "Copper Age," which lasted between 4500 B.C. and 3500 B.C. in the region. [Source: Harry Baker, Live Science, March 31, 2023]

The hook is around 2.5 inches (6.5 centimeters) long and 1.6 inches (4 cm) wide, which is big enough to reel in sharks between 6.5 and 10 feet (2 and 3 meters) long, such as dusky sharks (Carcharhinus obscurus) and sandbar sharks (Carcharhinus plumbeus), or large fish such as tuna, all of which are local to the Mediterranean. However, given what marine biologists know about the deep-sea ecosystems in the region, sharks were a more likely target, according to The Times of Israel.

6,000-year-old "shark" hook?

The discovery is a "unique find" because most other fishing hooks uncovered from this time period are smaller and made from bone, Yael Abadi-Reiss, an archaeologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority who co-led the excavation, said in a statement. It's possible that this is one of the first metal variants that people created in the region, considering copper was a relatively new material at the time, she added. "The rare fishhook tells the story of the village fishermen who sailed out to sea in their boats and cast the newly invented copper fishhook into the water, hoping to add coastal sharks to the menu," Abadi-Reiss said.

The village, which is not yet fully excavated, was large for its time period. As such, the residents likely had enough resources to have individuals who were dedicated to metalwork and fishing, Abadi-Reiss said. However, other finds at the site, such as domesticated animal remains, suggest that the village's main source of income and food would have been traditional agriculture.

Not everyone agreed with the findings. One scientist said: This is not a shark hook. It is not even a fish hook. Copper/alloys are too soft and would bend easily under the weight of a fish. There is no attachment groove or eye to hold a line — it would simply fall off as soon as a fish fought back. There is no barb.

Chalcolithic Age Mesopotamia

Gerald A. Larue wrote: “In Mesopotamia, at Tell Halaf on the Khabour River, a tributary of the Euphrates, hard, thin pottery with a beautiful finish produced by high firing at controlled heats was found. This pottery from the middle of the fifth millennium is decorated with geometric designs in red and black on- a buff slip, but animal and human figures also appear. One figure appears to represent a chariot, thus indicating the use of the wheel. Houses were constructed out of mud brick, but reed structures plastered with mud were also built. Cones of clay, painted red or black or left plain, were often inserted in the mud walls to form mosaics and to protect the wall from weathering. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

Ubaid period (6500-3800 BC) frieze of Anzu grasping deer from tell Al-Ubaid

“A small shrine of mud brick from Eridu belongs to the same period. Only foundations and a plastered floor remain, but it is surmised that the upper structure was plastered and painted. Later in the period the shrine was covered over with earth, and a second temple was built above it, placing the new building considerably above the surrounding plateau.

“A more pretentious structure from the beginning of the fourth millennium was found at Tepe Gawra, near modern Mosul. Three large buildings of sun-baked brick were located on an acropolis and designed to frame three sides of an open court. Inner rooms were painted in red-purple, and exterior walls were red on one building, white on another and brown on the third. A fourth millennium temple was built at Uruk upon a staged, elevated mound, 140 by 150 feet at the base and 30 feet high. This man-made, mountain-top home for the gods was of pounded clay and layers of sun-dried brick and asphalt. Surmounted by a white-washed temple (65 x 150 x 14 feet) and approached by a steep stairway and a ramp, this structure is known as a ziggurat (from the Assyrian-Babylonian ziqquratu, meaning "to be raised up," hence "a high place") and is the prototype of loftier and more magnificent ziggurats of later periods.

“For the first time the cylinder seal is found. Each of these small stone cylinders had distinctive patterns inscribed on its surface, and when rolled over soft, moist clay left a raised design, which could be used as a sign of ownership. About the middle of the fourth millennium, pictographic writing was developed and incised upon clay tablets. As the use of writing increased pictographs became more and more stylized, finally being reduced to wedge-shaped symbols or what is called cuneiform writing. Cuneiform characters were impressed upon a tablet of moist clay with a stylus, and if the document required a signature, a cylinder seal was used. The tablet was baked or allowed to dry, forming a permanent record.

