Home | Category: Judaism Beliefs / Jewish Sects and Religious Groups

MYSTICAL JUDAISM

Kabbalah Adam Tree Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai Driven is regarded as the founder of modern mystical Judaism. Driven into hiding by Romans in the A.D. second century, he developed a mystical philosophy that was passed from rabbi to student for more than a thousand years before it was codified into the “Zohar” (“Book of Divine Splendor”), the foundation of modern Jewish mysticism. Each year Hasidic Jewish pilgrims gather at Rabbi Simeon’s purported grave in the Galilee town of Meron for the holiday of Lag d'Omer, to mark Rabbi Simeon's survival of the Kokhba revolt that was crushed by the Romans in 132-35 A.D. The event is marked with bonfires and the first hair cuts for three year old boys.

Some trace Jewish mysticism back to ancient times. It may have its beginnings in the esoteric teachings and speculation of early sects such as the Essenes, of Dead Sea scroll fame, and was influenced in early Talmudic times by Gnosticism, a notion late regarded as heresy. Over time a special ecstatic kind of mysticism developed that taught followers ways and techniques of having visionary experiences but were not considered divine unions.

Early Jewish mystics described ascensions of the soul that were transcendent. The “numinous” aspects of God were expressed as rising through spheres,, worlds and heavens, escorted by angelic “guardians.” There was no reference to living communion which would become common later. Chants were sometimes part of the rituals and some of these have endured in prayers such as the “trisagion” (“Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts”).

Gershom Scholem, a nationalist German-Israeli, is widely regarded the most influential 20th century scholar on Jewish mysticism. Fluent in Hebrew, German and English and able to read Greek, Latin, Arabic and Aramaic, he is the author of “Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism” and the “Sabatai Sevi: The Mystical Messiah” .

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism; Encyclopædia Britannica, britannica.com/topic/Judaism; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Aish.com aish.com ; Jewish Museum London jewishmuseum.org.uk; Jewish History: Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Kabbala” by Ted Balestreri Amazon.com ;

“Sefer Yetzirah: The Book of Creation” by Aryeh Kaplan Amazon.com ;

“Kabbalah for Beginners: Understanding and Applying Kabbalistic History, Concepts, and Practices” by Brian Yosef Schachter-Brook Amazon.com ;

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com ;

“Judaism: History, Belief and Practice” by Dan Cohn-Sherbok Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

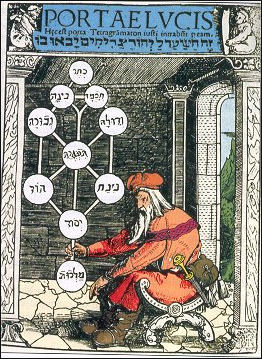

Medieval Mystical Judaism

The Jewish mystical movement matured in Spain in the 13th century and influenced future generations. These Jews hoped to commune with God using meditation, and spiritual exercises. Influential mystical books include the “Book of Creation, Book of the Pious “ and “Book of Divine Splendor” . The latter was complied by Rabbi Moses de Leon of Granada who described God’s mystical power in terms of “sefirot” (“the attributes of God”, also spelled sefirah, sephirot), represented by a seven-branched candlestick.

The Jewish mystical movement matured in Spain in the 13th century and influenced future generations. These Jews hoped to commune with God using meditation, and spiritual exercises. Influential mystical books include the “Book of Creation, Book of the Pious “ and “Book of Divine Splendor” . The latter was complied by Rabbi Moses de Leon of Granada who described God’s mystical power in terms of “sefirot” (“the attributes of God”, also spelled sefirah, sephirot), represented by a seven-branched candlestick.

