Home | Category: Arab Conquest After Muhammad / Arab Conquest After Muhammad

ARAB EXPANSION IN AFRICA

Minaret at the kasbah in Marrakech, Morocco

In sub-Sahara Africa along the Indian Ocean, Islam was spread peacefully by missionaries and merchants on ships. In the Sahara and west Africa, Islam was brought to places like Kumbi, Gao and Timbuktu by Tuareg caravans that carried salt, ivory, slaves, gold, sugar, cloth, leather and brassware. Islam spread as far as the Niger River. Malians traded with Berbers and Arabs for centuries before adopting Islam in the 11th century. By the 13th century Muslim merchants were well established on the coast of East Africa.

Charles F. Gallagher wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences”: In Africa, Islam spread unevenly at different periods, but it has continued to make impressive advances in modern times. Although peoples living along the Mediterranean shores of northern Africa were converted in the first wave of Arab conquest, Islam spread more gradually up the Nile and across the trade routes of the Sahara to reach the Chad area and, eventually, in the fifteenth century, northern Nigeria. By sea it moved down around the horn of east Africa to the Somali coast and Zanzibar. An island of resistance exists in the Abyssinian highlands, but Islam is heavily predominant today in Somalia, Zanzibar, and the Sudan, while important minorities exist in coastal Kenya, Tanganyika, and Mozambique. [Source: Charles F. Gallagher, “International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences”, 1960s, Encyclopedia.com]

Islamization in west Africa was furthered by brotherhood activity in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Islam has a majority today in Mauritania, Senegal, Mali, Niger, Chad, and probably Nigeria, large minorities in Guinea, Gambia, Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast, Cameroon, and the Central African Republic, and numerous adherents in the other states of west and central Africa as far south as Zambia and Rhodesia.

Websites on Islamic History: History of Islam: An encyclopedia of Islamic history historyofislam.com ; Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World oxfordislamicstudies.com ; Sacred Footsetps sacredfootsteps.com ; Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In”

by Hugh Kennedy Amazon.com ;

“In God's Path: The Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire” by Robert G. Hoyland, Peter Ganim, et al. Amazon.com ;

“In the Shadow of the Sword: The Birth of Islam and the Rise of the Global Arab Empire

by Tom Holland, Steven Crossley, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Arabs: A History” by Eugene Rogan Amazon.com ;

“The New Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 1, Formation of the Islamic World, 6th to 11th Centuries Amazon.com ;

“Arabs: A 3,000-Year History of Peoples, Tribes, and Empires” by Tim Mackintosh-Smith, Ralph Lister, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Arabs in History” by Bernard Lewis Amazon.com ;

“History of Islam” (3 Volumes) by Akbar Shah Najeebabadi and Abdul Rahman Abdullah Amazon.com ;

“Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong Amazon.com ;

”History of the Arab People” by Albert Hourani (1991) Amazon.com ;

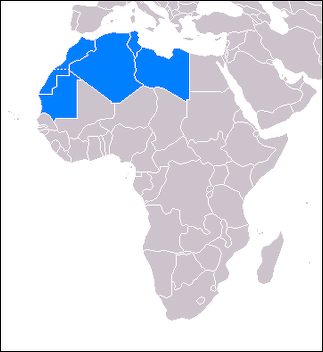

Spread of Islam in North Africa

The Sahara economy was largely based on camel caravans that moved goods between the heart of black Africa to the Mediterranean. Islam expanded into sub-Sahara Africa and would have spread further south were it not for tsetse flies wiping out the camels of Muslim missionaries and conquerors.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Between the eighth and ninth centuries, Arab traders and travelers, then African clerics, began to spread the religion along the eastern coast of Africa and to the western and central Sudan (literally, "Land of Black people"), stimulating the development of urban communities. Given its negotiated, practical approach to different cultural situations, it is perhaps more appropriate to consider Islam in Africa in terms of its multiple histories rather then as a unified movement. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“The spread of Islam throughout the African continent was neither simultaneous nor uniform. The first converts were the Sudanese merchants, followed by a few rulers and courtiers (Ghana in the eleventh century and Mali in the thirteenth century). The masses of rural peasants, however, remained little touched. In the eleventh century, the Almoravid intervention, led by a group of Berber nomads who were strict observers of Islamic law, gave the conversion process a new momentum in the Ghana empire and beyond. The spread of Islam throughout the African continent was neither simultaneous nor uniform, but followed a gradual and adaptive path. However, the only written documents at our disposal for the period under consideration derive from Arab sources (see, for instance, accounts by geographers al-Bakri and Ibn Battuta)."^/

