Home | Category: Arab Conquest After Muhammad / Arab Conquest After Muhammad

ARAB VICTORIES IN EGYPT AND NORTH AFRICA

Egypt was invaded in 639. It fell two years later in 641 after a bloody, seven-month siege of a fortress called Babylon at present-day Cairo was taken by the Arab leader Amr ibn al-As. Eighteen months later Alexandria, the Byzantines’ main naval base, was taken. Alexandria was second only to Constantinople itself in importance. The spoils taken by the Arabs included "4,000 villas with 4,000 baths and 40,000 taxpaying Jews and 400 places of entertainment for the royalty."

By 641, Muslims controlled Syria, Palestine and Egypt and the Persian empire had been defeated. After this the rate of conquest slowed somewhat. The Arabs made no headway in the Byzantine heartland of Anatolia. In 674, the Arabs laid siege to Constantinople for three years and tried again in 717 but were ultimately unsuccessful in dislodging the Byzantines from their capital. Generally, the Arabs were aware when the reached the limits of their conquest and sought friendly relations with their neighbors.

Under Caliph Uthman, between 644 and 650, Muslims conquered Cyprus and Tripoli in North Africa and were able to control the eastern Mediterranean and claimed Armenia and part of the Caucasus.

Arab armies and Islam swept into North Africa under the Omayyad caliphs (661-750). At that time North Africa was very sparsely populated. Within a relatively short period of time North Africa and Spain were added to the Arab-Muslim empire. In 682, a general named Ubqa ibn Nafi moved westwards from the Nile, leading his cavalry across northern Africa and claiming what is now Libya, Tunisia Algeria and Morocco. After galloping his horse into the Atlantic near Agadir, Morocco, he exclaimed: "Lord God, bear witness were I not stopped by the sea I would conquer more lands for Thy sake!"

Ubqa's successor's established a presence in the area and over time the Byzantine strongholds—Tripoli, Carthage and Tangier—fell to the Arabs and the Mediterranean became dominated by Muslims. Arab armies marched into Europe across the straits of Gibralter in 711 A.D. Under Muslim rule, large cities grew in Fez and Marrakesh, where the caravan routes converged into the coastal agricultural areas large cities sprang up.

Websites on Islamic History: History of Islam: An encyclopedia of Islamic history historyofislam.com ; Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World oxfordislamicstudies.com ; Sacred Footsetps sacredfootsteps.com ; Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In”

by Hugh Kennedy Amazon.com ;

“In God's Path: The Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire” by Robert G. Hoyland, Peter Ganim, et al. Amazon.com ;

“In the Shadow of the Sword: The Birth of Islam and the Rise of the Global Arab Empire

by Tom Holland, Steven Crossley, et al. Amazon.com ;

“After the Prophet: The Epic Story of the Shia-Sunni Split in Islam” by Lesley Hazleton and Blackstone Amazon.com ;

“The Arabs: A History” by Eugene Rogan Amazon.com ;

“The New Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 1, Formation of the Islamic World, 6th to 11th Centuries Amazon.com ;

“Arabs: A 3,000-Year History of Peoples, Tribes, and Empires” by Tim Mackintosh-Smith, Ralph Lister, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Arabs in History” by Bernard Lewis Amazon.com ;

“History of Islam” (3 Volumes) by Akbar Shah Najeebabadi and Abdul Rahman Abdullah Amazon.com ;

“Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Muslim World: From Its Origins to the Dawn of Modernity”

by Michael A. Cook, Ric Jerrom, et al. Amazon.com ;

”History of the Arab People” by Albert Hourani (1991) Amazon.com ;

“Islam Explained: A Short Introduction to History, Teachings, and Culture” by Ahmad Rashid Salim Amazon.com ;

“No God but God” by Reza Aslan Amazon.com ;

“Muhammad: A Prophet for Our Time” by Karen Armstrong Amazon.com ;

“The Messenger: The Meanings of the Life of Muhammad” by Tarqi Ramadan Amazon.com

Arab Conquest of Egypt

letter from Huhammad to Al-Muqawqis, a ruler in Egypt

Perhaps the most important event to occur in Egypt since the unification of the Two Lands by King Menes was the Arab conquest of Egypt.The conquest of the country by the armies of Islam under the command of the Muslim hero, Amr ibn al As, transformed Egypt from a predominantly Christian country to a Muslim country in which the Arabic language and culture were adopted even by those who clung to their Christian or Jewish faiths. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990 *]