Paul Mendes-Flohr wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: The first written evidence of Jewish mysticism was a collection of some 20 brief treatises originating from the Talmudic period (third century A.D.) and collectively known as Hekhalot ("Supernal Palaces") and Merkavah ("Divine Chariot") literature. The writings record a journey through the celestial palaces to the vision of God's chariot, or throne. In the second half of the twelfth century there emerged groups of scholars in the Germanic lands, known in Hebrew as Ashkenaz, who developed an acute mystical consciousness. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com

Writing under the trauma of the massacres of Jews during the Crusades, they reflected on the mystery of the inner life of God as a key to understanding what seemed to be his ambiguous relationship to history and Jewish fate. Most of the literature produced by this mystical school, known as Hasidei Ashkenaz (pious men of Ashkenaz), was either anonymous or pseudepigraphic. In addition to speculative theosophical literature, these scholars produced ethical tracts that sought to inculcate a severe pietistic discipline touching virtually every aspect of life. ]

Explaining the roots of Jewish mysticism Gershom Scholem wrote: “The thinking of the Jewish mystics provided a bond with certain impulses in the popular faith, fundamental impulses spring from the simple man’s fear of life and death, to which Jewish philosophy had no satisfactory response.”

Kabbalah

The Kabbalah is the name given to Jewish mystical knowledge passed down orally from generation to generation and hinted at in the Talmud. It is concerned with finding hidden meaning in the Scriptures, reaching elevated planes and ecstatic states, delving into magic, and speculating on the coming of the Messiah. Kabbalah has been compared to Sufism, Islamic mysticism. The word Kabbalah roughly means “esoteric tradition” and more precisely “what is receives,” a reference to Moses receiving the laws of God at Mt. Sinai, and a word widely used on modern Israel to describe the reception desk at hotels, among other things.

Kabbalah grew out of the mystical reading of the Scriptures that arose in France and Spain during the twelfth century, culminating with the composition in the late thirteenth century of the Zohar ("Book of Splendor"), which, especially as interpreted by Isaac Luria (1534–72), exercised a decisive influence on late medieval and early modern Jewish spiritual life.

Kabbalah is a complex system of mystical philosophy in which mysticism is only one phase. It explores a inward-seeking side of religion that contrasts markedly with the traditional, more outward-looking, community-rooted and law-driven Judaism. The goal is not to follow laws and rituals but rather to seek the divine within oneself. Its followers believe that understanding and mastering the Kabbalistic teachings will bring one closer to God and allow greater insight into God’s creation.

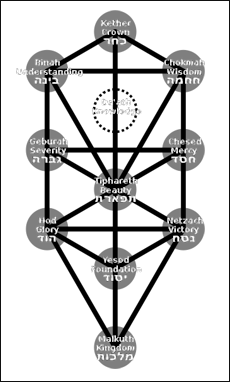

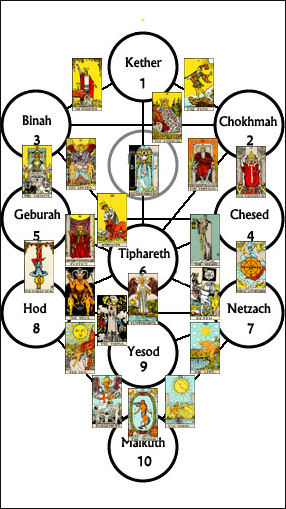

Medieval Tree of Life The religious scholar Eliezer Segal said: “The Jewish mystical doctrine known as "Kabbalah" (="Tradition") is distinguished by its theory of ten creative forces that intervene between the infinite, unknowable God ("Ein Sof") and our created world. Through these powers God created and rules the universe, and it is by influencing them that humans cause God to send to Earth forces of compassion (masculine, right side) or severe judgment (feminine, left side).”

At the heart of Kabbalah is a belief that God has a hidden, unknowable side and a self-revealing side that can be attained through religious experience. The form is so inaccessible and mystical that no words can describe it and no thoughts can comprehend it so there is no use in even trying. The latter is what concerns those interested in Kabbalah. Traditionally, it was only taught to pious Jewish men over the age of 40 who has spent a lifetime immersed in the study of Hebrew texts.

Kabbalah has such a long and twisted history that scholars say it is often better to think of several kabbalahs rather than just one. Concepts first raised by Kabbalists have infused their way into all aspects of modern Judaism. Joseph Dan of the University of Jerusalem wrote: “There is hardly a Jewish idea that cannot be described as “kabbalistic” with some justification.”