“Islamic political and aesthetic influences on African societies remain difficult to assess. In some capital cities, such as Ghana and Gao, the presence of Muslim merchants resulted in the establishment of mosques. The Malian king Mansa Musa (r. 1312–37) brought back from a pilgrimage to Mecca the architect al-Sahili, who is often credited with the creation of the Sudano-Sahelian building style. Musa's brother, Mansa Suleyman, followed his path and encouraged the building of mosques, as well as the development of Islamic learning. Islam brought to Africa the art of writing and new techniques of weighting. The city of Timbuktu, for instance, flourished as a commercial and intellectual center, seemingly undisturbed by various upheavals. \^/

“Timbuktu began as a Tuareg settlement, was soon integrated into the Mali empire, then reclaimed by the Tuareg, and finally incorporated into the Songhai empire. In the sixteenth century, the majority of Muslim scholars in Timbuktu were of Sudanese origin. On the continent's eastern coast, Arabic vocabulary was absorbed into the Bantu languages to form the Swahili language. On the other hand, in many cases conversion for sub-Saharan Africans was probably a way to protect themselves against being sold into slavery, a flourishing trade between Lake Chad and the Mediterranean. For their rulers, who were not active proselytizers, conversion remained somewhat formal, a gesture perhaps aimed at gaining political support from the Arabs and facilitating commercial relationships. The strongest resistance to Islam seems to have emanated from the Mossi and the Bamana, with the development of the Segu kingdom. Eventually, sub-Saharan Africans developed their own brand of Islam, often referred to as "African Islam," with specific brotherhoods and practices." \^/

Websites and Resources: Islamic History: Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Islamic Civilization cyberistan.org ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Brief history of Islam barkati.net ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

Islam and Indigenous African Culture

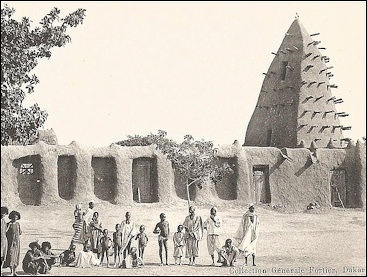

mosque in Timbuktu

According to a Harvard project on Islam and Indigenous African Culture: “Islam has been a highly influential factor on the African continent for over a millennium, adding much to the fabric of indigenous African cultures through various dimensions of its religious faith and visual language. As in other parts of the world, Islamic conversion was effected through trade and migration far more often than by force. In Africa, Islam has taken many unique forms as the product of many different conversion experiences. In West Africa, much of this conversion prior to the 18th century occurred through interaction with Islamicized Berber traders, who controlled the trans-Saharan trade routes. On the Swahili coast of East Africa, there are many legends of Muslim princes who came to the coast in the ninth century and settled. More accurately, it was likely Arab or Omani traders who settled, but the legends are valuable testaments to the unique weaving between Islam and indigenous cultures that has occurred throughout both Africa and the world. [Source: Islam and Indigenous African Culture, Baobad Project Narratives, Harvard, Internet Archive ^]

“The centuries of interaction between Muslims and non-Muslims in Africa brought about many changes in political, social and artistic structures in Africa, and the mosque is the quintessential expression of the symbiotic relationship between Islam and indigenous African culture. As in the rural mosque of Bourgouni illustrates, the built environment is the spatial representation of both Islamic faith - illustrated by the ??? as well as indigenous belief Ð the use of ostrich eggs, a symbol of fertility and purity. ^