The conquest of Egypt was part of the Arab/Islamic expansion that began when the Prophet Muhammad died and Arab tribes began to move out of the Arabian Peninsula into Iraq and Syria. Amr ibn al As, who led the Arab army into Egypt, was made a military commander by the Prophet himself. Amr crossed into Egypt on December 12, 639, at Al Arish with an army of about 4,000 men on horseback, armed with lances, swords, and bows. The army's objective was the fortress of Babylon (Bab al Yun) opposite the island of Rawdah in the Nile at the apex of the Delta. The fortress was the key to the conquest of Egypt because an advance up the Delta to Alexandria could not be risked until the fortress was taken.*

In June 640, reinforcements for the Arab army arrived, increasing Amr's forces to between 8,000 and 12,000 men. In July the Arab and Byzantine armies met on the plains of Heliopolis. Although the Byzantine army was routed, the results were inconclusive because the Byzantine troops fled to Babylon. Finally, after a six-month siege, the fortress fell to the Arabs on April 9, 641.The Arab army then marched to Alexandria, which was not prepared to resist despite its well fortified condition. Consequently, the governor of Alexandria agreed to surrender, and a treaty was signed in November 641. The following year, the Byzantines broke the treaty and attempted unsuccessfully to retake the city.*

Muslims Defeat the Byzantines Again Egypt (642)

Sawirus ibn al-Muqaffa wrote in the “History of the Patriarchs of the Coptic Church of Alexandria”: “And in those days Heraclius saw a dream in which it was said to him: "Verily there shall come against you a circumcised nation, and they shall vanquish you and take possession of the land." So Heraclius thought that they would be the Jews, and accordingly gave orders that all the Jews and Samaritans should be baptized in all the provinces which were under his dominion. [Source: Sawirus ibn al-Muqaffa, “History of the Patriarchs of the Coptic Church of Alexandria,” trans. Basil Evetts, (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1904), pt. I, ch. 1, from Patrologia Orientalis, Vol. I, pp. 489-497, reprinted in Deno John Geanakoplos, “Byzantium: Church, Society, and Civilization Seen Through Contemporary Eyes,” (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), pp. 336-338, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

But after a few days there appeared a man of the Arabs, from the southern districts, that is to say, from Mecca or its neighbourhood, whose name was Muhammad; and he brought back the worshippers of idols to the knowledge of the One God, and bade them declare that Muhammad was his apostle; and his nation were circumcised in the Hesh, not by the law, and prayed towards the South, turning towards a place which they called the Kaabah. And he took possession of Damascus and Syria, and crossed the Jordan, and dammed it up. And the Lord abandoned the army of the Romans before him, as a punishment for their corrupt faith, and because of the anathemas uttered against them, on account of the council of Chalcedon, by the ancient fathers.

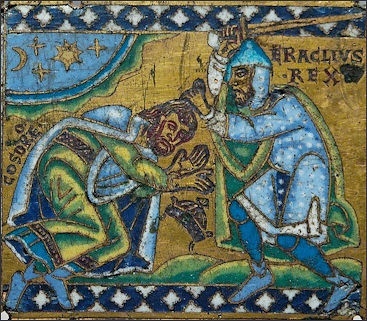

Byzantine leader Heraclius defeated by the Muslims

“When Heraclius saw this, he assembled all his troops from Egypt as far as the frontiers of Aswan. And he continued for three years to pay to the Muslims the taxes which he had demanded for the purpose of applying them to himself and all his troops; and they used to call the tax the bakt, that is to say that it was a sum levied at so much a head. And this went on until Heraclius had paid to the Muslims the greater part of his money; and many people died through the troubles which they had endured.

“So when ten years were over of the rule of Heraclius together with the Colchian, who sought for the patriarch Benjamin, while he was fleeing from him from place to place, hiding himself in the fortified churches, the prince of the Muslims sent an army to Egypt, under one of his trusty companions, named Amr ibn Al-Asi, in the year 357 of Diocletian, the slayer of the martyrs. And this army of Islam came down into Egypt in great force, on the twelfth day of Baunah, which is the sixth of June, according to the months of the Romans.

