Home | Category: Muslims and Arabic / Arabs and Arabic

ARABIC

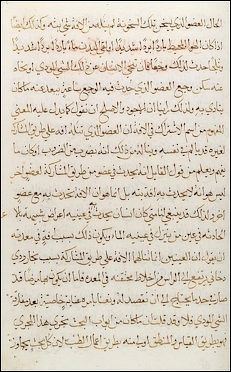

"Al-A 'da' al-alma, an Arabic text in naskh script

Arabic is the dominant language throughout North Africa and the Middle East. It is a Semitic language, like Hebrew, the language of the Jews. The Semitic languages are part of the Afro-Asiatic family of languages. Other Semitic languages still spoken today include Maltese, Aramaic (the language of Jesus, still spoken in parts of Syria, Lebanon and Iraq) and Amharic, and other languages of Ethiopia such as Harari and Tigre.

Arabic is the fifth or sixth most widely spoken language in the world based on native speakers. Figures vary depending on the source and how the language speakers are defined. About 280 million people speak it. Most of those who speak it fluently as their first language are in North Africa and Middle East. It is an official language in 26 countries. Only French and English score higher in this repsect. Arabic contains many words from different languages, for example Turkish, Hebrew, Persian and others.

Only 20 percent of Muslims speak Arabic as their first language. Illiteracy rates are high in the Muslim world. Many non-Arab students who study the Qur’an in Arabic have little idea what they are memorizing.

Even so, the Arabic language is one of the unifying forces of the Arabic people. Spoken Arabic varies greatly from region to region but classical Arabic, the language of the Qur’an, has remained largely unchanged since the 7th century. Arabic dialects are so different that some linguists argue that Arabic is not a single language but a family of languages as different from each other as Spanish, Portuguese, French and other Romance languages are. The main dialect, Egyptian Arabic, is spoken by tens of millions of people.

Arabic is the language of the Qur’an, the lingua franca of people in the Muslim world, and is understood by people in places as diverse as Mali, Uzbekistan and Indonesia. Arabic is ideal for storytelling and poetry becuase it is full of images, metaphorical potential and multilayered meanings. Because of its association with the Qur’an, Arabic has deeply influenced the languages of all Muslims. Non-Arab Muslims that speak it and read it well are regarded as especially pious.

The twelve most widely spoken languages are (number of speakers): 1) Mandarin Chinese (975,000,000); 2) English (478,000,000); 3) Hindi (437,000,000); 4) Spanish (392,000,000); 5) Russian (284,000,000); 6) Arabic (225,000,000); 7) Bengali (200,000,000); 7) Portuguese (184,000,000); 9) Malay-Indonesian (159,000,000); 10) Japanese (128,000,000); 11) French (125,000,000); 12) German (123,000,000).

Arabs: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Who Is an Arab? africa.upenn.edu ; Encyclopædia Britannica article britannica.com ; Arab Cultural Awareness fas.org/irp/agency/army ; Arab Cultural Center arabculturalcenter.org ; 'Face' Among the Arabs, CIA cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence ; Arab American Institute aaiusa.org/arts-and-culture ; Introduction to the Arabic Language al-bab.com/arabic-language ; Wikipedia article on the Arabic language Wikipedia

History of Arabic

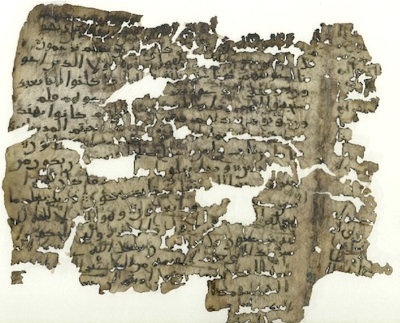

7th century Qur'anic manuscript in Mekkan script

The first evidence of the Arabic as a spoken language is from accounts of wars in 853 B.C. Arabic was once labeled a Semitic-Hamitic language after Shem and Ham, whose descendants reportedly started their receptive languages after the Biblical Tower of Babel incident. Arabic is believed to have begun as an isolated tongue of Bedouins living on the Arabian peninsula. It became the language of the Qur’an during Muhammad’s lifetime and was spread with Islam around the Middle East, North Africa and parts of Asia in the 7th century. It replaced many languages and has coexisted with languages such as Latin, Latin, Turkish, Hindi, Persian, Malay and host of other languages.

Arabic is said to have been "uncreated" like the Qur’an. Adam is said to have inscribed the language on tablets of clay, and today it is the written and spoken language of Islam, whether the faithful are in Indonesia, Pakistan, Turkey, Senegal or Yemen. In the early years of Islam, Arabic was a widely-used, high-status language.