Book: “Kabbalah: A Very Short Introduction” by Joseph Dan (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Early History of Kabbalah

Despite claims that Kabbalah is a form of mystical teaching practiced by Moses it in fact has it origins in medieval Europe. In 13th century Spain and southern France, Jewish scholars claimed they possessed secret scriptural knowledge that had originated with Moses and had been passed down orally over the centuries. These scholars and exegetes, later known as kabbalists, were focused primarily on two sections of the Torah that were forbidden by the Talmud to be discussed publically. The first is the description of Creation in Genesis and the second is a description in the Book of Ezekial of Ezekial’s vison of a cosmic chariot. “The World of Emanations” , a complex organization consisting of ten hierarchically-arranged “sefirot” (variously described as potencies, emanations, arteries. potentialities or foci), was described in the 12th century (See Below). The Zohar, Kabbalah’s main text, was written in the 13th century.

Kabbalah emerged at a time when Judaism was dominated by rabbis who set rigid, detailed laws that all Jews were expected to follow unquestioningly. Judaism at that time was based in moral rationalism and included a code of ethics. It emphasized the primacy of charity and discredited esoteric beliefs and pursuing deep issues such as the meaning of God. Kabbalists sought not only to define and characterize God but also to tap into his spiritual and cosmological power, a pursuit regarded by purists as heretical.

Kabbalists first scrutinized non-Kabbalist Jewish texts and came up with elaborate and complex models of the cosmos based on interpretations of these texts. They described the kingdom of heaven and how humans could transcend their own being and “face God in his glory.”

Paul Mendes-Flohr wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: In neighboring France and Spain the seeds of a parallel school of Jewish mysticism, known as Kabbalah, were sown. Abraham ben David of Posquieres (c. 1125–98), in Provence, one of the most renowned rabbinical scholars of his age, was a fierce critic of Maimonides' attempt to reduce the Talmud to a code of law and to render Judaism a species of rational philosophy. Although a prolific writer, he limited his mystical teachings to oral instructions to his sons. They became the literary guides of the emerging Kabbalah movement, which purported to be based on an ancient tradition of esoteric readings of the Torah's deepest meanings.

These teachings were elaborated by Rabbi Moses ben Nahman (known as Nahmanides or the Ramban; 1194–1270) of Gerona. Deeply impressed by French rabbinical scholarship, he worked to raise the prestige and significance of Talmud study in Spain. He, too, objected to Maimonides' attempt to render philosophy the touchstone of religious truth. In his voluminous writings, some 50 of which are preserved, Nahmanides wove, particularly in his commentary on the Torah, his teachings in encoded form. Kabbalists of the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries devoted considerable effort to decode Nahmanides' teachings. As elaborated by his and Abraham ben David's disciples, Kabbalah spread throughout the Jewish world.

The Zohar

The Zohar appeared in Spain in 1280 and was written in Aramaic, a language the Jews had not used for centuries. More than 1,800 pages long and written by Moses de Leon, it explores divine mysteries under the guise of commentary on the Torah. It includes Chaucer-like tales about traveling sages, with more than 400 stories, numerology, erotic poetry, scriptural commentary and satire. Described as emanations that provided the foundation of Kabbalism, it is currently being translated into English by Stanford history professor Daniel Matt (the first two of 11 volumes were published in 2004)

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: The various mystical impulses of Kabbalah culminated in the appearance in the late thirteenth century of the Zohar ("Book of Splendor"), which became its main text. The principal author of this multivolume pseudepigraphic work was identified by twentieth-century scholars as Moses de Lion (c. 1240–1305) of Castile. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Written as a commentary on the Torah, the Zohar is presented as the esoteric Oral Torah taught by Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai, a tanna (teacher) of the fourth generation and one of the most prominent disciples of Rabbi Akiva and the teacher of Judah ha-Nasi, the editor of the Mishnah. Written in a symbolically rich Aramaic, the Zohar inspired numerous works that sought to develop further insights into the hidden layers of the Torah's meaning as the ground of the ultimate and most intimate knowledge of God.