“This mixture of the imported and the indigenous is not unique to the meeting of Islam and indigenous African cultures, however, the effects of Islam on indigenous African practices is far more profound, for it changes the ways in which creativity is regarded mentally, and, in some instances, changes the very identity of the maker herself/himself. Furthermore, this interaction shows the intricate relationship between creativity and societal change, for the introduction of Islamic visual practices brought with it new ways for indigenous African to express not only their beliefs but also a more diverse range of patrons and audiences. ^

“It would be shortsighted to see Islamicization as contributing to the death of indigenous African institutions; moreover, to do so would result in a failure to understand both African cultures as well as Islam. The narratives that follow are intended to give a brief overview of Islam in Africa, and, through using mosques as illustrations, the ways in which this relationship has enriched both African cultures and questioned ingrained definitions of Islamic artistic expression as well.” ^

Arab-Muslim Presence in North Africa

Maghreb (Maghrib): present-day Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Western Sahara and Mauritania

By 711 the Umayyads (a Muslim dynasty based in Damascus from 661 to 750), helped by Berber converts to Islam, had conquered all of North Africa. In 750 the Abbasids succeeded the Umayyads as Muslim rulers and moved the caliphate to Baghdad. Under the Abbasids, the Rustumid imamate (761–909) actually ruled most of the central Maghrib from Tahirt, southwest of Algiers. The imams gained a reputation for honesty, piety, and justice, and the court of Tahirt was noted for its support of scholarship. The Rustumid imams failed, however, to organize a reliable standing army, which opened the way for Tahirt’s demise under the assault of the Fatimid dynasty. [Source: Library of Congress, May 2008 **]

After the Arab conquest, North Africa was governed by a succession of amirs (commanders) who were subordinate to the caliph in Damascus and, after 750, in Baghdad. In 800 the Abbasid caliph Harun ar Rashid appointed as amir Ibrahim ibn Aghlab, who established a hereditary dynasty at Kairouan that ruled Ifriqiya and Tripolitania as an autonomous state that was subject to the caliph's spiritual jurisdiction and that nominally recognized him as its political suzerain. The Aghlabid amirs repaired the neglected Roman irrigation system, rebuilding the region's prosperity and restoring the vitality of its cities and towns with the agricultural surplus that was produced. **

At the top of the political and social hierarchy were the bureaucracy, the military caste, and an Arab urban elite that included merchants, scholars, and government officials who had come to Kairouan, Tunis, and Tripoli from many parts of the Islamic world. Members of the large Jewish communities that also resided in those cities held office under the amirs and engaged in commerce and the crafts. Converts to Islam often retained the positions of authority held traditionally by their families or class in Roman Africa, but a dwindling, Latinspeaking , Christian community lingered on in the towns until the eleventh century. The Aghlabids contested control of the central Mediterranean with the Byzantine Empire and, after conquering Sicily, played an active role in the internal politics of Italy.*

See Separate Article: ARAB-MUSLIM CONQUESTS AND PRESENCE IN NORTH AFRICA africame.factsanddetails.com

Islam Arrives in West Africa

According to a Harvard project on Islam and Indigenous African Culture: “During the ninth century, Islamicized Berber and Tuareg merchants began to carry Islam into West Africa by means of the trans-Sahraran trade routes connecting the Senegal and Niger River areas to the Maghrib. From trading towns on the northern edge of the Sahara, Muslims would carry goods as well as new ideas and visual practices to the cultures in the Savannah lying nearly one thousand miles to the south, resulting a slow but steady conversion of many of those with whom they had personal contact. [Source: Islam and Indigenous African Culture, Baobad Project Narratives, Harvard, Internet Archive ^]

Arab conqueror and general Uqba Ibn Nafi founded the Great Mosque of Kairouan (also known as the Mosque of Uqba), .the oldest and most important mosque in North Africa, in AD 670 in Kairouan, Tunisia

