Home | Category: Judaism and Jews / Judaism Beliefs / Judaism, Jews, God and Religion

JUDAISM

Yehuak, the original Jewish word for God

Judaism is the religion of the Jewish people. It is a monotheistic faith affirming that God is one, the creator of the world and everything in it. In Judaism faith is less a matter of affirming a set of beliefs than of trust in God and fidelity to his law. Faith is thus primarily expressed "by walking in all the ways of God" (Deut. 11:22). [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s Encyclopedia.com]

The term Judaism can be used to refer both to the religion and the community of people that follow it. There are great differences in beliefs across the various communities of Jews but there are some commonalities shared by all Jewish people. According to the BBC: “Jews believe that God appointed the Jews to be his chosen people in order to set an example of holiness and ethical behavior to the world. Jews believe that there is only one God with whom they have a covenant. In exchange for all the good that God has done for the Jewish people, Jewish people keep God’s laws and try to bring holiness into every aspect of their lives. Judaism has a rich history of religious text, but the central and most important religious document is the Torah. Jewish traditional or oral law, the interpretation of the laws of the Torah, is called halakhah. Jews worship in Synagogues. Spiritual leaders are called Rabbis. Six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust in an attempt to wipe out Judaism. There are many people who identify themselves as Jewish without necessarily believing in, or observing, any Jewish law. [Source: BBC |::|]

Judaism remains an important religion even though it has a relatively small number of followers. There is an emphasis on divine will expressed in laws and ecclesiastical authority has traditionally been weak while written laws have been strong. In its conservative form Judaism has a number of rituals, laws and rules which are expected to be followed to the smallest detail but often the basis of these rituals is nothing more than tradition. Jewish scholarship has often been oriented towards interpreting these laws in a changing world and Judaism itself has been described a “reflection” upon Jewish history and tradition.

Websites and Resources: Judaism Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Encyclopædia Britannica, britannica.com/topic/Judaism; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Choosing a Jewish Life, Revised and Updated: A Handbook for People Converting to Judaism and for Their Family and Friends” by Anita Diamant, Barrie Kreinik, et al. Amazon.com ;

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com ;

“The Gifts of the Jews: How a Tribe of Desert Nomads Changed the Way Everyone Thinks and Feels” by Thomas Cahill Amazon.com ;

“The Antiquities of the Jews”

by Flavius Josephus, Allan Corduner, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Jews: A History” by John Efron, Steven Weitzman, et al. Amazon.com

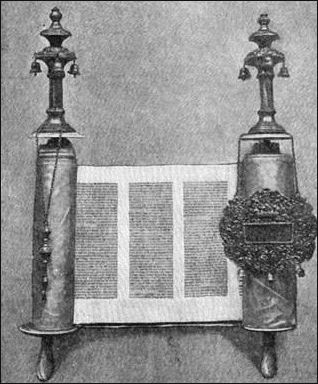

Judaism and Torah

Torah (without the The) can refer to Law of Judaism itself and not just to the scroll or book that houses it. Louis Jacobs wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica:: In modern usage the terms "Judaism" and "Torah" are virtually interchangeable, but the former has on the whole a more humanistic nuance while "Torah" calls attention to the divine, revelatory aspects. The term "secular Judaism" — used to describe the philosophy of Jews who accept specific Jewish values but who reject the Jewish religion — is not, therefore, self-contradictory as the term "secular Torah" would be. (In modern Hebrew, however, the word torah is also used for "doctrine" or "theory" (e.g., "the Marxist theory"), and in this sense it would also be logically possible to speak of a secular torah. In English transliteration the two meanings might be distinguished by using a capital T for the one and a small t for the other, but this is not possible in Hebrew which knows of no distinction between small and capital letters.) [Source: Louis Jacobs, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1990s, Encyclopedia.com]