The "Zohar" (or "Book of Splendour") is a treasure trove of Kabalistic teaching. Important books of the Zohar have been translated into English by S. L. MacGregor Mathers. The "Zohar" is the mainly concerned with the essential dignities of the Godhead, with the Emanations which have sprung therefrom, with the doctrine of the Sephiroth, the ideals of Macroprosopus and Microprosopus, and the doctrine of Re-incarnation.

Later History of Kabbalah

Kabbalah was the dominant form of Jewish piety in the 16th and 17th century, with the Zohar regarded as the third holiest text after the Torah and Talmud. The most influential Kabbalah movement, Lurianic Kabbalah, developed in Safed in Galilee in the 16th century. It was led by Rabbi Isaac Luria and was fueled by the Inquisitional persecution of Jews in Spain, which was viewed as another example of extreme persecution and compared with the destruction of the Second Temple in A.D. 70.

Kabbalah was the dominant form of Jewish piety in the 16th and 17th century, with the Zohar regarded as the third holiest text after the Torah and Talmud. The most influential Kabbalah movement, Lurianic Kabbalah, developed in Safed in Galilee in the 16th century. It was led by Rabbi Isaac Luria and was fueled by the Inquisitional persecution of Jews in Spain, which was viewed as another example of extreme persecution and compared with the destruction of the Second Temple in A.D. 70.

Paul Mendes-Flohr wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: The expulsion of the Jews from Spain and Portugal at the end of the fifteenth century engendered a profound sense of crisis and messianic longing. This was expressed through the speculations spawned by new schools of Kabbalah established in Greece, Italy, Turkey, and the Land of Israel. Presented as commentaries on the Zohar, these writings had the questions of evil and redemption as their central themes. In the sixteenth century the small town of Safed in Galilee became the center of this new, indeed revolutionary, trend in Kabbalah, which gained its fullest expression with Rabbi Isaac Luria (1534–72) and his disciples, especially Rabbi Hayyim Vital (1542–1620). Expounding a messianic theology based on motifs and images from the Zohar, Lurianic Kabbalah taught that the Exile and Israel's tragic history were but symbolic reflections of a higher reality in which part of God suffered exile, trapped in the material realm through a flaw in the process of creation. In fulfilling the precepts of the Torah with the proper mystical intent, the Jewish people redeemed both God and themselves. By virtue of this teaching, Kabbalah was transformed into a messianic myth that allowed the Jews to believe they could actively change the course of their history and at the same time cleanse the world of evil, which was a result of God's exile. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Kabbalah fell out of favor in the 18th century when other sects developed and ideas from the Enlightenment influenced Judaism. From that time forward it was dismissed as a medieval superstition. As Kabbalism was losing influence Hasidism was developing in eastern Europe and being embraced more by ordinary Jews. Many Kabbalist masters were killed in the Holocaust. Rabbi Kadouri, who died at the age of 106 in 2006, was one of the main figures of Kabbalah in the 20th century. His powers went beyond religion and spiritualism into politics. In 1999, a peace deal between Israel and Syria broke down after Rabbi Kadouri condemned it. In 2000, a little-known politician Moshe Katsav defeated Noble-prize-winner Shimon Perez in an election for Israel’s president after Kadouri said he had a “vision” that Katsav was favored by the heavens.

Madonna and Kabbalah Today

The pop singer Madonna is interested in Kabbalah and is a follower of the Jewish Kabbalah sage Rabbi Yehuda Ashlag. She began practicing Kabbalah in 1997 and made a highly publicized visit to Israel in 2004 and made a visit to Rabbi Ashlag’s grave at midnight. Other celebrities that have shown an interest in Kabbalah have been Demi Moore and Britney Spears. Madonna and Moore are linked the Los Angeles-based Kabbalah Center, which was opened in 1971 and downplays Kabbalah’s Jewish roots and emphasized its spirituality. Followers take expensive courses and wear red string to ward off the Evil Eye, a practice not linked to traditional Kabbalah study. Some swear by healing “Kabbalah water.” Purists scoff at the idea of non-Jews practicing Kabbalah.

