Home | Category: Rabbis, Synagogues and Prayers / Jewish Holidays / Jewish Holidays

JEWISH FUNERAL CUSTOMS

Traditional Jewish death rites are simple. At the grave site, a kaddish is said; on various occasions from then on it will be repeated by close relatives to memorialize the deceased. A seven-day full mourning period ( shivah ) follows. (Lesser mourning lasts thirty days, a full year for one's parents.) The anniversary of the death ( yahrzeit ) is celebrated by close relatives. The soul (nefesh) of the deceased is thought to return to God. One rabbi told National Geographic, “We believe that the soul never dies. There remains an accessibility, not just in memories, but in fact.”

Traditional Jewish death rites are simple. At the grave site, a kaddish is said; on various occasions from then on it will be repeated by close relatives to memorialize the deceased. A seven-day full mourning period ( shivah ) follows. (Lesser mourning lasts thirty days, a full year for one's parents.) The anniversary of the death ( yahrzeit ) is celebrated by close relatives. The soul (nefesh) of the deceased is thought to return to God. One rabbi told National Geographic, “We believe that the soul never dies. There remains an accessibility, not just in memories, but in fact.”

According to the BBC: “Liberal Jews permit a choice of cremation or burial, counter to the Orthodox prohibition of the former. Men and women have equal rights to play a part in funeral and mourning rituals. Liberal Judaism encourages organ donation where appropriate and does not insist on the customary speedy Jewish funeral if such a procedure is undertaken. [Source: BBC, August 12, 2009 |::|]

According to Jewish custom, the bodies of the deceased are buried after death as soon as possible, preferably on the same day they die if possible. Because Jews believe that human beings are created in the image of God great care is taken with a body even when it is dead. The body is buried intact. If a person has died violently, all blood, organs and tissue are collected and placed with the body. Cremation is prohibited. Autopsies are allowed only in special cases. The deceased are not embalmed.

A corpse is regarded as extremely polluting. Simply touching the ground near a dead body can make a person impure. In the old days there were elaborate rituals to purify people who had any kind of contact with a dead body. See the Red Heifer.

Mourners ask for forgiveness for anything bad they have done to the deceased during their lives. Close relatives are expected to be deeply distressed and expected to stop eating meat, shaving, drinking alcohol, doing business and attending any kind of party or festivity.

See Separate Article: JEWISH IDEAS ABOUT DEATH, AFTERLIFE AND THE SOUL africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Encyclopædia Britannica, britannica.com/topic/Judaism; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Aish.com aish.com ; Jewish Museum London jewishmuseum.org.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning” by Maurice Lamm Amazon.com ;

“The funeral and cemetery handbook” [Shaʹare neḥamah] by D Weinberger Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Choosing a Jewish Life, Revised and Updated: A Handbook for People Converting to Judaism and for Their Family and Friends” by Anita Diamant, Barrie Kreinik, et al. Amazon.com ;

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Guide for the Perplexed” by Moses Maimonides, Andrea Giordani, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com ;

“Judaism: History, Belief and Practice” by Dan Cohn-Sherbok Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Ancient Jewish Funeral Customs

At the time of Jesus, Jewish families built tombs in the hills throughout Judea and stored human remains in caves in ossuaries (boxes with bones). A newly deceased body world be laid on a rock shelf in the cave. When that body decomposed, family members would stack the bones inside the ossuaries and place the box into a niche. Over the years the caves became crowded with bones and boxes and to conserve space families often places the bones of several individuals into one box.

Describing Herod’s funeral several years after it happened Josephus Flavius wrote in the A.D. 1st century: “The bier was of solid gold, studded with precious stones and had a covering of purple, embroidered with various colors; on this lay the body enveloped in purple robe, a diadem encircling the head and surmounted by a crown of gold , the scepter beside the right hand.”

Moment of Death and Preparation of the Body

Certain actions are taken when it sensed that death is approaching. After death, the body is washed in a carefully ordered sequence, beginning with head, First it is ritually doused in a vertical position, then covered in special burial clothes and a white shroud prepared by “pious women.” Finally it is placed in a plain wooden coffin with no ornaments. During all this straw is thrown on the floor and prayers are read from a special book called the “maaver yabok” . The burial clothes should not have any pockets (the dead don’t carry anything with them) and should not have knots (which may hold the deceased back on their journey). Some broken pottery is placed in the casket to symbolize the destruction of the Temple. These duties are usually performed by a special “holy society” of local Jews, who are specially trained for such tasks and feel honored to spare close relatives the pain of dealing with the corpse. They usually begin their work in private about a half hour after the death and carefully wash their hands three times before each task.