“A hearth or incense burner found in one of the caves near Beer-sheba was set in the center of the mud floor and consisted of an arrangement of large pebbles in the form of what has been called "a magic square." Each stone bears a mark in indelible red color, and it is possible that the hearth was used in divination by a priest-magician in the Chalcolithic age. The excavators lifted out the entire section of the floor that contained the hearth and mounted it in a special frame for study and display.

“The precise identity of these Mesopotamian people is not known for sure, but on the basis of the sexegesimal arithmetical system utilized on some of the clay tablets, a system also used by the Sumerians, and from references to gods worshiped by the Sumerians, it is presumed that they were Sumerians. Where they came from and when is unknown,5 but they are neither Semites nor Indo-Europeans, and they refer to themselves as "the black-headed-people."

Chalcolithic Age Egypt

“In Egypt the Chalcolithic period is represented by Badarian culture, first found at al Badari. Unusual, ripple patterned pottery was produced in a variety of finishes. Green malachite ore, so important for the beautification of the eyes, was ground on slate palettes that were often ornamented. Skeletal remains indicate that the Badarians were a stocky people and that they believed in some form of afterlife, for the dead were buried in a flexed or sleeping posture with food and equipment. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

In burial urns from the plain of Sharon the deceased person was cremated and the ashes and bones were placed in these clay house-shaped ossuaries. Each urn is individualistic in design and structure, which may indicate stylistic variations in the architecture of the dwellings of the period. The significance of the "nose-like" projection is not known.

Badari period string of beads

“The succeeding culture, beginning with the fourth millennium, was called Amratian, after el-Amreh near Abydos, and was centered in Upper Egypt. A new people, tall and slender, appear. Some features of their artifacts demonstrate borrowing from the Badarians, but the extensive use of copper, magnificent flint work, and artistic expressions in slate, ivory and clay mark unique developments. Amratian dead were buried in oval pits in tightly flexed positions. In addition to the usual grave furnishings, ivory and clay figurines of women and slaves were included, leading to the hypothesis that these were miniature substitutions for an older practice of sacrificing living individuals to serve an important individual in the afterlife.

“The Gerzean period began in the middle of the fourth millennium, and for the first time written documents appear in Egypt. Local towns or districts (later called "nomes" by the Greeks) were formed, each with a local symbol that was often mounted on ships to designate district of origin. By conquest, units were joined into larger districts. Gerzian tombs were elaborate: the poor were buried in oblong graves with a ]edge at one side to hold funerary offerings, the rich in tombs lined with mud brick. Gold is found for the first time along with silver and meteoritic iron. Figures on a clay vessel about 113/4 inches high from the late Gerzian period are in deep red against a cream colored background. The wavy handles on each side are known as "ledge handles" and are characteristic of vessels of the same period found in Palestine.

“Within the next half millennium significant administrative changes occurred. Gerzean districts of Upper Egypt united under a single ruler who wore a tall white helmet as a crown. Delta nomes united tinder a king who wore a crown of red wicker-work. By 2900 B.C. the two areas had become one, and the single ruler wore both red and white crowns and was known as "King of Upper and Lower Egypt."

See Metal Tools in Ancient Egypt and Copper Tools in Ancient Egypt Under TOOLS, POSSESSIONS AND EVERYDAY ITEMS IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com

Cyprus—Island of Copper

Covering 3,570 square miles, Cyprus is situated in the northeastern corner of the Mediterranean Sea, south or present-day Turkey and west of present-day Syria. It is the third largest island in the region after Sicily and Sardinia.