Torah (without the The) can refer to Law of Judaism itself and not just to the scroll or book that houses it. Louis Jacobs wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica:: In modern usage the terms "Judaism" and "Torah" are virtually interchangeable, but the former has on the whole a more humanistic nuance while "Torah" calls attention to the divine, revelatory aspects. The term "secular Judaism" — used to describe the philosophy of Jews who accept specific Jewish values but who reject the Jewish religion — is not, therefore, self-contradictory as the term "secular Torah" would be. (In modern Hebrew, however, the word torah is also used for "doctrine" or "theory" (e.g., "the Marxist theory"), and in this sense it would also be logically possible to speak of a secular torah. In English transliteration the two meanings might be distinguished by using a capital T for the one and a small t for the other, but this is not possible in Hebrew which knows of no distinction between small and capital letters.) [Source: Louis Jacobs, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1990s, Encyclopedia.com]

A further difference in nuance, stemming from the first, is that "Torah" refers to the eternal, static elements in Jewish life and thought while "Judaism" refers to the more creative, dynamic elements as manifested in the varied civilizations and cultures of the Jews at the different stages of their history, such as Hellenistic Judaism, rabbinic Judaism, medieval Judaism, and, from the 19th century, Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform Judaism. (The term Yidishkeyt is the Yiddish equivalent of "Judaism" but has a less universalistic connotation and refers more specifically to the folk elements of the faith.)

It is usually considered to be anachronistic to refer to the biblical religion (the "religion of Israel") as "Judaism," both because there were no Jews (i.e., "those belonging to the tribe of Judah") in the formative period of the Bible, and because there are distinctive features which mark off later Judaism from the earlier forms, ideas, and worship. For all that, most Jews would recognize sufficient continuity to reject as unwarranted the description of Judaism as a completely different religion from the biblical.

The evolution from Hebraism (a religion based only on the scriptures of the Old Testament) to Judaism (with rabbis and religion doctrine interpreted by these rabbis) was a slow transformation that began in the destruction of the Second Temple (A.D. 70) and the compilation of the “Mishnah” (Judaism’s first major canonical document following the Bible) in the A.D. second century. During this time Judaism absorbed new ideas and faced new problems, many resulting from war and dislocation.

Alexandria was a center of Jewish intellectual life as well as Greek, Roman and Christian intellectual thought. Jewish scholars such as Philo of Alexandria were deeply influenced by Greek philosophy, which helped them find a vocabulary and ideas to address some of the more abstract concepts of their religion especially when it came to God. By contrast scholars that stayed close to their roots in Palestine stayed truer to the Bible and conceptualized God in more human and anthropomorphic terms. The evolution of these two methods of approaching Judaism led to articulation of the more mysterious aspects of Judaism and a codification of its laws.

The creation of Judaism was the work of rabbis who reconstructed the religion of the Jews by interpreting the Torah in a world without a Temple based on oral traditions, families and synagogues. The record of these rabbis formed the basis for the Mishnah and the Talmud.

In the Middle Ages there were many Jewish sects. In some cases each had its own Talmud. In time the the Babylonian Talmud predominated over the others. These were later organized into codes of which the code of Maimonides (1135-1204) and Joseph Caro (1488-1575), known as “Shulchan Aruch” , became the most important.

Rabbinic Judaism

Israeli soldier with tefilin

Rabbinic Judaism is historically the most widespread and most representative form of Judaism. Jacob Kat wrote in the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences: It accepts the canonized books of the Hebrew Bible as divine revelation and accords them uncontested authority. The same holds true of the substance of the oral tradition. Both written and oral law, however, are not simple sources to be directly consulted by the believer for guidance. Their interpretation lies in the hands of experts, that is, the sages or rabbis who are, in a more or less formal fashion, authorized by their predecessors. This uninterrupted transmission of oral law from teacher to student since the time of Moses is one of the cardinal tenets of the belief system of Rabbinic Judaism. [Source: Jacob Kat. International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Encyclopedia.com]