“Now the commander Amr had destroyed the fort, and burnt the boats with fire, and defeated the Romans, and taken possession of part of the country. For he had first arrived by the desert; and the horsemen took the road through the mountains, until they arrived at a fortress built of stone, between Upper Egypt and the Delta, called Babylon. So they pitched their tents there, until they were prepared to fight the Romans, and make war against them; and afterwards they named that place, I mean the fortress, in their language, Bablun Al-Fustat; and that is its name to the present day.

“After fighting three battles with the Romans, the Muslims conquered them. So when the chief men of the city saw these things, they went to Amr, and received a certificate of security for the city, that it might not be plundered. This kind of treaty which Muhammad, the chief of the Arabs, taught them, they called the Law; and he says with regard to it: "As for the province of Egypt and any city that agrees with its inhabitants to pay the land-tax to you and to submit to your authority, make a treaty with them, and do them no injury. But plunder and take as prisoners those that will not consent to this and resist you." For this reason the Muslims kept their hands off the province and its inhabitants, but destroyed the nation of the Romans, and their general who was named Marianus. And those of the Romans who escaped fled to Alexandria, and shut its gates upon the Arabs, and fortified themselves within the city.

“And in the year 360 of Diocletian, in the month of December, three years after Amr had taken possession of Memphis, the Muslims captured the city of Alexandria, and destroyed its walls, and burnt many churches with fire. And they burnt the church of Saint Mark, which was built by the sea, where his body was laid; and this was the place to which the father and patriarch, Peter the Martyr, went before his martyrdom, and blessed Saint Mark, and committed to him his reasonable flock, as he had received it. So they burnt this place and the monasteries around it....

Conquest of Alexandria

fighting in Egypt

The 9th-century Arab historian Al-Baladhuri wrote: “'Amr kept his way until he arrived in Alexandria whose inhabitants he found ready to resist him, but the Copts in it preferred peace. Al-Mukaukis communicated with 'Amr and asked him for peace and a truce for a time; but 'Amr refused. Al-Mukaukis then ordered that the women stand on the wall with their faces turned towards the city, and that the men stand armed, with their faces towards the Moslems, thus hoping to scare them. 'Amr sent word, saying, "We see what you have done. It was not by mere numbers that we conquered those we have conquered. We have met your king Heraclius, and there befell him what has befallen him." Hearing this, al-Mukaukis said to his followers, "These people are telling the truth. They have chased our king from his kingdom as far as Constantinople. It is much more preferable, therefore, that we submit." His followers, however, spoke harshly to him and insisted on fighting. The Moslems fought fiercely against them and invested them for three months. At last, 'Amr reduced the city by the sword and plundered all that was in it, sparing its inhabitants of whom none was killed or taken captive. He reduced them to the position of dhimmis like the people of Alyunah. He communicated the news of the victory to 'Umar through Mu'awiyah ibn-Hudaij al-Kindi (later as-Sakuni) and sent with him the fifth. [Source: Philip Hitti, trans., The Origins of the Islamic State, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1916), Vol. I, pp. 346-349, reprinted in Deno John Geanakoplos, Byzantium: Church, Society, and Civilization Seen Through Contemporary Eyes, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), pp. 338-339.

“The Greeks wrote to Constantine, son of Heraclius, who was their king at that time, telling him how few the Moslems in Alexandria were, and how humiliating the Greeks' condition was, and how they had to pay poll-tax. Constantine sent one of his men, called Manuwil, with three hundred ships full of fighters. Manuwil entered Alexandria and killed all the guard that was in it, with the exception of a few who by the use of subtle means took to flight and escaped. This took place in the year 25. Hearing the news, 'Amr set out at the head of 15,000 men and found the Greek fighters doing mischief in the Egyptian villages next to Alexandria. The Moslems met them and for one hour were subjected to a shower of arrows, during which they were covered by their shields. They then advanced boldly and the battle raged with great ferocity until the polytheists were routed; and nothing could divert or stop them before they reached Alexandria. Here they fortified themselves and set mangonels. 'Amr made a heavy assault, set the ballistae, and destroyed the walls of the city. He pressed the fight so hard until he entered the city by assault, killed the fathers and carried away the children as captives. Some of its Greek inhabitants left to join the Greeks somewhere else; and Allah's enemy, Manuwil, was killed. 'Amr and the Moslems destroyed the wall of Alexandria in pursuance of a vow that 'Amr had made to that effect, in case he reduced the city....'Amr ibn-al-Asi conquered Alexandria, and some Moslems took up their abode in it as a cavalry guard.