In North Africa, Arabic was introduced to the coastal regions by the Arab conquerors of the seventh and eighth centuries A.D. Arabic language and culture had an even greater impact under the influence of the beduin Arabs, who arrived in greater numbers from the eleventh century onward. [Source: Helen Chapan Metz, ed. Algeria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1994]

Many Arabic place named remain in southern Europe, especially in Sicily and Spain, which was occupied by the Arabs. Between the 9th and 15th centuries, Arabic was such an important language in science and medicine that scholars in northern Europe often had to learn it along with Latin and Greek.

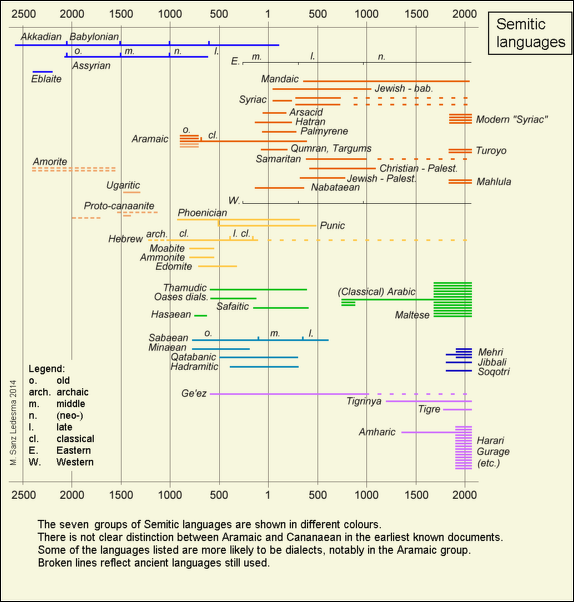

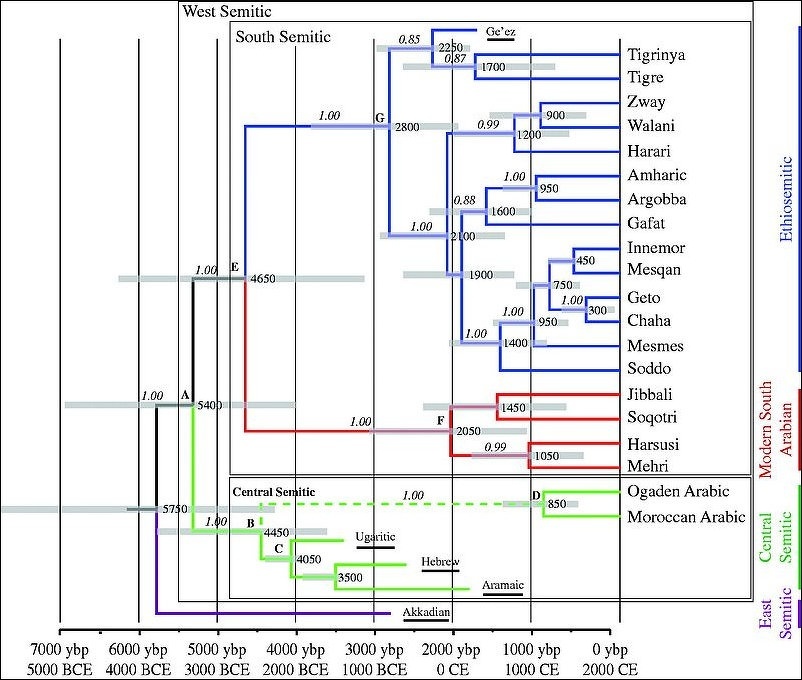

Semitic Languages

David Testen wrote in the Encyclopædia Britannica: “Semitic languages, languages that form a branch of the Afro-Asiatic language phylum. Members of the Semitic group are spread throughout North Africa and Southwest Asia and have played preeminent roles in the linguistic and cultural landscape of the Middle East for more than 4,000 years. [Source: David Testen, Encyclopædia Britannica]

In the early 21st century the most important Semitic language, in terms of the number of speakers, was Arabic. Standard Arabic is spoken as a first language by more than 200 million people living in a broad area stretching from the Atlantic coast of northern Africa to western Iran; an additional 250 million people in the region speak Standard Arabic as a secondary language. Most of the written and broadcast communication in the Arab world is conducted in this uniform literary language, alongside which numerous local Arabic dialects, often differing profoundly from one another, are used for purposes of day-to-day communication.