The rules and content of interpretation are themselves included in the tradition and are relatively stringent when they touch upon practical affairs, such as moral, ritual, or civic matters (halachah). In the area of belief and dogma, however, the body of teaching (agadah) is less strictly defined in both method and in content. Both types of teachings were incorporated into the basic texts of Rabbinic Judaism — the Mishnah and the Gemara, which together constitute the Talmud (both the Palestinian version, edited in the third century, and Babylonian, edited in the fifth). The Mishnah is a terse summary, in Hebrew, of the full corpus of Jewish law as it had crystallized by the second century of the Christian era. The Gemara is a quasistenographic report, in Aramaic, of the discussions and lengthy elaborations of the Mishnah as they occurred in the Palestinian and Babylonian academies in the subsequent centuries. The text is further interspersed with lengthy discussions of formulated exegesis and folklore. The whole body of religious teachings is commonly designated by the name torah, a term which strictly speaking refers only to the first five books of the Old Testament, that is, the Pentateuch.

The authoritative Mishnah and Gemara were subjected to reinterpretation, partly as a consequence of the inherent dialectic of textual interpretation and partly as an outgrowth of religious–judicial decisions on new and problematic realities. From commentaries, novellae, and responsa, layer after layer was added to the law, and as a consequence the halachah was repeatedly codified. Correspondingly, religious thinkers brought its theoretical teachings into alignment with various contemporary philosophical systems. Both intellectual activities — juridical and philosophical — were dependent on interpretation of given sacred texts by qualified authorities and remained scholastic in nature.

See Separate Article: DEVELOPMENT OF RABBINIC JUDAISM: A.D. FIRST TO FIFTH CENTURIES africame.factsanddetails.com

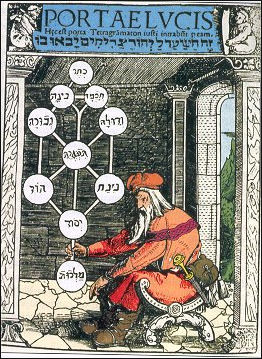

Kabbalah

Kabbalah Tree of Life

from Medieval times The Kabbalah is the name given to Jewish mystical knowledge passed down orally from generation to generation and hinted at in the Talmud. It is concerned with finding hidden meaning in the Scriptures, reaching elevated planes and ecstatic states, delving into magic, and speculating on the coming of the Messiah. Kabbalah has been compared to Sufism, Islamic mysticism. The word Kabbalah roughly means “esoteric tradition” and more precisely “what is receives,” a reference to Moses receiving the laws of God at Mt. Sinai, and a word widely used on modern Israel to describe the reception desk at hotels, among other things.

Despite claims that Kabbalah is a form of mystical teaching practiced by Moses it in fact has it origins in medieval Europe. In 13th century Spain and southern France, Jewish scholars claimed they possessed secret scriptural knowledge that had originated with Moses and had been passed down orally over the centuries. These scholars and exegetes, later known as kabbalists, were focused primarily on two sections of the Torah that were forbidden by the Talmud to be discussed publically. The first is the description of Creation in Genesis and the second is a description in the Book of Ezekial of Ezekial’s vison of a cosmic chariot.

Kabbalah emerged at a time when Judaism was dominated by rabbis who set rigid, detailed laws that all Jews were expected to follow unquestioningly. Judaism at that time was based in moral rationalism and included a code of ethics. It emphasized the primacy of charity and discredited esoteric beliefs and pursuing deep issues such as the meaning of God. Kabbalists sought not only to define and characterize God but also to tap into his spiritual and cosmological power, a pursuit regarded by purists as heretical.

See Separate Article: KABBALAH, MYSTICAL JUDAISM AND THEIR HISTORY africame.factsanddetails.com

Judaism in Israel

Only Orthodox Judaism functions as an established religion in Israel. Other forms of the religion—such as the Reform and Conservative sect to which many American Jews belong—are not recognized and not given much respect by the Israeli government or ordinary Israelis. Conversions performed by Reform and Conservative rabbis are not recognized in Israel.

Since around 80 percent of Israeli do not regard themselves as Orthodox they are lumped together as secular Jews. Many of these are non-religious but the majority regard themselves as practicing Jews. Although they do not regularly visit synagogues, they pray, light candles and engage in Jewish rituals to varying degrees. They have been educated in Jewish history in school and accept rabbinical authority on matters like circumcision, marriage, divorce and death.