Sawirus ibn al-Muqaffa wrote in the “History of the Patriarchs of the Coptic Church of Alexandria”: “When Amr took full possession of the city of Alexandria, and settled its affairs, that infidel, the governor of Alexandria, feared, he being both prefect and patriarch of the city under the Romans, that Amr would kill him; therefore he sucked a poisoned ring, and died on the spot. But Sanutius, the believing dux, made known to Amr the circumstances of that militant father, the patriarch Benjamin, and how he was a fugitive from the Romans, through fear of them. Then Amr, son of Al-Asi, wrote to the provinces of Egypt a letter, in which he said: "There is protection and security for the place where Benjamin, the patriarch of the Coptic Christians is, and peace from God; therefore let him come forth secure and tranquil, and administer the affairs of his Church, and the government of his nation." Therefore when the holy Benjamin heard this, he returned to Alexandria with great joy, clothed with the crown of patience and sore conflict which had befallen the orthodox people through their persecution by the heretics, after having been absent during thirteen years, ten of which were years of Heraclius, the misbelieving Roman, with the three years before the Muslims conquered Alexandria. When Benjamin appeared, the people and the whole city rejoiced, and made his arrival known to Sanutius, the dux who believed in Christ, who had settled with the commander Amr that the patriarch should return, and had received a safe-conduct from Amr for him. Thereupon Sanutius went to the commander and announced that the patriarch had arrived, and Amr gave orders that Benjamin should be brought before him with honour and veneration and love. And Amr, when he saw the patriarch, received him with respect, and said to his companions and private friends: "Verily in all the lands of which we have taken possession hitherto I have never seen a man of God like this man." For the Father Benjamin was beautiful of countenance, excellent in speech, discoursing with calmness and dignity. [Source: Sawirus ibn al-Muqaffa, “History of the Patriarchs of the Coptic Church of Alexandria,” trans. Basil Evetts, (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1904), pt. I, ch. 1, from Patrologia Orientalis, Vol. I, pp. 489-497, reprinted in Deno John Geanakoplos, “Byzantium: Church, Society, and Civilization Seen Through Contemporary Eyes,” (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), pp. 336-338, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“Then Amr turned to him, and said to him: "Resume the government of all your churches and of your people, and administer their affairs. And if you will pray for me, that I may go to the West and to Pentapolis, and take possession of them, as I have of Egypt, and return to you in safety and speedily, I will do for you all that you shall ask of me." Then the holy Benjamin prayed for Amr, and pronounced an eloquent discourse, which made Amr and those present with him marvel, and which contained words of exhortation and much profit for those that heard him; and he revealed certain matters to Amr, and departed from his presence honoured and revered. And all that the blessed father said to the commander Amr, son of Al-Asi, he found true, and not a letter of it was unfulfilled.

Arab Conquest of North Africa

Arab armies and Islam swept into North Africa under the Umayyad caliphs (661-750). At that time North Africa was very sparsely populated. Within a relatively short period of time North Africa and Spain were added to the Arab-Muslim empire.

Within a generation, Arab armies had carried Islam north and east from Arabia and westward into North Africa. In 642 Amr ibn al As, an Arab general under Caliph Umar I, conquered Cyrenaica, establishing his headquarters at Barce. Two years later, he moved into Tripolitania, where, by the end of the decade, the isolated Byzantine garrisons on the coast were overrun and Arab control of the region consolidated. Uqba bin Nafi, an Arab general under the ruling Caliph, invaded Fezzan in 663, forcing the capitulation of Germa. Stiff Berber resistance in Tripolitania had slowed the Arab advance to the west, however, and efforts at permanent conquest were resumed only when it became apparent that the Maghrib could be opened up as a theater of operations in the Muslim campaign against the Byzantine Empire. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Libya: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1987*]

In 670 the Arabs surged into the Roman province of Africa (transliterated Ifriqiya in Arabic; present-day Tunisia), where Uqba founded the city of Kairouan (present-day Al Qayrawan) as a military base for an assault on Byzantine-held Carthage. Twice the Berber tribes compelled them to retreat into Tripolitania, but each time the Arabs, employing recently converted Berber tribesmen recruited in Tripolitania,