“This continued contact between Muslim traders and non-Muslims in West Africa quickly resulted in the conversion of black Africans to Islam. By the end of the tenth century, the Soninke (a Mande-speaking culture) in Mauritenia were Islamicized. These newly converted Muslims pushed further south to the Senegal River valley and southeast as far as the Niger River. Here, the Soninke were able to win more converts, thus pusing Islam from the edges of the African continent into its interior. ^

“Although the Soninke were successful in converting people to Islam, the most successful conversion was via the intercultural exhange made possible by the trans-Saharan trade. By the seventeenth century, every Sudanic state from Senegal, in the west, to Kanem, in the east, owed their ascendancy, in part, to Islam. In a certain sense, Islamic conversion linked the West African savannah through belief in a common god and access to similar new forms of political, social and artistic accouterments. ^

“For the medieval African kingdoms, particularly Mali and Songhay, Islam brought with it international fame and prestige. Cities such as Timbuktu, Gao and Kano became international centers of Islamic learning and Islamicized rulers, such as Mansa Musa of Mali, Askia Muhammed of Songhay and Idris Alooma of Bornu, became known throughout North Africa and the Near East for the wealth and intellectual activity of their kngdoms as well as thier piety. In fact, the reknown Muslim traveler Ibn Battuta visited Mansa Musa in the mid-fourteenth century and remarked on all of the above. ^

“Indigenous Manding and Songhay beliefs are rooted in the concept of ancestor worship. Within this system, these cultures strongly believe that the prescence of an ancestor in a given place will protect it as well as those in it from evil and misfortune. Spatially, this prescence takes its form in clusters of conical earthen and/or stone pillars which can be seen througout the savannah. In her study of Islam and African cultures, Labelle Prussin noted that with the advent of Islam in these areas, the pillar found its expression through the minaret of the mosque, thus, as the author states, taking on multiple layers of meaning. ^

“The Sudanic states were an important link in the economic lifeblood of Islam, for they were the intermediaries between the Muslim merchants to the north and the products of the forest areas to the south. Islamicized merchants, particularly the Dyula and the Hausa, controlled the trade between the sdavannah and the forest. Eventually, they too became agents for the spread of Islam. Their travels brought the Muslim faith into present-day Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Cote D'Ivoire, Ghana, Ghana, Togo, Benin, southern Nigeria and Cameroon. ^

mosque in Djenne, Mali

“This constant interchange between Islam and indigenous African cultures gave rise to a change in African social and political institutions and was instrumental in changing artistic production. The mosques of West Africa are a striking example of the resultant heterogeneity in artistic and spatial languages as well as social practices which took unique form in each of the setting into which the two came together.” ^ In Ghana, “a Batakari, or war shirt, combines references to the Akan's military prowess, which overpowers their neighbors, with a borrowing of traditions outside of their own, which may indicate some reverence for other cultures. The efficacy of the war shirt is derived from the handwritten lines of the Qur’an which are encased in the amulets which adorn the shirt. ^

“The integration of Islamic writing and decorative forms could be seen as a creative by-product of a period of inter-tribal warfare in the nineteenth century. Strife between the Asante and other neighbors, such as the coastal Fante people, was escalated following the introduction of firearms by the Europeans. ^

Islam in West Africa

According to a Harvard project on Islam and Indigenous African Culture: “During the ninth century, Islamicized Berber and Tuareg merchants began to carry Islam into West Africa by means of the trans-Sahraran trade routes connecting the Senegal and Niger River areas to the Maghrib. From trading towns on the northern edge of the Sahara, Muslims would carry goods as well as new ideas and visual practices to the cultures in the Savannah lying nearly one thousand miles to the south, resulting a slow but steady conversion of many of those with whom they had personal contact. [Source: Islam and Indigenous African Culture, Baobad Project Narratives, Harvard, Internet Archive ^]