Certain actions are taken when it sensed that death is approaching. After death, the body is washed in a carefully ordered sequence, beginning with head, First it is ritually doused in a vertical position, then covered in special burial clothes and a white shroud prepared by “pious women.” Finally it is placed in a plain wooden coffin with no ornaments. During all this straw is thrown on the floor and prayers are read from a special book called the “maaver yabok” . The burial clothes should not have any pockets (the dead don’t carry anything with them) and should not have knots (which may hold the deceased back on their journey). Some broken pottery is placed in the casket to symbolize the destruction of the Temple. These duties are usually performed by a special “holy society” of local Jews, who are specially trained for such tasks and feel honored to spare close relatives the pain of dealing with the corpse. They usually begin their work in private about a half hour after the death and carefully wash their hands three times before each task.

J.M Oesterreicher wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: As his hour of death approaches, a Jew steeped in the ways of his forefathers admits shame for his sins and asks forgiveness. He begs that his pain as well as his death atone for them, that he be granted the abounding happiness stored up for the just, and that he be admitted to God's presence, where there is fullness of joy. He may appeal to the Lord to take back the soul He lent him in mercy and peace, so that the Angel of Death cannot torment him: "Hide me in the shadow of your wings." He then blesses his children. When the end is truly near, those gathered around him proclaim: "The Lord reigns, the Lord has reigned, the Lord shall reign forever and forever." It is considered a sign of divine favor if a man can die with the profession of faith on his lips: "Hear O Israel! The Lord our God, the Lord is one!" [Source: J.M Oesterreicher, New Catholic Encyclopedia, 1960s, Encyclopedia.com]

Several hours after death, the body is washed in a prescribed way and dressed in a white shroud. For a man it is the same garment he wore for the first time as bridegroom, and later at every New Year's service, on the Day of Atonement, and at the Passover meal. A prayer shawl is wound around his body. All shrouds and coffins have the same simplicity for the rich as for the poor. The moment the coffin is lowered into the grave these words are said: "May he come to his place in peace." If a son buries one of his parents, he prays thus:

May His great name be magnified and sanctified in the world that is to be created anew, where He will quicken the dead and raise them up to life eternal, where He will rebuild the city of Jerusalem and establish His Temple in its midst, and where He will uproot all alien worship from the earth and restore the worship of the true God.

This kaddish (qaddîš, hallowed) is one of several similar doxologies recited on various occasions. In hallowing the name of God for 11 months, a bereaved son hopes that through the power of praise his beloved parent may find peace in God. The Kaddish does not mention the dead. Yet the mourner's Kaddish is said on every anniversary. Although Jewish tradition frowns on extreme grief — excessiveness is said to imply that the mourner is filled with greater pity than God — the Orthodox rules on various periods of mourning are complicated and quite detailed. Reform Judaism has abandoned most of the practices with which tradition has surrounded the death event, particularly those of mourning, as cumbersome, harsh, and aggravating grief rather than offering solace.

Before a Jewish Funeral

Everything done before and during the funeral is intended to honor the dead. When death is imminent no one is supposed to leave the room as dead should not left alone during the try time of traveling from one world to another and the living are supposed to witness the passing of the soul from one world to the next. Even so, often the only person at the bedside of the soon-to-be deceased is his or her spouse. According to traditional children are expected to be shielded from the unpleasant realities of disease and death even if they are in their 40s or 50s. After a person dies the eyes are closed, a sheet is placed over the head and the feet are pointed towards a doorway.

Immediately after a death, a single candle is lit and placed near the head of the deceased or many lit candles are placed around the entire body. This custom is linked to the Jewish belief that the spirit is like a light or fire. The flame on the candle represents the departed soul and “guards” the body from an invasion by negative spirits. For the same reason a “watcher” is appointed to stay with the body around the clock until the funeral. During this period no eating, drinking or smoking is allowed in the room with the dead. Speech, other than the reading of certain psalms and prayers for the deceased, is kept to a minimum.