In 682, a general named Uqba ibn Nafi moved westwards from the Nile, leading his cavalry across northern Africa and claiming what is now Libya, Tunisia Algeria and Morocco. After galloping his horse into the Atlantic near Agadir, Morocco, he exclaimed: "Lord God, bear witness were I not stopped by the sea I would conquer more lands for Thy sake!" On his return, he was ambushed by the Berber-Byzantine coalition at Tehouda (Thabudeos) south Vescera, defeated and killed. As a result of this crushing defeat, the Arabs were expelled from the area of modern Tunisia for a decade. Ubqa's successors later established a presence in the area and over time the Byzantine strongholds—Tripoli, Carthage and Tangier—fell to the Arabs and the Mediterranean became dominated by Muslims.

Arab and Berber forces returned in greater force, and in 693 they took Carthage. The Arabs cautiously probed the western Maghrib and in 710 invaded Morocco, carrying their conquests to the Atlantic. Arab armies marched into Europe across the straits of Gibralter in 711 A.D. In 712 they mounted an invasion of Spain and in three years had subdued all but the mountainous regions in the extreme north. Muslim Spain (called Andalusia), the Maghrib (including Tripolitania), and Cyrenaica were systematically organized under the political and religious leadership of the Umayyad caliph of Damascus.*

Arab-Muslim Presence in North Africa

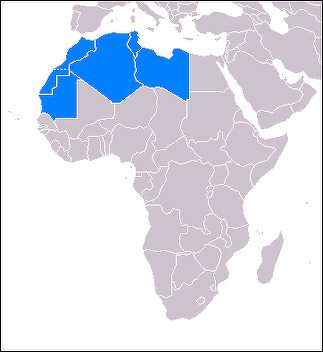

Maghreb (Maghrib): present-day Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Western Sahara and Mauritania

The first Arab military expeditions into the Maghrib, between 642 and 669, resulted in the spread of Islam. By 711 the Umayyads (a Muslim dynasty based in Damascus from 661 to 750), helped by Berber converts to Islam, had conquered all of North Africa. In 750 the Abbasids succeeded the Umayyads as Muslim rulers and moved the caliphate to Baghdad. Under the Abbasids, the Rustumid imamate (761–909) actually ruled most of the central Maghrib from Tahirt, southwest of Algiers. The imams gained a reputation for honesty, piety, and justice, and the court of Tahirt was noted for its support of scholarship. The Rustumid imams failed, however, to organize a reliable standing army, which opened the way for Tahirt’s demise under the assault of the Fatimid dynasty. [Source: Library of Congress, May 2008 **]

After the Arab conquest, North Africa was governed by a succession of amirs (commanders) who were subordinate to the caliph in Damascus and, after 750, in Baghdad. In 800 the Abbasid caliph Harun ar Rashid appointed as amir Ibrahim ibn Aghlab, who established a hereditary dynasty at Kairouan that ruled Ifriqiya and Tripolitania as an autonomous state that was subject to the caliph's spiritual jurisdiction and that nominally recognized him as its political suzerain. The Aghlabid amirs repaired the neglected Roman irrigation system, rebuilding the region's prosperity and restoring the vitality of its cities and towns with the agricultural surplus that was produced. **

At the top of the political and social hierarchy were the bureaucracy, the military caste, and an Arab urban elite that included merchants, scholars, and government officials who had come to Kairouan, Tunis, and Tripoli from many parts of the Islamic world. Members of the large Jewish communities that also resided in those cities held office under the amirs and engaged in commerce and the crafts. Converts to Islam often retained the positions of authority held traditionally by their families or class in Roman Africa, but a dwindling, Latinspeaking , Christian community lingered on in the towns until the eleventh century. The Aghlabids contested control of the central Mediterranean with the Byzantine Empire and, after conquering Sicily, played an active role in the internal politics of Italy.*

Muslim Rule in Egypt

Fustat (Cairo)