“This continued contact between Muslim traders and non-Muslims in West Africa quickly resulted in the conversion of black Africans to Islam. By the end of the tenth century, the Soninke (a Mande-speaking culture) in Mauritenia were Islamicized. These newly converted Muslims pushed further south to the Senegal River valley and southeast as far as the Niger River. Here, the Soninke were able to win more converts, thus pusing Islam from the edges of the African continent into its interior. ^

mosque in Mali

“Although the Soninke were successful in converting people to Islam, the most successful conversion was via the intercultural exchange made possible by the trans-Saharan trade. By the seventeenth century, every Sudanic state from Senegal, in the west, to Kanem, in the east, owed their ascendancy, in part, to Islam. In a certain sense, Islamic conversion linked the West African savannah through belief in a common god and access to similar new forms of political, social and artistic accouterments. ^

“For the medieval African kingdoms, particularly Mali and Songhay, Islam brought with it international fame and prestige. Cities such as Timbuktu, Gao and Kano became international centers of Islamic learning and Islamicized rulers, such as Mansa Musa of Mali, Askia Muhammed of Songhay and Idris Alooma of Bornu, became known throughout North Africa and the Near East for the wealth and intellectual activity of their kngdoms as well as their piety. In fact, the reknown Muslim traveler Ibn Battuta visited Mansa Musa in the mid-fourteenth century and remarked on all of the above. ^

“The Sudanic states were an important link in the economic lifeblood of Islam, for they were the intermediaries between the Muslim merchants to the north and the products of the forest areas to the south. Islamicized merchants, particularly the Dyula and the Hausa, controlled the trade between the savannah and the forest. Eventually, they too became agents for the spread of Islam. Their travels brought the Muslim faith into present-day Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Côté D'Ivoire, Ghana, Ghana, Togo, Benin, southern Nigeria and Cameroon. ^

“This constant interchange between Islam and indigenous African cultures gave rise to a change in African social and political institutions and was instrumental in changing artistic production. The mosques of West Africa are a striking example of the resultant heterogeneity in artistic and spatial languages as well as social practices which took unique form in each of the setting into which the two came together.

Arab-Muslim View on "Black Africans" in 860

In “On the Zanj” ["Black Africans"] from “The Essays” Abû Ûthmân al-Jâhiz wrote in A.D. 860: “Everybody agrees that there is no people on earth in whom generosity is as universally well developed as the Zanj. These people have a natural talent for dancing to the rhythm of the tambourine, without needing to learn it. There are no better singers anywhere in the world, no people more polished and eloquent, and no people less given to insulting language. No other nation can surpass them in bodily strength and physical toughness. One of them will lift huge blocks and carry heavy loads that would be beyond the strength of most Bedouins or members of other races. They are courageous, energetic, and generous, which are the virtues of nobility, and also good-tempered and with little propensity to evil. They are always cheerful, smiling, and devoid of malice, which is a sign of noble character. [Source: “On the Zanj ["Black Africans"] by Abû Ûthmân al-Jâhiz, from The Essays, c. 860 CE]

“The Zanj say to the Arabs: You are so ignorant that during the jahiliyya you regarded us as your equals when it came to marrying Arab women, but with the advent of the justice of Islam you decided this practice was bad. Yet the desert is full of Zanj married to Arab wives, and they have been princes and kings and have safeguarded your rights and sheltered you against your enemies.

“The Zanj say that God did not make them black in order to disfigure them; rather it is their environment that made them so. The best evidence of this is that there are black tribes among the Arabs, such as the Banu Sulaim bin Mansur, and that all the peoples settled in the Harra, besides the Banu Sulaim are black. These tribes take slaves from among the Ashban to mind their flocks and for irrigation work, manual labor, and domestic service, and their wives from among the Byzantines; and yet it takes less than three generations for the Harra to give them all the complexion of the Banu Sulaim. This Harra is such that the gazelles, ostriches, insects, wolves, foxes, sheep, asses, horses and birds that live there are all black. White and black are the results of environment, the natural properties of water and soil, distance from the sun, and intensity of heat. There is no question of metamorphosis, or of punishment, disfigurement or favor meted out by Allah. Besides, the land of the Banu Sulaim has much in common with the land of the Turks, where the camels, beasts of burden, and everything belonging to these people is similar in appearance: everything of theirs has a Turkish look.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024