Maltese, which originated as one such dialect, is the national language of Malta and has some 370,000 speakers. As a result of the revival of Hebrew in the 19th century and the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, some 6 to 7 million individuals now speak Modern Hebrew. Many of the numerous languages of Ethiopia are Semitic, including Amharic (with some 17 million speakers) and, in the north, Tigrinya (some 5.8 million speakers) and Tigré (more than 1 million speakers). A Western Aramaic dialect is still spoken in the vicinity of Maʿlūlā, Syria, and Eastern Aramaic survives in the form of uroyo (native to an area in eastern Turkey), Modern Mandaic (in western Iran), and the Neo-Syriac or Assyrian dialects (in Iraq, Turkey, and Iran). The Modern South Arabian languages Mehri, arsusi, Hobyot, Jibbali (also known as Ś eri), and Socotri exist alongside Arabic on the southern coast of the Arabian Peninsula and adjacent islands.

Members of the Semitic language family are employed as official administrative languages in a number of states throughout the Middle East and the adjacent areas. Arabic is the official language of Algeria (with Tamazight), Bahrain, Chad (with French), Djibouti (with French), Egypt, Iraq (with Kurdish), Israel (with Hebrew), Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania (where Arabic, Fula [Fulani], Soninke, and Wolof have the status of national languages), Morocco, Oman, the Palestinian Authority, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia (with Somali), Sudan (with English), Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Other Semitic languages designated as official are Hebrew (with Arabic) in Israel and Maltese in Malta (with English). In Ethiopia, which recognizes all locally spoken languages equally, Amharic is the “working language” of the government.

Semitic language tree

Despite the fact that they are no longer regularly spoken, several Semitic languages retain great significance because of the roles that they play in the expression of religious culture—Biblical Hebrew in Judaism, Geʿez in Ethiopian Christianity, and Syriac in Chaldean and Nestorian Christianity. In addition to the important position that it occupies in Arabic-speaking societies, literary Arabic exerts a major influence throughout the world as the medium of Islamic religion and civilization.

Semitic Languages of the Past

David Testen wrote in the Encyclopædia Britannica: “Written records documenting languages belonging to the Semitic family reach back to the middle of the 3rd millennium bce. Evidence of Old Akkadian is found in the Sumerian literary tradition. By the early 2nd millennium bce, Akkadian dialects in Babylonia and Assyria had acquired the cuneiform writing system used by the Sumerians, causing Akkadian to become the chief language of Mesopotamia. The discovery of the ancient city of Ebla (modern Tall Mardīkh, Syria) led to the unearthing of archives written in Eblaite that date from the middle of the 3rd millennium bce. [Source: David Testen, Encyclopædia Britannica]

Personal names from this early period, preserved in cuneiform records, provide an indirect picture of the western Semitic language Amorite. Although the Proto-Byblian and Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions still await a satisfactory decipherment, they too suggest the presence of Semitic languages in early 2nd-millennium Syro-Palestine. During its heyday from the 15th through the 13th century bce, the important coastal city of Ugarit (modern Raʾs Shamra, Syria) left numerous records in Ugaritic. The Egyptian diplomatic archives found at Tell el-Amarna have also proved to be an important source of information on the linguistic development of the area in the late 2nd millennium bce. Though written in Akkadian, those tablets contain aberrant forms that reflect the languages native to the areas in which they were composed.

From the end of the 2nd millennium bce, languages of the Canaanite group began to leave records in Syro-Palestine. Inscriptions using the Phoenician alphabet (from which the modern European alphabets were ultimately to descend) appeared throughout the Mediterranean area as Phoenician commerce flourished; Punic, the form of the Phoenician language used in the important North African colony of Carthage, remained in use until the 3rd century ce. The best known of the ancient Canaanite languages, Classical Hebrew, is familiar chiefly through the scriptures and religious writings of ancient Judaism. Although as a spoken language Hebrew gave way to Aramaic, it remained an important vehicle for Jewish religious traditions and scholarship. A modern form of Hebrew developed as a spoken language during the Jewish national revival of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Semitic language chronology

Arabic Forms and Dialects

Arabic has developed into two main forms: 1) Classical Arabic, the religious and literary language, which is widely spoken and written throughout the Arab world and serves as a bond among all literate Muslims; and 2)colloquial Arabic, an informal spoken language, which varies a great deal from region to region. A standardized for form of colloquial Arabic is called Modern Standard Arabic, Both classical and colloquial forms coexist today. The Arabic spoken in Yemen mostly closely resembles the Arabic in the Qur’an.