Madonna doing "Vogue"

The town of Safed in Israel is regarded the mystical center of Kabbalah. It contains the tombs of important Kabbalah rabbis, including Rabbi Isaac Luria. In recent years is has become sometimes of a New Age capital of Israel, attracting more than its share Jewish and non-Jewish faddists and quasi spiritualists. One of the biggest draws is the Ascent Center.

One Chicago resident who attended a $66, four-day seminar to “get some energy” told AFP, “Kabbalah teachers you about the power you have inside you, how to control your inner instinct, how to make sense of emotions. Our generation seems to be searching for meaning, for goals and answers, there’s a lot in Kabbalah that speaks to people from different backgrounds. Now with technology, materialism, people have lost touch with their basic needs and desires.”

Kabbalah Beliefs

Followers of Kabbalah believe the accessible side of God is tied with his self-revelation as expressed in the early texts of the Bible. Kabbalists look beyond a superficial reading of passages from Genesis and other Biblical chapters and look for deeper divine meanings. The term “emanation” is used instead of “creation” to describe the revelation of the God’s being.

Kabbalists believe that before creation the universe was a chaotic place dominated by pleroma — omnipresent nothingness. Through the act of “tsimtsum” , self limitation, God forced the universe to contract in such a way that Creation could take place. During this process brilliant emanations of God (the “sediroth” described below) flowed outward. Kabbalists try to tap into these emanations.

Kabbalists believe that every human act has divine, mystical significance, that individual human actions can influence the divine order and bring about the tikkum, or redemption, a concept that is a cornerstone of ultra-Orthodox Judaism and is essential for an understanding of Jewish culture. . Kabbalists regard prayer as intense mystical meditation and an act of serving God. They also believe that being redeemed and achieving perfect order within oneself can lead to the salvation of the world.

Kabbalism is full of angels, demons and spirits that are not supposed to be worshiped or adored but addressed and exorcized with amulets and magic formulae. The concept of male and female union is important and often have erotic qualities to it. The 13th century Spanish Jewish scholar Moses de Leon said, “Without arousal below there is no arousal above.”

Ten Sefirot

Kabbalists believe that during Creation the “sefirot” flowed into vessels of the material worlds but these vessels were to fragile to contain forces of such power. The vessels broke apart and the sefirot scattered and the ideal process of Creation was thwarted and world has never been right since. “Tikkum” is regarded an effort to right this wrong and restore order in confusion by returning the sefirot to it proper places.

The ten “sefirot” are listed as 1) Primeval Will, 2) Wisdom, 3) Intuition, 4) Grace, 5) Judgement, 6) Compassion 7) Eternity, 8) Splendor, 9) All Fractfying Forces, and 10) “Shekhinah” (“the hidden radiance of the totality of the hidden divine life which dwells in every created and existing being”) They are related to one other in numerical, alphabetical, metaphorical and cosmological terms with two of them — most importantly the tenth force — being female.

The ten “sefirot” are listed as 1) Primeval Will, 2) Wisdom, 3) Intuition, 4) Grace, 5) Judgement, 6) Compassion 7) Eternity, 8) Splendor, 9) All Fractfying Forces, and 10) “Shekhinah” (“the hidden radiance of the totality of the hidden divine life which dwells in every created and existing being”) They are related to one other in numerical, alphabetical, metaphorical and cosmological terms with two of them — most importantly the tenth force — being female.

In many ways the six and tenth “sefirot” are regarded as the most important. They serve as the crux for the whole system and provide channels for higher and lower potencies to pass back and forth, helping to harmonize them. A number of male symbols, such as the King and Sun, are tied to the six “sefirot” while a number of female symbols such as the Moon and Queen are tied to the tenth “sefirot” and the relationship between the two has a lot erotic qualities. The central mystery of Kabbala is the “sacred marriage” between them and the greatest catastrophe would a divorce between them.

The goal of the Kabbalah practitioner is to maintain the male and female union within him or her. Sin is viewed as the disruption of this unity. The male-female is regarded as mystical and internal and is not part of man’s relation with God. Instead of a union with God, Kabbalists seek communion with God through a union of mystical forces with the individual serving as an analogy for the divine.