To get a sense of how little influence Judaism has a many Israelis, check out the beaches, which are often crowded on the Sabbath and have people at them on solemn holidays like Yom Kippur.

There are around 20,000 synagogues in Israel in addition to religious councils in most cities and large towns. The main religious authority, the rabbinate, controls courts that make decisions about many legal matters, and even dietary matters by naming foods that are kosher. It is controlled by Orthodox Jews. Only Orthodox rabbis are allowed to perform marriages, conversions and burials. Even secular Jews regard Orthodox Jews as “real” Jews and are dismissive of liberal Jews.

Judaism Beliefs

Basic beliefs of Judaism: 1) Existence in one God (Monotheism); 2) Covenant with Israel; 3) Revelation of Torah; 4) Obedience to God s Law; 5) Historical Providence; 6) Redemption. 7) The soul (nefesh) of the deceased is thought to return to God; 8) Accuracy of the Hebrew Bible; 8) belief in the Prophets; 9) Belief that a messiah will come; and 10) belief in the last judgment and resurrection.. [Source: BBC |::|; Encyclopedia.com]

Numerous efforts have been made to crystalize the core beliefs of Judaism. Few of these efforts have been accepted by all Jews. Many Jews, however, accept the Thirteen Principals of Judaism as outlined by Maimonides, one of the great scholars in Jewish history. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

The Thirteen Principles (Thirteen Articles of Faith) of Maimonides are regarded as the basic dogma of Judaism. They are: 1) The existence of God, the Creator of All Things; 2) His absolute unity; 3) His incorporeality; 4) His eternity; 5) The obligation to serve and worship him alone; 6) The existence of prophecy; 7) The superiority of the Prophecy of Moses above all others; 8) The “Torah” is God’s revelation to Moses; 9) “The Torah” is immutable; 10) God’s omniscience and foreknowledge; 11) Rewards and punishments according to one’s deeds; 12) The coming of the Messiah; 13) The resurrection of the dead.

See Separate Article: JUDAISM BELIEFS africame.factsanddetails.com

Jewish Laws and Doctrines

The primary responsibility of a Jew has traditionally been to unquestioningly follow Jewish laws. Jews were expected to rejoice in following these laws and constantly be looking for new ways to apply them in their everyday life, with rabbis acting as lawyers.

Jews place great importance on abiding by the laws and rules set forth in the Torah and regard it as a religious duty to follow them. Jewish Law is called the “Halakah” , which literally means “that by which one walks.” It is comprised of the laws laid out in the Torah and Talmud and interpretations of these laws. “Torah she-bi-khtav” is the written law.

Kosher Gummi Bears According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: In Judaism faith is less a matter of affirming a set of beliefs than of trust in God and fidelity to his law. Faith is thus primarily expressed "by walking in all the ways of God" (Deut. 11:22). These ways are specified in God's revealed law, which the rabbis, or teachers, appropriately called the Halakhah (walking). The commandments of the Halakhah embrace virtually every aspect of life, from worship to the most mundane aspects of daily existence. The precise details of the Halakhah are but adumbrated in the Torah, and they require elaboration to determine their contemporary applicability. This process is ongoing, for the Torah must be continually reinterpreted to meet new conditions, and the rabbis developed principles to allow this without violating its sanctity. The modern world has thus witnessed the emergence alongside traditional, or Orthodox, Judaism various movements—Reform, Conservative, and Reconstructionist—that have introduced new criteria for the interpretation of the Torah and for Jewish religious responsibility. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Judaism was originally a theocratic religion like Islam in which there was a set of religious laws for a Jewish kingdom. After the diaspora, laws and rules were established that became a way of defining and uniting Jewish communities.

Almost every aspect of a Jew’s life and every act of everyday living — from eating to dressing to working — has some religious aspect attached to it. Almost all aspect of life are governed by strict religious practices and rules. Jews regard it as a duty to observe the Sabbath and Jewish holidays, eat certain foods, performing specific rituals like the lighting of candles, and attending the synagogue. The are special blessing that are uttered when an Jew eats, smells a flower or puts on clothes in the morning.