Muslim conquerors habitually gave the people they defeated three alternatives: converting to Islam, retaining their religion with freedom of worship in return for the payment of the poll tax, or war. In surrendering to the Arab armies, the Byzantines agreed to the second option. The Arab conquerors treated the Egyptian Copts well. During the battle for Egypt, the Copts had either remained neutral or had actively supported the Arabs. After the surrender, the Coptic patriarch was reinstated, exiled bishops were called home, and churches that had been forcibly turned over to the Byzantines were returned to the Copts. Amr allowed Copts who held office to retain their positions and appointed Copts to other offices. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990 *]

Amr moved the capital south to a new city called Al Fustat (present-day Old Cairo). The mosque he built there bears his name and still stands, although it has been much rebuilt.For two centuries after the conquest, Egypt was a province ruled by a line of governors appointed by the caliphs in the east. Egypt provided abundant grain and tax revenue. In time most of the people accepted the Muslim faith, and the Arabic language became the language of government, culture, and commerce. The Arabization of the country was aided by the continued settlement of Arab tribes in Egypt.*

From the time of the conquest onward, Egypt's history was intertwined with the history of the Arab world. Thus, in the eighth century, Egypt felt the effects of the Arab civil war that resulted in the defeat of the Umayyad Dynasty, the establishment of the Abbasid Caliphate, and the transfer of the capital of the empire from Damascus to Baghdad. For Egypt, the transfer of the capital farther east meant a weakening of control by the central government. When the Abbasid Caliphate began to decline in the ninth century, local autonomous dynasties arose to control the political, economic, social, and cultural life of the country.*

Arab Rule of North Africa

Spain and Morocco seceded from the Abbasid caliphate in A.D. 756, six years after the Abbasid dynasty was founded. An independent kingdom was set up under the leadership of an Umayyad family member, claiming "closer descent to Muhammad." .

Arab rule in North Africa — as elsewhere in the Islamic world in the eighth century — had as its ideal the establishment of political and religious unity under a caliphate (the office of the Prophet's successor as supreme earthly leader of Islam) governed in accord with sharia (a legal system) administered by qadis (religious judges) to which all other considerations, including tribal loyalties, were subordinated. The sharia was based primarily on the Quran and the hadith and derived in part from Arab tribal and market law. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Libya: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1987*]

prayer tent

Arab rule was easily imposed in the coastal farming areas and on the towns, which prospered again under Arab patronage. Townsmen valued the security that permitted them to practice their commerce and trade in peace, while the Punicized farmers recognized their affinity with the Semitic Arabs to whom they looked to protect their lands; in Cyrenaica, Monophysite adherents of the Coptic Church had welcomed the Muslim Arabs as liberators from Byzantine oppression. Communal and representative Berber tribal institutions, however, contrasted sharply and frequently clashed with the personal and authoritarian government that the Arabs had adopted under Byzantine influence. While the Arabs abhorred the tribal Berbers as barbarians, the Berbers in the hinterland often saw the Arabs only as an arrogant and brutal soldiery bent on collecting taxes.*

Under Muslim rule, large cities grew in Fez and Marrakesh, where the caravan routes converged into the coastal agricultural areas large cities sprang up. The Arabs formed an urban elite in North Africa, where they had come as conquerors and missionaries, not as colonists. Their armies had traveled without women and married among the indigenous population, transmitting Arab culture and Islamic religion over a period of time to the townspeople and farmers. Although the nomadic tribes of the hinterland had stoutly resisted Arab political domination, they rapidly accepted Islam. Once established as Muslims, however, the Berbers, with their characteristic love of independence and impassioned religious temperament, shaped Islam in their own image, enthusiastically embracing schismatic Muslim sects--often traditional folk religion barely distinguished as Islam--as a way of breaking from Arab control.*

One such sect, the Kharijites (seceders; literally, "those who emerge from impropriety") surfaced in North Africa in the mideighth century, proclaiming its belief that any suitable Muslim candidate could be elected caliph without regard to his race, station, or descent from the Prophet. The attack on the Arab monopoly of the religious leadership of Islam was explicit in Kharijite doctrine, and Berbers across the Maghrib rose in revolt in the name of religion against Arab domination. The rise of the Kharijites coincided with a period of turmoil in the Arab world during which the Abbasid dynasty overthrew the Umayyads and relocated the caliphate in Baghdad. In the wake of the revolt, Kharijite sectarians established a number of theocratic tribal kingdoms, most of which had short and troubled histories. One such kingdom, however, founded by the Bani Khattab, succeeded in putting down roots in remote Fezzan, where the capital, Zawilah, developed into an important oasis trading center.*