Colette and Seán Hemingway of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Cyprus was famous in antiquity for its copper resources. In fact the very word copper is derived from the Greek name for the island, Kupros. Cypriots first worked copper in the fourth millennium B.C., fashioning tools from native deposits of pure copper, which at that time could still be found in places on the surface of the earth. The discovery of rich copper-bearing ores on the north slope of the Troodos Mountains led to the mining of Cyprus' rich mineral resources in the Bronze Age at sites such as Ambelikou-Aletri. Tin, which is mixed together with copper to make bronze, typically at a ratio of 1:10, had to be imported. [Source: Colette Hemingway and Seán Hemingway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“True tin bronzes appear to have been made on Cyprus as early as the beginning of the second millennium B.C. In the nineteenth century B.C., the island is mentioned for the first time in Near Eastern records as a copper-producing country, under the name "Alasia," and it continued to be an important source of copper for the Near East and Egypt throughout most of the second millennium B.C. Scholars, however, are in disagreement as to the exact meaning of "Alasia": whether it refers to a specific site on Cyprus, such Enkomi or Alassa, or to the island itself, or, less probably, to another geographic location. \^/

“Cypriot copper and bronze working was relatively modest in the Early and Middle Bronze Ages, and metalsmiths manufactured a limited range of types, including tools, weapons, and personal objects such as pins and razors. Excavations have revealed increasing metallurgical activity at settlement sites in the Late Bronze Age. Nearly all of the major centers, including Enkomi, Kition, Hala Sultan Tekke, Palaeopaphos, and Maroni, provide evidence of copper smelting, as do smaller settlements, including Alassa and Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios. \^/

See Separate Article: CYPRUS — ANCIENT ISLAND OF COPPER europe.factsanddetails.com

Slave Hill, Biblical-Era Copper Mine: Solomon’s Mine?

Since 2012, Ben-Yosef Erez Ben-Yosef, an archaeologist from Tel Aviv University, has been overseeing an archaeological expedition in the heart of Israel’s Timna Valley, the second biggest source of copper in the southern Levant region. (The biggest is Faynan, farther north in Jordan.) Megan Gannon wrote in Live Science: “People have taken advantage of the copper deposits at Timna for millennia. There are dozens of smelting sites and thousands of primitive mining pits clearly visible in the region today. And the area is still used for copper production; the Mexican mining giant AHMSA has a stake in the region. [Source: Megan Gannon, Live Science, November 25, 2014 |~|]

“Recently, the Timna Valley team has taken a crack at Slaves’ Hill, a smelting factory on top of a mesa that was in operation during the 10th century B.C., the biblical era of King Solomon. Today, there are traces of ancient furnaces at the site and lots of slag, which is the rocky material that’s left over after metal is extracted from its ore. (Essentially, it’s manmade lava.). Nelson Glueck explored the region in the 1930s, he named this hilltop site Slaves’ Hill, assuming that its fortification walls were intended to keep enslaved laborers from running off into the desert. When he saw this very harsh environment, he assumed that the labor force had to be slaves,” Ben-Yosef told Live Science. |~|

“The site has a complicated scholarly history. When Glueck first explored the region, he thought he was looking at Iron Age mines that fueled King Solomon’s fabled wealth. Later research then cast doubt on Glueck’s interpretation. In 1969, an Egyptian temple dedicated to the goddess Hathor was discovered in Timna Valley. Archaeologists at the time took this as evidence that mining in the area was controlled by Egypt’s New Kingdom during the Bronze Age, a few centuries earlier than the supposed reign of King Solomon. |~| “When Ben-Yosef’s team revisited the site, they took carbon dates at Slaves’ Hill, and found that most artifacts date to the 10th century B.C., when the Bible says King Solomon ruled. Still, there is no evidence linking Solomon or his kingdom to the mines (and little evidence outside of the Bible for Solomon as a historical figure). One theory is that the mines were controlled by the Edomites, a semi-nomadic tribal confederacy that battled constantly with Israel. |~|

See Separate Article: KING SOLOMON'S MINES: POPULAR FICTION AND ARCHAEOLOGY: africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, except Hook from Live Science and Beersheba furnac from Israeli Antiquities Authority

Text Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, Department of Religious Studies, University of Pennsylvania; James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html; “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024