Maimonides: The 613 Mitzvot

According to Jewish tradition, the Torah contains 613 commandments. This tradition is first recorded in the A.D. 3rd century when Rabbi Simlai mentioned it in a sermon that is recorded in Talmud Makkot Although the number 613 is mentioned in the Talmud, its real significance increased in later medieval rabbinic literature, including many works listing or arranged by the mitzvot. The most famous of these was an enumeration of the 613 commandments by Maimonides, which are divided into 248 Positive Mitzvos and 365 Negative Mitzvos. [Source: Wikipedia]

The first of the 248 Positive Mitzvos are:

P 1 — Believing in G-d

P 2 — Unity of G-d

P 3 — Loving G-d

P 4 — Fearing G-d

P 5 — Worshiping G-d

P 6 — Cleaving to G-d

P 7 — Taking an oath by G-d's Name

P 8 — Walking in G-d's ways

P 9 — Sanctifying G-d's Name

P 10 — Reading the Shema twice daily

Moses with Ten Commandments

The first of the 365 Negative Mitzvos

N 1 — Not believing in any other G-d

N 2 — Not to make images for the purpose of worship

N 3 — Not to make an idol (even for others) to worship

N 4 — Not to make figures of human beings

N 5 — Not to bow down to an idol

N 6 — Not to worship idols

N 7 — Not to hand over any children to Moloch

N 8 — Not to practice sorcery of the ov

N 9 — Not to practice sorcery of the yidde'oni

N10 — Not to study idolatrous practices

Among some of the other Negative Mitzvos are:

N330 — Not have relations with one's mother

N331 — Not have relations with one's father's wife

N332 — Not have relations with one's sister

N333 — Not have relations with daughter of father's wife if sister

N334 — Not have relations with one's son's daughter

N335 — Not have relations with one's daughter's daughter

N336 — Not have relations with one's daughter

N337 — Not have relations with a woman and her daughter

N338 — Not have relations with a woman and her son's daughter

N339 — Not have relations with a woman and her daughter's daughter

N340 — Not have relations with one's father's sister

N341 — Not have relations with one's mother's sister

N342 — Not have relations with wife of father's brother

N343 — Not have relations with one's son's wife

N344 — Not have relations with brother's wife

N345 — Not have relations with sister of wife (during her lifetime)

Others:

N 25 — Not increasing wealth from anything connected with idolatry

N 29 — Not fearing or refraining from killing a false prophet

N 32 — Not regulating one's conduct by the stars

N 36 — Not consulting a necromancer who uses the ov

N 40 — Men not wearing women's clothes or adornments

N 43 — Not shaving the temples of the head

N 57 — Not destroying fruit trees in time of siege

N 73 — Not to be intoxicated when entering Sanctuary; and (ctd)

N 92 — Not to slaughter a blemished animal as a korban

N 98 — Not to offer leaven or honey upon the Altar

N171 — Not to tear out hair for the dead

N173 — Not to eat any unclean fish

N175 — Not to eat any swarming winged insect

N184 — Not to eat blood

N213 — Not to gather single fallen grapes during the vintage

N234 — Not demanding payment from a debtor known unable to pay

N235 — Not lending at interest

N295 — Not accepting ransom from an unwitting murderer

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Maimonides: The 613 Mitzvot in the Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

Jewish Morality and Approach Towards Life

Paul Mendes-Flohr wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: Judaism does not distinguish between duties toward fellow human being and duties toward God. The Hebrew Bible and the rabbis regard moral and religious duties as inseparable. The emphasis is on attaining holiness, on "walking in God's ways" (Deut. 10:12–13), thus allowing his presence to dwell in one's midst. Through Moses, God told the Children of Israel, "You shall be holy, for I, the Lord your God, am holy" (Lev. 19:2), which is recited today by observant Jews in their morning and evening prayers. This commandment is followed immediately by the injunction to honor one's parents and to observe the Sabbath. The weave of moral and ritual duties is maintained in a long list of commandments, from measures to aid the poor and secure their dignity to proper worship at the Temple, from fairness in commerce to the avoidance of pagan rites, from respect for the stranger to the sanctity of the firstfruits (Lev. 19:3–37), the earliest products of the harvest that are offered to God. A person attains holiness by observing the commandments and laws of God. As God is manifest only through his deeds, so a person is beckoned to imitate those deeds (Deut. 10:17–19). [Source:Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