Islamization and Arabization of the Maghrib

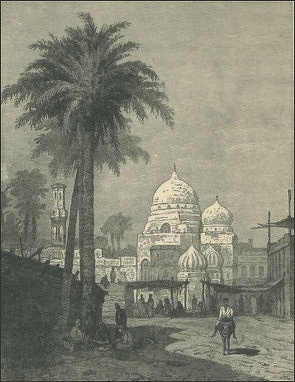

El Qaraouiyyine Mosque in Fez, Morocco

Unlike the invasions of previous religions and cultures, the coming of Islam, which was spread by Arabs, was to have pervasive and longlasting effects on the Maghrib. The new faith, in its various forms, would penetrate nearly all segments of society, bringing with it armies, learned men, and fervent mystics, and in large part replacing tribal practices and loyalties with new social norms and political idioms. [Source: Helen Chapan Metz, ed. Algeria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

Nonetheless, the Islamization and arabization of the region were complicated and lengthy processes. Whereas nomadic Berbers were quick to convert and assist the Arab invaders, not until the twelfth century under the Almohad Dynasty did the Christian and Jewish communities become totally marginalized.*

The first Arab military expeditions into the Maghrib, between 642 and 669, resulted in the spread of Islam. These early forays from a base in Egypt occurred under local initiative rather than under orders from the central caliphate. When the seat of the caliphate moved from Medina to Damascus, however, the Umayyads (a Muslim dynasty ruling from 661 to 750) recognized that the strategic necessity of dominating the Mediterranean dictated a concerted military effort on the North African front. In 670, therefore, an Arab army under Uqba ibn Nafi established the town of Al Qayrawan about 160 kilometers south of present-day Tunis and used it as a base for further operations.*

Abu al Muhajir Dina, Uqba's successor, pushed westward into Algeria and eventually worked out a modus vivendi with Kusayla, the ruler of an extensive confederation of Christian Berbers. Kusayla, who had been based in Tilimsan (Tlemcen), became a Muslim and moved his headquarters to Takirwan, near Al Qayrawan.*

This harmony was short-lived, however. Arab and Berber forces controlled the region in turn until 697. By 711 Umayyad forces helped by Berber converts to Islam had conquered all of North Africa. Governors appointed by the Umayyad caliphs ruled from Al Qayrawan, the new wilaya (province) of Ifriqiya, which covered Tripolitania (the western part of present-day Libya), Tunisia, and eastern Algeria.*

Arabs and Berbers

Arab conquerors converted the indigenous Berber population to Islam, but Berber tribes retained their customary laws. The Arabs abhorred the Berbers as barbarians, while the Berbers often saw the Arabs as only an arrogant and brutal soldiery bent on collecting taxes. Once established as Muslims, the Berbers shaped Islam in their own image and embraced schismatic Muslim sects, which, in many cases, were simply folk religion barely disguised as Islam, as their way of breaking from Arab control. [Source: Library of Congress, May 2006 **]

The eleventh and twelfth centuries witnessed the founding of several great Berber dynasties led by religious reformers and each based on a tribal confederation that dominated the Maghrib (also seen as Maghreb; refers to North Africa west of Egypt) and Spain for more than 200 years. The Berber dynasties (Almoravids, Almohads, and Merinids) gave the Berber people some measure of collective identity and political unity under a native regime for the first time in their history, and they created the idea of an “imperial Maghrib” under Berber aegis that survived in some form from dynasty to dynasty. But ultimately each of the Berber dynasties proved to be a political failure because none managed to create an integrated society out of a social landscape dominated by tribes that prized their autonomy and individual identity.**

Paradoxically, the spread of Islam among the Berbers did not guarantee their support for the Arab-dominated caliphate. The ruling Arabs alienated the Berbers by taxing them heavily; treating converts as second-class Muslims; and, at worst, by enslaving them. As a result, widespread opposition took the form of open revolt in 739-40 under the banner of Kharijite Islam.