According to Omniglot: “Classical Arabic — the language of the Qur'an and classical literature — differs from Modern Standard Arabic mainly in style and vocabulary, some of which is archaic. All Muslims are expected to recite the Qur'an in the original language, however many rely on translations in order to understand the text. Modern Standard Arabic — the universal language of the Arabic-speaking world — is understood by all Arabic speakers. It is the language of the vast majority of written material and of formal TV shows, lectures, etc. Each Arabic speaking country or region also has its own variety of colloquial spoken Arabic. These colloquial varieties of Arabic appear in written form in some poetry, cartoons and comics, plays and personal letters. There are also translations of the bible into most varieties of colloquial Arabic.

Arabic speakers are found in Afghanistan, Algeria, Bahrain, Chad, Cyprus, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kenya, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Oman, Palestinian West Bank & Gaza, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Tunisia, Turkey, UAE, Uzbekistan and Yemen. [Source: Omniglot

There are over 30 different varieties of colloquial Arabic. They include: 1) Egyptian - spoken by about 50 million people in Egypt and perhaps the most widely understood variety, thanks to the popularity of Egyptian-made films and TV shows; 2) Algerian - spoken by about 22 million people in Algeria; 3) Moroccan/Maghrebi - spoken in Morocco by about 19.5 million people; 4) Sudanese - spoken in Sudan by about 19 million people; 5) Saidi - spoken by about 19 million people in Egypt; 6) North Levantine - spoken in Lebanon and Syria by about 15 million people; 7) Mesopotamian - spoken by about 14 million people in Iraq, Iran and Syria; and 8) Najdi - spoken in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Jordan and Syria by about 10 million people [Source: ethnologue.com]

Semitic language genealogy

Arabic Grammar and Pronunciation

Arabic has been described as elegant and elaborate. It is filled with homographs (words with the same spelling but different pronunciations) and has relatively few sound patterns. There are no infinitives and no words for "have" or "be." Verbs have masculine and feminine forms and a different "you" is used depending on the sex of the person you are addressing. Numbers after 10 are considered singular and some noun plurals are shorter than their singular forms.

In Arabic, words with a dozen or so meaning can run on in long, unpunctuated sentences. Arabic words often consist of a root with three consonants and shifting vowels that carry auxiliary meanings. For example the word with the general meaning "killing" is K-T-L. Added vowels change the meaning. “Katala” is "he sought to kill:" “ aktala” is "he accused to kill;" “ katil” is "murder;" and “ kitl” is "enemy."

Arabic pronunciation is characterized by aspirations, and like Hebrew, is full of guttural sounds. A breathy, aspirated “H” causes the Adams apple it vibrate and is difficult for Westerners to pronounce. A letter called the “ayn” is equally difficult to pronounce. It resembles the sound of a throat-clearing hack and is often written as a "q" even though it sounds more like a "g." The country Qatar, for example, is pronounced like someone hacking and saying "Gatta."

Arabic: Devilishly Difficult to Learn

Sam Dillon wrote in New York Times: “For Americans, Arabic is a difficult language. It has some unfamiliar throaty sounds, a vast and ancient vocabulary, script that reads from right to left and dialects so distinct that native speakers from Morocco, Yemen and Iraq often cannot understand one another...The Foreign Service Institute at the State Department puts Arabic in its ''super-hard'' category, along with Chinese, Japanese and Korean, said James E. Bernhardt, chairman of the institute's department of Arabic and Asian languages. The institute estimates that bright students need at least 88 weeks of full-time training to reach entry-level professional proficiency, he said. By comparison, to achieve the same proficiency in Hebrew, which the institute rates as ''hard,'' requires 44 weeks, Mr. Bernhardt said. [Source: Sam Dillon, New York Times, November 16, 2003]

Jennifer Bremer wrote in the Washington Post: “What makes Arabic such a hard language for an English speaker to learn? The first challenge is the alphabet, in which a dot can transform an "n" into a "t" or an "h" into a "g." Second, because Arabic shares few words with English, a student starts from scratch to build up a working vocabulary. Arabic grammar is downright complicated as well, and very different from English in basic issues like word order. [Source:Jennifer Bremer, Washington Post, October 16, 2005 ***]

