Home | Category: Judaism Beliefs

JEWISH IDEAS ABOUT WHAT HAPPENS AFTER DEATH

Grand Jewish Funeral in Cairo in 1911

There are few mentions of life after death in the Hebrew Bible. Most Jews today place more emphasis on life on Earth than on the afterlife, and their views of the afterlife are not unified. Orthodox Jews believe in a physical resurrection in which the soul and body are united and what happens after that is not known. A prevalent view among liberals is that the soul is indestructible and that all souls will return to God, even the wicked after they have served a period in purgatory. Many modern Jews view the afterlife as a kind of spiritual journey and completely discount ideas of heaven and hell.

Louis Jacobs wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: The idea of this life as a preparation for eternal bliss in the hereafter looms very large in rabbinic thinking, yet the value of this life as good in itself is not overshadowed. The second-century teacher, R. Jacob, said: "Better is one hour of repentance and good deeds in this world than the whole life of the world to come; but better is one hour of bliss in the world to come than the whole life of this world" (Avot 4:17). The same teacher said (Avot 4:16): "This world is like a vestibule before the world to come: prepare thyself in the vestibule that thou mayest enter the banqueting hall." In the same vein is the saying that this world is like the eve of Sabbath and the world to come like the Sabbath. Only one who prepares adequately on the eve of the Sabbath can enjoy the delights of the Sabbath (Av. Zar. 3a). Bliss in the hereafter is not limited to Jews. The view of R. Joshua, against that of R. Eliezer, was adopted that the righteous of all nations have a share in the world to come (Tosef., Sanh. 13:2). [Source: Louis Jacobs, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1990s, Encyclopedia.com]

See Separate Article: JEWISH FUNERALS: CUSTOMS, PRACTICES, MOUNT OF OLIVES AND CREMATION africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Encyclopædia Britannica, britannica.com/topic/Judaism; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Aish.com aish.com ; Jewish Museum London jewishmuseum.org.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Guide for the Perplexed” by Moses Maimonides, Andrea Giordani, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com ;

“Judaism: History, Belief and Practice” by Dan Cohn-Sherbok Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Choosing a Jewish Life, Revised and Updated: A Handbook for People Converting to Judaism and for Their Family and Friends” by Anita Diamant, Barrie Kreinik, et al. Amazon.com ;

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Jewish Ideas about The Afterlife

Jews have traditionally not put a lot of energy in describing what the afterlife is like. Among the few mentions in the Old Testament of what heaven is like, Abraham said, "There is a great gulf fixed; so that they which would pass from hence to you cannot; neither can they pass to us, that would come from thence."

Over time an idea that certain people resided in special “hollows” in the Underworld was formulated. The Book of Enoch, written around 200 B.C., described them as places “made that the spirits of the dead might be separated. And this division has been made for the spirits of the righteous, in which there is a bright spring of water.” Modern views of hell and heaven however are largely Christian ideas.

The traditional Jewish view of the afterlife is that most souls are purged of their sins after one year in purgatory, and then move on to paradise. Medieval Jewish writers described hell in terms that were not all that different from those expressed by Christians. Nineteenth century scholars dismissed the idea of heaven and hell but clung to beliefs in heaven. Kabbalists viewed heaven and hell as too static and developed a more dynamic system that included elements of reincarnation, which are regarded as chances for some to redeem themselves and could take place a maximum of three times.

Development and Early History of Jewish Ideas about The Afterlife

Emanation Bart D. Ehrman, a University of North Carolina professor, a leading New Testament scholar, and an evangelical-turned-agnostic, wrote in Time: “Unlike most Greeks, ancient Jews traditionally did not believe the soul could exist at all apart from the body. On the contrary, for them, the soul was more like the “breath.” The first human God created, Adam, began as a lump of clay; then God “breathed” life into him (Genesis 2: 7). Adam remained alive until he stopped breathing. Then it was dust to dust, ashes to ashes. Ancient Jews thought that was true of us all. When we stop breathing, our breath doesn’t go anywhere. It just stops. So too the “soul” doesn’t continue on outside the body, subject to postmortem pleasure or pain. It doesn’t exist any longer. The Hebrew Bible itself assumes that the dead are simply dead — that their body lies in the grave, and there is no consciousness, ever again. [Source: Bart D. Ehrman,, Time magazine, May 9, 2020]

It is true that some poetic authors, for example in the Psalms, use the mysterious term “Sheol” to describe a person’s new location. But in most instances Sheol is simply a synonym for “tomb” or “grave.” It’s not a place where someone actually goes. And so, traditional Israelites did not believe in life after death, only death after death. That is what made death so mournful: nothing could make an afterlife existence sweet, since there was no life at all, and thus no family, friends, conversations, food, drink — no communion even with God. God would forget the person and the person could not even worship. The most one could hope for was a good and particularly long life here and now.