The prophets, and the rabbis after them, typically warned that ritual piety unaccompanied by moral deeds is unacceptable to God. As the prophet Micah taught, "With what shall I approach the Lord, Do homage to God on high? Shall I approach Him with burnt offerings? … He has told you, O man, what is good / And what the Lord requires of you: Only to do justice / And to love goodness / And to walk humbly with your God …" (Mic. 6:6–8). But while upholding the primacy of morality over ritual, it was not the intention of Micah, or of any other prophet, to distinguish moral from religious virtue. The biblical conception of social responsibility as the axis of the ethical life was incorporated by the rabbis into the Halakhah. The rabbis elaborated biblical injunctions, codifying in great detail alongside the Jew's ritual duties the ethical principles of justice, equity, charity, and respect for the feelings and needs of others.

When asked to identify the overarching principle of the Torah, the rabbis pointed to its moral dimension. Hence, according to a Midrash on Leviticus 19:18, "Rabbi Akiva [c. 50–c. 136] said of the command, 'You shall love your neighbor as yourself,' that is 'a great principle of Torah.'" Rabbi Hillel (c. 70 B.C.–c. 10 A.D.) formulated the same principle with psychological insight: "What is hateful unto yourself do not to your fellow human being. This is the entire Torah, the rest is commentary. Go and study." Implicit in these encapsulations of biblical morality is that the ethical life requires sensibilities that often must go, as the rabbis would put it, "beyond the letter of the law." To love one's neighbor or to avoid treating one's neighbor in a manner that one would find repugnant — offensive, hurtful, humiliating — when done to oneself, requires a sensitivity that cannot be legislated.

The religious significance of the moral teachings of the Torah was summarized by a sixteenth-century rabbinical scholar from Prague, Judah Loew, popularly known as the Maharal. Through adhering to the moral teachings of the Torah, the Maharal taught, a person imitates God's ways and thus realizes his or her destiny as a being created in the image of God. Moral behavior, therefore, draws a person to God. Conversely, immoral conduct distances a person from God. The nineteenth-century German rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch observed that "the Torah teaches us justice towards our fellow human beings, justice towards the plants and animals and the earth, justice towards our own body and soul, and justice towards God who created us for love so that we may become a blessing for the world."

Following Jewish Laws Sincerely Versus Simply Going Through the Motions

YHWH on the Mesha Stele

Dara Lind of Vox wrote: Some jews believe that “the point of their Judaism wasn't what they believed but what they did. To orthodox Jews, this is monstrous: a sickness of modernity. They can't abide the idea of Jews going through the motions to serve a deity in whom they may not believe; to them, this is precisely how Judaism gets reduced from a religion to a culture. [Source: Dara Lind, Vox, April 22, 2016 |=|]

“And to many Jews who grew up being told to follow at least some of the commandments without any way of reconciling those actions with their beliefs — Jews like my father and the parents of the kids he taught at Sunday school, Jews like many of my peers — it's pointless. They find no meaning in the rituals themselves, and "because your ancestors did it" doesn't carry much more weight than "because I said so." To them, this is the religion they abandon, even if they acknowledge at least some of Jewish culture — the food, the kvetching, the Yiddish — as their own. But few people are introspective enough to know the precise origins of every trait they've inherited from their parents or been raised with in their homes. People can't always judge what, in their upbringing, was Jewish and what was not. |=|

“When people slough off orthopraxy as meaningless ritual, they're putting practices and customs in a mental attic, in a box labeled "Judaism" — and leaving it at that. They're cutting off an alternative mode of inquiry: thinking about what they have inherited because of Judaism. "I'm far more Jewish during Passover than I am during any other time of year" This sounds like trivializing Judaism, the faith of my ancestors, a culture that has sustained my people for thousands of years. I'd argue that even if it were trivializing, it wouldn't be less so than simply foregoing the practice entirely and dooming it to die. |=|