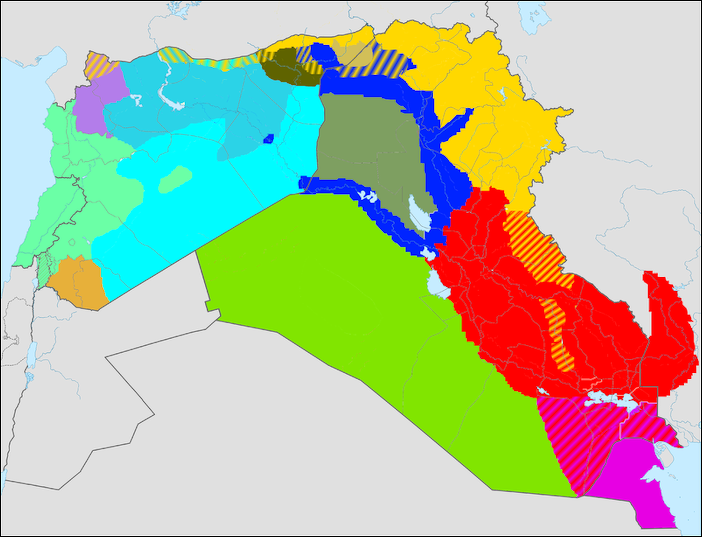

Iraqi and Syrian Arabic daielects: 1) Badawi: (green): 2) Badawi (incl. Najdi, dark olive green); 3) Badawi in Northern Iraq (beige); 4) Shammar and Tayy (dark brown); 5) Baggara (light blue); 6) South Shawi (blackish blue); 7) North Shawi Levantine (purple): 8) North Levantine (blue); 9) Central Levantine (brown); 10) South Levantine (Haurani, dark blue); Other: 11) North Mesopotamian (qəltu) 12) Iraqi (gilit, red); 13) Kurdish (gold); 14) Gulf Arabic (bright purple)

Robert Lane Greene wrote in Slate.com: “Learning Arabic is complicated. The first challenge, the script, is a tough one. But it is by no means the biggest. Arabic has an alphabet, so it's easier than, say, Chinese, which has a set of thousands of characters. There are just 28 letters, and it does not take long to get used to writing and reading right-to-left. (Though it still feels odd to open my book from what seems like the back.) Most of the letters have four different forms, depending on whether they stand alone or come at the beginning, middle, or end of a word. Even then, so far so good. But in Arabic, as in Hebrew, people don't include most vowels when writing. Maktab, or "office," is just written mktb. Vowels are included as little marks above and below in beginning textbooks, but you soon have to get used to doing without them. Whn y knw th lngg wll ths s nt tht hrd. But when you're struggling with comprehension to begin with, it's pretty formidable. [Source: Robert Lane Greene, Slate.com, June 9 2005 \~]

“Then there are the sounds those letters represent. I do not recommend chewing gum in Arabic class, because a host of noises articulated in the back of the throat makes it likely that the gum will end up in your lungs. Arabic has one "h" akin to ours, and another that has been described as the sound you would make trying to blow out a candle with air from your throat. That's not to be confused with another sound, the fricative kh familiar to German-speakers as the sound in "Bach." There's also 'ayn, a "voiced pharyngeal fricative," which is like the first sound in the hip-hop "a'ight." Unwritten in Roman-alphabet transliterations, it's actually a consonant that begins many common words and names, including "Arab," "Iraq," and "Arafat."

“The sounds are tough, but the words are tougher. An English-speaking student learning a European language will run across many familiar-looking words, but English-speaking Arabic students are not so lucky. Merav, an Israeli classmate, should have a leg up on us: Arabic and Hebrew both use a nifty, three-letter root system for word building. The three-letter root represents a general area of meaning, and different prefixes, vowel additions, and suffixes can make it into a person engaged in that activity, the place where it goes on, the general concept, and so on. Most famous is slm, which generally means "peace." Salaam is the noun for "peace," Islam is "surrender," and a Muslim is "one who surrenders." (In Hebrew, this can be seen in shalom.) Ktb functions similarly for writing: Kitaab is "book," kaatib is "writer," maktaba is "library." The State Department reckons that it takes 80 to 88 weeks (roughly a year in the classroom full-time and a year in-country) to get to a level 3 on a 5-point scale in Modern Standard Arabic, the language I am learning.

Arabic’s Special Challenge: MSA Verus Colloquial Arabic

Jennifer Bremer wrote in the Washington Post: “Unlike most languages, Arabic has two, very different, versions. Arabs use one language for writing and other formal purposes and another for day-to-day conversation. The formal language, usually called Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), is a streamlined version of the classical language, elegant and expressive, but hard to learn. The commonly spoken language (colloquial, or aamiya) uses different grammar, even different vocabulary from MSA. "How are you?" in MSA, for example, is " Kayf halak?" In Egyptian colloquial, it's " Izzayak?" [Source:Jennifer Bremer, Washington Post, October 16, 2005 ***]