Jewish Funeral

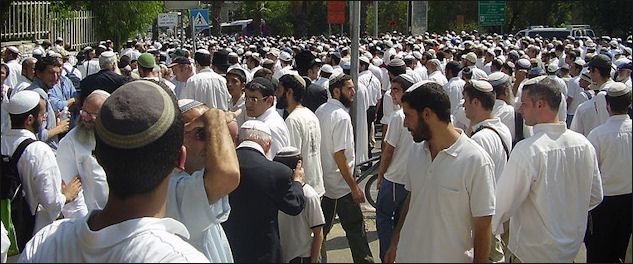

Warsaw funeral A funeral may be held at a home or a funeral chapel. Only greatly revered scholars or rabbi are given funerals in a synagogue. The funeral service consists of reading prayers and psalms, a eulogy and a special invocation as the casket is carried to a hearse. During a special ritual called the “keri’ah” , close relatives tear off their outer clothes to symbolize the intense grief they are experiencing.

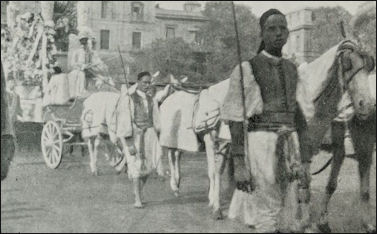

The deceased is carried to the grave, usually by children or brothers of the deceased, and biblical and liturgical verses are chanted by a rabbi as the funeral procession makes its way to the graveyard. It is customary for the procession to stop along the way to allow mourners to express their grief. At the gravesite a special prayer call the “Justification of the Divine Decree “ is read.

At the conclusion of the service the casket is lowered into the ground. A eulogy is sometimes given as the coffin is lowered into the grave. After the casket is set at the bottom of the grave, friends and family members of the deceased pay their final respects by throwing soil on the casket. Mourners then offer words of condolences to families of the deceased and a rabbi then reads “May my death be an atonement for my sins, transgressions and violations which I have sinned before you. And set my portion in the Garden of Eden, and let me merit the World to Come reserved for the righteous. Hear O Israel the Lord our God, the Lord is One.”

Immediately after the burial, the “Kaddish” , a service-ending Jewish prayer for the Dead, lead by the closest relative of the deceased, is read. It speaks of Jews looking forward to the resurrection. A stone is placed on the grave and mourners comfort one another. When the people who attended the funeral return home, they are expected to ritually wash their hands before they enter the house.

Jewish Mourning Period

After the funeral most of the mourning customs are designed to comfort and assist the survivors. During “Shiva”, the week-long period of mourning, mourners stay at home and sit on low stools, a custom which dates back to Biblical times. The only time the mourners leave home is on the Sabbath when they visit the synagogue.

There are rituals associated with “sheloshim” (a 30-day mourning period including Shiva). A less rigorous mourning period can last as long as eleven months after which time a head stone is laid at the cemetery in remembrance of the dead.

The sons of the deceased traditionally read the Kaddish every day for the first year after death. Candles are lit to mark the anniversary of that death each year. The dead are also commemorated with the yizkor service held on Yom Kippur and the final days of Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot.

The Mount of Olives is hillside in Jerusalem where Jewish tombs are situated among Christian and Muslim cemeteries. Jews believe that Jews buried here will rise to heaven after the coming of the second Messiah. The tombs of many prestigious Jews are located here; for when the Messiah come they are expected to be the first to go.

Cremation and Jews

Cremation remains taboo among most Jews, even in the non-Orthodox denominations. Both Orthodox and non-Orthodox rabbinical authorities frown on cremation. Jewish law bans the practice. Still, both the Conservative and Reform movements within Judaism let their rabbis officiate at the funerals of people who will be cremated. Orthodox groups don’t allow any such leeway. [Source: Josh Nathan-Kazis, Haaretz, July 1, 2012 )*(]

Josh Nathan-Kazis of the Israeli newspaper Haaretz wrote: No hard numbers on the practice exist. And conversations with Jewish funeral professionals from across the country suggest that the proportion of Jews who choose cremation varies widely by city. But almost all reached by the Forward agree the general trend is up. Among non-Jews, the popularity of the practice has skyrocketed in recent decades. In 2009, 38 percent of deaths in North America were cremated — up from just 15 percent in 1985, according to a report published by the Cremation Association of North America, a trade group.” )*(

“People who choose cremation often forgo other burial rituals. “Overall, and this is a number that just knocks me out, 70 percent of the [ashes] are not picked up” from funeral homes, Richard Fishman, director of the New York Department of State’s Division of Cemeteries, said. “You go to any funeral home and say, ‘How many [ashes] you got in your basement?’ and the guy will say 300, 500.” )*(