Jewish Kabbalist Mystical Practices

In a discussion of Jewish mystical practices. Professor Les Lancaster We must recognise that there are, in broad terms, two different ways of thinking. The first is normal, everyday rational thought - thinking about things you have to do, or about ideas, or about people around you. The second is, by comparison, less logical and less oriented to immediate everyday goals. This second is a more penetrating kind of thinking. [Source:Professor Les Lancaster, Liverpool John Moores University, BBC, August 13, 2009 ^]

“It involves shifting the centre of gravity of the mind away from the sense of 'I' which normally dominates our goals. Like all meditative practices, Jewish mystical techniques are directed towards enhancing this second form of thinking. At the same time, these practices cultivate an awareness of the divine presence in all things. ^

“In fact, the first type of thinking is simply a surface layer of thought. If you imagine the mind as a sea, then rational thought is simply the surface level of waves on the water. The major currents operate at the deeper levels of the ocean. The objective of meditation is to engage with these deeper currents. One of the major texts of Kabbalah, the 12th-century Bahir, writes that the biblical prophet Habakkuk 'understood God's thought.' It tells us: Just as human thought has no end, for even a mere mortal can think and descend to the end of the world, so too the ear also has no end and is not satiated. Jewish mystical practices enable us to use thought to 'descend to the end of the world', that is, to plumb the depths where mind and physical reality are no longer separate.” ^

Kabbalah, Madonna and Meditation

Kabbalah has traditionally only been taught to men who devoted their lives to studying Judaism. Britney Spears, Demi Moore and Madonna are followers of Kabbalah. Madonna described it as “very punk rock.”

Some regard some aspects of Kabbalah as being akin to meditation. A form of introspective contemplation, meditation is the act of relaxing and clearing the mind through balancing mental, physical, and emotional states, getting rid of all thoughts about the past and present and focusing on the present. This is done by shutting out the outside world and focusing within, often with the aid of sounds, words, images and/or breath.

According to H.A. Slagter of the University of Amsterdam: “Meditation is a process by which an individual controls his/her mind and induces a mode of consciousness either to achieve some benefits or for the mind to simply acknowledge is contents without being identified with the content, or just as an end in itself.” (Slagter, 2008).

See Meditation Under Yoga and Meditation factsanddetails.com

Jewish Kabbalist Meditation

Kabbalah Tree of Life Professor Les Lancaster wrote: “Within the overall framework of Judaism, meditative practices are intended to deepen the individual's engagement with all aspects of the religion. Meditation and techniques of concentration can: 1) heighten one's understanding of the Torah; 2) develop an understanding of ritual and other religious observances; 3) give direction to prayer; and 4) increase one's awareness of others' needs. More generally, Jewish meditation is understood as:

A) promoting a greater closeness to God; B) disciplining the mind, so that one has greater ability to focus mentally; C) bringing an awareness of those regions of the mind that had previously been 'unconscious'. [Source:Professor Les Lancaster, Liverpool John Moores University, BBC, August 13, 2009 ^]

One of the oldest texts that describes Jewish meditation practices is the Sefer Yetsirah: Consider the following extract:

Ten dimensions of nothingness. Their measure is ten to which there is no end.

A depth of beginning, a depth of end; a depth of good, a depth of evil; a depth of above, a depth of below; a depth of east, a depth of west; a depth of north, a depth of south.

The unified Master - God faithful King - rules over all of them, from His holy dwelling place, until eternity of eternities.