Arab and Berber dialects in northern Algeria

“Colloquial Arabic is much easier to learn than MSA. It lacks MSA's grammatical niceties. In MSA, for example, nouns take case endings, as in Latin or German; colloquial doesn't bother with such folderol. Colloquial is often taught using familiar English letters instead of Arabic script — why bother with all those troublesome dots when colloquial is rarely written down, anyway? ***

“Despite colloquial's user-friendliness, most language programs in the United States (including those at the State Department) teach Modern Standard. This choice does not reflect linguistic elitism, at least not entirely. MSA has both advantages and disadvantages. On the plus side, it remains constant from Morocco to Iraq. All educated Arabs can speak and understand MSA, although native speakers would usually rely on colloquial outside of a formal setting such as a lecture hall or courtroom. ***

“MSA is widely used in diplomatic settings, even among Arabs. An Egyptian and a Moroccan or an Iraqi speaking together might well choose MSA because their respective colloquial languages are very different. Where an Egyptian would ask how you are with "Izzayak?" an Iraqi would say "Shlonek?" MSA's close association with classical Arabic keeps it from straying too far from the elegant 7th-century language of the Holy Qur’an. Colloquial dialects, conversely, have mixed and mingled freely with local and Western languages. To an Egyptian, potato is butatis , but to an Iraqi, it's puteeta. ***

“The written/spoken difference helps to explain the relatively high illiteracy rates in the Arab world, especially in rural areas with less exposure to formal speech. In rural Algeria, illiteracy tops 50 percent for men and 85 percent for women. In effect, students must learn to read in a foreign language, as different from their own as Chaucer is from today's English.” ***

Robert Lane Greene wrote in Slate.com: “MSA has about the same role in the Arab world that Latin had in medieval Europe: It's the language of writing, religion, and formal speeches, but it is no one's native spoken language any more. Arabic has long since become a series of "dialects," which are actually more like separate languages, as many varieties are mutually incomprehensible. Arabic spoken in Morocco is as different from Arabic spoken in Egypt and from Modern Standard as French is from Spanish and Latin. When Arabs from different regions talk to each other, they improvise a mix of Egyptian Arabic (which is understood widely because of Egypt's movie industry), Modern Standard, and a bit of their own dialects. [Source: Robert Lane Greene, Slate.com, June 9 2005 \~]

“So, if I go to Egypt or Lebanon in a year, having managed to get some near grip on my classroom language, I will be walking down the street asking people for a bite to eat in something that will sound almost as conversationally inappropriate to them as Shakespearean English would to us. Most literate Arabs know the Modern Standard from schooling, newspapers, television, sermons, and the like, though, so hopefully they will not laugh too hard as they help me out and respond in something I can almost understand. And that is if I work my tail off for the next year. Insha'allah.” \~\

Written Arabic

First Surah of the Koran

Arabic is written with a flowing Arabic script read from top to bottom and right to left (as opposed to left to right like English). According to one joke Arabic is read right to left rather left to right because of a mix up: those martyred expecting 72 virgins upon their arrival to heaven were presented with one 27-year-old virgin. Numerals are written from left to right. Arabic has also been written with the Hebrew, Syriac and Latin scripts. In turn it has been used write languages without scripts in Central Asia and other places.

Written Arabic is psychologically and sociologically important as the vehicle of Islam and Arab culture and as the link with other Arab countries. Two forms are used: the classical Arabic of the Quran and dialectical Arabic. Classical Arabic is the essential base of written Arabic and formal speech throughout the Arab world. It is the vehicle of a vast religious, scientific, historical, and literary heritage. Arabic scholars or individuals with a good classical education from any country can converse with one another. [Source: Helen Chapan Metz, ed. Algeria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

The ancient script of South Arabia influenced Ethiopia. Hebrew and Arabic evolved from Aramaic. Other languages written that are or have been written with Arabic script: Persian/Farsi, Pashto, Turkish, Urdu, Uyghur, Bosnian, Uzbek, Punjabi, Malay, Adamaua Fulfulde, Afrikaans, Arabic (Algerian), Arabic (Egyptian), Arabic (Lebanese), Arabic (Modern Standard), Arabic (Moroccan), Arabic (Syrian), Arabic (Tunisian), Arwi, Äynu, Azeri, Balti, Baluchi, Beja, Brahui, Chagatai, Chechen, Comorian, Crimean Tatar, Dari, Domari, Gilaki, Hausa, Hazaragi, Kabyle, Karakalpak, Konkani, Kashmiri, Kazakh, Khowar, Khorasani Turkic, Kurdish, Kyrgyz, Luri, Marwari, Mandekan, Mazandarani, Morisco, Palula,, Qashqai, Rajasthani, Rohingya, Salar, Saraiki, Serer, Shabaki, Shina, Shughni, Sindhi, Somali, Tatar, Tausūg, Wakhi, Wolof