“But it isn't. It's orthopraxy. Judaism roots its values in obligations. You must give tzedakah. You must honor the Sabbath as a day of rest and study. You must be present in the temple on the High Holidays to seek forgiveness for the misdoings of the past year. You must, for eight days, eat matzah — "the bread of affliction" that is also the bread of freedom. And sure, you can put peanut butter on it. You can spend eight days eating quinoa and rice. As for me, I'd need a better reason to abandon the stricter rules about kitniyot than that following them is hard.” |=|

Judaism, a Faith for a Community and Family to Live By

According to the BBC: Jews believe that God appointed the Jews to be his chosen people in order to set an example of holiness and ethical behaviour to the world. Jewish life is very much the life of a community and there are many activities that Jews must do as a community. For example, the Jewish prayer book uses WE and OUR in prayers where some other faiths would use I and MINE. Jews also feel part of a global community with a close bond Jewish people all over the world. A lot of Jewish religious life is based around the home and family activities. [Source: BBC |::|]

“Judaism is very much a family faith and the ceremonies start early, when a Jewish boy baby is circumcised at eight days old, following the instructions that God gave to Abraham around 4,000 years ago. Many Jewish religious customs revolve around the home. One example is the Sabbath meal, when families join together to welcome in the special day. |::|

“Being part of a community that follows particular customs and rules helps keep a group of people together, and it's noticeable that the Jewish groups that have been most successful at avoiding assimilation are those that obey the rules most strictly - sometimes called ultra-orthodox Jews. Note: Jews don't like and rarely use the word ultra-orthodox. A preferable adjective is haredi, and the plural noun is haredim.” |::|

Almost everything a Jewish person does can become an act of worship. Because Jews have made a bargain with God to keep his laws, keeping that bargain and doing things in the way that pleases God is an act of worship. And Jews don't only seek to obey the letter of the law - the particular details of each of the Jewish laws - but the spirit of it, too. A religious Jew tries to bring holiness into everything they do, by doing it as an act that praises God, and honours everything God has done. For such a person the whole of their life becomes an act of worship. Judaism is a faith of action and Jews believe people should be judged not so much by the intellectual content of their beliefs, but by the way they live their faith - by how much they contribute to the overall holiness of the world.” |::|

Cantradictions and Arguments — a Fixture of Judaism

The Torah and Hebrew Bible are full of contradictory messages as are the New Testament and the Koran and other religious text. In Deuteronomy worshippers of Yahweh are told: “You shall annihilate them — the Hittites and the Amorites, the Canaanites and Perizzites and the Hivites and the Jebsuites — just as the Lord your God has commanded.” While in the book of Judges, an Israelite military leader proposes more tolerance towards the Ammonites: “Should you not possess what your god Chemosh gives you to possess? And should we not be the ones who possess everything that our god Yahweh has conquered for our benefit.” The Koran arguably is filled with even more contradictions. In one part of the Koran, Muslims are told to “kill the polytheistic wherever you find them.” But in a another passage they are told: “To you be your religion; to me my religion.”

Prophecy is regarded as concrete manifestation of the Jewish religion and according to some Jewish thinkers a fate that Jews alone have. The idea that the “Torah” is immutable addresses claims by other religions, particularly Christianity that it goes a step further than Judaism.

Dara Lind of Vox wrote: “Judaism is also a religion of jurisprudence. Often, that's a fancy word for arguing — one of the stories in the Haggadah, the script for the Passover Seder, ends with the so-called "punchline" of four rabbis being interrupted in a heated discussion by their students telling them the sun has risen and it's time for breakfast...“The education, deliberation, and questioning inherent in the tradition of Jewish arguing and jurisprudence — these are unquestionably Jewish values. So is the commitment to social justice inherent in the obligation of tzedakah. No one would argue that these values are unique to Judaism. But their expression within Judaism is a big part of why they're so important in so many Jewish homes — and to many people who grow up in those homes.” [Source: Dara Lind, Vox, April 22, 2016]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2024