“It’s this abandonment of ritual that has even some non-Orthodox rabbis worried. “Jews have always had the tradition, going back to biblical times, to create a space on earth to mourn the dead,” said Rabbi Andy Bachman, spiritual leader of Congregation Beth Elohim, a Reform synagogue in Brooklyn. “The simplest way to put it is, if you go all the way back to Abraham’s first act after Sarah died, it was to secure a plot of land in order to bury her.”“ )*(

Cremation Becoming More Popular Among Jews

Cremation becoming increasingly popular among Jews, funeral professionals, a trend that egregiously disrespects religious edicts and thousands of years of tradition. Josh Nathan-Kazis wrote in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, “Jews are increasingly choosing to be cremated, funeral professionals say, despite Jewish law and thousands of years of tradition. The numbers are still small, relative to the non-Jewish community. But they bring with them considerable angst. [Source: Josh Nathan-Kazis, Haaretz, July 1, 2012 )*(]

Cremation becoming increasingly popular among Jews, funeral professionals, a trend that egregiously disrespects religious edicts and thousands of years of tradition. Josh Nathan-Kazis wrote in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, “Jews are increasingly choosing to be cremated, funeral professionals say, despite Jewish law and thousands of years of tradition. The numbers are still small, relative to the non-Jewish community. But they bring with them considerable angst. [Source: Josh Nathan-Kazis, Haaretz, July 1, 2012 )*(]

According to Rabbi Jeremy Kalmanofsky, a prominent Conservative rabbi in New York City, family members increasingly struggle with the wrenching question of whether to go against the wishes of dead Jews who have asked to be cremated. “I personally think that as a matter of Jewish law and tradition, that while it is good to honor the request of your dying loved ones, that it is forbidden to cremate a body, and that people are not obliged to follow those requests,” said Kalmanofsky, who leads Congregation Ansche Chesed in Manhattan. “Some congregants follow Kalmanofsky’s advice and betray their parent’s wishes, burying them instead of cremating them. Others feel they can’t. “I try not to push this button in a manipulative way, but after the Shoah, I think the thought of burning bodies is just unbearable — unbearable to me, at any rate,” Kalmanofsky said. )*(

“It’s a conundrum that promises to grow increasingly common as Jewish cremation rates rise. “I think it’s become a more accepted, preferred form of disposition,” said Mindy Botbol, president of the Jewish Funeral Directors of America and a funeral director at Arlington Heights, Ill.’s Shalom Memorial Park and Funeral Home. Neither CANA nor any other body keeps reliable statistics on the proportion of Jews who choose cremation. Estimates are difficult to compare, as some insiders count the proportion of burials in Jewish cemeteries that are of cremated remains, while others measure the proportion of deaths that result in cremations, wherever the remains end up.)*(

Prague Old Jewish Cemetery Extrapolating from the available figures, it appears that the proportions of Jews who choose cremation vary widely based on geography. Cremation rates in and around Philadelphia appear to be particularly high, according to some funeral professionals in the city. Brett Schwartz, a funeral director at Goldstein’s Rosenberg’s Raphael Sacks, a large funeral home with two locations in the Philadelphia area, said that 14 percent of the deaths they handle are cremations. Joe Levine, of the city’s other major Jewish funeral home, Joseph Levine & Sons, said that roughly 10 percent or 11 percent of the funerals he handles are cremations. “If you were to go back as little as 15 years ago, it was 3 percent,” Levine said. Congregational rabbis in the city placed the proportion of cremations at which they had officiated far lower, suggesting that Jews not affiliated with congregations are choosing cremation at a higher rate. And Levine disputed the notion, put forward by Schwartz and one other area funeral professional, that cremations are more common among Jews in Philadelphia than other cities. )*(