Writing Written Arabic

The Arabic that people read and write are often very different from the Arabic they speak. In classical Arabic as in other Semitic scripts, only the consonants are written; vowel signs and other diacritical marks to aid in pronunciation are employed occasionally in printed texts. The script is cursive, lending itself to use as decoration.*

7th century Qur'anic manuscript in Hijazi script

The current Arabic alphabet consists of 28 letters that are made from 17 basic forms that consist of simple vertical and horizontal strokes. All the letters are basically consonants. Vowels are indicated by marks above and below the letters. These marks are usually omitted except in school textbooks and the Qur’an.

The Arabic writing system is called abjad. There are 28 letters. Some additional letters are used in Arabic when writing placenames or foreign words containing sounds which do not occur in Standard Arabic, such as “p” or “g”. Additional letters are used when writing other languages.

According to Omniglot: “Most letters change form depending on whether they appear at the beginning, middle or end of a word, or on their own. Letters that can be joined are always joined in both hand-written and printed Arabic. The only exceptions to this rule are crossword puzzles and signs in which the script is written vertically. The long vowels “a”, “i” and “u” are represented by the letters 'alif, yā' and wāw respectively. Vowel diacritics, which are used to mark short vowels, and other special symbols appear only in the Qur'an. They are also used, though with less consistency, in other religious texts, in classical poetry, in books for children and foreign learners, and occasionally in complex texts to avoid ambiguity. Sometimes the diacritics are used for decorative purposes in book titles, letterheads, nameplates, etc.

History of Written Arabic

Written Arabic is believed to have been influenced by the Phoenician alphabet, which also provided the basis for Hebrew, Greek and Latin alphabets, and the language of the Nabataeans, the inhabitants of Petra. Arabic script has been used to write Persian, Ottoman Turkish, Urdu and a host of other languages.

According to Omniglot: “The Arabic script evolved from the Nabataean Aramaic script. It has been used since the 4th century AD, but the earliest document, an inscription in Arabic, Syriac and Greek, dates from 512 AD. The Aramaic language has fewer consonants than Arabic, so during the 7th century new Arabic letters were created by adding dots to existing letters in order to avoid ambiguities. Further diacritics indicating short vowels were introduced, but are only generally used to ensure the Qur'an was read aloud without mistakes.”

page from 8th century "Uthman Qur'an" in Kufic script

In the early days of Islam, Arabic was written in two scripts in the Muslim period: “Naskhi” , the everyday cursive form, and “ Kufic” , a decorative, rectangular form named after the Iraqi city of Kufa and was commonly used in calligraphy.

Arabic Language and Class

"The poor man's Arabic is not the same as that of the elite, who speak an idiom that the illiterate, and semi-literate, underclass often does not understand," wrote Chris Hedges in the New York Times. "The forms of Arabic range from classical to colloquial; speaking one or the other quickly identifies an Arab by class and by level of education.”

When educated people from different Arabic countries meet, they converse in classical Arabic. Hedges wrote: "And, since enormous social and economic gulfs have been allowed to grow, language itself has become a barrier to understanding. The poor often cannot grasp the subtle rationalizations put forward by the educated. And the elite, isolated and besieged, are perplexed by the string of slogans and rote scriptural quotations, which they dismiss as incoherent babble even as they fail to comprehend the anger beneath."

"It is not easy to find parallels for this in the highly educated and more egalitarian societies of the West," Hedges asserts, "but consider this: What if 80 or 90 percent of American's spoke every day in the brutal and angry cadences of gangsta rap, while the members of a feudal upper class mused over their own demise in Elizabethan English."

Qur’an, Arabic, and Translations

Arabic is believed to be "uncreated" like the Qur’an. Adam is said to have inscribed the language on tablets of clay, and today it is the written and spoken language of Islam, whether the faithful are in Indonesia, Pakistan, Turkey, Senegal or Yemen. Many non-Arabs who recite Muslim prayers in Arabic have no idea what the prayers mean.

Muslims believe that the Qur’an is Arabic composition in its most perfect form. The Arabic spoken in Yemen mostly closely resembles the Arabic in the Qur’an. Qur’an passages often have red marks that indicate how people should breath when they recite it. Each aya , or verse is indicated by a gilded rosette at the end.

Qur'an

Because the Qur’an is regarded as the as the word of God, all translations are regarded as profanation. The Qur’an states quite unequivocally: “We have sent messenger save with the tongue of his people." The Qur’an is supposed to paraphrased or interpreted. The divines nature of Qur’an scripture is also why calligraphy is so important.