“But Jews began to change their view over time, although it too never involved imagining a heaven or hell. About two hundred years before Jesus, Jewish thinkers began to believe that there had to be something beyond death — a kind of justice to come. Jews had long believed that God was lord of the entire world and all people, both the living and the dead. But the problems with that thinking were palpable: God’s own people Israel continually, painfully, and frustratingly suffered, from natural disaster, political crises, and, most notably, military defeat. If God loves his people and is sovereign over all the world why do his people experience so much tragedy? Some thinkers came up with a solution that explained how God would bring about justice, but again one that didn’t involve perpetual bliss in a heaven above or perpetual torment in a hell below.

This new idea maintained that there are evil forces in the world aligned against God and determined to afflict his people. Even though God is the ultimate ruler over all, he has temporarily relinquished control of this world for some mysterious reason. But the forces of evil have little time left. God is soon to intervene in earthly affairs to destroy everything and everyone that opposes him and to bring in a new realm for his true followers, a Kingdom of God, a paradise on earth. Most important, this new earthly kingdom will come not only to those alive at the time, but also to those who have died. Indeed, God will breathe life back into the dead, restoring them to an earthly existence. And God will bring all the dead back to life, not just the righteous. The multitude who had been opposed to God will also be raised, but for a different reason: to see the errors of their ways and be judged. Once they are shocked and filled with regret — but too late — they will permanently be wiped out of existence.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “What Jesus Really Said About Heaven and Hell” time.com/

Judaism and the Soul

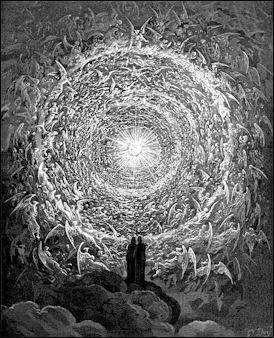

Christian view of heaven

by Canto Gustave The Jewish concept of the soul has changed a great deal over time; it has been influenced by cultures to which Jews have been in contact; and it doesn’t arise in the Old Testament until the Book of Daniel, which was written around the 2nd century B.C. In very ancient times it appears that the Jews believed that a person ceases to exist after death. Throughout the Old Testament, God delivers rewards — such as wealth, freedom and prosperity — to the living rather than promising rewards in the Afterlife.

As the Jews suffered and it seemed the good and righteous were not always rewarded while they were alive, a concept of a soul and afterlife began. During the 6th, 5th, 4th and 3rd centuries B.C. , Jews came in contact with Persians, Egyptians and Greek and some Jewish sects began incorporating their ideas about the afterlife into their own. Some sects raised the idea that people who had been shortchanged in their lifetimes with a proportionally high amount of hardships, could be resurrected for another, better life. Other sects began raising the idea of an Underworld, similar to Greek Hades.

Around the time Jesus appeared, a period of great upheaval in Palestine, the ideas of separate body and soul and a Satan became more prominent. Some Jewish sects also developed beliefs in angles, demons, and magic but the dominant priestly caste stayed true to the Torah and the Temple rituals. A more mystical and spiritual concept of the soul developed in medieval times with the creation of the Kabbalah (mystical text), which asserted the soul was created in God?s image and it developed through a yin-yang type relationship with God that an individual could nurture through knowledge, prayer and meditation. Kabbalistic theology however never really caught on with the Jewish masses.

Jewish Views on Heaven and the Afterlife

There are few mentions of life after death in the Hebrew Bible, and Jews have traditionally not put a lot of energy in describing what the afterlife is like. Among the few mentions in the Old Testament of what heaven is like, Abraham said, "There is a great gulf fixed; so that they which would pass from hence to you cannot; neither can they pass to us, that would come from thence."

Over time an idea that certain people resided in special “hollows” in the Underworld was formulated. The Book of Enoch, written around 200 B.C., described them as places “made that the spirits of the dead might be separated. And this division has been made for the spirits of the righteous, in which there is a bright spring of water.” Modern views of hell and heaven however are largely Christian ideas.

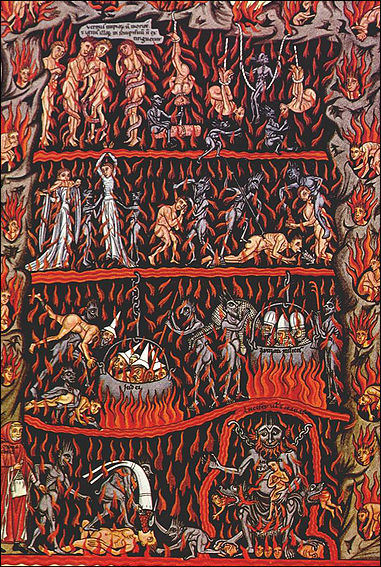

Christian view of hell by Hortus Deliciarum

with Jews (in hats) in the third row from the top The traditional Jewish view of the afterlife is that most souls are purged of their sins after one year in purgatory, and then move on to paradise. Medieval Jewish writers described hell in terms that were not all that different from those expressed by Christians. Nineteenth century scholars dismissed the idea of heaven and hell but clung to beliefs in heaven. Kabbalists viewed heaven and hell as too static and developed a more dynamic system that included elements of reincarnation, which are regarded as chances for some to redeem themselves and could take place a maximum of three times.