“Another area where experts cited relatively high rates is New York State, where Richard Fishman, director of the New York Department of State’s Division of Cemeteries, estimated that 8 percent of burials in Jewish cemeteries are burials of ashes. In Chicago, Botbol said that 6 percent to 7 percent of the deaths handled at her funeral home are cremations. Ten years ago, Fishman said, the proportion of burials in Jewish cemeteries in New York that were of ashes was “infinitesimal.” That’s changed. “It’s not scientific, but it’s definitely moving up,” he said. In Toronto, which has a large Orthodox population, William Draimin of Toronto Hebrew Memorial Park said that cremation rates were very low — 10 or 20 out of some 1,500 deaths per year. And Stan Kaplan, executive director of the Jewish Cemetery Association of Massachusetts, which owns 106 cemeteries throughout the state, said that less than 1 percent of burials in the cemeteries he overseas are burials of ashes. One funeral director in Seattle, Ross Kling of the Rosebud Funeral Service, said that 3 percent to 5 percent of Jewish deaths in the city were cremations. But he estimated that at one particular Reform synagogue the rate was as high as 15 percent. Part of that apparent upward trend may be simply due to the cultural influence exerted by the increase in cremations in general society. Botbol likened the shift to the advent of flowers at Jewish funeral services, which was not historically part of the Jewish tradition.

In Philadelphia: Bargaining for Jewish Grave Sites to Avoid Cremation

“Some not-for-profits have policies they hope will discourage cremations. Amy Koplow, executive director of the Hebrew Free Burial Association, which helps Jews afford Jewish burials, said that people hoping to save money often present her with requests for cremations. “To try to avoid cremation, we will make deals,” Koplow said. “We’ll adjust our price. If it comes down to money, in order to save somebody from being cremated, we’ll have to subsidize it more.”

“Even in Philadelphia, resistance to cremation in some quarters remains high. David Gordon, general manager of Roosevelt Memorial Park, a cemetery near Philadelphia, drew outrage in 2010 when he ran an ad in the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent advertising cremation options at the cemetery he manages. CANA cites cost as a top driver in cremation’s growing popularity in society generally. According to Barbara Kemmis, executive director of CANA, the average cost of a cremation is $1,650, while the average cost of a burial is $7,300.

Funeral directors note, however, that the cost differential is not always so large. Conservative Jews who choose cremation sometimes bury the ashes in cemeteries and hold funeral services, meaning that the extra costs involved in burials are only a matter of a few hundred dollars.

Mount of Olives Necropolis

The Mount of Olives (east of Jerusalem’s Old City Walls) is a hillside covered with Jewish, Christian and Muslim cemeteries, with 150,000 graves, and Christian churches and Arab villages. Jews believe that righteous Jews buried here will be the first to rise to the Temple Mount and after that heaven when the true Messiah arrives. Many wealthy Jews have gone through great lengths to be buried here.

▪ The Mount of Olives area is also important to Christians and Muslims. The tombs of Mary and Joseph are found here. Jesus descended down the mountain on a donkey on the first Palm Sunday. Across the Valley of Kidron next to the wall behind the Dome of the Rock is the Muslim Cemetery. Tombs of one religion or the other are often destroyed when the city has changed hand. Some 50,000 Jewish tombs were destroyed during Jordanian rule.

▪ The top of the Mount of Olives offers splendid views of the Old City, with the eastern side of the City Walls and the golden dome of the Dome of the Rock facing the viewer, and steep hills, ancient walls and rolling brown Judean desert stretching to the Dead Sea in other directions. There is an overlook with great views in front of the Seven Arches Hotel. On the slopes of the hill are, not surprisingly, lots of olive trees, some of which purportedly date back to the time of Jesus.

History of the Mount of Olives

The Mount of Olives is a sprawling, politically-sensitive necropolis with a history that stretches over three millennia. Matti Friedman of Associated Press wrote: “Jews began burying their dead on the hill that later became known as the Mount of Olives about three millennia ago. It was a convenient site a short walk from the city walls. Over the centuries, burial here became linked to a prophecy in the Book of Zecharia according to which the Messiah would approach Jerusalem from the mount, splitting it in two. Those interred on the hill, this belief posited, would be the first to be resurrected. [Source: Matti Friedman, Associated Press, Nov. 17, 2011 ]

“The mount became, and remains, a sought-after place to be buried for Jews in Israel and abroad. "As a place of burial it differs from almost every other on earth, in being, as no other is, a witness to a faith that is firm, decided and uncompromising until death," wrote Norman Macleod, a missionary, after a visit in 1864. "It is not therefore the vast multitude who sleep here, but the faith which they held in regard to their Messiah, that makes this spectacle so impressive."

“Numerous churches were also built here, associated with events in the life of Jesus. In Christian burial grounds and crypts on and around the mount visitors can find the remains of people like Princess Alice of Battenberg, mother of Prince Phillip of Britain, and Russian Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna, killed during the Russian Revolution with the rest of the czar's family.”