Translations are viewed not as embodiment of the true Qur’an but rather as guides to study. The first copies of the Qur’an translated into English were called The Meaning of the Glorius Qur'an . But despite these reservations the Qur’an has been translated: more than 20 English-language translations are available, most of which are a literal as possible. The Book and the Qur’an by Muhammad Shahrur, which tried to interpret the Qur’an for readers was widely banned in the Muslim world, despite it pious tone and popularity.

According to the BBC: “It was not until 1734 that a translation was made into English, but was littered with mistakes. Copies of the holy text were issued to British Indian soldiers fighting in the First World War. On 6 October 1930, words from the Qur’an were broadcast on British radio for the first time, in a BBC programme called The Sphinx."

Arabic Swear Words and Expressions

Mountain Dew in Arabic

Arabic Swear word — English Translation: Airi Fe Sabahak: My dick on your forehead; Neek rasi: Fuck my skull; Yla'an haramak: Damn your spouse; Kos okht ile nafadak: Fuck he who brought you to this life; Aire fe mabda'ak: My dick in your principles; Toj koo' mas: Come suck my penis; Zobree akbar minak: My dick is longer than you; Ya manache'h: Fag, gay; Air il'e yoshmotak: May you be struck by a dick; Air il'e yeba'atak: May you be stabbed by a dick; Fatah: Foreskin (considered a grave insult); Ah dena mukk: Damn your mother's religion; Ahhlass: Shut up; Koos: Cunt, pussy; Yebnen kelp: Son of a dog; Nikomak: Fuck your mother; Sharmoota (or Sharmuta): Whore, bitch; Gahba: Whore, bitch; Shlicke: Slut; Ahbe: Slut; Zarba: Shit; Khara: Shit; Kis: Vagina;

Elif air ab tizak: A thousand dicks in your ass; Elif air ab dinikh: A thousand dicks in your religion; Kisich: Pussy; Mos zibbi: Suck my dick; Waj ab zibik: An infection to your dick; Kelbeh: Bitch; Kul khara: Eat shit; Kanith: Fucker; Kwanii: Faggot; Ya Khawal: Faggot; Bouse Tizi: Kiss my ass; Ebn el metnakah: Son of a motherfucker; Inti sharmoota: You're a whore; Inta sharmoot: You're a male whore; Inta humar: You are a donkey (idiot: to a man); Inti humara: You are a donkey (idiot: to a woman); Inta shaz: You are a pervert; Gildak khashina awee: Your skin is very rough; Ikla hudumak: Take off your clothes; Aiyz temus?: Would you like a blow job?; Takhi: Bend over; Mus zibii: Suck my cock; Boos zibbi: Kiss my cock; Teazak: Ass; Kara: Ass; Teez: Ass; Zubrak: Penis, Cock, Dick; Mekyad: Penis, Cock, Dick; Ayir: Penis, Cock, Dick; Zibbi: Penis, Cock, Dick; Zib: Penis, Cock, Dick; Zabourah: Penis, Cock, Dick;

See Separate Article: SEX ISSUES IN THE ARAB-MUSLIM WORLD africame.factsanddetails.com

Arabic Names

Abu Bakr, the first Caliph

Arab men and women have a first name followed by the their father’s name, and then family or clan or tribe names. With Saddam Hussein al-Tikriti, Saddam is the first name, Hussein is the father’s name and Tikriti is the clan name, which in turn is derived from Saddam’s the town name of Tikrit.

Islam allows wives to bear the names of their parents and not necessarily that of their husbands. argued. Arab women generally don’t change their name when they marry. Many Arabs and Muslims have customarily not had family names. Instead they inherited their father’s given name with the prefixes “bin,” which means “son of,” and “binti,” which means “daughter of.” Such is the case with Osama bin Laden.

Common Muslim first names include: Maktoum, Ramadan, Abdullah, Omar, Muhammad and Ahmed. At the Asia Games in 2006, with many competitors from the Middle East and Muslim countries, there were at least 300 competitors named Muhammad. [Source: AFP, December 7, 2006]

Some important titles used in the Muslim and Arab world include: 1) Haj (an honorific that indicates that a person has participated in the Hajj 2) Sayyid (the title given to someone believed to be a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad); 3) “Ma’ ali” (a government minister); 4) “ Sa’ada” (a senior government official); “ Shaykh” for men and “ shaykah” for women (a member of royal family); and 5) “ duktour” for men and “ duktoura” for women (for a Ph.D. or M.D.)

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024