Kharijites

The Berbers used the schism between Sunnis and Shiities to carve out their unique niche in Islam. They embraced, the Kharijite sect of Islam, a puritanical movement that originally supported Ali , the cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad, but later rejected the leadership of Ali after his supporters battled with forces loyal to one of Muhammad’s wives and revolted against the rule of the caliphs in Iraq and the Maghreb. Ali was murdered by a knife-carrying Kharajite assassin on his way to a mosque in Kufa, near Najaf in Iraq in A.D. 661.

Kharijism was a puritanical form of Shiite Islam that developed over disagreements over the succession of the caliph. It was regarded as heretical by the Muslim status quo. Kharijism took root in the countryside of North Africa and denounced people living in the cities as decadent. Kharajitism was particularly strong in a Sijilmassa, a great caravan center in southern Morocco, and Tahert, in present-day Algeria. These kingdoms became strong in the 8th and 9th centuries.

The Kharijites objected to Ali, the fourth caliph, making peace with the Umayyads in 657 and left Ali's camp (khariji means "those who leave"). The Kharijites had been fighting Umayyad rule in the East, and many Berbers were attracted by the sect's egalitarian precepts. For example, according to Kharijism, any suitable Muslim candidate could be elected caliph without regard to race, station, or descent from the Prophet Muhammad.*

After the revolt, Kharijites established a number of theocratic tribal kingdoms, most of which had short and troubled histories. Others, however, like Sijilmasa and Tilimsan, which straddled the principal trade routes, proved more viable and prospered. In 750 the Abbasids, who succeeded the Umayyads as Muslim rulers, moved the caliphate to Baghdad and reestablished caliphal authority in Ifriqiya, appointing Ibrahim ibn Al Aghlab as governor in Al Qayrawan. Although nominally serving at the caliph's pleasure, Al Aghlab and his successors ruled independently until 909, presiding over a court that became a center for learning and culture.*

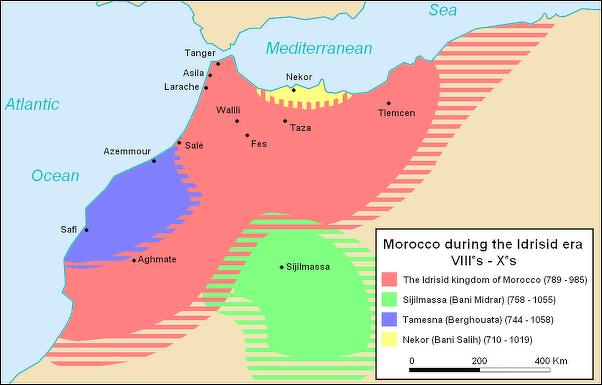

Idrisids

Just to the west of Aghlabid lands, Abd ar Rahman ibn Rustum ruled most of the central Maghrib from Tahirt, southwest of Algiers. The rulers of the Rustumid imamate, which lasted from 761 to 909, each an Ibadi Kharijite imam, were elected by leading citizens. The imams gained a reputation for honesty, piety, and justice. The court at Tahirt was noted for its support of scholarship in mathematics, astronomy, and astrology, as well as theology and law. The Rustumid imams, however, failed, by choice or by neglect, to organize a reliable standing army. This important factor, accompanied by the dynasty's eventual collapse into decadence, opened the way for Tahirt's demise under the assault of the Fatimids.*

Idrisids

One of the Kharijite communities, the Idrisids established a kingdom around Fez. It was led by Idriss I, the great grandson of Fatima, the daughter of Muhammad, and Ali, the nephew and son-in-law of Muhammad. He is believed to be have come from Baghdad with the mission of converting the Berber tribes.

The Idrisids were Morocco's first national dynasty. Idriss I began the tradition, which lasts to this day, of independent dynasties ruling Morocco and justifying the rule by claiming descent from Muhammad. According to a story in “Arabian Nights”, Idriss I was killed by a poisoned rose sent to hom by the Abbasid ruler Harun el Rashid.

Idriss II (792-828), the son of Idriss I, founded Fez in 808 as the Idrisid capital. He established the world’s oldest university, Qarawiyin University, in Fez. His tomb is one of the most sacred placed in Morocco.

When Idriss II died the kingdom was divided between his two sons. The kingdoms proved to be weak. They soon broke up, in A.D. 921, and fighting broke out between the Berber tribes. The fighting continued until the 11th century when there was a second Arab invasion and many North African cities were sacked and many tribes were forced to become nomads.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024