Between 1948 and 1967, “Jordan controlled the cemetery, paving over part of it to build a road, using gravestones to pave paths in a nearby military camp and abandoning the rest to disrepair. Reuven Mirabi." Those graves still existed. ... Sometimes the graves recount small tragedies, like that of Joseph Almozig, a Jewish conscript in the Turkish army in World War I who was charged with desertion in 1916. Almozig's broken gravestone says he was "executed by hanging at the hands of the Turkish government." Next to him is his mother, Hanina, whose tombstone from more than three decades later notes that to her right lies Joseph, her only son.

“Elsewhere in the cemetery lies Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the man responsible more than any other for reviving Hebrew as a spoken language, and a national hero in Israel. He was buried here in 1922. Nearby is Menahem Begin, buried in 1992 in a modest grave that makes no mention of the fact that he was Israel's prime minister.”

Israelis Mapping Mount of Olives Necropolis

A Jewish group in Jerusalem is using 21st-century technology to map every tombstone in the the Mount of Olives. Matti Friedman of Associated Press wrote: “The goal is to photograph every grave, map it digitally, record every name, and make the information available online. That is supposed to allow visitors to find their way in the cemetery, long a bewildering jumble of crumbling gravestones and rubble surrounded by Arab neighborhoods in east Jerusalem. Beset for many years by neglect, it is among the oldest cemeteries in continuous use in the world.

“Around 40,000 graves have been mapped so far by the team, which began work in 2008. They expect to finish recording all of the intact gravestones — an estimated 100,000 in total — by the end of next year. The rest are either so old they are unrecognizable or lie underneath later layers of burial. Mappers look at aerial photographs, consult handwritten burial records dating back to the mid-1800s, walk along the rows of graves and dig through piles of dislocated tombstones, noting names and dates. "This place has been used for burial since there have been signs of life in Jerusalem," said Moti Shamis, a member of the mapping team. "The cemetery is a mirror of the city — in wartime, we see more graves. When new groups of Jews reach the city, the names on the graves change."

“Like so much in Jerusalem, this project is linked to the city's fraught politics. The mappers are from an organization called Elad, affiliated with the settlement movement, which also works to move Jews into east Jerusalem in an attempt to prevent the city's division in any future peace deal. Elad has made it its business to develop sites of Jewish importance in east Jerusalem, reinforcing the Israeli presence in the part of the city the Palestinians want as their capital.

Prague Jewish Cemetery

The project is mapping only the Jewish cemetery, which includes several burial monuments from the time of the second Jewish Temple, about 2,000 years ago. Among the oldest graves that still bear names is one of a medieval scholar, Ovadia of Bartenura, an Italian who came to Jerusalem and died here around 1500. The work of the mappers has solved several mysteries, one of them that of the missing grave of Shmuel Ben-Bassat. Ben-Bassat was a soldier who died in combat in the war that surrounded Israel's creation in 1948. He was buried on Jan. 14 of that year, before Jewish forces lost the cemetery, along with the rest of east Jerusalem, to the Jordanian army. When Israel recaptured the Mount of Olives in 1967, the soldier's family could find no trace of him. Going through old burial records as part of the new project, the mapping team discovered a note saying he had been interred "next to Gader Gurjis and in front of Deborah, the widow of

“Some see the new mapping work in the cemetery as part of what might be termed Jerusalem's "grave wars," by which Israelis and Palestinians use their dead to bolster their claims to the holy city. Last year, Israeli authorities accused Israel's Islamic Movement of manufacturing about 300 graves as part of what was supposed to be a restoration of a Muslim cemetery in west Jerusalem. Elsewhere in the same cemetery, an Israeli initiative to build a Museum of Tolerance on land that contained human remains has drawn fierce criticism from Muslims. More recently, Palestinians have sparred with Israeli officials and archaeologists over use of part of a different Muslim cemetery just outside the walls of the Old City. "On the Mount of Olives, we have a cemetery that is undoubtedly important to the Jewish people, but we also have a battle over land," said Yonathan Mizrahi, an archaeologist whose group, Emek Shaveh, is critical of much of the Israeli activity in east Jerusalem as heedless of Palestinian residents. "The cemetery is identified as Jewish and thus as Israeli and there is an attempt to say — this is a place that needs to be under Israeli control," he said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, Library of Congress, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024