Most Jews today place more emphasis on life on Earth than on the afterlife, and their views of the afterlife are not unified. Orthodox Jews believe in a physical resurrection in which the soul and body are united and what happens after that is not known. A prevalent view among liberals is that the soul is indestructible and that all souls will return to God, even the wicked after they have served a period in purgatory. Many modern Jews view the afterlife as a kind of spiritual journey and completely discount ideas of heaven and hell.

Sheol and Hell

Early Jews developed the concept of Sheol, an Underworld where the all dead resided in a kind of semi-existence. Genesis, 1 Kings, Psalms and Job all mention Sheol. Eccles 9:10 describes it as a place in which "you are bound, there is neither dying nor thinking neither understanding nor wisdom." When Jacob concluded his beloved son was dead, he moaned, “I shall go down to Sheol to my son, mourning.” The concept of Sheol was partly based on the Greco-Roman belief of Hades, a dreary and depressing place where people went after they died. The Pharisees, a Jewish sect that lived around the time of Jesus, embraced the Greco-Roman idea of heaven as place with distinct “levels,” or areas. In the 2nd century B.C. when the Hebrew scriptures were translated to Greek, the word Hades was used instead of Sheol.

Isaiah predicts a punishment of fire for the wicked and Daniel describes “shame and everlasting contempt” for evildoers. There is no mention of Hell in the Old Testament as a permanent place of punishment for the wicked but Hades is represented as a temporary abode for the wicked. The Book of Enoch reads: “And this has been made for sinners when they die and are buried in the earth and judgment has not been executed upon them in their lifetime. Here their spirits shall be set apart in great pain, till the great day of judgment, scourging, and torments of the accursed for ever.”

Judaism widely reject a literal interpretation of hell. In the 18th century the influential Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn reasoned that hell couldn’t exist because a punishment of eternal suffering was is incompatible with God’s mercy.

Jewish Resurrection

medieval Jewish view of the Resurrection Bodily resurrection is official dogma of Judaism but it is a doctrine that many modernist Jews have trouble accepting. It was incorporated into Judaism around 600 B.C. presumably from the Zoroastrian Persians. See Zoroastrianism.

In the Old Testament, Isaiah 26:19 reads: “dead corpses shall rise awake and sing.” After the destruction of the Temple in 586 B.C., the Jews were exiled to Babylonia, where the Prophet Ezekiel predicted the resurrection of the Jews and described a field of dry bones that God told to "come together bone by bone" and lived again.

Jewish concepts of resurrection are believed to have been influenced by the Greeks and Egyptians. Judaism doesn’t talk much about judgement, which is different Christianity and Islam. It talks a little about some people being blessed and some being condemned but it doesn’t really have any episodes in which people stand before God, who judges them and sends them to heaven or hell.

During the period of upheaval that occurred after Greeks desecrated the Temple in 167 B.C. the idea of a resurrection gained more credibility. According to the Book of Daniel, written 165 B.C., “Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt. Those who are wise shall shine like the brightness of the sky, and those who lead many to righteousness, like the stars forever and ever.”

The Jewish historian Josephus wrote that the Pharisees, a Jewish sect, “believe that souls are endowed with immortal power and that somewhere under the earth rewards and punishment will be meted out to them, according to whether they have lived vice or virtue. The former will be condemned to perpetual imprisonment, but the others will be allowed to return to life.”

Resurrection, End of the World and the Messiah

The Jewish concept of afterlife is closely tied with the coming of the Messiah and the end of the world. A prevalent view among Jews, which dates back primarily to the Middle Ages, is that when the Messiah comes the dead will be resurrected and reunited with their bodies in a paradise-like kingdom of God near Jerusalem. Afterwards there will be a judgment in which the wicked will be destroyed forever and the faithful will exist with God forever in a bodiless state.

The concept of disaster followed by redemption help the Jews survive as a people and was the cornerstone of beliefs about a messiah.

According to Enoch 5:7-9, “But for the elect there shall be light and grace and peace, and they shall inherit the earth...And their lives shall be increased in peace. And the years of their joy shall be multiplied, in eternal gladness and peace, all the days of their life.”

See Separate Article: MESSIAHS IN JUDAISM africame.factsanddetails.com

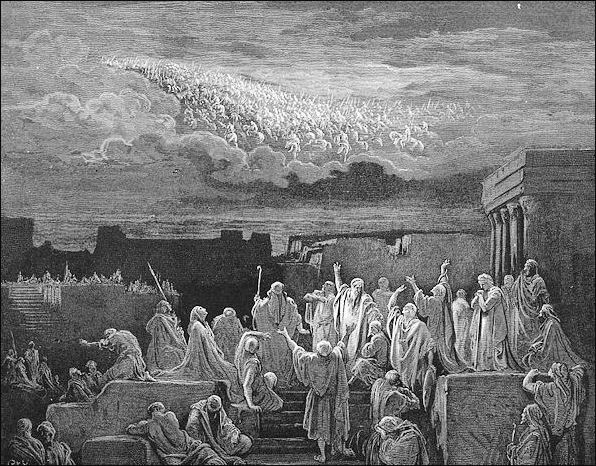

Army Appears in the Heavens

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, Library of Congress, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024