“The meditation based on this passage entails consciously building up a deep sense of your place in relation to the dimensions. We begin with 'depth of beginning'. You could ask yourself: what first triggered the situation in which you presently find yourself? As the mind arrives at answers (perhaps you are reading this because a friend thought you would be interested), continue by dismissing the idea that the answer might be definitive and final; there is always a further root (what is it about you that might have led the friend to think you would be interested; where did that quality in you develop from, and so on?). ^

“When you can no longer put the answer in words (perhaps some ineffable intimation of a root in your soul), begin to move forwards in time. What seem to be the likely consequences of your immediate situation? Again, continue to go beyond the immediate answers and stretch the bounds of your mental representations. In relation to the depth of good, the question to address concerns that which connects you to the larger whole - to God. And, for evil, what leads to a sense of disconnection? Always, you must stretch the bounds of the answers which pop into the mind. The meditation continues with the first of the six directions of space. What is immediately above you? Air... the ceiling... other rooms... the roof... birds... sky... vastness of space... the infinite that cannot be formed in the mind... ^

“It is as if you generate a beam of light from within that is gradually extended further and further whilst, at the same time, maintaining your awareness of the centre, the heart as the source of light... And then continue into the remaining directions. You may glimpse your inner core suspended at the heart of a web of infinite interconnections. Ultimately, the objective is for you to experience a sense of meaning that can only be described as witnessing your self as a centre within a network of interconnections which plunge into an infinite nothingness.” ^

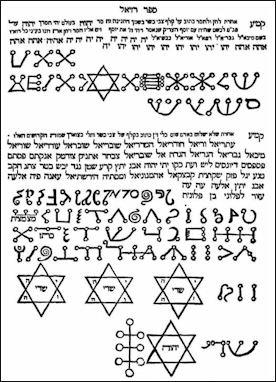

Visualising the Hebrew Letters in Jewish Kabbalist Meditation

Professor Les Lancaster wrote: “Most Jewish meditations require at least a basic knowledge of Hebrew, the sacred language of Judaism. Jewish mystics view the Hebrew letters as the agents of creation. There are many techniques for visualising and working with the letters. The Sefer Yetsirah states that God engraved the letters, carved them, weighed them, permuted them, combined them, and formed with them all that was formed and all that would be formed in the future. Each of these processes is mirrored in a kabbalistic practice of visualisation.” [Source: Professor Les Lancaster, Liverpool John Moores University, BBC, August 13, 2009 ^]

Professor Les Lancaster wrote: “Most Jewish meditations require at least a basic knowledge of Hebrew, the sacred language of Judaism. Jewish mystics view the Hebrew letters as the agents of creation. There are many techniques for visualising and working with the letters. The Sefer Yetsirah states that God engraved the letters, carved them, weighed them, permuted them, combined them, and formed with them all that was formed and all that would be formed in the future. Each of these processes is mirrored in a kabbalistic practice of visualisation.” [Source: Professor Les Lancaster, Liverpool John Moores University, BBC, August 13, 2009 ^]

“Preparation for visualisation requires closing or half-closing the eyes. Normally, when you close the eyes you automatically turn the visual sense off inwardly as well. For this kind of a practice, however, you must remain acutely aware of the visual sense even whilst being closed to outward seeing. It is as if you are seeing the screen made by the insides of your eyelids. Engraving means outlining the letter in the mind's eye; as the outline is built up, you must hold a clear intent to operate with a specific letter. Carving entails establishing the letter as a powerful presence in visual consciousness; energy is focused on the letter until it blazes like fire on the inner screen of the mind.^

“The intent behind weighing is that of allowing the letter's qualities to impress themselves upon you; a receptive state must be cultivated, in which you might, for example, find meaning in the letter's shape, its constituent parts, its relations with other letters, and so on. This is followed by permuting the letter with other letters; maybe, having focused on the letter's constituent lines, other letters using those lines arise in the mind. ^

“Letters are then combined, enabling them to enter into relationships one with another. The final stage concerns the meaning of those combinations; what kind of a presence is formed when those specific letters come together? It is not simply a matter of knowing the word (and, in fact, not all combinations produce words), but rather you should attempt to discern the nature of the entity depicted by the specific combination of letters. What tensions arise between the letters, or do they share a more harmonious relation? ^

“Another meditation with the Hebrew letters introduces their sounds, as indicated in the following audio extract. These kinds of practice open up regions of meaning that extend beyond the reach of the everyday rational mind. As quoted earlier from the Bahir, they begin the process of forging deep links with 'God's thought'. ^

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, Library of Congress, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024